Everyday billions of singular events take place and the journalists should be able to report the most important ones. The selection of the occurrences that deserve a place in the media it’s not objective and depends on several, and sometimes subjective, factors, different people, views and organizational requirements.

Internally, each media makes its own choices about the events that are newsworthy, based on editorial criteria, on organizational restraints, on hierarchical decisions or even on the assumption of what pleases the audience, in a market-oriented choice. In spite of the different contexts in which the selection of news may occur, it is important to take into consideration the journalism theories about news values, which are defined by the set of criteria that an event possesses, which are capable of transforming it into news. In Wolf's words, the value of the newsworthiness of each event is defined by its aptitude for being transformed into news (Wolf, 2009). These criteria are related to the "news perspective", that is, they are acts of reading an event, that allow the media to decide what daily facts are most important to cover. We are, therefore, faced with a modus operandi of journalists, a knowledge rooted in their daily practices, which allows them to integrate a certain event in the normal and routine course of production.

Thus, as Wolf points out, we are before a set of elements through which the internal hierarchy of the media controls and manages the quantity and type of events that take place every day and, among them, choose the ones that are considered sufficiently interesting, significant and relevant to be transformed into news (Wolf, 2009). In fact, an event does not represent a single news value, but several news values combined. The more the news criteria define a certain event, better are its chances to appear on the pages of the newspaper.

Hall et al. (1978) address the values of newsworthiness in the selection of events that are transformed into news. In a generic perspective, the authors state that everything that goes beyond normality is likely to be reported. The uniqueness of the event would, thus, be the primary news value, and stands side by side with occurrences concerning elite people and elite nations, dramatic events, personalization of stories, and events with negative consequences. For Hall et al., disasters, dramas, the lives of the rich and powerful, along with perennial themes such as football, will always have space in the newspapers and this leads to journalists tending to highlight what is extraordinary, dramatic and tragic, in order to give even greater newsworthiness to the event. Another consequence is that events that contain one or more of these values will have more potential as news, than those that do not fit into any of them.

Several authors have made an inventory of different news values, so there is no single systematized theory. These criteria have evolved over the years, but there are some baseline news values that have been maintained over the years, such as the extraordinary, the unusual, the present, the prominence of the characters, the illegal, the wars, the calamity and death (Traquina, 2002).

Later, Gans (1979) work showed that most news featured prominent figures in society. The author distinguishes Knowns from Unknowns and concludes that most of the news actors are well-known people, at a rate of 76% of news reports and 71% of television news. The author further clarifies who these Knowns are, concluding that, mostly, they emerge from the political sphere. With regard to the Unknowns, they obtain about a fifth of the available time or space and, mostly, they are protesters and victims.

As for Galtung and Ruge (1965), who are among the forerunners in the study of news values, the criteria listed by the authors included the reference to elite people and negativity. Concerning the prominence of the people involved in the news, the authors consider that the actions of the elite are seen as more important than the activities of other members of society. Moreover, for Galtung and Ruge these elites serve as objects of general identification of ordinary men, not only because of their importance, but because the media system itself is organized in such a way as to give them antenna time, which is harder to happen for ordinary people.

As for negativity, the authors explain this news value based on several factors. First and foremost, because negative news satisfies the criteria of frequency better, that is, negative facts have more facilities to be reported and take less time to happen. The authors give examples of how long it takes a person to die in an accident, comparing to the time that leads to the socialization of the human being, and conclude by stating that a negative event is easier to unfold in two or more editions of the newspaper. Secondly, negative news are more consensual and unambiguous, since they allow a consensus around its interpretation as negative. Thirdly, we find the consonance of this type of news with what the authors call the pre-dominant images of our time. Galtung and Ruge explain this idea based on the population’s latent, or even manifested, need for negative news. Fourth, the authors consider that negative news are the most unexpected, in the sense that they are rarer and, therefore, less predictable (Galtung and Ruge 1965).

Galtung and Ruge did not only listed the news values, but also made it clear that these criteria are combined, and that the newsworthiness of the event is all the greater, the more news values it brings together. In this sense, the authors combine some criteria that translate into greater newsworthiness and, one of these combinations, is precisely the negative news about the elite people.

Regarding news values, Nélson Traquina (2002) emphasizes death as a fundamental news-value and stands that all people may head the news someday, as everyone faces the imminence of his death. The main difference is that these news may be highlighted (in the case of prominent figures or deaths in disasters) or only reported in the interior pages of the newspaper (the obituary). Notoriety is another criterion of newsworthiness, from the substantive point of view, according to Traquina’s theory. The author states that the celebrity, or the hierarchical importance of the individuals involved in the event, has value as news (Traquina 2002).

Harcup and O'Neill (2001) proposed ten requirements (power elite, celebrity, entertainment, surprise, bad news, good news, magnitude, relevance, follow up and newspaper agenda), considering that one news item should satisfy at least one of these criteria. The authors carried out a study in 2014 looking for a ranking of the most frequent news values in ten newspapers in the United Kingdom and concluded that 442 of the 711 analyzed news articles have a negative side (Harcup and O’Neill, 2017). The same analysis showed that references to power elites appear in 5th place as newsworthy events.

Negativity and power elites appear as two significant news value, which means that, when combined, they represent a strong event, in terms of its newsworthiness. Mota (2017) argues that the coverage of the death of public figures has suffered an increase in the volume of information material produced in the last 40 years, which is all the greater the higher the notoriety of personality.

The death of public figures has a significant news value and the discourse held by the media allows the public to participate in a ritual of grief (Lima, 2017). The study regarding the changes in the media, that considered the death of 20 Portuguese public figures, who died between 1970 and 2014, showed that the position of the personality in the public sphere is a guarantee of a more extensive media treatment (Mota, 2017). The same analysis presented signs of a ‘mourning journalism’, in the coverage of some of these deaths, concluding that this is a moment of exception, somewhat following the idea of critical suspension mentioned by Dayan and Katz (2005).

Covering the Death of a Political Leader: António de Oliveira Salazar

Combining negativity and notoriety as two of the most important news values, one can argue that an event like the death of the elite people is necessarily going to reach several media space. Death is disruptive and the mass media take advantage of this interregnum moment to foster biographical and dramatization narratives and to play the role of mediators of a certain collective mourning that affects the public.

As part of a broader study (Mota, 2017), the death of António de Oliveira Salazar, leader of the dictatorial regime Estado Novo, in Portugal, was analyzed in two newspapers, Diário de Notícias and Jornal de Notícias, and the conclusions showed that the main difference lies in the extent of the coverage, since the percentage of pages in which the event is mentioned in Jornal de Notícias is less than half of Diário de Notícias. The object of the present article is to enlarge the corpus of analysis and include other newspapers published in 1970, in order to understand the kind of coverage and the way grief was expressed by the periodicals, during the four days after the death of Salazar.

Lima (2017) already analyzed the wide coverage of this event in the Portuguese press, namely in Diário de Notícias, O Comércio do Porto, O Primeiro de Janeiro, O Século and Jornal de Notícias. Her analysis covered the period before the death and the four days after Salazar died, and the author found similar strategies in the five newspapers, but also differences in the number of articles, days and publications concerning the death of the dictator.

A similar study, held by Fernandes (2013), concentrated in the visual elements of the funeral of António de Oliveira Salazar, considering 41 publications. The conclusions showed that the ceremonials were covered using strategies to reproduce the reality ‘staged’ in his forty years of government, representing Salazar as a villager who became an university teacher, mourned in the Jerónimos Monastery, in a casket wrapped with the national flag, but buried in a shallow grave, in the village of Santa Comba Dão, where he was born.

Aiming to enlarge the study, we decided to analyze the coverage of Salazar’s death in the Portuguese press, considering the Portuguese daily newspapers Diário da Manhã, Diário de Lisboa, Diário de Notícias, Jornal de Notícias, O Comércio do Porto and O Século. This study included the four editions of each newspaper, following the date of death of the ex-President, 27th July 19701. The extent of the coverage (28th until 31th July 1970) was decided, in order to evaluate the coverage during the funerals, aiming to understand the forms of grief in the newspapers.

As for the newsworthiness of the event, aside from the combination between death and reference to elite people, we will try to understand if the coverage of Salazar’s death, despite the bias of the censorship, could emphasize or contradict other news values.

We will be analyzing newspaper editions dating from 1970 and reporting the death of the former President of the Council. Thus, it is necessary to take into account that the newspapers were published in a prior censorship scenario and they were reporting the death of the former leader of Estado Novo. In 1970 the censorship was called ‘Previous Exam’ and all the newspapers should submit their texts to the censorship office, prior to the publication. The office work was not limited to cutting texts, often giving the newspapers advice on what they should write and how they should write (Príncipe, 1970). At the same time, the journalists would often self-censor themselves (Forte, 2000; Azevedo, 1999).

Despite this control and the restrictions to the freedom of press, each media had its circumstances and a certain orientation, that sometimes made the difference. As García, Alves and Leonard sustain, some newspapers fought the regime, in a more or less declared way, and we should draw attention to the media as political actors, rather than as a merely passive or instrumentalized forces by the regime (García, Alves and Leonard, 2016). In that sense, we will regard the conditioning, the recreation of the ideology, but also the attempts of resistance. So, this article aims to compare the coverage of the death of António de Oliveira Salazar, in order to understand how the press dealt with the mourning in a dictatorial context.

António de Oliveira Salazar first came to the Portuguese government in 1928, as the Minister of Finance, after the coup d'état of May 28, that implemented a dictatorial regime. His political ambition allowed him to strengthen powers as Minister of Finance and, following a political crisis that led to the resignation of the prime minister, Salazar adds to the portfolio of finances, the colonies. On June 28, 1932, Domingos de Oliveira, president of the ministry, resigned and Salazar was called to form a government (Meneses, 2010).

In assuming the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, on July 5, 1932, Salazar headed the Estado Novo, an apolitical regime, concerned with its own survival, confused with the national interest, and with the preservation of order and obedience. The 1933 Constitution marked the definite transition from a military dictatorship to the Estado Novo regime.

Salazar was the leader of the Estado Novo dictatorship until 1968. In these 35 years of government leadership, he reaffirmed the nationalist vein that characterized the regime, maintaining a need to underline the greatness of the country and its achievements.

On August 3, 1968, Salazar fell from a chair, an episode that would add to an increasingly weak health situation. Faced with the deterioration of his state of health, it was necessary to appoint a new President of the Council, which happened on September 28, 1968, when Marcello Caetano replaced António de Oliveira Salazar. In the last two years of his life, Salazar believed that he was still the President of the Council, in a state of semi-lucidity, and made possible by the fact that he stayed in the official residence of the government, continued to receive ministers and to discuss politics, without having access to the mass media (Nogueira, 1985).

Salazar died on July 27, 1970 and the funeral took place on July 28, from São Bento to the Jerónimos Monastery, where the funerals were held the next day. He was buried in his hometown, Santa Comba Dão, and the corpse was carried by train.

The day after Salazar died

The day after Salazar’s death, 28 july 1970, all the newspapers highlighted the event in their front pages (Figure 1) and Diário da Manhã, Diário de Notícias, O Comércio do Porto and O Século dedicated their entire front pages to the death of Salazar. This editorial option assumes major importance, since, in the 70’s, the front page of the newspapers could contain more than a dozen subjects. On this same day, only Diário de Lisboa and Jornal de Notícias inserted other subjects in their front pages.

Regarding the images chosen to the front pages, in Diário de Notícias and O Século we find an active Salazar, in full exercise of his functions as President of the Council. O Comércio do Porto, Diário da Manhã, Diário de Lisboa and Jornal de Notícias seemed to want to remind the former Head of State at a point of his life when he was most weakened. We should also point out that Diário de Notícias, O Comércio do Porto and O Século chose to put an image of Salazar dead, lying in bed.

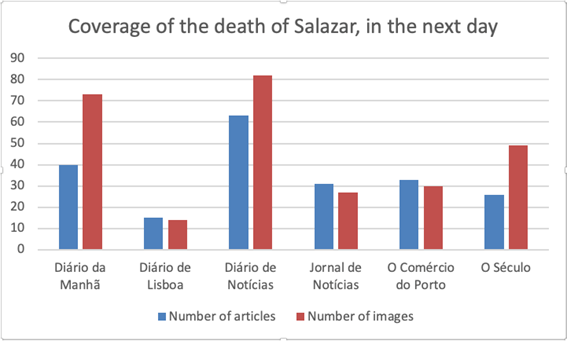

Each newspaper dedicated about half of their editions to the occurrence (Graphic 1). Diário de Lisboa has the lowest rate of coverage (21.8%) and Diário da Manhã is the newspaper with the higher coverage rate (87.5%). Diário de Notícias (50%), O Século (50%) and O Comércio do Porto (44%) are closer to Diário da Manhã. Jornal de Notícias covered the event in 31% of its pages, an editorial option more similar to Diário de Lisboa.

The pieces of news are mainly biographical and focus on Salazar's actions as head of the government. The newspapers made a true effort to reconstruct Salazar’s life and actions, with long texts, since his school days until his death.

The newspapers also gave a detailed account of the statesman's last hours and the circumstances of his death. In Diário de Notícias, the journalist summarized, minute to minute, the moments after the death of Salazar: ‘At 10:42 the prof. Marcello Caetano, in black tie, arrived at the residence of St. Benedict. Eighteen minutes later, the President of the Council would go to his office’ (Diário de Notícias, July 31, 1970). O Comércio do Porto published an article that lists all the personalities who visited the corpse and divulged details as the origin of the first flowers that arrived at the residence.

Still in the scope of the information content, the newspapers emphasized the messages of condolences and the reactions to the death of Salazar, in Portugal and abroad, highlighting what the major foreign newspapers said about Salazar, detailing the tributes that would take place in the former colonies and across the country and summarizing the messages of condolences received from all over the world. In addition, the pieces of news anticipated, in detail, the exequies of the next days.

There seems to be an attempt to show Salazar's relevance, especially at an international level, by exposing the feelings of grief expressed by people and institutions. The fact, for example, that every newspaper wrote about the mood of sadness in the Portuguese colonies, can be seen as a way of legitimizing government action in those regions. At a time when several voices were asking for the decolonization, the way that the newspapers reflected the grief in these territories, may be seen as a way of showing that those people cared about the ex-President and, implicitly, agreed with the colonization.

The funerals

From July 29 to July 31, 1970, the newspapers reported the funerals of António de Oliveira Salazar, held first in Mosteiro dos Jerónimos, Lisbon, and heading to Santa Comba Dão, the place where Salazar was born and where he was buried. The corpse was taken by train, in a procession escorted by thousands of people

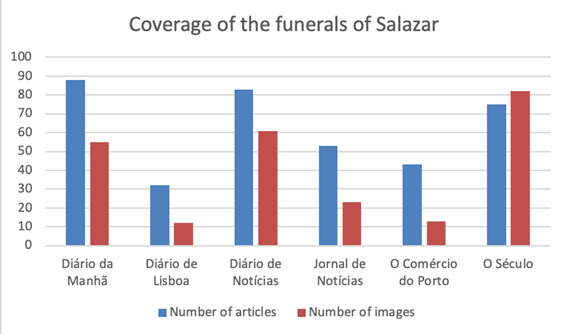

Taking into consideration the three days of the funerals, we can see the major differences in the coverage (Graphic 2). Diário da Manhã occupied the larger percentage of pages with the events (76.9%), followed by O Século (33.8%) and Diário de Notícias (27%). O Comércio do Porto and Jornal de Notícias occupied between 15 and 18 percent of its pages with the coverage of the funerals, but the number of articles was substantial. Diário de Lisboa had the less coverage rate, with 14.2 percent of its editions dedicated to the funerals of Salazar and less articles written about it. Comparing the approaches, we found a significant difference in the breadth of the coverage, that was much wider in Diário da Manhã (88 articles and 55 images) and narrower in Diário de Lisboa (32 articles and 12 images).

Despite the differences, all the newspapers produced pieces of news describing the atmosphere of the funerals and made a comprehensive list of the people who attended the ceremonies. The journalists accompanied both the procession between São Bento and the Jerónimos Monastery, and the trip to Santa Comba Dão, where Salazar was buried.

The images

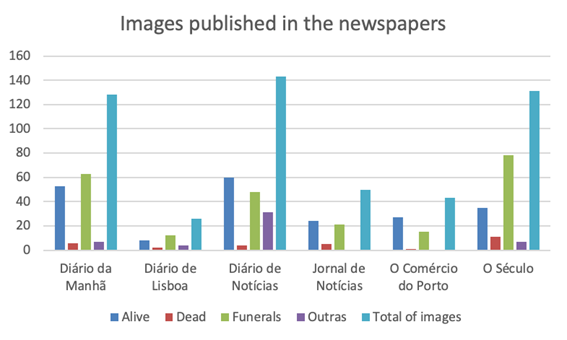

In all of the newspapers, the visual elements assumed great importance, with the publication of photo-captions or smaller photographs next to the chronologies, an option that shows the importance given to the visual content, at a time when the graphic options faced difficulties in the newspaper composition process. In fact, the six newspapers published 521 photographs during the four days after the death of Salazar (Graphic 3).

Diário da Manhã, Diário de Notícias and O Século published more than 100 images each, mainly illustrating the funerals and the tributes that took place, but they also printed pictures of the public life of Salazar, supporting the biographical articles. Diário de Lisboa, on the other hand, summed 26 images in its four editions and it should be noted that the newspaper only represented Salazar alive in the day that he died, since in the next three days the newspaper published two images of the dead body and 10 images of the funerals. As for Jornal de Notícias and O Comércio do Porto, each one published about 50 images, mainly representing Salazar alive and illustrating the funerals.

All of the newspapers published at least one image of Salazar dead in his bed or inside the coffin. Some of these are panoramic images, where we can identify the body inside the coffin, but it is not possible to take a clear look at it. Instead, other images allow the public to look at the corpse very clearly.

In the early 1970s there seemed to be no ethical constraints in publishing images of the corpse of a public and political figure like Salazar. The funeral ceremonies were opened and extended (three days passed between the death and the funeral), so the newspapers chose to show images of the corpse of the former President of the Council. This attitude of showing the dead body is not consistent with the most restrained posture in the current newspapers, as some authors defend (Hanusch, 2010; Zelizer, 2010), but it can be justified by the fact that it is a nationally prominent personality who has ruled the Government for 40 years.

Discourse subjectivity

Before exploring the subjectivity in the newspapers discourse, we should take into account the strong ideological load that affected the publications in this period of time. In addition, we should remember that the writing style of the early 1970s was substantially different from the journalistic rules that are now accepted, since the apologetic tone and the use of laudatory adjectives was characteristic of the news written by the journalists, in particular the ones working in the media committed with the political regime. The norms of the censorship dictated that the journalists could not report any texts that could “hurt” Salazar, stating that his “work as a man and as a politician, can only be discussed in terms that do not diminish his image” (Azevedo, 1999). As an example, a telegram dating July 1970, establishes that the newspapers could not publish images of Salazar’s housekeeper, kissing his dead body and that, when describing the train journey to Santa Comba Dão, the journalists should not explain that the amount of people in the Coimbra station was due to the closure of the stores that day (Príncipe, 1970).

The form of treatment regarding Salazar is common to every newspaper analyzed, since in the vast majority of the texts, the name Salazar is preceded with a title. The most common form of treatment is ‘President Salazar’, which is significant, because not only the word ‘president’ is capitalized (something that emerges from the writing style of the newspapers), but also it attributes a position to the personality that he no longer holds. Another way of referring to the subject is ‘dr. António de Oliveira Salazar’ or ‘prof. Oliveira Salazar’.

Still, in Jornal de Notícias and Diário de Lisboa it was possible to find some titles and even some texts in which the word ‘Salazar’ is written without any prefixes. Diário de Lisboa uses a more respectful form of treatment in the edition dating from the day Salazar died, but in the next three days the most common form of treatment is just ‘Salazar’ and sometimes the newspaper underlines that the he was no longer the President, naming Salazar as ‘the former President of the Council’ or ‘former head of government’.

Besides referring to him as President or dr. Salazar, Diário de Lisboa has no other signals of subjectivity in its articles and sometimes we can read a non-apologetical tone, for example, when the journalist states that Américo Thomaz was reelected President after an indirect suffrage, or when he refers to the people looking at Salazar’s face, since ‘few were the occasions in which Salazar appeared in public’ (Diário de Lisboa, July 9, 1970). In most of its texts, Diário de Lisboa merely describes the facts, and when writing Salazar’s biography, the journalist does not form any judgment, but instead explains the facts with quotes from official speeches given by Salazar.

The subjectivity is also less prominent in the news published by Jornal de Notícias, but we can still identify examples of adjectives like ‘ilustrious deceased’ or ‘fair and magnanimous’ (Jornal de Notícias, July 31, 1970).

Concomitantly, in O Comércio do Porto, we also detected less subjectivity in the pieces of news, and, in some occasions, we found signals that can be interpreted as attempts to escape the apologetic discourse that the censorship expected: ‘prof. dr. Oliveira Salazar took the measures that the circumstances imposed on the defense of our rights and national sovereignty - measures that, for being recent, do not need to be recalled in this biographical sketch, because they are still very fresh in the memory of all the Portuguese’ (O Comércio do Porto, July 28, 1970).

On the contrary, O Século, Diário da Manhã and Diário de Notícias congregate the main examples of subjectivity. O Século published a five pages article with the extended biography of Salazar, in which is clear an apologetic tone, justifying some of the most controversial measures of Estado Novo (such as the Colonial War) and highlighting the unselfishness of Salazar. Concerning the non-participation of Portugal in the First World War, the journalist writes that it was due to ‘the effort and sacrifice of prof. Salazar, who at all costs wanted to maintain - and maintained - Portuguese neutrality’ (O Século, July 28, 1970). Another example settles the relevance of Salazar’s action in the Portuguese colonies, referring to the ‘greatness with which we gladly reoccupied and re-established the national sovereignty in that distant Portuguese territory’ (O Século, July 28, 1970). The article also highlights the importance of Salazar in the combat of communism and considers that ‘the Nation owes him a high precept for the noble character he has always revealed and for the services that he has not only provided to the Country but to the defense and prestige of the Western Civilization’ (O Século, July 28, 1970).

Diário de Notícias also legitimates Salazar’s actions, affirming that ‘like all great men, it was at the hour of greatest danger to the Fatherland that Salazar revealed himself in the fullness of his character, his courage and his confidence’ (Diário de Notícias, July 28, 1970).

As for Diário da Manhã, the newspaper publishes a 14 pages biographical article, describing the public life of Salazar, and entitled ‘The man that was Portugal for 40 years’. Diário da Manhã also justifies Salazar’s actions, highlighting “the wise helmsman in the sea of recent times” and stating that time “will take care to raise very high this Man, that Portuguese figure who saved Portugal from the abyss, this uncontested authority of the Lusí Spirit” (Diário da Manhã, July 28, 1970).

It is very clear the effort to present Salazar as a simple and humble man. In the editions of O Século we found numerous examples of this kind of discourse, describing, for example, the pieces of furniture in Salazar’s bedroom, made of mahogany and not wood, and without any pieces of decoration. The simplicity of the funerals has been exalted several times, side by side with the reminder of the fact that Salazar was a man of the people: ‘In life as in death, he wanted to be (…) just people, this people he was deeply involved with and always wanted to keep in touch with’ (O Século, July 28, 1970).

The use of adjectivation can also be found in the attribution of qualities to António de Oliveira Salazar, especially in Diário de Notícias, O Século and Diário da Manhã. The newspapers describe Salazar as ‘one of the greatest Portuguese of all times’, underlining that ‘Salazar was the Chief, he was the Outstanding Guide, he was the Builder of a Country’ (Diário de Notícias, July 28, 1970). The apologetic discourses can also be found in sentences like: ‘someone who, on its own merit, has the right to occupy one of the top places in the gallery of the great national spirits’ (Diário de Notícias, July 29, 1970). The texts also refer to Salazar as a ‘reflected spirit’, possessing ‘independence, elevation, lucidity and common sense’ (Diário de Notícias, July 28, 1970).

Exploring the differences

The differences of coverage rates and discourse subjectivity among newspapers could be explained considering the different administrations that, at the time, headed each one of the publications and on the dissimilar editorial positions. In fact, not only the censorship apparatus imposed the previous exam of the newspapers pages, but also, in the newspapers connected to the regime, as Diário de Notícias, Diário da Manhã and O Século, the journalists had to respond to another type of censorship: the one imposed by the direction of the newspaper (Azevedo, 1999).

Jornal de Notícias was aligned with the regime until 1945, but after the Allies victory in the Second World War, as the public opinion grew into the movement to the return of the democracy, Jornal de Notícias (owned by Manuel Pacheco de Miranda since 1943) became an opposition newspaper (Forte, 2000). As for Diário de Lisboa, it was not committed with political and economic power, and its democratic orientation was opposed to the political regime. In fact, its director was Norberto Lopes, a convicted member of the opposition, and the newspaper was mainly read by the intellectual bourgeoisie contrary to the political regime (Correia and Baptista, 2007). O Comércio do Porto, despite its identification with the political regime, was characterized by a distancing towards the government, since they prioritized the objectivity (Correia and Baptista, 2007).

On the other hand, Diário de Notícias was the regime’s unofficial newspaper, not only because its director in 1970, Augusto de Castro, had been a member of the Estado Novo regime and minister of Portugal in Brussels2, but also because Diário de Notícias was one of the most widely read Portuguese newspapers and the one which most faithfully reflected the governmental orientations (Correia and Baptista, 2007). Diário da Manhã was also a markedly pro-government newspaper, since it was owned by the National Union, the political organization created to support the Government of the Estado Novo and its director, Barradas de Oliveira, was close to the regime (Correia and Baptista, 2007). In the case of O Século, it was owned by an economic group (Banco Intercontinental Português) and openly supported the dictatorship. Despite that fact, the newsroom of O Século had several members opposed to the political regime, but under the circumstances, it had a favorable position towards the government (Correia and Baptista, 2007).

The newsworthiness of the event

Considering its newsworthiness, the death of Salazar was an event that fulfilled many of the news values listed by the different authors. As we have seen before, death/negativity and notoriety/reference to elite people are the more prominent news values in this case and the combination between them helps to explain the attention that the occurrence received from the media.

The death of Salazar gathers other news values, such as amplitude (Galtung and Ruge, 1965; Traquina, 2002) and magnitude (Harcup and O’Neill, 2017). The event assumed major importance for all the newspapers and was the main theme during the exequies, despite the fact that it was treated with greater importance by some newspapers. As for being meaningful (Galtung and Ruge, 1965) or relevant (Harcup and O’Neill, 2017; Traquina, 2002), the event fulfilled these news value entirely, in terms of its cultural proximity and in terms of its impact on the nation.

On the other hand, in terms of continuity (Galtung and Ruge, 1965) or follow-ups (Harcup and O’Neill, 2017), the newspapers that were closer to the government payed more attention to the event, unlike the publications connoted with the opposition. The study held by Mota (2017) shows that Diário de Notícias referred to Salazar every day in the eleven days following his death and Jornal de Notícias disregarded his death three days after the funeral.

Actually, regarding the frequency (Galtung and Ruge, 1965) of the event, the death of Salazar, despite being held during a longer time span, was covered by the Diário de Notícias, Diário da Manhã and O Século until and after its climax (the burial), with many details, such as the people present, the coverage of international media or the mourning signals across the country. This is an exception to the frequency news value, according to which “the more similar the frequency of the event is to the frequency of the news medium, the more probable that it will be recorded as news by that news medium”. All the daily newspapers, despite the coverage differences, accompanied, day by day, what followed the death of Salazar.

Salazar’s death was expected by the newspapers, since Salazar was sick for a long time. So, his death was consonant (Galtng and Ruge, 1965; Traquina, 2002) with the media expectations and we believe that not only the newspapers were expecting the death of Salazar, but also some material was previously prepared for publication, such as imagens and biographical texts. This can also be read as a signal that the newspapers had previously prepared the kind of apologetical tone found in Diário de Notícias, Diário da Manhã and O Século. The journalist Lumena Raposo3 admitted that Salazar’s death was expected, since Diário de Notícias, one hour after the announcement of his death, printed a special edition. We can argue that the subjectivity was not built in the moment, nor influenced by the emotions: it was carefully prepared, since the newspapers knew that Salazar was going to die anytime soon.

Conclusion

The death of António de Oliveira Salazar had a great prominence in terms of the percentage of space occupied in the analyzed newspapers and also in terms of the media discourse, especially in Diário da Manhã, Diário de Notícias and O Século. These three newspapers were closer to the regime, so they paid more attention to the death of the former President. On the other hand, Diário de Lisboa, O Comércio do Porto and Jornal de Notícias were less uncommitted, politically speaking, which could help to understand the fact that they used less space to cover the death of Salazar.

Our conclusions are in line with Lima’s study (2017), in which the author found that the newspapers based in Oporto (Jornal de Notícias and Comércio do Porto) adopted a restrained attitude and the complimentary tone of the discourse was found under quotes. According to the same analysis the newspapers based in Lisbon used a more laudatory language and dedicated more attention to the event, using many adjectives and figures of speech. Still, we believe that the breadth of the coverage of Salazar’s death is conditioned by the editorial orientation of each newspaper.

Besides that ideological orientation, the fact was that the newspapers were covering the death of António de Oliveira Salazar, and it is obvious that the discourse was dictated by the fact that it referred to the death of the President of the Council, at a time when Estado Novo was still in force and the censorship was mandatory. The expressed grief and the apologetical tone aimed to reinforce the actions of Salazar, to justify some of his political decisions and to show that the impact of his death was transversal to the Portuguese society, to the leaders of foreign countries and even to the colonies.

As for its newsworthiness, not only the event gathers a considerable number of news values (death, proximity, notoriety, amplitude), but it also overtakes other points, such as the frequency. The death of Salazar was consonant with expectations, and the fact of being an expected death underlines the subjectivity used by the newspapers.

One can argue that the fact that Salazar died during the Estado Novo, and because some of the newspapers were closer to this regime, is a sign of bias in the results. In this context, one could even ask the pertinence of this case study. We should point out, as previous studies showed (Mota, 2017), that the recognition of public figures by the media does not depend on a determination of the public authorities, even when they may resort to forms of imposition such as censorship. In fact, the process of mediatization of public figures obeys to more complex forms of construction of a public narrative that, in spite of not being unrelated to institutional discourse, also depends on its conformation with the languages and ideologies of the media, in articulation with public opinion, of which the media are, in part, product and producers. In fact, the six newspapers were being submitted to censorship and were published under a restrictive regime concerning freedom of press, but, still, Diário de Lisboa distanced itself from the more committed approach of O Século.

Considering these different approaches, and in relation with the fact that Salazar’s death was expected, we can conclude that the journalists had time to write and rewrite, for example, the biographical pieces. The different tones were chosen, and we’re not triggered by the moment. The more independent newspapers managed to mourn Salazar and still maintained their identity, despite the imposed norms of the censorship. The other publications reinforced their closeness with the political regime and grieved the death of the former President, utilizing the opportunity to legitimize Salazar’s actions and to demonstrate that his loss was felt by the entire country and all over the world.