Introduction

Social media platforms, not only allow the users to get in touch with the others individually, but also helps them to form online groups. With its features such as groups and pages, especially Facebook, allows the users to the get together online. These groups and pages could turn into online imagined communities comprised of the users with similar interests. The diasporic groups, the main target population of this study, tend to get together on social media platforms as well. Their diasporic identities become their key and common feature to gather online, which enables them to create online imagined communities.

The concept of imagined community initially referred to the formation of nations and nationhood, however the subsequent debates situated this concept into other various formations as well, such as religious, transnational, and diasporic imagined communities. These formations have similar key features with Anderson’s theory but differ in terms of certain components such as the people within these communities or the underlying ideologies. Anderson asserted that all communities that had no face-to-face contact were imagined (Anderson, 2006, p.6), however today with the advent of internet, the members of an imagined community have better chance to virtually get in contact with the other members. In this regards, the social network platforms like Facebook, provide an opportunity to form new online imagined communities (Parks, 2011, p.106).

Facebook brings people and the members of the same imagined communities together on a digital platform and reforms the imagined communities on online basis. Facebook pages gain importance for this study, because they are hybrid formations between the personal profiles and Facebook groups (Ayu, Abrizah, 2011, p.240). This study argues that, certain Facebook pages situate their members into particular online imagined communities that are predetermined by the admin(s). This formation especially helps the diaspora to contact with other members of this community as well as the people in their homeland. To the best of our research, Facebook pages and groups are highly popular among the Turkish diaspora in Germany. They use Facebook to manage strong links with other Turks in Germany as well as to maintain their ties with Turkey. The role of Facebook creating online imagined communities for diaspora have not been studied frequently and most researches focused on how the diaspora use Facebook to connect with each other (Marcheva, 2011; Al-Rawi, 2017; NurMuhammad et. al, 2015). These studies analyzed the diaspora’s usage of social media and their diasporic identities however they did not focus on Facebook’s role as a digital tool. Although these studies contribute greatly to our understanding of online imagined communities, there is a need for understanding the role of Facebook, as a medium to form new online imagined communities.

The purpose of this study is to answer the fallowing research question: “What is the role of Facebook in creating a diasporic imagined community for the Turkish-Germans?”. We will examine a specific Facebook page for the Turkish-Germans, called “Almanyadaki Türkler” (Turks in Germany) and analyze the posts that were shared on this page between January 1 and December 31, 2018. Within the conceptual framework of the imagined community, we will textually analyze the diasporic posts on the page and reveal the main components along with the elements of those posts. Furthermore, we will analyze the elements that were most frequently used in the posts in order to create an online diasporic imagined community. This study is important in terms of understanding the role of Facebook and its connection with the imagined community concept as well as questioning if these formations also create an online imagined community.

Imagined communities and their consolidation elements

According to Anderson, nation as an imagined political community is imagined, because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow members and meet them or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each of them, the image of their communion exists (1991, p.6). Despite the fact that the imagined community concept referred to a nation and its role in identity construction, indeed it described the formation of many other groups (Ay, 2017, p.935). In this sense, religion, place, gender, politics, civilization and science have all been specified as bases for the formation of imagined communities (Phillips, 2002, p.600). In a similar manner, Calhoun defines the imagined communities as the large collectives, whose members are linked primarily by common identities but minimally by networks of directly interpersonal relationship such as nations, races, classes, gender, Republicans, Muslims, and “civilized people” (1991, p.95-96).

As mentioned above, nation is not the only form of imagined community. Other forms of social closure, such as the religious community can be considered as precursor of nation (Bilici, 2006, p.316). Basically, the ummah is the community of Muslim believers. It is exposure to a single narrative through sacred texts and images that renders otherwise unrelated individuals a community (Bilici, 2006, p.319). There are certain elements and components for the communities to be constructed and imagined by the people who belong to them. Anderson argues that by creating a common field of communication, language serves as a key foundation for creating a national consciousness in the process of a nation’s rebirth, creating a sense of belonging (1991, p.285). Therefore, he designates the language as one of the origins of national consciousness (First, Sheffi, 2015, p.342); because, it is a tool for people to bond with each other and therefore, it is difficult to form the imagined community with the people who cannot understand each other (Been, Arora, Hildebrandt, 2015, p.9). Sacred text and language are important components for the religious imagined community as well (Bilici, 2006, p.316).

Apart from the language; flags, symbols, territory and social historical mythology are also considered as the important components of an imagined community (Avraham, Daugherty, 2012, p.1386). The imagined community makes use of symbols, of which the flag, an ancient symbol but associated with the concept of nationalism in modern times, is the most profound; because it is flown at every cultural, economic, or political event, it appears on the television screen at the end of daily broadcasts on state-run television, it flies over government buildings and over private homes on national holidays, and it is carried by activists on formal occasions (Avraham, First, 2003, p.287). On the other hand, the political leaders, anthems, the land and its borders, territory, a common history, collective memory and common values are also important aspects to form an imagined community (Avraham, First, 2003, p.286; Kijonka, 2017, p.235; Anat, First, 2007, p.286).

A nation as an imagined collectivity is too big to be grasped by individuals; thus, a sense of belonging and the we-feeling are important for the formation of an imagined community (First, 2015, p.240). The sense of belonging and we-feeling are stiffened through the shared experiences, activities, and places (Amit, 2002) because the social interaction creates and maintains the imagined community (Dagson, 2017, p.23). However, an imagined community is not just about the national boundaries, it is also about the people who imagine it. People in diaspora are also a part of their national imagined community, because its scale and range are not limited to its native region.

Turkish-Germans and the diasporic imagined community

The Turkish diasporic community is one of the largest national groups in Europe with over six million people.1 The majority of Turkish diaspora in Europe resides in Germany, constituting a population of approximately three million people.2 They are members of an imagined community because they are aware of their local cultural sovereignty and their native culture, language and traditions differ from the local citizens (Kijonka, 2017, p.243-244). They are not only the member of the Turkish nationalistic imagined community, but also, they form a diasporic imagined community.

The singular imagined community of the nation is achieved to some extend by the projection of foreign imagined communities, the construction of the social unity of the majority arising from the formulation of the alterity of minorities who do not fit into the national narrative (Thobani, 2011, p.536). In this case, the Turkish diaspora in Germany, as the minority, constructed an imagined community for themselves. The population retains a rather strong identity awareness, which is linked to the memory of its territory and the society of origin, in its history that implies the existence of a strong sense of community and community life, which can be considered as the formation of a diasporic imagined community (Bruneau, 2010, p.36). Diasporic identities are imagined, and diasporas constitute the imagined communities in which the sense of belonging is socially constructed on the basis of an imagined and symbolic common origin and mythic past (Gorp, Smets, 2015, p.72). As Guibernau states, a common culture favors the creation of solidarity bonds among the members of a given community and allows them to imagine the community they belong to as separate and distinct from others. Solidarity is then based upon the consciousness of forming a group, outsiders being considered as strangers and potential enemies and the individuals who enter a culture, emotionally charge certain symbols, values, beliefs and customs by internalizing them and conceiving them as part of themselves, (2007, p.82) as well as the collective memory and the common historical events (Bruneau, 2010, p.40).

Emigrant groups have been conceptualized as diasporas and the diaspora designates collectivity (Brubaker, 2005, p.4). In this regard, diaspora organizations play an important role for constructing the imagined communities. They represent the ability to transform largely virtual imagined communities into more tangible communities of practice, as they gather participants around the shared activities such as celebrations, commemorations, festivals, manifestations or shared places such as community centers. In this regard, the collective process of diaspora involves recognition of a common emotional and cultural attachment to an imagined community that exists beyond the state borders. Diaspora organizations aim to foster belonging through the events they organize and are mainly concerned with forming imagined communities as cultural mediators (Gorp, Smets, 2015, p.73-80). At this point, collective action should be underlined, because nations and other social formations are imagined through the representations of collective action (Calhoun, 2002, p.156) The construction of cultural belongings is inherent to the formation of diasporas and the groups that are classified as immigrant groups in their country of residence can redefine themselves by taking on the label of diaspora, consequently, they can position themselves as members of a larger transnational community that exists beyond the borders. Sense of belonging encompasses different time-space dimensions, related to past, present and future understandings of the imagined communities and their ties of belonging (Gorp, Smets, 2015, p.78-81).

Language usage plays a vital role for the diaspora in constructing a diasporic imagined community. Majority of the Turkish diaspora in Germany are bilingual and use both languages in their daily life (Yılmaz, 2014, p.1650). Especially the third generation developed a new hybrid language which they call “Germanized Turkish”3 (Brendemoen, 1992, p.19). Being a concoction of Turkish and German, this language became a part of their identity. It became an important aspect of the diasporic imagined community as in the case with the importance of language to shape a nationalistic imagined community.

Competence in the language ensures them to communicate with the people in their homeland and allows them to share their religious, ethnic or national identity (Mills, 2005, p.261-266; Woldemariam, Lanza, 2015, p.174). In addition to these aspects, with the advent of internet, social media started to take an active role by serving as the intermediary platform for the diasporic identities to engage with their homeland. The diasporic groups started to come together on online platforms to connect with the fellow members of their diasporic and national imagined community.

Online imagined communities and social media

It is acknowledged that media has an important role in constructing the imagined communities (Ay, 2017, p.933). Internet can enable the ethnic communities to globally react, communicate, share resources and to mobilize in reaction to the global events (Srinivasan, 2006, p.503). Social media have managed to bring billions of people together from all over the world who get in touch online and communicate virtually with each other even if they have never met, in the same way that the members of an imagined community do, just as Anderson indicates (Kavoura, 2014, p.491). The number of people with network access increases each passing day and this promotes the creating of new imagined communities (Kavoura, Borges, 2016, p.256). The social network platforms such as Facebook are virtual nations that offers the community members an imagined sense of identity and belonging which they aspire to get (Al-Rawi, 2017). Facebook allows its users to create pages and groups that agglomerates numerous users under one “digital” roof which enables them to construct online imagined communities (Acquisti, Gross, 2006, p.38). It is an online community based on the social relationships rather than the geographical territories (Enli, Thumim, 2012, p.95).

According to Anderson, daily newspaper reading is a mass ceremony, in which each communicant is well aware that the ceremony he performs is being replicated simultaneously by thousands or millions of others of whose existence he is confident, yet of whose identity he has not the slightest notion. (Culler, 2003, p.33-35). As for the social media, this ceremony is maintained by the imagined audience, which is the mental conceptualization of the people with whom they are communicating (Litt, 2012, p.331). The imagined audience consists of all of the user’s followers who the user thinks he or she is communicating with and all other users that the shared posts may be visible to (Duong, Zeller, 2017). Constructing an online imagined community through social media also allows the users to virtually share their experiences and activities. Posting pictures or videos about the community activities, provides a visual experience for the other users, thus allows the members of that imagined community to engage in the activities at any time and from anywhere online (Cheong et. al., 2009, p.295).

Social media have functioned as the enabler for the globally dispersed people to contact with each other (Leurs, Ponzanesi, 2011), which especially served the purpose of creation the diasporic communities. Social media provided the ability for dispersed groups such as diasporas to connect, maintain, create, and recreate social ties and networks with both their homeland and their co-dispersed communities; thus, social media offers the possibility to sustain and recreate diasporas as globally imagined communities (Alonso, Oirzabal, 2010, p.9). It becomes an online imagined community, to which they can contribute with their life stories, photographs, and memories, creating a completely self-made and self-preserved space for themselves (Liberatori, 2018, p.641). These spaces could be created and used by the individuals or other imagined communities such as the nationalistic and/or religious ones. For instance, Mandaville states that, social media provides spaces where diasporic Muslims such as Turkish-Germans can go, in order to find others like them, by doing so, social media allow them to create a new form of ummah that is online ummah (1999, p.23). In this case, groupings within the social network sites gain importance. Facebook, allows its users to create groups and pages to gather the people together as members of those groups and pages. These users need to share the same interests for that specific group and have specific bonds that relate them (Kavoura, Stavrianea, 2015, p.517).

Members of the crowded groups or pages could never know every other member; however, they are certainly aware of other members’ presence just as in Anderson’s concept (Gruzd, et. al., 2011, p.1298). Groups and pages not only enable the user identification and solidarity but also create a shared space where the members can interact in all the ways that Facebook enables (Odumosu, Eglash, 2010, p.103). Facebook page followers constitute the online diasporic groups and the members of this groups hold a common identity due to their possible shared history, experience, language, culture, and religion (Alonso, Oiarzabal, 2010). These pages can express sentiments and opinions towards their host country or their original homelands. Facebook has become the online community’s virtual and imagined homeland, because it is the medium where the online community members scattered all around the world meet and interact with each other based on their shared language and experiences (Al-Rawi, 2017). Thus, the members of the diasporic community constitute a digital diaspora on the social media (Brinkerhoff, 2009, p.1-2). The members of an online Turkish-German community, come together online to exchange relevant information and news, and sometimes strengthen their link to their original homelands by reminding themselves of their possible common cultural heritage (Karim, 2007, p.371).

Methodology

The web has become a virtual diasporic space which opens up, to those who have left their country, a new means of confrontation and social participation in order to form a virtual map for their diasporas (Marcheva, 2011). For any diasporic community, Facebook serves as a place where they keep in contact with both their homeland and diaspora, identify with other groups with shared roots, feel proud of a common identity, and get informed about the other diasporas (Oirzabal, 2012, p.1478).

In this study, using textual analysis, we analyzed the discourse on a Facebook page in terms of the concept of imagined community. We opted to use the textual analysis, primarily because it focuses on the underlying ideological and cultural assumptions of the text which is understood in its broader, post-structural sense as any cultural practice or object that can be read (Fürsich, 2009, p.240-241). It enables us to understand the ways in which the members of various cultures and subcultures make sense of who they are and how they fit into the world in which they live (McKee, 2003, p.1). The subculture we will examine in this study is the Turkish-German diasporic culture and the main question is that how they create an online imagined community on a Facebook page.

Facebook groups are excluded in this paper; because in these groups, every member could share posts, which causes a large number of topics which may or may not relate to each other or the purpose of the group. However, on Facebook pages, which is the formation to be examined in this study, only the admin(s) is allowed to share posts; consequently, the followers’ interaction with the page is limited to liking the post, commenting beneath, and sharing it.

In this study, the Facebook page called “Almanyadaki Türkler”, and its one-year activity were analyzed. This is the largest page in its kind with 14.918 followers.4 As explained on the page’s “about” section, the main aim of the page is to gather the Turks living in Germany together. The followers see the contents chosen by the admin(s) on their home page, therefore, choosing the content also functions as predetermining the imagined community to which the followers are going to be the members. For instance, the selected page subsumes the followers mainly under three sorts of imagined communities; nationalistic, religious and diasporic.

In order to determine these three sorts, we examined the posts shared in the one-year period selected for the study. We examined the visual elements, spoken and written languages within the posts, and the explanations or captions of the posts. After carefully assessing, we opted for certain elements which existed in many posts. We determined the categories of imagined communities into which these elements would fall: nationalistic, religious, and diasporic. Then, we developed a codebook for the posts shared in the one-year period based on the selected Facebook page and coded it according to 27 factors: content, content type, format, length, music usage, post type, spoken language, written language, place in the representation, comments’ language, number of comments, number of likes, number of views, number of shares, type of imagined community, nationalistic speech/visual/text/symbol, religious speech/visual/text/symbol, diasporic speech/visual/text/symbol. It was found that of 158 posts, 116 contained the nationalistic elements, 66 contained the religious ones, and 33 contained the diasporic ones.

In line with the purposes of this study, we focused on 33 posts containing the diasporic elements.5 First, we analyzed the components of the posts such as the prominent subjects, the language usage, the source which the post been was from, and the place in the representation. Second, we analyzed the elements constituting the imagined communities according to the way they were used in the posts and shared on the selected page. Third, we linked the inferences drawn from the results of the first and second analysis. Through this methodological approach, we aimed to understand if and how a Facebook page constructs an online imagined community for the Turkish diaspora in Germany.

Findings

In accordance with the main subject of this study, only the posts containing the diasporic elements were examined. The prominent subjects in these posts were the marginalization against the Turks in Germany, collective solidarity and support. There were three languages spoken on the video contents, that is, German, Turkish, and Kurdish. However, German was the most commonly used language. Turkish and German were used in the written statements; however, in some posts there were bilingual statements. Nevertheless, Turkish was the most commonly used language in terms of the written posts. Regardless of the content type, almost in every post, the place in the representation was apparent. Among these posts, Turkey and Germany appeared to be the main locations.

There are certain elements to determine the category of imagined communities for each post. Some of these elements are exclusive to its category and some of them are common in every category. In the 33 posts examined; land, military, national slogan, ethnicity, political leader, and flag were exclusively used in the posts falling into the category of nationalistic imagined community. For the religious imagined community, the exclusive elements were sacred texts, rituals, mosque, ummah and sacred place. Lastly, for the diasporic imagined community, the exclusive elements were language, nostalgia, shared culture, community centers and shared activities. The common elements that were adaptable to each category were as follows; including and excluding, shared experience, we-feeling, symbol, solidarity and potential enemies.

As mentioned before, the prominent subjects in these posts were the marginalization against the Turks in Germany and collective solidarity and support among the diasporic Turks against this marginalization. In this particular Facebook page, the admin(s) tends to share the negative contents which might draw reaction from the followers. According to the results we obtained from this page, it is safe to assume that, the case of being aggrieved is a way for the Turks in Germany come together, on an online platform. The page functions as an online platform for the diasporic community to come together on the adverse experiences they encounter as the diasporic identities. In this case, in order to marshal this community together, the page reminds them of their ethnic background, Turkishness; their religious opinion, Islam; and their status ausländer (foreigner).6 It is accurate to say that, this Facebook page makes use of the marginalization as a common ground, in order to make them a part of the nationalistic, religious, and diasporic online imagined community.

Nevertheless, the source of the post is as important as the post itself in determining the online imagined communities. Only a few of the posts containing diasporic elements were original contents and the remaining were the ones shared from other accounts/pages/groups on Facebook. The sources of the shared contents herein also gain prominence; because eventually, whom the admin(s) decides to share from, also contributes to the online imagined communities being structured on the selected page. The followers of the selected page engage with the posts from the sources, thus the admin(s) selects the contents and structures the imagined communities on behalf of them. What we encountered by reviewing the sources was that, almost all of them produced and shared nationalistic, Islamic, and diasporic contents. Besides, the selected page was not only interacting with Turkish-German Facebook accounts/pages/groups, but also the Turkish-Belgian and Turkish-Austrian ones. Videlicet, the selected page coheres its followers with nationalistic, religious and diasporic contents. The sources that the admin(s) chose to share from, revealed their point of view and the imagined communities they were structuring on the page. Turkish nationalism, Islam belief and diasporic issues were the main topics that the selected page was feeding itself.

It is clear that the posts and the sources play a fundamental role in structuring an online imagined community. As for the elements of this structure, it is known that language is one of the most important elements (First, Avraham, 2007, p.229). Usage of language is important for the structure of diasporic imagined community as well, because it serves a strategy among the diasporic community, not only to maintain a transnational identity but also to construct a unique identity in the recipient society (Woldemariam, Lanza, 2015, p.172). While some posts were monolingual and some others were bilingual, the languages used mostly were Turkish and German. Using two languages as the main ones indicate that this page was formed for the people who were able to understand both, namely the Turkish-Germans. Therefore, these languages served as one of the foundations of this online diasporic imagined community. Especially the bilingual posts were understandable for all diasporic generations because they overcame the difficulties caused by differences in linguistic skills of the first generation and the third generation. Although Turkish was an element of their nationalistic imagined community, using it together with German made the posts and consequently the page, a part of diasporic imagined community, because even though their homeland was Turkey, they were residents of Germany.

First and Avraham asserted that, land and national identity can be intertwined (Avraham, Daugherty, 2012, p.1386). Since land is an important aspect of the imagined community, it can be said that, the places in the representation of the posts, become an element of the online imagined community due to the fact that the media representations of the land symbolize the interaction between land and social identity (Avraham, Daugherty, 2012, p.1386). When we examined the posts within this context, we saw that Germany and Turkey were the places in the representations. It can be clearly seen that the posts, in which Turkey was the place in representation, were all linked to the diasporic Turkish community. That is to say, the place in those posts were used to demonstrate the Turkish-Germans’ ties to their homeland. Turkey, as a place in those representations, indicates the Turkish-Germans’ part in the nationalistic and diasporic imagined community on an online platform, where they observed the actual events and incidents from far away and, shared the experience by means of engaging with the posts. However, Germany as a land constituted the majority. Unlike the established relationship with Turkey, Germany functioned as a place where the diasporic Turks shared similar experiences and, these experiences made them a part of an imagined community through this Facebook page. Because the contents of the posts showed that on this particular Facebook page, Germany was represented as a place where the diasporic Turks were being marginalized.

In the subcategories we discussed above, we tried to determine how the admin(s) of this particular page was constructing an online imagined community for the followers. We examined components such as language, place in representation, the sources of the contents, and the main subjects of the posts. However, in order to determine the categories of imagined communities, we looked for specific elements explained in the theoretical and the methodological section. When we analyzed the posts, which constituted nationalistic, religious and diasporic online imagined communities, we searched for certain elements. Within this particular context, in order to constitute an online imagined nationalistic, religious and diasporic community, there were some prominent elements.

Sharing nationalistic discourses online

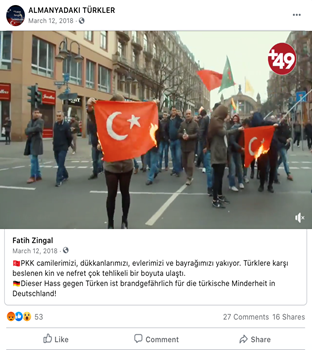

According to the data we obtained, there were some main elements needed to construct the nationalistic imagined community containing the diasporic constituents. The prominent elements7 were flag, land, we-feeling, including and excluding, ethnicity, and political leaders. These elements were used in speeches, visuals, texts, and symbols.

Flag is one of the most important aspects of a nationalistic imagined community and moreover, it is a sacred symbol for the Turks (Seufert, 1997, p.59). The flag is ubiquitous in Turkey (Bora, 2003, p.438); however, in Germany it is not likely to see a Turkish flag too often. Seeing their national flag on an online platform, arouses the feeling of being a member of the nationalistic imagined community for the Turkish-Germans (see pictures 1 and 2).

On the other hand, since they were away from their homeland, by seeing the land as an element on this Facebook page, they get to be a part of the same nationalistic imagined community with the Turks in Turkey. At this juncture, ethnicity also gains importance. The particular community is considered neither as “real Turks” (Robins, Morley, 1996, p.248), nor “real Germans” (Pusch, Splitt, 2013, p.153), so expressing their ethnicity loud and clearly on this Facebook page as a part of the Turkish community also legitimates their place in the nationalistic imagined community.

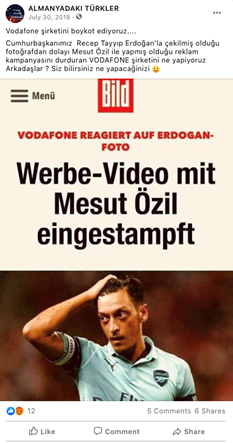

Sharing posts about the Turkish political leader serves the same purpose, because through these posts, Turkish-German society could show their engagement with the Turkish politics, thereby the national imagined community (see pictures 3 and 4). The elements above could be considered as the tangible elements, as opposed to the intangible ones such as including and excluding, and we-feeling. These two elements create a sense of togetherness and association between them and the Turks in Turkey and play an important role in the nationalistic imagined community. Because both the “we-feeling” and “including and excluding” involves a link with the Turks in Turkey.

According to these results, it is safe to state that this Facebook page uses certain elements to constitute an online nationalistic imagined community for the Turkish-Germans. These elements in visuals, speeches, and texts, not only designates a specific imagined community but also make the followers a notable part of it.

Religious discourses on the page

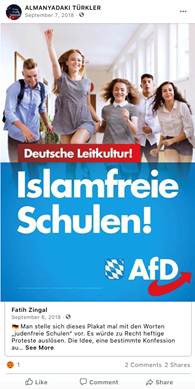

The Islamic Ummah is an important imagined community for the Muslims (Anderson, 2006, p.13). In this study, we examined the posts that address to the diasporic Muslim Turkish community in Germany. The results we obtained were very similar, in terms of the components, because nearly all the posts contained the nationalistic elements as well. Therefore, we focused on the main subjects and the religious elements of the posts. The main subjects were, as mentioned before, the marginalization against the Turks, collective solidarity and support. However, as it was understood from the contents of these subjects, the marginalization was against the Turks because of their belief. Videlicet, it was against the Muslims, but since the majority of the Muslim community in Germany were Turks (Chbib, 2010, p.18), they became the target group being affected by those actions.

There were nine elements that were used in 15 posts. The prominent elements were ummah, rituals, mosque and symbols. These elements were used in speeches, visuals, and texts. Primarily, in order to construct an online religious imagined community, this page created an online ummah by means of sharing certain posts displaying the Turkish-Germans’ religious opinion. For any follower of this page, the Turkish-Germans’ part in the religious imagined community became visible through the Islamic symbols.

Due to being performed five times a day, praying and performing salaat could be considered as the most important and the oftenest rituals of the Islamic community (Aydın, 2009, p.88). This page, makes the followers a part of these rituals by sharing prayers and verses from the Koran, and by doing so, t structures the religious imagined community. It may well be argued that mosque, as an element of an online religious imagined community, has the same function as the rituals. The reason why we associated mosques with the rituals is because mosque is a place to perform the rituals and pray. The mosques are not very rife in Germany, for the diasporic people to visit and practice their religion, compared to Turkey. Therefore, instead of seeing a mosque in almost every neighborhood as is the case with Turkey, they see the images or videos of mosques on this Facebook page (see picture 5). The page provides the followers a chance to encounter with the Islamic images and texts online, and fill their void of belonging to the religious imagined community.

In this context, religious symbols’ function is very similar with the elements mentioned above. Especially the Islamic symbols of appearance such as hijab (see picture 6) or rounded-beard directly demonstrate the people’s religious opinion (Çoban, 2015, p.63). Introducing the Turkish-Germans with the Islamic symbols, reveals that the page is acknowledging them as a part of the religious imagined community and constructing it through the posts containing these symbols. The followers get to see that even though the Turkish-Germans are away from a Muslim country, they are still expressing their part in the religious imagined community using the symbols. The most comprehensive element of the religious imagined community, identified on this Facebook page was the ummah. It was seen that, in order to create an online ummah, the page tended to share the negative behavior towards Muslims, which might draw attention of the followers. Hereby, through the we-feeling, including and excluding, the page aimed to gather the ummah together on an online basis to share certain reactions which were initiated by the page itself. According to these results, it was safe to state that this Facebook page used the certain elements to constitute an online religious imagined community.

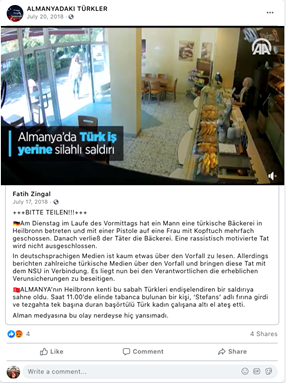

Diaspora 101: Diasporic discourses within the posts

According to the data we obtained, there were some prominent elements used to construct the diasporic imagined community. These elements were language, we-feeling, shared experience, community centers, shared activities and solidarity. These were used in speeches, visuals, texts, and symbols. The importance of language in forming an imagined community was mentioned before. Turkish-German identities are mostly bilingual; and the linguistic competence of the Turkish diaspora is improving with each generation. However, it is known that they still use Turkish in their daily and social life (Kırmızı, 2016, p.150). Furthermore, being bilingual became a part of their diasporic identities. Switching between Turkish and German is intrinsic to Turkish-Germans since they are able to express themselves better by using each language (Kırmızı, 2016, p.150). It was seen that, some posts on this page were in German, some were in Turkish and some were bilingual (see picture 7). The page constructed its online diasporic imagined community by using two languages separately or together, just like the Turkish-Germans did in their daily life. The page was creating an online diasporic imagined community through the language usage. Bilingual language usage was engaging them with Germany while maintaining a link with their homeland, thus this usage allowed the followers to feel as a member of this diasporic imagined community on an online basis.

All other prominent elements except the language were contextually similar. They were all related with togetherness and association, unity and solidarity, communion and congregation, and corporeally aggregation in social life. It was seen clearly that this Facebook page showed the Turkish-German society as an accompanying community. The posts that containing diasporic elements were mostly about either the marginalization against the Turkish-Germans or the solidarity amongst them (see picture 8). At this point, the we-feeling identified in the posts showed that, the page was incorporating its followers to this society by means of using the word “we”. Because in the posts examined within the scope of the study, the word “we” involved not only the Turkish-Germans, but also the followers of the page. By adumbrating the we-feeling to the followers, the page made its followers ready to create a common reaction and solidarity. Through the sense of we-feeling in the posts, the page indicated its followers that, what was happening towards the people were not against an individual person but against the Turkish-German community. In this regard, shared experience and shared activities, have similar roles because they are based upon the concept of we-feeling.

Shared experiences are important for constructing the imagined communities, and it was stated that, experiences create a sense of community (Been, Arora, Hildebrandt, 2015, p.93). In this case, sharing and receiving experiences on a digital platform, helps to create an online imagined community. On the other hand, the page was sharing the posts about the attitudes towards Turkish-Germans. Since the marginalization was not against one individual but against the community itself, the experience became a shared experience among all Turkish-Germans. Those experiences made the Turkish-Germans to start acting in solidarity because, shared experiences motivate them to care about the idea of imagined community and make things happen together (Howell, 2002, p.94). The concept of shared experience became two-edged on this Facebook page in creating the online diasporic imagined community. First, the experiences of Turkish-Germans were shared on this platform for the followers to act in solidarity. Second, the followers share their own experience once they saw these posts.

The posts about solidarity were about eirenicon for the Turkish-Germans and/or revealing the unity amongst them. These two components formed an element together by prompting the followers to act in solidarity with the other Turkish-Germans. The page’s function at this point was to allow the followers to come together on an online platform to act in solidarity, and thereby to construct an online imagined community. It can be stated that the page functioned as a virtual community center where the people came together to exchange opinions. As for the community centers, it was argued before that there was an interrelation between the tangible and virtual elements. This page undertook the role of community centers and fulfilled it at a digital platform. By sharing posts about the community centers, the page revealed the existence of them. The idea of an imagined community got clinched by seeing various community centers on the page pertaining to Turkish-Germans. Therefore, by informing its followers about those community centers, the page got to construct an online imagined community.

Those community centers are shared places where the diasporic Turks not only get together but also participate in the activities such as celebrations, commemorations, festivals and manifestations (Gorp, Smets, 2015, p.73). The shared activities help for the Turkish-Germans to construct both diasporic and nationalistic imagined communities depending upon the subjects of the posts. According to the data we obtained, it seemed that there were two ways for Turkish-Germans to share an activity which are reacting and rejoicing. Reacting as a shared activity was amongst the diasporic identities about the issues of diasporic society, therefore it helped to construct the diasporic imagined community. Rejoicing, on the other hand, was about the events happening in Turkey, therefore it helped to construct the national imagined community. By carrying these shared activities on a digital platform, the page allowed its followers to engage with them, and as a result the page constructed an online diasporic imagined community.

Conclusion

Facebook and especially its groups and pages, play an important role in gathering people virtually to maintain relations with the other members of the imagined community. These pages and groups have become a rather convenient platform for the diasporic people to forgather and contact the other members of the diasporic community. Although Facebook’s role in constructing an imagined community for diaspora has been studied previously, there remains a need for understanding how Facebook is being constructed for this aim. In this study, we examined the elements and components of a Facebook page that created an online imagined community for Turkish diaspora in Germany by using Anderson’s (1983) conceptual framework. We selected a Facebook page called “Almanyadaki Türkler” and analyzed the posts shared on this page in a one-year period. We conducted a textual analysis of 33 posts shared between January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2018, and in our analysis, we paid specific attention to the diasporic elements in the posts.

In line with selected elements to construct an imagined community, the findings of this study revealed that the selected Facebook page was using certain elements to form an online diasporic imagined community. According to the results we obtained from this page, it is safe to assume that, the case of being mistreated is a way to gather the Turks in Germany together, on an online platform. In this case, in order to marshal this community together, the page reminded them of their ethnic background, Turkishness; their religious status, Muslimism; or their social situation, being a diaspora. It may well be argued that, in these diasporic posts, nationalistic and religious elements were frequently used to indicate the followers the cause of the marginalization. As a result, the followers of the page could be in tendency to form an opinion about being a Muslim Turkish diaspora in Germany, which paved the way for the otherization, because of the representations in the posts. On the other hand, due to the subjects and the places of the posts, it can be seen that the connection with the homeland was not likely to be broken. The page stiffened the nationalistic and religious feelings via the posts and also, reminded the followers of the reality of being a diaspora through the main subjects. The page functioned as a virtual zone for the Turkish-Germans and so, it created an online imagined community through the content and structure of the posts.

In this study, we argued that the Facebook page itself created an online imagined community and thus the people became a member of this community by following the page; because the admin(s) predetermined the subjects, components, and the elements to be shared on behalf of them. Therefore, especially for the posts that were not originally created by the admin(s), but shared from other sources were essential in this study. As a result, we found that this page was using the sources which were glorifying Turkish nationalism and Islam religion, and in some cases Turkish-Germanness. Consequently, the followers encountered with these predetermined posts, and thus assumed to be a part of those imagined communities. Original or shared, the great majority of the posts contained a political statement about nationalism, religion and diaspora. Especially the posts containing diasporic elements and the language usage on the page as well made this page pertain to Turkish-Germans. Using two languages, separately or together, helped to create an online imagined community for the diasporic followers. Using two places along with languages, had the same function. In majority of the posts, Turkey and Germany were the places in representation and thus, the diasporic followers of this online imagined community could establish a connection with both those places as their home country and host country.

We argued that, on the page, the elements for constituting the online imagined communities were as important as the components of the posts mentioned above. The three imagined communities that were constructed on this page had nationalistic, religious and diasporic discourses. In order to form the nationalistic online imagined community, the posts on the page contained flag, we-feeling, including and excluding, ethnicity and political leaders. These elements indicated that the page constituted nationalistic online imagined community for the diasporic followers by means of the discourses of association and loyalty to the roots. In order to form the religious imagined community, the posts on the page contained ummah, rituals, mosque and symbols. These elements indicated that in order to constitute a religious online imagined community for the diasporic followers, the discourses were associated with the Muslim community and the religious duties. In order to construct the online diasporic imagined community, the posts on the page contained language, we-feeling, shared experience, community centers, shared activities and solidarity. These elements indicated that, the imagined community was built on the discourses of the selective features of Turkish-Germans and their solidarity and association as a community.

In conclusion, in order to constitute an online diasporic imagined community, this Facebook page was using specific topics, components and elements. The page constantly reminded its followers of their ethnic background, religious views and current situation. However, it also linked the diasporic people with their home country rather than their host country by sharing negative contents about Germany, while the posts about Turkey contained positive contents. Overall, the elements used to make three online imagined communities had major common points; association and solidarity. Eventually, we could state that this page served as a medium for constructing an online diasporic imagined community for the Turkish-Germans and to reach this end, it used the unity, being mistreated, and the components pertaining to the Turkish-Germans.