Introduction

This article aims to analyse a renowned live television event from the perspective of co-viewing in connected social media platforms and to look at how co-viewing practices might be shaped by the affordances of these platforms. The study takes the Eurovision Song Contest as a case study due to its long-standing popularity, tradition and its capacity of sparking co-viewing practices in different social media platforms.

Co-viewing is considered a peer phenomenon (McDonald, 1986) that allows viewers to exchange their impressions of a TV show, as well as learn and enjoy from it. Co-viewing impressions can be grounded in the viewer’s expectations about the show and their genre (Pires, 2018a). In Co-viewing, as in Cultural Studies, there is an explicit aim of avoiding “traditional approaches that tended to view the audience as passive or simply not included as a subject of inquiry.” (Pires, 2018, p.411).

Television has always been a social device. Indeed, TV broadcast has served many different purposes in audiences’ daily routines (Silverstone, 1994; Lull, 1990). However, it was not until the rise of social TV applications supported by digital technologies and a more social structure of the Web that this sociality started to have a broader appeal (Chorianopoulos & Lekakos, 2008). Since then, social TV was widely studied. However, no single shared definition was agreed. As Selva (2016) points out, some studies focus only on technological interaction generated by second screen apps and television systems, while others on the social practices of audiences online. In this study, we consider co-viewing practices to be social television practices that can be shaped by co-viewers, their activities, and the technologies used therein to co-view. As we will see in this article, co-viewing practices are usually triggered by specific events and institutions, such as the premiere of a TV show, a series finale or a live broadcast event with a large following that happens within and outside the scope of connected platforms. These sorts of practices can generally get boosted by online data traffic in different platforms and social network sites (Bechmann & Lomborg, 2013). The Eurovision Song Contest, also referred only as Eurovision or ESC, fits in the category of live events that can activate co-viewing practices in multiple manners along with the use of online backchannels (Doughty, Rowland & Lawson, 2011). Due to its long-running tradition, Eurovision viewing activities have been extended to connected platforms, such as Twitter (Highfield, Harrington & Bruns, 2013), an official Eurovision second screen app and other connected spaces. Therefore, we hypothesise that a ritual of a transnational televisual event, such as the final of Eurovision is a privileged space for studying different co- viewing practices. Besides, it allows for a better understanding not only of audience behaviour during a prime time live event, but also of the affordances (general and specific) of the social media platforms where co-viewing occurs.

In this study, we took Eurovision in the Spanish context to study co-viewing, being one of the European Broadcasting Union territories with more conversation about the contest, and the main non-English language cluster community (Highfield, Harrington & Bruns, 2013).

Because of the temporal dynamics of events such as Eurovision, which reclaims the televisual time (Evans, 2015), a case study method has been applied to understand the continuities and novelties of co-viewing in the connected viewing context (Holt & Sanson, 2014). Our main objectives are to observe the entanglement of co-viewing practices with the affordances of the Eurovision second screen app and social media platforms where Eurovision is co-viewed. We also scrutinize the sense of communal liveness fostered by social media platforms, particularly Facebook (through an unofficial Facebook group where an actual conversation was encouraged and monitored by fans), Twitter (through event-related hashtags) and user-generated content (created or shared on the fly). This is because we aimed at understanding the ways connected co-viewing practices can be shaped with the use of a second screen app and social media platforms. These platforms have different affordances by default and others that can be applied by their users. Through our research, we have addressed the following issues: (1) the manner in which co-viewers materialize their co-viewing practices within social media platforms (2) how a second screen app affordances encourages or discourages co-viewing (3) the way in which social media platforms shape co-viewing.

We collected empirical data from four sources: (a) participant observation process of the official second screen app during the final, (b) observation in real-time of an unofficial Facebook group dedicated to the contest and (c) conversation on Twitter around broadcast; d) data extracted from the official app reviews, in search for affective response related to the app’s affordances.

Origins and academic interest

Eurovision has been airing for more than sixty years through the European Broadcast Union and is one of the world’s oldest television shows still running. According to Carniel (2017), Eurovision’s origin can be situated around the need for a recreation of a collective imaginary of a united Europe in times of Cold War. Since its inception until the present day it somehow shows the shifting geopolitics of Europe, of its neighbouring countries and beyond - case in point is that of Australia that participates in the contest since 2015. Therefore, most of the audience studies related to Eurovision, unsurprisingly tend to focus on the interwoven socio-political issues related to national identity (Danero, 2015; Ismayilov, 2012; Sandvoss, 2008; Miazhevich, 2017) or multiculturality (Carniel, 2017), among other issues related to politics and nationalism. Nonetheless, we have opted for a different approach, concentrating on the various kinds of co- viewing practices sparked by this event with the use of connected platforms. This does not mean that issues like nationalism cease to be relevant in this context. Eurovision viewers have a clear complex national and pan-national affective relation with the contest. This is clearly noticeable in some observed practices that correspond to what Kyriakidou et al. (2018) label as “playful nationalism”. Playful nationalism is enacted when fans of the contest display their national flags as a background for communication with other fans, while they can also wave other flags to show support to favourite songs and their respective country of origin (Kyriakidou et al., 2018, pp. 609-610). Thus, without downplaying the role nationalism has in the Eurovision contest, we want to contribute to the study of Eurovision Song Contest considering the still scarce field of work dedicated to understanding audience activities related to Eurovision on social media and second screen apps (Highfield, Harrington & Bruns, 2013; Vanattenhoven & Geerts, 2017). Besides, our research dialogues with studies that look at other aspects of the contest, such as the use of humour, playful nationalism and ironical detachment, as mentioned in the Twitter study by Highfield, Harrington and Bruns (2013), in the onsite ethnographic analysis of the 2014 edition held in Copenhagen (Kyriakidou et al., 2018) or in relation to the analysis of homophobia and national identity in the former Soviet republics (Miazhevich, 2010).

Eurovision, as Bolin (2006) explains, shares many characteristics with other international media events such as the Olympic Games or the Football World Cup. It has competition at its core, which stimulates engagement. One particularity of Eurovision as an event is that it counts among the few ones conceived as a broadcasting event from the very beginning (Katz, 1980). Nonetheless, Eurovision is a noticeably contested event, being looked down in some circles as a decadent, kitsch and stereotyped show regarding music formulas, performance, costume styles and subjected to favouritism among neighbouring countries (Highfield, Harrington & Bruns, 2013).

Current organization of the Eurovision Song Contest

The Eurovision Song Contest is regularly celebrated every May and captivates millions of viewers from the European Broadcasting Union countries and beyond. According to the official Eurovision website, the 2018 edition attracted around 186 million viewers, and Spain was one of the biggest markets of the contest, almost doubling its 2017 audience and having 6.4 million viewers with a Share of 42.2% (Groot, 20181). It is interesting to note that the 2019 edition showed a noticeable decline, with 5,9 million viewers and a Share of 36,7% (Forte, 20192) - no comparative data can be drawn from the 2020 edition due to the Covid19 global pandemic.

The current European Song Contest follows a regular format that has evolved with time, and it is ideal for analysing co-viewing practices within a connected context. Similar to political debates, Eurovision offers a space for connected co-viewers to feel part of an unfolding event with social significance (Thorson et al., 2015). The competing countries that are members of the European Broadcast Union (not necessarily European Union members) must select a contestant and write an original song to represent them during the contest. Since 2004, it has been divided into two semi-finals and one final (Carniel, 2017). The so-called “Big Five” (Spain, Italy, Germany, France and the United Kingdom) is a privileged group that is automatically classified to the final, as they are the primary financial contributors of the European Broadcast Union (Highfield, Harrington & Bruns, 2013). All the countries have to perform their songs live in the host country, which usually is the previous year winner. The viewers’ participation is done via a voting system, in which neither national juries nor individual voters are allowed to vote for their own nation’s contestants (Jones & Subotic, 2011). Since 2016, the voting system has been split between jury and popular vote. Therefore, as we have observed, in 2018, there were two rounds, jury (the traditional awarding system, leading to a provisional classification) and televote, which was combined to obtain the definitive classification, and therefore, the winner.

We consider that the format of Eurovision and its voting system are crucial for analysing the variations of co-viewing practices. This is because we understand that this format can spark engagement towards the contest and between the co-viewers, which generates a broader social climate of participation. Furthermore, the 2018 contest slogan "All aboard!” echoed inclusivity and universality, highlighting implicit values attached to the contest. It also pointed to the effort in taking the experience to different media and platforms, made explicit through the app design, and its connections to social media through hashtags, as we will see later on in the analysis.

Therefore, we chose the 2018 Eurovision edition because it implied the consolidation of the use of the second screen app with improvements since its release in 2013. Besides, as the edition occurred in Portugal, we could experience the high expectations Eurovision had in Spain due to cultural and physical closeness to the hosting country. These expectations were further built up with the success of the 2017 winner, the Portuguese Salvador Sobral. Additionally, the Spanish representatives Amaia and Alfred were already famous because Amaia won the popular talent show Operación Triunfo (Star Academy) that year.

Co-viewing and Connected Co-viewing

In 1970, Ball, Bogatz, Creech, Ellsworth and Landes3 3carried out a seminal study about co-viewing, resulting in the report on how children who watched Sesame Street in a social context (usually accompanied by their mothers) improved their situated learning skills. Ever since then, co-viewing has been defined as a peer activity that enhances the viewing experience through negotiations of meaning while watching television (McDonald, 1986). Additionally, different studies have aimed at understanding how co-viewing happens in a different social and demographic setting (see McDonald, 1986; Lull, 1990, Paavonen et al., 2009; Banjo et al., 2017, among others). These studies demonstrate that different groups with varied social demographic features also perform co-viewing.

In its more traditional sense, co-viewing refers to a group of people collocated in the same physical space, who discuss media content (Pires, 2018b). During the co-viewing process, viewers can exchange their impressions of a TV show, which can be grounded on their expectations and previous experience and may even discuss related social and technical issues (Pires & Roig, 2016). The connected activity of viewers started to be considered in coincidence with the popularization of the Internet and the World Wide Web. However, co-viewing and other viewing activities with distant peers, as well as audience participation, are not new phenomena (e.g., as in the case of landline calls or conversations via computer chat systems). In any case, it is relevant to understand how they are evolving in a context where media content is distributed and consumed in various formats, devices, platforms, and are intertwined with multiple social practices (Araújo & Pires, 2016).

Holt and Sanson (2014), supported by a body of research developed by the Carsey-Wolf Center’s Media Industries Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara, named the current media context ‘connected viewing’. They defined connected viewing as a term that “refers specifically to a multiplatform entertainment experience that relates to a larger trend across media industries to integrate digital technology and socially networked communication with traditional screen media practices.” (Holt & Sanson, 2014, p. 1). The connected viewing context changes the way we access media content. Television used to be the main appliance for content access. In this context, television still is one of the big players, but media content can also be accessed and spread across multiscreen and multitasking environments: streaming viewing, on- demand viewing, and forms of social interaction through social media, second-screen apps, and instant messaging apps during traditional broadcasting (Pires, 2018).

The symbiosis between these new forms of television viewing with traditional ones, infrastructures, platforms, and devices available in the connected viewing context contribute to the reinvention of co-viewing in its connected manner. Thus, in this study, we consider connected co-viewing to be the practice of co- viewing an audiovisual content with (accompanied by) and within (inside) a connected platform, apps and second-screen devices. Since, connected co-viewing was further facilitated to occur between large numbers of viewers, as these platforms have mainstream usage and support backchannel communication (Lee & Andrejevic, 2014). In that sense, co-viewing can happen more often than before i.e., traditionally with peers that are at the same physical location, with peers in an offline setting and with others online, alone but in the company of online peers (Pires, 2018).

Nonetheless, new co-viewing practices can emerge when using other kinds of screen devices and social media that weren't available in the first years of the Internet. Cohen and Lancaster (2014) detected that when co-viewing in a social media, viewers are provided with the possibility to access other audience members with similar tastes, as well as to access a larger pool of social information to process during the televised event. This was also shown by Thorson et al. (2015) who detected that watching a socio-cultural event online with others amplifies the feelings of being connected to this event, thereby improving the sense of belonging to a like-minded group.

Methods

A case study methodology was implemented in this research because the knowledge it produces is experiential, contextual, and can be marked out through circumstances of the occasion when and where it is being studied (Stake, 2005). Also, it is appropriate when the researcher has little or no control over the events that are under investigation, as it allows the usage of multiple sources and techniques to gather data to understand the object of study (Thomas, 2015; Stake 2005). Furthermore, it allows for implementing a triangulation of methods. That is to say, “to obtain more reliability, as during the period of study, descriptions and interpretations are not done in a single step” (Pires, 2018, p.414), and multiple data gathering methods are allowed. Triangulation of methods involved synchronous exploration through extensive use of the app, including image and video capture with a time-stamp, online observation, and data mining from Twitter.

We looked at connected platforms as digital spaces where real-time and dynamic human practices such as co-viewing can materialise (Kitchin, 2014). Therefore, it was decided to carry out the observation during airing time. Subsequently, the mined data served as a way to contrast and reflect on preliminary observations. During the study, one of the researchers focused on the collocated co-viewing with the official app and Twitter use, while the other focused on scrutinising co-viewing within the unofficial Facebook group. Key impressions were shared through instant messaging.

The online observation of connected co-viewing activities was done within an unofficial Facebook group of Spanish followers of the Eurovision Song Contest. To be accepted in this group, it was necessary to reply to specific questions to prove the user was a person and to show a minimal knowledge about the contest. In order to conduct the observation, the researcher presented herself as such, emphasising that no names would be used for the purposes of the research. As the researchers intended to become part of the group before the final, it was also possible to observe warm-up and post-viewing activities. The decision to study a Facebook group was based on their architecture of interaction that is more horizontal and directed to a conversation rather than information (Pires, 2017). In addition, it was driven by the will to observe a space set-up by co-viewers and not by a network. Usually, companies set their official spaces within Facebook by creating pages, as they have a more hierarchical structure, comparable to broadcasting’s one-to-many design, and allow the owners to have metrics from the users and their activities (Poell, Rajagopalan & Kavada, 2018). Therefore, the focus was an unofficial group. As shown in a previous work in unofficial Facebook groups (Pires & Roig, 2016), the Facebook group can function as a space to avoid the co-option of the event promoters, even if, paradoxically, they are still a part of a powerful corporation like Facebook. On Facebook, we have hand-recorded screenshots from the unofficial Facebook group, as its application program interface does not allow mining data for closed-groups (Pires, 2018).

The app analysis was conducted through different techniques: firstly, through personal interaction during broadcast time by the authors, taking written notes plus extensive screen and video captures. Secondly, it was done through simultaneous observation of interactions with the app. This served to detect unexpected uses that better characterise the app’s affordances, particularly those functionalities that could only be observed in real-time. Subsequently, asynchronous in-depth analysis of available app features after broadcast time was conducted to wrap up the observation process. Finally, through data coming from the reviews of the Android version of the app, which allowed to collect dedicated users’ impressions of the app a week after broadcasting. We have mined data from Twitter with the NVIVO plugin Ncapture, plus Boolean search through TweetDeck, and used NVIVO 10 to categorise emerging themes. Finally, data of the reviews of the Eurovision official app in Google Play was extracted using the Data Miner Google Chrome extension, in order to compare with synchronous observations.

Practice theory as theoretical-analytical tool

To analyse the ways co-viewers materialise their co-viewing practices and how they are shaped by second screen app’s affordances and social media platforms, we have used a social practice approach from the second wave of practice theorists (Postill, 2011) as our theoretical-analytical tool (Reckwitz, 2002; Warde, 2005; Shove, Pantzar & Watson, 2013; Schatzki, 20154). A practice approach allows us to understand the ways co-viewing practices are interwoven with materiality such as digital platforms. Besides, they show how practices have a two-folded meaning: practice as an entity and practice as a performance. In the first case, the enactment of the practice needs certain organizational norms and implicit or explicit rules. In the second case, once this organisation is assumed, people perform a ‘naturalized’ version of the practice (Schatzki, 1996; Warde, 2005). Practices can evolve through enactment, interrelation with other practices or challenges to its constitutional rules (in moments of conflict or crisis).

Practice needs a place to occur. This place can be a material environment or a digital one, such as digital platforms (Araújo & Pires, 2016). Therefore, depending on its setting, evolution of the practice can be channelled, prefigured or facilitated (Schatzki, 2015). Furthermore, a practice can be marked by time, and certain practices only exist because of particular temporalities (Schatzki, 2009) as it is the case of Eurovision co-viewing in the context of an annual broadcast.

Results

To facilitate the interpretation of the main analysis outcomes, this section opens with a table summarising the main differences of Eurovision co-viewing practices within Facebook, with the use of the ESC app and with live-tweeting in 2018. Table 1. summarises these differences in terms of viewing types each platform supports, the norms and points of views it generates depending on the platforms affordances and the uses given by their users, the features of user-generated content (UGC) each platform allows to incorporate during co-viewing and the kind of nationalism it embodies. In certain aspects, the platforms are different, while in others, they work very similarly in how they can shape co-viewing practices to occur.

Table1: Comparison Eurovision co-viewing with three platforms. Our source

| ESC APP | |||

| Type of viewing it supports | Group viewing | Individual and collective App use + group viewing | Individual use with imagined co-viewers |

| Norms and points of view | Selection: admins + Facebook affordances Horizontal view | Normativization based on the group dynamics | Interweaving of views because of the combination of hashtags |

| Used platform features for UGC | UGC (Coloured background, emojis, reactions, poll, gifs, embedded content). | UGC (Selfies + stickers) | UGC (memes, hashtags, gifs, news). |

| Nationalism | Playful nationalism | Playful nationalism | Playful nationalism vs global problems |

The differences and similarities present in table 1. are further expounded in three successive subsections (Co-viewing within an unofficial Facebook group, Co-viewing with the Eurovision App, and Co-viewing on Twitter) and in the Discussion section.

Co-viewing within an unofficial Facebook group

The studied Facebook group had the status of a closed group. As previously stated, becoming part of this digital space depended on validation by one of the three administrators through a series of basic questions. Moreover, administrators explicitly banned political debates or Eurovision hate in the group conversations. Although filtering did not entirely prevent unwanted interventions, questions were done to ensure the presence of co-viewers matching similar interests. Therefore, this set of practices promotes, as stated in the literature, a sense of connection with other like-minded people (Bayam, 2000; Bechmann & Lomborg, 2013). Most of the observation was concentrated during the co-viewing of the Eurovision final. Nonetheless, it was also possible to explore some pre- and post-viewing activities, which helped to better access how the group's administrators and members organised their activities by using some of the Facebook interface features and from other connected platforms. As Van Dijck (2013) points out, a company configures its platforms knowing that they are part of a wider ecological system that competes and has to collaborate with other platforms. Within Facebook, there are similar buttons used by other interfaces, such as share, like, and hashtag indexers. Also, other third-party content can be shared or embedded in it. Therefore, most of the pre and post-viewing activities were based on sharing news and other information related to Eurovision from multiple sources, including the Eurovision official website. Users solved doubts about the contest date and format, and they also shared and discussed curiosities about Spain’s rehearsals.

The Facebook poll was one of the features that was present in the users’ post-viewing activities, particularly to compare previous contests’ songs and check each other’s preferences. Although it is a feature from the Facebook interface that can be applied in a varied range of contexts, in this case, it remits to the format of Eurovision voting itself.

It is worth noting that the administrators were in part responsible for the way co-viewing occurred, showing that power relations are also part of unofficial connected spaces, which might structure where, how, and when co-viewing and other viewing practices take shape. Also, these power relations implied a kind of normativity and censorship. In the occasions when politics took control over conversations or posts, the administrators banned users, as there was “a place for enjoying spectacle and music”. The administrators were not the only responsible for structuring these activities. Other users and the way the Facebook interface is designed also channelled how these activities unfolded.

The space created for carrying out co-viewing practices of the Eurovision final on Facebook was prefigured by one of administrators of the Facebook group, who used the Facebook coloured background to set-up where co-viewing should occur. The coloured status background introduced by Facebook in 2017 (Constine, 2016)5, in which the text fonts get bigger to catch user’s attention was used to highlight the specific space where co-viewing should occur within this group. Thus, pointing that co-viewing, as many other practices, evolve with the use of resources, which can facilitate, channel and prefigure the ways practices take shape (Schatzki, 2015). This space was established as the “digital living room” with use of the following phrase: “The thread to watch the Eurovision Final is opened. Let’s go” plus the emoji with two hands raised in the air. Just before the broadcast, and during the first minutes, users expressed their expectations towards the contest, the countries they would like to win, and stated that “the most important was the spectacle and to have a good time”. The slogan “All aboard”, implemented by the broadcaster served the participants to inquire whether other co-viewers were present. Answers were given by using the same sentence in an affirmative form. Thus, concurring with the aspect that Cohen and Lancaster (2014) found about co-viewing within online spaces, usually done to feel a stronger sense of belonging to an otherwise geographically dispersed social group.

As Eurovision does not allow to vote for the same country one is geo-located in, the ten most active users self-identified to be in different cities of Spain, and two of them as living abroad. They showed their desire for Spain to have a good position and their support to other countries using the respective national emoji flags. Co-viewers acted similarly to what Kyriakidou et al. (2018) found in their study. They performed a non-national identification in a playful way with the use of other countries’ national symbols like a flag to communicate with other fans, rather than demonstrate an exclusive expression of nationalism and belonging. A clear example of that happened when the Portuguese contestant, Cláudia Pascoa, was about to perform. As shown in Figure 1., users were excited to see the neighbouring country perform and included the flag of Portugal and an emoji with hearts to express how much they like this country.

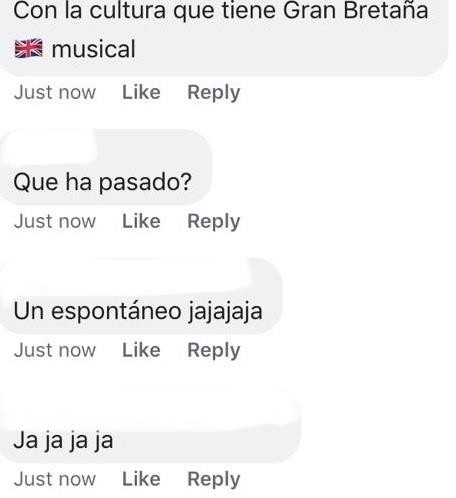

Emoji flags were recurrently employed by the users. Flag-waving occurred when a performance (according to users’ judgement) was “very good”, or was a “really beautiful song”, despite the contestant’s nationality. In Figure 2, one user ironically included a UK flag to contrast the country’s renowned musical culture and what was perceived as a poor performance. Other users agreed with this perception in surprise, while others just laughed about it. Moreover, users also used flags and emoticons to express that a performance came as a pleasant surprise, or when it was considered bad.

Background knowledge as a way to showcase expertise and authority among co-viewers is considered important in a highly codified format such as Eurovision. Thus, some interventions were related to the users’ perception of quality (performance: singing, melody, clothing, effects, choreography, etc.), but also comparison to previous editions of the contest.

During the Final, just ten dedicated co-viewers participated in the coloured status thread assigned to co- viewing. These ten users had the role of experts as they self-legitimised themselves and others as authoritative reviewers. Multiple ways of participating were identified during co-viewing: by expressing opinions, expectations, by sharing content with others (e.g. screenshots, jokes, and animated gifs, memes), and external links from Twitter, ranking the quality of the viewed content by using the Facebook reactions’ buttons, and by alluding to facts happening during the contest that was portrayed by other media - as it was the case of a stage invader during the performance of the United Kingdom singer.

The co-viewing conversation reached almost 500 comments, having user-generated content as a central element. Based on Shao’s (2009) definition of the three ways people engage with user-generated content (consuming, producing and participating), it was observed that the Eurovision unofficial Facebook group reached almost two thousand users, and only a reduced number of participants were participating (between five to thirty users depending on the day and time), and an even fewer users were using the Facebook features to produce content, mainly the three administrators and other sporadic users. Consumption was one of the main ways of engagement as it only requires information seeking, which evidences that co- viewing in a connected manner requires consumption because the more information that is available to viewers, the more the viewing experience can get amplified.

Content creation, or as Shao (2009) terms “producing”, occurs when users produce content such as videos, photos, stories among others. In some cases, co-viewers’ production can be very highly creative, by developing memes, mashups, recaps and other formats that stimulate meaning making. In other cases, creation can be rather mundane, or just derivative. The three group’s administrators were the main producers of content, though most of the creations were done with pre-set Facebook status and polls, as previously stated. Thus, the administrators were leader figures that determined the process of building a community of interest with the use of a varied range of UGC that weren’t intended to be necessarily creative, but rather informative and playful like the Eurovision format.

Users reaffirmed this playfulness of the viewing experience in various moments, by affirming the pleasure of living this experience with the other co-viewers, and by not having to discuss politics in this space. The need for belonging to a social group of like-minded people was also reinstated in various occasions, from the ‘All aboard’ welcoming messages to the final goodnight wishes and expressions of gratitude for sharing this moment together.

Co-viewing with the Eurovision App

The official app was structured in seven main sections: Home, Updates, Participants, OSRAM Light Voting (option unavailable after the event), Selfie Layer, Music Shop and Merchandise. The slogan and graphic design of the 2018 Contest, ALL ABOARD!, featured prominently on the app.

Most sections of the official app are either informative or commercially oriented. We were interested in those functionalities that pointed towards the addition of a participatory layer as a second screen tool (Evans, 2015), and therefore, which could favour co-viewing over an individualised experience: in this case, the Selfie Layer and the OSRAM Light Voting.

As a second screen app, there was an important synchronization with broadcasting time, particularly in the OSRAM Light Voting. During each performance, the app would switch to a default screen showing information about the performer and the country, along with song lyrics. The Selfie Layer was the only section that considered some social media activity during the event, as it allowed to take pictures with different kinds of virtual stickers. It was divided into three sections, with a ‘Share Selfie’ option at the bottom: Popular (9 sticker options), Flags (43 sticker options), and Countries (43 sticker options). Under the Popular label, it was possible to find a series of generalist stickers with the Festival logo, the current slogan or the host logo (in this edition, Lisbon). As for the other two, Countries show stickers more oriented to be shared to encourage the vote for a specific country, while Flags include each national flag inside the heart logo of the event, prompting different forms of self-expression of playful nationalism (Kyriakidou et al., 2018).

Initial interaction with the app focused on its different possibilities and key points of interest in terms of co- viewing, particularly all those related to the live broadcast, and therefore, ephemeral. After the early performance of Spain, Amaia & Alfred’s “Mi canción” (My song), we focused our attention and interest towards other functionalities, like the Selfie Layer. The Selfie Layer is an interesting example of what Keinonen et al. (2018) label as the ludic engagement of co-viewing. This refers to the fact that during collective viewing, people who watch talent shows with second screen apps tend to feel attracted to its most playful elements. The design of the Selfie Layer and its stickers seemed oriented to foster collective fun, creating personal content while playing with the logo of Eurovision or different country flags and/or creating personal memories. The Selfie Layer did not allow to save the content locally on the device, as it only allowed social media sharing. In this case, the affordances of the app consciously limited the practice towards a desired goal, that is, dissemination of content related to co-viewing through social media outlets, neglecting personal use, which can eventually lead to disengagement (Hill, 2017). We later observed that what we perceived as a potential limitation was also a recurrent complaint in the app reviews. The save option was available in 2015 and 2016 editions of the app but disappeared in 2017 already to an overtly negative reaction: users stressed the value of using the app as a way not only to share but also to keep a memory of the shared viewing experience. For the 2019 edition, the save option was again available, in a process of re-design where playful personal memories were deemed as important as social media sharing.

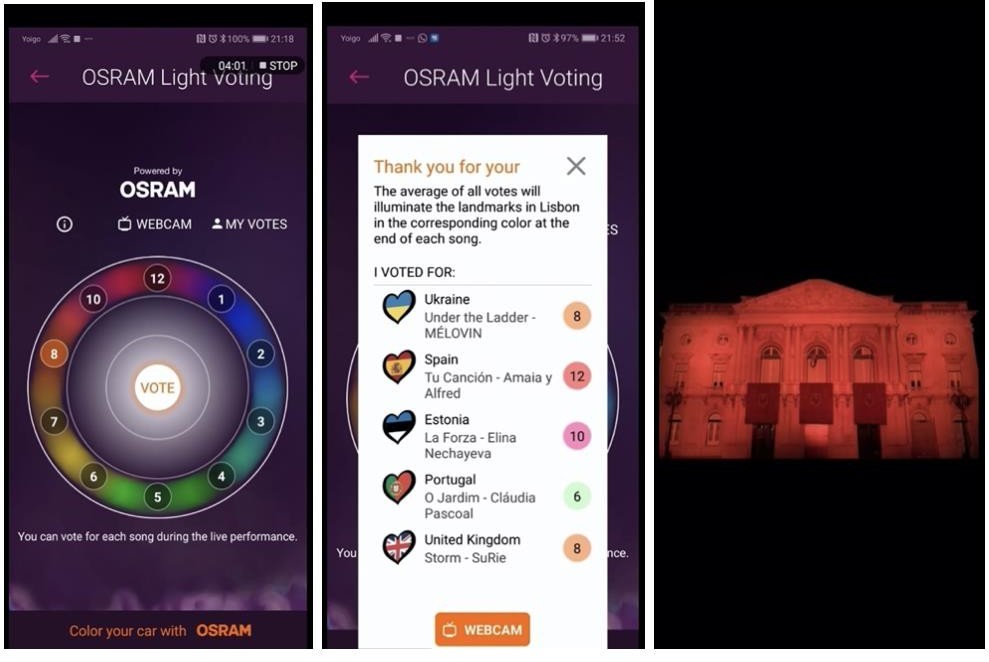

The OSRAM Light Voting section was designed to allow users to vote for the current live act during each

performance, independent of location. Nonetheless, these didn’t count as official votes. As shown in figure 3, they only contributed to generate a colour code (from blue to red) depending on the number of votes submitted. At the end of each performance, a landmark monument in the city of Lisbon lit up with the resulting colour, and that was visible in the app through a webcam view (thus the name of Light Voting and the sponsorship by German multinational lighting manufacturer Osram).

Even if the app emphasised the relevance of the OSRAM Light Voting, it became quickly evident that it was just a vicarious way to express preference, as the only official way to do so was through sending a paid SMS. Furthermore, this voting was ephemeral as was strictly synchronized with performance of the contestants, so there was no way to express interest in other songs in other moments of viewing, despite frequent replays during broadcast. In terms of design, replay functionalities during broadcast, plus previous knowledge of the songs could emphasise engagement in non-synchronous activities, which could complement broadcasting and enhance the co-viewing experience. This way the different television co- viewing practices which included non-synchronous activities, would enter in a mode of collaboration rather than competition, attending to the distinction stated by Shove, Pantzar and Watson (2012). Nonetheless, the app affordances were designed to keep users focused on the current performance with few distractions, either with fellow co-viewers or through social media. The initial impression, coming from live interaction, that co-viewers could feel let down was later confirmed by looking into app reviews. Another noteworthy element related to the voting process was the split between traditional jury vote and the public televote, which was presented at odds with other popular television events like talent shows. As we’ll see later, this disappointment was made explicit on Twitter, and was also a recurrent complain in app reviews, where users expressed their frustration with the voting system in the app, with the actual voting system seen as a “waste of time and effort”, “old-fashioned for a 21st Century event” and a “rip off”. Presented as a three stars app, filtering the average rate only for 2018, it fell down to 1,34, which is quite symptomatic of a negative perception.

Co-viewing on Twitter

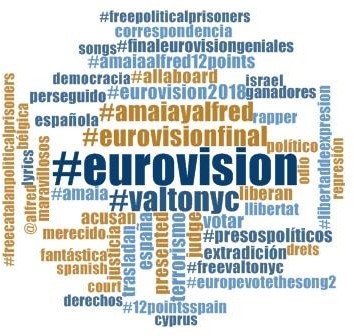

As it is well known, Twitter allows for a far broader and open conversation regarding the broadcasting topics defined by hashtags like live-tweeting activity (Schirra, Sun & Bentley, 2014), as there is no way to keep it behind gated doors like in the Facebook Groups. Therefore, in Figure 4. we have included a word cloud with the main hashtags and words that appeared in the data we have mined with the Ncapture plugin of NVIVO.

In an initial observation, a core of mainstream, descriptive and normative hashtags, like #eurovision, #allaboard, #eurovision2018 and #finaleurovision were identified, which made it easier to catalogue conversations regarding the event. On the one hand, these official Eurovision hashtags can be considered normative ones. That is to say, when they are created they have the purpose of an indexer (Bruns & Burgess, 2011). The goal is that all posts done related to the topic (in this case the contest) include the hashtag. On the other hand, there are hashtags that can be disruptive, as users can use them associated with the official ones for bringing to the fore other topics that can be political, social, with a clear claim that can challenge publics and their counterpublics (Kuo, 2018). Some hashtags were oriented to show support to Spanish contestants #amaiayalfred or #amaia, while others focused on encouraging Spain and particularly the vote of fellow European citizens, like #amaiaalfred12points, #12pointsspain, #europevotethesong2. Finally, there were other more disruptive hashtags, much less related to the event but used in conjunction with mainstream ones to bring the conversation towards other social and political issues. The most noticeable example was the set of hashtags used as a public protest regarding the repression of rights of speech in Spain in relation to the rap singer Valtonyc, who had been recently charged for insulting and allegedly threatening the Spanish Monarchy and the Police Forces and who had to leave the country. Thus, some users appropriated popular hashtags as an anchor to raise awareness for their cause, combining some of the mainstream tags with other ones like #libertaddeexpresion (freedom of speech) or #freevaltonyc. In the first observation, we also came across some critical tweets alluding to the political situation of Israel (the country which won the contest), even if in the Spanish context it was less relevant.

After this first observation, a more systematic exploitation of hashtags and combinations of hashtags of tweets uploaded during broadcasting was carried out, using the NVIVO software and the Tweet Deck platform in order to get a bigger picture. In this second round, conversations connecting the Spanish presence in Eurovision with the political situation in Catalonia was found, which in turn was frequently connected to Valtonyc (self-presented as a supporter of the cause for the independence of Catalonia). Like in the case of Valtonyc, hashtags like #freepoliticalprisoners or #freecatalanpoliticalprisoners were combined with the mainstream hashtags to bring up the topic.

Nonetheless, live-tweeting is not only used for cataloguing and shaping a collective audience but also for other purposes, from humour (particularly regarding individual performances), to express opinions and feelings regarding quality and preferences, predicting results, and the fairness (or lack thereof) of the voting results. In this sense, the quick creation of memes related to specific performances (Israel’s being a recurring target), or simply uploading screen captures from the broadcasting with sarcastic captions and hashtags, or even unrelated images able to trigger funny associations were some of the most used examples. Furthermore, other tweets were aimed at connecting the attention devoted to the event towards current social issues.

Discussion

While carrying out this study about the Eurovision co-viewing in a connected context, it was possible to identify that co-viewing is shaped by the affordances and features of social media platforms including dedicated second screen apps. We have identified that co-viewing can generate further engagement when the designed architecture of the used platform takes into account that co-viewing practices are enhanced with other intertwined everyday activities beyond synchrony with broadcast time. This was clearly the case with the Eurovision app’s Selfie Layer, which couldn’t be used for having an enriched souvenir of the experience: this shortcoming points either towards not taking into account the private dimension of the selfie practice, or towards a specific goal to maximize social media sharing while viewing. It is not surprising that after the backlash of 2018 this functionality was reintroduced in 2019.

It was also observed that asynchrony related to activities such as voting, discussions, negotiations of meaning and preferences can enrich this co-viewing practice. This was clearly seen with the Osram Light Voting. This is because different co-viewing practices, including those of non-synchronous activities are characterized by collaboration rather than competition (Shove, Pantzar & Watson, 2012). Without a clear understanding of users’ practices and possible synergies between co-viewing activities, the affordances of the platform might lead to gradual disengagement.

These platforms and apps can be considered “multitasking-facilitating media technology” that supports people to control when, where and how they consume media (Wang & Tchernev, 2012). Co-viewing implies talking, and in the connected manner writing, or even voting; therefore, it is a practice that requires that viewers simultaneously process information independently of synchrony. Thus, it may require that the co- viewer switches back and forth (Lang & Chrzan, 2015) to meaning-making of the multiple information acquired during this activity.

In the study, it was shown that the official Eurovision app was developed to focus on individual use. Moreover, as co-viewing is a group activity, the need to implement this kind of app with elements that favour viewing interactions was seen as essential. This observation is coherent with results of the study by Vanattenhoven and Geerts (2017), where an ad-hoc unofficial Eurovision app was designed and tested: playful elements of group co-viewing were added and proved valuable as assets to enhance co-viewing activity.

In any co-viewing environment, viewers select their group of like-minded people. Thus, co-viewing practices are subjected to different hierarchies regarding co-viewer relationships. In the case of connected co-viewing, these relationships can be established through different layers depending on the affordances of the platforms. As an example, Twitter does not establish a digital space for co-viewing, as was the case with the Facebook group and the coloured background set up by the group administrator, but generates a stream for co-viewing or live-tweeting driven by the use of multiple hashtags. This way, the normativity and hierarchy created by Facebook group administrators that shaped and imposed the way co-viewing practices should occur were not identified on Twitter. Co-viewing on Twitter is not restricted to group settings, opening greater possibilities to the introduction of controversial and confronting views or unrelated topics, such as the trial of singer Valtonyc or the arrest of Catalan politicians, as well as references to Israel and Palestine conflict. However, there are also serious concerns regarding censorship on Twitter, as it is the case of organized campaigns aimed at forcing the opaque Twitter algorithms to automatically suspend an account, through mass reports claiming about the offensive nature of specific content (López-Tena, 20176). In fact, some politically-charged tweets identified in the preliminary observation had been already deleted in subsequent data extractions, possibly to avoid suspension.

The centrality of user-generated content practice was present along the used platforms. It was possible to see that within the Eurovision app, users could create their selfies and vote. On Facebook, users shared third-party content, memes and animated gifs, while using the features of the Facebook interface (polls and coloured background) as a way of enhancing their viewing activity and indicating their viewing presence. On Twitter, opinions, memes, and several hashtags were applied with the aim of expanding the social circle of attention, either for co-viewing or to raise awareness of social issues. The findings of this study expose that in all the cases, co-viewing with the aid of connected devices and platforms is a practice that is impossible to dissociate from the practice of user-generated content. Thus, connected co-viewing implies that any activity takes shape as user-generated content and data.

Despite the fact that the designed architectures and features of each platform prefigured the way user- generated content happened, this prefiguration was also disrupted by the way users attributed meaning to their co-viewing and its interwoven activities. As an example, on the case of Twitter, viewers talked to imagined co-viewers with the combination of hashtags of their choice with the official ones released to follow the broadcast contest. The combinations of hashtags make different viewer contexts cross-cut: viewers interested in politics, national issues, vs. those that are fans and are only intending to have fun and perform playful nationalism. This crossing of viewer’s goals may lead a portion of the viewers to understand it as a form of spam (Bruns & Burgess, 2011). Furthermore, it was also possible to identify hashtags used in an emotional rather than an indexical way, or for expressing opinions about social justice, just like in social movements (Paparachassi & Oliveira, 2012).

Co-viewers who combine the use of various Twitter hashtags can crosscut the same conversation despite the user's own agenda and particular interest. This agenda crossing does not happen so easily in closed spaces like the Facebook group of Eurovision, as the administrators can apply the interface privacy features to impose a filter before users get to become part of the group. They do it by filtering the goal they decide the group should have. Therefore, in closed groups, viewers talk to other co-viewers because of their sense of belonging rather than imagining other co-viewers that would agree and resonate their agenda of interest.

Conclusions

The Eurovision case illustrates some relevant insights into the co-viewers social circle selection and normativity with the use of platforms. Firstly, Eurovision is a diversified event that allows intergenerational viewing, which is the basis for co-viewing. Secondly, it is a complex event that touches social issues such as nationalism, and socio-political issues. This complexity has allowed us to contrast the ways co-viewers can use features of platforms to protect themselves from those topics or to use them for opening a more extensive debate including issues that go beyond the entertaining nature of the event.

Furthermore, this article demonstrates that co-viewing is a techno-cultural practice that can be mutually reshaped by various agents such as co-viewers, the space (digital or non-digital) where it takes place, and by the affordances and architectures of connected platforms such as devices, apps, and social media. This is an important step for co-viewing since we come to understand that this practice can take different formats when using or carried on within connected platforms. Therefore, our study identifies the need to continue looking into the ways the co-viewing practice will unfold in other platforms in the near future.

Finally, studying co-viewing from a case study perspective combining both traditional and digital methods was essential to shed light on viewing practices and its entanglement with connected technologies and digital platforms’ architectures and features. We consider this approach potentially useful in other similar cases. Future research may include an event with a longer timespan, a comparative co-viewing in different countries or focusing on different kinds of co-viewing not marked by the broadcast time like binge-watching, or other second screen apps.