Introduction

The news industry is changing everyday as we see wide ranges of social media news sources gaining importance online. Social media news can be convenient and paired with smart devices means that they can be highly “shared” within minutes of their occurrence. This produces news content at a rate never imagined and at a greater quantity never reached; no fact checking and no editorial judgement whatsoever (Allcott & Gentzkow 2017). We started to question what was true and real because of media revelations of fake news that spiked during the 2016 US presidential election (Carson 20171).

Recently, fake news has been intended to characterize and deliberately misinform, referring to fabricated information that closely mimics news and taps into existing public beliefs to influence behaviour (Waisbord, 2018). Fake news is a challenge for journalism pedagogy because it creates a “fight” for establishing credibility, truth and perception for students, in the community.

The challenge here are the transformations of the public perception lead by the digital proliferation of misinformation and contested truths. They are part of today’s dynamics, multilayered, chaotic public communication. These issues are particularly relevant to the everyday lives of new generations, especially if we take into account the growing use of social media platforms for leisure purposes rather than online news consumption. Recent studies have documented that Z generation - born between 1990 and 2010, in the era of the advent of the Internet and new technologies - live their everyday experiences in permanent connection with these platforms and the contents they make available, and that there is a direct implication in their personal, social and professional lives (Silveira & Amaral, 2018). And as far as news consumption is concerned, there are already several studies that reveal the trend towards online information consumption by younger audiences, compared to access to news via conventional media (Silveira & Amaral, 2018). An almost exclusive consumption of online news can be revealing of some skepticism and disbelief towards the media and information, as well as a motivating element of the generalization of the idea of fake news, and may even result in little interest to follow current events (idem).

In this complex context, young people are surrounded by technology and digital platforms, creating their perceptions of the world and reality. Therefore, it becomes important to understand, in a deeper way, the relationship that these publics have with the news and digital platforms, as this is a means to access current events consumption that can lead to the proliferation of fake news. In order to contribute to the increase of knowledge about this problem, which, especially in the Portuguese academic context, still shows little robustness, this research emphasizes the need to understand the news consumption practices by the new generations and the perceptions that they create about the idea of fake news, focusing on the media and digital literacy skills and on how these relate to the interpretations and dynamics of consumption.

Understanding fake news and the need for media literacy

Fake news today seems to be intrusive and diverse in topics, styles and platform uses (Shu et al., 2017). It is hard to find a generally accepted definition for fake news. Stanford University provides the definition of fake news as “the news articles that are intentionally and verifiably false, and could mislead readers”. Cambridge Dictionary (2018)2 defines fake news as being “false stories that appear to be news, spread on the Internet or using other media, usually created to influence political views or as a joke”. Also, the Collins Dictionary (2018)3 refers to it as being “false, often sensational, information disseminated under the guise of news reporting”.

Fake news is all about content that is produced as false, focused on targeting confused readers (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017). These authors talk about why there is a need to create fake news. These needs are ideological and economic in nature, since it generates a sense of confusion that allows the possibility to inflect political damage and possibly profit from the misinformation that was produced (ideological). Also, by benefiting the fake news creator which can profit directly or indirectely from the publication of wrong data (economic) (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017).

Garcia (2016, pp. 65-66) has determined that there are three key pieces in fake news that appear to entrap the users with misinformation. Those are the following: (i) a stunning headline; (ii) a revelation that reaffirms us or that make us feel outraged; and (iii) a legitimate and reliable appearance.

Fake news is a consequence of a communicative ecosystem that has serious weaknesses and risks and the result of malice and intentional deceit. Kucharski (2016) stated that the dissemination of fake news is similar to a virus epidemic. The range of contagion and reproduction is alarming. Highlighting this phenomenon is the lack of verification systems and procedures to validate news. In this environment, fake news adapts to dissemination, when the system is unregulared.

A person may unwillingly share fake news, and the message that is being spread is ultimately based on false information. Therefore, the content based on that information is ungrounded and biased as it is notempirically true, although it might be shared as such. According to Palczewski, Ice, and Fritch (2016, p. 145) this can be a complication because telling events as known through their subjective experience, is not telling an empirical truth.

The term fake news is used to cover a wide spectrum of sources, “hoax-based stories that perpetuate hearsay, rumors and misinformation” (Mihailidis & Viotty, 2017, p. 4). There are fake news sites that write and distribute content in order to drive traffic to websites and earn income from the clicks and the ads (Sydell, 2017)4. Unfortunately, many readers believe the false claims and share the information and it happens to go viral. The consumption of fake news can, for example, impact voting and legislative decisions (Sydell, 2017).

Instead of labeling each source as real or fake, it would be considered more productive in the way of combating the use and sharing of unreliable content effective, focusing on where the information itself comes from, who is actually producing it and for what purpose.

With the intense development of the Internet, we have watched a very rapid growth in the distribution of fake news through social networks and word-of-mouth. There is a considerable amount of information available, so finding a reliable source is a complex and challenging task for any particular information consumer, but especially for younger ones. Young people are intriguing and have been descrived as “digital natives in a land of digital immigrants” (Rainie et al., 2017). However, they may be lacking in tools and critical ability to correctly evaluate information, particularly because they are not yet fully developed intelectually and emotionally, and do not have much life experience as compared to adults (Flanagin & Metzger, 2008).

Research demonstrates that younger people often approach online information suboptimally (Kafai & Bates, 1997; Livingstone et al., 2005; Shenton & Dixon, 2003; Walraven et al., 2010). According to Miriam

Flanagin et al. (2000), studies have shown that young people are uncritical or reliant on inappropriate criteria when it comes to searching for online information. In a study by Shenton and Dixon (2003), they asked the participants to describe their experience when searching for information for school or personal use. Of the 188 students that were interviewed, none said they did anything to verify the accuracy of the information they found. The authors (idem, p. 1041) concluded that most of the time young people “do not even realize the need for such scrutiny”.

Adults are more willing to trust a particular website if they can positively link it to its perceived quality (McKnight et al., 2004). This suggests that adults who have a high propensity to trust others might be more inclined to believe information they find online, than individuals who are more distrustful of others. Therefore, we have to consider a variery of perspectives when covering the process of news literacy, covering all parties that have a stake in how citizens engage with the news.

Millenials are contesting the very notion of “news”, because what is considered news today is very different from what we could expect and it remains to be seen how these concepts of news will evolve with time.

Young people believe that if the information is relevant they will know about it, this is the perfect mindset for contextual understanding of how news are made and disseminated (Ashley, 2016).

Although fake news is not a new problem, people are receiving more information and its importance has increased in their everyday lives. We have seen a rapid consumption of online news by the younger generations, often via social media. Technology makes it easier for fake news publishers to create advertisements and false information that is deceiving; information that seems like it comes from a reputable source. Nowadays, news consumers of all ages are having a hard time understanding the information they receive and making sense of what is real from what is fake. While digital natives might have a better time accessing content, they will need guidance in understanding what to do with the information that comes across their social media feeds (Auberry, 2018).

Social media uses and news consumption by youth

Recent researches into the use of media and news consumption by young adults document the importance that digital platforms and the online world acquire in the everyday life of this generation, as a source for entertainment and as a means to keep abreast the events of society and the world (Amaral et al., 2019). Particularly in developed societies, access to the internet and digital platforms is a reality: for example, in Portugal, PORDATA data from 2018 shows that more than 3 million individuals subscribe to the internet, and in 1997, only 88,670 Portuguese had access to this service. In the national context, a report by Ponte et al. (2014) states that access to new media increased in recent years, specially in a domestic context, because of online media practices among young people for entertainment purposes (being on social networks, playing games, listening to music). These results can be extended to other European countries, such as Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Spain and Romania (Mascheroni & Cuman, 2014).

The presence of digital tools in everyday life has implications for the reformulation of behavior, both on a personal and social level. In a study by Amaral et al. (2017), that aimed to describe indicators of online activities of 1824 Portuguese children and young people with the objective of analyzing their digital media practices and network consumption, the authors concluded that the daily life of these users is marked by an intense online involvement, with a youth culture built around digital platforms. The authors found that almost 90% of young people access the Internet on a daily basis, mainly through a laptop and mobile phone. In the collective context of socialization, mostly done online, the practices are mainly of a playful character (emphasis is given to listening to music online, watching videos online and participating in social networks). In fact, an interesting result attests to the fact that there is a “hierarchy for digital practices”, which allows young people to work together (Amaral et al., 2017, pp. 127-128).

In general terms, the understanding of these uses as regards children and young people is consistent in the national and international academic scene (Amaral et al., 2017; Mascheroni & Cuman, 2014; Silveira & Amaral, 2018). Despite this, it is necessary to know and analyze, in a deeper way, the online practices of young people entering adulthood and the way digital platforms are used as tools for access to information and for the development of civic and political thinking. In a recent qualitative research carried out in a national context about media and news consumption by young people, Silveira & Amaral (2018) note that social networks, with particular emphasis on Facebook, are manifested as privileged means for these users to access information. However, experts draw attention to the fact that, although such means may by their nature provide interactive possibilities, content sharing and commentary do not prove to be usual practices in the use of the network for the purposes of current events consumption. Another result is that young people associate, in a non-judgmental way, certain sensationalist news content with the idea of fake news, revealing high levels of skepticism about the information content.

In a recent study by the Digital News Report (2018), commissioned by Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford at YouGov, more than 74,000 respondents from 37 countries were involved in order to understand and analyze their ways of news consumption in digital media. Including young adults in the sample (representative of the Portuguese population), the results of this quantitative research, for the Portuguese case, reveal intense information consumption in social networks, especially Facebook, but at the same time, a permanent contact with content that is classified as fake news (Cardoso et al., 2018).

Study on fake news reception by university students studying in portugal

Methodology

Based on the assumptions that were presented, we intend, with this investigation, to understand, from the perspective of young adults, the nature of the interactions and appropriations they establish with the news, with particular emphasis on fake news. In this sense, the primary objective of this research is to understand and analyse media and news consumption practices within university students, studying in Portugal, in the Faculty of Design, Technology and Communication (IADE - European University of Lisbon). We intend to define these audiences’ preference profiles, identify practices, analyse their relationship with the media and find patterns in their use of technology to access information. From their perspective, we intend to understand and analyse the following specific objectives: i) their habits of access and news consumption in social media platforms; ii) their perceptions of news concept and specially regarding the idea of fake news; and iv) if they can distinguish between fake news and news by analysing their perception of it.

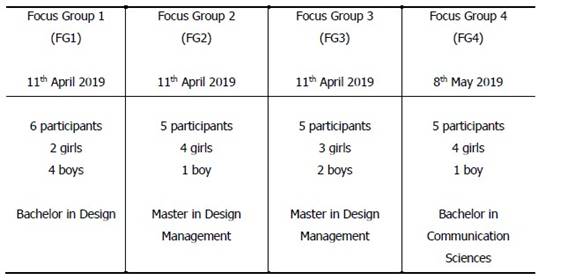

The method chosen for data collection was qualitative, operacionalized through the development of focus groups (FG). As a result, four mixed focus groups were developed, since the goal was to create dynamic sessions, to make it possible to confront opinions between participants, and gauge trends in their choices and discourses. The groups were composed of 21 participants studying in IADE, and were developed in 11th April and 8th May 2019. The sample is of convenience, not being representative of the population.

Following a script developed from a set of guiding questions articulated with the previously presented research objectives, the groups analysed and discussed about the news and the conventional and new media platforms through which they follow these contents.

Data collecting of the activities was achieved using an audio recorder. The sessions were transcribed in full. After the transcription, we made an initial global reading of the sessions and the field notes, with the aim of entering the discourses, and observe general trends that emerged from the participants’ discourses that could be useful for framing the questions and objectives underpinning the sessions. After this first reading, the data was analysed using NVivo and coded according to the specific objectives outlined for the research presented at the beginning of this section. The analytic procedure sought to emphasise the importance of the participants’ discourses, while bearing in mind their style of expression. We organized the data collected and analysed it according to units designed from the guiding objectives of the research, identifying trends for the purpose of providing understanding and structuring answers about the phenomenon under study. Support for the main categories that emerged from the data were habits of access and consumption of the news by the participants, especially through the use of social media platforms; their perceptions on fake news; and their critical skills regarding the news in general and fake news in particular.

ParticipantsTabela 1

The sample consisted of 21 university students in the academic year 2018/2019 of which 13 were females and 8 were males. Respondents were between 21 and 26 years old. The average age is 25 years. Three students were Brazilians (Humberto, Bettina and Giovanna); one from Angola and the rest of the sample was Portuguese. All of the participants live in the Lisbon district. Most of the participants work as they study and in the areas of Design and Communication. All of them have access to the Internet, follow news and have access to it every day through a smartphone or a portable computer. They mostly have social media accounts on Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn. Students follow news information mostly on the Internet, through Facebook, Instagram and news platforms. All of the students are familiar with the term “fake news”.

Results

The data presented is articulated and organised on the basis of the objectives and the results obtained.

Access and News Consumption through Social Media

The participant’s statements during the focus groups allowed us to conclude that they keep up with current events as part of their daily routine, being an activity that they enjoy and is of interest because they look for the topics represented in the news. The role of social media, in particularly, social networks, is very relevant, particularly Facebook.

An interesting result comes from the statements of some of the participants (Inês and Beatriz, from FG3) that refer Instagram, as well as Facebook and Twitter - which are mainly young people’s social networks used to access information (Silveira & Amaral, 2018), as a source of news, using tools such as Instastories to spread that content of information.

Inês: Sometimes I follow the news on Instagram accounts that are dedicated to this. Beatriz: I follow more [news] through the feed of social networks ... Facebook, Instagram. But it's more on Instragram. The rest I listen around and look for what interests me the most. But usually the news reaches me through the feeds. M (moderator): But what means of information to you follow on Instagram? Beatriz: The normal ones. There are many newspapers that are also on Instagram. There are headlines and links to learn more. Inês: Usually it's in the stories. We follow the account on Instagram, the news appears in the Instastories and then slides up in pop-up. [FG3]

In the context of Instagram and Twitter, it is important not only to affirm these platforms as a way for the students to follow the usual information channels of relevance and general knowledge of the public in the national context (they referred the national pages of Público and Expresso), but also the fact that it becomes a way to consume news in alternative formats allowing access to content that matches their preferences.

Margarida: One of the pages I follow on Instagram is ATTN. M: What is it about? Margarida: It’s about current events. It talks about controversial issues. It’s American. It interests me more because it talks about the issues that I like. [FG3]

Although social media presents itself as a privileged means for the consumption of news, especially because of its portability which allows access to content at any time and place, television and print newspapers continue to be present in the daily life of students, while information source; an aspect already demonstrated in other studies on the same theme (Alon-Tirosh & Lemish, 2014; Silveira, 2019; Silveira & Amaral, 2018).

In the various groups, news are associated with values such as the contribution to information and knowledge, being, in the opinion of Beatriz and Bettina (both participants in FG2), as one of the vectors of citizens' lives that effectively contributes to their knowledge of the world and the development of representations about reality. Along with family, school and friends, the media thus assume an influential role of socializing agents, contributing to the apprehension, assimilation and interpretation of issues of life and everyday living.

Beatriz - I think there are a lot of things that influence [our world knowledge]. I think it has to do with our life experiences. The media has a say in that. What we see and read influences us. Whether it’s in the books or in the media. In our families, school, and the place we grew up in. Bettina - I think I don’t even think about this. Family, and the media, all of that influences us without us even realizing it. [FG2]

Although digital media has a very present role in the news, the fact that they are, by their nature, formats that enable forms of online participation that go beyond simple access to information, does not seem to be something that integrates these consumptions, especially with regard to commentary on the news. This may be related to the fact that young people do not give credibility to the general comments made to online news by users, considering that the fact that they express their ideas about certain information may also be a factor of de-sensitization of their own opinions, once they "mingle" with those such views for which they show skepticism. In turn, the sharing of news is more visible, especially when it comes to matters that integrate their interests and to which they associate truthfulness.

M - Do you comment or share information? Filipa - I don’t normally, no. The comments on the Internet don’t really add anything. People go there only to say bad things, it’s nonsense. Sometimes there’s news with hundreds of comments, and only one or two say interesting factual things. The rest is just not worth reading. Catarina- I rarely comment. Since most people do not say things that matter, I will not write my views either. It doesn’y make sense for me to do so. Rafael - I usually share on Twitter, but only when there are topics that interest me and when I realize that they are really serious matters, even true ones, like Human Rights, Women's Rights ...! [FG4]

Perceptions and Conceptualization of Fake News

The notion of fake news is known to all participants in the groups, and there is convergence in the association of this concept with the evolution and proliferation of the digital media platforms. The participants' testimonies show that the democratization of Internet access and the multiplication of online news channels are, in their opinion, the main factors of origin and proliferation of fake news, as we can see from the following statements: "Yes, fake news are related to the online world "(Bettina, FG2); "Nowadays, it is very easy to write things on the Internet, anyone can make up news" (Margarida, FG2); "For example, I do not trust Sapo.pt. I do not know why, but I always associate it with propaganda or something less serious "(Bettina, FG2).

When discussing fake news, participants suggest words such as "manipulation" (Sara, FG1), "distortion" (Yeto, FG1), "misinformation "(Vasco, FG1), and "sensationalism" (Beatriz, FG3). Thus there is an approach to ideas that diverge from the principles and foundations of journalism, like informing or searching for the truth of facts.

The statements converge in the sense of considering that fake news are discrediting journalism and feeding distrust in journalists and the media, in general, however Margarida (FG2) suggests that there is danger in generalizations, showing that not all media are spreading fake news, and most work in favour of the truth and information.

Margarida: We need to calm down a little. Not all media shows fake news. There are a few that do it, others don’t. There are still journalists who search for the truth, that don’t believe in things at first glance. [FG2]

In this context, according to statements by two participants (Margarida and Beatriz, from FG2), there is a significant association between the national general public service media, of which RTP stands out, and the national thematic channels dedicated to information production, like SIC Notícias and TVI24, to which values such as trust, credibility and deepening of the news are associated, showing a marked divergence compared to the distrust generated by other organs (such as Correio da Manhã), sensationalist and more dedicated to entertainment content.

Margarida: RTP doesn’t have that many entertainment shows, that’s why I might associate it to something more serious. And because it is the oldest one. And because it has a lot of debate shows and less entertainment, maybe that is why I associate it to something more serious. M: Which media do you consider more credible? Beatriz: RTP1, SIC Notícias, TVI24… Because they only work with news, they end up focusing on that more and having more time to investigate it. [FG2]

According to the generality of the testimonies, the source of the information proves to be of crucial importance in the evaluation of the news and in the detection of contents that do not correspond to the truth. Participants, particularly those in FG4, point out that the source is one of the most significant indicators of trust, or lack thereof, in the content transmitted.

Rafael: I always have to see where the news comes from. Filipa: The source is very important. Catarina: The source is the most important. Filipa: For example, if you say the source is Lusa [Portuguese news agency], I believe it. Now, if it's a website I've never heard of, a foreign one, you doubt it. [FG4]

In their testimonies, participants reveal that there are current topics that are more likely to target fake news than others. Politics-related topics are common references in all focus groups.

Media and News Literacy Skills

Although the participants of these groups recognize that media constitutes the main source of fake news that uses privileged channels, reaching these contents in a wide audience, their testimonies also show the role that other media platforms (with emphasis on WhatsApp) have assumed in the propagation of fake news, allowing other actors to position themselves as producers of this type of messages, creating networks of sharing and commentary that enable the propagation of information. This aspect was particularly relevant in the context of the last Brazilian presidential elections, according to Bettina (FG2). In her statements, these alternative ways of propagating ideas were consolidating speculations and rumors that ended by "feeding" other channels and giving rise to fake news that, given the dimension reached, were added in official channels, reaching the public on a large scale.

Bettina - In Brazil, on our last elections WhatsApp was a means to reproduce fake news very quickly, without any validation. I’m talking about groups and people to people. In this case, I’m talking about normal people who share and create false information and distribute it. There are people saying that who produced the campaign is who is spreading those news. [FG2]

Although participants believe that the media and digital platforms can play a leading role in the issuing and dissemination of fake news, there are statements, such as those shown below, that transfer some of this responsibility to audiences, assuming that media illiteracy may be one of the contributing factors to this same spread.

Humberto: I think that those who believe in fake news have poor knowledge of the context, and have no interest in searching for or comparing other sources of information. It is a lack of education and access, and of interest. When the elections were in Brazil, the worst news was transmitted not by the media, but disseminated by people. Therefore, people also have to question and seek. [FG2]

Sara: Usually we can never be sure [that the news is true or false], that's a fact, we were not there, we do not know, we'll never be 100% sure, being that to perceive or distinguish in any way if it exists, or whether it's a fake news or not, we have to compare with various channels of communication - If all the channels, or most of the information channels, have the same perspective or the same view, then yes, we can believe it. But I guess most people do not do this. They believe in everything and this [fake news] never ends. [FG1]

M: So the news, confuses you, is that it? Beatriz: Yes Inês: I think they are a starting point for us, from our own initiative, to really look for what happened, from various sources. Inês: Because a single source is no longer enough. Margarida: We have to be our own detectives, really. You can’t necessarily believe the first [news]. [FG3]

Despite the widespread of disbelief in the information disseminated by the media, specially new platforms and critical skills of citizens in relation to the news, the following testimonies stand out, revealing the involvement of these young people with the current events and news literacy levels that make it possible to mobilize analytical and critical thinking skills.

Margarida: For me, news I consider true is when I see it in the official media ... but even so, I make a comparison. Nowadays there is much ease of writing things on the Internet.

Humberto: When the news is identified, you know how to filter and compare. When the page is not identified, you should not follow. For example, when it is fake news and about politics, we already know that it is subjective and directed opinion.

Beatriz: I remember the Donald Trump elections. There was always political interest behind. You can see from who writes and publishes ... the links. We can tell if it is fake news or not. I guess it's not that complicated to detect if it's fake news because it's trending. [FG2]

M: How do you identify a news story as false? Matilde: For the content.

Filipa: I think it's for several things: for example, sometimes the title gives you a quick glance. So if it's too implausible.

Ana Catarina: When it is too exaggerated. Filipa: By the place where it was published. [FG4]

It is of particular relevance to make reference, as far as the media literacy competencies of the new generations are concerned, to the statements of the students of Communication Sciences (FG4). They understand that the knowledge acquired in the academic course actively contributes to their being more competent and critical in their assessment of the media and the news, considering that, compared to young people who do not attend courses of this nature and don’t have such higher levels of literacy for the news.

Catarina: I think everyone agrees that we are now much more apt to know what fake news is.

Matilde: And even comparing the five of us, so to speak, with most of our friends who are not in this course or have nothing to do with Communication, they believe fake news more easily than we do.

Rafael: But it's also because we are constantly talking about it, and we learn about it. Therefore, we are more attentive. [FG4]

In spite of this recognition, we emphasize that in the overall computation of the statements from the participants in all focus groups, the value of being a Communication Sciences student regarding the manifestation of critical competences did not emerge significantly in comparison to the other participants’ focus groups.

Discussion and main conclusions

With this research, we intended to understand and analyze the dynamics of reception of university students, studying in Portugal, with fake news, based on their perceptions and interactions with the current events consumption through social media. Although the results obtained cannot be extrapolated to the totality of university students studying in Portugal, they allow us to conclude that the news follow-up is an integrated practice in the daily life of the younger generations, as confirmed in other national and international studies (Alon-Tirosh & Lemish, 2014; Silveira, 2019; Silveira & Amaral, 2018). Along with other social networks, Instagram is also a means by which the younger ones follow the news; an enigmatic aspect that has not been reported with robustness in other studies within the same problematic, which mainly address the relevance of Facebook and Twitter (Silveira & Amaral, 2018).

Nonetheless, it is important to emphasize the permanence of conventional media, especially television, as a respected and credible media for these audiences; an aspect already demonstrated in other researches about the same theme (Park et al., 2018).

Despite the importance of television, and in line with what has been corroborated in other studies (Cardoso et al., 2018; Park et al., 2018), young people are looking for alternative formats of information consumption that are not restricted to national information channels, but meet their tastes and preferences, showing eclectic news consumption both in terms of format and content.

In conclusion, generally participants indicate a decrease in media consumption due to the proliferation of fake news, which in their opinion originates from the online and the permanent need to create content. This results in not deepening the news to seek the truth of the facts. There is an understanding of the positioning of the new actors that emit fake news, like in WhatsApp, which gives rise to new literacy skills mediation by publics and users, in order to learn to critically evaluate not only the content that gets from them, but also the credibility and interests behind those sources. At the same time, the lack of media literacy among the general public was another of the highlighted factors, as an element that may legitimize the propagation of fake news, although the participants denote, in relation to themselves, levels of understanding and skills that enable them to evaluate the news and position themselves as critics of the spread of fake news.

In line with other studies, as these new generations grow and mature, they become more sophisticated media receivers and more apt to evaluate the messages and contents that arrive to them through multiple platforms (Metzger et al., 2015). Nevertheless, despite some skepticism, it should be noted that the Portuguese public is among those who, in the context of the European Union, and together with Finland, are more confident in the news, although in a decreasing trend (Cardoso et al., 2018). This aspect may be related to the low political polarization of the Portuguese citizens and the positive perception that exists around the journalistic practice (idem).

At the confluence of these results, we may say that there is a need to reinforce strategies that enable citizens to develop skills that allow them to be more critical of their own vision of the world and, at the same time, of the world that comes to them and is portrayed in the media. Media literacy is important and most participants agree that the older generation has a hard time identifying between fake news and the truth. Building on the distrust of fake news, they can start confronting sources of information and question the news they receive through alternative platforms. This may constitute an important step towards a more conscious worldview and the development of civic-political values.