1. Muristan research project

For several years now, an interdisciplinary research project has been investigating the Muristan in Jerusalem. The present article aims to give an insight into the work with a few examples and to present results in brief. It deals with the early phase of the Order of St. John, whose origins in Jerusalem date back to the time before 1099 and which, during the period of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099-1187), developed into one of the great military religious orders and became the Order of Hospitallers. The beginnings of the order can be traced to an area south of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Numerous pilgrims' reports and medieval sources clearly describe the famous hospital, which formed the core of the Order's seat, at this location. Most of these sources have a long scholarly tradition, and the functioning of the hospital is well known through the statutes of the Grand Masters and reports from patients admitted there. All the more striking, however, is the fact that the still existing building remains are hardly known today. As a result, there are still central questions which cannot yet be answered: Which buildings actually belonged to the Order of Saint John? What was the relationship to the two Benedictine monasteries, which were located on the same site as a male and female institution? How were the functions of the Order's headquarters and the hospital distributed among the individual buildings?

Compared to historical research on the origin of the Order of St. John1, field research has always lagged behind in terms of archaeology, building archaeology, and art history, even though there is already a considerable amount of foundational research2. The aim of our project is, therefore, less oriented towards the history of the Order, and more towards the history, architecture and development of a central area in the heart of the holy city. With this in mind, the project seeks to answer the following questions: What did the site look like before the establishment of the Order of Saint John? In ancient times, it is generally assumed that the forum of the Roman-Byzantine city Aelia Capitolina was located here. What happened here in the 11th and 12th centuries, and how were the buildings used, abandoned or modified after 1187? Numerous questions follow here.

Some years ago, a team was formed to deal with these questions and to examine the area of the Muristan in its development from antiquity to the 19th century from an archaeological and architectural point of view3. The focus of the project is on the re-evaluation of previous excavations and the investigation of the existing building remains, developing a catalogue of the building sculpture to be assigned to the Muristan, and the compilation and re-evaluation of all archival, historical, drawing and photographic sources4. New excavations are not possible within the framework of the project, but building surveys of the medieval building remains will be carried out as far as possible5. Based on the existing plans, a computer-aided 3D model of various time periods was also created6. The aim of the project is to compile and reassess all available materials, also as a basis for further research. The work is largely completed, and the first interim results have been published7. The final publication of the project is in preparation. In this article, some selected observations on the medieval building remains are being presented, regarding the reliability of Conrad Schick's plans, some results of our recent investigations of the preserved architecture and the identification of buildings and functions within the area.

2. Conrad Schick and his General Plan of the Muristan

The most important sources for the investigation of the building remains are plan drawings made in the last third of the 19th and at the beginning of the 20th century. Until then, the inner area of the quarter was completely covered with rubble and earth. (Fig. 1) On the periphery there were shops and workshops along David Street, the Suq Streets and the Christian Quarter Road. The monastery of Santa Maria Latina was in ruins, the vaults had largely collapsed, and it had not been inhabited for a long time. The church of Santa Maria Maior, whose existence was known from archival sources, had completely disappeared. Only the church of St. John remained in function as a church over all centuries8.

From the middle of the 19th century, interest in the holy places of Christianity grew, and the young discipline of archaeology made its way to Jerusalem. European powers secured pieces of the Holy City, among them the King of Prussia, who in 1869 acquired the eastern part of the site identified as St. John's Hospital or Muristan, while the rest of the area was in the hands of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate. The initial sondages and excavations brought to light a huge field of ruins, which could be excavated with relative leisure in the eastern part; the remaining western part, however, was largely covered by a bazaar and commercial area during the years between 1898 and 1904 without investigation.

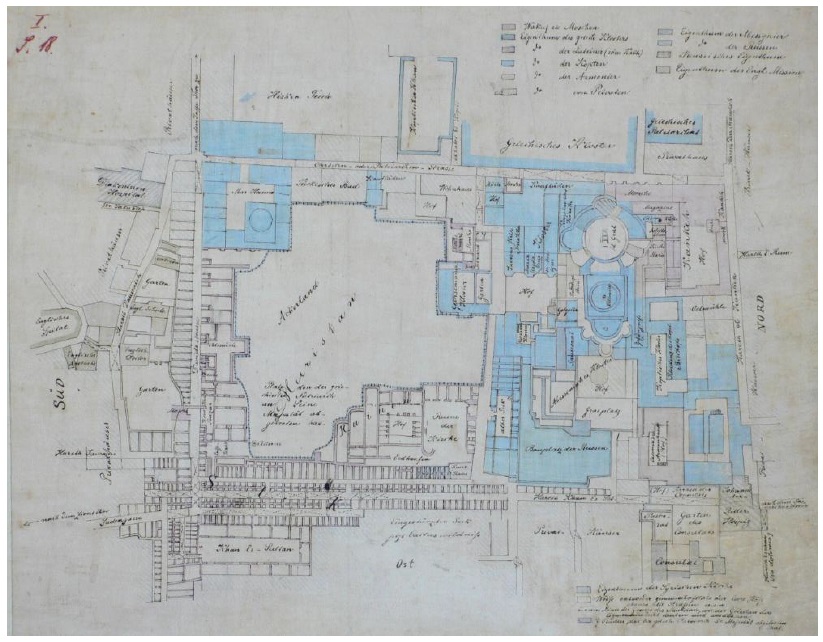

Fig. 1 Plan of the Muristan and the adjoining Church of the Holy Sepulchre, drawn ca. 1869/70 to mark the properties of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate and the Prussian Crown (north is on the right); drawing by Conrad Schick, from the files of Friedrich Adler (Source: Berlin, Evangelisches Zentralarchiv EZA 56/501; approved for publication on 09.06.2020).

Conrad Schick (1822-1901), a German missionary trained as a precision mechanic who had come to Jerusalem in 1846 and remained here until his death, worked as an architect, archaeologist and draftsman. He observed the building activity in the Muristan, was responsible for the documentation and excavation in the Prussian part, and made numerous plans of the building remains in the Muristan. As valuable as his drawings are for us today, they are unfortunately not completely reliable in all areas. But until today, his drawings could only be verified by a few small-scale investigations.

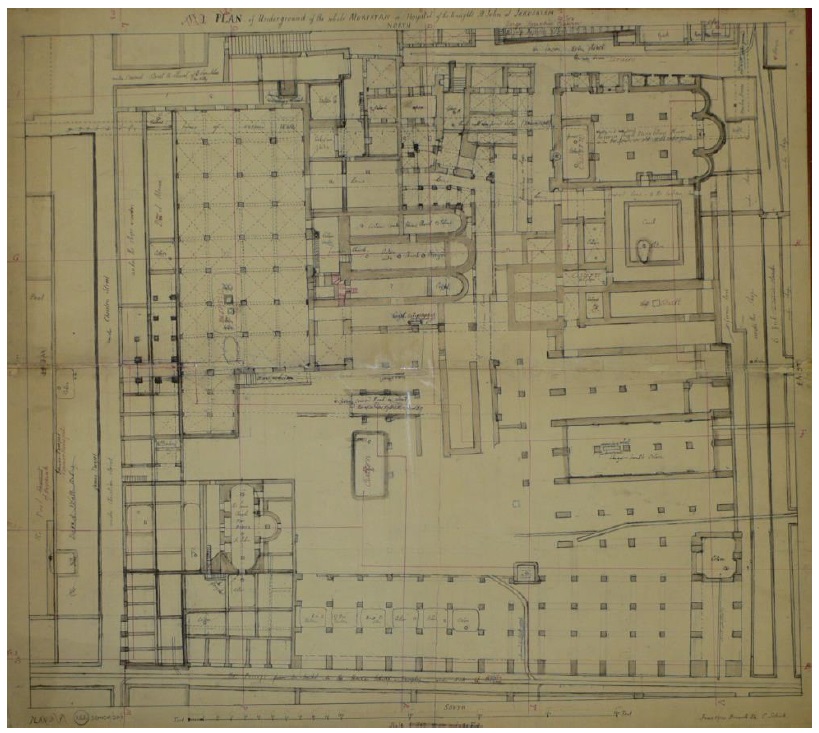

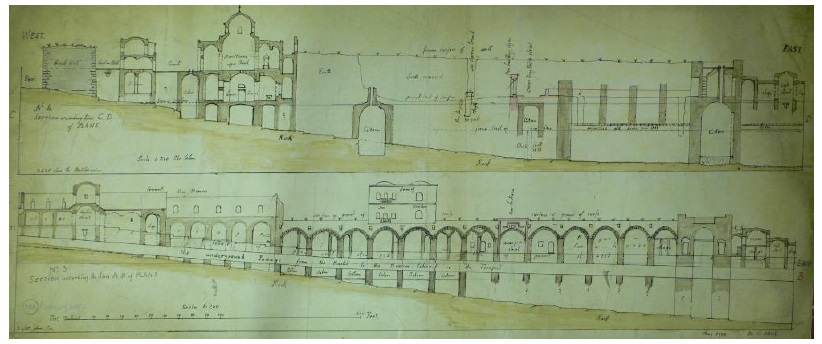

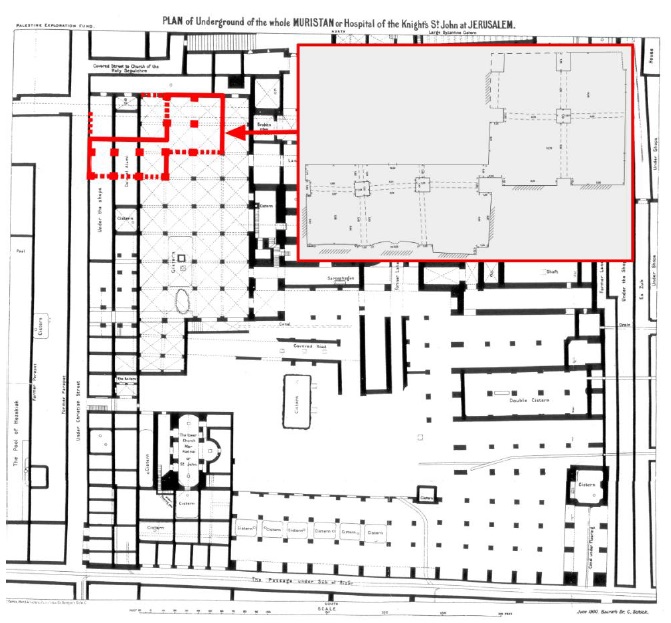

In 1900, following the clearing and rebuilding of the Prussian and Greek parts of the Muristan, Schick prepared a general plan of the entire area on the basis of his observations collected up to that time. It consists of floor plans in two heights and ten section drawings and is now kept in the archive of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (Figs. 2,3) Of this series of plans, only one - greatly simplified - ground plan was published in 19029.

Fig. 2 Plan of the Muristan: ground plan on lower level; Conrad Schick 1900 (London, Palestine Exploration Fund, Schick 201/01. Courtesy of the Palestine Exploration Fund; approved for publication on 04.06.2020).

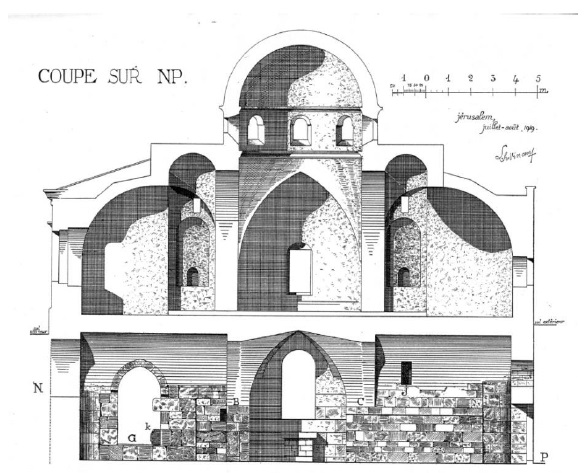

Fig. 3 Cross section through the Muristan; Conrad Schick 1900 (London, Palestine Exploration Fund, Schick 202/02. Courtesy of the Palestine Exploration Fund; approved for publication on 04.06.2020).

However, an analysis of this set of plans, which appears so consistent, shows that its presentations are based on very different levels of knowledge and are of varying quality. This can be seen in places where Schick himself was able to carry out investigations over many years and drew up several plans, some of which differ considerably from one another, for example in the area west of the abbey church of Santa Maria Latina (today the Protestant Church of the Redeemer). However, because the building remains today are no longer preserved or only survive in small remnants, an assessment of how the structures actually looked can only be made by taking into account other contexts.

Although the plan published in 1902, i.e. the simplified general plan, is not exact in various areas, it has nevertheless repeatedly served as a source for further research and as a basis for mapping for over 100 years. This plan has been used to mark halls that are said to have served as hospital, in addition to marking paths mentioned in documents of the 12th century10. To what extent this is compatible with the actual findings has not always been sufficiently taken into account.

A better documentation of the remaining architecture is essential. It is important to note here that by no means have all medieval buildings on the site disappeared, but that there are still considerable remnants of original building fabric. An important goal of the Muristan research project is, therefore, the documentation of these building remains as far as possible today.

3. Results of building archaeology in the Muristan area

A detailed examination of the building fabric allows important observations to be made, even if only a rather small part of the medieval buildings in the Muristan are still preserved today. On the basis of observations on building techniques and architectural forms, it can be concluded that the entire building complex did not develop in one building campaign, but successively and in different construction techniques. Furthermore, individual components can be combined to identify buildings and functional units. Decisive factors here are, in particular, the type of masonry, the size and working quality of the stones used, the respective stone and mortar materials, the type of surface treatment of the blocks and the presence and nature of stonemasonry marks. Characteristic also is the respective construction method, such as how vaults and arches are made, and whether or not there are piers and buttresses. Essential are ground and elevation forms, axes and alignments, differentiation of exterior and interior walls, design and construction of doors, windows, stylistic elements such as capitals, building sculpture etc.

Based on a variety of features such as the kind of masonry, stone material and working, stylistic elements, building sculpture as well as mason's marks it can be determined, for example, that the rebuilding of the Church of St. John or the construction of the Church of Santa Maria Latina with the convent buildings adjoining to the south belonged to an earlier period within the crusader architecture (Fig. 4-6), while the halls located in the southeast of the area, the Church of Santa Maria Maior and the adjoining buildings to the north represented a more recent development within the quarter (Fig. 7).

Characteristic for the large hall buildings in Muristan, specifically, is a modular design consisting of piers and vault architecture above transverse arches, into which internal walls could be inserted flexibly and as required. Nevertheless, original partition walls usually integrate into piers and outer walls. Deep wall piers, e.g. in the range of the facades along David Street, are particularly characteristic on the outside of buildings, forming an abutment in the form of buttresses. Inside the courtyard, e.g. on the inner façade of the south-eastern hall, such deep wall piers probably served as supports for flights of stairs and galleries on the upper floor, similar to what is preserved in the area of the Hospitallers in Acre and other crusader castles11.

Fig. 4 Cloister of S. Maria Latina (today Church of the Redeemer), ground floor of the north wing (photo: Dorothee Heinzelmann, 2018).

Fig. 5 Cloister of S. Maria Latina (today Church of the Redeemer), capital, ground floor of the east wing (photo: Dorothee Heinzelmann, 2019).

Fig. 6 Cloister of S. Maria Latina (today Church of the Redeemer), example of surface treatment of stone blocks (photo: Dorothee Heinzelmann, 2019).

4. The central Convent and the hospital: spatial distribution of functions

Within the Muristan, according to the historical sources, there were two different and very specific units, namely the headquarters of the order and the hospice or hospital area.

The Order's headquarters, comparable to that of the Knights Templar on the Temple Mount, took over an increasing number of central functions of the young Order, although these were not always precisely named in the sources. Conclusions can be drawn from the statutes of the Order,12 which, however, always record a state of affairs that had often developed many years earlier13. The individual court officials are named very early on in the documents. They allow us to estimate the size and importance of the central Convent. With Senechal (since 1141), Constable (since 1126), Marshal (since 1165), Butler (since 1141), Chamberlain or Treasurer (since 1135) and Chancellor (since 1126), the Knights of St John had the same court officials as the Templars, but also as the Patriarch or the King of Jerusalem14. Even though the other courts are not known architecturally or archaeologically, the mere fact that the central convent was on a par with the royal or patriarchal palace as far as the court offices are concerned suggests a prominent architecture. It is possible that the expansion of the convent took place roughly parallel to the increase of the court offices, i.e. in the middle of the 12th century.

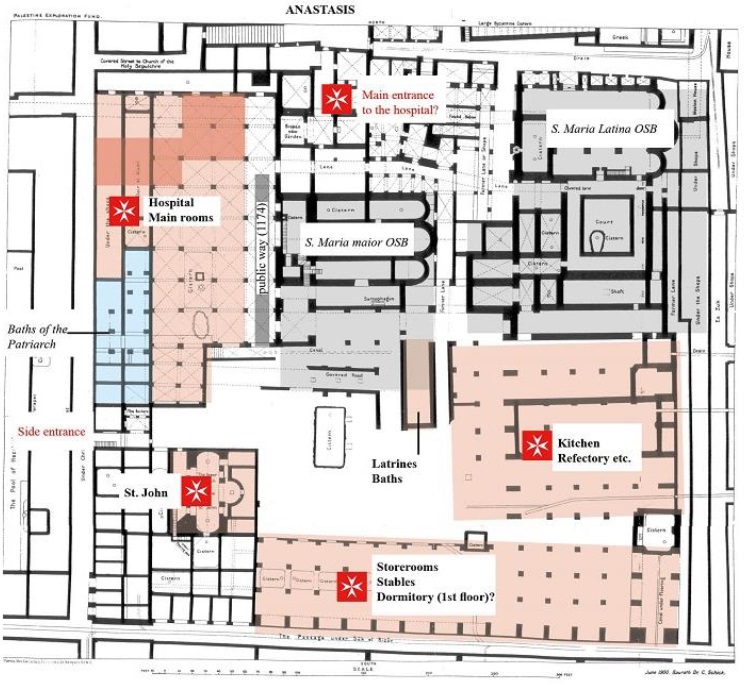

A similar process can be observed in the field of the hospital, which developed from a pilgrims' hospice at the beginning of the 12th century to a modern hospital for medical care. This function can be seen at the latest around 1170/80; it required a large number of different facilities. In the written sources, numerous functions of the hospital are listed, and the daily routine is described in a very detailed manner15. We read about infirmaries, a clothing store, a church and an altar, a kitchen area, toilets, storerooms and stables. So far, none of these functions could be located with certainty in a specific building or area within the Muristan16. A re-evaluation of the archival documents and the pilgrim's reports in relation to the building remains leads to the following picture: The main access to the hospital was in the north, opposite the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. A side entrance led into the quarter from the west, from the Patriarchs' Street. The original hospital wing, which housed the hospital rooms, is supposed to have been located to the west. However, since there were a large number of units within the hospital, it is possible that the wards were expanded over time and the hospital function extended to various buildings.

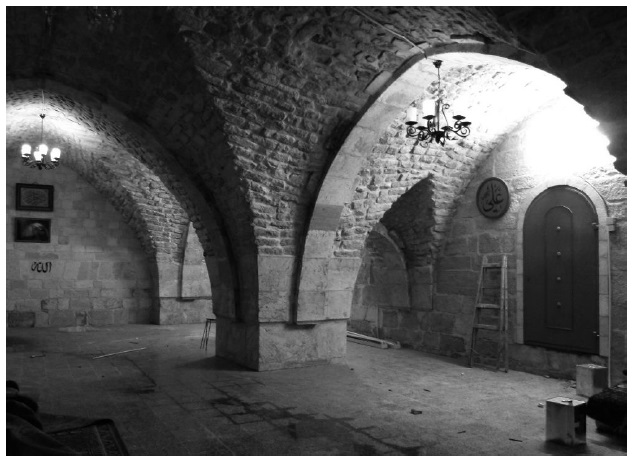

To the west there was a building with piers and vaults in several aisles and at least two storeys high, but it was obviously different from what Conrad Schick presented in his general plan. In total, it consisted of five aisles in the northern part and probably extended to the Christian Quarter Road in the west. This could only recently be found out after the Omar Mosque was enlarged and further medieval vaults became visible, which had previously been filled with earth and were not accessible. This finding, however, shows in an exemplary way that Conrad Schick here, as in some other areas, represented buildings as they seemed likely to him, but which he did not (or only partially) know from his own observation and could not have surveyed himself17 (Fig. 8,9). This north-western building, shown in the plan as a continuous hall, was divided into several smaller compartments, at least in the northern part.

Fig. 8 Section of the hall in the northwest, today part of the Omar Mosque (photo: Jürgen Krüger, 2011).

Fig. 9 Correction of Conrad Schick's plan in the area of the north-west hall, as required by new findings (ground plan by Conrad Schick, 1900, as published; building survey Dorothee Heinzelmann, 2011; combined projection of the two drawings; Dorothee Heinzelmann 2020).

Further south, the Patriarch's Bath was located in the west on the Patriarch Road (today Christian Quarter Road). It is uncertain whether the bath could also have been used for hospital services. However, it can be assumed that washing and toilet facilities were probably located in its vicinity, even if no such findings are known in this area.

In the east of the Muristan area, within another spacious hall, there is a large two-aisled cistern in addition to former oven installations. Here probably were located a kitchen and service rooms. Different heights of floors and vaults indicate that the building was not a uniformly continuous spatial unit. Latrines in the northeast corner of this wing suggest a latrine tower similar to the latrines of the Hospitallers complex in Akko18. Another large latrine and basin complex to the west of it probably belonged to bath houses.

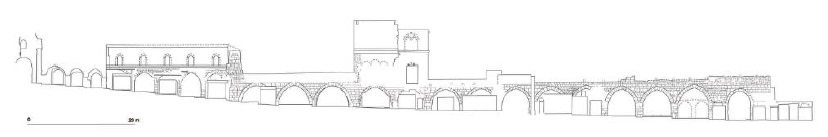

In the southern part of the area, along David Street, an extended, three-aisled hall has been preserved, which opened in big arches towards the street. Even though the arches and the rooms behind them were later provided with different installations and modified for use as shops, the whole basic features of the architecture with piers made of large sized stone blocks and accurately-built groin vaults are almost completely preserved from the time of the crusaders. A building survey of the entire façade along David Street could have been produced on the basis of photogrammetry19 (Fig. 10,11).

Fig. 11 Architectural survey of the north side of David Street, partly obscured by later additions (photogrammetry: Alexander Grünig, Matthias Zuckschwerdt; drawing: Dorothee Heinzelmann, 2007).

The wide arches could likely have been closed by inserted wooden walls and gates. Nevertheless, the open and flexible form of the street-side façade more likely indicates that this was the site of warehouses, stables and utility rooms, not of hospital rooms20. Due to the proximity to St. John's Church, to which there may have been a direct access, we assume the dormitories of the brothers of the Order on the upper floor of the south wing, which in case of necessity could also have been converted into rooms of hospital purpose, as reported in sources.

To the southwest is St. John's Church, which, together with the surrounding buildings, now forms a closed district within the Muristan. Investigations by the École Biblique in recent years have shown that the original building of St. John's Church, an irregular triconch structure with a corridor to the west, probably goes back to a pagan building of Late Antiquity, which was erected on the edge of the Roman forum21. It is not yet possible to determine the period from which this building was used as a church. But probably it had been in use as such from the time before the arrival of the crusaders at the latest, since citizens from Amalfi had already operated a facility for accommodating pilgrims at this site under the patronage of St. John. At that time, or very shortly after the arrival of the crusaders, the building was renovated and an upper floor was added, so that the building had two-storeys. Both floors were only accessible separately, there was no internal communication. The upper floor is accessible from the west via a forecourt from the Christian Quarter Road. In the basement there was a pre-existing entrance from the south, which was later blocked from the outside by a cistern, but may have still been in use during the Crusader period. At that time, an entrance from the northeast was newly built, leading down from the area inside the Hospitaller buildings, which probably formed a courtyard. This opening thus provided a direct access for the Knights of St. John. We assume that St. John's Church was the church from which the Order took its name (Fig. 12).

5. Résumé

Even if many questions still cannot be answered satisfactorily, the observations made so far give an increasingly better picture of the structure of the Muristan during the time of the presence of the Order of Saint John. The following sketch shows an attempt to map the distribution of functions and building units, as it currently appears likely for us. Conrad Schick had given room to the idea of a large hospital with his overall plan. This was right and important 120 years ago in order to understand the building remains to a certain degree. Today, research shows that we have to distance ourselves from the “grand ideal plan” and consider it in a much more differentiated way. Reality was more complex. Therefore, despite some progress, important questions remain unanswered, which may be better understood in the future on the basis of a broad collection of material and further research, and with better conditions of accessibility and examination possibilities of all preserved buildings. There is reason for hope as the various investigations of recent times in the area of the Greek bazaar have shown repeatedly. There are still areas that have not yet been explored. And there is the real hope to find or to identify further manuscripts or sources, as has been the case several times in recent years, which can provide further insight into the Muristan and its functioning (Fig. 13).