Introduction

In the art of the medieval and early modern eras, in Christian Western Europe, Mary Magdalene is usually identified by the vase she holds1. Often referred to as her ointment jar, it is a commonplace to see this object as the alabastron of perfume that the sinner woman from the gospel of Luke broke to anoint the feet of Christ, or in her other guises as Mary of Bethany who anointed Christ and wept for her brother Lazarus’s death, to Mary of Magdala who came to anoint Christ’s bodily remains and wept in the garden at both his loss and his return with witnessing the Resurrection2. Further to this last scene she is identified with that other figure of tears and perfume, the Sponsa of the Song of Songs3. Hence perfume is in some sense the binding agent of the fragments that comprise this composite figure of Mary Magdalene, and it comes as no surprise that the jar containing it should serve as her primary attribute. While the saint’s tresses and tears are significant symbols in the Christian experience of salvation, which I have explored in depth elsewhere4, our focus in this article will be that vase.

Other studies of Mary Magdalene, such as the major works by Susan Haskins5 and Katherine L. Jansen6, by necessity mention her ointment jar. Such studies, however, have largely left untapped the rich meanings and connotations of the vase beyond its functioning as a “simple” iconographic signifier, that is, as a univocal means to identify the Magdalene within the Christian cohort of saints. Images may be brought before the reader, but the vase is generally only mentioned as the object that permits the author to name the figure. There has been no systematic analysis of the significance of the Magdalene’s vessel. I propose in this article to offer that analysis through a coherent corpus that explores the dense potential meanings of this symbol beyond a one-to-one correlation of identification with the biblical alabastron. To better isolate the object of our study, the vase, we will concentrate - with some exceptions - on individual painted figures of the Magdalene either alone, or in polyptychs or other types of pala, such as sacra conversazione.

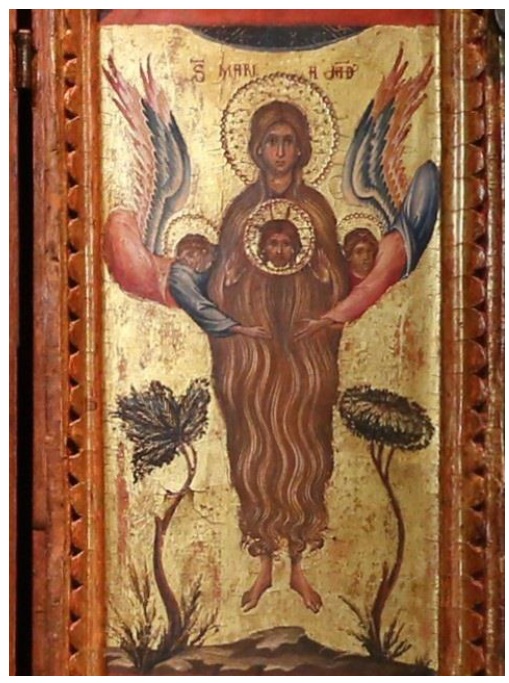

For its geographical and chronological boundaries, this corpus focuses on Italy, foyer of the initial explosion of Christian imagery in the thirteenth century to its apogee in the sixteenth, thus covering the later Middle Ages to the early modern period. My reference in this is of course based on the reasoning of Hans Belting7, especially with his notion of the invention of “indigenous icon” and the polyptych and pala figures that this eventually becomes. This is further based on the fact that the peninsula was at the forefront of Magdalenian iconography since this invention, and the effects of Mendicant - especially Franciscan - patronage that so invested this saint with their particular strain of piety, the inventiveness of peninsular artists, especially as applied to the alabastron, continuing from the 1200 painted cross of a Greco-Italian painter, through to the early modern era with Titian’s 1535 Pitti Magdalene. After this period, with the Counter-Reformation’s more formulaic directives, the vase seems to lose some of its density of meaning. For the period considered, the thirteenth through the sixteenth centuries, the results will demonstrate that the vase holds an intimate connection with her bodiliness, and her role in the narrative of redemption.

The Conceptual Framework of the Imaginary

Mary Magdalene as Vessel, through her Association with the Body

To begin with, a vase, in fact, might stand as a metaphor for the body in quite disparate cultures. It is present in ancient Judaism such as when Hosea 8:8 declares, “Israel is swallowed up; already they are among the nations as a useless vessel”. It occurs again in Jeremiah, for example, when the prophet exclaims, “Is this man Coniah a despised, broken pot, a vessel no one cares for?” (22:28) or again, “He has made me an empty vessel” (51:34). It is this notion that Paul brings to bear in comparing the body to clay vessels (2 Cor 4:7). We see it again as far away as the Italian peninsula in Etruscan culture in the anthropomorphic terracotta pots used as urns8. Thus, we can see that the vessel is a metaphor for the body in both Judeo-Christian thoughts, as well the indigenous plastic Italian imaginary.

As concerns the period examined in this article Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) also thinks in terms of a container when he contemplates the nature of the body after the Resurrection:

“This brightness that is in the spiritual soul is received in the body as corporal. And thus, according to whether the soul will be of a greater brightness by its superior merits, there will also be a different brightness in the body as the Apostle says, I Cor. 15. And it is thus that the glory of the body will be known in the glorious body, as is known in the glass the color of the body that is contained in a vase of glass, as Gregory says on Job, 28: 17, ‘Nothing will be equal to it, neither gold nor glass’ "9.

This is particularly apt to pair with the Magdalene, whose very composite creation through the different biblical episodes from which she is created is centered on the issue of the human body and its destiny. That is to say, she is the one who anointed Christ, the Anointed, the Incarnation of God, bodied forth into this world for the salvation of humankind. As peccatrix, she was considered to have sinned with her body, to thus be damned to perdition, but through her conversion, commonly understood as the moment she covered Christ’s feet with her perfume, she was destined to be the first to witness the resurrection of his glorious body - and to possess her own glorious body in turn, instead of being destined to damnation of that body. A vase thus encapsulates many of the primary issues that the Magdalene symbolizes, issues of sin and salvation as invested particularly in the somatic, whether it be her erring flesh or her intimate relation with the embodied Godhead.

Mary Magdalene as Vessel Through Her Sainthood

As concerns this last point the vase is also an apt symbol of her sainthood. Let us look to another sainted, converted sinner as an example, Paul. Commentary on Paul’s description of the body as vessel designates him as a “chosen vessel” (Acts 9:15).

Thomas Aquinas’ disquisition on the Epistle to the Romans elaborates the role of the Apostle as vase. He contains the sacred oil of the name of Christ from the exegesis of the Song of Songs. He is recipient of the precious liquid of Grace10.

This image extended to other holy figures: avatar of the saint, “second Magdalene”, Margarita of Cortona is described too as “truly a vessel of sanctity” abounding in light and perfume11. One of Paul’s most famous verses in this epistle, “where sin flowed, grace overflowed”, reiterates this image of a container that pours12. It also became customary to apply these words to Mary Magdalene as evidenced in the writings from Ambrosius of Milan (c. 340-397) to William of Auvergne (1180/90-1249)13. Dominique Iogna-Prat underlines the emphasis given to this sort of pouring forth in the leitmotiv of the word “effundere” repeated in the Sermo14. Hence as saint, the Magdalene is also a vase pouring forth the grace of Christ.

The equivalence between the body of Mary Magdalene and the vase she holds is reiterated in writings celebrating her sanctity, her conversion. One hymn sings, “From a basin, become a cup/ Gone from mud to light / Transposed into a vase of glory”15. Jacopo Passavanti (1302-1357) expresses the metaphor succinctly in giving her the words “this fragile little vase of my body”16. In these years Giovanni di San Gimignano (c.1260-c. 1333) describes her as recipient17 as does Iohannis de Biblia (d. c. 1338)18. The Rappresentazione della Conversione di Maria Maddalena, written in the mid-fifteenth century and printed in 1554, renders the equivalence yet more concrete. As she prepares her vase of perfume as offering to the Anointed, the saint is given these words and directions: “Receive me, who gives all of me to you”. “Me” in the instance seems to refer to herself, of course, but also to this essentialized symbol of herself that is her ointment jar and its contents19.

Mary Magdalene as Vessel Through Her Womanhood

Furthermore, she is vase by definition of her femaleness. In the early fourteenth century, Dante (c. 1265-1321) utilizes the image in speaking of the “natural vasello”20 of a woman’s genitals. The poet’s widespread fame and broadly diffused work throughout our temporal framework leads us to believe that this symbolic equivalence was commonly accepted. His contemporary, Franciscan Ubertino of Casale (1259-c. 1329), describes Dalilah as a receptacle of lust21, as was the Magdalene before her conversion. Ubertino’s spread this kind of imagery far and wide in his sermons throughout Tuscany and Umbria at the end of the thirteenth century and with the fifteenth century incunabula of these sermons in the friar’s immensely popular Arbor Vitae Crucifixae Iesu. In spite of his disappearance in an odor of heresy, in the following century, another indefatigable Franciscan preacher, Bernardino of Siena (1380-1444) was never without his pocket copy of this book. Alter ego of the Magdalene post-conversion, Mary, the Mother of God, is described as a sealed vase in reference to her hymen. Images of her birth and of the Annunciation, in which she conceives Christ, are traditionally marked by the representation of vessels. Clarissa Atkinson aptly titles her essay on the medieval concept of virginity citing the period description of “a precious balsam in a fragile glass”22.

If the vase can signify the sexual organs, it also indicated the heart. Already with Aristotle (384-322 BC) the heart is compared to a vase as container of blood23. Doubling back to femaleness, the heart in turn could be understood as a kind of womb, as we can trace back as early as Albertus Magnus (c. 1200-1280)24. And this vase-heart-womb is the highly somatically charged locus of femaleness in which the Magdalene distills her ointment. From Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153)25 to Savonarola (1452-1498)26, the Magdalene’s heart was the place in which she created the perfume which she offered to Christ. This is in keeping with the understanding of physiology in the later Middle Ages in which the heart was the locus of the most subtle of humoral and spiritual decoctions, as has been remarked by Jérôme Baschet 27.

The integrality of women’s bodies was also considered under the form of a receptacle. Medieval physiology attributed to women a more liquid nature, given to tears, monthly bleeding, and lactation. Even their longer hair was understood as a sort of humoral effluvium28. Thus, the hair and tears that also identify the Magdalene are, as organic, somatic and above all liquid components of her person, in and of themselves the structural counterparts to her vase, insofar as vessels are made to contain such watery substances. These fluids so ruled the notion of a woman’s physicality that Odo of Cluny (c. 878-942) describes woman as a sack of filthy excretions29. This notion of container travelled down through the centuries and served as model even for the holiest of women. The later medieval period saw the rise of female mystics noted for the miraculous fluids issuing from their bodies or containing somatic miracles in their internal organs which would be opened by dissection, especially as regards the late medieval female mystics of Italy and elsewhere, such as Margaret of Città di Castello (1287-1320) or Claire of Montefalco (1268-1308)30. André Vauchez has remarked that this aspect of their spirituality coincides with their gift for prophecy, the root of which lies in the idea of women as recipients31. It is this same paradigm that renders women like the Magdalene more vulnerable to possession by demons, often through their sexual anatomy32.

As the new Eve, woman bears the news of Salvation, bringing forth life as the first woman brought forth death. When this is described, it is in terms of containing and pouring. For Ambrose it is her mouth - so anthropologically tied to the concept of the recipient, indeed to female organs - that brings news of redemption33. Hymns devoted to the Magdalene speak of the grace diffused from her lips34. The latent idea of the woman as vase underlying these formulations is brought to the fore by Gregory the Great (c. 540-604) when he describes how the Magdalene’s role inverses that of Eve: “From that hand the drink of death was given to you, now take from it the cup of life” or again in the Sermo, “From she whose hand poured for you the concoction of death, hear now from her mouth the joys of the resurrection”35.

The Magdalene is vase by still another means, yet again through her womanhood. Ever since her association with the Bride of the Song of Songs, as well as with Eve, commentators insisted on her great beauty. This was even part of the source of her downfall in the hagiography36 though Jacobus of Voragine (1230-1298) notes that after her conversion she is still splendid of body37. At the end of the period this article examines, when the female body was understood through the lens of Neo-Platonic Petrarchism, Agnolo Firenzuola (1493-c.1545) wrote the Dialogo delle bellezze delle donne. Here, as Elizabeth Cropper has shown, the charms of the female physical form are analyzed as different types of vase, an idea which Italian painters of our latter period willingly adopt, even for religious paintings, such as Parmagianino’s Madonna of the Long Neck of 1535-1540, in which the artist draws a metaphorical and formal parallel between the large vase in the canvas and the exaggerated forms of the Virgin’s body38.

When contemplating images of the Magdalene holding her vase, we can posit that, conceptually, a spectator, male or female, educated or not, understood it on some level at least to be not only the container of perfume that anointed Christ, in and of itself rife with theological meaning. Our references above have been both savant and popular, available through bookish culture but also through oral diffusion - hence a vast swath of the population of the peninsula when confronted with an image of Mary Magdalene holding her vase, specifically in the examples that follow in the next section, would be apt to make the metaphorical connection between the container and she who handled it. This vessel then designated the body of the human creature in general. More specifically still it signified the woman’s body, and even more so a beautiful woman’s body. And yet more pointedly still, it was that instrument by which she transgressed, her own sexual organs, as well as the heart by which she redeemed her sinful body.

Mary Magdalene and Her Vessel: A Pictorial Theme

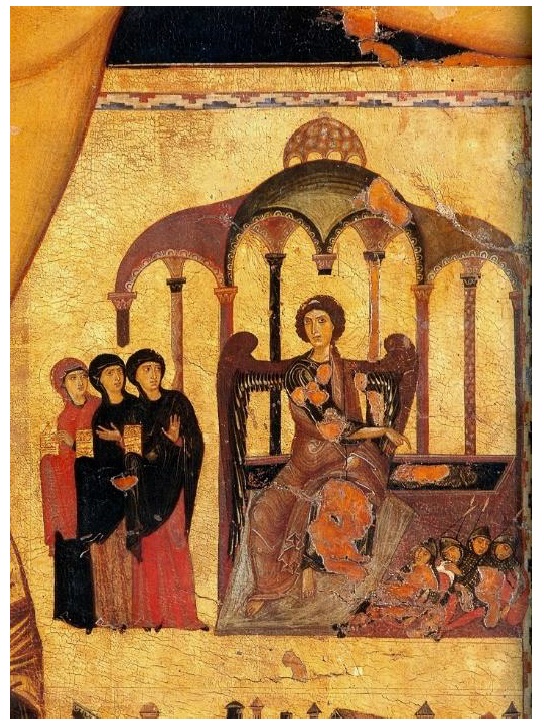

The vessel reaches back to the origins of her pictorial representation. It is the vessels in the hands of the women depicted on the wall of the House Church in Dura-Europos39 that suppose their identity as Mary Magdalene and “the other women” by the third century of the Common Era. The same scene of the Women at the Tomb, or that of the Resurrection of Lazarus, is often carved into the sides of paleo-Christian sacred vases - pyxes, reliquaries, and ampullae - loci in the Mediterranean world, at least, of her early iconographical development40. These recipients further link the Magdalene to the concept of the vessel. It is in later years however, starting especially in the thirteenth century and onward that this association with her receptacle grows more intimate. What follows will be an attempt to trace that relationship and understand the meanings associated with the symbol that stands for Mary Magdalene.

The Vase and Its Meanings by Association in the Polyptychs

The Prophetic Vase: Guido da Siena’s Dossal N° 7

The presence of the Magdalene, as among the saints in Guido da Siena’s thirteenth century dossal (Fig. 1) to the Sacra Conversazione of the early sixteenth century, is so common as nearly to defy the construction of a comprehensive corpus. In this section, however, we will examine closely the meanings of the vase as far as can be deduced by comparing it with the iconographical attributes of other holy figures joined with her in these images - the most often indicative of a sort of “spiritual manifesto” of the church concerned and the objects that identify them41. Guido’s work, the oldest surviving dossal, announces the great tradition of the Sienese polyptych of Duccio and Simone Martini which will be exported throughout Italy. The iconographical choices therein will in turn affect ulterior representations of the Magdalene as one among the saints surrounding the Virgin. We will see in what ways the meanings implicit in that iconography survive and how that continues to affect the signification of the Magdalene’s attribute through the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

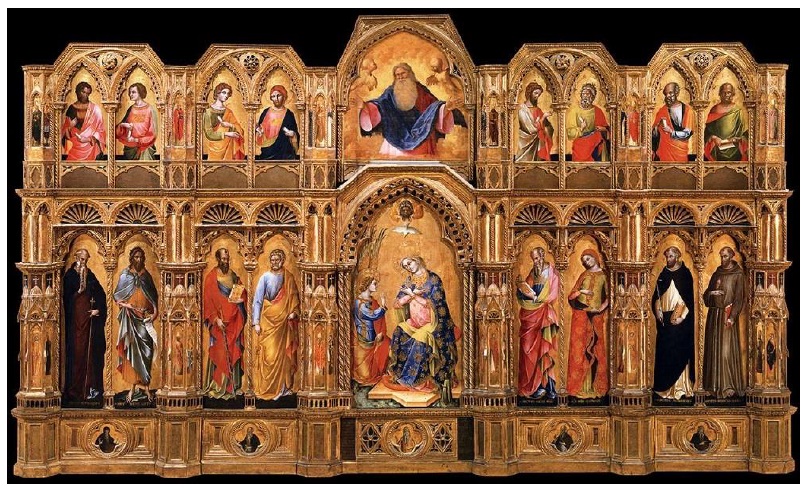

Fig. 1 Guido da Siena, Virgin and Child surrounded by Saints, c.1270, tempera on wood, 96x186 cm Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena. (photo: Sailko, Wikimedia Commons, in public domain).

This dossal (Fig. 1), inscribed with the date 1270, by Guido da Siena, most likely for a Franciscan church in the region, is among the first known of this kind of grouped altarpiece. Even if it has been truncated, and therefore possibly iconographically incomplete, we can, with what we see, pursue a satisfying analysis of the spiritual manifesto desired by Guido’s patrons42 . How should the spectator understand the the selection of the Virgin and Child surrounded by Saints Francis, John the Baptist, John the Evangelist, and Mary Magdalene? The overarching theme, which we will see again in Simone Martini’s (c.1319) Santa Caterina altarpiece for the Dominicans of Pisa43 as analyzed by Joanna Cannon, is that of the medium of communication and writing44. And we will see how the vase plays into this theme, though in a quite differently accented Franciscan tone.

In Guido’s dossal, all the figures are associated with hermitism. The Baptist wears animal skins which isolate him from civilization. The Evangelist took refuge on Patmos, as did the Magdalene’s in the south of France according to medieval legend. Francis spirited himself away on Mount Alverna. Underlying this theme of hermitism is the theme of prophecy. The first John bears the scroll of Old Testament prophets, of which is he is the last. The second John bears a codex. This evolution to a new form of book was taken as signifying the passage towards the age of Grace through the birth of Christ, as announced by the Evangelists. Of these four, John of Patmos is usually considered the most mystical as well as the most prophetical, since he was also the author of Revelation, predicting the second coming of Christ. In fact, the book this last prophet holds, with its five circles analogous to the two on Francis’s book cover, seems less to represent the Gospel than his visions of the Apocalypse, as we will see. Firstly, the two tomes resemble each other closely. The pages of the open book are as red as the cover of the closed one. These two tomes seem to be in fact one, at least figuratively, metaphorically. This would in turn hearken to a major preoccupation of Franciscan exegesis, a prophetic preoccupation of John’s foretelling, Ap. 5:1, that is: “I saw, in the right hand of he who sat on the throne, a book written both within and without, sealed with seven seals”. The two books combined, as imagined by Guido da Siena, placing them in the hands of Francis and John of Patmos, seem figuratively to point to that very description of a book inscribed upon both inwardly and outwardly. Moreover, the seals that mark these tomes are also a reference to Franciscan prophecy. For the Friars Minor considered Francis to be the angel of the sixth of the prophesied seven seals, as announced in this Johannic passage. It is then the sixth and seventh that the Poverello bears on this book, and the saint’s two stigmata that mark his hands are twinned to the two seals of the book they hold - these wounds were said to be the “seal” of God the Father45. Francis, as this angel of the sixth seal that John announced, would open the new age of faith46. With this passage, just as the Baptist announced the coming of Christ and the new era, the prophet of Patmos foretold the coming of Francis, Alter Christus, and a turning point in the history of salvation.

The vase, though not a support of writing as are the other iconographical signifiers, is coherent with this interpretation. The Magdalene offered it to Christ “in preparation for my burial” hence by premonition, by secret knowledge. She is an initiate of Christ’s secret teaching, of the mystery of the Incarnation, according to Richard of Saint-Victor (d. 1173)47. It is the source of her eloquence when converting the pagan population of Marseille, as her apocryphal legend held48. This legend was an extension of her role of Apostola Apostolorum, Apostle to the Apostles, as named so by Hippolytus of Rome (c.175-c.236), title she earned as first witness to the Resurrection. Here her hand gesture seems to mark that role, hailing the viewer with her good news of the salvation of the body as symbolized by the vase, the glorious body resurrected, as held in the other, a future promise. This gesture will be echoed throughout the next generation of Magdalenian iconography as we will see notably in the Florentine altarpiece of 1285 by the Master of the Magdalene which also develops the idea of the Magdalene as prophet by way of being a receptacle.

Further to this, of all these supports of writing - the two books, and the two scrolls - in the end none of the communication here is legible and only that of Francis allows us to see what is written. Yet, as pseudo-kufic lettering, it is as impenetrable to human intelligence as the closed book and scroll. Intellectual parsing is beyond our means. This is not a fault of the artist, but a well-thought-out execution of a symbolic idea. The epigraphy spreads undecodably over the red surface in a kind of mystic, rather than intellectual, enlightenment. The gold becomes a reference to the Word made flesh, the Light at the beginning of the word held in the arms of the Madonna, the incomprehensible mystery of the Incarnation.

The Magdalene’s vase perfectly integrates this Incarnational, indeed sacramental reading. The cylinder with its conical lid recalls the form and the substance given to liturgical vases. The white veil hearkens to the winding cloth around the body of Christ (the Eucharist) which this vase will anoint, as much as to the chalice veil, or other ceremonial cloths of use in Holy Communion, such as those which the celebrant uses to hold the various sacred recipients49. The Sermo of Odo of Cluny explains that the saint is initiated into the mystery of the Humanity of the Word - that later she is supposed to have “diffused” like her perfume50.

The Prophetic Vase After Guido da Siena

Though widely varied in context and patronage, in most of the altarpieces that we will examine in this part, the Magdalene is painted in similar company, witnessing the enduring meaning of these theological pairings.

Duccio’s Polyptych N°. 47 (Fig. 2), painted after 1311, includes John the Evangelist with his book, and John the Baptist with his cross, while placing the Magdalene and her vase - covered here with pseudo-kufic writing - under the aegis of the prophets Malachai and Daniel. On his scroll the former holds the words “ecce ego mitto a(n)g(e)l(um) meu(m)/qu(i) p(re)parabit via(m) ante facie(m) tuam” (Math. 11: 10), while the latter’s reads “Lapis imprecisus (sic) d(e) monte sine minibus”51. Duccio’s representation of the vase with its mysterious script seems to condense the pseudo-kufic calligraphy of Francis and the vase of the Magdalen in Guido’s dossal. In the context of Duccio’s theological program, the prophetic association seems to voluntarily recall the impenetrable writing on the wall of Nebuchadanezzar from the Book of Daniel and perhaps the ability of the Magdalene to grasp sacred enigma, as we have seen from the excerpts from Richard of Saint Victor and Odo’s Sermo. We can understand the sense of Malachai’s quote as her witnessing the resurrected Christ, seeing the revealed Savior face to face.

Fig. 2 Duccio, Polyptych N°. 47, 1311 or after, tempera on wood, 184x257 cm Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena (photo: Comubusken, Wikimedia Commons, in public domain).

Simone Martini’s Orvietan San Domenico Polyptych52 from the early 1320s has a Dominican origin. The Magdalene holds her vessel while a tiny portrait of the patron kneels at the bottom of her frame. According to de Castris’s reconstruction53, she is surrounded by Saint Peter and his book and key, and Saint Dominic with lily and book, while Paul occupies the other flank of the polyptych with his letters. Once again, the vase integrates a context of the written word as in Guido’s altarpiece (Fig. 1).

The same goes for another of his works for the Preachers, the Santa Caterina Polyptych of the Pisan studium. Here the artist has given to the Magdalene’s other hand a subtle gesture of benediction in keeping with the vase as pyx, or as element of the diffusion of her own fragrant predication, for she is in fact twinned to the preaching figure of Catherine of Alexandria on the other flank of the altarpiece, and next to Saint Dominic on her own side. That other figures include John the Baptist and John of Patmos is now entirely unsurprising after the initial grouping of these figures by the patrons of Guido da Siena54.

Lorenzo Veneziano, for instance, in the years 1357-1359, on his Polyptych Lion, places his Magdalene, with golden vase, between John the Evangelist, Dominic, and Francis55 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Lorenzo Veneziano, Polyptych Lion, 1357-1359, tempera on wood, 258 x 432 cm, Galleria de l’Accademia, Venice (photo: Sailko, Wikimedia Commons, in public domain).

To take one later polyptych which shows the lasting influence of the reading we have given to Guido’s dossal we might look to Gentile da Fabriano’s Valle Romita Polyptych of 1410-1412 (Fig. 4). The Magdalene with her vase - which looks more and more like a monstrance, etched now into the gold-leaf background - is placed beside Dominic with his book which contains his theology, and paired on the opposite side with Jerome holding a miniature church, a stand-in for his translation of the Bible. As this allowed for a radiation of the Christian religion by holy scripture, the church door “radiates” gold striations, as does the side wound of Francis next to him. This wound also propagated the Faith as did Dominic with his preaching. Jerome’s church also points to the Magdalene’s role as Ecclesia, the Mystical Body of Christ. The references to the programs painted by Guido da Siena (Fig. 1), in which the vase is a place-keeper for the spreading of the word of God, are evident.

This continues through the Quattrocento, associating the Magdalene with Church Fathers and with John the Baptist. An altarpiece dated to 1466 and attributed to Benozzo Gozzoli shows her with her jar next to John the Baptist with Martha and Augustine56. Botticelli’s Saint Ambrose Altarpiece of c.1470 places her with a vase in her hand in company of, among others, John the Baptist and Francis57. Neri di Bicci’s Virgin and Child commissioned in 1477 is surrounded by Saints John the Baptist, Clare, Francis, and the myrrhophore Magdalene in the church of Saint Martino a Mensola58. At the turn of the sixteenth century Mantegna’s Virgin and Child is surrounded by the Baptist and the vase-holding Magdalene59.

The Somatic Implications of the Vase: Medicine, Healing, Death, Resurrection

This is not to say that each of these altarpieces gives an identical sense to the vase. The individual groupings bring to the fore a different meaning. For all the prophetic implications of Duccio’s Polyptych N°. 47 (Fig. 2) we must also recall that the altarpiece was painted for the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala60. Under the care of the Cistercians61, this brings to mind Bernard of Clairvaux’s sermons on the Song of Songs which identifies the oil of the Bride with the name of Christ that is a healing medicine62, indeed kept in a small vase63. This image is traditional in Christian exegesis since Augustine (354-430) called Christ an apoteca and it is in this sense that Jacobus of Voragine calls Christ a shattered alabaster jar64. Across medieval Europe, hospitals were furthermore frequently dedicated to the Magdalene65. The perfume of the Magdalene then was associated on one hand with the suffering body subject to death, and on the other that even in death there would still be eternal life offered in the salvation she symbolized, that any sinner might also be redeemed and come then, as she had done, face to face with God who had been made flesh and defeated the punishment for transgression. That face-to-face meeting is even foretold, as we have seen above, in the inscribed writings of the prophet associated with her.

This association with the suffering body was not unusual. A fifteenth-century fresco in the chapel of a former hospital in Alatri shows the saint reaching out from behind the painted loggia to offer her jar to the bleeding Christ in form of an Imago Pietatis in the loggia next to her, and by way of that very gesture, to the spectator (Fig. 5). The placement of the vase visually “rhymes” with the outpouring of the sacred blood from Christ’s side wound. In the very early sixteenth century, as far away as France, the Saint Bartholomew Altarpiece shows this perfume jar in the hand of the Magdalene, as if offered to the viewer present in its place of origin, the Antonite hospital in Paris66. Hence the vase signifies the body in its passible suffering as well as its source of hope, be it the healing of the flesh by medicine or the salvation upon death in which the soul meets its maker “face to face”.

The Somatic Implications of the Vase: Sins of the Flesh and Grace’s Vessel

We have looked at Simone Martini’s San Domenico Polyptych and analyzed there the use of the vase as influenced by the meanings given it by Guido da Siena. The Orvietan work, however, adds another layer to the meaning given to the vase. Paul, her visual counterpart in the iconographical layout of the polyptych, is the Apostle, the “chosen vessel” (Acts 9:15) from which grace overabounded where sin had abounded (Romans 5:17 and 5:20). We know that this description was also applied by commentators to the Magdalene, the Apostola Apostolorum, who is here the Apostle’s spatial and conceptual counterpart. Moreover, Paul’s letter, symmetrically twinned to the Magdalene’s vase, is inscribed with “Ad Romanos”. It is in this same Epistle that Paul delineates human beings as vases of different materials: clay, wood, silver, and gold, that God, as a potter, has made according to his will. It is also this letter that sketches out the differences in nature between the passible body of mortal life and the subtle glorified body of the resurrection. This can be understood as reiterating the vase which his visual complement holds is also to be understood as a metaphor for the body which is subject to death but also to transformation into a glorious state.

When we find the Magdalene paired again with Paul, some years later in Venice, in Lorenzo Veneziano’s Lion Polyptych, the association is perhaps motivated by the same thinking (Fig. 3).

Still later, we find them together again in the sacra conversazione of Raphael’s Ecstasy of Saint Cecilia from 1514-1517 in the company of John the Evangelist and Augustine. (Fig. 6). Daniel Arasse and Stanisław Mossakowski have analyzed this iconographical program, seeing the underlying themes of love, virginity, sin, conversion, and mystical contemplation that joined the Apostle to the Apostola67. Paul holds, along with his traditional sword, two letters which are not inscribed. They have convincingly been supposed to be the Epistles to the Corinthians for their exposition of the nature of conversion and mystical love68. Within a passage that addresses these issues, Paul once again resorts to his metaphor of the body as vessel containing divine Grace (II Cor 4:7).

Fig. 6 Raphael, Ecstasy of Saint Cecilia, oil transferred from panel to canvas, 220x136 cm, 1514-1517 Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna. (photo: Attilios, Wikimedia Commons, in public domain).

In this play of interpretation by association, another frequent grouping is meaningful. Niccolò di Segna’s altarpiece of 1337 links the Magdalene and her vase with Saint Lucy69. In Venice we find this assemblage in the 1427 Sant’Elena Altarpiece by Michele di Matteo70 and later in Sebastiano del Piombo’s Pala di San Giovanni Chrysostomo of 1511 (Fig. 7).

Lucy is, like most other martyrs of the Catholic host of Saints, and unlike the Magdalene, a virgin. This virginity hearkens however to both perfume and container. It is, of old, referred to as a sweet unguent and as balm contained in a breakable vessel. In her offices, Lucy’s virginity is described as habitaculum for receiving God71, a word usually translated as “abode”, but also chosen for the womb of the Virgin Mother. Hence, we see her often holding a vessel. Furthermore, Lucy’s virginity was challenged in the process of her martyrdom by placing the maiden in a brothel. The receptacle therefore also refers once again to the female sexual anatomy, accentuating this signification with regard to that vase the Magdalene holds when paired with the martyred virgin.

Vase and Vision: Seeing the Resurrected Christ

Another shared theme between Lucy and the Magdalene is vision. This too then is a reference to the acts of the body and its suffering. Since the martyr’s eyes were pierced, Lucy was the patron of visual maladies and, when not holding the receptacle of her virginity, frequently portrayed carrying her eyes. Another way of giving expression to this was to picture her vessel as transparent, as with Sebastiano del Piombo, itself deriving from Giovanni Bellini’s portrayal of the martyr in his San Zaccharia altarpiece of 150572. One of the great turning points on which the Magdalene’s theological importance rests is, of course, her witnessing of Christ’s resurrection, her act of seeing. John’s verses describe the Magdalene weeping, as she initially mistakes Christ for the gardener before fully recognizing him. Theologians took this to mean a conversion from the spiritual blindness of doubt to sight and perfect faith73. Another reading of the scene commonly interprets this passage as that of moving from the touching that characterizes her attachment to the physical presence of the Incarnate flesh to a more spiritual understanding of his purpose, moving along an anthropological hierarchy from touch to sight, acts of the body growing progressively less physical and more spiritualized.

Fig. 7 Sebastiano del Piombo, Pala di San Giovanni Chrysostomo, 1511? oil on canvas, 165x200 cm, Church of San Chrysostomo, Venice. (photo: Sailko, Wikimedia Commons, in public domain).

So, Sebastiano del Piombo gives us a Magdalene holding gold and a Lucy holding glass and this seems to hearken to the very passage of Thomas Aquinas that we opened with, in which the resurrected body, the glorious soma, is compared to both substances, surpassing them. Virgin Martyr and Converted Sinner summarize the states of what the saved body will become at the resurrection.

The Vase and Its Substance in Artistic Representation

Gold

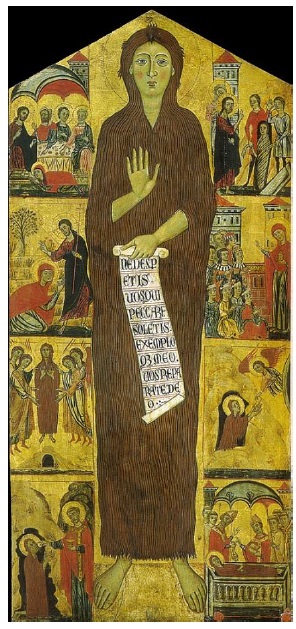

If the gospels describe the vase as made of alabaster, this is not the only substance imitated for its rendering. The Magdalene makes her first appearances in medieval Italian art on the side panels of painted crosses. The tabelloni of a thirteenth century cross (Fig. 8) show her with the other women bearing a golden jar of ointment to the tomb, against a gold leaf background74. Guido da Siena’s dossal seems to quote from this source in the vase he gives to his Magdalene (Fig. 1). If the fourteenth century ushers in the era of the vase depicted as alabaster that lasted throughout the sixteenth century, the gold vase will remain a viable visual alternative throughout our period. Even in the early years of this shift with Duccio’s Polyptych No. 47 (Fig. 2), the Sienese artist retains the use of gold in the pseudo-kufic chrysography that decorates it. As a fully gold object, it appears in the hands of the preaching Magdalene in the 1285 Florentine panel of the Magdalene Master (Fig. 9). We see it again as such in the fourteenth century figures of the Magdalene, for example in the 1320 Sienese polyptychs by Niccolò di Segna75 and Segna di Bonaventura76. It is golden in two altarpieces by Paolo Veneziano: on the predella of that of Chioggia77, and again on the altarpiece now in the Museo di Palazzo Venezia78. Paolo’s disciple, Lorenzo Veneziano, uses this same conceit in the Polyptych Lion (Fig. 3). We find it in gold in Tuscany still with the standing figure from Bernardo Daddi’s workshop of 1327-1348 79 and in the Crowning of the Virgin by the Maestro di San Lucchese c. 1340-137080. We find it once more in the bust figure of the saint by Antonio Veneziano (Fig. 10) who was active between 1369 and 1388 in Venice and Tuscany.

Fig. 8 Anonymous Greek or Pisan, Marys at the Tomb, detail, Crucifix, 1200-1210, tempera on wood, 298 × 233 cm, Museo Nazionale di San Matteo, Pisa. (photo: Eugene a, Wikimedia Commons, in public domain).

Fig. 9 Magdalene Master, Mary Magdalen surrounded by eight scenes of her life, 1285, tempera on wood 178x90 cm Galleria de L’Accademia, Florence. (photo: Tetrakys, Wikimedia Commons, in public domain).

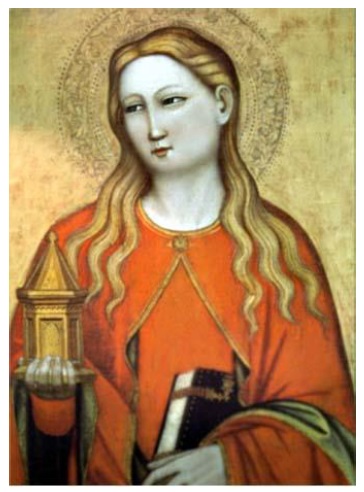

Fig. 10 Antonio Veneziano, Mary Magdalene, 14th Century, tempera on wood, dimensions unavailable, Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican. (photo: Migdalmat, Wikimedia Commons, in public domain).

It is current throughout the Quattrocento. In Tuscany, Fra Angelico depicts the vase as golden in his Crowning of the Virgin of 1430-1432 (Fig. 11) as well as in his standing figure of the Saint in the Cortona Triptych of the Virgin of 1433-1434 or 143781. We find it with Neri di Bicci’s Magdalene of 1477 and in Biagio d’Antonio’s painting of the saint of these same years. By the very end of the century, it still utilized by Filippino Lippi in his panel of the penitent figure82 and by Fra Bartolomeo in his altarpiece of The Holy Father, St. Mary Magdalene, and St. Catherine of Siena of 1508 for the Dominicans of Venice83.

Fig. 11 Fra Angelico, Coronation of the Virgin, 1430-1432, tempera on wood 213 × 211 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris. (photo: Eugene a, Wikimedia Commons, in public domain).

The Veneto and its orbit also use this device, as in Gentile da Fabriano’s Valle Romita (Fig. 4) and Quaratesi altarpieces from the first half of the fifteenth century84. Thus, we see it also in the Sant’ Elena Altarpiece of 1427 and Carlo Crivelli’s two standing Magdalenes, namely from the Saint Francis altarpiece of Montefiore of 1473 (Fig. 12) and from the individual panel of c.149285. As well, Sebastiano del Piombo’s Magdalene holds a golden vase in his San Giovanni Chrysostomo altarpiece (Fig. 7).

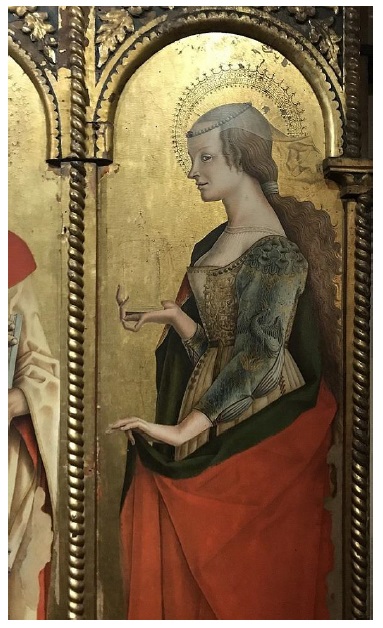

Fig. 12 Carlo Crivelli, Mary Magdalene, detail, San Francesco Altarpiece, 1473, tempera on wood, 174x54 cm, Polo Museale di San Francesco, Montefiore dell’Aso. (photo: DarTar, Wikimedia Commons, in public domain).

In the course of our examination of Guido da Siena’s dossal (Fig. 1), we saw that the gold of the vase and the saint’s handling of her attribute also clearly refer to it as a liturgical vessel, objects which themselves were made of gold, that noblest of substances. In the narrative panels of the Magdalene Master’s altarpiece (Fig. 9), the Eucharistic cup, the funeral censers, and the Magdalene’s vase are all depicted in gold leaf. Guido’s use of gold leaf in this work fits into a larger symbolic scheme as we have seen but is most concentrated in the vase which functions as a sort of magnet of bright reflective light, a second focal point in the composition of the Virgin and Child. This is emphasized by the gold striations on the Magdalene’s veil that seem, compositionally, to emanate from the jar. This elaborate plastic expression of the vase that will so influence and inform ulterior formulations should not surprise us coming from the hands of a Sienese painter. Already in the thirteenth century, the town was renowned throughout Europe for the craftsmanship of its goldsmiths in the fabrication of liturgical objects86.

By extension, of course, the gold expresses the sacred quality of the anatomy of the two Marys. This helps to explain that it does not distract from the main subject, that is the Christ-bearing Madonna, but rather reiterates her. Indeed, in the Sermo, the Magdalene is included among the number of the Virgins of the Apocalypse87. Hence the golden vase is seen in evidence in images of the Coronation of the Virgin such as that of the Maestro di San Lucchese and that of Fra Angelico (Fig. 11). The latter insists on the precious quality of the metal by placing it against a backdrop of marble steps leading to the Holy Couple.

The playing of one material against the other seems to hearken to Paul’s anthropology laid out in his Epistle to the Romans in which there are vases of common or of noble matter and usage. Elsewhere he names clay, wood, silver, and gold as substances the Creator uses to form the human body, but to different purposes (II Tm, 2,20). This last is the most exalted of all. That it is the most noble of substances we can infer from its position as the last element named Paul’s own hierarchical list. Furthermore, it was considered in our period to be the purest of substances, the most appropriate to liturgical vessels and that which the alchemists, be they Mendicant, be they secular, aimed to reproduce, without any “vile” component. Thomas Aquinas, for example, explains “chosen vessel,” that is Paul, is exegetically made of solid gold88. Moreover, the Angelic Doctor, citing Gregory on Job, returns to this metal when attempting to find some comparison to the nature of the subtle body of the resurrection to which, we recall, the period ascribes claritas89.

Placing this substance in the hands of the Apostola highlights once more her close association with the passage from the corruptible Adamic body to the incorruptible body of the Resurrection to which she bore witness. Fra Angelico for whom, according to Georges Didi-Huberman, the mottled marmo finto was an expression of the perfected form of Adam’s clay90, insists on this thinking in the play of the two materials in his Coronation (Fig. 11), by placing the gold against the background of the marble steps to the throne pictured. Filippino Lippi at the turn of the sixteenth century is making a similar statement in his portrayal of the haggard penitent, seemingly near leaving off her terrestrial existence. Her greyish, wasted flesh contrasts with the precious metal of the jar in her worn hand as a promise of what her body will soon become. In the Magdalene attributed to Biagio d’Antonio, the artist employs a similar device, but now harmonizes the gold of the vase with the blond tresses framing them, hence a continuum of comparison more than a contrast, as if to say that the body of the saintly sinner is not so much to be scorned and cast off in death as to be cherished for the message it can send of hope for redemption91. In the hands of different artists then, the visual metaphor is slightly inflected, but the reflection remains of the idea of this vase as a synecdoche for her whole body.

The use of gold to render the vase can further speak to the function of Mary Magdalene and the stuff or material of which her soma was understood by a period viewer. In the process of her conversion, she herself is changed into gold as described in the sermon of Gregory the Great which initially brought together the disparate biblical figures that comprised her92. Her name was etymologized to mean “she who receives light” and “she who gives light” in turn, the illuminata-illumnatrix93. This clearly motivates the use of chrysography by Guido da Siena in which her vase seems to radiate light in the striations that integrate her bright red veil (Fig. 1). This, along with her liturgical title of Mundi Lampas, is a satisfying framework in which to understand the choices of the artists above who portray her holding her vase aloft like a kind of lamp. Paolo Veneziano’s Chioggia Magdalene is an example of this as are the Valle Romita (Fig. 4), Sant’ Elena, and Montefiore (Fig. 12.) altarpieces as well as Fra Angelico’s Coronation (Fig. 11).

Alabaster

It is in the fourteenth century that painters begin to render the vase in white stone, evoking the material described in the gospels. We have seen that initially Duccio’s Polyptych No. 47 (Fig. 2) applies to the pseudo-kufic chrysography, but the substance of the vase is the alabaster. Simone Martini inherits this usage in the Santa Caterina Polyptych, as well as in his Maestà94. Such a rendering is spread through most of the bust figures emanating from a Sienese context for the rest of the century: Pietro Lorenzetti95, Ugolino di Nerio96 and Andrea di Bonaiuto97.

In the earlier Quattrocento, the white stone is still pictured. The Sant Andrea Altarpiece attributed to Benozzo Gozzoli shows the saint holding her large jar of alabaster. It is thus depicted in Botticelli’s Saint Ambrose Altarpiece. In the early years of the sixteenth century, we see it rendered this way in the Virgin and Child by Cima da Conegliano98. We see it again in Raphael’s Ecstasy of Saint Cecilia of 1514-1517 (Fig. 6), in the hands of Bernardo Luini’s bust figure from about 152599, and in Savoldo’s Magdalenes from 1520-1530100. Titian’s Pitti101 and Naples102 Magdalenes from 1530-1535 and 1567 also picture an alabaster jar.

Occasionally, this rendering shifts to marble. We find it pictured as such throughout the fourteenth century: in Simone Martini’s Santa Caterina Polyptych, or his Magdalene figure at Assisi, in the bust figure by Bartolomeo Bulgarini103, or that of the Maestro della Madonna di Palazzo Venezia104. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, it also marble in the hands of the Magdalene of the Virgin and Child in the church of Santa Maria Maddalena in Saturnia with the retable attributed to Benvenuto di Giovanni105. Luca Signorelli’s Magdalene for the Duomo of Orvieto of 1504106 or Bacchiacca’s bust of the figure from the 1540s107 are also associated with this pietra dura.

The stone in some ways signifies in a similar fashion to gold with regard to the subtle body. Alabaster was considered perfect for containing perfume insofar as it was thought to preserve all ointments from spoiling108. This resistance to putrefaction certainly recalls the incorruptible nature of the glorified flesh. Jean-Claude Schmitt has remarked how such materials, both hard stone and gold, could recall the saved body’s ultimate state in their use in such symbolically charged objects as reliquaries109. Paul Hills has attentively remarked how the veining of marble in particular might recall the corporeal veins of humans110, adding to this perception, while Georges Didi-Huberman signals how marble could point to the redeemed state of Adam’s soma111. The latter also points out how the mottling of the marble in the relic of the anointing stone was considered to be produced by the sacred fluids spilling from the crucified body112. If we accept his analyses, the alabaster, as a kind of stone, is more appropriate yet than the gold to represent the final state of the redeemed flesh insofar as it is closer in nature to the clay that composed the original man.

In a less obvious way than gold, it is also possessed of claritas, seeming to glow when in conjunction with light. This diaphanous nature was another quality shared by the subtle body. Though this aspect seems to become more important to the visualization of the vase in the fourteenth century, the dominant technique of egg-based tempera limited the realistic rendering of a purely translucent substance. The rise of oil painting in Venice at the end of the fifteenth century will change this. Concurrently a Florentine master like Verrocchio or his workshop could distribute pigment in an egg binding with such delicacy of hand as to imitate the finest of sheer drapery113, but not the absolute transparency of glass, for example. The Trecento has not arrived at this artistic acquisition, though it may be that the shift to alabaster in the representation of the vase announces a new preoccupation with the possibility of perceiving light through a given medium.

This semi-transparency was meaningful theologically, not merely as an artistic feat. If Mary’s virginity beyond parturition was legitimized by comparison with light penetrating glass, a similar logic was applied to Christ’s Resurrection. Jerome (347-419/20), and Thomas Aquinas after him, explain the association between the stone tomb and the miraculously virgin womb114. This analogy was borrowed again at the beginning of the fourteenth century in a Franciscan context by Ubertino da Casale115. In the sorts of theological parallelisms favored by Christian commentators we have seen how the two Marys were figures of a New Eve, counterpoint to the First. Many express, in various formulations, as we have seen in the first part of this article, that as a woman brought sin so a woman brings salvation. Additionally, we also find the hope borne by Mary the Virgin fulfilled in Mary Magdalene. “As the gates of paradise were opened to us by the Virgin Mary, who is the only hope of the world, and who was kept from the curse of Eve, by the blessed Mary Magdalene, the opprobrium of the feminine sex is erased and through her is offered the splendor of our resurrection, born in the Resurrection of the Lord”116.

The Magdalene is the Mary associated with this mystical birth that is Christ’s Resurrection and so the stone, this “pietra dura,” as the mid-Quattrocento dramaturge Castellano Castellani describes the tombstone in his Resurrection play117, yet once again implicitly refers to the Magdalene’s womb, through a reference to the substance that so often is used to depict her vase-natural vasello.

By the end of the thirteenth century, her own discovered tomb, that is her container, in Provence was said to be made of alabaster, from which rose a fragrant odor like the alabastron of her gospel scene “filling the house”, hence leading to her identification118. Throughout the period of our investigation, the alabaster and its perfume are inseparably linked together and to the woman that bore them. A 1550 volume containing the recipes for hundreds of types of perfumed objects and perfumes contains one which claims to be the very scent that the Magdalene used over the feet of Christ. In a bizarre twist of what is in fact a kind of reproducible relic, the ingredients of the perfume include ground alabaster119. Here, container and content converge. The twist becomes that much more interesting in noting that the perfume was also considered a medicine for relieving ailments of the uterus.

This stone also hearkens back to Mary Magdalene’s first loci of iconographical development, the liturgical recipients of the paleo-Christian Mediterranean: sacred censers, containers of perfume such as ampullae; pyxes containing the Eucharist of the Christ who is “an oil poured out”, an apoteca. Hence, placing this object with its clear reference to the pyx in her hands functions as a sort of meta-iconography of the saint.

Glass

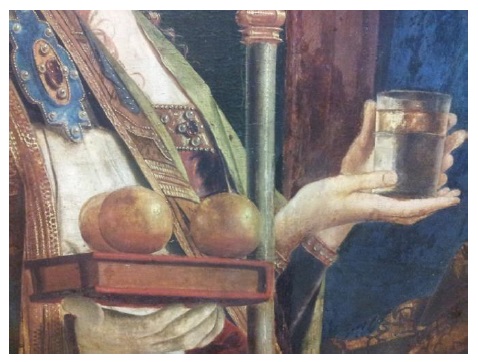

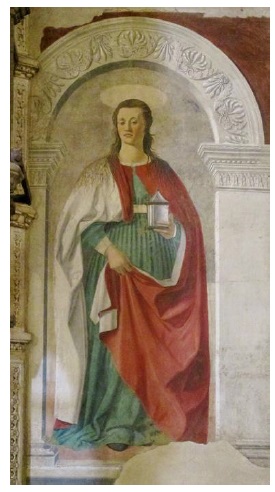

It is only toward the end of our period with the advent of oil painting that we begin to see a fully transparent vase in the Magdalene’s hands as in Sicilian Antonello da Messina’s rendering of the saint in his San Cassiano Altarpiece (Fig. 13), painted for Venetian patronage in 1476. Though a time-worn legend has this pala as bringing the art of oil painting to the lagoon and hence to Italian painting techniques, the reality is that oil had long been used, in some measure, as binding in the peninsula. In the course of the fifteenth century, however, there is more outright experimentation with the medium for its own specific properties120. One early user of a mix of oil and tempera was Piero della Francesca. It is no coincidence that it is his Magdalene painted in the 1450s and located in the Arezzo cathedral who is first given a translucent, if not transparent, vase (Fig. 14)121.

Fig. 13 Antonello da Messina, Pala San Cassiano, detail of vase, 1476, oil on wood, 115x135 cm (original work), Kunsthistorisches museum, Vienna (photo: Bsm15~commonswikii, Wikimedia Commons, in public domain).

Fig. 14 Piero della Francesca, Mary Magdalene,1450s, fresco, 190x105 cm, Duomo, Arezzo (photo: Dmitry Rozhkov, Wikimedia Commons, in public domain).

Immediately after Antonello’s pala, Giovanni Bellini paints an Anointing of Christ for his Coronation of the Virgin for the Franciscan church of Pesaro122. The jar is not strictly the Magdalene’s, as Bellini places it in the hands of Nicodemus, who also anointed Christ. It is however directly linked to her iconography through the long tradition of association between her and that object that we have seen laid out above. It is furthermore she who is in the act of anointing. Indeed, the vase seems, at least in Bellini’s image, to be a sort of shared identifier of the two. Bellini hides most of this container in the hands of the holy man, but the bits of rim that can be seen reveal effects of translucidity. Though Titian, the grand master of colorito alla veneziana, most often used alabaster for his Magdalenes, his 1560 figure of the saint also uses glass123.

Artistically speaking, it is no accident that this should come to pass in a Venetian orbit. Lagunary painting’s reputation had been built on the mimetic imitation of materials and textures, forming a strong divergence with Florentine values. By the fifteenth century the latter had sought to make an abstraction of support. It sought to make the viewer forget pigments, bindings, and wood panels so that the image should become, as in Alberti’s famous phrase, a window. The Serenissima’s glory however was built on the vast array of precious objects and substances coming through the Rialto, be it marble, marquetry, damasked silks, spices, or pigments. This helped to form a visual culture in which substance itself could be elevated to a meaningful role. Such works as Gentile da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi could function as a sort of manifesto of northern Italian visual values to Florentine eyes124. With the use of oil as medium, this same artistic culture sublimated the material investment into near perfect mimesis of surfaces and tactile values.

On another level, the appearance of a glass vase for the Magdalene occurring in a Venetian environment refers to their world-renowned achievements in glassmaking. The fiolarii of the Serenissima pushed themselves to ever greater feats of craftsmanship for the great collectors of Europe, princes who bought them as they bought paintings from famous artists125. The perfectly clear glass known as cristallo was a technical achievement of the mid-fifteenth century specific to the glassmakers of Venice126. Hence when Antonello presents the San Cassiano Altarpiece (Fig. 13) to the Venetian public, the Magdalene’s vase refers to the creative glory of the Republic’s visual tradition. The panel in fact, for much of modern understanding, was thought to be by the hand of Giovanni Bellini. It is a conscious choice of stylistic quotation for in much the same way Antonello was ingratiating himself as fully possible to his viewers, acclimating himself to their artistic value system.

The San Cassiano Altarpiece marks a turning point in Bellini’s career. Even if, like Piero della Francesca, he had long been experimenting with various proportions of oil in his tempera, it is from the appearance of Antonello’s work that he begins to exploit this medium to ever fuller extents127. Despite contemporary efforts toward transparency in the Tuscan context, such as with Verrocchio’s workshop’s masterful handling of tempera for the gauzy effects of drapery, only oil could hope to reproduce the perfectly crystalline effects of the vase pictured with Antonello’s Magdalene (Fig. 13), the limpid receptacle of Titian’s Hermitage Magdalene, Lucy’s vase of Bellini’s San Zaccharia Altarpiece, or the same in Sebastiano del Piombo’s pala for San Chrysostomo (Fig. 7). In these examples the delicate nuances of the oil medium permit the artist to show the viewer the contents of the vase as distinguished from the container, even where the liquid is itself pictured as a transparent oil. This can be the precious balsam in a fragile glass of a virgin like Lucy, or the perfume of the Bride, Christ’s name as oil poured forth, or nard of the anointing Magdalene. Since the Sermo placed the penitent mystic among the Virgins of the Apocalypse, any of these examples of its use with regard to the Magdalene easily includes all three.

The Venetian use of this material to embody the Magdalene’s vase, or Lucy’s, can be understood as a local cultural adaptation of the gold or the alabaster used in our previously examined works. Sebastiano del Piombo’s pala (Fig. 7) particularly seems to ask us to reflect in this sense when playing the Magdalene’s gold against Lucy’s glass. The two saints hold the precious vessels as if in parallel, as though we are to understand gold and glass as being equivalently exalted materials. Indeed, since Venantius Fortunatus (530-609) and even before, through to Alain de Lille (1128-1202/3) and beyond, glass has been used as a means of communicating the sacred nature of the Virgin Mary, indeed of explaining the post-partum virginity of the Mother of God128. Here the clear material is in the hands of the maiden saint Lucy, but conjugated in some sense with the Magdalene’s vessel, recalling again the Angelic Doctor’s equivalence of the two substances that we explored at the beginning of this article.

The glosses addressed in the paragraphs above, concerning Christ passing through stone as through Mary’s womb, build on the traditional association of Christ as the divine light passing through the Virgin’s hymen without breaking it while taking on its coloring, as we have seen in Venatius Fortunatus and Alain de Lille. This follows the paradigms of the gold and the alabaster-marble vases. The glass with its diaphanous properties can also point to the nature of the subtle body, which is said to surpass both gold and glass, as we have seen above with Thomas Aquinas129. Previous generations relied on the metal or the stone to convey those meanings, but the possibilities inherent in the oil medium, combined with the prestigious lagunary tradition of glassmaking, made way for this depiction of the Magdalene’s vessel. It is perhaps not a coincidence that in Venice the patron saint of the finestrieri was Mary Magdalene, as though this substance created of fiery metamorphosis from vulgar materials into something noble symbolized the essence of the saint, her propensity for taking the base matter of the sinful body and converting it through the fires of love into a sublimated substance130.

Indeed, the association of the saint with a vitreous substance can be, meaningfully applied to her in a way that surpasses the connotations of gold or alabaster-marble. The sand and potash that comprise its parts must undergo a particularly intense heat in order to produce it. As early as the latter twelfth century, the Italian visual imaginary depicted God creating Adam by means of a glassblower’s pipe131, a notion which will endure into the thirteenth century as seen in the Creation of Adam in the Palazzo del Cambio, Sala dei Notari, in Perugia132. In this we see once again the idea of the body as vessel, even if the metaphors of glass and clay are (perhaps knowingly) mixed. Glass and terracotta both undergo the chemical change that creates them by means of a kiln. Glass however required a more specialized use of heat than does pottery, so much so that thirteenth century Italians did not have the native means to produce it in great quantity. The Magdalene’s conversion was essentially conceived of in terms of such heat133. From Gregory the Great to Bonaventure and beyond it is a great fire of love that burns in the Magdalene provoking an essential change in substance through a phase of liquefaction134. As Iohannis de Castello puts it “Magdalene was placed in the furnace of love, to be melted and to take the form of a new vase”135. For Gregory this change is from impurity to gold. But in terms of the body, we know, gold and glass are conceived of as belonging to one family. Only glass though could suitably convey a sense of molten combustion of impurities into a substance of perfect limpidity which could, as did the illuminata-illumniatrix, receive and reflect light.

The Vase and Its Form in Artistic Representation

The Vase as Liturgical Vessel

As with the material chosen to associate with the Magdalene’s vase, its form is no less invested with meaning. This extends to the form’s compositional ends that the artist cultivates within his creation.

The Pisan Cross (Fig. 8), Guido da Siena (Fig. 1), and the Magdalene Master (Fig. 9) all use not only the material of liturgical vessels but also the form. These thirteenth century artists usher in a usage that will be continued throughout the following two centuries. Nearly all the examples studied here use some form of sacred vase to give shape to the perfume jar, up through to Fra Bartolommeo’s 1504 God the Father with Magdalene and Catherine of Sienna.

The Magdalene Master’s 1285 usage is particularly sophisticated (Fig. 9). The pointed cylindrical shape in the hands of the saint echo the two towers that frame her standing figure. “Magdalene”, since Jerome’s etymology, was commonly understood to mean “tower”136. This was then, like the reflective substance of the receptacle, a reference to the meaning of her name. The artist also frames the main iconic figure’s head with a tower on each side, underscoring this intention. Yet still, these pointed cylinders, especially as placed near the top of the panel, repeat the form of the pala itself. It then imitates in substance as well as form the perfume jar of the preaching scene. Panel and vase become synonymous with each other. Furthermore, like the towers, they refer to the Magdalene’s name and to her theological function by their lustrous substance. As the Magdalene “absorbs” the pictorial surface of the panel137, she becomes identical to it. The meaning could not be made clear without the exceptional attention given to the vase’s shape, perhaps inspired by the formal echoes between vase and dossal seen in Guido’s work (Fig. 1). It is possible to see a comparable notion in the Magdalene depicted in the niche of the Lion Polyptych (Fig. 3). The vase is placed in such a way as to encourage the viewer to note the formal echo with the niches sculpted into the interstices of the frame in another kind of early mise-en-abyme.

This formal sleight of hand creates a tautological relationship between the saint and the shape of the vase, just as artists had done with its substance. Antonio Venziano’s bust figure of the Magdalene is one example. Her mantle is fastened at the neck to fall over her robe. This becomes an outline of gold tracery in the form of an open triangle. It is in fact a simple transposition of the shape of her ointment jar, the fastener echoing the node of the vase’s lid (Fig. 10). The bust figure of Paolo Veneziano in the Chioggia predella is another early example. We see a similar idea in the frescoes of Subiaco when the angel announces the Resurrection to the Magdalene138. In the middle of the fifteenth century, Piero della Francesca’s Magdalene builds on this idea (Fig. 14). Her mantle falls in the same manner, echoing the lid of the crystal vase. Yet Piero goes further. His fundamentally volumetric mind brings the body of the saint into an even stronger equivalence with the cylinder she holds. Other examples include the elongated profiles of saint and vase in Carlo Crivelli’s Montefiore Magdalene (Fig. 12). The Magdalene of Raphael’s Ecstasy of Saint Cecilia takes the same principle of profile but integrating the use of the curves of her figure with those of the ewer form given to the vessel. This later piece is a prime example of the use artists made of Firenzuola’s Dialogo on the female body as vase discussed above.

The form of the vase and the female pudenda

Whereas the above examples trace an equivalence between the body of the Magdalene and her vase, this symbolism can also be more pointed still. We saw in the exposition of this article that the vase can also be, in Dante’s expression, the natural vasello of the female sexual organs. This is clear when we see her holding her vase, surrounded, as with the Raphael, by Paul, John, and Augustine, who were all renowned for their virginity or continence.

It is tempting to apply a similar reading to Piero’s Magdalene (Fig. 14) when viewed in conjunction with the Madonna del Parto139, for instance. Her framing drapery takes up a comparable triangular line where her body also takes the form of a cylinder, the evocative opening of her robe in largely the same zone as the crystal vase. The Polyptych of the Misericordia140 encourages this connection when the Magdalene’s vase, as painted in Giuliano Amidei’s predella, is once more lidded by the cone with node largely retraced by the Madonna’s cloak in the principal panel141. Vase and vasello seem to coincide.

The vase was held at heart level by the Magdalenes of Guido da Siena (Fig. 1), the Magdalene Master (Fig. 9), and Paolo Veneziano, but afterward slid to a lower level. It is not an absolute shift. The vase is still often held at the level of the heart, for example, by the two standing Magdalenes of Carlo Crivelli (Fig. 11), bringing to bear the heart - a kind of womb as we now know - as vase in which the unguent is fabricated from her tears. As noted previously we find this described as early as Bernard of Clairvaux (1091-1153) in his sermons on the Song of Songs and as late as Savonarola (1452-1498) in his Miserere142. Still, Pietro Lorenzetti and Andrea di Bonaiuto lower the vase to place it between breast and belly, implying a stronger connection with the womb. We see this again in the Lion Polyptych (Fig. 3) and the Cortona Tryptych, for instance. This is nowhere clearer than in the Magdalene attributed to Biagio d’Antonio in which the triangular lines of the vase’s conical lid are repeated in the parting of the hair over the thigh as well as in the inverted triangle of hair meeting between her legs immediately below it. During this same period, the Magdalene’s perfume jar was used as the emblem of the Florentine convent of Santa Elisabetta for converted prostitutes143. It referred certainly to the means of conversion and forgiveness of their patron saint, but also structurally to the means by which she sinned carnally in the first place.

For the latter part of our period the early modern era, although more daring in depictions of the eroticized female body, the genitals remain taboo. “Yet her own sex is a generalized nullity; her own body offers ‘nothing you can see’ - and what you might see is displaced onto or into that essential shell,” writes Rona Goffen on Titian’s Edinburgh Venus c. 1520. The remark, paraphrasing Lucie Irigaray, also applies to many other depictions of female nudes144.

This kind of displacement of symbolism is a visual convention much opposed to the earlier theological fascination with Mary’s reproductive mechanics, as Georges Didi-Huberman has shown145. On another tack, it can also apply to the fascination with the anatomy of the Pythia. Origen (c. 184-c. 253) explains the impure nature of her prophecy since the vapors that inspire her penetrate her genitals to produce words from her mouth as Giulia Sissa so pertinently remarks146.

Between the forbidden representation of the pudenda in western art, and the obsessive preoccupation with the same in Christian theology, the Magdalene’s vase allowed for a visual means for conveying a sacredness to and of female sexual organs, even those who have experienced carnal knowledge. That meaning has been largely lost to present viewers but may well have been a reflexively and largely understood sense for the various inflections of the period gaze. Spectators of course varied, then as now, in education levels and engagement. Too, the contexts and placement of each piece are also specific to the painting in question. Sadly, that the space allotted here does not allow for exploring as each deserves147.

Concluding remarks

Be that as it may with regard to the specificity of the body part, the vase as synecdoche of the Magdalene’s body was inescapable, through form or substance, in the imaginary of the spectators and the artists at least at some level. We can also look at other depictions of the saint in this way. By the time of Giotto’s early Trecento Assisi Crucifixion, the Magdalene is placed at the foot of the cross in complement to the angels placed at Christ’s hands and side148. These hold recipients with which to catch the Holy Blood. The feet do not have a corresponding angel, only the saint whose mouth is close to the wound. Recipient herself, she becomes a container of Christ’s blood, recalling the use of the image of the cup in reference to her role in the Resurrection. Her red cloak reinforces this interpretation. A few decades later Simone Martini pictures the Magdalene’s head in profile against the wood of the cross, as the blood streams into her open lips149. This enormously popular formula insists once more on her role as vessel of Christ, ushered in by Guido da Siena or even by the liturgical vases of the paleo-Christian era. It is in this sense that we must view the Magdalenes - such as that of Paolo of Veneziano (Fig. 15) - portrayed as containing the image of Christ in her heart. The small portrait of Christ in her heart, surrounded by a genitally evocative pair of tresses, surprises modern eyes which ascribe this clipeus exclusively to the Virgin. It is however quite in keeping with her role as liturgical vessel, receptacle of the sacramental fluids of the Incarnate God’s body.

Fig. 15 Paolo Veneziano, Mary Magdalene in ecstasy with clipeus, detail of Virgin and Child, portable tripych with Crucifixion, ca. 1335, 74,5,x75 (original work), Galleria Nazionale, Parma (photo Sailko, Wikimedia Commons, in public domain).

It is entirely comparable to her role as she who receives Christ’s radiating light to overflow in offering it to others. In this she is that other container, the mystical body of Christ, the Ecclesia, hence too the Bride and the Creature, the Soul. The vase, through her founding act of conversion, that is the anointing of the Anointed One, is the intimate means by which she becomes initiate of the Flesh of the Word, the mystery of the Incarnation. The vase, with which the Magdalene anointed the Christ for his sacrifice as if by premonition, also conveys the hollowness of the female body that explains her prophetic role. A structural corollary of Christ’s wounds, it is also a sacramental container, giving the woman who handles it a sacerdotal role.

A stand-in for the genitals, the womb, the heart, or the whole female organism, the vase must be considered as a tautology for the figure of Mary Magdalene. Woman was container. Mary Magdalene, daughter of Eve, carnal sinner, was certainly overflowing with the bodily humors of hair and tears. With her conversion however, her transgressive body changed in nature if not in its fundamental function, in its final cause of receiving and containing and pouring. In the hands of artists from the thirteenth century to the sixteenth, the Magdalene’s body, as conveyed by the vase she holds, changes Eve’s instrument of perdition to sanctified liturgical vessel in both form and substance.