To evoke the castle of Belvoir or any Frankish fortification in the Holy Land through textual sources, we must begin by sequencing, presenting and commenting on the data in strictly chronological order. However, this process calls for a preliminary warning: To do a critical analysis, two elements must be kept in mind: pattern and nature.

1132, 1165, 1168, 1169, 1182, 1188, 1212, 1219 and 1239, what can we say about the pattern of this sequence? Like snapshots taken with a phosphorus flashlight, these dates shed light on a few special, privileged moments in the castle’s history. Only nine dates over a 107-year period (1132-1239), a chronological interval that corresponds to the history of the site in light of written sources, a subset that fits into a wider period, the Frankish presence in the Holy Land (1099-1291).

The nature, the content of these data is somewhat redundant. As we hear the clash of arms while reading the chronicles and accounts of the conflicts between Franks and Arabs, Christians and Muslims, conquerors and defenders, allogenous and indigenous populations, we notice that these sources examine almost exclusively the military role of the castle. They mention the quality of Belvoir’s geographic and topographic position “in loco sublimi”1 or, to quote Le Toron, “quoniam in monte erat excelso admodum et cacuminato”2 or, according to Safed, the solidity of its walls: “castrum munitissimum”3 and the architectural genius of these defense elements: “que in inmensibus sub terra profunde inter antemuralia et fossata cum crotis…, que dicuntur fortie cooperte”4, etc. But, away from the echoes of the battles recorded in these chronicles, another aspect of the functions of a crusader castle in the Holy Land emerges from the silence and the everydayness of seemingly trivial notarial deeds, sales, exchanges and transactions. These economic and administrative activities do not replace security concerns, they complement them.

From one village to another

Location and establishment

Geographically, the Belvoir site is located a dozen kilometers from the southern limit of Lake Tiberias, 25 km south of the city of Tiberias, and about 12 km north of the city of Beit She'an, the ancient the ancient Scytopolis and the crusader Beisan.

Topographically, the castle is on the right bank of the Jordan River, on the western slope, at an altitude of about 300 meters above sea level, on the edge of the top part and eastern border of a basaltic plateau, overlooking a steep slope to the east towards the valley of the Jordan and to the north towards the Nahal Tavor River. From this elevated point we can see Mount Thabor to the northwest, Lake Tiberias to the north, then from the northeast to the southeast, the Golan Heights, the Yarmouk Valley and the north of present-day Jordan, together referred to as the "Terre de Suète" (al-Sawad) at the time of the Crusades (Fig. 1).

Below the remains of the castle, the ruins of an ancient settlement, still visible today, surround a spring, which has been refurbished at various times. This primitive settlement dates back to at least the end of the period of the second temple and could correspond, according to various sources, particularly from reading the Talmud, either to the village of Aggripina or Gropina, or to that of Cochaba5. The settlement was still occupied by a Jewish community during the Byzantine era, as evidenced by a synagogue whose spolia were integrated into the architecture of the castle. However, it died out sometime after the Arab conquest. Initially named Cochav, meaning “star” in Hebrew, it was renamed Kawkab, its Arabic translation, after the Muslim conquest. Not knowing the meaning but retaining the sound, the Franks who occupied Galilee and settled there at the dawn of the twelfth century transformed Kawkab into Coquet (Coket), a term clearly justified by the charming vistas the site offers.

From village to Castle ...

A mention of Coquet first appears in Frankish sources in a 1165 charter from the Prince of Galilee, Walter of Tiberias, that confirms the donation to the Holy Sepulcher of two Galilean villages, Gebul and Helkar. The charter indicates that their northern boundary extended to Casal Coket. One of the witnesses to sign the act was a man named Ivo6. This confirmation reflects the wording of an older deed, the 1132 donation of the casals of Gebul and Helkar by William of Bures to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher7. However, while this deed gives an identical description of the environment of these casals to the confirmation of 1165, it makes no mention of casal Cocket and the document is not signed by Ivo. This allows for the following assumptions: we must consider that the village of Coquet was created between 1132 and 1165.

At a time when the Latin kingdom was still expanding, a new village in this part of the Principality of Galilee could only have been created by the Franks. So, the question of its population remains: Frankish settlers, Oriental Christians or both?

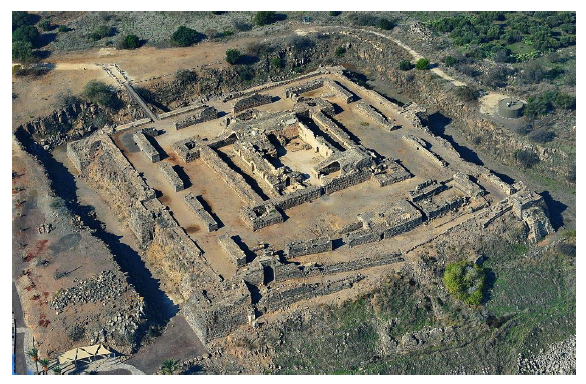

In 1168, an act from the Prince of Galilee confirms the ownership of a castle by the Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem in a domain sold to them by a Frank named Ivo Velos8 (see this volume article by Damien Carraz on the role of the Hospitallers in the history of Belvoir). The mention of a “castrum de Coquet quod vulgariter Belvear nuncupatur” 9 clearly attests to the erection of a new castle, called Belvoir10, on the site of the village previously mentioned in the act of 1165 (Fig. 2). The name of Belvoir undoubtedly takes its origin from the fantastic vista from this point of the plateau dominating the valley of Tabor, the Lake of Tiberias and the valley of the Jordan (Fig. 3). Although the fact that “Casal Coket” had been renamed “Castrum de Coquet” could suggest that the village was already fortified, the construction of the concentric castle, whose remains are still visible today, is attributed to the Order of Hospital. This design, with a double quadrangular enclosure separated by an endless hall and flanked by quadrangular towers, was first built, by the Hospitallers at Beth Guvrin (the Frankish “Gybelin”), in several phases, starting in 113611 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2 Remains of a building dating from the 12th century (village of Coquet) prior to the hospital castle and discovered in the courtyard of the latter (© Simon Dorso).

Fig. 4 Aerial view of Belvoir Castle. (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belvoir_Castle_(Israel)).

There are sources to confirm the relative contemporaneity of the erection of the castle and the Act of 1168. Even if he doesn’t mention it by name, there is no doubt that Theodericus refers to it when he mentions around 1169: “In cuius vicino monte precelso Hospitarii fortissimum et amplissimum castrum”, a fortified place that he associates with the Templar possessions of Safed and La Fève as defenses of Galilee12. In his account of Baldwin IV’s military campaigns in 1182, William of Tyre, recounting that he had to provide a contingent to join the army regrouping in Tiberias, like in Safed and other fortresses, mentions a “castrum novum cui nomen est hodie Belveir “13 and still considers it a recent construction14.

Belvoir becomes Kawkab again

A year and a half after the rout of the Frankish army at the Horns of Hattin, Belvoir Castle was still in the hands of the Hospitallers. A letter sent in January 1188 by Thierry, former grand preceptor of the Order of the Temple to Henry II, King of England, announcing the loss of Jerusalem and establishing a state of the Holy Land still mentioned “Belliverium a fratibus Hospitalis egregie defensum”15 among the possessions of the kingdom16. In another letter, also dated January 1188, addressed to the King of Hungary the Count Conrad of Montferrat mentioned Belveder among the places still defended17.

However, the Muslims had fairly quickly put in place the preparations for the siege. According to Ibn al-Athῑr, Saladin had already sent two detachments to isolate Belvoir and Safed when he was still on his way to Ashkelon. This would indicate that the preparations for the siege took place in August 118718. On January 2, 1188 the Frankish garrison made a sortie and beat the Muslim troops near Forbelet, killing their commander, Sayf al-Din Mahmud. In the first ten days of the month of Muharram 583 AH (March 3 to 13, 1188), Saladin came in person to lay siege with his troops. In November 1188, in a letter addressed to Duke Leopold V of Austria, Armengaud of Aps, Master of the Order of Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem, expressed his fear about the fate of the castle, of which he had no news19. On 15 Dhu al-qa'da 584 AH (January 5, 1189), approximately one month after the fall of Safed, Belvoir surrendered for lack of provisions. Its defenders, according to al-Harawῑ, had to resign themselves to “leaving it, coming out of it humiliated and handing it over because salt was lacking”. For Ibn al-Athῑr, the undermining of the barbican is what led the garrison to negotiate surrender. The agreement concluded with Saladin allowed the occupants of the castle to reach Tyre safe and sound20.

In the spring of 1192 (588 AH) Saladin, faced with the Third Crusade, sent his brother al-ʿĀdil to seek reinforcements in Kawkab (Belvoir) and in the Jordan Valley (Ghor). On October 19, 1192 (10 Chawwal 588 AH), Saladin was in Kawkab and, having examined the state of the fortress, ordered repairs21.

In 608 AH (1211-1212), Malik al-Mu'azzam 'Īsā had his lord, the emir ʿIzz al-Dīn Usāma, arrested for fomenting a revolt, and ordered Kawkab castle to be dismantled22.

A Frankish reoccupation in the thirteenth century?

In 1219, faced with the siege of Damietta led by John of Brienne as part of the Fifth Crusade, Sultan al-Malik al-Kāmil initiated negotiations to obtain the evacuation of Egypt by Frankish troops. He proposed a truce of 30 years and the restitution of certain places including Jerusalem, Safed and Belvoir. Pressured by the Legate Pelagio Galvani and the Templars, the Franks refused23.

A Latin text enumerating the Muslim possessions in the kingdom of Jerusalem around 1239 does mention Belvoir: “Item castrum quod Bellum videre dicitur, et fuit Jherosolimitani Hospitalis”24.

In the summer of 1240, after an agreement between Theobald IV of Champagne and Richard of Cornwall on one side and the Emir of Damascus, As-Salih Ismail on the other, the Franks recovered some of their former possessions, including Belvoir25.

No sources mention a restoration of the fortifications of the castle, but an agreement signed on October 25, 1259 by Hugues Revel, master of the order and Henry, archbishop of Nazareth, about a dispute relating to the payment of the tithes of Belvoir and its outbuildings unambiguously attests to the return of the Hospitallers to their domain, which would henceforth appear as an advanced enclave in Ayyubid territory26. However, by 1247 most of the territories affected by this treaty had been reclaimed by As-Salih Ismail, who considered that Louis IX's crusade violated the terms of the agreement. An army led by Emir Fakhr al-Dῑn ibn al-Shaykh had recaptured Tiberias in June 1247 and the fortress of Mount Tabor soon after27.

The date the castle returned to Muslim hands is not known, but a treaty signed in 1283 between the Mamluk Sultan Qalāwūn and the Frankish authorities in the city of Acre stipulated that Kawkab was indeed on Muslim land28. At the same time (between 1283 and 1285) Burchard of Mount Sion mentions Castrum Belveir29.

No Mamluk sources mention the site, although a Khan was built below the castle, facing the bridge crossing the Jordan in the fourteenth century.

From Castle to village

A mention of the village, by then occupied by hovels, is found in an Ottoman tax statement dated 1596, under the name Kawkab al-Hawa (the star of the winds). It was part of the district of Lajjun, and its 50 inhabitants paid taxes on their harvest of wheat, beans, melons and vines30. In 1859, the village population, still contained within the perimeter of the castle walls, was estimated at 110 souls by Consul Roger31.

With 46 houses in 1931 and an estimated population of 300 in 1945, the village of Kawkab al-Hawa was depopulated after it was attacked by the Haganah between May 16 and May 21, 194832.

Functions of Belvoir Castle under Frankish domination

The military role of Belvoir Castle: Fulk of Anjou or the “Vitry Line” before Maginot

Jacques de Vitry mentions Belvoir and a number of other castles in Historia Orientalis, a text he composed between 1216 and 1227, when he was Bishop of Acre. The text is anachronistic and too often mentioned without critical analysis, which leads to two errors. The first one concerns the dating of the construction of the castle, the second one its motivations. Here is the original text in Latin followed by its translation:

“Cum igitur ciuitates memoratas pluresque alias, maxime mediterraneas, nostri subiugare non possent, in extremitatibus terrae suae, vt fines suos defenderent, castra munitissima & inexpugnabilia inter ipsos & hostes extruxerunt, scilicet Montem Regalem, & Petram Deserti, cuius nomen modernum est Crac, vltra Iordanem, Sapheth & Belvoir, cum multis aliis munitionibus, citra Iordanem. Est autem Sapheth castrum munitissimum inter Accon & mare Galileæ, non longe a montibus Gelboë situm. Belvoir vero, non longe a monte Thabor iuxta civitatem quondam egregiam & populosam Iezraël, inter Citopolim & Tyberiadem, situm est in loco sublimi”33.

“So our people, not having been able to conquer the cities of which I have just spoken and several others, and mainly the cities located in the interior of the lands, and wanting to defend their borders, built at the end of the territory they occupied, and consequently between themselves and their enemies, very strong and entirely impregnable castles, namely, beyond the Jordan, Mont-Réal and the Stone of the Desert, whose modern name is Crac, not to mention many other fortresses. Saphet, a very strong castle, is located between Accon [Acre] and the Sea of Galilee, not far from the mountains of Gilboa. Belvoir is located on a very high point, not far from Mount Tabor, next to the city of Jezreel, which was once very beautiful and very populated, between Scythopolis [Beit She'an] and Tiberias” 34.

In his chronological account, Marino Sanudo included this passage almost word for word at the end of the reign of King Fulk, which was in 1143 at the latest35. Max van Berchem had already contradicted Guérin and his immediate successors when he pointed out that Jacques de Vitry had not mentioned any dates for the construction of the various castles mentioned in this passage36. Moreover, Jacques de Vitry contradicted himself when he mentioned a construction campaign planned under Fulk’s reign. He had previously dated in his chronicle the erection of the castle of Montreal over the River Jordan in the same year as the death of King Baldwin I, which was in 111837. Actually, the passage quoted here appears in Jacques de Vitry's account after his description of the failure of an Egyptian campaign attributed to King Amalric. Between 1163 and 1169, Amalric led five campaigns against Egypt. Jacques de Vitry's account clearly refers to the fifth campaign (Oct. - Dec. 1169)38. However, by that time the Belvoir site had already been passed on to the Hospitallers and the construction work of the concentric castle had clearly started - and had probably already been finished, as a mention from Theodericus around 1169 suggests (see above).

Paul Deschamps wrote that the importance of Safed's position must have been quickly recognized by Hugh of Saint-Omer. Basing his arguments on no archaeological data or original sources other than Vitry's, he considered it “probable” (sic) that King Fulk fortified Belvoir and Safed. It is clear that this hypothesis has since been adopted, and still is today, by many researchers. In Safed, Arab sources mention a first fortification as early as 1102, therefore contradicting the suggestion that the castle was erected under Fulk’s reign.

Chronological issues aside, the function of the castles remains, according to Deschamps, almost exclusively defensive. On this, the subtitle of the second volume of his study of crusader castles in the Holy Land, “La défense du Royaume de Jérusalem” is more than evocative.

To better understand Deschamps, we must consider the mentalities of his time, the interwar years. From a military point of view, the twenties and thirties were marked by the preponderance of a defensive strategy. Between 1927 and 1929, Deschamps had studied and partly excavated the Crac des Chevaliers with the help of the French Army of the Levant. The environment in which he evolved must have constituted a fertile ground for him to take up the hypothesis, already put forward by Rey, of a reasoned development of fortified lines to defend the borders of the crusader states of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries39. Vauban and Maginot, “spiritual sons” of Fulk of Anjou…

While the geographical and topographical position of Belvoir undoubtedly gives strategic value to the place, it is necessary to situate its construction in the context of the time, Amalric’s reign. Even though the campaigns that were carried out at the time were unsuccessful, in Egypt in particular, they clearly show that the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem was still behaving as an offensive state seeking to expand. It is therefore necessary to look for reasons, beyond military ones, that could justify for the order of the Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem to invest colossal sums in the construction of the castle of Belvoir.

The Castle of Belvoir as a tool for the management and colonization of a territory: the Castellany of Belvoir

The various transactions that appear in many deeds attest to the acquisition by the Hospitallers of villages and their land around Belvoir. Their distribution clearly shows a territorial grouping. The acquisition dates prove that the domain began forming well before the construction of the castle. No longer a mere border post, it appears as the center of an administrative and economic power, a central part of the management of a territory.

Excavations in the castle have, for example, made it possible to discover a number of fragments of sugar molds40. The sugar cane plantations and production workshops being located not on the plateau but in the valley, the presence of these utensils in the castle can only be explained by their storage and their grouping in one place from which they could be dispatched to the production centers of the Belvoir castellany.

Conclusions

In the light of available written and archaeological sources, the functions of the Frankish castle in the Holy Land are more diversified and clearer. The castle is indeed a place of military assembly from which contingents are summoned to join the ost. It constitutes a place of refuge, it can be called to support sieges, or be the point of departure of a rescue army. These various events attest the punctuality of its strategic function. On the other hand, its occupants had to carry out the various daily tasks necessary for the good management of the domain placed under the dependence of the castle. If the study of the deeds of acquisition makes it possible to define the limits of this territory and the number of villages attached to it, it is more difficult to know its populations. As for Horvat Shema41, reoccupied during the Frankish period in the castellany of Safed, the village of Coquet, created in the second third of the twelfth century, must have welcomed a Christian population, probably a mixture of Eastern Christians and Frankish settlers.

Already carried out on the castle of Safed42, studies of a territory dependent on a castle clarify the importance of the economic role of these fortified centers in the Latin East.

Bibliographical References

Printed Sources

ABU’L-FIDA, Isma’il - “Résumé de l’Histoire des Croisades tiré des annales d’Abu ’l-Fida“. In Recueil des historiens des Croisades publié par les soins de l'Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres. Historiens orientaux. Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1872, t. I, pp. 1-165.

ABU SHAMA - Kitab al-Raudatayn fi Akhbar al-Daulatayn. Ed. M. H. M. Ahmad an M. M. Ziyada, Cairo, 1956-1962, 2 vols.

ABŪ SHĀMA - “Le livre des deux jardins”. In Recueil des historiens des croisades publié par les soins de l'Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres. Historiens orientaux. T. IV. Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1898.

BAHA’ AD-DIN IBN SHADDAD - “Anecdotes et beaux traits de la vie du sultan Youssof (Salah ed-Din)“. In Recueil des historiens des Croisades publié par les soins de l'Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres. Historiens orientaux. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. T. III, 1866.

BURCHARD DE MONT-SION - Peregrinatores medii aevi quatuor: Burchardus de Monte Sion, Ricoldus de Monte Crucis, Odoricus de Foro Julii, Wilbrandus de Oldenborg... Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs, 1864.

Cartulaire de l’église du Saint-Sépulcre de Jérusalem publié d’après les manuscrits du Vatican. Ed. E. de Rozière. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1849.

Cartulaire général de l'ordre des Hospitaliers de St.-Jean de Jérusalem (1100-1310). Ed. J. Delaville Le Roulx, 4 vols. Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1894-1906.

GUILLAUME DE TYR- “La continuation de Guillaume de Tyr, de 1184 à 1261”. In BEUGNOT, Arthur; LANGLOIS, A. (ed.) - Recueil des historiens des Croisades publié par les soins de l'Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettre. Historiens occidentaux. Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres, 1859, t. II.

GUILLAUME DE TYR - “L'Estoire de Eracles, empereur, et la conqueste de la Terre d'Outre-Mer, c'est la continuation de «l'Estoire» de Guillaume, arcevesque de Sur: Continuation de Guillaume de Tyr, de 1229 à 1261, dite du manuscrit de Rothelin”. In BEUGNOT, Arthur; LANGLOIS, A. (pub.) - Recueil des historiens des Croisades publié par les soins de l'Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres. Historiens occidentaux. Paris: Impr. royale, 1859, t. II, p. 1-481.

GUILLAUME DE TYR - Willelmi Tyrensis archiepiscopi Chronicon. Éd. R.B.C. Huygens, Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 63-63a, Turnhout: Brepols, 1986.

GUILLAUME DE TYR - Chronique du royaume franc de Jérusalem de 1095 à 1184. Traduction G. et R. Métais, 2 vol. Paris: L’Intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux, 1999.

HUYGENS, R.B.C. - De constructione castri Saphet, Construction et fonctions d’un château fort franc en Terre-Sainte. Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1981.

IBN AL-ATHIR - “Extrait de la chronique intitulée Kamel - Altevarykh“. In Recueil des historiens des Croisades publié par les soins de l'Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettre. Historiens orientaux. Paris: Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, 1844, 1859, t. I, pp. 187-744; t. II, pp. 3-180.

IBN SHADDAD AL-HALIBI - al-A’laq al-Khatīra fi Dhikr Umarā’ al-Shām wa’l-Jazīr. II, pt. 2, Tārῑkh Lubnān, al-Urdunn wa-Filastin. Ed. S. al-Dahhān. Damascus: Institut Francais de Damas, 1963.

La chronique d’Ernoul et de Bernard le Trésorier. Ed. L. de Mas Latrie. Paris: Vve de J. Renouard, 1871.

Les Gestes des Chiprois. Recueil de chroniques françaises écrites en Orient aux XIII e et XIV e siècle (Philippe de Navarre et Gérard de Monréal). Ed. G. Raynaud. Genève: Fick (Publications de la Société de l'Orient latin. Série historique, 5), 1887.

“Les Gestes des Chiprois“. In PARIS, Gaston; LATRIE, Louis de Mas (éd.) - Recueil des historiens des croisades publié par les soins de l'Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettre. Documents arméniens. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1906, t. II.

MAQRĪZĪ, Aḥmad ibn ʻAlī, - Histoire des sultans mamlouks de l’Égypte. Trad. M. Quatremère Paris: [Firmin Didot Printed for the Oriental translation fund of Great Britain and Ireland; J. Valpy and B. Duprat], 1845, 2 vols.

PAOLI, Sebastiano - Codice diplomatico del sacro militare ordine Gerosolimitano oggi di Malta: Raccolto da vari documi. T. I. Lucca: Marescandoli, 1733.

RÖRICHT (comp.) - Regesta regni Hierosolymitani, 1097-1291. Oeniponti, Libraria Academica Wageriana, 1893. Additamentum 1904.

SANUDO, Marino - Secreta Fidelium Crucis. Ed. Bongars, Gesta Dei per Francos. Hanover: Wechelian, 1611.

SOURDEL-THOMINE, Janine (ed.) - “Les conseils du Sayh al-Harawῑ à un prince ayyūbide”. Bulletin d’études orientales XVII (1961-1962) (extrait).

THEÓDORIC - Theodericus Libellus de Locis Sanctis. Eds. M. L. et W. Bulst. Heidelberg: Winter, 1976.

THEÓDORIC; SAEWULF; JOHN OF WÜRZBURG -Theodericus, Peregrinationes tres: Saewulf, John of Würzburg. Ed. R. B. C. Huygens, with a study of the voyage of Seawulf by J. H. Pryor. Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio Mediaevalis 139. Turnhout: Brepols, 1994-1995.

JACQUES DE VITRY - Iacobi de Vitriaco, Primum Acconensis…., Libri Dvo, Quorom prior Orientalis, Sine Hierosolymitanæ: Alter, Occidentalis. Ed. F. Moschus. Duaci: Ex officina typographia B. Belleri, 1597.

JACQUES DE VITRY - Historia Orientalis seu Hierosolymitana, Ed. J. Bongars, Gesta Dei Francos. I: 1047-1145. Hanau, 1611.

JACQUES DE VITRY - Histoire de l’Orient et des croisades pour Jérusalem. Trad. F. Guizot. Ed. N. Desgrugillers. Clermont-Ferrand: Éditions Paleo, 2005.

Willelmi Tyrensis archiepiscopi Chronicon. Ed. R.B.C. Huygens. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis, 63-63ª. Turnhout: Brepols, 1986.