The previous paper showed that a settlement prior to the castle is mentioned three times in twelfth-century Latin documentation. The nature of the settlement is uncertain, as it is designated as casal, a very common term in many Latin areas around the Mediterranean (Italy, Sicily, Cyprus, Frankish Morea, Syria) between the twelfth and the fourteenth centuries. Depending on the time and place, it covers different realities. In Frankish Palestine, a casal seems to be the most frequently mentioned form of rural grouped settlement found in the charters. However, the size of the site in question, of its population and its economic or legal status may vary considerably1. For their part, the terms burgus and castrum, also used to designate village sites, tend to underline the fortified character of a site or its possibility of defense2. We have also seen that the name of the casal we are interested in here was not entirely unrelated to the historical substrate of the area, since the toponym Cocquet probably derives from the Arabic name Kawkab, which descends from the Hebraic name Kokhava. Does the persistence, in a barely corrupted form, of the ancient toponym up to the Middle Ages underpin an uninterrupted occupation of the site? Perhaps the existence of important ruins and material remains were enough to preserve the memory of its name? It is difficult to tell from our sole sources.

An important point also mentioned is the chronology of the occupation of the site. If we look solely at the written sources available to us, the first mention of Cocquet in Medieval times appears in two Latin charters issued by Walter, prince of Galilee, in 1165. These documents establish the boundaries of the casal of Gibul, specifying that it meets Casal Cocquet to the North (ad aquilonem)3. The first document, whose dating is essentially based on the identical list of witnesses, settles an argument over ownership of the casal. Both charters also mention the casal’s western boundaries with the casals of Hubelet, Dersoet, Derlauha and Kafra4. If the casals of Dersoet and Derlauha have not been identified in a satisfactory manner, those of Hubelet (Yubla) and Kafra (Kafra) leave no doubt regarding the identification of Cocquet with Kawkab. Thus, a twelfth century map of the villages strongly resembles a map drawn in the first half of the twentieth century by British commissioners in Palestine. While these documents allow for the location of Cocquet, they raise another question: why is it not mentioned in earlier documents whereas the casal of Gibul appears in three earlier charters along with the casal of Helkar? The first charter, dated 1132, mentions its donation by William of Bures to the Holy Sepulchre, along with the casal of Helkar5. The only geographical information given by the document is that both casals are located on the edge of the lordships of Bethsan and Tiberias, alongside mountains bordering the Jordan Valley, to a cave located near a casal called Huxenia. This information is reused in one of the acts from 11656. The next two acts, dated July 1155 and 1160, are confirmations from King Baldwin III of donations to the priory of the Holy Sepulchre; they obviously draw on earlier documents previous acts kept by the royal chancellery7.

This raises the question of the scope of the differences between the acts of 1132 and those of 1165. The first deed mentions only one casal, Huxenia (this is the only mention of the site), whereas the later documents turn to the north and the Issachar plateau. It delineates the lands of Gibul from four casals. How to interpret this change in the description, when acts are generally very codified, compiling, even quoting word for word, the previous documents from which they are established? Two main hypotheses could be formulated. The first one involves the documentation through the context and places of its production, assuming that the author and the destination of the document condition its content and the accuracy of its information. The act of 1132 was issued by the Chancellery of the Principality of Tiberias and concerns a donation from the prince, a legal authority with detailed knowledge of the territory in question, while the acts of 1155 and 1160 consist in two long royal confirmations of all the priory’s property in the kingdom which were probably established from all the charters preserved in Jerusalem, both in the Royal Chancellery and in the priory’s archives. The 1165 acts redrafted in Tiberias would, as before, show a better knowledge of the concerned area and an immediate interest in its division and organization. One of the documents explicitly refers to an on-site investigation to settle the dispute over the ownership of the village and involving several credible witnesses8. The information contained in the acts would therefore depend on the purpose of the document (one-off confirmation or settlement of dispute).

In the second hypothesis, perhaps less supported, the late appearance of Casal Cocquet in the sources could be explained by the fact that it was not occupied in 1132 or that it was not worth being mentioned. This would also apply for the other casals of Hubelet, Dersoet, Derlauha and Kafra, offering the image of an almost deserted plateau in the first half of the twelfth century. As will be seen below (cf. Dorso same document) this hypothesis cannot be invalidated or confirmed on the basis of archeological surveys. If this should be the case, Cocquet, and perhaps the neighboring villages of the plateau, could have been reoccupied after a period of abandonment, following the Frankish conquest. This reinvestment of the area would then have taken place after 1132. Ronnie Ellenblum has suggested that the persistence of local place names during the Frankish period and the subsequent assignment of new Latin names are indicative of the establishment of the Frankish population9. This hypothesis would apply well to the case of Cocquet/Belvear, less so with respect to the neighboring casas, whose names derive from the Arabic (Yubla, Dayr Sawād (?), Dayr Lawha (?), Kafra).

Casal Cocquet appears for the third and last time in a 1168 royal confirmation of the acquisition of several casals on the plateau by the Hospital. The deed, dated April 1168, doesn’t mention the date of acquisition of Cocquet but it indicates that the village was bought from a certain Ivo Velos for 1400 bezants10. Two details are also important: Cocquet is the first of the seven casals to be mentioned, and it appears as castrum de Coquet, carrying the new name of Belvear. The most common practice in this type of confirmation is to refer to the transactions in their chronological order, probably following the classifications of charters in the archives. We have the deed of donation by Walter of Galilee of the casals of Derlauha et Dersoet. It is dated 1165. However, in the deed of 1168, they both appear after Cocquet. From the position of Cocquet in the text and from its new name, we should probably see the preeminence of the site within its new context, the hospital domain of Belvoir. In my mind, the name castrum can only be understood with the adoption of the new name Belvoir, which means that, in 1168, the site was already fortified or being fortified. The act of 1168 ratifies the disappearance of the toponym Cocquet. The name Kawkab, however, will still be used in Arabic, the castle being known as Kawkab al-Hawā, “the star of the winds”, and, in modern Hebrew, as Kokhav haYarden (Star of the Jordan).

The hypothesis that Cocquet was a Frankish foundation has, to our knowledge, never been stated as such. However, this was implied when Professor Benjamin Z. Kedar gave us an aerial photograph of the site from 1954, six years after the attack and destruction of the modern village of Kawkab al-Hawā. On this good-quality print, one could clearly see the two developments that made up the village. The first one, which kept the general shape of the castle whose ruins it was built on, was a dense tangle of small alleys leading to stone and earthen houses, sometimes organized around central courtyards. The second development was more atypical: it consisted of two rows of square buildings separated by a lane. This layout, uncommon among modern Palestinian villages usually organized in concentric circles, led our team to study the village. During the Second World War, Italian Franciscan priests were assigned to residence in the properties of the Order as enemy citizens residing in the Palestinian Mandate. In al-Qubeibeh, the Frankish Emmaus, excavations led by Father Bagatti uncovered well-preserved vestiges of a Frankish one-street town11. Adding to the data of the excavation, a rich documentation allowed for the interpretation of this village as a Frankish foundation whose vocation was to receive European settlers12. The site, which depended on the canons of the Holy Sepulchre, is not the only Medieval village of its kind. Several other villages were subsequently uncovered and studied, all of them around Jerusalem and linked to the Priory of the Holy Sepulchre. A one-street town south of Belvoir, albeit modern, could be the fossilization of an older dwelling. This would suggest that the hospital castle was established north of a village of Frankish settlers.

In 2013, the soundings of our first dig season were opened in the area of the one-street town. This was not an easy task: the ruins of the village, which could be seen on the photograph from 1954, had completely disappeared, probably since the early 1960s, judging by the aerial photographs of the time. The establishment of a grid in the field, based on the rare eucalyptus trees still in the area, made it possible to open two soundings at the location of two separate buildings in the one-street town. These two surveys revealed two distinct modern buildings: only the foundations of the square building were preserved. The other, smaller building was a residence. The dating material we gathered dated back to the late Ottoman period. Our hopes were thwarted. The following year, in 2014, another sounding was implemented in the area, more to the south, on buildings partially preserved in elevation. Here too, the natural soil under the house only revealed Ottoman material. A few months later, while doing further research on the modern occupation of villages on the plateau, we learned that this extension of the village of Kawkab al-Hawā dated from 1870. It was a foundation, maybe with the aim of colonizing since that part of the village was built on State land by order of the Sultan Abdül Hamid II (1876-1909), in pursuit of his policy of sedentism of the Bedouins of the Jordan Valley13. The odds that the first one-street town of Galilee had been on the site of Cocquet were getting away. In 2014, still with no concluding results, the excavations were extended to the castle itself. Four soundings were undertaken, in two of the towers, the western gallery and the central courtyard of the castle. We’ll only develop here the results from this last sector, although some developments that predated the fortification were unearthed in the gallery. Unfortunately, in the absence of archeological material, they can only be dated by relative chronology.

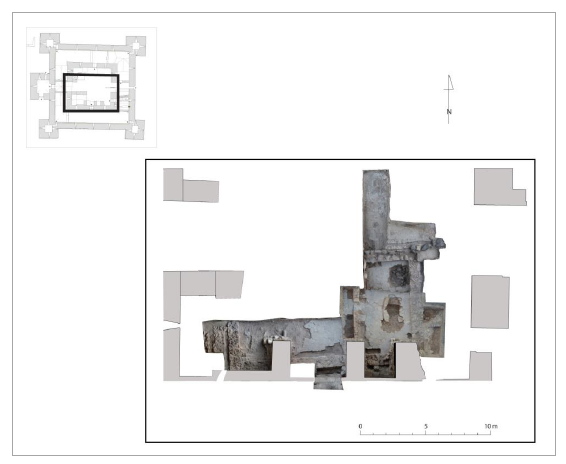

In 2014, one of the soundings was in the inner courtyard (Fig. 1). As early as the first campaign, a set of masonry structures predating the hospital castle were unearthed. For technical reasons (short excavation seasons, need to backfill between seasons, traffic constraints), the excavation was undertaken in successive segments in 2014, 2015, 2016 and could never be fully completed.

Immediately underneath the contemporary traffic level, which results from the post-clearing development of the 1960s, as well as a rather intense tourist traffic, is a rather hard and thick ground of white lime mortar. A pipe, visible from the surface, runs across it from west to east. The cover, which has only been preserved outside of the hole, is covered with basalt slabs placed on a conduit made of two low walls of uneven rubble stones bound with mortar. Several pits pierce the ground: northwest and to the north of the pipe, of irregular shape, possibly the result of recent work, and a trench that seems to be the negative of another pipe. Under the hard floor, we found an invert made of small blocks of basalt bound with earth, along the pipe, perhaps it had a draining function. We found two levels of pinkish brown floor alternated with layers of ashes. To the south of the pipe, the northern wall of a building, against which the pipe rested, was uncovered.

Under the staircase arch, several structures were found: At ground level of the courtyard, a paving of big basalt stones and, in front of the arcade, the remains of an oven installed on the level of a lower wall. The oven opens to the courtyard, facing north. Its mouth is surrounded by two limestone rocks. Its bottom is made of irregular flat stones and rubified earth. It was filled with a compact layer of ashes that spilled northward through the mouth of the oven to spread a little in front. We can’t ascertain whether the oven, which is very rustic, was covered by a stone or an earthen dome, or if it was open. The oven was situated in the ruins of the southern wall of the building and its associated material is modern.

The built structures that have been exposed in the area make up a building kept on high foundations (Fig. 2). We can apprehend its general plan, except for the north-west corner, which remains unknown. It forms a rectangle of 15 m par 8.50 m, including 0.65 m large perimeter walls made of irregular basalt blocks bound with clay and chained in the corners. A 0.45 m wide partition wall leans on the north and south wall and separate the interior into two unequal surface units: a main room to the west (53.8 m2) and another to the west (26 m2 or half the size). The wall is pierced in its center by a 0.65 m large door. The floor is covered with a neat paving of informal stones that rest on the internal facings of the walls. These are fragments of informal flat stones, mostly basalt, arranged and interlocked with mortar joints to form a smooth and horizontal plane. This arrangement lies on a fill of earth and small stones intended to level the surface between the underlying rock flushing. The access to the building is unknown; no door has been found. It was probably in the northern wall of the west room. In both rooms, interior facings of the building are covered with a plaster of fine lime mortar, white-yellow in color, one centimeter thick on average, very covering and leaving only a few stones seen with, in some places, lines dawn with an iron. The walls were plastered only after the floor had been laid.

Along and at the base of the walls 0.50 m wide masonry benches are arranged, built with earth-bound ashlars and plastered like the walls (Fig. 3). Except for one small fragment, these benches are only known from the regular negative that their removal left in the paved ground that rested against them. Their arrangement is not systematic: they are found in the west room, along the southern and eastern walls, and in the east room, along the western wall and part of the northern wall. In the east room, a masonry structure is placed in a central position facing the door. It is composed of two large limestone blocks cut in a round shape on their outer face and left rough on the other, arranged in a circular arc. They rest at a level below the paving, on the natural ground that was probably slightly excavated to accommodate them, and are wedged in place by stone fragments. This structure, probably partly torn away, may have belonged to an artisanal or decorative element.

The building as a whole presents very degraded remains: in addition to the general leveling of the walls and the removal of the benches, the floor is largely torn up in the west room, and in the other it is pierced by a pit of nearly 2 m in diameter in the northeast corner, as well as in the vicinity of the central structure.

The building, on its level, is filled with a layer of destruction coming from the walls and resting on the ground and in the holes that affect it. Above, sealing the level of the walls, a layer of reddish-brown earth and stones, which must also have come from the walls, seems to have been spread out to drown the ruins and to constitute a flat and regular level for the construction of the castle. This primitive building is indeed established on the natural summit of the site which supports the castle before the erection of the latter. The walls of the building rested, where we could see it, either on the basalt rock in place, or in foundation trenches dug in a compact yellow-green marl, also in place.

Fig. 3 Relationship with the staircase pillar. The layer of destruction of the primitive building being present only on the low height preserved of the walls, leads to think that the ruins were largely evacuated to make place for the construction of the castle.

The contacts between the structures show that the foundations of staircase piers of the castle cut into or rest directly on the wall level of this older building (Fig. 4). This is the case in the southeast corner, at the junction of the south wall and the wall of the south room, and in the center of the south wall of the west room. In places, the reddish layer has been cut into to allow the foundation of the pillars to sit on these older walls. There is no direct relationship between the primitive building and the castle itself, which was built around the middle of the twelfth century, the north façade wall on the courtyard being located one meter from the underlaying south wall. Only the relationship with the staircase is attested, but this one, which appears to be a posterior arrangement on the façade, is however, in all likelihood, part of the initial project of the hospital castle. The construction of this staircase was accompanied by the raising of the circulation level of the courtyard, at least inside the arcade, materialized by large basalt slabs resting on a small stone base, all of which covered the overhanging foundation blocks of the two pillars. It is therefore clear that the destruction and leveling of the original building took place before the castle itself was built.

The information that can be drawn from these data concerns first of all the exterior aspect since nowhere do the perimeter walls seem to be in contact with other structures; if, to the west, a parallel wall of the same nature and width has been uncovered, it is separated from the western wall of the building by a space of 0.30 m, which indicates that it is probably another building, which has not been recognized. We would therefore be in the presence of a building of about 128 m2 overall with two communicating rooms. This building probably had only one floor, as the thin earth-bound walls do not seem to have been able to support a second floor. The method of roofing is not known: one can exclude the tile, totally absent, and wonder about the possibility of a roof terrace when one notes the need for beams of 8 m long. Concerning the interior, one must insist on the care taken with the covering: floor paving and wall plastering, the presence of numerous benches in both rooms, suggest a reception function. However, we can’t be more specific about it. Finally, although it could not be identified, the central structure of the room is undoubtedly an important element for the function and decoration of the whole (Fig. 5).

In a 1992 article, Ronnie Ellenblum attempted to highlight technical criteria that would allow constructions to be attributed to the Frankish period14. I From studying 103 sites, 63 of which were suitably dated to the twelfth century, he retained four main criteria: diagonal cutting, which appeared in twelfth-century Palestine, the extensive use of barrel vaulting, materialized after its destruction by the existence of putlog holes, lapidary marks and the recurrent use of peripheral chasing. Unfortunately, the state of preservation of the remains at Belvoir does not allow us to retain these criteria, although a bloc of stone found at the edge of the south-eastern pit of the building clearly shows a diagonal cut. Neither the plan of the building, nor the specific fitting such as the benches and the plaster, allow us to be categorical. These are found at several Frankish rural sites, such as at Har Ḥoẓevim, north of Jerusalem. The latter site, excavated in1994, has a plan and internal layout very similar to the building uncovered in the courtyard of Belvoir15. The complex consists of an uneven enclosure forming two courtyards to the north and east, enclosing a main building against which two annexed spaces are adjoined. The central building has a rectangular plan and in internal division, with two annex rooms. The site was interpreted by archeologists as being a farm, based on the existence of artisanal and agricultural structures.

As a provisional conclusion, one is of course tempted to relate these remains of a primitive building to the existence of the rural settlement sold by the Frankish Yves Velos in 1168 to the Hospitallers. According to the documentation, the first settlement could have been built between 1132 and 1165 (casal Coquet). It is indeed a rustic construction (earth-bound masonry), but its neatness (paving and plastering) seems to differentiate it from a simple peasant house. We can assume that it is a domain center near a rural village.