Underlying the texts we medieval historians read is an ocean of ephemera to which we have no direct access. This was the human world which produced our written texts, comprised of words spoken, feelings felt, information exchanged, and personal connections, in short, a mass of movement and change that flows beneath the static and unchanging words we find on the page. What chroniclers wrote was always intended to take fluid and abstract material and mold it into a concrete and durable shape. Medieval historians frequently made this claim explicitly, when they asserted that they wrote to prevent their subject matter from falling into oblivion. They were generally less explicit about the particular forms their histories took, leaving modern scholars guessing at how they decided on how to structure their narratives.

Occasionally, however, we can catch a glimpse at the world behind the text. In this paper, I present one such case, concerning two roughly contemporary histories. Although neither work references the other and they were written at monasteries without any formal record of contact between them, on different sides of the English Channel, at least one element of both narratives is so strikingly similar, produced under such similar circumstances, and yet so different from other works of this genre, that it is difficult not to conclude that one did not influence the other.

The two works in question are William’s Chronicle of Andres and Thomas of Marlborough’s Chronicle of Evesham. In my analysis, I will demonstrate that is likely that Thomas and William met and that Thomas influenced William to write a chronicle of his monastery that included a legal narrative similar to the one contained in the Evesham chronicle. The argument is hypothetical, of necessity. But even if it is solely a product of my imaginative reconstruction, it may serve as a reminder of how important it is to keep in mind the incontrovertible fact that our authors, like all other authors, were people: they traveled; they met other people and formed relationships with them; they had serious discussions with them; and that many of these aspects of their lives, which shaped the histories they wrote, sometimes profoundly, have left little or no trace in the records.

The witnesses

Thomas of Marlborough’s Chronicle of Evesham survives in a single manuscript that does not seem to have been read outside the monastery. Thomas began putting together his chronicle around 1214. It contains an adaptation of materials created earlier, to which he added the contemporary portion of his history. His most recent editors and only translators, Sayers and Watkiss, however, think he wrote up his notes about the monastery’s legal case, in which he played a starring role, between 1206 and 1208; he may have revised his text as late as 1230, and it is possible that he wrote the account of his deeds as abbot, with the obvious proviso that the account of his death in 1236 has to have been written by someone else1.

The other author under discussion here, William of Andres, wrote at Andres, a small monastery in the Pas-de-Calais about halfway between Calais and Saint-Omer2. William compiled his chronicle from other texts he had read and were available to him, primarily excerpts of the Historia succincta of Andreas of Marchiennes and the Anchin continuation of the Chronicle of Sigebert of Gembloux, possibly also by Andreas3. William interpolated the history and charters of his monastery into this framework and, when his source material ran out, wrote from his own knowledge.

When William began writing is more difficult to ascertain. He was already abbot of Andres when he was writing, which puts the date at 1211 at the earliest4. But the date of composition is probably later than this. When speaking about Abbot Iterius of Andres, who was translated in 1207 from Andres to Ham-en-Artois, William notes that Iterius ruled Ham for thirteen more years but never did much for his new house5. Thus, the composition of this part of the chronicle, at least, can be no earlier than 1220. Finally, in relation to a discussion of the liturgical practice of the monastery, he notes the sixty-four years during which the liturgical practices instituted by Abbot Peter II had been maintained. Since Peter became abbot in 1161, this puts the date of composition of this part of the narrative around 12236. Whenever he began, William continued his chronicle to 1234, when he died7.

Although both chroniclers were well-educated, Thomas was formidably so. He had studied in Paris under Stephen Langton and then at Oxford under legal scholars, before entering Evesham as a mature adult, perhaps in his early thirties8. William, in contrast, seems to have received all of his education at his monastery, which he entered sometime in his teens9. He valued literacy-he comments on those he considered to be less literate than was appropriate for their stations, reflecting the varying levels of literacy common in the monastic life-and he mentions that while in Paris, he attended lectures in theology when he could-but his knowledge of the law was practical, learned on the job as the proctor of his monastery and through his conversations with legal professionals10.

The scope of the two works was different as well. Thomas’s task was to write the history of Evesham, explaining the sources of its authority and privileges, particularly the most precious privilege, exemption from the authority of the bishop of Worcester. He was building on at least two spurts of writing at Evesham before him11. However, there was still much to explain; the monks believed their monastery to have been founded in the eighth century, but the records were patchy; for a time the monastery was in the hands of secular clergy. After its reconstitution Evesham was large, with an estimated forty to fifty monks. It had enjoyed royal patronage and was certainly wealthy, as the accounts Thomas included make clear12.

In contrast, Andres was of relatively recent vintage, forcing William to draw on the historical works of Andreas of Marchiennes as base texts. In using materials from Marchiennes, William was, in fact, taking a slightly audacious step, because Andres claimed that their St. Rotrude was the same as St. Rictrude, whose body Marchiennes vigorously asserted that it still possessed13. Andres was never very large, with a community of perhaps only twelve to twenty monks for most of the time. The highest-ranked patrons were the counts of Guines and the family of the lords of Fiennes. To the degree that the monastery did well, it was through careful management of its resources, a nice side business in money-lending, and donations generated by its almshouse, which functioned as an inn14.

Given their different contexts, it is no surprise that there is no overlap in content between these two chronicles. Although the two works were created with the same intention-protecting the property and prerogatives of their respective monasteries-they took different approaches to this issue. Nonetheless, the texts were prompted by the same situation: both monasteries experienced crises of jurisdiction within the same decade both of which ended up at the papal court of Innocent III. This was hardly unusual. As Alain Boureau has eloquently argued, law came to the monks in this period, and difficulties which in an earlier age might be resolved by retribution by a saint might now lead to legal wrangling15. Each author was chosen as the proctor of his respective monastery for the case and spent long periods in Rome while the case was being heard. Each history contains lengthy and detailed accounts of this process, including transcripts of papal privileges and other supporting documents. The most striking feature of these accounts, however, is that both are told in the first-person singular; in each, the narrator is also the hero, successfully waging war on behalf of his monastery. Once the drama ended, however, both texts continue in the third person, the only known chronicles to use this strategy.

The cases

Evesham’s case arose in 1202, when the bishop of Worcester informed the monastery that he was planning to make a visitation. His reason was the evident deficiency of the abbot, Roger Norreis, who had been imposed on the monastery after the death of Abbot Adam in 1189. The monks had several times complained to the archbishop of Canterbury, Hubert Walter, about Norreis's laxity and alienation of monastery property. In doing so, they had bypassed the bishop of Worcester, since Evesham claimed an exemption from episcopal authority, even though a number of the abbots had been blessed by and made profession to previous bishops of Worcester. Thomas argued to his brethren that permitting the bishop to make a visitation would mean they were subject to diocesan authority. While not all of the monks agreed, the party in favor of asserting Evesham’s exemption from episcopal authority won the day.

The next events that Thomas narrates are immensely complicated. The abbot acted sometimes as a mortal enemy and sometimes as an ally to his own monks according to circumstance. Eventually, the case went to Rome where it was resolved, although not fully, in 1206. Thomas acted throughout on behalf of the convent16. This was not the end of the legal wranging. When a papal legate came to hear the case against Roger Norreis in 1213, which led to Norreis’s deposition, Thomas once again led the charge.

Andres’s case was slightly later and rather simpler. Andres had always taken its abbots from among the monks of its motherhouse, Charroux in Poitou, but according to William’s account, this was always a source of discord within the monastery. After an abortive attempt to get a local man appointed, the grandson of the Count of Guines, the monks seem to have settled under yet another southern abbot, Peter II. William greatly admired Peter, but he put a prophecy in Peter’s mouth on his deathbed, that the next Poitevin abbot would be the last. Peter was indeed followed by another Poitevin, Iterius. When Abbot Iterius was translated from Andres to Ham-en-Artois in 1207, he immediately sued the monastery for plotting to choose an abbot from their own numbers. One suspects he heard muttering and acted in the interests of Charroux. William was chosen to travel to Charroux to see if the matter could be peacefully settled, but his plea fell on deaf ears. He then made his way to the papal court, the first of several trips. After several hearings at the curia, Innocent III assigned the case to judges delegate who heard it in Paris. The judges were divided in their legal opinions, which resulted in the case being sent back to Rome, where it was finally settled by compromise in 1211.

In both cases, the authors of the chronicles had to continue to deal with people who had been opponents to their efforts. Roger Norreis, sometime ally and frequent enemy of Thomas, was not deposed as abbot of Evesham until 1213, and the matter of the authority of the bishops of Worcester was not settled. Thomas was by then a power in his own right at Evesham, first as dean of the Vale of Evesham and sacrist, and then as prior, but he only became abbot later on. In contrast, William was elected abbot of Andres in 1211. However, Andres was not exempt from the oversight of the bishop of Thérouanne, and that see was now held by Adam, one of the men who had ruled against Andres’s case as judge delegate.

First-person-singular narrative

Given that Evesham’s case was not fully settled, and William’s opponent now was in a position to punish Andres, both men must have wanted to document what had been done, so as to protect the gains of their respective monasteries. The decision to document them using a first-person narrative, however, needs some further exploration. First-person singular narration, or self-writing, was not unusual in twelfth-century Latin texts. Many of these texts might be classified as autobiographies, although the application of that term to medieval texts is far from uncontested17. Gur Zak lists a number of modes of self-writing inherited from the classical world: self-examination and self-portrait (tending toward exculpation). This presupposes a work whose entire focus (or most of the focus anyway) is on the author of the piece, but neither William’s nor Thomas’s narrative fits into that mode, as each is set, jewel-like, in the middle of more traditional narrative history. Furthermore, many self-referring works of the confessional mode did not really have readers until the print era18. And yet both Thomas’s work and William’s work presuppose local readers. Thomas addresses them explicitly (in the first person singular); William’s relation to readers is implicit for the most part, aside from the letter that introduces the original part of his text19.

Finally, the intention of these two texts is not like other contemporary Latin self-writing. Misch has related the rise of autobiographical narratives to changes in ecclesiastical structures and religious ideas20. Yet neither Thomas nor William could be said to be justifying themselves or examining their actions critically, as their actions clearly benefitted their respective monasteries and therefore needed no justification. Instead, they relate what they said and heard and did, often with considerable pride. This is similar to trends emerging in French vernacular narratives around this time, particularly when the authors were also historical actors, particularly knights21.

Furthermore, in both cases, the first-person passages concern not just any deeds, but legal combat. The details mattered, particularly in the case of Evesham, whose case was not fully settled. Each man could have chosen to write his narrative in the third person, but the first-person narrative has a rhetorical vividness that calls attention to the demonstrative purpose of the text. That this move also calls positive attention to the author is a given, but is clearly not the main purpose, as neither author continues with it past the conclusion of his monastery’s case.

Since there are no other cases where this kind of detailed treatment of legal procedures occurs in a first-person singular narrative22, it is hard to imagine that two men who happened to act as proctors for their monasteries in cases before the court of Innocent III within a decade of each other and whose cases happened to end up in the third of the five ancient legal collections of canon law made under Innocent took an identical approach to their narratives by chance23.

As the two texts share no material and did not circulate, and since neither author mentions the other, if one author had influenced the other, it was not through a text. Because Thomas began writing first, the idea of the first-person narrative was probably his. I have already mentioned the extensive legal training that led to him being chosen to represent the monastery24. His narrative includes a lot of instructions and advice for his successors about how they should act in the future and what procedures they should follow if challenged25. As a legally trained individual, he would have been aware of procedural manuals, which could be based on real cases, so that in essence his narrative would be a procedural manual for his monastery26.

If William had legal training before he undertook his monastery’s case, he does not say so27. He may have been the monastery’s notary, as a notary named William witnessed an agreement between Andres and Cluny in 1197. If so, he would have had some practical legal training, but four different Williams are mentioned in that document28. Thus we have no idea why William was chosen by his monastery as their proctor, but it need not have been extensive legal experience29. Eventually, he learned enough that he himself served several times as a judge delegate30. But his comments in the chronicle do not demonstrate the same depth of legal knowledge that Thomas exhibits. He does report an argument he made before the pope based on the ius commune, but shortly before, he claims that he is just a poor and unlearned cloister monk, so it is difficult to ascertain his real level of knowledge31.

Thomas, in contrast, was much more aware of the full extent of the law and how to maneuver in the papal court (William says he had to be instructed on how to go about this when he first arrived)32. Although both monasteries were rei (defendents) in the litigation, only Thomas mentions that this was an advantageous position to be in33. Thomas freely refers to the procedures of the papal court, such as interlocutory judgments; to a lengthy argument with his opponent over the demands of ius commune (claimed by his opponent) and the power of prescription (claimed by Thomas on behalf of the monks); to instructions for the monks about how to act so as to have the ius commune on their sides and how to handle their case should the matter come up again; to lessons he had learned from the glossator Azo; and to his own legal delaying tactics34. Clearly, Thomas had the legal knowledge to turn his narrative into a sort of procedural manual, so he was likely the originator of this particular narrative form.

But how could William have known what Thomas had done, given that the two men were at Innocent’s court at different times and that there is no reason to believe that he had ever read the Chronicle of Evesham, which does not seem to have circulated beyond the abbey’s walls35? A possible answer is that the two men had met and that in the course of an unrecorded conversation, something Thomas said persuaded William to write his own chronicle or to incorporate Thomas’s mode of proceeding into a chronicle that William was already writing.

We know that medieval people were having conversations. Caesarius of Heisterbach’s Dialog on Miracles famously relies on people telling each other stories36. Similarly, we know of Walter Map’s reputation as a great and witty talker, but if John of Wells at Ramsay had not had a taste for his work, we would likely not have it and Map would be known only by the Dissuasio Valerii and the documents in which he appears37. Very occasionally a written text will convey a sense of the kinds of conversations people had, such as the conversations recorded by Jocelin of Brakelond in his Chronicle of Bury St Edmunds38. Thomas of Marlborough similarly reports that he had a conversation with Stephen Langton and Richard Poore that lasted far into the night, although he does not mention any specifics39. Many such conversations would have gone unrecorded and if recorded, these cannot be taken as true reports anyway40. So if a conversation took place between Thomas and William, we would not necessarily have had a record of it. Nevertheless, the two men linguistically speaking would have been able to converse. Notwithstanding the vigor of the vernacular and the inability of some monks to function fluently in Latin, these men made arguments at the papal court and wrote lengthy histories in Latin. Their learning was important to their identities41. The vernacular at Andres seems to have been Flemish, but William certainly knew French, the language of the noble elites in the area; Thomas had studied in Paris, so he undoubtedly spoke French as well. Therefore, if William and Thomas had met, they would not only be able to communicate, but they might even have had a choice of languages in which to do it42.

Networks and prestige

This does not explain, however, why William should have taken advice from Thomas about how to compose his history. Here, a little theory may be helpful, a theory already implied by what has been said earlier. There is a tendency to think about texts moving from one place to another, but the reality behind those movements is that they are carried by people. Someone, perhaps Robert of Gloucester, carried a copy of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Gesta regum Britanniae to Bec. Henry of Huntingdon encountered it there and wrote an abbreviation43. The prestige of Bec enhanced the prestige of the work, while Henry further disseminated it by including an abbreviated version in his own chronicle44. This book, therefore, had a reputation and status created by what the sociologist Randall Collins has called interaction ritual chains, where one local set of circumstances (the monastery of Andres, for example) meets another local set (Canterbury) through individuals who act as brokers, providing contact between the two45.

In the absence of connections among people that might spread a work or scholarly reputation (also passed, if more diffusely, among people), even a work with a lot of merit might languish. The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis, a history that has generated great interest in our own time for the quantity and quality of the material it offers, had little impact in its own day. There are all sorts of reasons for this, not least that Orderic’s institution, while it had connections, was not as well connected as, for instance, Bec. In Collins’s terms, Orderic’s work had emotional energy-the part that makes modern scholars recognize its value-but not cultural capital46. Orderic’s other work, his revision of the Gesta Normannorum ducum of William of Jumièges, circulated more widely, undoubtedly benefitting from William’s reputation and from the sheen imparted by ducal patronage. Contemporaries probably did not know that Orderic had revised it47. William of Jumièges’s work, on the other hand, had a lot of cultural capital, shown by the fact that it not only spawned a number of copies but also gave birth to revisions by Orderic and by Robert of Torigni. This is in keeping with Collins’s argument that the most powerful work is work that allows people to make their own statements48. But connections made through books are relatively weak. Stronger connections work through people49.

It is also useful to add the notion of attention-space to this theory of connectivity. In a world clamoring with people trying to get attention and influence, only some will get it. Part of determining who gets that attention will be what Collins calls the ‘lineage of the intellectual’, while part of it is also related to one’s ability to connect with high-status ideas50. Individuals will bring their utterances into conformity with members of the network or lineage they wish to be attached to51.

This raises the question of why Thomas would have gotten the attention of William, inspiring William to imitate his work or take his advice. Thomas was locally important, but his reputation probably did not extend across the channel. Status, however, was not entirely a personal matter; it was also derived from one’s position in relation to various networks. Thomas was attached to a highly significant network, one to which William was also connected.

Thomas of Marlborough’s network

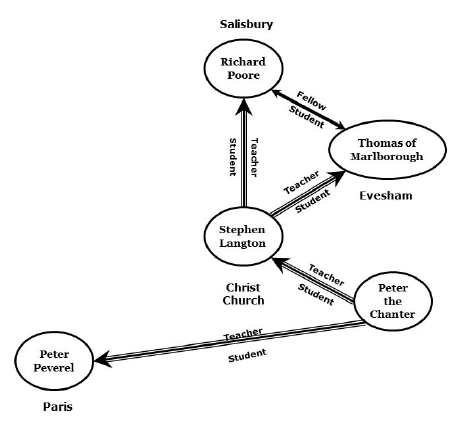

Thomas had studied in Paris with Stephen Langton, where he was a fellow student of Richard Poore, the archdeacon of Salisbury and later the bishop in turn of Chichester, Salisbury and Durham; as mentioned above, Thomas describes the three of them coming together in London in 1213 and talking until midnight about the state of Evesham. That they did so is an indication of the strength of the ties among them, strong in sociological terms, because they were of long duration and arose from structures that shaped the relationship, namely teacher-student and fellow-student relationships. The term “strong ties” as I’m using it here comes from the work of Mark Granovetter, and such ties contrast with “weak ties.”

The set of people made up of any individual and his or her acquaintances comprises a low-density network (one in which many of the possible relational lines are absent) whereas the set consisting of the same individual and his or her close friends will be densely knit (many of the possible lines are present)52.

Not only were these three men bound by their shared experiences in the schools: Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury was responsible to the pope for Evesham, which had effectively won its independence from the bishop of Worcester. These ties would have strengthened over time as Thomas became prior and then abbot of Evesham, while Richard too rose in the ranks, and connections would have been enhanced by a common circle of friends and acquaintances53. Langton himself profited in reputation by being associated with another intellectual circle, that of Peter the Chanter at Paris, which probably enhanced his reputation as a theologian54. Thomas also had other connections through his legal training to men such as John of Tynemouth, Simon of Sywell, and Master Honorius, but these other connections do not seem to have played a role in this story55. We might picture this relationship, then, thus (with an additional figure we will need later on).

The network of William of Andres

The first figure from this group whom William met was Langton. When William arrived in Viterbo in 1207 he found Langton there56. While it is possible that Langton had been in William’s proximity before, as Andres was a regular stopping place on the route from England to various points on the continent-Innocent III had stopped there himself as a student at Paris57-William does not seem to have actually met him prior to this point. Why should he, a monk who does not seem ever to have been the almoner, have met guests who stayed in the hostelry?

However, there were institutional ties between Christ Church Canterbury and Andres of long-standing. After a fire destroyed much of Andres around 1130, the monks of Christ Church sent the Flemish monks their used clothing and bedding, which they continued to do for years afterward. This too was the result of a chain of ties: Count Manasses of Guines married Emma of Tancarville, heiress to Folkestone (near Dover), and had in his service a retainer named Ralph of Dover, probably as a result of this English connection. It was Ralph who had negotiated the English charity58. So when William arrived in Viterbo without much money, he was a natural recipient of further largesse. William’s connection to Langton can be characterised as a ‘weak tie’, but he used it to his advantage.

Through the monks of Christ Church, who were there on their own business, William met Stephen Langton at an opportune moment, just before Langton’s election and consecration.

We were present at his consecration after a few days and on that day, urged and invited, we were his table mate. We also found the grace entreated from him just as we had hoped at his side. Also from his aforementioned monks, we were received for a time into their lodging in the spacious house that they rented, because of the poverty of our dwelling; we were dutifully refreshed by their words and advice; we were informed more fully of the state of the court, how we might approach the lord pope and how we might explain our business; and we were well taught how we might visit cardinals59.

This may reverse the nature of the ties-the ties between Christ Church and Andres probably brought William into the orbit of Stephen Langton, not the other way around. We also know that Langton urged Innocent III to issue a privilege for Andres (although the privilege was later rescinded)60. Langton’s ties with Innocent would have gone back to their Paris days. Although Innocent III is not represented in this network diagram, we may think of him as being in the background of all of these transactions.

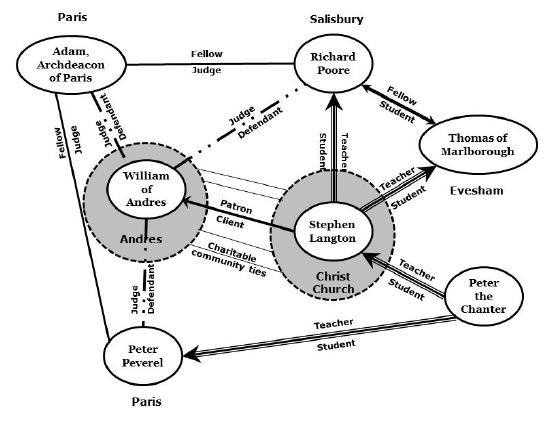

William returned to Rome a second time following an attempt by his adversaries to summon him to nearly simultaneous hearings in venues days apart from each other61. By the time he arrived back in Rome, Stephen Langton was probably at Pontigny (where Thomas Becket had once taken refuge before him), but when Innocent sent the case out to judges delegate, one of the three men appointed was Richard Poore, who was teaching in Paris while Langton was in exile. We have already encountered Poore as a former student of Langton’s and a friend of Thomas of Marlborough. The second judge was Peter Peverel or Polverel (there are different spellings in different documents), who came, like Langton, from the circle of Peter the Chanter62. The third judge, who like Peter Peverel was a canon at Paris, was Archdeacon Adam. His connection to the network is not clear, but he later became bishop of Thérouanne, and thus ordinary of Andres63.

Of the three, Poore was the only one to favor Andres’s case, and quite forcefully so.

However, when I who writes these things had been sent with the prior on behalf of the corporation and for two whole days had made a lengthy argument before these aforementioned judges, since it was clear to us as much by certain outward gestures and through some of the judicial assistants that of the three judges, only the dean of Salisbury faithfully stood by us, and that the other side awaited a definitive sentence in their favor from the two remaining ones, in the end, our side asked that the case be sent back, sufficiently explained, to the lord pope to be concluded according to the form of the commission. This was completely and openly refused by the two, because in the commission was contained not a matter of one side but of both sides. Then while we were asking the referral to be made and demanding that nothing should be done otherwise through an appeal and while his fellow judges were ruling that we were bound to elect someone from the chapter of the church of Charroux, the aforementioned dean of Salisbury got up from the consistory, along with his assistants who were discrete men and learned in both laws, not having approved of their judgment, and decreed in the presence of many that the case ought to be sent back to the lord pope. He said that he would by no means give assent to the sentence of his fellow justices and to the degree that he was able, he faithfully sent testimonies, allegations and other reasons pertaining to the suitability of the case to the lord pope enclosed with a seal, and also diligently explained through letters patent his mind’s impression concerning the things he had heard and seen64.

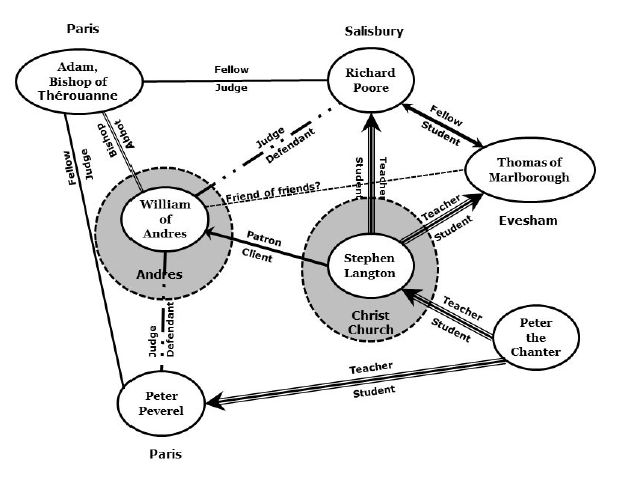

It is hard not to see the strength of Langton’s connection with Poore here. If we were to reconfigure the relationship diagram, it would now have to look like this:

Although the ties that bound William to Stephen Langton were weak, they operated on two levels, personal and institutional. William’s relationship with each of his three judges was, on the surface, the same, but Langton was lurking in the background of his relationship with Richard Poore. Just as Langton acted as William’s patron with Innocent III, he may have also done with Richard Poore. All of this help seems to have tipped the balance in favor of Andres, which won what it most wanted: the right to elect its abbots from among its own monks. William came home triumphant and was elected abbot and the monks of Charroux acquiesced gracefully. William’s success was thus a classic demonstration of Granovetter’s principle of the “strength of weak ties.” Through the cultivation of people he initially did not know very well, William himself managed to rise in the world.

Bringing Thomas and William together

Now all of this would explain why, if Langton had offered William advice, William would have listened. But it does not explain why William would have listened to Thomas, although it does establish a vector for a potential meeting between the two men. To explain that, we should think further about Langton on his own terms, not just the role he played in William’s case. To William, Langton was a literary figure as well as a powerful man. His obituary of Langton stresses this:

Lord Stephen of felicitous memory, the archbishop of Canterbury, a man outstandingly literate in his time, adorned by no means moderately with morals and doctrine, given to alms and everywhere known, died in a blessed state, and when he had been carried to his church, he received burial in it65.

Langton’s literary reputation not only validated his own person: It had the power to validate his students. He occupied more intellectual attention space in his day, to use Collins’s phrase, than we tend to currently credit him with; Magna Carta and Langton’s political role loom so large for us that until recently appreciation for his erudition has suffered66. It is not necessary to assume that William knew any of Langton’s work personally, although there are many manuscripts of his various works and it is quite likely that William had heard Langton preach in Rome if nowhere else 67. It would suffice, however, for William to travel in circles in which Langton’s work was known and talked about. Langton’s reputation, once established in William’s eyes, in turn would establish a reputation for Thomas. And of course Langton was a very important man, by virtue of being the primate of England.

Because Langton was the most important node of the network, and because Thomas was closer to him, he was upstream of William in the network and therefore worthy of being listened to. We might imagine Langton introducing the two men to each other and referring to their shared experiences in the court of Innocent III and suggesting they compare their notes. Perhaps they shared horror stories about Abbot Iterius and Abbot Roger Norreis, both of whom ended up deposed. We might imagine Thomas, whose knowledge of law would have been important in this story once the two men became acquainted, noting that William’s former judge was now his ordinary. While Andres had never claimed exemption from the authority of the bishop of Thérouanne, perhaps the bishop might bear a bit of a grudge? Even if he did not, it would be hard to defend the monastery’s property after a four-year vacancy and the aftermath of the upheaval leading up to the battle of Bouvines.

Armies had ravaged the county of Guines and William only managed to save Ardres (seven kilometers from Andres) from being burned by pooling his funds with the abbot of Capella and a local priest and paying a stiff ransom68. Adam had already made a mistake about the monastery’s property in 1216 and such mistakes might be easy to make if records were not good69. One can imagine Thomas pointing these things out and William thinking about them and putting them into textual action, but giving them his own spin and stress, drawing upon materials Thomas did not use, while keeping enough of Thomas’s mode of proceeding that the connection could remain evident to us.

A crossing of paths

Stephen Langton was the “structural hole”, the link or node, that connected William of Andres to Richard Poore and Thomas of Marlborough70. In addition Richard Poore was also a structural hole between William and Thomas. Either Poore or Langton could have introduced William to Thomas, were they to have found themselves in the same place at the same time. Therefore, we have to ask where and when it would have been possible for these two men to have met, with or without Langton or Poore acting as a broker.

According to Thomas’s narrative, he set off for Rome in late September of 120471. It is certainly possible that he went by way of Andres, since one route from London to Paris went by the monastery72. But if Thomas stayed at Andres, there is no particular reason he should have met William then, because as far as we can tell, in 1204 William was just an ordinary monk at the monastery. Furthermore, the legal matters that drew them into parallel had not yet occurred nor had their networks crossed. The same thing was still true at the time of Thomas’s return in the spring of 120673.

Andres’s case began a year later, in 1207, and was pursued through the next four years, but from the comments in his chronicle, Thomas seems to have been at home during this period. All four men-Stephen, Richard, Thomas, and William-may have found themselves at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. Thomas went there accompanying his new abbot and got some privileges confirmed74. Richard was there as bishop of Chichester75. While William mentions the council, his entry is very brief; it is not possible to say that he attended76. On the other hand, his ordinary, the bishop of Thérouanne, does appear on the list of attendees, and William himself now certainly had enough connections to the papal court, so it is quite possible he was present77. However, even if William was at the fourth Lateran council, Langton was in no position to set up friendly meetings among his circle: he was in a world of trouble, under suspension78.

This brings us to what is the most likely place for these two men to have had a conversation about chronicles. In July 1220, after lengthy preparations, Stephen Langton celebrated the translation of Thomas Becket from his original shrine to a newly prepared one. This was a major celebration of a festival intended to take a permanent place on the calendar in England79. It was heavily attended, as many chroniclers reported at the time, not only by English clergy but also by many French clerics. This part of the Chronicle of Evesham, however, does not mention the translation. Yet it is hard to imagine that Thomas, by this time prior to Evesham80, was not present at the translation given that Evesham was under Canterbury’s jurisdiction and Thomas’s old teacher was the archbishop, not to mention the extensive pilgrimage indulgences issued on that occasion81.

Likewise, William does not explicitly say he travelled to England for the translation either, but it was logistically possible for him to have done so, as his chronicle does not suggest he was elsewhere in that year:

In the year of the Lord 1220, there was a solemn elevation of the glorious martyr of Christ, Thomas, the archbishop of Canterbury by Lord Stephen of Canterbury and Lord William, the archbishop of Reims, with Henry, the king of England, who was still a boy, standing nearby and Lord Pandulf, the legate of the Apostolic See, the bishop of Norwich, and many other bishops, both French and English, and also many abbots being present, and prelates of various orders, and also an innumerable multitude of clerics, barons, knights and others from nearly every nation that is under the sun. Pious love of the aforementioned martyr drew all these into his presence, and moreover, the said lord archbishop invited many more with his letters from all regions, and prepared a noble palace, as may still be seen, for their reception, with what marvelous festivity we could say, were we not fearful of exceeding moderation82.

The closing words of the passage, that William might say more, strongly imply his presence. Furthermore, other accounts of this festival, which tend to be quite scanty, do not mention that Stephen sent invitations, although it would have made perfect sense for him to do so. The tradition of friendly relations between Stephen and the monks of Christ Church on one hand, and the monasteries of Saint-Bertin and Andres on the other, not to mention Lanton’s personal acquaintance with William, would make these monasteries likely destinaries of such an invitation83. Stephen himself would have been too busy entertaining the important folk who feasted at the two high tables to do more perhaps than greet William84, but we can certainly imagine Lanfranc or Richard Poore at some time during the festivities making an introduction between two men, who if they did not already know each other, had so much in common85. Adam of Thérouanne had also come for the translation; perhaps his presence stirred some reflection86.

It may seem that I have followed in the steps of Schiller (albeit without his talent) in positing a meeting between two people whose meeting there is no historical record. But let us assume that Thomas and William did meet. Why was their approach unique to these two chronicles? One possibility is the limited circulation of both chronicles. But changes in the way the law was practiced may also explain why other monastic writers did not follow in their footsteps. Both men relied on the advice of legal experts when they brought their cases, but, according to their own accounts, they answered and acted for their monasteries in the curia. From the next century onwards, there was less of a place for lay proctors. Legal cases would be put into the hands of professionals as the law became increasingly complex87. So these texts, in a certain way, represent the end of an era.

This paper has argued that attention to the networks around William of Andres and Thomas of Evesham may explain a resemblance that is otherwise hard to explain. But their connections also reveal how their networks functioned and what they might have meant88. Both Thomas and William, through their writing about their monasteries, produced narratives that helped frame their respective identities through their dynamic relationships with others89. One of the most important relationships for both men was with Innocent III, although this paper does not explore that relationship. For William, in particular, his treatment at the hands of the pope represented a validation of his learning, his competence, and his standing in the world90. How William deployed his relationship with Langton, with Poore, and how Thomas did the same is also clear. Both William and Thomas were accomplished men in their day but were only quite locally remembered, unlike the men who linked them, which tells us something about the way medieval networks worked; they were not only networks of the great and powerful but included people of lesser social or intellectual significance91. Equally interesting is the way in which the players in the drama of Andres were all interconnected: elite circles were seemingly very small. Access to one part of it, one individual, could seemingly open up the whole, if the connector was a powerful enough person. We can see some of the mechanisms of advancement here as well: all three of the judges delegated in Andres’s case became bishops themselves, no doubt in part through the kind of legal activities on display in this story, if not this specific case. And such relationships are characteristic of the way medieval society tended to work92.

Bibliographical references

Printed Sources

FRIEDBERG, Emil Albert (Ed.) - Corpus iuris canonici, vol. 2, Decretalium collectiones. Reprint ed. Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1955.

FRIEDBERG, Emil Albert (Ed.) - Quinque compilationes antiquae nec non collectio canonum Lipsiensis. Reprint ed. Graz: Akademische Druck- U. Verlagsanstalt, 1956.

Gallia christiana, in provincias ecclesiasticas distributa: qua series et historia archiepiscoporum, episcoporum et abbatum regionum omnium quod vetus Gallia complectebatur, Vol. 10. Paris: Typographia regia, 1751.

HAIGNERÉ, Daniel - Les chartes de Saint-Bertin d’après le grand cartulaire de Dom Charles-Joseph Dewitte, Vol. 1. Saint-Omer: H. d’Homont, 1886.

HENRY OF HUNGTINGDON. - Historia Anglorum. Ed. and trans. GREENWAY, Diana. Oxford: Clarendon, 1996.

JOCELIN OF BRAKELOND - The Chronicle of Jocelin of Brakelond Concerning the Acts of Asmaon, Abbot of the Monastery of St. Edmund. Ed. and trans. BUTLER, H. E. New York: Oxford University Press, 1949.

MAP, Walter - De Nugis curialium (Courtiers’ Trifles). Ed. and trans. JAMES, M. R.; revised BROOKE, C. N. L. and MYNORS, R. A. B. Oxford: Clarendon, 1983.

ROBERT OF TORIGNY - Chronique de Robert de Torigni, abbé du Mont Saint-Michel. DELISLE, Léopold (Ed.). Vol. 1. Rouen : Le Brument, 1872.

RUSSELL, Josiah Cox; HEIRONIMUS, John Paul - The Shorter Latin Poems of Master Henry of Avranches Relating to England. Reprint ed. Kraus:New York, 1970.

Thomas of Marlborough: History of the Abbey of Evesham. Ed. and trans. J. Sayers and L. Watkiss. Oxford: Clarendon, 2003.

WILLIAM OF ANDRES - The Chronicle of Andres. Trans. L. Shopkow. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2017.

WILLIAM OF JUMIÈGES - The Gesta Normannorum ducum of William of Jumièges, orderic Vitalis, ad Robert of Torigni, Vol 1. Ed. and trans. VAN HOUTS, Elisabeth. Oxford: Clarendon, 1992.