Rodrigo Ximénez de Rada (1170-1247) is a landmark in Iberian historiography. He stands at the crossroads between medieval compilatory texts and Alfonso X’s huge project on the history of Spain1. Ximénez de Rada started this project late in life: he was almost seventy when he decided to write the Historia de rebus Hispaniae, also known as the Historia Gothica (Díaz 1241)2, which presented a complete narrative of the history of the Iberian Peninsula as a whole from its first inhabitants up to the kingdom of León and Castile. At the same time, it sought to ensure Toledo’s primacy in the peninsula, as the main heir to the Visigothic episcopal see. Georges Martin argued that Ximénez de Rada’s work was a historiographical response to Lucas of Tuy’s Chronicon mundi3. The two men were contemporaries and Lucas’ chronicle certainly worried Ximenez de Rada, because it promoted Seville’s primacy over Spain, instead of Toledo4. The first version of Historia Gothica may have been completed quickly, by the end of April 12435: Ximénez de Rada took about three years to prepare it.

He depended almost entirely on Iberian material. Since Late Antiquity, Iberian historiography had mainly comprised the compilation of pre-existing texts in chronological order, and the addition of new texts to these in order to bring them up to the present6. This was already the case with Hydatius (who continued Eusebius/Jerome’s Chronicon), with John of Biclar (who had added a quire to a codex containing the Chronicon by Victor of Tunnuna), and with the Mozarabic chronicles - the Chronica Byzantio-Arabica continued the text of John of Biclar and the Chronica Muzarabica a. 754 supplemented the Historiae by Isidore of Seville. Likewise, the Chronica Adefonsi III was a continuation of the Historiae; and the Historia Sampiri of the Chronica Adefonsi III.

Important compilations of texts had been in circulation since at least the eighth century. They are at the origin of the manuscripts known as the “Soriensis”7 (perhaps from the tenth century; now lost); the “Rotensis”8, ms. Madrid, BRAH cod. 78 (copied at the end of the tenth century); and the “Alcobaciensis”9, ms. Madrid, Biblioteca Marqués de Valdecilla-Universidad Complutense, 134 (copied after 1250). These transmitted different collections of independent texts, organized in roughly chronological order, allowing a sequential diachronic reading. The most recent examples of this compilation genre were produced in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries: the Liber Chronicorum by Pelagius of Oviedo, the anonymous Chronica Naiarensis and the Chronicon mundi of Lucas of Tuy.

The main objective of this paper is to consider the place of Rodrigo Ximénez de Rada as the heir of this Iberian historiographical tradition whose roots lie in the end of the Roman Empire. I propose to take as a case study Isidore’s Historiae, a component of all of these compilations, to analyze the way in which Ximénez de Rada used it at two levels: in the structuring of his own work and as a source. In terms of structure, I will show how Isidore’s Historiae was the main model for Ximénez de Rada’s own project, and how it was used to structure his text. Concerning the use of Isidore’s text as a source, I will identify which versions of the Historiae were used by Ximénez de Rada, and analyze how, concretely, Isidore’s text was adapted. I will argue that Isidore’s Historiae was the most important model for Ximénez de Rada’s own work; it was also one of Ximénez de Rada’s main sources. However, he did not just copy it, but took Isidore’s structure and text, rethought them and made a completely new work of his own.

Until the time of Rodrigo Ximénez de Rada, the historiography produced in the Iberian Peninsula was notable for its lesser quantity and lesser quality than elsewhere around the Mediterranean basin. After the middle of the fifth century (with Hydatius), one must wait at least a hundred years to find a chronicle worthy of the name (John of Biclar); even in the seventh century, there were only three authors writing history: Maximus of Zaragoza (whose text was lost),10 Isidore of Seville and Julian of Toledo. After the Mozarabic chronicles of the eighth century, one must wait again almost 150 years for a new chronicle, this time in Oviedo, and then again more than a century for the Chronica Sampiri. About the twelfth century, as Peter Linehan remarks, “an English historian of the same period may be forgiven for wondering at the causes of the poverty of the historiographical tradition to which Lucas of Tuy and Rodrigo of Toledo were heirs”11.

However, there was a tradition of sorts: of course, nothing from ancient Greco-Roman historiography ever circulated in the peninsula after the fifth century (and perhaps not even before), but between the fifth and the twelfth centuries, the historiography circulating built, for the most part, on early Iberian texts (the main exceptions are the chronica by Eusebius/Jerome, Prosper of Aquitaine and Victor of Tunnuna)12. The two texts by Isidore of Seville, the Chronicon13 and the Historiae,14 were considered as a kind of canonical model of what “writing history” should mean15. They were not chronologically sequential (they overlapped in chronological terms mainly from the fourth century onwards) and corresponded to two different geographical and ethnic understandings of the past. Despite the shrinking of geographical perspective at the end of the text16, the Chronicon was the heir of the geo-ethnic universalism of the late antique chronicles: after Adam and Eve, it presents the “universal” framework in which all of human history unfolds and with which Iberian history is intertwined. The Historiae, in contrast, has a much more particularistic perspective in terms of geography and ethnicity - it is a chronological narrative about the different peoples who had passed through Iberia from the fifth century onwards. Apart from a historiographical collection firstly produced in Biclar (which came to include the chronica by Eusebius/Jerome, Prosper of Aquitaine, Victor of Tunnuna and John of Biclar and the Chronica Byzantio-Arabica)17, almost all other historiographical texts that circulated in Iberia were related to these two works by Isidore.

The brevity of the Chronicon facilitated its enormous fame throughout Europe18. The Historiae, on the other hand, enjoyed a very small circulation outside Iberia. Its “Iberian character” denied it a similar success. However, this was precisely the reason for its domestic popularity: among all the available texts, the Historiae was the only one that gathered and narrated a history of Iberia up to the Visigothic period. Therefore, for historians who came after the seventh century, the Historiae was the main organized repository of information about the past of both the peninsula and its population (especially once the Christians rulers of the north began to understand themselves as heirs of the Goths).

For this reason, in Asturias at the time of Alfonso III, the central part of the Chronica Albeldensis was formed by the Ordo Romanorum and the Ordo gentis Gothorum, résumés of Isidore’s two texts19. The Chronicon and the Historiae were also copied in the “Soriensis”20, “Rotensis”21 and “Alcobaciensis”22 compilations. As early as the twelfth century, they were also included in the first part of the Liber Chronicorum by Pelagius of Oviedo23, the anonymous Chronica Naiarensis24 and the Chronicon mundi by Lucas of Tuy25. Rodrigo Ximénez de Rada followed in this sequence.

However, in terms of structure, Ximénez de Rada introduced at least two innovations, both involving Isidore’s Historiae: first of all, his text is not a chronicle in the classical sense of the term. Ximénez de Rada completely rejected the spatial universality that had characterized the chronicles that preceded him, based on the distant model by Eusebius of Caesarea26. Ximénez de Rada’s program did not include a long history of the world since Adam and Eve: he planned a history de rebus Hispaniae, universal in time (at least since Japhet, Noah’s son), but particular in space. He therefore did not consider Isidore’s Chronicon but took the Historiae as his model instead. What distinguished the Historiae and the Chronicon was their respective Iberian and universal perspectives and the former is exactly what characterized Ximénez de Rada’s historiographical project. The Historiae consisted of three texts: a larger one on the Goths (in our modern editions with 65 paragraphs), but also two smaller ones on the Vandals and the Suevi (with 14 and 8 paragraphs, respectively). Ximénez de Rada was the first author who sought to replicate Isidore’s project in the Historiae. But his historiographical project was far more ambitious than Isidore’s: he used a much wider set of sources to build a much longer and more detailed text, which included the mythical origins of the Iberian Peninsula’s inhabitants. It included a Historia Gothica (as Isidore had included a Historia Gothorum) but also a set of shorter texts about the other peoples that had inhabited Iberia (not only the Vandals and Suevi): the Historia Romanorum (Díaz 1245), the Historia Ostrogothorum (Díaz 1242), the Historia Hugnorum, Vandalorum, Sueuorum, Alanorum et Silingorum (Díaz 1243) and the Historia Arabum (Díaz 1244). Although the scope was much broader, the principle was the same as in Isidore: to narrate the histories of the peoples who had succeeded the Romans in Iberia (including the Romans themselves).

There was a second important innovation. In Iberia, historiographical compilations were mainly based on parataxis. This means that the compilers usually copied one source after another in a sequence, with limited intervention in the texts. Normally, at the end of the collection, one would add a new text, which brought the compilation up to date: the Liber Chronicorum by Pelagius and the Chronica Naiarensis were organized in this way. Lucas of Tuy’s Chronicon mundi, especially in book 3, had already gone beyond this mere paratactic logic. He combined in a single text information taken from different sources, without copying them in full or, above all, sequentially. However, in the Chronicon mundi, with some occasional exceptions (mainly additions), this was not the approach taken at the beginning of the text, with Isidore’s Chronicon and Historiae (which occupy what are now books 1-2). Lucas of Tuy tended to respect the integrity of the texts of Isidore, an author of unquestionable auctoritas in Iberia and particularly at Saint Isidore of León, where he was writing. This literary respect is no longer a characteristic of the Historia Gothica. Ximénez de Rada preferred not to copy or paratactically use one source after another; much more often than his successors, he combined them, often working together information taken from minor sources27.

In what is the beginning of the Historia Gothica (today book 1.1-19)28, Ximénez de Rada made little use of Isidore’s Historiae: these chapters narrate the period before the Goths’ crossing of the Danube in 376, about which Isidore had very little information. But even in these first chapters, Ximénez de Rada did not forget the Historiae. On the contrary, he used all the meagre information provided by the Historia Gothorum and by Isidore’s so-called Recapitulatio, a very short text (five paragraphs in our editions) that is usually copied with the Historia Gothorum, as a kind of abridgment: he mentions the association Isidore made between the Goths and the Getes, and, through them, the mythical Gog and Magog mentioned in Ezekiel’s prophecy; he also mentions the relationship between the Goths and the Scythae, the etymological interpretation of the word “Goth” as fortitudo, the alliance between Pompey and the Goths against Caesar, the crossing of the Goths into the Iberian Peninsula (with a text taken from the Recapitulatio = Hist. Gothica 1.9) and, finally, the conflicts between the Goths and Claudius II (= 1.10, 1.17) and Constantine (= 1.18).

Still, the main source used for these first paragraphs was not the Historiae but Jordanes’ Getica. This text restructures entire narrative of the “prehistory” of the Goths, where in previous collections Isidore’s Chronicon had usually been the first important text to be copied. The reason for this change is not just the simple desire to replace one text with another. From the moment Ximénez de Rada had access to the Getica by Jordanes, it became essential for his historiographical project to include the extensive information about the origins of the Goths found therein. Isidore did not know Jordanes’ text; nor did any Iberian author before Ximénez de Rada. When the latter decided to write inspired by Isidore’s Historiae, he knew that there was nothing in the Iberian historiography concerning the history of the Goths before 376. This is why Jordanes’ Getica became so important: it transmitted a huge amount of new, even excessively detailed, information about the Goths up to the sixth century, but above all about their “prehistory”. When Ximénez de Rada found this text, the possibility of writing a new narrative based on this new information justified his dismissal of Isidore’s Chronicon as a structuring model, and its replacement by the Getica.

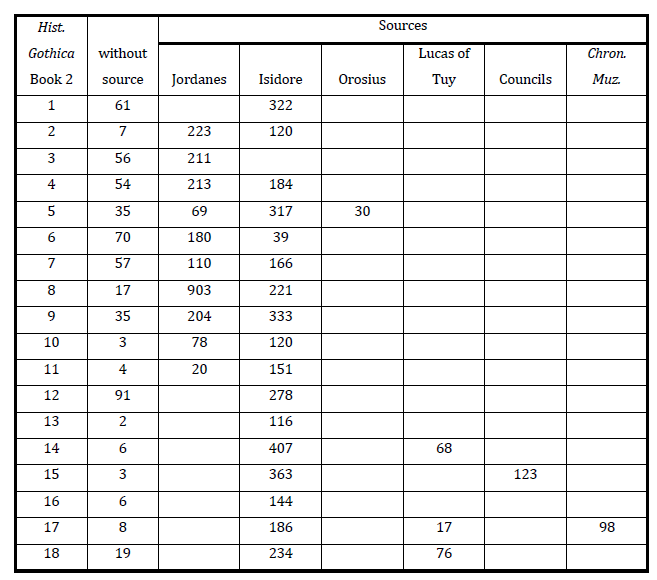

In writing book 2, the situation was not exactly the same. For the history of the Goths from Athanaric (whom Isidore had considered as the primus king of the Goths) up to the sixth century, Ximénez de Rada could have kept Jordanes’ Getica as his main source. However, from this point on, Isidore’s Historiae contained information that could also be used. Ximénez de Rada decided to use these two sources, almost on an equal footing. To get an idea of his use of Isidore’s Historiae in book 2 of the Historia Gothica, I looked at its first 18 chapters. I counted how many words Ximénez de Rada had taken from each of the sources. Of course, the count is not very accurate: on the one hand, Ximénez de Rada rarely copied his source verbatim; secondly, he often synthesized Jordanes’ Getica rather than copying it extensively (as he did with Isidore’s text). The results of this survey are in the table 1 below:

Until chapter 11, on the reigns of Alaricus II and Gesalic, Isidore and Jordanes are used in a reasonably balanced way: clearly Ximénez de Rada had the two texts in front of him and, for each subject, he combined information from both, normally summarizing Jordanes, and copying Isidore’s text more closely (but rarely verbatim). Up to chapter 11, 47.9% of the information collected by Ximénez de Rada is still taken from the Getica; 42.8% from the Historiae. In part, this discrepancy is due to the use of the Getica in the very long chapter 8, on the Huns (Isidore wrote little on the subject). If we exclude this chapter, the values are inverted: 37.7% for the Getica and 50.5% for the Historiae. In any case, there is no clear rule: Ximénez de Rada did not decide to start using the Historiae as a main source and the Getica as a secondary source. He relied more heavily on one or the other according to circumstances: on Athanaric and the Arian heresy, he used only Isidore (ch. 1), but on the peace between the Romans and the Goths after the battle of Adrianopolis, he used Jordanes exclusively (ch. 3); for the sack of Rome and for the reigns of Euric, Alaric II and Gesalic, he clearly favored Isidore (chs. 5, 10-11); for Athaulf’s reign he preferred Jordanes (ch. 6).

Still, exclusive use of a single author is rare. This only changes after chapter 11. From this point, Ximénez de Rada seems to have lost interest in the Getica even though Jordanes covered the Visigoths up to king Athanagild. In fact, at this point, Jordanes’ focus turns to Italy and the Visigoths clearly became a secondary concern. Hence, for chapters 12-18, the Historia Gothorum takes on the role of primary source that the Getica had played in much of book 1: 77% of the material comes from Isidore’s text. Yet Isidore’s Historiae is rarely the sole source. For the Third Council of Toledo, Ximénez de Rada used information taken from the conciliar Canones (ch. 15); and he also used information from the Chronica Muzarabica a. 754 (which circulated with Isidore’s Historiae as its continuation) and from Lucas of Tuy’s Chronicon mundi.

For the Historiae minores, the picture is different. On the one hand, Ximénez de Rada’s investment in these texts was smaller; on the other, here was also less information available. Isidore’s Historiae was also, of course, the main source for the Vandals and the Suevi. However, Isidore also had little to say on the history of the Vandals before their arrival in the Iberian Peninsula: the Getica was still the preferred source here. Ximénez de Rada used Isidore’s Historia Wandalorum for a few references to the crossing of Gaul (chs. 3-4), but it eventually became his main source (chs. 5-10), above secondary texts as the Historia Romana by Paul Deacon (another text not previously known in Iberia; chs. 7-8) and, very occasionally, the Chronicon by Prosper of Aquitaine (ch. 7). For the Suevi (chs. 12-15), Isidore’s Historia Sueuorum is the only source used by Ximénez de Rada (it is curious that he did not use Hydatius’ Chronicon, which circulated in the “Alcobaciensis” collection).

Where did Ximénez de Rada read Isidore’s Historiae?

Ximénez de Rada’s library was not necessarily extensive: the sources he used are the best clue to what was available in Toledo’s library: Orosius’ Historiae (CPL 571), Prosper’s Chronicon (CPL 2257), Isidore’s Historiae (CPL 1204), the Chronica Muzarabica (Díaz 397), the Cronica del moro Rasis, the Chronica Adefonsi III (apparently in both versions - Díaz 519, 520), the Chronica Sampiri (Díaz 889), the Chronica Silensis (Díaz 888), the Historia Roderici (Díaz 883), Pelagius of Oviedo’s Chronicon (Díaz 901), the Chronica Naiarensis (Díaz 996), Lucas of Tuy’s Chronicon mundi (Díaz 1226).

Ximénez de Rada also had some texts not previously known in Iberia: Jordanes’ Getica (CPL 913) was one and, as Helena of Carlos Villamarín has convincingly argued, probably some paraphrases or resumés of the Excidium Troiae, the Exordia Scythica and Paul the Deacon’s Historia Romana, close to those which are found today in ms. Bamberg Hist. 329.

This does not imply the existence of many codices, since several of these texts circulated together: Prosper’s Chronicon, Isidore’s Historiae and the Chronica Adefonsi III were copied in the “Soriensis” compilation mentioned above; Orosius’ Historiae, Isidore’s Historiae and the Chronica Adefonsi III in the “Rotensis” compilation; Orosius’ Historiae, Prosper’s Chronicon, Isidore’s Historiae and the Chronica Muzarabica in the “Alcobaciensis” compilation; Isidore’s Historiae, the Chronica Adefonsi III, the Chronica Sampiri and Pelagius of Oviedo’s Chronicon in Pelagius’ Liber Chronicorum; Isidore’s Historiae, the Chronica Adefonsi III, the Chronica Sampiri, Pelagius’ Chronicon and the Historia Roderici were part of the Chronica Naiarensis. Lucas of Tuy included Isidore’s Historiae, and excerpts from the Chronica Adefonsi III, the Chronica Sampiri, the Chronica Silensis and Pelagius of Oviedo’s Chronicon30. Only the Latin version of the Crónica del moro Rasis was not copied in any of the collections listed above.

Ximénez de Rada did not need to have all these collections, for as we can see, they transmitted the same texts in many cases. Fernández Valverde argued that he certainly had the Liber Chronicorum by Pelagius, the Chronica Naiarensis and the Chronicon mundi. We may be able to assume that he used the Chronica Muzarabica from some codex containing the “Alcobaciensis” collection; the “Rotensis” version of Chronica Adefonsi III (which he also used) may also indicate some familiarity with the “Rotensis” collection. Finally, Ximénez de Rada used a codex of Italic origin, containing texts of extra-Iberian circulation, including Jordanes’ Getica. In any case, we are counting with only about half a dozen codices, many of them containing the same texts: it is not necessary to imagine many manuscripts.

Considering the Historiae, Fernández Valverde argued that Ximénez de Rada would have used some manuscripts related to L (the Chronicon mundi by Lucas of Tuy), to H (the Chronica Naiarensis) and to MA (manuscripts representing the “Alcobaciensis” compilation)31. More recently, Francisco Bautista argued that the manuscript used by Ximénez de Rada was close to one from Seville, copied at the end of the sixteenth century (C), and that it depended on the same archetype as MA32.

Isidore’s Historiae has come down to us in two different versions: a shorter, transmitted only by two manuscripts and one copy (twelfth-fourteenth c.); and a longer, with a more complex transmission. The longer version is the only one to have an indirect tradition. At least four different families can be distinguished:

α. the oldest known manuscript (B: Berlin, Phillipps 1885) represents the Carolingian edition of the Historiae33. This was the only version in circulation outside Iberia until the end of the Middle Ages. It had a very limited transmission, however: it was copied in the scriptorium of Pacificus of Verona, before 840, and did not circulate outside northern Italy before the end of the Middle Ages. This is not a unique case: very little of the early medieval Iberian historiography crossed the Pyrénées.

β. The text that was copied in the “Soriensis” collection depended on this model34. The version copied in the Liber chronicorum by Pelagius of Oviedo (the main representative is Ms. G = Madrid, BN 1513, with several copies)35 and in the Chronicon mundi by Lucas of Tuy also depends on this branch of the tradition.

γ. This branch includes the text that circulated in the “Rotensis” collection at the end of the tenth century. The main representative is ms. R = Madrid, BRAH, cod. 7836.

δ. This is the branch of the “Alcobaciensis” compilation. Its main representatives today are mss. M = Madrid, Complutense 134; K = København AM 833 4º; and C = Sevilla, Colombina 58-1-337.

In Rodrigo Ximénez de Rada’s time, three of these versions were circulating in the Iberian Peninsula: only the Carolingian edition was not known. These three versions were copied in the three main early medieval compilations mentioned above (“Soriensis”, “Rotensis” and “Alcobaciensis”). When Ximénez de Rada was writing, the “Soriensis” manuscript was already extant and somewhere between Castile and Rioja. In Toledo there was a manuscript with the Liber chronicorum by Pelagius of Oviedo, copied between 1210-1220 (ms. G), and a copy of the Chronicon mundi by Lucas of Tuy (all derived from β). In the northeast, ms. R was probably already in the library of the Cathedral of Roda de Isábena (Huesca), where it was kept until 1699; at least one copy of this “Rotensis” text, probably made in Aragon (today Ms. Madrid, BN 8831), had also been copied at the end of the eleventh or early twelfth century (derived from γ). The “Alcobaciensis” was already shelved in the Portuguese monastery of Alcobaça; a copy or a twin manuscript may already have been available in Toledo, where the ms. Complutense 134 was copied after 1250 (derived from δ).

To these three “Iberian” versions, I also add the Chronica Naiarensis (ε), copied, according to Alberto Montaner Frutos, between 1190 and 119438. The copy of Isidore’s Historiae included in the Chronica Naiarensis is a text contaminated by several different versions: its main model is the text copied in R (γ); the author of the Chronica Naiarensis also used some notes taken from a copy of the “Soriensis” collection (β)39.

Considering the codices available in his time, Ximénez de Rada’s library could have held all the versions of the Historiae circulating in Iberia: β, in the compilations by Pelagius of Oviedo and Lucas of Tuy (Ximénez de Rada used both); ε, with the copy included in the Chronica Naiarensis; maybe γ (“Rotensis”); and δ (“Alcobaciensis”). For the purposes of this paper, the high positions of the stemma and the relationship between all these branches are not important; the question of the double recension is also irrelevant40. Above all, I am interested in analyzing which texts were in Ximénez de Rada’s library when he needed sources for his own work.

There is a problem with this inquiry: Ximénez de Rada did not copy ipsis uerbis Isidore’s Historiae. Unlike his predecessors, he used extensive parts of the Historiae, but often in synthesized form, and he very often used it only as a basis from which to write a new text of his own: it is still possible to recognize Isidore’s text, but it is also clear that Ximénez de Rada made it his own. Therefore, there are several places when it is not possible to be sure of the version used by Ximénez de Rada.

There are some things we can say with certainty, however. First, it is possible to conclude that, even if he had a copy of γ, he did not use it. The Historia Gothica does not share any of the major errors or variants of γ41. Next, we can see that it is with δ (M K C) that Ximénez de Rada’s text shares the greatest number of variants and errors:

hist. Gothica 1.9.4642occidentis) septentrionis δ septentrionalia iuga Ra

hist. Gothica 1.9.47 post inhabitantes) circa scitica regna δ scithica regna Ra

hist. Gothica 1.9.63 gaius caesar rel. gaius iulius cesar δ iulium cesarem Ra

hist. Gothica 1.10.14 annos rel. annis δ Ra

hist. Gothica 2.1.7 quia rel. qui δ Ra

hist. Gothica 2.1.38 patri rel. patris δ Ra

hist. Gothica 2.4.30 ragadaisus rel. radagaisus δ radagaysus Ra

hist. Gothica 2.5.20 sacra hosti α sacram hostiam δ Ra sacra hostia β γ

hist. Gothica 2.7.2 post Athaulfum) post obitum athaulfi δ Ra

hist. Gothica 2.7.32 grauissima) grauissime δ Ra

hist. Gothica 2.8.17-19 extincto igitur litorio (+ et receptis epistolis ualentiniani Ra) pace deinde theuderedus cum romanis inita denuo aduersus ugnos δ Ra

hist. Gothica 2.9.20 praesidioque suorum) presidioque sueuorum δ Ra

hist. Gothica 2.10.8 regressus) reuersus δ Ra

hist. Gothica 2.12.6 post XVII) menses/mensibus V δ Ra

hist. Gothica 2.12.32 post conclusum) ignauum atque inermem exercitum δ inhermem Ra

hist. Gothica 2.14.5 poposcerat) poposcit δ Ra

hist. Gothica 2.14.31 post potitus) ampliauit δ Ra

hist. Gothica 2.17.2 post Sisebutus) christianissimus δ C rex christianissimus Ra

hist. Gothica 2.17.22-23 post inbutus) in iudiciis iustitia et pietate strenuus ac prestantissimus mente benignus splendore regni precipuus δ in iudiciis strenuus ac prestantissimus pietate mente benignus gubernatione regni precipuus Ra

hist. Gothica 2.17.29-31 post subiecit) residuas intra fretum omnes exinaniuit quas gens gothorum post in ditionem suam facile redegit (in suam redegit facile ditionem Ra) δ Ra

hist. Gothica 2.17.35 post haustu) alii ueneno δ Ra

hist. Gothica 2.17.35-36 post interfectum) cuius exitus non modo (solum Ra) religiosis sed etiam obtimis laicis immodice (om. Ra) extitit luctuosus δ Ra

As Bautista recognized, within δ, Ra shares some errors only with C43:

hist. Gothica 1.9.63 gaius caesar rel. gaius iulius cesar δ iulium cesarem Ra iulius caesar C

hist. Gothica 1.17.26 post remouisset) insigni gloria honorantes Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.1.33 ebibit rel. bibit Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.2.32 (cf. Isid. Goth. 9). Uiuens) om. Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.4.4 post tradiderunt) fueruntque cum Romanis XVIII/XXVIII annis C fueruntque sine rege XXVIII annis Ra

hist. Gothica 2.8.21 Catalaunicis rel. cathalanicis Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.12.43 post I) menses/mensibus tres Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.14.19 statuit rel. instituit Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.16.5 regno rel. regem Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.18.17-18 (cf. Isid. Goth. 63) obsides darent rel. om. Ra C

hist. Barb. 6.20 erbasis rel. neruasis Ra nerbasis C

hist. Barb. 9.11-12 ad finem rel. in finem Ra C;

hist. Barb. 12.13 andeuotum rel. andebodem Ra C

hist. Barb. 15.3 XIII rel. III Ra C

C is a sixteenth-century manuscript: the watermark on its paper is from 158244. In addition to the Historiae, it also transmits the Chronica Muzarabica, whose text, although highly contaminated45, is very close to the one copied by Juan Bautista Pérez in his codex Segobrigensis (second half of the 16th. c.)46. Gil and Bautista defend that Pérez had copied the Chronica Muzarabica from a lost codex from Burgo de Osma (Soria), which transmitted the “Alcobaciensis” collection47. Therefore, the Historiae copied in C could also depend on this same manuscript. Furthermore, Ximénez de Rada was briefly bishop of Burgo de Osma (1208-1209) before going to Toledo: the possibility that he came into contact with a codex from this city is high. However, he cannot have used the codex from Burgo de Osma directly, since, despite their proximity, regarding Isidore’s Historiae, Ra does not share most of C’s errors48. Nevertheless, the manuscript seen by Ximénez de Rada and that of Burgo de Osma certainly depended both on the same model.

Within δ, Ra only shares three of the errors and variants common to M K:

hist. Gothica 2.11.21 flumen rel. C fluuium M K Ra

hist. Gothica 2.15.22 fere rel. C ferme M K Ra

hist. Gothica 2.17.2-3 regali fastigio rel. C ad regale fastigium M K Ra

Ra also shares some errors unique to K:

hist. Gothica 2.2.5 non depositis armis rel. depositis armis K armis depositis Ra

hist. Gothica 2.10.22 post speciem) uidit K Ra

hist. Gothica 2.10.23 instituta rel. statuta K Ra

hist. Gothica 2.11.10 narbona rel. narbone K Ra

hist. Gothica 2.12.28 eundemque rel. idemque K et idem Ra

hist. Gothica 2.12.31 adgressum rel. aggressi K agressi Ra

hist. Gothica 2.12.40 post dicens) se K Ra

hist. Gothica 2.15.29 ubi rel. unde K Ra

hist. Gothica 2.15.30 utilitatis rel. certaminis K Ra

hist. Gothica 2.18.13 post uirtute) prelii K prelio Ra

K is a factitious manuscript on paper, collecting a very diverse set of texts copied by different hands. As Bautista has shown49, it is a working manuscript owned by Juan Páez de Castro (c. 1510-1570), royal chronicler of Felipe II (1527-1598). Its Part II transmits the Historiae among several texts from the “Alcobaciensis” collection. It was copied “on October 14, 1562” (“XIV de Xbre de 1562”; f. 165r).

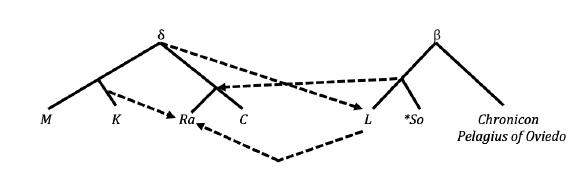

Therefore, Ra and MKC depend on a common archetype (δ). Within δ, Ra and C depend on the same model; however, Ximénez de Rada had some notes taken from a manuscript close to the model of K.

A manuscript derived from δ was also used by Lucas of Tuy50 and by the author of the Chronica Naiarensis (= ε; I note only the coincidences with Ra):

hist. Gothica 1.9.46 Occidentis rel. septentrionis δ ε C septentrionalia iuga Ra

hist. Gothica 1.9.47 post inhabitantes) circa scitica regna δ ε C scithica regna Ra

hist. Gothica 1.9.63 gaius caesar rel. gaius iulius cesar δ iulius cesar L Ra C

hist. Gothica 1.10.14 annos rel. annis δ ε L Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.1.7 quia rel. qui δ L Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.1.38 patri rel. patris δ Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.7.2 post Athaulfum) post obitum athaulfi δ L Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.9.20 praesidioque suorum rel. presidioque sueuorum δ ε RaC

hist. Gothica 2.10.8 regressus rel. reuersus δ ε RaC

hist. Gothica 2.12.6 post XVII) menses/mensibus V δ L Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.12.32 post conclusum) ignauum atque inermem exercitum δ L C inhermem Ra

hist. Gothica 2.14.5 poposcerat rel. poposcit δ ε Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.17.2 post Sisebutus) christianissimus δ ε C rex christianissimus Ra

hist. Gothica 2.17.22-23 post inbutus) in iudiciis iustitia et pietate strenuus ac prestantissimus mente benignus splendore regni precipuus δ ε C in iudiciis strenuus ac prestantissimus pietate mente benignus gubernatione regni precipuus Ra

hist. Gothica 2.17.29-31 post subiecit) residuas intra fretum (in transfretum ε) omnes exinaniuit quas gens (gentes ε) gothorum post in ditionem suam facile redegit (redegerunt ε in suam redegit facile ditionem Ra) δ ε Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.17.35 post haustu) alii ueneno δ ε L Ra

hist. Gothica 2.17.35-36 post interfectum) cuius exitus non modo (solum Ra) religiosis sed etiam obtimis laicis immodice (om. K Ra) extitit luctuosus δ ε Ra C

This means that δ is at the origin of the MK and RaC subgroups, and that a manuscript dependent on δ was used by the Chronicon mundi (L) and the Chronica Naiarensis.

There are also errors that indicate a contamination between the model of RaC and β, and quite possibly with some representative of the model of the “Soriensis” manuscript (*So) and L:

hist. Gothica 1.17.26 post remouisset) insigni gloria honorantes *So L Ra C

hist. Gothica 2.4.4 post tradiderunt) fueruntque cum Romanis XVIII/XXVIII annis β C fueruntque cum Romanis septem annis L fueruntque sine rege XXVIII annis Ra

hist. Gothica 2.12.43 post I) menses/mensibus tres β Ra C

hist. Barb. 4.9 proterunt rel. prosternunt β C prostrauerunt Ra

Ximénez de Rada also used a manuscript with the Chronicon mundi by Lucas of Tuy (L). They share many unique variants:

hist. Gothica 2.7.38 data) dataque est L et data est Ra

hist. Gothica 2.9.49-50 post constituent) qui regnauit duobus annis L qui tantum duobus annis regnauit Ra

Maldra autem tertio regni anno a suis iugulatur) om. L Ra

hist. Gothica 2.13.15 milites rel. extranei milites L Romani milites Ra

hist. Gothica 2.14.14-16 qui cum primo christianus haberetur teodosiam filiam seueriani ducis cartaginensis filii regis teoderici duxit uxorem ex qua hermegildum et recaredum filios sucepit L duxerat autem leouegildus uxorem nomine theodosiam filiam seueriani ducis prouincie cartaginensis qui fuerat filius regis theuderici Ra

hist. Gothica 2.14.18 DCVI rel. DCX L Ra

hist. Gothica 2.14.22 omnis) om. L Ra

hist. Gothica 2.14.26 exsuperauit rel. hispali dolo cepit L Ra

hist. Gothica 2.14.26-29 beatum ermegildum filium suum nefandis ritibus communicare nolentem diuersis tormentis prius excruciatum denique in uinculis positum dira secure interficere iussit et dignum deo martirem illius feralis crudelitas consecrauit L et quia nephandis ritibus noluit consentire tormentis uariis cruciatum demum securi percussum parricida impius dignum deo martyrem conscrauit Ra

hist. Gothica 2.14.55-59 sed antequam moreretur precepit filio suo recaredo ut beatum leandrum archiepiscopum yspalensem ab exilio reuocaret et eum audiret ut patrem et in fide Christi confirmaretur. tunc temporis fulgentius astigitanus episcopus in nostro dogmate claruit L set dum infirmitate acriter torqueretur precepit filio recharedo ut episcopos ab exilio reuocaret et leandrum hispalensem et eius germanum fulgencium astigitanum qui in doctrina ecclesiastica fulgebat insignis tanquam patres audiret et eorum monitis obediret Ra

hist. Gothica 2.15.2 DCXXIIII rel. DCXXVIII L Ra

hist. Gothica 2.15.17 in deum rel. in uno deo L unum deum Ra

hist. Gothica 2.15.23 ante duce) emeritensium L emeritensi Ra

hist. Gothica 2.16.3 DCXXXVIIII rel. DCXLIII L Ra

hist. Gothica 2.17.27 ecclesiam sancte leocadie toleto prefatus princeps miro opere fundauit L ecclesiam sancta leocadie toleti miro opere fabricauit Ra

hist. Gothica 2.17.36-38 ipso tempore mahumet ab yspania turpiter fugatus in affrica nequiciam nefarie legis stultis populis predicauit L huius temporibus nephandus Mahomat nequiciam secte sue stultis populis predicauit Ra

hist. Gothica 2.18.3 post sceptra) qui regnauit annis decem L et regnauit annis X Ra

hist. Gothica 2.18.25-26 post dignus) fine proprio toleto decessit L toleti propria morte decessit DCLXXIII Ra

None of these errors and additions appears in C: hence, these differences result from the direct consultation of L by Ximénez de Rada.

In summary, Ximénez de Rada used a manuscript dependent on the “Alcobaciensis” collection (δ). This model probably had some marginalia taken from a manuscript dependent on β. At the same time, he decided to systematically collate the text of Isidore’s Historiae included by Lucas of Tuy in his Chronicon mundi. Ximénez de Rada was mainly concerned with the new information that Lucas had added, and not so much with the minor variants introduced by Lucas in Isidore’s text. Regarding Isidore’s text, Ximénez de Rada’s Historia Gothica and Historiae minores do not share any important variant exclusive to either the Chronica Naiarensis or the Chronicon by Pelagius of Oviedo. Therefore, this is a possible stemma:

I still want to take a final step to argue that Ximénez de Rada was indeed a fine historian and that he was exercising editorial judgement in his use of sources. His complex method of composition reveals it.

As noted above, Isidore became a central and often the unique source only after Athanaric. However, the Historiae had already been used before. The following excerpt may illustrate Ximénez de Rada’s method. In italics, we have the text taken from Jordanes’ Getica, in bold that from Isidore’s Historia Gothorum and in Roman the new text inserted by Ximénez de Rada (comments or information without a known source).

Hec que diximus de gentis Gothorum principio Abauius descriptor gentis Gothorum egregius uerissima hystoria atestatur, in quam sentenciam multi de maioribus consenserunt. Iosephus quoque annalium relator uerissimus, qui ueritatis regulam et causarum origines retexit fideliter, et Ysidorus Gothice gentis indigena et cronicorum disertor optimus hec que diximus de Gothorum principio cur omiserint ignoramus. Set tantum ab hoc loco eorum prosapiam memorantes, Iosephus Scithas, Ysidorus Gethas asserunt appellatos. Set cum de eorum antiqua origine opiniones uarie habeantur, plus occultat uarietas quam declaret. Iosephus dicit de Magog filio Iaphet Scithas, qui et Massegetes, processisse. Vnde quidam nituntur ea que Ezechiel propheta contra Gog et Magog spiritualiter prophetauit Gothorum actibus adaptare. Isidorus doctor, nullius sciencie expers, eos Getharum siue Scitharum docet ex genere processisse, et e littera mutata in o Gethe dicuntur Gothi. De quibus poeta: Mortem contempnunt laudato uulnere Gethe. Set Iosephus et Ysidorus, quia ortum eorum a Schancia omiserunt, Scithas et Gethas ab incolatu patrie, non ab origine appellarunt. Hii septentrionalia iuga temptantes, Scithica regna montibus ardua possederunt. Et pars illa adhuc hodie Gothia appellatur. Interpretatio autem nominis eorum in lingua nostra fortitudo, et re uera; nullius enim gentis strenuitas ita regnis et imperiis se obiecit. In primo enim egressu a Schancia gentem stolidam Vlmerrugorum et Wandalorum a suis sedibus eiecerunt, iuga Scithica subiecerunt, Vesosum regem Egipti prelio fugauerunt, Asiam subiugarunt et eorum aliqui inibi remanserunt, ex quibus Parthi, ut dicitur, processerunt. Horum femine relicte a uiris armis in preliis claruerunt et partem Asie subiecerunt, Armeniam, Siriam, εiliciam, Galaciam, Pisidiam, Yoniam et Eoliam domuerunt. Thelephus rex Gothorum uicit Danaos, interemit Thessandrum, insecutus fuit Vlixem; εirus famosus a Thamari regina Gothica fuit occissus. Darius filius Ydaspis et filius eius Xerses ab Ancyro rege Gothorum inferiores in prelio sunt inuenti. Hos Alexander uitandos docuit, Pirrus pertimuit, Cesar exorruit. Cum Pompeius pro arripiendo reipublice principatu contra Iulium Cesarem arma mouit, et isti ceteris forcius dimicarunt. Thraciam irruerunt, Ytaliam uastauerunt, Romam ceperunt, Veronam hedificarunt nomen imponentes, quasi ue Roma in odium Romanorum, Gallias sunt aggressi, Hyspanias sunt adepti, ibique apud Toletum sedem uite et imperii locauerunt. (hist. Goth. 1.9.27-68)

We are in the “prehistory” of the Goths here. Ximénez de Rada used Jordanes’ text for the geography of “Schancia”, the Goths allegedly homeland, and for their first kings. At some point, Jordanes referred to his own sources, wondering why some Josephus (not the author usually known as Flavius Josephus) had not transmitted much on the origins of the Goths (Get. 4.28-29). Ximénez de Rada also decided to record this doubt and added that he himself did not know why Isidore had no concrete information on the subject either. Then he returned to Jordanes’ text, to add Josephus’ only reference to the Goths’ origins: that they were also called Scythians (Get. 4.29). Then he turned again to Isidore, who recorded that the Goths were also known as the Getae (Isid. Goth. 1; Recap. 66). The following reference to the Massegetes did not come from Jordanes or Isidore. This people had been mentioned by Augustine of Hippo, in the De ciuitate Dei (20.11), where he had affirmed that “some suspect that Gethas et Massagethas derive from Gog and Magog”. These two peoples were mentioned in the Bible as God’s instrument to punish Israel (Ezekiel 38, 1-17). This Augustinian text is probably the passage Ximénez de Rada was thinking of, because he promptly also referred to the relationship between the Goths and Gog and Magog, mentioned by Isidore (Isid. Goth. 1; Recap. 66; Isidore’s source is probably also Augustine). In the Recapitulatio, Isidore also gave more detail, used by Ximénez de Rada to explain the etymological relationship between Getae and Gothi (Recap. 66). The phrase mortem contempnunt laudato uulnere Gethe from an unknown is also taken from Isidore’s Recapitulatio (Recap. 67). After a short commentary, Ximénez de Rada added new information from the Recapitulatio (66: hii septentrionalia …) and a new note of his own. Then, a new combination of information from different sources: the etymological interpretation of Gothi as fortitudo is taken from the beginning of the Historia Gothorum (Isid. Goth. 2); the journey of the Goths from Schancia to the confrontation with the Persians is a summary of Jordanes’ much more extensive text (4.26-27; 6.47; 7.51; 9.59-60; 10.61-64). After this, Ximénez de Rada referred to Pompey, using the Historia Gothorum (3). Then he added a passage, whose origins are unknown, about the Gothic origins of Verona51, ending with a new excerpt from the Recapitulatio, on the crossing of the Goths into Spain (Recap. 66).

As a rule, Ximénez de Rada chooses a main source that he pairs with a secondary source. In this case, the main source is still Jordanes’ Getica; Isidore’s Historiae is used for supplementary information. However, this is rarely a paratactic use; Ximénez de Rada must have had both codices in front of him and combined material from them as he saw fit: he began by referring to the sources (as Jordanes did), then the peoples identified as their supposed ancestors (with material from Jordanes, Isidore and Augustine), the journey of the Goths from their encounters with the Greeks, Persians and Romans to their arrival in Iberia (combining material from Jordanes and Isidore). In this way, he composed a summary of the history of the Goths from their “ethnic” origins to Iberia.

I add a final example:

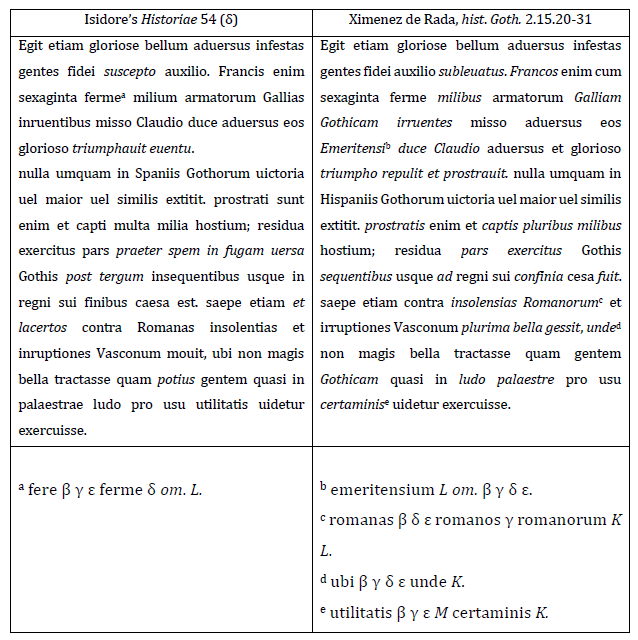

For Reccared’s reign, the only source was Isidore’s Historiae. In the right-hand column is Isidore’s text as it was probably copied in δ. Are additions, omissions or transformations of the text. I point out the variants that Ximénez de Rada may have found in other manuscripts.

One can find different types of change:

Syntactic changes: suscepto > subleuatus; Francis irruentibus > Francos irruentes; sexaginta milium > sexaginta milibus; prostrati sunt enim et capti multa milia > prostratis enim et captis pluribus milibus; in finibus > ad confinia

Morphological changes: caesa est > cesa fuit

Lexical changes: suscepto > subleuatus; glorioso triumphauit euentu > glorioso triumpho repulit et prostrauit; multa > pluribus; insequentibus > sequentibus; finibus > confinia; lacertos mouit > plurima bella gessit; utilitatis > certaminis

Changes in word order: misso Claudio duce aduersus eos > misso aduersus eos duce Claudio; pars exercitus > exercitus pars; Romanorum insolentias > insolensias Romanorum; palestrae ludo > ludo palestre

Additions: Gallias > Galliam Gothicam; duce > Emeritensi duce; gentem > gentem Gothicam

Deletions: praeter spem in fugam uersa; post tergum; potius

I purposely chose a passage in which Ximénez de Rada did not introduce relevant information of his own. This excerpt represents his “normal” usage of Isidore. My first observation is that, although he closely followed Isidore’s text, he modified it significantly. He added the adjective Gothicam to Galliam and gentem, which above all suggests clarification of the text, especially for a thirteenth-century reader. The addition of Emeritensi must depend on Lucas of Tuy’s Chronicon mundi; and certaminis is probably taken from a manuscript close to the model of K. There is an already quite widespread morphological change (the construction of the perfect passive tense with fuit). Most changes are, however, simple syntactic and word-order modifications, corresponding to questions of stylistic variety. Ximénez de Rada rarely suppressed concrete information from the Historiae (Pelagius of Oviedo, the anonymous compiler of the Chronica Naiarensis and Lucas of Tuy did not do so either) or altered the order of events. Like its predecessors, he sought to preserve Isidore’s text, but nevertheless introduced some variation that, while maintaining the information and a good part of the lexicon and grammar, allowed for some creativity.

Ximénez de Rada stands at the end of a long tradition of chroniclers in Iberia who took their model from historiographical collections that circulated in the region at least from the Visigothic and early Mozarabic period. Even when they included earlier texts such as the chronica of Eusebius/Jerome, Prosper of Aquitaine, Victor of Tunnuna and John of Biclar, these compilations almost always maintained Isidore’s Chronicon and Historiae as their essential foundation. However, when Ximénez de Rada decided to undertake his historiographical project, probably as a reaction to Lucas of Tuy’s Chronicon mundi, he did it in a different way to his predecessors; and in doing so he created a different kind of history that already prepared the ground for Alfonso X.

It was a difficult task to step out from tradition, though. In terms of structure, Ximénez de Rada did not have much latitude for creativity: he did not have very different sources from Lucas; nor did he have many important new models, Jordane’s Getica excepted. He decided to take on the model of Isidore’s Historiae and to write a set of histories about the peoples who had passed through Iberia (including the Romans), centered on the Goths and the Christian Iberian kingdoms of the north as their direct and legitimate successors.

The Historiae did not just provide the overall idea for Ximénez de Rada’s project. It was also one of his main sources. Again, he wanted to innovate. Instead of building his work by paratactic compilation of existing texts, he organized his content by juxtaposing and combining different sources whenever he had more than one for the same period or event. Normally, he chose a primary source to which he added new elements gathered from other texts. For the beginning of the Historia Gothica, up to the end of the century, his main source was Jordanes’ Getica: due to its length, he often chose to summarize it. Isidore’s Historiae only complemented this with some scattered information. The beginning of the sixth century, the Historiae became his main and often only source until the reign of Suinthila (up to 625-6).

Ximénez de Rada read the Historiae from a codex transmitting the so-called “Alcobaciensis” compilation, a collection of historiographical texts that circulated in the south of the Iberian Peninsula and whose origins go back to the Visigothic-Mozarabic period. It is possible that this text already had some marginalia taken from other manuscripts. Ximénez de Rada also decided to complete some of the information with the Chronicon mundi by Lucas of Tuy. Although Ximénez de Rada made extensive use of Isidore’s text, his quotation is rarely verbatim: without altering Isidore’s information, he inserted lexical, syntactic and word order variants to the text of the Historiae, aiming at uariatio. A reader who would have known the Historiae would certainly recognize Ximénez de Rada’s debt to Isidore. However, one could not have failed to acknowledge that he had not simply copied and slightly adapted the text as his predecessors had done: Ximénez re-wrote the text, making it his own.

Bibliographical references

Sources

Manuscript sources

Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Hist. 3

Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Phillipps 1885

København, Det Arnamagnaeanske Institut, Københavns Universitet, AM 833 4º

Madrid, Biblioteca de la Real Academia de la Historia, cod. 78

Madrid, Biblioteca Marqués de Valdecilla-Universidad Complutense, 134

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, 1513

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, 8831.

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal 982

Roma, Biblioteca Vallicelliana, R 33.

Sevilla, Biblioteca Capitular y Colombina, ms. 58-1-3

Printed sources

Chronica Hispana saeculi XII. Pars I. Historia Roderici vel Gesta Roderici Campidocti Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Medievalis (CCCM) 71. Turnhout: Brepols, 1990.

Chronica Hispana. Saeculi XII. Pars II. Chronica Naierensis. Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Medievalis (CCCM) 71A. (Ed.) ESTÉVEZ SOLA, Juan Antonio Turnhout: Brepols, 1995.

Chronica Hispana saeculi VIII-IX. Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Medievalis (CCCM) 65. Turnhout: Brepols 2018.

Chronica Hispana saeculi XII. Pars III. Historia Silensis. Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Medievalis (CCCM) 71B. Turnhout: Brepols, 2018.

HISPALENSIS, Isidorus - Chronica. Corpus Christianorum. Series Latina (CCSL) 112. MARTÍN- IGLESIAS, José Carlos). Turnhout: Brepols, 2003.

HISPALENSIS, Isidorus - Las historias de los Godos, Vandalos y Suevos de Isidoro de Sevilla. Estudio, edición critica y traducción. RODRÍGUEZ ALONSO, Cristóbal (ed.). León: Centro de Estudios e investigación “San Isidoro”, Archivo histórico diocesano, Caja de Ahorros y Monte de Piedad de León, 1975.

MOMMSEN, Theodor - Chronica minora. Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Auctores antiquissimi (MGH Auct. Ant. chron. min.) 9. Berolini: apud Weidmannos, 1892.

TUDENSIS, Lucas - Chronicon mundi. Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Medievalis (CCCM) 74. REY, Ema (ed.). Turnhout: Brepols, 2003.

OROSIUS, Histoire contre les Païens, 3 vols. LINDET, Marie-Pierre (ed.). Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1991.

TIRO, Prosper - Chronik. Laterculus regum Vandalorum et Alanorum. Kleine und fragmentarische Historiker der Spätantike (KFHist) G5. BECKER, Maria; KöTTER, Jan-Markus (eds.). Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2016.

Ximénez de Rada, Rodrigo - Opera Omnia I. Historia de rebus Hispanie siue Historia gothica. FERNÁNDEZ VALVERDE, J. (ed.). Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Medievalis (CCCM) 72. Turnhout: Brepols, 1987.

Ximénez de Rada, Rodrigo - Opera Omnia III. Historiae minores. Dialogus libre uitae. FERNÁNDEZ VALVERDE, Juan (ed.). Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Medievalis (CCCM) 72C. Turnhout: Brepols, 1999.