Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

CIDADES, Comunidades e Territórios

versão On-line ISSN 2182-3030

CIDADES no.26 Lisboa jun. 2013

https://doi.org/10.7749/citiescommunities.jun2013.026.art03

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Urban design, public space and creative milieus: an international comparative approach to informal dynamics in cultural districts*

Design urbano, espaço público e creative milieus: uma abordagem comparativa internacional às dinâmicas informais nos bairros creativos

[I]DINÂMIA’CET-IUL, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Portugal. email: pedro.costa@iscte.pt

[II]DINÂMIA’CET-IUL, Institudo Universitário de Lisboa, Portugal. email: ricardovenanciolopes@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

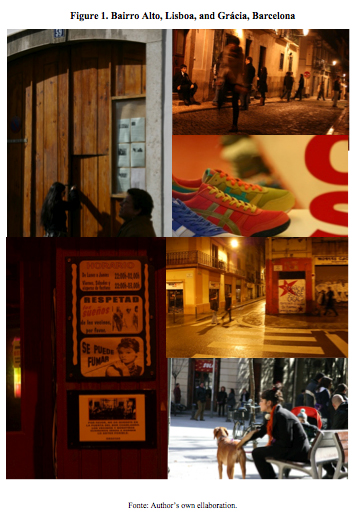

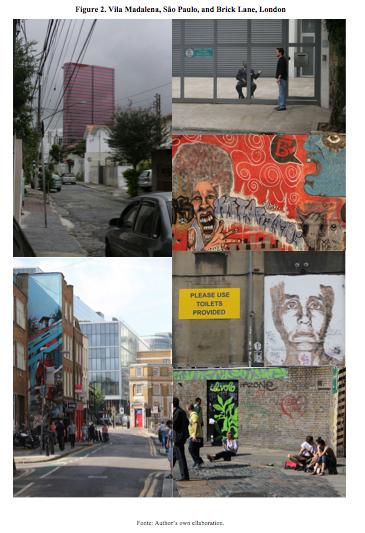

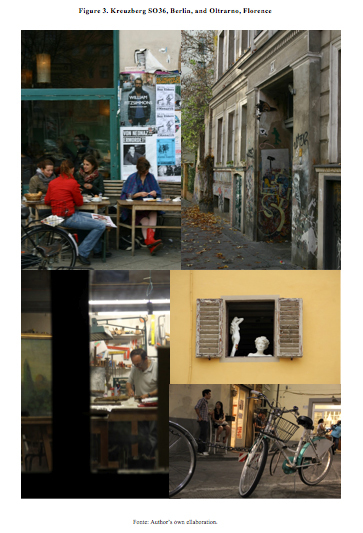

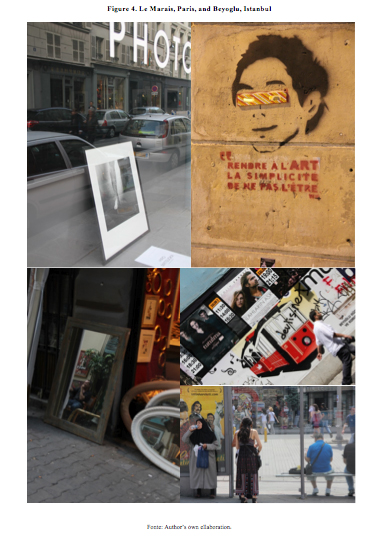

This paper explores the relation between urban design, public space appropriation and the informal dynamics taking place on creative milieus, from an international comparative perspective. Based on an empirical approach to urban morphology, everyday life and symbolic public space appropriation on those areas, ten cultural quarters around the world are studied: Bairro Alto (Lisbon); La Gracia (Barcelona); Vila Madalena (São Paulo); Beyoglu (Istanbul); Marais (Paris); Oltrarno (Florence); Akihabara (Tokyo); Kreuzberg SO36 (Berlin); Capitol Hill (Seattle); and Brick Lane (London). They represent very diverse situations in terms of their historical, cultural and economic backgrounds as well as in what concerns the spatial conditions that support creative clusters and the vitality and sustainability of “creative milieus”. Drawing on literature review and on the recollection and critical interpretation of visual information on these areas, a comparative approach to these cases is developed, considering multiple analytical dimensions, which enable us to map and characterize the diversity of urban cultural districts. This may provide a contribution towards the development of a new planning agenda for dealing with urban creative dynamics and cultural quarters.

Keywords: Creative milieus; Urban design; Cultural quarters; Public spaces; Informality.

RESUMO

Este artigo explora a relação entre o design urbano, a apropriação do espaço público e as dinâmicas informais que têm lugar nos meios criativos, a partir de uma perspectiva comparativa internacionais. Com base numa abordagem empírica à morfologia urbana, analisamos a vida quotidiana e a apropriação do espaço público simbólico nessas áreas, em dez bairros criativos à volta do mundo: Bairro Alto (Lisboa); La Gracia (Barcelona); Vila Madalena (São Paulo); Beyoglu (Istambul); Marais (Paris); Oltrano (Florença); Akihabara (Tóquio); Kreuzberg SO36 (Berlim); Capitol Hill (Seattle); e Brick Lane (Londres). Estes bairros representam situações muito diversas em termos de antecedentes históricos, culturais e económicos, bem como no que se refere às condições espaciais que suportam os clusters creativos, bem como a vitalidade e a sustentabilidade dos "meios criativos". A partir da revisão da literatura e da refexão e interpretação crítica da informação visual destas áreas, desenvolve-se uma abordagem comparativa destas áreas, considerando múltiplas dimensões de análise, quer permitem mapear e caracterizar a diversidade dos bairros culturais urbanos. Tal pode trazer um contributo para o desenvolvimento de uma nova agenda de planeamento para lidar com as dinâmicas de creatividade urbana e dos bairros culturais.

Palavras-chave: Meios criativos; Design urbano; Bairros culturais; Espaços públicos; Informalidade.

1. Introduction

Cultural quarters have been widely studied in recent years as they embody broader structural transformations associated with urban change (Bell and Jayne, 2004; Cooke and Lazzeretti, 2008). Wide social, economic, political, spatial and cultural forces shaped a variety of urban districts, quarters or villages, which are present in cities across the world. However, while this same kind of gentrified residential city enclaves, gay villages, ethnic quarters, ghettos, red light districts and creative and cultural quarters can be seen as a commonplace feature of contemporary urban landscape, there are significant differences among them which need to be disentangled (Bell and Jayne, 2004). The diversity and complexity of these territorial systems is often recognized as the ground to their resilience, and to the capacity to develop specific governance mechanisms and symbolic attributes which enable their long term vitality.

The “creative milieu” concept is a powerful resource to analyse this variety of situations (Camagni et al., 2004). It enables us to examine each situation as a combination of three intertwined layers (a localized production-consumption system; a governance system; and a symbolic system), fundamental to understand the specific conditions and ambiances which seem to be determinant to embed sustainable creative processes in these areas, and relating them to urban socioeconomic and morphological dimensions. The relation between these creative dynamics and planning has often been neglected. However, the re-thinking of the city through micro-scale systems of action instead of large projects is essential nowadays. The relevance of understanding everyday life and more informal and ephemeral initiatives for cities’ planning is fundamental, requiring the refocusing of our attention and the use of new methodologies.

In this perspective, this paper aims to discuss this relation between urban design, public space appropriation and the informal dynamics taking place on these creative milieus, from an international comparative perspective. Based on an empirical-oriented approach to urban morphology, everyday life and symbolic public space appropriation in those areas, ten cultural quarters around the world are studied: Bairro Alto (Lisbon); La Gracia (Barcelona); Vila Madalena (São Paulo); Beyoglu (Istanbul); Marais (Paris); Oltrarno (Florence); Akihabara (Tokyo), Kreuzberg SO36 (Berlin), Capitol Hill (Seattle) and Brick Lane (London). They represent very diverse situations in terms of their historical, cultural and economic backgrounds as well as in what concerns the spatial conditions that support creative clusters and the vitality and sustainability of “creative milieus”. Drawing on literature review and on the recollection and critical interpretation of visual information on these areas, we aim to provide better understanding of the key factors behind the development of these areas, in order to assist a new planning agenda for dealing with urban creative dynamics and cultural quarters.

After this introduction, the next section will offer the framework for the pursued analysis, relating the creative milieus development with their morphological, symbolic and informality conditions. In section 3, a brief panorama of the 10 cases is provided, with a short description of their main features and their urban insertion. A comparative perspective of the 10 cases, through a set of analytical dimensions, is developed on section 4, aiming to systematize and map out relevant factors for the development of urban creative districts. Finally, a concluding note provides some perspectives towards policy orientations for dealing with urban creative dynamics and cultural quarters.

2. Cultural quarters and the “creative milieu”: informal dynamics as drivers for artistic vitality

In recent years multiple territories have stood out as ‘creative milieus’ as they offer a specific atmosphere or certain conditions required to embed and develop sustainable creative processes in cultural activities (see Camagni et al., 2004; Cooke and Lazzeretti, 2007; Costa, 2007; Costa et al., 2011; or in a wider perspective, O’Connor and Wynne, 1996; Scott, 2000). This label usually congregates very diverse situations, which are generally based on specific governance mechanisms that play a key part in most of those success cases. Our study in this paper focuses a specific kind of these “creative milieus”, the “cultural districts” or “cultural quarters” (Costa et al., 2008).

These cultural quarters, in their diversity, have been broadly studied as they embody wider structural transformations associated with urban change (Bell and Jayne, 2004; Cooke and Lazzeretti, 2008; Porter and Shaw, 2009). It is not our aim to describe or discuss here their huge diversity, concerning both their origins and their main characteristics (more central or peripheral, more or less gentrified, more inclusive or segmented, more diverse or coherent, etc. – see Bell and Jayne, 2004 on this). In effect, the diversity and complexity of these territorial systems is often recognized as the ground to their resilience, and to the capacity to develop specific governance mechanisms and symbolic attributes which enable their long term vitality.Acknowledging the importance of “classic” factors (such as dimension, density and diversity of social practices – many times translated into expressions such as agglomeration, scale, interaction, networking, tolerance or others) to this, but also the crucial role of the symbolic sphere potentiated in cultural activities (Costa et al., 2011), our aim in this paper is just to discuss how the characteristics and the informal dynamics occurring in these places contribute to their vitality, relating those to their specific morphological and spatial conditions. In effect, the diversity and density of activities and the urban design and morphological conditions clearly influence these areas’ creative dynamics – as suggested by Hospers (2003), Gehl (2004) or Balula (2010), and witnessed by Costa and Lopes (2012) in some of these quarters. Urban material conditions, as the way they are appropriated and perceived by people, are naturally a key factor in the vitality and in the long term conditions for the sustainability of these spaces. Besides, the common diversity of rhythms and daily habits of its users, make us aware of their multiple layers of uses and symbolic codification.

As Costa and Lopes refer, in these spaces the symbolical sphere plays an important role and is fundamental to understanding both their vitality and their fragmentation (Costa and Lopes, 2012), particularly if they are central nodes in the conviviality and sociability mechanisms that are vital for reputation building and gatekeeping mechanisms on cultural activities (Costa, 2012). People who come to these spaces identify and many times deliberately look for a created image (of the place, of themselves, of their groups, of what they want to be), that is, for the symbolic meaning of that place. These are particular places for representation, for the assumption of specific lifestyles and ways of life (O’Connor and Wynne, 1996) and therefore, the concept of urban theatricality is sharp in these territories. Consequently, along with liminality processes, we can watch a natural segregation of practices and people in the different spaces (or even in the same places, each with several codified layers of representations, differently de-codified by their different audiences and users). Often, this process is based on auto-segregation, but sometimes it also involves conflict between the diverse potential users and power relations that take place within that system or in the framework of its external regulation (Costa and Lopes, 2012).

The “creative milieu” concept, in line with the GREMI approach (Camagni et al., 2004), is the theoretical backbone for analysing this variety of situations. Each one can be seen as a combination of three intertwined layers: a locally embedded production-consumption system, rooted in the territorial characteristics; a governance system, mixing the formal and informal endogenous and exogenous-based regulatory mechanisms in a specific way; and a symbolic system, involving both the external image(s) and the self-representations of the area. This triple perspective is fundamental to understanding the specific conditions and ambiances that seem to be determinant to embed sustainable creative processes in these areas, as well as to relate them to urban socioeconomic and morphological dimensions. Having this broad framework in mind, our specific aim in this text is to understand how informal dynamics can be seen as drivers for artistic vitality, in a wide range of “creative quarters” situations. Re-thinking the city through micro-scale systems of action, instead of just large projects and flagship interventions is essential for planning the city integrating urban creativity and real creative dynamics. Understanding everyday life and the role of more informal and ephemeral initiatives for cities’ planning is fundamental, requiring (re)focusing our attention to this specific issue and the use of new methodologies. That is what is developed in the next sections, first framing our approach to each case study and then drawing some comparative elements which enable us to typify the main features that seem essential to understand the role of this informality to these areas’ vitality.

3. A brief overview of ten cultural quarters: urban morphology, creative dynamics and informality

As explained before, our main purpose is to discuss the relation between urban design, public space appropriation and the informal dynamics going on around the creative milieus from an international comparative perspective. Ten cultural quarters around the world are used to illustrate our discussion in this paper, and will be briefly presented in this section. They represent very diverse situations concerning their historical, cultural and economic backgrounds, and embody quite distinct spatial and morphological conditions. However, we acknowledge all this variety in the support of creative clusters and in the vitality and sustainability of these “creative milieus”.

Our methodological approach to these areas in this work was not the most conventional. In effect, some of the areas have been previously object of in-depth analysis in broad research projects (Costa et al., 2010, Costa and Lopes, 2012; Costa, 2008, 2012, 2013a; Lopes, 2012). Others, on the contrary, were approached now for the first time. Our option was to use a combination of more traditional methods (particularly bibliographic survey on all the cases, and use of interviews and other information for the cases where available), with a more unconventional ethnographic-based approach to each quarter, essentially based on image recollection and participant observation. This approach, centred essentially on the observation of urban morphology, everyday life and symbolic public space appropriations, allowed us to study these territories from a nearest perspective, which, although more contaminated by subjectivity, seemed essential for us to compare these ten areas, around the world, trying to reach their effective diversity, naturally embedded in cultural, socioeconomic, political and material specificities. If we are studying informal interventions we need to go down to the ground to “see”, to “feel” and to “smell” what is happening, reaching dimensions which are many times discarded by researchers or city planners who work at their ateliers without that specific knowledge of the field. While accepting the fragilities and limitations of this kind of approach, we propose to test with our work this kind of methodological tools in order to get empirical information which allows us to enrich the discussion on the informality mechanisms and their impact in the creative dynamics of these areas.

We intended to shed a light on aspects such as urban morphology and everyday life in each neighborhood, and to understand their relation with the specific symbolic system, thinking each case in the framework of its’ cultural, socioeconomic and governance particularities, and understanding how informal and formal mechanisms contribute to the development and vitality of the creative dynamics of those areas, in generic terms.

Bairro Alto was the first urban core built outside the city walls of Lisbon (Portugal), dating from the early sixteenth century, located near one of the city gates of the period. Its design is adapted to the topography, adopting an orthogonal grid. The quarter is characterized by its narrow streets composed mainly by buildings of Pombalino period, and despite the numerous renovations and additions, it keeps essentially its historical and picturesque image. The sidewalks are narrow or nonexistent. The traffic is closed inside part of the quarter (in recent decades), giving access exclusively to residents and loadings. So, main car traffic is carried by the peripheral limits of the quarter, being possible to cross it by Rua da Rosa that divides the quarter into two parts with different characteristics, with a mostly residential Western zone, and an Eastern zone which is characterized by functional diversity, where the majority of functions with social character occur. Public space represents a small area of the quarter, mostly in the streets that cross it, and its peripheral limits (with rare green spaces or urban furniture for permanence). Thus, the streets assume the function of “living room of the quarter” to the regulars who wander and chat there during daytime and for those who flock at the quarter at night, standing or sitting along the streets. Considered marginal, insalubrious, and poor in habitability conditions in the mid-twentieth century, it led to projects for demolition of the quarter. However this did not occur, which allowed the deployment in this area of the city of a series of activities that took advantage of the fact that it was a central and relatively low-priced economic zone to develop, such as the case of the printing cluster. It is following this logic that the contemporary creative industries begin to develop in the territory, articulating the axis Chiado – Bairro Alto, and exploring the long-term interrelation and complementarity between the institutional-daily pattern of Chiado (the portion “within” the ancient walls and an institutional cultural pole of the city) and the alternative-marginal-nightlife image of the Bairro Alto area (Costa, 2007, 2009). This fruitful relation, exploring the transgressive tradition in terms of sociability and conviviality in Bairro Alto, fed the area’s development as the main cultural area of Lisbon. The artistic universities placed in Bairro Alto as well as in Chiado increased the critical masses of those who lived and attended the activities in this district, and it was in this general context that this part of the city affirmed itself over the years as the cultural and creative place for most cultural activities in the metropolitan area, although in recent years, this centrality has shifted progressively for consumption-oriented and social and conviviality-based activities, also essential for the structuring of the creative activities cluster, though not centered on cultural creation and production (Costa, 2012). Facing gentrification risks and huge use conflicts the area’s sustainability is challenged by several sides (Costa et Lopes, 2012; Costa, 2013), but informality, openness and tolerance to diversity and liminality are key-elements in a place which still is associated with a marginal, bohemian and alternative way of life, despite its growing massification and symbolic mainstreaming.

Gràcia was also the result of an urban development outside the city of Barcelona (Spain). Distancing approximately two kilometers from the walled city it developed as an autonomous “pueblo and these structural characteristics remain until today, which is also reflected in a strong sense of local identity in its population. It was incorporated in the city of Barcelona after Cerdà[3]plans, in the nineteenth century. The narrow streets are usually framed by 4 to 5-story buildings. The orthogonal grid is interrupted several times by squares, where people meet, which are the main public spaces of the quarter, equipped with plenty of urban furniture and shaded from the sun by trees. These are the scenarios for public convergence of people with a high degree of heterogeneity. Gràcia is still characterized as an autonomous “small city” within Barcelona. It is perfectly possible to live, to work and to access cultural events without leaving the quarter. This mix of “needed activities”, but also the ones of “social” and “optional” nature (Balula, 2010: 50) grants vitality and dynamism to the quarter throughout the day, being one of the cases which presents a better balance between the three groups. Circulation in the quarter is correctly hierarchized and some streets are closed to traffic, while others only allow circulation of specific vehicles and bicycles. The parking congestion issue is not as accute as in other cases (e.g. in Bairro Alto and Vila Madalena users can take hours to park their vehicles). Sidewalks are regular and it is usual to find the sidewalk at the road’s plan to solve the problem of the narrow streets; with this solution and the traffic controlled, most of the streets are large sidewalks most of the time. The quarter doesn’t have significant topographical variations in spite of presenting a slight slope throughout the whole territory.

In Gràcia creative activities are further integrated with local dynamics, being one of the case studies which expresses a better relation between all activities. Although it is a neighbourhood where crowds flow, mixing the more traditional and the alternative, these seem to live well among the quarter dynamics. Gràcia shows a huge vitality along the day, joining traditional middle class residents, intellectuals, immigrants, Erasmus students and other sorts of gentrifiers, in what can be considered a quite balanced quarter, where local authorities and associative movements have a large preponderance in its governance mechanisms. In spite of all this, creative dynamics in recent years have been turning to a more institutionalized and less informal pattern losing in some circumstances some spontaneity and quality, into a more entertainment based pattern.

Vila Madalena, in São Paulo, Brazil, started as a small group of houses in the outskirts of São Paulo. Only in the early twentieth century, with the construction of the railway line that would connect this small cluster of blue-collar workers’ houses to the city center, and then definitively in the 1970’s, with the location of the Arts University of São Paulo in a close neighborhood, this area starts to assume the setting that we can find today. Like São Paulo itself, it is characterized for being in constant mutation. From the beginning it was a quarter composed mostly by single-family housing. Today, it is in quite advanced state of gentrification and many of the single-family buildings that composed (and symbolized) the quarter have been replaced by buildings with more than ten floors. These urban changes are disfiguring, in physical terms, the “old” artistic quarter. But this was itself a result of the post 1970’s gentrification of the precedent blue-collar workers neighborhood, although then the change was not very much reflected in the buildings characteristics. Fast urban change, associated with economic and demographic expansion, progressively got to new areas of the city. The municipal master plan allows the replacement of the old buildings by others with completely different characteristics (contrary to what happens in French, Portuguese, Italian or Spanish cases, where regulations don´t sanction great modifications in the characteristics of existing edification[4]). These kinds of alterations in edification typologies of Vila Madalena are changing the intrinsic characteristics of the district, due to the changes in uses and in population that these restructurings generate. Old buildings are mostly replaced by private condominiums that not only involve lesser levels of public space appropriation but also do not guarantee the same mix of activities that was present in the old structure of the quarter. That has being driving a certain lost of vitality, contrary to what seems to happen in other districts, where the strategy has been maintaing mixed uses in the buildings and multifunctional areas, regardless of the use conflicts that this can generate.

In Vila Madalena, pedestrians’ circulation seems to be one of the most problematic aspects. The quarter is implanted in topography of pronounced slopes; sidewalks configuration, as in most of this city, is built by each landowner at their own will, which reduces mobility. In spite of this, sidewalks are large, and they are appropriated by costumers who come to the zone and other users. Formal and informal appropriation of these spaces is quite usual. Differently to what happens in other cases, the hierarchy of streets is less marked; cars can circulate in all of them, contrary to what happens in most of the other cases, where access is easier or facilitated on foot or by public transport. After all, the car is really an important part of living (or using) this quarter, and its implications (mostly, congestion and traffic issues), are important downsides to the capacity to live and go to this quarter.Vila Madalena is in an advanced state of gentrification and will probably disappear as a “creative quarter” in some years, due to the challenges of gentrification and urban transformation. However, contrary to most European cases, like in many other cities with dimension and soft planning regulations (e.g. many American cities) this does not mean that the creative dynamics going on here could not move to other parts of the city, starting a new process of appropriation and “gentrification”.

Brick Lane area, in London, England, is an old industrial quarter, now associated essentially with immigrants from Bangladesh and new gentrifiers. In recent years it has affirmed itself as one of the most creative places of the city, where generations, styles and habits coexist side by side. The East End zone at London has been for many years characterized by migratory fluxes of people of a large heterogeneity such as Irish, Jews or Bengalis. The zone of Brick Lane [5], within this area, is an obvious reflex of this knowledge sedimentation which marks this multiethnic part of London. The fluxes of immigration are an integral part of this city’s history, contributing to its dynamic and vitality: “Waves of immigrants have passed through, (…). They brought with them trades, skills crafts and talents that have helped underpin London’s position as a world city” (Landry, 2000: 111). Although original immigration in Brick Lane was essentially connected to the industry located on the area, nowadays this place stands out, alongside Shoredich and Hoxton (North limits of East End), as one of the most “creative” of London area, being stages for fluxes of immigrants and other people who come looking for an alternative and informal way of life. From early 1990’s it started attracting numerous “creative people”, from around the world, offering a place where one could easily network with local artists, exchange knowledge, and be inserted in a milieu which could potentiate artistic life, providing evolution opportunities and mediation mechanisms (as in other cases, like Kreuzberg, also worldwide, at least for some specific art worlds).

However these more “informal, marginal and alternative” milieus that “help” the development of this kind of dynamics and attracted these people aren’t new in this part of the city. East End was along the history of London the place for the activities which were not welcome inside the city walls (like in Bairro Alto case), being one of the poorest places in London until the nineteenth century. So industry, lower classes and marginal life, often connected to criminality and bohemia, dominated this part of the city until the 1990’s, when creative clusters began to take the place of the abandoned industries. This area has been vastly transformed during the last decades, not due to an intentional and careful planning strategy, but essentially due to its’ own dynamics, combining specific governance, socioeconomic and cultural factors, all this regardless of a set of key programmes that enhanced some dynamics around projects such as Rich Mix, the Stipafields Market, the Truman Brewery or Whitechapel Gallery/ Library’s reformulation.

The informality found in this territory allows a series of dynamics that are impossible to find in other parts of the city, where people are not so tolerant and informality is less extended. Brick Lane mobilizes a symbolic capital which attracts artists and creators from around the world to come, intervene and live in this area. At the same time, visitors and consumers are also naturally attracted. This is one of the case studies (parallel with Kreuzberg SO36) where more appropriation by artistic ephemeral activities in the public sphere occurs, being a tolerant zone, where we can be easily surprised by new happenings, unlike other parts of London that don’t have this freedom of action. Street art is visible along the streets; works with quality and reputation contribute to fill with colours the traditional brick walls which were the image of the quarter. Many exhibitions take place on the streets, changing the image of the building space and contributing to a constant (re)discovery of public space, that appears to be less segmented in this part of London, segregated and dominated by power relations. Concerts on the streets, film sessions on rooftops of cultural clubs, ethnic food markets, clothes markets and “alternative” products are some of dynamics which contribute to the vitality of the place which seems to be the one less gentrified from our universe of case studies (this quarter maintains largely its original population contrary to what happens in Shoreditch and Hoxton, for instance).

In terms of morphology the area is level and composed by buildings with different heights, drawing a jagged skyline (like in Gràcia). Likewise most of the other case studies, use conflicts are very significant, resulting from the diversity of publics, lifestyles and expectations of those who live and come to this place. This level of conflict has probably been contributing to keep this dynamics less institutionalized, and the fact that there are other creative quarters in London has certainly also contributed to hold back the gentrification process.

Kreuzberg SO36, located in the West part of Berlin, Germany, near the river Spree, is one of Berlin's cultural centres, in the middle of the now reunified city, evolving from its recent history as one of the poorest quarters in Berlin (in the late 1970s and 80’s, during which it was an isolated section of West Berlin), mostly dwelled by subcultures, to one of the most vibrant centres in many art worlds in the European context. Kreuzberg consists of two distinctive parts (SO36 and SW61, standing for the old postal codes for the two areas in West Berlin). Kreuzberg SO36, home of many immigrants (and second-generation immigrants, notably of Turkish descent) and the main contemporary nest for creative dynamics, is marked by diversity, multiculturalism and informality, attracting creative people from around the world and achieving a unique symbolic status. At the same time, the district is also characterized by high levels of unemployment and some of the lowest average incomes in Berlin.

Along history, this quarter (as Berlin itself) has staged many morphologic, political, cultural and social alterations, which have contributed with its ups and downs to the construction of the image of the city. This neighbourhood started developing in late nineteenth century, resulting from the fast industrial expansion after the foundation of German Empire in 1871, which continued until the end of the First World War. Based on expansive housing development, related to industrial growth, quickly it raised from an almost rural territory to the area with highest population density in Berlin. But it was the end of Second World War that changed its image definitely, as large parts of the city were in ruin and Kreuzberg SO36 was not an exception (being one of the industrial areas particularly focused by bombing). It was in this historical context, along with the post-war city division, that the traditional dwellers left the poor zone of Kreuzberg SO36 and moved to newer parts of the city. This social change was essential to start the development of “alternative” dynamics in the quarter. The numerous abandoned spaces, such as residences, old workplaces, shops and industrial zones, were occupied by new dwellers of lower classes that came to live in the quarter. The huge heterogeneity of experiences brought by new inhabitants was essential for the development of the creative dynamics. “The Kreuzberg mix (Rada, 1997) refers not only to an ethnic and social mixture but also to a population with a partly alternative attitude and rebellious character, a strong subcultural influence and simultaneity of living, small-scale crafts and shops in the same buildings” (Bader and Bialluch, 2009: 94).

In spite of its central location in the city, it was isolated during the “Berlin Wall” period, which closed the quarter near to River Spree, not allowing contacts with the Eastern part of the city. Even within the West side of Berlin, the area lost its centrality, enclosed by the Berlin Wall on three sides, and was quite unattractive for real estate investments. Particularly since the late 1960s, increasing numbers of immigrants, students and artists, attracted by cheaper land, began moving to Kreuzberg, which became notable for its alternative lifestyle and its squatters. Berlin’s punk rock scene or LGBT life, for instance, had its epicenter here. With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the quarter earned a new centrality, founding itself on the heart of the city again, and the streets that used to finish in blind alleys earned new life. It was in this period that the place stood out as the “creative quarter” in international circuits, according to Florida (2002). The initially cheap rents and high grade of XIX century housing made some parts of the borough more attractive as a residential area for a much wider (and richer) variety of people. Today, Kreuzberg has one of the youngest populations of all European city boroughs.

In terms of morphology the quarter is located on level ground and is composed by large sidewalks and streets. Most buildings’ height don’t’t exceed the street width, which contributes to a good relation between edification and people. The mixed-uses of buildings contribute to the diversity of activities along the streets. Public sphere, more than strict public space, reveals its’ real importance here, because most of the year the climate conditions are not very encouraging on the streets, the principal stage of interaction in other case studies. Other formal or informal convivial places emerge, in the public sphere, many of them of a transitional or ephemeral nature.

Kreuzberg SO36 is clearly an example of how ephemeral artistic interventions and creative appropriations can generate and enhance creative dynamics in a zone of a city, contributing to the redevelopment of “expectant spaces” believing this kind of dynamics helps reinventing the cities. Berlin is a laboratory for this kind of experiences, sometimes even promoted by official planning policies. Empty spaces, residential buildings, bunkers, old industrial spaces have been reconverted through the change of uses of these out-of-function spaces and their reintroduction in the everyday life of the quarter, creating new cultural places, leisure spots or residences. “Like in a surrealism collage, elements of opposite worlds meet” (Oswalt, 2010: 2), appearing and disappearing with at high speed, contributing to reconvert innumerous spaces of the quarter. Actually, the huge associative dynamic of its tolerant and heterogeneous population, enhances a quite decentralized cultural supply, which along its multicultural nature, helps to maintain the gentrification of the quarter under control.

Oltrarno is a “traditional” quarter on the South bank of River Arno, which always has been connected to the art world, like the city of Florence itself. However, although over the last centuries it has been at the forefront of new ideas, nowadays it essentially lives on an image constructed for the vast touristic demand that arrives every day to see the city of renaissance. So, its symbolical capital is mostly associated to heritage (unlike what we found in Brick Lane or Kreuzberg, typically connected with more alternative and informal contemporary art worlds). In spite of it, the city continues to be one of the most important centers of fashion in the world and maintains many traditional artisan shops and handicrafts along the streets. Over the last centuries Oltrarno has been occupied by a mix of inhabitants, piecing together in same place palaces and modest residences. This mix of population is maintained until today, despite its central location in the city of Florence. Oltrarno is not an exception to our quarters and is also clearly gentrified. Although, it has its particularities, and is acknowledged as one of the most interesting and lively parts of the city center inside the old walls. Tourists are less present than on the other side of the river and it offers a good residential milieu and a broad mix of central functions and activities (necessary, social and optional).

The quarter is composed by narrow streets and typical buildings of medieval period that haven’t changed a lot over the last centuries, what enhances a tradition-related image (like in the Bairro Alto case). Motor vehicle traffic is not a problem when a large part of population prefers to cycle. In Oltrarno trendy cafés for young creative’s mix with old activities, bohemian life and conviviality mix with traditional usages. The use conflicts are not as visible as in other cases, while the quarter seems to connect and equilibrate all its activities; this seems to be a constant in more gentrified case studies, where uses tend to be more balanced and less informal. Nevertheless, the liminal character of the quarter, which is so important to the creative world, seems less visible and the space for production is reduced.

In effect, of all studied cases, this is the one where creative activities are less informal; some have been the same over centuries and even more contemporary ones often happen without huge spontaneity. In this sense it is a case different from all others. Like many, it has turned to a more consumption-oriented and symbolic-based territorial system. However, if in other cases, like Bairro Alto for example, some informality conquers the streets during the day, in Oltrarno tourists are essentially those who occupy this stage in everyday life. The main focus of attraction is city’s heritage, more than creative informal or alternative dynamics. The symbolic-system is not so connected to artists’ recognition or to specific contemporary art worlds like in other cases, but is essentially linked to the glorious past of the city, and its touristic-related cultural activities.

Beyoglu is a vibrant historical district situated in Istanbul, Turkey, on the northern bank of the Golden Horn, which separates it from the old Constantinopolitan center. Beyoglu has been characterized in last centuries as the most cosmopolitan area of the city, particularly since the Ottoman period. It was always home for the foreign that arrived to the city from different countries, cultures and ethnic proveniences. With fairly uncertain limits, this area developed from the ancient Galata area (this side of the Golden Horn settled as a suburb of Byzantium since the fifth century), later better known as Pera (from the Venetian and Genovese merchant-based periods). During the nineteenth century, with this area’s Ottoman golden era, it was again home to many European traders, and housed many embassies, being the center of a westernized Istanbul, sanctioning influxes of modern technology, fashion, and arts.

Although being then one of the most “famous” and vibrant areas of Istanbul, a place for theatres, cinemas and international schools, populated by the most prestigious families of Ottoman Empire, in the middle of the twentieth century it went into decline, with a lot of empty spaces and without function (Durmaz, 2012). This situation, corresponding to the development of Turkish Republic, was mostly driven by the withdrawal of traditional residents moving to new developing suburbs (somehow akin to the Kreuzberg case). It was this economic and social change that allowed the return of the quarter to the map of the creative world in 1990’s. The situation brings up the development of new informal and alternative trends. New residents arrived at the empty spaces with cheap rents and brought with them new ways of life, trades and skills that mixed with the old origins of Beyoglu forming the vibrant milieu that we find in this area these days.

Istiklal Caddesi is the main street of Beyoglu, around which are structured most of the functions of the quarter. It is the center for the commercial and more “institutional” cultural functions, as well as most conviviality-related spots. The theatre, cinema, patisserie and café culture that still remains strong in Beyo?lu dates from the late Ottoman period, when this street was the center of modern Istanbul. But it is turning to the small neighborhoods, along the hill, with its narrow streets, that we start to discover the diversity of creative places and artist interventions that challenge the limits of the public space, where we can find cafes and informal clubs in old residencies or art galleries in improbable places. Beyoglu is now a mix of social strata, an ethnic and religious melting pot, with the most diverse lifestyles, backgrounds and classes. It has the capacity today of mixing and linking a diversity of functions, from one of the touristic centers of the city (not the main but effectively important), to a fundamental administrative and bureaucratic area; from one of the central shopping areas of Istanbul to a centre for most cultural functions. It concentrates a diversity of cultural and creative different clusters (audiovisual, music, architecture and design, performing and visual arts, antiques, ... – like other cases, such as Bairro Alto), in an area marked by its mixed uses, by bohemia and conviviality, with a capacity to polarize a huge metropolitan area like Istanbul, in several central functions. Its morphology and architecture, settled in multiple layers of its rich history, provides a very efficient ambience and particular conditions to the development of this milieu, and to the occurrence of more informal dynamics, which are central in contemporary life and vitality of this creative quarter.

Le Marais is a historic district in the centre of Paris, France, which is characterized by its distinguished ambience and the concentration of a multiplicity of creative activities and conviviality spots. Spreading across the 3rd and 4th arrondissements, at the North bank of the Seine River, it has a central location in the city, which is maintained since the thirteenth century. For long the aristocratic district of Paris, and hosting many outstanding buildings of historic and architectural interest, this area is nowadays marked by the image of a fashionable district, home of many trendy restaurants and cafés, fashion houses, creative ateliers, shops and hype galleries.

The area is characterized by its huge centrality, an essential feature for its vitality. In the very center of the city, near the main transport interface, and important shopping and touristic spots (reinforced in cultural terms by the proximity of Pompidou Centre, in Beaubourg, at the district boundaries), the area can easily polarize huge hinterlands for its function, seizing the density, diversity and heterogeneity of the social practices enabled by that centrality in greater Paris and all Île de France. Besides, it is a quarter long marked by diversity and heterogeneity, where tolerance is tradition. It was for long the main “Jewish quarter”, particularly since the end of the nineteenth century and during the first half of the twentieth, with the exit of some nobility, becoming a popular and very active commercial area, and hosting one of Paris' main Jewish communities until the Second World War, particularly in the area around Rue des Rosiers. At the turn of the twentieth century, this area had been renewed and revitalized around Jewish culture and it is now well known by this community’s gastronomy, bookshops or events. At the same time the quarter is the center of the Parisian LGBT community. The neighborhood has experienced an increasing gay presence since the 1980s, evidenced by the existence of many gay cafés, clubs and shops, and by a strong presence of gay culture on public space. This presence is mostly concentrated in the southwestern portion of the Marais, partially coincident with the previous, which extends more easternly. The Marais is also known for the strong Chinese community it hosts, particularly in the northern part of the neighborhood (4ème arrondissement). They settled in the area after the First WW, with activity centered on wholesale, mostly jewelry and leather-related products. All this diversity, mixed with a strong touristic attractiveness and a robust, but selective, gentrification process made the area one of the most heterogeneous and open zones of Paris.

In parallel, the neighborhood is marked by the fundamental importance of its morphology and urban design, which is also fundamental in the structuring of social and cultural practices and in public space appropriation. On the one hand, its particular morphology (traditional and very diverse from the Haussmanian Paris), with its narrow streets, its specific and small dwelling typologies, strict urban regulations and traffic restrictions, make this part of town particularly appealing for specific kinds of population (like in the Bairro Alto case), with less conventional lifestyles and familial models, and many times more likely to conviviality and specific appropriations of public space. On the other hand, due to the huge efforts on renovation and urban rehabilitation (particularly after the 1960’s pioneer safeguard plan in Paris, designed for this quarter acknowledging its special cultural significance), led by public authorities during decades, this area essentially maintained its traditional characteristics, but has witnessed the substantial change of its image, towards a progressive symbolic recognition in enlarged communities.

An intense gentrification process occurred; indeed, among all cases we focused this is the one where the gentrification process has been led to is extreme, with very high land prices, and significant changes in lifestyles, visible reflexes both in residential terms, and in commercial and cultural activities. In this process, it is important to note the role of regulations and local policies (e.g., commerce schedules, Sunday traffic closure and fairs, events…), as well as the relevance of sociability nodes, which are essential to the liveliness of the quarter, for their diverse communities and art worlds (although, contrary to other cases, this city have very spread conviviality and sociability spots, very segmented, in the diverse art worlds). This results in permanent activity mixes, crossing more “institutional” patterns, the aestheticized and “alternative” businesses, and also spaces for informality at streets, despite the strong economic-led gentrification of the residential and shop markets. Unlike other cases, the area is also clearly focused on specific audiences and art worlds, reveling a strong segmentation of cultural and creative activities that is felt throughout the Paris metropolitan area, with the spreading of artistic activity and creativity by more diverse spaces and areas.

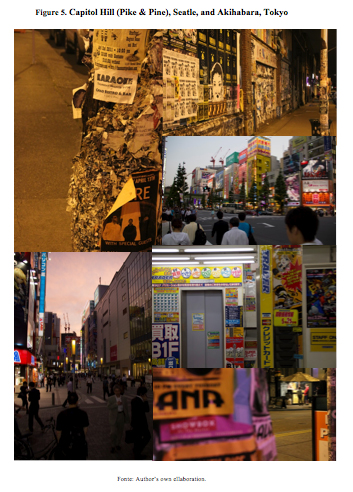

Capitol Hill (Pike & Pine) is a densely populated residential area in the centre of Seattle, USA. It is known as one of the city's most prominent nightlife and entertainment districts and the center of the city's gay and counterculture communities. It is marked by diversity and a concentration of activities (performing arts, nightlife, entertainment, small shops and ateliers, etc.), combining more institutional with more alternative ones. The area concentrates the city’s main movie theatres, its cinemathèque, and several performing arts venues, including a vibrant set of small performing arts theatres, dance studios and live music clubs. In parallel, nightlife and conviviality, as well as trendy shops and venues, perform an essential role in this creative territorial system.

Capitol Hill is situated on a steep hill just east of the city's central business district, and has been a bastion of arts and culture, with its rich and diverse history. In the broad area are located some of Seattle's wealthiest districts, and it anchors a lively shopping area, centred on Broadway, the commercial heart of the district. However, in a specific part of Capitol Hill, between Pine and Park streets, an unusual concentration of creative activities takes place. In effect, from all our case studies, this is the one that we can admit as the “cultural quarter” in the more strict sense, as its core can be much clearly defined by this concentration around a set of blocks between these two parallel streets (often known as Pike & Pine corridor or Pike & Pine triangle). The corridor is home to numerous bars, restaurants, and many unique independent retailers, symptomatically (self-)described as “one of Seattle's most vibrant neighborhoods (…) where city history mingles with an eclectic mix of hot new restaurants, seriously shoppable boutiques, eye-catching galleries, thoughtfully designed living spaces and more.”[6].

Besides this symbolic and effective link to nightlife, entertainment and performing, the neighborhood is also known by its linkage to gay life, particularly after large-scale gay residential settlement on Capitol Hill from early 1960s. The area has also a reputation as a bastion of musical culture in Seattle and was the neighborhood most closely associated with the grunge scene from the early 1990s, although most of the activity was actually located outside the neighborhood. It maintains today a lively music scene, but enlarged now to a variety of genres, both in terms of people and venues.

Outside the CBD, though affected by its expansionist dynamics, and embedded on the historical roots of Capitol Hill with its family buildings, many with significant architectural value, the area has a morphology that facilitated this appropriation and the development of this creative milieu (to a certain extent, with some parallel with the Vila Madalena case), despite the several (re)development projects that have marked the territory in recent years. Its broad streets with ample public spaces are easily appropriated by more formal or informal cultural activities and by sociability processes, day and night, which marks an effective difference with other areas of the city.

In effect, this area’s vitality contrasts with the Seattle Center area (which is a park, arts, and entertainment centre, developed after the 1962 International Exposition, featuring the “Space Needle”, Seattle's most recognizable landmark). Like in many other cities (including several of our case studies), this “planned” cultural/creative area (much more touristified and marked essentially by entertainment based day-life) does not have the capacity (neither the conditions) to embed a sustainable creative dynamic such as Capitol Hill area does. More organic dynamics, based on complex governance mechanisms, seem to have much more potential to develop and sustain creative ambiences than more institutionally-based and programmed actions.

Being one of the several cultural quarters in Tokyo, Akihabara is known as a major shopping area for electronic, computer, anime, games and “otaku” goods, clearly centered on popular culture. The quarter is dominated by the universe of manga/anime and by electronic and computer culture (both new and used items), which undoubtedly mark its landscape and its symbolic centrality in the city. Although there are many other areas in the city dedicated to the provision of these central functions, here they reach a multiplied dimension, taking to the extreme the crucial basic factors usually related to creative clustering (dimension/ density/ heterogeneity). In a metropolitan area with Tokyo’s dimension and complexity, the achievement of critical thresholds, even in specific market segments, makes all the difference, and this is further reinforced by a strong symbolic affirmation of the area within these clusters. Benefiting also from other cultural-based specialized offer (in fields like music or bookshops) in surrounding districts and its relative centrality in the city, this area differentiated and affirmed itself in recent decades as the main polarizer of those central functions. This denotes the clear specialization of the cultural quarters of this city, more than in all other case studies, by types of activities, but also by lifestyles and by their symbolic attributes. Electronic and manga/ anime dominate Akihabara, while other cultural and creative branches, such as performing arts, conviviality-related activities, or youth subcultures and youth-fashion related activities are the core in others (e.g. Shinjuku, Harajuku, Shibuya).

The density of this tissue is also expressed in the morphology, with densely populated streets, high buildings and height-oriented expansion (also in the case of commercial and cultural activity, with many shops and activities far from the ground floor, usual in this city). This forces interaction between public and private space, in an enlarged public sphere, that is dominated not only by creation and production, but mostly by consuming-based practices, gatekeeping and reputation building mechanisms. As Nobuoka refers, arguing about the role of users and their relation to place in the development of innovative milieus, “Its long history as an electronic retail district and a more recent influx of firms and shops focused on popular culture has created a strong place brand that continues to mark Akihabara as the capital of Japanese cultural industries. It is a space where different consumers, specialist subcultures and firms and their products can interact. The area functions as a hub where ideas and values are exchanged, tested and promoted.” (Nobuoka, 2010)

It is interesting to go further back in history and understand that, like in many of our other cases, this is an area that was beyond the formal limits of the old city, being just out of Sujikai-gomon city gate (today Mansei bridge) which was one of the city gates of old Edo (Tokyo), being the gateway from inner-city to northern and northwestern Japan, and many dealers, craftsmen and relatively lower class samurai lived there. The expansion of the rail line, at the end of nineteenth century, and later, after WWII, the settlement of the electrical manufacturing school and the development of an electric shops cluster around it, were decisive for the path of the district, which is rooted in this diversity and openness, such as many other cases.

Finally, the creative dynamics on this quarter could not be understood without referring also the importance of fans’ culture (“Otaku”, in Japanese, expression mostly used on anime and manga fans, but not only), and their specificities, essential to understand the development of the main cultural industries in Japan. This cultural particularity is strongly felt in this neighborhood (the “Akihabara Geeks” are renowned), and this enables us to reinforce completely the importance of a huge diversity of gatekeeping mechanisms, and of an enlarged version of sociability practices (here much less centered on nightlife conviviality than in other cases, but rather on other informal set of relations also established on this neighborhood’s public sphere), in the territorial structuring of the creative dynamics felt in this quarter.

4. A comparative perspective: crucial factors towards the vitality and sustainability of urban cultural districts

The ten cultural quarters briefly presented represent very diverse situations in terms of their historical, cultural and economic backgrounds as well as in what concerns the spatial conditions that support creative clusters and the vitality and sustainability of “creative milieus”. They were analysed trying to understand the relations and the specific particularities comparing similar dynamics in different realities, in order to identify a set of crucial factors to their development and sustainability which can help improving knowledge for dealing with urban creative dynamics and cultural quarters in planning and policy-making perspectives.A set of 9 dimensions were defined and confronted in the 10 case studies, evidencing common features concerning the vitality and sustainability of these spaces (a schematic summary of these analyses can be found on tables 1a through 1c:

1) Dimension, Density, Heterogeneity;

2) Symbolic capital;

3) Physical / symbolic centrality in the city;

4) Morphology;

5) Conviviality and nightlife;

6) Art world’s reputation mechanisms;

7) Main use conflicts;

8) Informality/ public sphere appropriation;

9) Specific governance mechanisms.

In every case study, naturally, the “traditional” factors to justify agglomeration and urban way(s) of life (Costa et al, 2011) are fundamental to the development of creative dynamics: the dimension, density and heterogeneity of social practices existing in that place. The importance of achieving critical thresholds, both on the demand and supply side, the capacity of attracting and relating people with different know-how, ideas and lifestyles, the relevance of diversity, openness and tolerance, have been broadly and quite unanimously recognized by the literature on creative quarters. That is particularly important in activities characterized by flexible labour markets based on project-oriented work, like most of the creative ones (Scott, 2000), where the proximity to the art world “localized” milieu is fundamental for the provision of knowledge and reputation, for artists, producers, gatekeepers and cultural consumers. This condition is naturally present in all case studies, though with diverse intensities, considering the range of central functions provided (and their hinterlands), some cases more focused in specific art worlds, others more broadly.

The symbolic-capital is one of the most important features in the creative field, in an intertwined alchemy between the reputations of artists, artworks and places (see Costa, 2012 on this). Within this process, the image and the internal and external representations about the territorial system play a significant role in the development and in the sustainability of creative dynamics, being an essential layer of the “creative milieu”. It can be essential to enhance artistic practices, boost performativity, enable investment and entrepreneurship, promote public action or even to give space for liminality, on a diversity of fields related to cultural provision, consumption and creative expression. But on the contrary, it can also be an inhibiting factor for all these. Thus, the permanent negotiation of the image of the quarter, in multiple arenas, differently valued by its multiple agents is an essential aspect in the evolution of each of these territorial systems. That is particularly sensitive when we associate to this the reputation of artists and their work. Creative art worlds are intimately dependent on recognition and on symbolic sphere, and these quarters are often special arenas for this kind of affirmation and legitimization. The diversity of reputation building mechanisms (and frequently their natural conflicts, with cultural legitimization often associated to social and cultural distinction) makes this aspect particularly important in terms of system sustainability, as the many times the evolution of these quarters (e.g, with symbolic mainstreaming, associated to increase popularity of the area, or gentrification, as seen in several of our cases) can be very challenging for the permanence of most creative (or at least transgressor/ alternative) cultural actors in the neighbourhood.

The centrality in the city (be it physical or symbolic) is also a factor of fundamental importance. It is actually experienced in all case studies (e.g. importance of public transport accessibility in most of them) and was linked to their development, even when they were not exactly at the centre of the city. But the physical centrality (in some cases historical centers; in others, specific central quarters appropriated by their specific urban characteristics) is often complemented and even compensated by the symbolic centrality of those neighborhoods in the respective city. They are all acknowledged as cultural or creative areas, even if in some cases there are all other creative districts in their cities. Their centrality for some specific art worlds or their ample recognition as cultural spots or sociability nodes is crucial to the dynamics both at the demand and supply side. Gatekeepers have also a determinant role here, in this symbolic affirmation, although in this case, as demonstrated before (Costa, 2012, 2013), the proactive action for promotion of a specific place as “cultural” or “creative” can have more harmful effects than positive ones (via the deepening of gentrification processes and symbolic mainstreaming of the area, discouraging artistic permanence in the area).

The morphological characteristics of the districts condition the ways people use them. Depending on its design, the quarter’s characteristics condition public space and their appropriation. So, the historical epoch of its construction and its design plays an important role in the quarter’s milieu (be it by their charisma and ambience, be it by the selectivity of inhabitants and activities they cause – e.g Marais, Oltrarno and Bairro Alto cases). The typological characteristics of the buildings also condition the sustainability of the creative dynamics and alterations of these characteristics can speed up the gentrification process (e.g Vila Madalena). The private spaces belonging to the public sphere condition the way adjacent public space is appropriated. Alterations in typological characteristics cause changes in social composition of the quarters and on its uses. Often, these spaces congregate diverse users, with different lifestyles and appropriation forms, and it is this multiplicity of users what embeds liveliness along the day. Mixed function buildings, with commerce along the streets, contribute to the diversity of happenings enriching the experience of walking the streets, and providing a more experienced public space, as turns out to be true in all cases.

Conviviality and nightlife also perform a well-documented fundamental role in the development of creative dynamics in creative quarters, and this is no exception in our cases studies. In some of them the centre of conviviality is based on nightlife (more oriented to specific cultural field(s) or more generalist), but in others (eg. Akihabara) it is essentially based on other informal mechanisms for encounter and interaction. These moments are essential for diffusion of know-how and information, access to tacit knowledge, face to face contact, and mostly, to reputation building mechanisms, which are fundamental in creative activities, mostly the ones that are structured in project-oriented labour markets (that is, most sectors). These places represent an opportunity for all this to happen, which is one of their essential tasks as structuring pieces of these creative milieus. Despite all the use conflicts that this function often represents (particularly in the nightlife case with its externalities, experienced in most of our cases), this is a fundamental part of the overall functioning of these systems, essential to their development and to the vitality of the respective art worlds.

Linked with the previous, these places assume themselves as central in the reputation building mechanisms and in gatekeeping processes in many art worlds. In some cases they are central in specific art worlds (e.g., manga and anime in Akihabara; street art in Brick Lane); in other cases they are more transversal and provide coherent and extensive reputational and symbolic value to the gatekeeping mechanisms in multiple art worlds, both more alternative or more mainstream (e.g., Bairro Alto, Capitol Hill, Beyoglu). However, situations can be very diverse, concerning the linkage of these reputation building mechanisms and their influence in the specific art worlds. For instance, sometimes they are essentially local (e.g., Altrarno, for many art worlds), sometimes they have international scale (e.g. Kreuzberg). Sometimes they are understood just in specific cultural fields or subcultures; sometimes they are more universally shared (or even broadly massified or turistified). Public space appropriation (formal and informal) and all processes associated to conviviality and nightlife perform a significant role on these mechanisms, although very differently in the diverse case studies, as was mentioned before.

The different interests and motivations of the diverse agents in each of these territorial systems are naturally often contradictory. The main use conflicts among them are one of the critical aspects for the development and long term consistency of these creative milieus. In effect, as expressed before (e.g. Costa, 2008, Costa and Lopes, 2012), the conflicts of uses in each of these spaces (e.g. between users and residents, night users and day users, traditional residents and newcomers, traditional cultural and new activities), are a unceasing dimension of its life (and even one essential dimension to certain kinds of creative activity, by its intrinsic liminal and alternative nature). This conflict is expressed in different arenas (real estate market, public space appropriation, symbolic sphere, …) and is perceived diversely by the users and the multiple art world’s agents involved (e.g. graffiti or urban intervention). These conflicts are felt in all our case studies, particularly in two fields. On the one hand, through gentrification, and the different power relations in appropriation of public and private space; on the other hand, in numerous conflicts between the diverse individual or group interests, expressed in externalities (such as congestion of parking or traffic infrastructures, noise, urban cleanliness issues, etc.). Despite all their problems and consequences, some of these conflicts may have an important role in the sustainability of these systems as creative areas, as they can inhibit or postpone gentrification processes (e.g. most of these externalities are key factors in avoiding conventional gentrification processes in the Bairro Alto area, having a key role in the selective – more creative and specific lifestyles oriented – gentrification process (Costa and Lopes, 2012; Costa 2013a).

Another relevant factor is the informality and public sphere appropriation going on in these districts, where the possibility for interventions and artistic appropriations in the public sphere is more flexible. The informality and liminality that mark these territories is vital for its sustainability as part of their daily dynamics and contributing to a strong local identity (Costa and Lopes, 2012). In effect, on a scenery in which the boundaries between public and private sphere are constantly blurry, and where the ephemeral gains its space, new creative possibilities emerge. Mostly, in a more open, tolerant and un-institutionalized framework, new fields for developing and exploring new sorts of creative processes and informal-based dynamics materialize. So we witness throughout our case studies all these sorts of processes, although with diverse patterns: artistic appropriation of public sphere (e.g. graffiti and street art, in all of them, but also the aperture of private space to public and contamination strategies – e.g., Kreuzberg, Brick Lane, Beyoglu, Vila Madalena), informal appropriation by users (e.g, streets appropriation in Bairro Alto or Gracia), performativity in public space, many times associated to liminality processes or to expression of identities or of the self (multicultural or GLBT expression, e.g. Brick Lane, Marais, Capitol Hill). After all, this is particularly remarkable also because informal and ephemeral appropriation of public spaces in the city can have enough interest in a historical era that embraces time delays caused by economic interests (such as property speculation) or bureaucratic processes (such as licensing procedures) that can often lead to cities’ death. These informality-based behaviours are certainly a way to maintain (even if temporarily or ephemerally in some cases) the creative vitality and the liveliness of those spaces.

Finally, a crucial factor for the development and sustainability of the creative dynamics, in each case, is the way they relate with their specific governance mechanisms. The different case studies represent diverse logics of governance that are undoubtedly a key factor to the sustainability of those creative milieus. Some rely more on market functioning, others are more supported on public intervention, others are essentially embedded on a complex network of formal and informal interdependencies between their multiple agents, in the most diverse fields. Effectively, all of them are a mix of all these, and of all the interests and motivations of the stakeholders involved, at the economic, social, political, cultural or symbolical arenas. Some represent more “flexible” planning backgrounds, others more strict or straightforward actions, with implications on the long term sustainability of the systems as a culturally-led territory (e.g., more flexible planning rules, in Vila Madalena, open the way for quicker gentrification processes than in Bairro Alto or Gracia, and eventually cultural activities soon will move from there, like in many other cases around the world). In some cases these issues are being actively considered in the public policies (e.g., intermediary uses policy in Kreuzberg). Not discussing here the merits and consequences of these particular actions, we just want to highlight that the complex mix of specific governance mechanisms that embed and are at the roots of each case, are a key-issue for its sustainability, and local stakeholders (and external policy agents, however well-intentioned they may be) must take that into account in their strategies, and be very careful with it, as the understanding and the management of this complexity is fundamental to the long term sustainability of the creative dynamics on those areas.

5. Concluding note

This paper’s objective was to explore the relation between urban design, public space appropriation and the informal dynamics taking place on creative milieus, from an international comparative perspective. Based on an empirical approach to urban morphology, everyday life and symbolic public space appropriation on ten creative districts around the world, we identified the main dimensions which were considered essential to embed and to support the development and sustainability of these creative milieus.

An empirical work supported on literature review, visual recollection and participative observation, allowed us to systematize for each one of our ten case studies their situation regarding each one of these key-factors: (i) the importance of the “classical” factors (dimension, density, heterogeneity); (ii) the relevance of the area’s symbolic capital; (iii) the physical and symbolic centrality of the quarter in the city; (iv) the morphological conditions of the area; (v) the relevance of conviviality and nightlife and their relation with the creative milieu; (iv) the local presence and relevance of art world’s reputation mechanisms; (vii) the main use conflicts and the way they condition the evolution of the territorial system; (viii) the informality mechanisms and their presence on public space; and (ix) the role of specific governance mechanisms.

The use of this grid permitted us to validate the generic importance of all these factors, each one standing out as crucial to the majority of the case studies, although with variable relevance in each situation. Historical, cultural, social, economic and institutional factors, alongside urban design and morphology, naturally condition each situation, and some of these factors assume sporadically less importance in one or two specific cases, but we can admit that all of them can generically be considered undeniably relevant to the dynamics and sustainability of “creative milieus”.

This was expected to provide a contribution towards the development of a new planning agenda for dealing with urban creative dynamics and cultural quarters. In effect, the attendance of these criteria when dealing or intervening with territorially-based creative dynamics, seems to be fundamental. And this does not mean that each one of them can be fabricated for each intervention by urban planners, private investors or public authorities; instead, this points to the fact that each territorial system must been understood in all its specificities and in all its diverse potential. Then, these key factors should be valorized and worked with the local actors, seizing specific governance mechanisms, articulating stakeholders’ interests, managing their internal use conflicts, and understanding the vital importance of the symbolic system and place representation, for the diverse users of the quarter and the multiple art worlds. Places open to informality, giving freedom for less formal action and providing space for liminality, avoiding the excesses of institutionalization, seem to be the key for a successful planning activity, as demonstrated in these case studies. For instance, many of the small artistic interventions on urban space or initiatives based on appropriation of local public spheres promote a vitality and an authentic connection to place and local dynamics which are much more consequent in terms of effectiveness and long term sustainability for local development than more “conventional” or “institutional” “creativity rhetoric”-led initiatives, branding creative quarters, supporting the attraction of creative people or promoting emblematic facilities or flagship events. And they are much more affordable for planning authorities as well...

The dimensions that we suggest in our analysis represent a first step in order to propose a typology of urban cultural districts. Further research will enable us to develop these multiple analytical dimensions, conceptually and empirically, with the aim of stabilizing a set of typological criteria which enable us to typify urban cultural districts according to this multiplicity and complexity of dimensions.

References Alexander, C. (2011), “Making Bengali Brick Lane: claiming and contesting space in East London”, The British Journal of Sociology, Vol. 62, Issue 2, pp.201-220.

Antupit, S., Gray, B., Woods, S. (1996), “Steps ahead: making streets that work in Seattle, Washington”, Landscape and Urban Planning, Vol. 35, Issues 2–3, August, pp.107-122.

Arantes, A. (1997), “A guerra dos lugares: fronteiras simbólicas e liminaridade no espaço urbano de São Paulo”, in C. Fortuna (org.), Cidade, Cultura e Globalização – Ensaios de Sociologia, Oeiras, Celta, pp.259-270.

Bader, I., Bialluch, M. (2009), “Gentrification and the Creative Class in Berlin-Kreuzberg”, in L. Porter, K. Shaw (eds.), Whose Urban Renaissance: An international comparison of urban regeneration strategies, Routledge, pp.93-102.

Balula, L. (2010), “Espaço público e criatividade urbana: A dinâmica dos lugares em três bairros culturais”, CIDADES, Comunidades e Territórios, nº20-21, Dezembro, pp.43-58.

Bell, D., Jayne, M. (eds.) (2004), City of Quarters: Urban Villages in the Contemporary City, Aldershot: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Camagni, R., Maillat, D., Matteacciolli, A. (eds.) (2004), Ressources naturelles et culturelles, milieux et développement local, Neuchatel: EDES. [ Links ]

Camors, C., Soulard, O. (2010), Les industries créatives en Île-de-France: un nouveau regard sur la métropole, IAU îdF, Mars. [ Links ]

Cartiere, C., Willis, S. (2008), The Practice of Public Art, New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Caves, R. (2002), Creative Industries: Contracts between Art and Commerce, Cambridge/London: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Cooke, P., Lazzeretti, L. (org.) (2008), Creative cities, cultural clusters and local development, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

Costa, P. (2007), A cultura em Lisboa: competitividade e desenvolvimento territorial, Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

Costa, P. (2009), Bairro Alto-Chiado: Efeitos de meio e desenvolvimento sustentável de um bairro cultural, Lisboa: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa – DPPC.

Costa, P. (2012), “Gatekeeping processes, reputation buiding and creative milieus: evidence from case studies in Lisboa, Barcelona and São Paulo”, in Lazzeretti, L. (Ed.), Creative industries and innovation in Europe: Concepts, measures and comparatives case studies, Routledge, pp.286-306.

Costa, P., Latoeira, C., Lopes, R. (2010), Apropriação, conflitos de uso e produção do espaço público em 3 bairros criativos: uma abordagem fotográfica ao Bairro Alto, Gracia e Vila Madalena, DINAMIA’CET Working Paper, WP 07/10.

Costa, P., Magalhães, M., Vasconcelos, B., Sugahara, G. (2008), “On ‘Creative Cities’ governance models: a comparative approach”, The Service Industries Journal, Vol. 28, n.º3-4, April-May, pp.393-413.

Costa, P., Vasconcelos, B., Sugahara, G. (2011), “The urban milieu and the genesis of creativity in cultural activities: An introductory framework for the analysis of urban creative dynamics”, CIDADES, Comunidades e Territórios, n.º 22, Dezembro, pp.3-21.

Costa, P., Lopes, R. (2011), “Padrões locativos intrametropolitanos do cluster da cultura: a territorialidade das actividades culturais em Lisboa, Barcelona e São Paulo”, REDIGE – Revista de Design, Inovação e Gestão Estratégica, Vol. 2, n.º 2, pp.196-244.

Costa, P., Lopes, R. (2012), “Urban design, public space and the dynamics of creative milieus: a photographic approach to Bairro Alto (Lisboa), Gracia (Barcelona) and Vila Madalena (São Paulo)”, DINAMIA’CET WP 12/18.

Dias, S. (2010), Um percurso histórico por 3 bairros criativos: a identidade e a formação morfológica urbana. DINAMIA’CET WP 11/10.