Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

CIDADES, Comunidades e Territórios

versão On-line ISSN 2182-3030

CIDADES no.31 Lisboa dez. 2015

https://doi.org/10.15847/citiescommunitiesterritories.dec2015.031.art07

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Vernacular Aesthetics in Self-Built Housing in Tunis and Cairo.

Estética Vernacular na Auto-Construção em Tunes e no Cairo.

Leila KhaldiI

[I]Centre de Recherche sur l'Habitat, France. e-mail: leila.khaldi@gmail.com.

ABSTRACT

Exterior house aesthetics are generally considered as the task of professional architects and urban planners. However, in Maghreb countries, and in other developing countries as well, self-made non-professional inhabitant builders assure the city growth. My research – as an architect – aims to acknowledge and understand the meaning of vernacular contemporary aesthetics that are free from academic models and urban regulation policies. The research draws on the observation of individuals and mass housing in various popular neighborhoods of Tunis and Cairo, using photography, graphical analyses and interviews. My main hypothesis is the recognition of the inhabitants competence to produce their own aesthetics that are visible through the front buildings. This paper will discuss how the inhabitants perceive the outside aspects of the house, and the way it affects its external appearance.

Keywords: Façade, aesthetics, popular, self-built.

Introduction

Formal contemporary architectural production represents only 35% of the Tunisian built environment (Leila Ammar, 2011). In Greater Cairo, 63% of the population inhabits informal or extralegal settlements (Sims, 2012). In both cities, more than half of the housing is fabricated outside the formal paths of architectural and urban production. We can easily presume that this is the case in most of North African cities. Architects and urban planners are directly concerned as they have faced particular challenges in the process. Although Tunisian self-built housing has caught the architects attention since the early eighties[2], it has been done mostly with a concern for technical aspects such as land regularizations, water and electricity supplies, street lightings, and social equipment. Meanwhile, both formal architecture and traditional vernacular have been studied and described since the beginning of the twentieth century in Tunis (Revault, 1971; Revault, 1978; Saladin, 1908), as well as in Cairo (Revault, 1975; Migeon, 1907). While books and researches on the informal settlements upgrade (Chabbi, 1986a ; Chabbi, 1986b; Kahloun, 2014) and the traditional architecture exists, documentation about aesthetics of the self-built houses and transformed public housing is lacking. Through my own personal experience, I noticed that the professionals judge negatively the external aspect of self-built houses without giving any further interest; thus, through inspecting the inhabitants built environment, these professionals testified their depreciation regarding the inhabitants skills to build. In 1994, Deboulet defended the idea that the inhabitants of informal areas in Cairo had the capacity to build their own frame of life, by considering it as a town planning of popular emanation. To my knowledge, this type of study is still missing in Tunisia.

The aim of this research is to understand the meaning of modern vernacular aesthetics[3] of self-built habitations and appropriated social housing units. Although my research principally occurred in Tunis, it has been enriched by a two months stay in Cairo where I fully devoted my time for the observation of the Egyptian popular neighborhoods. I wanted to move away from the classic study cases of the neighboring countries of Tunisia like Morocco and Algeria, as the comparisons between these countries have already been well explored from the urbanistic, architectural and social point of view (Ammar, 2011; Bacha, 2011; Le Tellier, 2010; Marçais, 1954; Santelli, 1987). I chose to stray slightly towards another close country. I believe that the decoration mechanisms present some similarities despite the differences between Tunis and Cairo in terms of city scale, urban processes, building types, and even expressions of decoration. The research will allow highlighting the diversity of appropriations and expressions, within the framework of a market that, I suppose, is globalized.

I resorted to the inhabitants to try to understand how they usually proceed to make their aesthetics, refraining myself from making à priori value judgments. To this end, I am adopting the aesthetic reception theory of Jauss[4] who considered that the aesthetic experience – in literature and art – had to include not only the work, but also the way the reader received it and the artists working conditions. Thus, the exterior aesthetics are to be considered as an interaction between the inhabitants material and their living conditions, the representations of good and bad taste, and the consumption of ornamentation products on a globalized market. These considerations are to be linked to social standards of the era we are living in.

This paper will discuss how the inhabitants perceive the outside aspects of the house and the way it affects its external appearance. First, my investigation methodology will be exposed; it will be based on the collection of the inhabitants appreciations and perceptions on a series of iconography. The first results will be shared[5]. I will also make a brief comparison between the two cities in terms of decoration elements, in order to illustrate the contents of the markets and point out come similarities and differences.

Methodology

Interviewing the inhabitants in Tunis

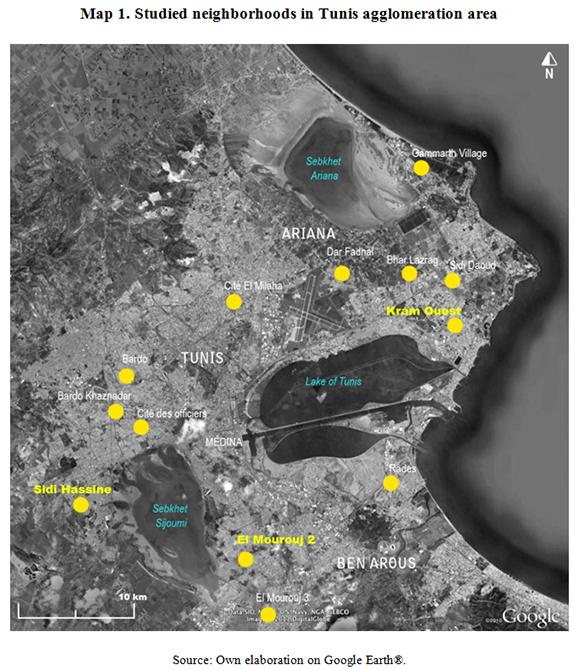

As it was said earlier, the dominating housing type in Tunisia is individual housing. Whenever there is a legal construction, the owners have to submit a plan[6] of the house in order to get a building permit delivered by the municipal services. Once obtained, it often happens that the plan is modified as the construction evolves.[7] 113 inhabitants of 15 neighborhoods in Tunis agglomeration area (map 1) were interviewed. The main selection criteria of the neighborhoods were the absence of architect in the process of edifying houses. The interviewed owners had low or middle income. The districts they live in are all relatively new, as they began to appear between the seventies and the nineties. I chose the semi-structured interview method in order to collect qualitative information based on the inhabitants speech (Raymond et al., 1966; Segaud and Raymond, 1981).

The inhabitants first had to choose between 28 façades of different styles and 270 front houses decoration elements, and express their comments. The façades and ornamentation elements were drawn from the formal based architecture as well as from the contemporary vernacular; most of them can actually be seen in the urban agglomeration of Tunis. The elements were divided in nine categories: doors, windows, cornices, floor and wall coverings, columns, arcs, guardrails, acroterions, and other details (plants, stairs, etc.). The elements were mixed and presented in a-thirty-page sorter, placing nine elements by page. The second part of the protocol consisted of coming back once again with an A3 format printed picture of the façade. The inhabitants were asked to imagine what they would change in their front house if they had the chance to do so, choosing from the selection of the provided decoration elements. Among all the interviewed persons, only 30 accepted to take the second part of the interview. They saw an opportunity to think about the changes they would do especially after learning from the mistakes of the past. Some were simply not interested to continue, and gave various reasons like the lack of money or time.

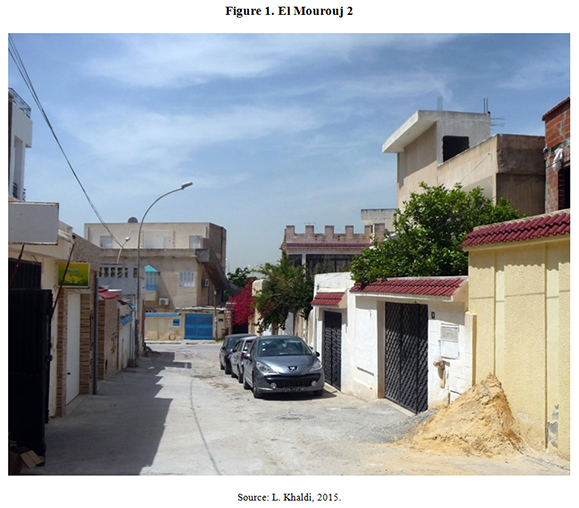

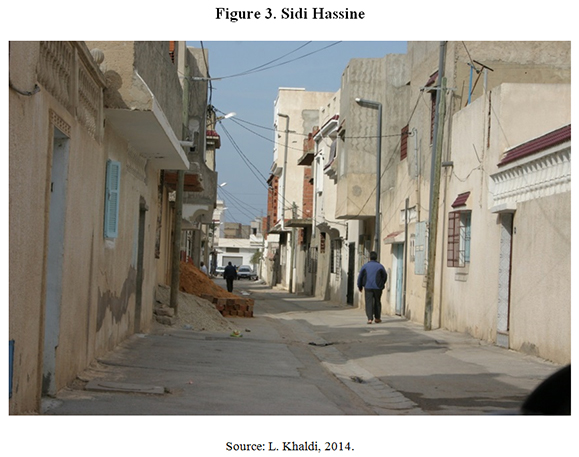

Given the progress of the collected data processing, I will focus on the inhabitants sayings of 3 neighborhoods for the purpose of this article: El Mourouj 2, Kram West and Sidi Hassine. Respectively located in the southern, eastern and western part of Tunis agglomeration area, they recover of different urban processes.

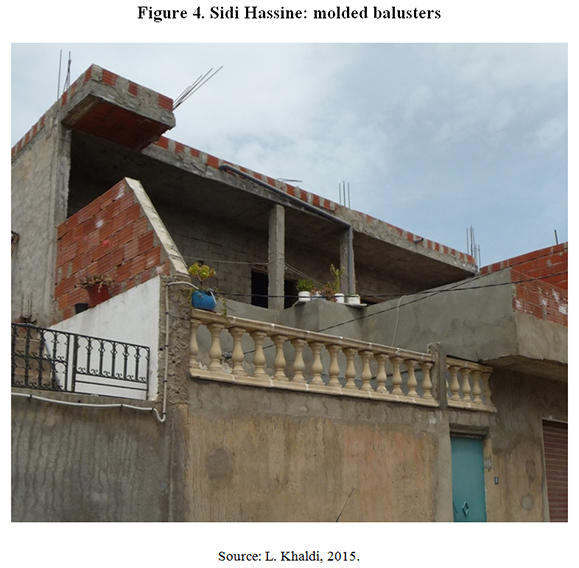

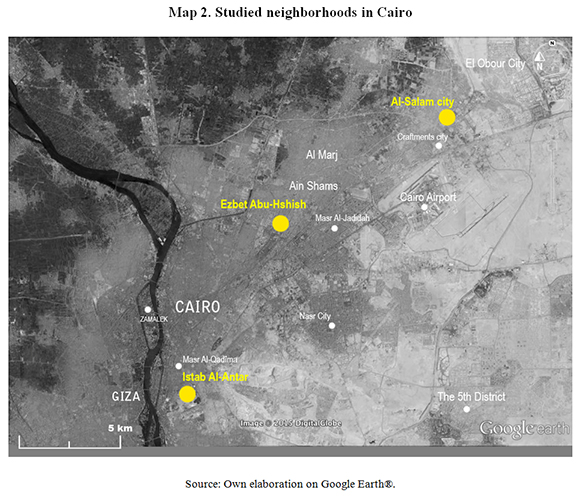

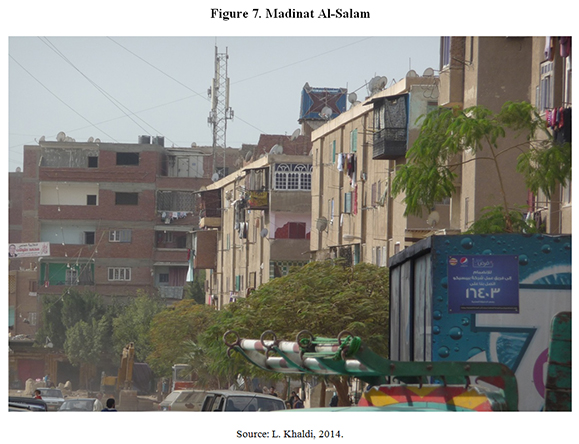

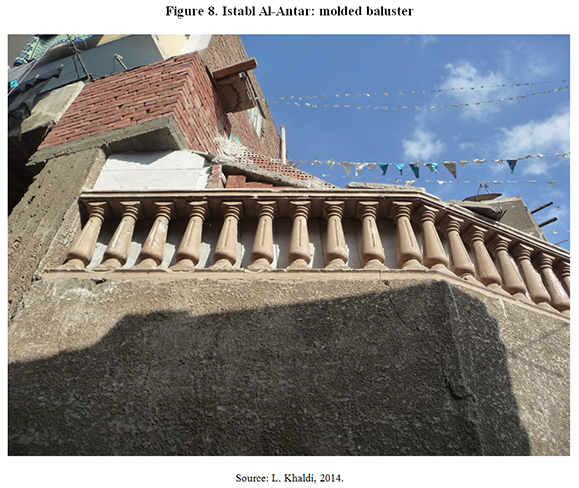

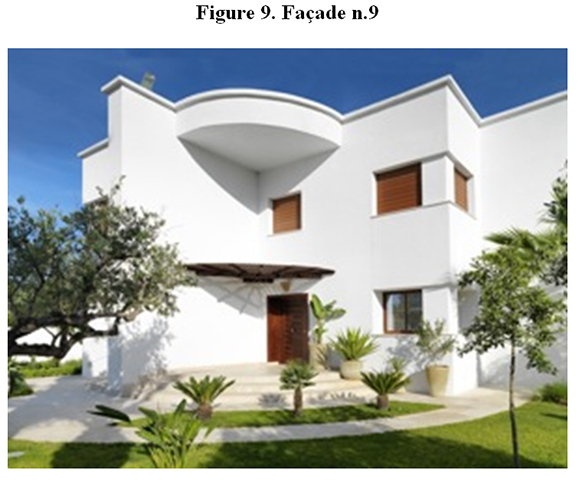

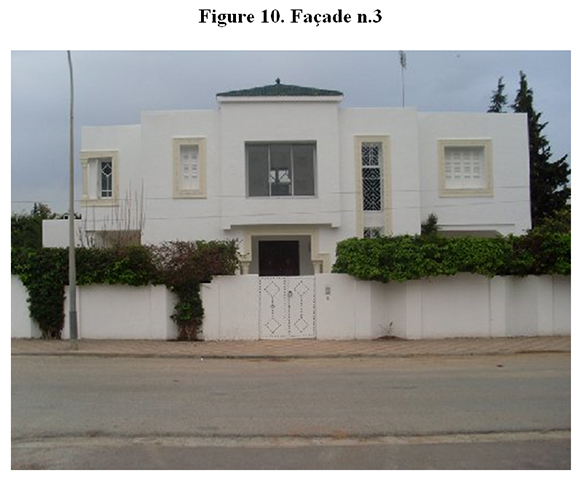

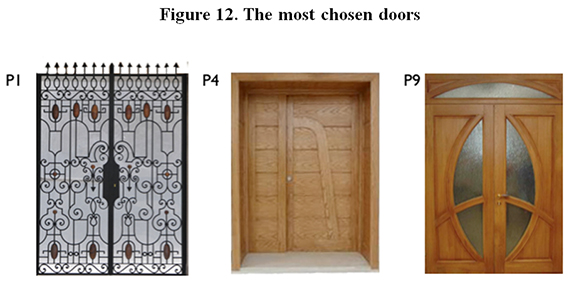

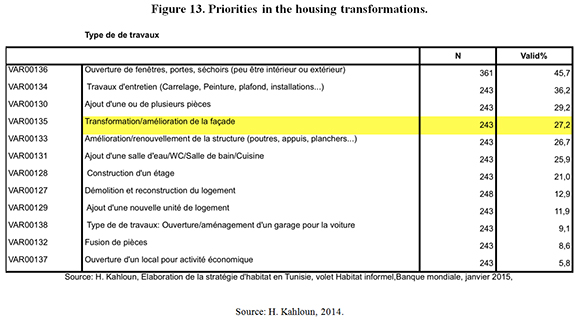

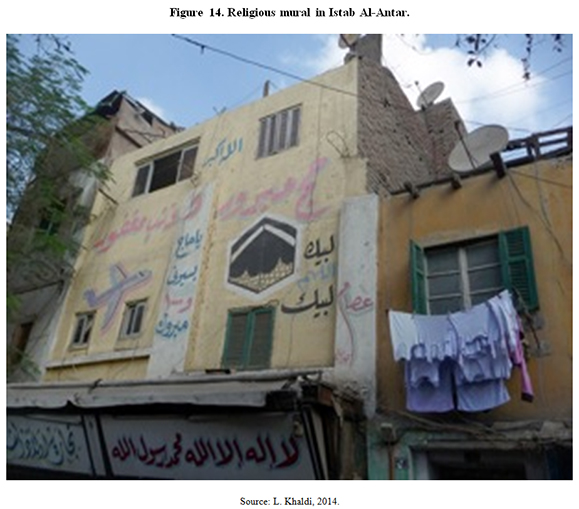

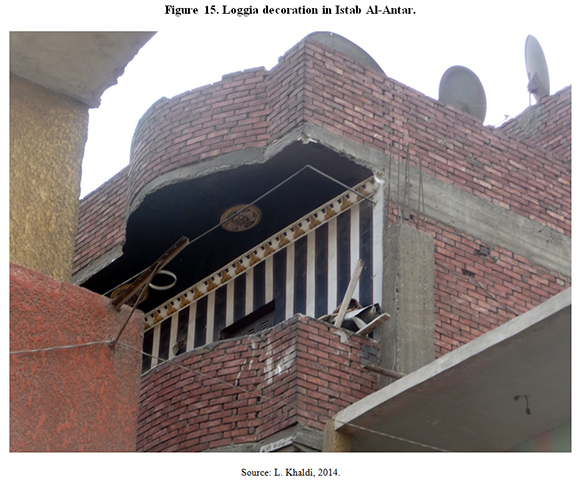

l Mourouj 2 (Fig.1) is a result of a public initiative destined to solvent populations, which consisted in providing building plots for private, semi-private and collective housing. Kram West area (Fig. 2) is a public operation of rehousing of the 80s, destined for the inhabitants of the degraded dwellings nearby. The planners provided basic ground floor houses, and gave the inhabitants the possibility to make extensions by themselves (up to two levels). A household, from the extended family or tenants, occupies each floor. Contrary to the other areas, Kram West is well connected to the rest of the city, and located closely to the historical areas of Carthage and Sidi Bou Said. Sidi Hassine (Fig. 3) is an informal peri-urban area where populations stemming from rural migrations became established in the 70s. Today, most of the houses in Tunis have a first floor, and sometimes, a second. Observing popular neighborhoods in Cairo In parallel to my work in Tunis, I had the opportunity to observe three neighborhoods during my stay in Cairo: the informal areas of Istab Al-Antar (Ezbet Kheirallah district) and Ezbet Abu Hashish (Hadayeq Al-Qobba disctrict), and the public housing area of Madinat Al-Salam (Al Obour) (Map 2). These districts showed great interest since they come from of original urban processes and specific types of dwellings, while showing similarity in the decoration of the façades. Systematic photos of the buildings have been taken, focusing on the ornamentation of what we designated as loggias. During these last decades, and contrary to Tunis where the individual housing dominates widely, in Cairo we find instead public and private mass housing edified by the State itself, private promoters or "small entrepreneurs of the informal" (Panerai et Noweir, 1990). I noticed that decorations could be identical whether the area has been planned or not. The studied areas are located in the eastern shore of Cairo, respectively the center, the northern and the northeastern periphery of the city. Both first two areas are called ishwayyat, as they arose from the informal. Istab Al-Antar (Fig. 6) for example, was a vast totally empty space until 1980 (Deboulet, 1994), and has known successive periods of urbanization as migrants came from Upper Egypt. The same goes for Ezbet Abu Hashish (Fig. 5). As Panerai and Noweir (1990) said, informal areas present a certain unity of the façades, due to the use of the same materials, constructive structures, and distributive plans whatever the surface of the apartment is. The buildings façades are not painted, and their heights can go up to ten floors. It is the loggias of the apartments that are decorated once occupied by the inhabitants. The third area, Hay El-Salam, was the initiative of a public operation of the rehousing (masakîn chabiyya) of the nearby shantytowns populations. It is a dormitory town with standard apartment blocks – with loggias – of 4 or 5 floors (Fig. 7). I tried to link these decorations with the existing products on the market, the techniques – especially for the paintings – and the origin of the migrants, which are essentially from Upper Egypt (Deboulet, 1994; El Mouelhi, 2014). I noticed that there are a number of recurring elements in the buildings in both cities. The example of Cairo showed that the use of some prefabricated elements – such as cornices, rosettes of ceiling, balcony rails and columns - is common, despite the differences with Tunis in terms of city scales and housing typologies. It testifies of a market of products within the reach of low-income populations. In fact, there are small shops displaying different kind of molded products on the edge of the roads both in Tunis and Cairo. The façade and the house As I have already chosen global images of houses and elements and already commented on them with the Tunisian inhabitants, this allowed me to offer precisions about the representations of the external aspect of the house. The façades and the elements were chosen according to several criteria that were deducted from the inhabitants speech in Tunis. The size of the house The global houses images submitted to the inhabitants were mostly judged in terms of "the size of the ground", "space between the house and the enclosing wall", "vegetation" and "presence of a garden". The fact that the house was isolated and not coupled has been well appreciated. The impression that the construction was "open" and "airy" was also a criterion of choice. Some of the inhabitants though spoke about the "style", whether it was "good" or "bad", and whether they liked it or not. At this scale, the interviewees did not formulate specific comments about the ornamentation, but rather about the house in general, its size, typology and configuration. Figure 7. Façade n.9 "This one is very simple

gorgeous" (woman, 54, El Mourouj 2) "Id like to have a detached house with space and a garden

A place to see the kids play

I prefer not to have a semi-detached house

I couldnt manage to plant a garden here

I had a little garden but I removed it so that we can park cars

" (woman, 52, El Mourouj 2) Figure 8. Façade n.3 "Its smooth

I dont know why it attracts my attention

I feel peace

there is a large garden I think" (man, 63, El Mourouj 2). Figure 11. Façade n.8 "I really like this one because I can accommodate a swimming pool

I can do many useful things

make a pool would be the first thing to do" (women, 32, Kram West) "I like it because the sun shines through the whole house

it is ventilated

I want to feel the breeze from everywhere" (woman, 56, Kram West). Therefore, I can say that the ornamentation does not draw the interviewees attention at first, and may deduct that the space layout surrounding the house seems to be more important than the decoration of the façade, given the fact that they expressed their opinion on the intermediate spaces, which, according to my interpretation, confers quality and value to the habitation. The influence of spatial context On the other hand, certain façades were qualified as good because they were connectable to a spacio-temporal context. These façades marked the stamp of specific cities like Sidi Bou Said, Medina or the colonial downtown. Considering that "outside of their context, they would be meaningless" referring to a certain historical context, they would not recommend to do the same thing in the neighborhood or in their own house: "there are façades in Sidi Bou Said that are very nice

but if they were put elsewhere

they would be irrelevant. The same goes for the ancient town gates of the Medina"(man, 63, El Mourouj 2). Others connected some façades to the upper class districts, saying such houses "could not go well in a popular neighborhood like ours". It was suggested that the conformity with the rest of the neighborhood attracted less attention and preserved the intimacy. Beyond the spatial and temporal context, the discretion concern seems to be related to social convenience. Criteria tied to everyday life The cost of the doors and windows appeared to be one of the most important criteria, as well as the cost of their maintenance. Considering the effort to keep certain materials clean and in a good condition such as wood; aluminum windows were preferred for the front house, whereas wood windows were chosen for the kitchen because it is "more preserved from the street" (when it is located at the back of the house). The testimony also contains some indications about a domestic hierarchy of the elements, according to the resistance of their materials: the "strong" ones are placed outside, and the weak ones inside. The metallic doors (such as P1, Fig. 12) were chosen for the enclosing walls, as the safety matter was evoked. The door P4 was chosen for the second entrance, and P9 as a "separation between the lane and the lounge". The size and decoration of the main exterior door also seemed to be valued. It may be part of a heritage of ancient times, when the door carried the only exterior signs of distinction in the façade. What the inhabitants see in the neighboring houses also influences their choices: "this is the same door as in my sisters house, I like it" (women, 45, Kram West); "I noticed this type of covering, it is sold at the market nearby[8]" (man, 63, Sidi Hassine). It appears here that the preference for certain elements is linked to the daily practices experienced in the domestic and urban space. The temporality in the contemporary vernacular housing project The place of the façade in the housing project The façades often look unfinished, with vertical reinforcing irons, concrete ceilings and beams, and apparent brick walls. However, the ground floor can be painted and decorated once the interior furnishings are set up. The closing wall can be painted in white or in different colors, as it can be covered with stucco, or with stone-like cladding panels. The outcomes of the World Bank survey about the informal housing in Tunisia (Fig. 13) tend to confirm the priority of the internal layout compared to the façade. It shows that the number of façade improvements comes in the fourth position, after the opening of windows and doors, maintenance work such as covering floor or interior installations, and the addition of another room. Additionally, in the agglomeration area of Tunis, the transformation and improvement of the façade comes after the construction of an additional floor, and the creation of a kitchen or a bathroom[9]. This may suggest that the outside aspect of a house and its volumetry is mainly the result of an internal layout, which aims to be as comfortable as finance can allow. The decoration of the façade comes after, and consists in painting and adding prefabricated elements. The second part of the interviews allowed verifying the inhabitants perceptions of the façade arrangement in the global temporality of the house edification, by imagining the transformation of their existing façades. The inhabitants testimonies and my own observations tended to confirm that the decoration of the façade might not be a major priority in the chronology dedicated to the construction of the house. It comes after the concern of the domestic comfort, and the layout of the intermediate spaces. Nevertheless, some of them seemed eager to make some exterior arrangements, despite the lack of money: "I shall put some tiles like this in terrace of the ground floor

" (Woman, 65, Kram West) "We have a small patio behind the house, we could make a winter garden

" (Man, 68, El Mourouj2) "I like this one, it is my taste

but it is not only a matter of taste

who doesnt wish to have a beautiful, decorated house? Its a matter of money!..." (Woman, 54, El Mourouj 2) Learning from previous experiences Some inhabitants showed a certain learning from their previous experience of construction, and do not want to make the same mistakes: "Id like to do it here by the window

Im clearly referring to the first floor only and not to the ground floor

this latter is finished and the windows are wooden, I cant demolish now

however, upstairs, Ill make aluminium windows" (women, 47, El Mourouj 2). "The aluminum is expensive, but the maintenance of the wood it is even more expensive

I would have preferred to have metallic windows from the beginning

" (Woman, 54, Sidi Hassine) On the other hand, as the edification of a first or a second extension floor may happen after a long time – sometimes up to 10 or 15 years –, some elements may no longer exist on the market, leading to a different decoration between two floors. The local-global dialectic The global-local dialectic is complex and difficult to grasp. At this stage of my research, it seems however likely to supply some elements of understanding as for the contemporary popular aesthetics. The circulation of tools for manufacturing of industrialized products illustrates the aspect of the globalization in the aesthetics fabrication. There are common building materials and construction techniques, as well as ornamentation implementations not only in both cities, but also and in a larger scale. However, stylistic differences exist. The plaster elements such as cornices, rosettes of ceiling, balcony rails and columns are just as common in both cities. All are made from plastic or iron molds, but they are shaped differently according to local ancient styles. The metallic doors separating the house from the street is also widespread[10], but the decoration paths may differ again. The paintings are also available everywhere, but the colors can somehow be very different, as they appear light in Tunis and lively in Cairo, sometimes with patterns or religious mural paintings (Fig. 14) (Fogel, 2007)[11]. I also noticed the recurrence of some design paths in the loggias of the three neighborhoods I visited in Cairo. Wondering what the covering techniques were, I learned that stencils with floral motives were available in the markets and painting stores. Stamps with floral motives can easily be found too and some of them are imported from Europe. Scotch tape is used to realize geometrical designs, as well as vertical strips that look like wallpapers (Fig. 15). It is not the case in Tunis, where the exterior walls aspects tend to be more discrete. There are resemblances here and there, due to the production and the use of similar prefabricated elements, but there are also differences in the colors and styles. Certain products are made locally within districts (craftsmen and small manufacturers), and others are imported, such as stencils with motives for example. The stylistic variations are – among other factors - connected with the cultural background and media influence, but we do not know very well in which proportions. The traceability of the formal elements is a complicated operation, but the question deserves to be asked and it is part of my investigation. The circulation of the references and the conditions of production (local or imported products) is a matter of a global / local dialectic that has to be encircled more clearly afterward. Beyond the comparison between the cities, it may also be useful to look at the similarities and differences between popular and upper residential areas in terms of ornamental vocabulary, in order to better understand the global / local dialectic. For example, light mural colors are common in all Tunis houses, whereas, bright mixed colors happen to be specific to Cairos popular neighborhoods. One should think about the reason why stencils, for instance, have more success in Cairos popular neighborhoods. Several observations of this kind can be made, which leads to consider the inhabitants as consumers, and question their attitude towards the market. Conclusion: towards a more accurate vision about popular aesthetics It seems rather difficult to understand the self-built aesthetics from the architectural culture criteria. The time of the architectural project is reduced and supplies a synthetic view of the outside aspect of the construction. The façade is constructed according to principles such as symmetry and proportions, and designed in advance. On the contrary, the popular aesthetics are not supported by iconography, but rather by the know-hows of the craftsmen and the masons who advise and collaborate with the owner. The house is built in a longer time, according to the available finances. Meanwhile, the decoration market evolves and the previous elements are no longer available, leading in some cases to a different ornamentation between floors. The inhabitants are also likely to make different choices when building a new floor, as they learn from past experiences. The domestic comfort is certainly prioritized in this process, but it is a matter of time before the external aspect becomes important. The production of the contemporary vernacular housing environment exceeds the strict frame of the auto construction, integrating aesthetical references that circulate on an international scale. We may say that the vernacular housing environment is characterized more and more by the use of prefabricated elements, although stylistic differences exist. The observation of the decorations signs may seem secondary compared to the sanitary priorities and living conditions of the inhabitants. However, they appear to be meaningful because they inform us about the contents and the extension of a consumer market and shared know-hows. They also suggest that the precariousness of the living conditions do not prevent the appropriation of the built space, by marking and manufacturing certain aesthetics. We are in the presence of a new aesthetics made of hybridizations and an interbreeding of former and modern references, which inspire fabricants in order to answer the inhabitants / consumers requests in terms of ornamentation products. On the other hand, the inhabitants have the capacity to choose their decorations, according to their everyday life needs, by accommodating several criteria of various orders (practical, economic, social and cultural). REFERÊNCIAS Ammar, L. (2011), « Discours, pratiques et références de larchitecture savante à Tunis, limmeuble contemporain en question », in M. Bacha, Architectures au Maghreb (XIXe et XXe siècles). Réinvention du patrimoine, Tours : Presses universitaires François-Rabelais, pp. 283-300. [ Links ] Ammar, L. (2011), Formes urbaines et architectures au Maghreb aux XIXe`me et XXe`me sie`cles, La Manouba : Centre de publication universitaire. Bacha, M. (Ed.) (2011), Architectures au Maghreb (XIXe-XXe siècles): Réinvention du patrimoine, Tours: Presses universitaires François-Rabelais. [ Links ] Chabbi, M. (1986a), Lhabitat spontane´ pe´ri-urbain dans le district de Tunis (Vols. 1–2), Tunis, Tunisie: Ministère de lintérieur. Chabbi, M. (1986b), Une nouvelle forme durbanisation a` Tunis: lhabitat spontane´ pe´ri-urbain (Thèse). Créteil, Val-de-Marne: Institut durbanisme de Paris. Deboulet, A. (1994), Vers un urbanisme de´manation populaire: compe´tences et re´alisations des citadins?: lexemple du Caire, Paris: Institut dUrbanisme de Paris. El Mouelhi, H. (2014), Culture and informal urban development. The case of Cairos "Ashwa"eyat, Berlin: University of technology. [ Links ] Fogel, F. (2007), « Des voyageurs immobiles. Pratiques communautaires autour du pèlerinage (Haute Égypte) », Théologiques, 15(1), 19. http://doi.org/10.7202/017630ar [ Links ] Frey, J-P. (1988), Refaire de la forme urbaine, Université de Paris 10 Nanterre, Laboratoire de Géographie Urbaine, 1988, no 12/13, (coll. « Formes urbaines »), p. 202-214. [ Links ] Kahloun, H. (2014), Habitat Informel. Diagnostics et recommandations, Retrieved October 23, 2015, from http://www.mehat.gov.tn/fileadmin/user1/doc/Contenus/FR/HabitatInformelRapportIntermEdiaireProvisoireHKahlounOct2014.pdf [ Links ] Le Tellier, J. (2010), « Regards croisés sur les politiques dhabitat social au Maghreb?: Algérie, Maroc, Tunisie », Lien social et Politiques, (63), 55. [ Links ] Loubes, J.-P. (2007), « V comme vernaculaire contemporain », Les Cahiers de La Recherche Architecturale et Urbaine, (20/21), pp.170-175. [ Links ] Marçais, G. (1954), LArchitecture musulmane dOccident. Tunisie, Algérie, Maroc, Espagne, Sicile. Arts et métiers graphiques, Paris. [ Links ] Navez-Bouchanine, F. (1990), « Usage et appropriation de lespace dans les quartiers résidentiels de «?luxe?» au Maroc » in Habitat, État, société au Maghreb, Paris : CNRS Éditions, pp. 281-298. [ Links ] Panerai, P., Noweir, S. (1990), « Du rural à lurbain », Égypte/Monde arabe (1), pp. 97-124. [ Links ] Raymond, H., Haumont, N., Raymond, M. G., Haumont, A., Lefebvre, H.(1966), Lhabitat pavillonnaire. Paris: Centre de recherche durbanisme, Institut de sociologie urbaine, Ed. [ Links ] Revault, J. (1971), Palais et demeures de Tunis (2): XVIIIe et XIXe siècles, Centre national de la recherche scientifique & Institut darchéologie méditerranéenne, Eds, Paris: Éditions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique. Revault, J. (1975), Palais et maisons du Caire du XIVe-XVIIIe sie`cle (Vols. 1–2), Le Caire, Egypte. Revault, J. (1978), LHabitation tunisoise: pierre, marbre et fer dans la construction et le décor, Paris: Éditions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique. [ Links ] Saladin, H. (1908), Tunis et Kairouan, Paris: H. Laurens. [ Links ] Saladin, H. J., Migeon, G. (1907), Manuel dart musulman (Vols. 1–2). Paris: A. Picard. [ Links ] Santelli, S. (1987), « Évolution et ambiguité de la maison arabe contemporaine au Maghreb?: étude de cas à Rabat et Tunis », in Espace centré: figures de larchitecture domestique dans lOrient méditerranéen, Paris: Parenthèses. [ Links ] Segaud, M., Raymond, H. (1981), « Code et esthe´tique populaire en architecture », in B. Huet (Ed.), Concepcion de lespace, Paris: Institut détudes et de recherches architecturales et urbaines, Ministère de lenvironnement et de cadre de vie, Direction de larchitecture. Sims, D. (2012), Understanding Cairo, The logic of a city out of control, Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. [ Links ] Notas [2] The public authorities have implemented various tools of regulation and urban action plans: Plan de Développement Urbain PDU (1983), Programme National de Réhabilitation des Quartiers Populaires PNRQP 1-4 (since 1992), Plan de Développement Urbain Intégré PDUI (from 1993 to 2006). Source: Agence de Réhabilitation et de Rénovation Urbaine. The national public real estate operator - Société Nationale Immobilère de Tunisie, 1969 - also created replacement dwelling projects to relocate some of the informal areas inhabitants. [3] Or contemporary vernacular, as defined by (Frey, 1988) and Loubes (2007). It qualifies the process that is free from a specific work of project management formalized by plans and iconography. [4] Jauss, H. R. (1978). Pour une esthe´tique de la re´ception. (C. Maillard, Trans.) (Gallimard). Paris, France. [5] It is about sharing first results scattered, the analysis of collected data is in progress. [6] Which is supposed to be made by an architect. [7] Based on the data collected during the investigation on a sample of 113 inhabitants of Tunis agglomeration area in 2014-2015. [8] The interviewee refers to a close district named Ezzahrouni, known by its wide market of cheap decoration items. The market occurs on Sundays. [9] Specific data correlation made by H. Kahloun for the purpose of this paper (June, 2015). [10] It is also observable in the upper class houses in Morocco (Navez-Bouchanine, 1990). [11] Murals are drawn on some ground floor walls and loggia walls, informing that the inhabitant made the pilgrimage in Mecca (Hajj). F. Fogel showed it is a practice that came from rural Egypt. Supposedly, the migrants that came from Upper Egypt brought it to the informal areas of Cairo.