Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

CIDADES, Comunidades e Territórios

versão On-line ISSN 2182-3030

CIDADES no.34 Lisboa jun. 2017

https://doi.org/10.15847/citiescommunitiesterritories.jun2017.034.art04

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Short-stories about time in the making of participatory projects

Breve histórias sobre o tempo na realização de projetos participativos

Luísa AlpalhãoI

[I]The Bartlett, University College of London, Portugal. e-mail: luisa@atelierurbannomads.org.

ABSTRACT

This paper narrates three short stories that occurred during the development of different urban interventions, aka participatory projects for the making of shared public spaces, initiated by atelier urban nomads between 2011-2013. Each of the three projects share the intention of being catalysts for the social and spatial transformation of neglected urban spaces aiming to enhance the life quality of the inhabitants of those territories. Each story illustrates a different approach to time in the development or delivery of the interventions - time becoming a core element for an understanding of the intentions and outcomes of the urban interventions themselves. Together, all stories aim to challenge the ubiquitous paradigm conferred to participatory projects as supposed means of exerting democratic values and of promoting a fairer way to create our built environment. The different stories will scrutinize some of the complexities ingrained in interventions of this nature: participatory and situated at the intersection between art, activism and urban space.

Keywords: Time, public spaces, appropriation & ownership, participatory projects, process, social & spatial legacy.

RESUMO

Este artigo narra três histórias curtas que ocorreram durante o desenvolvimento de diferentes intervenções urbanas, também conhecidas como projetos participativos para a construção de espaços públicos compartilhados, iniciados por nómades urbanos de atelier entre 2011-2013. Cada um dos três projetos compartilha a intenção de serem catalisadores para a transformação social e espacial de espaços urbanos negligenciados visando aumentar a qualidade de vida dos habitantes desses territórios. Cada história ilustra uma abordagem diferente do tempo no desenvolvimento ou entrega das intervenções - o tempo, tornando-se um elemento central para a compreensão das intenções e resultados das próprias intervenções urbanas. Em conjunto, todas as histórias visam desafiar o paradigma omnipresente conferido a projetos participativos como supostos meios para o exercício de valores democráticos e da promoção deuma maneira mais justa de criar ambiente construído. As diferentes histórias examinam algumas das complexidades enraizadas em intervenções desta natureza: participativas e situadas na intersecção entre arte, activismo e espaço urbano.

Palavras-chave: Tempo, espaços públicos, apropriação e propriedade, projetos participativos, processo, legado social e espacial.

Introduction

In this paper I will narrate three short stories that occurred during the development of different urban interventions, aka participatory projects for the making of shared public spaces, initiated by atelier urban nomads in recent years. The atelier was founded by myself in 2010/11 as an artistic and architectural platform whose work brings together architecture, art and design through projects where cities are perceived as playing grounds to create new shared spaces that allow one to read and experience the urban as a collective, social and spatial construction. Most of the work intends to restore the right to the city by raising awareness of ones’ urban environment empowering citizens to claim the city as ones’ own.

From the three presented projects, the two set in Lisbon are also part of my PhD research that expands on the topic of participation for the making of shared public spaces in Portugal. All three projects share the intention of transforming neglected public spaces through the collective making of urban interventions. By doing so, they also intend to trigger new social connections that would ideally lead to the appropriation of these, and other, spaces.

Tactics versus Strategy

All three projects, and most of the atelier’s work, partially draw on the French philosopher and socio-scientist Michel De Certeau’s approach to tactics versus strategy.

In The practice of everyday life, De Certeau states the importance of bringing to light clandestine forms, tactical and makeshift creativity of groups or individuals caught in the nets of ‘discipline’. De Certeau considers these ‘ways of operating’ as the various practices that allow users to claim spaces that had been organized by ‘techniques of sociocultural production’. ‘Production’, as defined by De Certeau, involves a passive ‘making’ and ‘consumption’ omnipresent amongst society, ‘silently and almost invisibly’, becoming evident through the ‘ways of using products imposed by a dominant economic order’. (De Certeau, 1984)

Tactics do not obey the law of a place. They can not be defined or identified by it and can only use, manipulate and divert these spaces. They imply a temporal movement through space and a ‘unity of a diachronic succession of points’ and not the ‘figure that these points form on a space that is supposed to be synchronic’. Technocratic strategies, on the contrary, seek to create places in conformity with abstract models. They involve the ‘calculation (or manipulation) of power relationships’. (De Certeau, 1984: 29-34)

Most of the atelier’s projects are developed with local authorities, other governmental agencies or existing institutions that would have traced their strategies within which one could operate without necessarily complying with all established rules or criteria, identifying loopholes that would allow for less predictable tactical interventions. These then demonstrate how anyone can potentially act beyond the established technocratic constraints finding new ways of operating that reflect uniqueness and diversity in opposition to controlled homogeneity.

Time: ephemeral or incremental growth?

For the purpose of this paper, all stories are linked through the investigation of the role time plays in projects of this nature. Although rarely expanded upon, time is crucial for participatory projects to flourish, as relationships require time to establish, develop and grow. Time will be explored in relation to three different topics: process, participation and legacy, all of which are essential for the making of collective shared urban spaces. However, the socio-economic and political current context imply that in most cases time is scarce, never enough for these participatory projects to have an impact beyond the immediacy of the events (Blundell-Jones, 2005: XV). This view that implies an incremental growth, opposes the current trend of pop-up and other ephemeral projects or interventions of the ‘temporary city’ (Bishop and Williams: 2012). Though it does not negate the value of the ephemeral, it does argue that the project’s temporariness rarely leads to long-term social and spatial transformation.

The context of each of the three stories

The first story, Time and Participation, will explore the notion of time in relation to the development of the participatory project [ a linha ] that took place in Alfama, Lisbon, between 2012 and 2013. [ a linha ] was a proposal to revitalize neglected urban spaces in Alfama through the design and making of a series of street furniture with reclaimed materials. It was selected for the second edition of BIP/ZIP, a programme implemented by Lisbon’s Municipality (Câmara Municipal de Lisboa) in 2011 that supports and funds partnership projects in neighbourhoods in need of an urgent intervention.

The concept BIP-ZIP - Neighbourhoods and Zones of Prior Intervention results from our awareness that though the process of demolition of the shanty towns in Lisbon has ended, urban inequalities have not been eradicated. We went searching for those inequalities and found 67 territories - neighbourhoods, small zones, and sometimes even simply a street - where economic and social difficulties of the people, and urban and environmental problems of the built environment, required an urgent response : « [ a linha ] was a proposal of atelier urban nomads in collaboration with the then three local Juntas de Freguesia, two primary schools and one after school club. The atelier was responsible for managing the budget of €49,500 and ensuring that all activities were developed and implemented according to the plan presented at the application stage which foresaw a two year sustainability programme, but required that all funding would be spent within the first nine months of the project. For the duration of this project and [ jogos de rua ], another BIP/ZIP project that run in parallel with [ a linha ], the atelier employed four assistants and five builders all of whom were local unemployed residents with former experience in construction. » (Roseta, 2013: 13) [2]

Participation is a controversial topic that, according to the critic Markus Miessen and the architectural historian Peter Blundell-Jones, is often romanticized as an ideal of a more democratic approach to the making of architecture and of our cities, or merely as a tick box exercise amongst governmental agencies that recently started having to fulfil a participatory or consultation agenda to sign off projects: « Conventional models of participation are based on inclusion and assume that it goes hand in hand and with the social democratic protocol of everyone’s voice having an equal weight within egalitarian society. Usually, in the simple act of proposing a structure or situation in which this bottom-up inclusion is promoted, the political actor or agency that proposes it will most likely be understood as a ‘good-doer’. (...) Participation, especially in times of crisis, has been celebrated as the saviour for all evil. Such a soft form of politics needs to be questioned. » (Miessen, 2011:15)

However, [ a linha ] has proved, along with other participatory projects, that participation should not be taken for granted and one should not assume that those whose lives and environment would supposedly be enhanced with the participatory projects are willing to be involved, to take action and be proactive. Apathy and lack of interest had already been identified by the philosopher Henri Lefebvre in the 1970s in his publication The Urban Revolution as often present in the development of certain projects: « (…) one of the most disturbing problems still remains: the extraordinary passivity of the people mostly directly involved, those who are affected by projects, influenced by strategies. Why this silence of the part of ‘users’? Why the uncertain mutterings about ‘aspirations’ assuming anyone even bothers to consider them? What exactly is behind this strange situation? » (Lefebvre, 1970:181)

The factor of time to conquer the residents’, authorities and local agencies interest and curiosity had not yet been considered crucial for a change of attitude to occur.

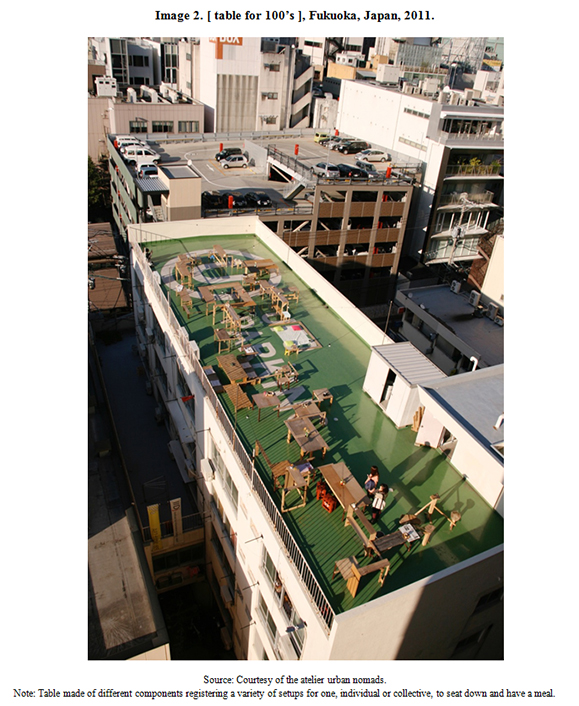

The second story, Time and Event, will look into the project [ table for 100’s ], a temporary urban intervention in Fukuoka, Japan. A very long table that drew a parallel between Portuguese and Japanese food and dinning traditions. [ table for 100’s ] was a project developed as part of the artistic residencies programme ‘Travel Front’ by Konya2023, established in Fukuoka. Konya2023 hosts fully funded artistic residencies every 3 years and [ table for 100’s ] was selected to be developed in the Autumn of 2011. The project was designed by myself with input from the different participants that joined the process at different stages. All were connected to Konya and helped crowdfunding the construction of the table under the limited budget of approximately €2,500. The project lasted three months, from start to completion and the table was built over two days by two skilled local builders solely using reclaimed timber. In November that year we hosted a dinner for over 100 people who sat at our table for that evening. In [ table for 100’s ] the given time for the development of the project was even more reduced, all the focus having been on the opening night when the big table hosted a culturally rich dinner. Time, in this case, relates to an event allowing for a reflection on the role of temporary projects and events as spectacles, mere forms of entertainment as criticized by the Marxist theorist and writer Guy Debord and by the art critic Claire Bishop. These, according to Bishop, do not become catalysts for long term transformation.

Finally, the third story, Time and Legacy, will complete the cycle establishing a connection to the first story about process through the project [ jogos de rua ], a proposal for a mobile playground. [ jogos de rua ] was also a BIP/ZIP project developed between 2012-2013 in PRODAC, Marvila, on the outskirts of Lisbon. It had a budget of €45,950 and, in order to make the most of the available resources, it was developed with the same team as [ a linha ]. [ jogos de rua ] had a youth group connected with Santa Casa da Misericórdia de Lisboa (SCML) as the formal partners, though most dialogue happened directly with SCML, which ran the local nursery and worked as the reference contact between us (atelier) and the local residents. All formal procedures of the project were similar to those of [ a linha ] as it had to fulfil the same parameters established by BIP/ZIP programme, i.e. regular reports, funding reports and completion dates.

This last story will reflect on time in relation to legacy. What remains of these participatory projects in the long-run? Once the projects are completed and all physical evidence is removed, what stays as an immaterial evidence of their presence amongst a community or group of people who were involved in their development?

Methodology

Despite being tailored according to each specific context, all three projects follow a similar methodology. The projects tend to have two phases: a preliminary phase that mostly consists of mapping, meetings with all partners involved, construction of an online archive, photographic and video site documentation, interviews, workshops with the future users (often with local schools) to explore potential ideas through the deconstruction and re-configuration of the material gathered and the festival days where all work done to date is shared with a wider public. The second phase tends to consist of the construction of the spaces collectively designed, and an opening event that culminates the initial process and the project is then handed over to the local partners. Despite not having yet succeeded, the projects intend to be continued after the second phase.

All three stories will come together in the conclusion. Rather than attempting to answer whether or not temporary participatory projects can be considered valuable as urban interventions, the conclusion will draw on the importance of time for their development and long-term social and spatial transformation as they form part of the making of our cities as stated by the geographer David Harvey: « The (…) kind of city we want cannot be divorced from the question of what kind of people we want to be, what kind of life we desire, what aesthetic values we hold. (...) The freedom to make and remake ourselves and our cities is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights. » (Harvey, 2012: 4)

The freedom to make our cities requires a different approach to time, one that is slower, absorbing and giving, more inclusive. Only then can participatory projects contribute to the making of our cities and of ourselves, as citizens.

1st story: Time & Participation:

Alfama was finally buzzing. By the end of May, the hidden storage spaces would have their doors opened and stacks of colourful decoration would be taken out as if one would be preparing for Christmas. The narrow streets of Alfama, otherwise consumed by the decaying look of the buildings, would be filled with colourful flags and ribbons hanging from one window to the other. It was a collective effort to make the neighbourhood sparkle. A sense of pride could be felt in the air. Pieces of timber would be hammered together filling the empty plots with temporary stalls to sell the famous sardines that, by then, had become an indispensable merchandising icon. Fluffy sweet basil would balance the impregnated smell of the grilled sardines dwelling across the city’s old town for the two months of festivities. Old ladies would scream ‘Olhó mangerico!’ to grab our attention so we would touch the leaves of the sweet basil and, allured by their smell, would buy one to take home.

Alfama was ready for the party. So were its’ inhabitants. For once, a sense of community could be felt. Neighbours would help each other, as long as there would be some financial advantage for all. Selling sardines at €2 per fish would cover a family’s living for at least half a year. The community was united in their personal search for profit.

Between the 12th and the 13th of June, packed amongst the crowds as sardines in cans, moving between neighbourhoods proved to be a true challenge taking over one hour to cross 500 metres. There was no joy to be held in such challenge, except for the experience of being part of a collective deed where no social, age or gender boundaries could be felt. Everyone was present and everyone was similar, together we formed a temporary community of those who struggled to move.

Back in December we run the Red Line ‘Festival Day’. On the same spot where ribbons were to be hung in June, next to S. Miguel’s church, a group of young musicians from the neighbourhood came with their instruments to play outdoors. Convincing the teacher it was possible to play the instruments outside on the street appeared to be, by itself, quite daring. In her view, the instruments would most certainly get damaged with the wind, the children could get a cold… various reasons would come to her mind to avoid getting away from her comfort zone. After arduous persuasion, I managed to convince her.

The ‘Festival Day’ had been announced but the posters had not been distributed or advertised. No one knew about the event, so no one came to watch our modest concert. Local residents would walk by, shout at each other as if no one was playing. They would not even look at the unfamiliar, at what was happening. The sound, the instruments placed outside by the church, the children playing became invisible, rather than a pleasant surprise.

Some months earlier, wearing our bright yellow aprons with a bag full of soil inside the equally yellow wheelbarrow, three of us climbed up and down Alfama on a Saturday morning, pushing the wheelbarrow over the bumpy cobbles of the Portuguese pavement, it was the first ‘Festival Day’, the one marking the route of the green line.

Newspaper vases would be filled up with soil, seeds, and a sprinkle of water by those we would meet along our walk through the neighbourhood. A tag would identify the planted variety and the name of those who had sown the seeds. Together, all the vases would be stored in a seeds’ bank so they could eventually be re-potted into the planters we intended to build and which would form new public pockets of greenery which would break the harshness of the concrete voids often encountered around the neighbourhood. The gardens would be made by all who donated a sprout of one of the various lush plants that punctiliously populate Alfama. People looked curious at the sweet, innocent, initiative. They were willing to plant a seed. Being ‘for free’ and ‘uncompromising’, this simple act would mean they had participated in the project, even if they knew little of what it was all meant to be about. They were effectively contributing to the project’s statistics. By the time we reached the flea market at the top of the hill we had used almost all the soil. So we started the next stage of our mission for that day: to glue our large scale paper plants drawn by the children from ATLA, the local after school club, with whom we had been working.

On our way down the hill, we stopped half-way through some of the steps where an old lady was brushing her entrance’s floor. The brush would throw the rubbish away from her doorstep, straight onto what was for her considered public space. Her entrance, despite being outdoors on the street, was ‘hers’ and supposedly private so it needed to be spotless, whilst on the limbo between one step and the other, the rubbish would accumulate. As the wheelbarrow noisily rolled over the cobblestones local residents would peep through their windows to see what was happening.

The crumbling texture of the walls of buildings and stairwells, of playgrounds and abandoned spaces became the canvas for our ‘stick on graffiti’ glued with dissolved PVA. It was a subtle subversive disruption, a call for intervention on those spaces that silently screamed for help. On our way, we were joined by two of the children who had made some of the drawings and who, for a couple of hours, became part of the gang of ‘subversive artists’ under the protection of the municipality.

By the time the planters were finally built few of our seedlings had grown enough to have a visual impact on the streets of Alfama. Inevitably, we had to seek for other plants that were slightly more mature. As the gardening company finished unloading the soil onto the square to be redistributed by the planters now spread across the neighbourhood, the owners of the nearby restaurant drove their Mercedes onto the square, opened the boot and started loading it with our soil which we promptly had to rescue. By the evening we had transplanted beautiful rose bushes that brought colour to the limescale square. The following morning, half of the rose bushes were gone.

Soon after the project’s opening event I received an email from one of the Juntas de Freguesia (local authority) asking me to arrange for the planters to be removed from the main square (Largo do Chafariz) as a popular music concert would soon take place there and the planters were ‘in the way’. Perplexed, I wondered why couldn’t the two - planters and concert - cohabit the same space as, after all, the Junta was a partner of the project and had always supposedly been supportive of the work we had been doing. Yet, [ a linha ] had always been perceived as our (atelier’s) project. Something ‘temporary to embellish the neigbourhood’. The benches designed for all the local residents to use had been given away as ‘gifts’ to one of the local restaurant owners who then used them as storage for the restaurant’s drinks supplies.

[ a linha ] had been participatory in a variety of unexpected ways. It was undoubtedly a participatory success, as our record of unpredicted participants was considerably high even if somehow different from what we had ever envisioned.

The removal of the planters was the first step of the projects’ disintegration. From over twenty small scale local interventions, no more than three or four continued to be used for some months and were transformed and looked after by the local inhabitants. The disintegration resulted from a combination of factors: the fragility of the reclaimed materials we used, poor construction skills of the builders, lack of commitment and maintenance from the Juntas involved, lack of use from the ambassadors (i.e. the schools that had been part of the project), our (atelier’s) exhaustion post project’s completion, vandalism, lack of appropriation from the local residents due to a certain alienation about the project subsequent to the perception of [ a linha ] as being a project of the atelier rather than a collective project, limited involvement from the Juntas and willingness to promote the project amongst existing associations and local groups, our (atelier’s) idealistic approach, difficult (if not impossible) communication throughout the process with all the partners involved and a restrictive budget timeframe by the funders (BIP/ZIP). All of these lead to an accelerated ephemerality of the project.

In this first story I mostly focus on the diversity of participants throughout the making of [ a linha ]. Some were formally involved, others became involved accidentally. All contributed to the narrative of the project to a certain extent, though very few effectively contributed to its making. The architecture historian Peter Blundell-Jones refers how: « with the rise of media coverage of architecture, (…) there is a concomitant rise in public engagement in architecture. But the media, with its emphasis on image and surface, can lead to false participation, turning us into passive consumers and not active doers or makers (…) » (Blundell-Jones, 2005: XV). Peter Bishop and Leslie Williams confirm the recent: « explosion of interest, over the past decade, in ‘public participation’. They expand by stating that ‘Participation is almost universally seen as a ‘good thing’ by democratic national and local governments » (Bishop and Williams, 2012: 138).

Participation is not only assumed to be a ‘good thing’, a means of promoting democracy to the extent that in England, for instance, it has been institutionalised through the ‘Duty to Involve’ that came to force in 2009 requiring local authorities to ‘embed a culture of engagement and empowerment in service delivery and decision making’ (Bishop and Leslie, 2012: 138-9). BIP/ZIP’s programme assumed, as part of the criteria, that all selected projects would have to be participatory. The institutionalisation of participation becomes problematic as the number of participants doesn’t necessarily translate in their level of engagement. Statistically, the musicians who played in the square without an audience, the passers by who sew a seed for the seeds’ bank, the children who glued their drawings onto derelict spaces that needed intervention, the restaurant workers who stole the soil, or those who took home the public benches, added to the number of participants making [ a linha ] a supposedly successful project.

I would then question the role that time plays in this context. Was there time for all the people listed above to actually engage beyond the brief moments during which they were part of the process? Wasn’t their participation somehow superficial, without compromise or commitment, inconsequential and shallow partially because time to engage was scarce? [ a linha ] had a development span of two years, though all funding would have to be spent within the first eight months what would imply that all work developed after the initial eight months would have to be done pro bono. This would involve purely volunteering work what would be difficult to sustain for the remaining one year and four months. For transformation to happen, the work to captivate the local residents and local partners to understand the value and importance of their conscientious engagement and commitment, and to eventually trigger a more proactive attitude towards the built environment from those involved, would have to be incremental, slow and would need to provide tangible evidence that their personal input was contributing to a bigger project, as stated by the Slovenian artist and architect Marjetica Potrč who has long been working on participatory projects across different parts of the globe, and highlights the importance of making something together with the people instead of merely talking or proposing without taking action (Potrč, 2011). Potrč develops the process with the users and builds with the users themselves, making the projects pedagogical tools for resilience. (Potrč, 2016)

Blundell-Jones continues his critique of how media has triggered false participation: « The public thus becomes fixated on a superficial and transient version of architecture, losing sight of the transformative potential of the built environment and the way in which they might become properly engaged in the transformation (…) engaging with all the senses, through time and experience of use. »

Despite having been done in partnership with the Juntas de Freguesia and local schools, [ a linha ] required more time for relationships to grow amongst those involved in the planning and delivery of the project. Only with more time, repetition, consistency of actions, revisiting certain people and spaces, clear communication and open-mindedness could the temporary interventions - the workshops, festival days and the actual street furniture - have surpassed everyone’s expectations and allowed for a change in attitude from the local residents and children. As it were, all interventions became momentary spectacles (Debord, 1994) that, despite their provocative and subversive initial intentions, had very little long-term impact, as despite being taken for granted, not everyone was interested in participating (neither the users, nor the partners). All actions were, to a certain extent, controlled and engagement, when it happened, was not for society’s good but for personal good as seen in the action of the lady who threw the rubbish to the public space, or the collective spirit for individual profit experienced in Santos Populares.

For participatory projects to engage a variety of participants and future users, to challenge the ‘latent form of passivity, apathy from society’ that Henri Lefebvre already described in the 1970s in relation to the way in which cities were being created, time needs to be considered. Without accounting for generous amounts of time, participation becomes no more than the romanticised idea condemned by Miessen. The participants’ role as spatial agents (Schneider, 2013) and active placemakers becomes confined to a good intention without opportunity to materialized it.

2nd story: Time & Event:

There were over 100 people all seating around a long table, designed to resemble a collage of dinning environments, individual or collective, amongst friends or family - a [ table for 100’s ] overviewing Daimyo in Fukuoka. The title of the project had materialised into the luso-niponic banquet I had envisioned.

The temperatures had suddenly dropped and large heaters had to be installed on the rooftop, blankets had to be supplied so that, together with the steam of the cooked food, they would provide enough warmth during the evening. It was my third month in Fukuoka, the last month of a project that initially started in Vauxhall, London, and which was adapted to a whole different context and traveled East, all the way to Japan. [table for 100’s] was an investigation about the connections between Portugal and Japan from a food-related perspective. It was also the debut project for the atelier and the one that, from a logistic point of view, has proved to have been the most successful to date. It wasn’t a self initiated project for a client who didn’t ask for it. It was a wanted gift - bigger than initially imagined - by Konya2023, the hosting gallery.

The residency called for the development of an artwork which would eventually be displayed at their gallery. Instead, I proposed a three month process that would inform the design of the table and which ultimately informed the making of ten other smaller art works that took over the whole building creating a journey that lead towards the table itself. I proposed a process that involved observation of people eating in different places and environments both in Japan and in Portugal. These involved questionnaires about people’s habits around and on the table, historical references about the first arrivals of Portuguese missionaries in Japan: observations about the different habits of the time (16th century) by the missionary Luís Fróis were paralleled to current times. [table for 100’s] also involved workshops with children whose parents were members of a network set up by the gallery; cooking classes to get an in-sight about Japanese cooking; visits to tea, soy and miso museums and factories; experiencing tea ceremonies and eleven dishes’ meals… The whole project was about process - process as a discovery, a learning process shared with those who were invited to be involved, to become participants. All of their input along with my observations materialised on the large table made in just over a day using reclaimed pieces of timber collected from art galleries, university workshops, merchants’ skips.

Preparation time lasted almost three months and then, in one evening, it was all over. Initially, the table was intended not to be placed on a rooftop overlooking the city, but on a square, a street, a dead-end, a neglected public space. Because of time constraints and the bureaucracy involved in the licensing process it was not possible to bring the table to the streets. Instead, the table inhabited a private space overlooking the public realm partially defeating its initial intention and urban and political message. The project was still considered a success, even made it to international press. The table became a token which I could use to promote the atelier’s work. However, the feeling of void prevailed.

After the opening, all the props that had been donated or bought to help creating different atmospheres across the various parts of the table were crammed inside bin liners and immediately disposed, rather than reused. Slowly, the traces of [ table for 100’s ] started to fade away. Some parts of the table were shipped to donors, others reconfigured into displays.

During the opening evening, busy with the cooking and making sure everyone was pleased and comfortable, I couldn’t even enjoy seating around the table that had been the centre of my thinking and of my stay in Japan during the previous months. I wondered if those who went to have a meal around the table even considered all the cultural and political load embedded on that temporary looking giant piece of furniture?

As it got colder, the visitors started to leave. All the steps of the process led to a mere event that lasted no more than a few hours. What stayed beyond the published articles, the website specially created to host all the process, the memories of that evening and my memories of Fukuoka? I do not know.

I cannot trace the impact of my intervention in the city, except for the new human connections that emerged from the process rather than from the event itself. I have no doubt that those who were present at the dinner enjoyed themselves as, after all, everything was slightly exotic, unusual, though strangely familiar. I do doubt the project has left a legacy beyond that of the experience of having a meal together on that long table. The legacy rests solely amongst those who were part of the process beyond the event and contributed to making it happen - Keiko, Yukiko, Yukako, Tsuneo - and all the others who were involved from the moment [ table for 100’s ] was selected to be hosted in Fukuoka. As for the remaining visitors, those that went to the dinner or visited the installation post-opening, [ table for 100’s ] was a mere facilitator for a social gathering for the former, and a large collection of objects for the latter. It was a participated relational object that inhabited the large green rooftop for some weeks, but that soon vanished with the same readiness as its appearance.

This second story focuses on the parallel between a long, thorough, rich, and inclusive process and an ephemeral event, the dinner - the rupture of the process. The two are part of the same project - process and event - though their duration and impact differ posing an interesting question regarding how the first could be perpetuated through the later.

[ table for 100’s ] was a wanted gift. The anthropologist Marcel Mauss states that: « (…) exchanges and contracts take place in the form of presents; in theory these are voluntary, in reality the are given and reciprocated obligatorily » (Mauss, 2002: 3) The project implied a reciprocal act between myself and the gallery’s staff, myself and the participants, and myself and the builders, therefore, in this case, lack of engagement would most likely not be experienced.

This mode of working: engaging all different participants in the process along the various months of my stay, was not familiar to those involved. However, everyone wanted to be part, to help as it was a gift they had asked for.

The process was slow and inclusive, though the dinner resembled Rirkrit Tiravanija’s pad thai project dated from 1990. The Argentinian artist of Thai ascendance challenged the traditional forms of artistic representation and, as a provocation, cooked and served food for exhibition visitors at the Paula Allen Gallery in New York and, in 2007, at the David Zwirner gallery in Chelsea. Tiravanija’s work was later considered to be part of a new art trend coined by the art critic Nicolas Bourriaud as Relational Art. According to Bourriaud, « Relational art is an art that takes as its theoretical horizon the sphere of human interactions and its social context, rather than the assertion of an autonomous and private symbolic space » (Bourriaud, 1998). Relational Art would challenge the contemplative role of art to date, assigning an active role to the audience who would otherwise be passive within the creative process. However, Relational Art works continue to be created by the artists, often not in collaboration with the users/audience, but involving them in a rather superficial manner, as criticised by the art critic Claire Bishop. Bishop opposes to the blur between audience and artist and to the interchangeability of roles between the two, suggesting that the involvement of the audience tends to be rather depthless: « (…) depoliticized celebrations of surface, complicitous with consumer spectacle. (…) A do-it-yourself, microtopian ethos is what Bourriaud perceives to be the core political significance of relational aesthetics (…) »(Bishop, 2012).

[ table for 100’s ] was never designed to be a project where the audience would become part of the intervention, but their input along the process would inform the design of the table itself, and would help choreograph the dinner. The dinner was never the main agenda of the project, the development of the design of the table, and the table as an object that would trigger social interaction, was. The role of the audience was not as active spectators, nor as collaborators or co-designers, but as inspiration for the development of the project so that their habits, thoughts and ideas related to the table would somehow be incorporated in the design, making it theirs, as much as mine, inviting them to re-think some of their rituals and to potentially become makers, agents of change. This direct involvement and experience would oppose to the distanced modes of representation criticized by the Marxist theorist, writer and member of the Situationist International group Guy Debord in his book The Society of the Spectacle. Debord stated that: ‘Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation (…) the obvious degradation of being into having… and from having into appearing’ (Debord, 1994) as a critique of how society was changing in the late 1960s and how it was being exploited under advanced capitalism.

Debord's critique remains relevant today when social relations are frequently reduced to ephemeral interaction. Tailored representations of the self in social media are presented as real. The thrill of the event and the immediate satisfaction and pleasure it generates, surpasses any interest or need for a long term involvement or commitment in gaining a more in-depth knowledge or to push any political statement further making something ephemeral into a change of policy.

The time constraints did not allow for a long-term conversation to be established between myself and those who were involved. Yet, it’s boldness and unfamiliarity allowed for it to be retained in people’s memory, even if it did not generate any long-term social or spatial transformation. More time would be required for such to have happened.

3rd story: Time & Legacy:

2016 was about to start when I received an email from Paula in response to the atelier’s newsletter informing about the progress of the current projects in Norway and Beja. Paula is one of the nursery teachers from PRODAC’s Santa Casa, with whom I worked in the project [ jogos de rua] in 2012-13. The project didn’t end in joy, but with a slightly bitter taste. Most projects do despite no one ever mentioning. I had not been in touch with PRODAC’s school for a couple of years. Paula’s email came as a surprise. It was succinct, though enough to clarify the uncertainties I had regarding the value and nature of the work I had been believing in for the last decade having repeatedly faced unexpected obstacles and frustrations dissonant from the supposedly participatory nature of the projects.

I was trapped in my own disbelief that work of this nature was worth doing, but Paula’s words restored a level of hope:

« Estive a navegar pelos teus projetos e deixei-me embarcar numa história bem contada.

Ver o mundo pelos teus sentidos é desassossegante, desperta-nos memórias e vontade de experienciar momentos de descoberta, desprovidos de qualquer preconceito.

O desafio de aprender a olhar e viver em harmonia a vida, o outro, o tempo e o espaço, é contagiante.

Obrigada pela generosidade da tua partilha. »

« I was navigating through your projects and allowed myself to embark on a well told story.

Seeing the world through your senses triggers a feeling of restlessness, awakening memories and the will to experience moments of discovery, deprived of any prejudices.

The challenge of learning to look and observe in harmony with life, the other, time and space is contagious.

Thank you for your generosity and for sharing. »

[ jogos de rua ] as all the projects we have done so far, involved a rich and diverse thinking and making process where we worked with different partners in a more or less involved way, depending on their interest in committing to the project. It resulted in mere temporary interventions, with no other legacy beyond the memory of the experiences generated through the involvement in the projects. The focus was less on the result and always more on the process. We worked with PRODAC’s children over some months. They drew, modelled, mimed… what was followed by six weeks of collecting, choosing, sawing, hammering, nailing, assembling, painting and testing before the eight mobile play and games units were finally ready to be moved from our beautiful improvised workshop in Alfama to PRODAC.

In February 2013, a lively parade where all eight mobile play modules built based on the input from the children and parents involved, took over the streets of the neighbourhood. Together, children, parents, friends, teachers, other school staff, and us (atelier), wheeled the modules across PRODAC at the rhythm of the Leo’s flute played along our journey. The glow in the children’s eyes, the joy and surprise in seeing those pieces they helped creating travelling across their neighbourhood, awakening their grandparents with the surprise, made up for all the difficulties, misunderstandings, obstacles, frustrations and anxieties felt along such a short, though intense journey. For that one moment, [ jogos de rua ] was able to awake the otherwise dormant PRODAC, a moment that was perpetuated over the months during which the modules were used in the school.

Similarly to [ a linha ], [ jogos de rua ] was one of the selected projects to be funded by the BIP/ZIP programme in 2012. Despite it’s supposedly two years sustainability period, all the funding had to be spent within the first nine months of the project’s development. That implied a very short period of time for the atelier to develop a close relationship with the local residents. Once again, we worked with the local school not only due the pedagogical value of the project itself, but also with the aim of reaching the children’s families and friends in order to have an impact beyond the activities developed for the workshops during the process. This should allow for the project’s continuation, for it’s sustainability to happen without the need for extra funding. All projects intended to trigger the desire for one to become resilient, to seek opportunities and resources wherever possible. For such to happen though, time would be crucial.

By the end of the academic year, the Library module was the only one the school managed to keep. Some of the other modules became too worn out from the children’s use and were disposed, others were slightly broken and after having been fixed a couple of times were equally disposed. Time was not long enough to change mind-sets, to incite a more resourceful spirit amongst the school’s staff. However, the project triggered new smaller projects, branches of the original idea even if no physical legacy remained to testify the presence of [ jogos de rua ] in PRODAC.

This last story closes the circle of the essay drawing the conclusions to the shared reflections. Throughout the five short stories that described different approaches to time in the making of participatory projects, one could recurrently observe that the importance of time tends to be underestimated. Despite the value of the ephemeral, counteracting the usual ‘dream of permanence’ as stated by Bishop and Williams triggered by a sense of security, comfort and certainty, a slow approach to time revealed to be crucial for any of the projects to have a long-term impact beyond the fugacity of the event, to leave a material or immaterial legacy.

Bishop and Williams refer to some of the positive aspects of temporary urban interventions as fringe activities that are vital for the urban economy and how they contribute to the evolution of urban fabrics (Bishop and Williams: 2012, 17-19). Temporality can, by itself, be understood differently depending on the different timeframes being considered, allotment gardens differing from one day workshop or event. The later tend to limit their impact to the moment whilst the allotment gardens, for example, despite representing a temporary use of land, require years for the plants to grow and influence people’s behaviour and spatial perception.

[ jogos de rua ] was designed to encompass three different temporalities: the ephemeral - the parade with the mobile play modules; the temporary - the inhabitation of the schools’ playground with the modules; and the legacy - the change of attitude towards the built environment having developed a more resilient and resourceful approach to ones’ surroundings. For this last temporality - the legacy - more time on the two previous stages would have been required.

[ jogos de rua ] slowly faded not only from the children’s memory, but also from the urban contexts leaving nothing but faint imprints of the momentary actions initiated by the atelier. Without a legacy that remains beyond materiality, these urban interventions become no more than soft transient punches that do not have the strength to break through the system or to become powerful enough for spatial and social transformation to happen.

Conclusions

The three stories are a mere sample of episodes that have occurred in the various participatory projects the atelier has undertaken over the past years. All, with no exception to date, have lacked longer periods of time during the initial engagement processes in order to create a shift from being solely the atelier’s project that fade once we leave the interventions’ territory, to becoming collective and collaborative processes and to have a longer term transformative effect triggered by the initial political intention. In order for that to happen, time should be the starting point of any collaborative conversation. Commitment and collaboration require time to materialize into something that is effectively a product of a joint effort. As the art and architecture practice muf would define: « We painfully discovered that collaboration is not about different disciplines and personalities climbing into a blender and producing a consensus. Rather, it has to be the deliberate creation of a sufficiently generous atmosphere to make room for the different disciplines and personalities, both ours and those of consultants, friends and lovers... (...) being in one room, dialogues and eavesdropping inform projects. (…) One unconscious collaboration has been the drawing on and refining of earlier projects and research. This shared working - displaced by a number of years, and by sites hundreds of miles apart, with radically different briefs - leads to templates being handed from one member of the studio to another. Perhaps it’s about getting older, staying home more and drawing on what’s already there. » (muf, 2001: 10)

The idea of ‘staying home more and drawing on what’s already there’ can be understood as the allowance for enough time on site in order to be able to understand its topography and demographics: its inhabitants and their habits, rituals and interests.

Both [ a linha ] and [ jogos de rua ] required more time for the users to engage, more time for the construction process to have become a collective act, and more time to inhabit, expand and transform the structures that we created so that those would have lead to variations of the existing ones, new modes of playing and inhabiting the city, new social interactions amongst those who despite being so near each other remain apart. Then, temporality would make way for an immaterial permanence.

[ table for 100’s ] confirms that despite the engagement of the participants and the success of the event, a third moment would be needed for the project to have been truly successful, the coda. Coda, is a musical term that represents a passage at the end of a musical composition bringing the piece to a satisfactory close. Once the dinner ended, [ table for 100’s ] was gradually dismantled. The experience and memories of the meal might have prevailed, but the whole duration of the project was insufficient to reach the coda, therefore the initial intention subjacent to the project never materialized. The table’s role as an activator of underused or neglected public spaces could not occur as there was not enough time to approach the local authorities and ask permission to occupy a derelict or underused space and Konya was not willing to do it without permission.

These projects have illustrated the intrinsic connection that exists between time and participation, the later dependant on the former to have a long term impact beyond the ephemeral urban intervention allowing for tactics to surpass the boundaries of technocratic strategies that limit one’s role as an active maker of our cities.

REFERENCES

Bishop, C. (2012), Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London: Verso. [ Links ]

Bishop, P., Williams, L. (2012), The Temporary City, London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Blundell Jones, P., Petrescu, D., Till, J. (Eds.) (2005), Architecture and Participation, London: Spon Press. [ Links ]

Bourriaud, N. (1998), “Relational Aesthetics”, in C. Bishop (Ed.), Participation, London: Whitechapel Gallery. [ Links ]

Debord, G. (1994), The Society of the Spectacle, New York: Zone Books. [ Links ]

Harvey, D. (2012), Rebel Cities : From the right to the city to the urban revolution, New York: Verso. [ Links ]

Lefebvre, H. (2003), The Urban Revolution, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Mauss, M. (2002), The Gift, London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Muf (2001), This is what we do, a muf manual, London: ellipsis. [ Links ]

Potrč, M. (2011) ‘Interview with Marjetica Potrč’, Skor Foundation, available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B2M0qxHcYfc . [ Links ]

Potrč, M. (2016), On-Site Projects, available at: https://www.potrc.org/project2.htm . [ Links ]

Roseta, H. (2013), “Pequeno Programa, Grande Lição”, in Dentro de Ti Ò Cidade, Energia BipZip, Lisbon: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. [ Links ]

Schneider, T (2013), “The paradox of social architectures”, in K. Cupers (Ed.) (2013) Use matters: an alternative history of architecture, New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Recebido: 03-01-2017; Aceite: 07-06-2017.

NOTES

[2] My translation from the original extract in Portuguese: “O conceito BIP-ZIP – Bairros e Zonas de Intervenção Prioritária nasceu da consciência que tínhamos, findo o processo de erradicação das barracas em Lisboa, de não terem acabado as desigualdades urbanas na cidade. Fomos à procura delas e encontrámos 67 territórios – bairros, pequenas zonas, às vezes apenas uma rua – em que as dificuldades económicas e sociais das pessoas e os problemas urbanísticos e ambientais do edificado exigiam uma resposta urgente.”