Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

CIDADES, Comunidades e Territórios

versão On-line ISSN 2182-3030

CIDADES no.35 Lisboa dez. 2017

https://doi.org/10.15847/citiescommunitiesterritories.dec2017.035.art02

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Post-Graffiti in Lisbon: On spatial localization and market absorption

Post-Graffiti em Lisboa: sobre localização espacial e absorção de mercado

Rohit ReviI

[I]Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Gandhinagar, India. e-mail: rohit.revi@iitgn.ac.in.

ABSTRACT

Graffiti-making has been historically well located within the politics of territoriality/ transgression, deindustrialization/ decline, appropriation/ affirmation and other such inter-related frameworks. Such historicizations exist in parallel to a history of institutionalization of graffiti-making, leading up to the first emergence of the phrase post-graffiti in the discourse. The post-graffiti has alternatively and independently also been used to describe an empirically observed shift in graffiti-making practices; from the typographical to the iconographical. In this context, the operationalization of a set of urban intervention policies by the Lisbon City Council provide an interesting inroad into the processes that underlie the market absorption of graffiti. Through a field analysis of street art in Lisbon as well as an examination of the intervention policy and its consequences, this paper presents that the intervention policies and associated public rhetoric manufactured a binary of order-disorder within the practices of graffiti-making, enabling graffiti and graffiti-making practices in Lisbon to be spatially localized. Such spatial localization, in turn, facilitated market activities surrounding graffiti. For the graffiti and the graffiti-makers, state/administrative sanction and the emergence of market activities meant heightened security, safety and a greater audience field – conditions that made iconographical aesthetics a virtue and a greater necessity. Thus, the post-graffiti shift in aesthetics has to be understood within the context of institutionalization of street art enabled by urban interventions and contemporary capitalism.

Keywords: post-graffiti; street art; Lisbon; transgression; market absorption.

Introduction

The walls of the city of Lisbon have been inscribed and re-inscribed many times. Broad walls between narrow alleys are sprayed upon, night after night, by many. In the tunnels of Alcântara, the desolate buildings by the river at Jardim do Tabaco and the walls of Amoreiras, artists of global relevance converse with their audiences. Similarly sprayed upon are the inner alleys of Alfama, the shutters on the shops of Rua de Santa Marta and the inner walls of the metro tunnels, perhaps by artists lesser known. The buildings and the walls of the city are known to spray cans all too well. Recently, however, they have been familiar to tourists with cameras and maps, as well (Daniel, 2016).

Traditionally, the politics of graffiti has been well located within the politics of marginality, territoriality and transgression. Inscriptions on the walls of a city were looked at as acts of geographical deviations that render visible the every-day relationships between ideology and space (Cresswell, 1996). To spray a wall was understood not merely as an act of colouring, but an act of disclosing details about the ownership and propriety of what is considered to be public. In this sense, graffiti was considered to be a problem because it challenged the rights to ownership of property and thus, the organization of urban space (Iveson, 2002). To Cresswell (1996: 58) too, the criminality of inscription lied precisely in its visibility as a “transgression of official appearances”. Indicating the politics of transgression that graffiti operated within in the city of New York, he observes that graffiti was looked from a “discourse of disorder”, characterized by a public language that drew associations with ‘dirt', ‘madness' and ‘disease' (38-45). Mirzoeff (1995: 147), observes how the graffiti in New York was seen as an “assault on society” by the mainstream media, inviting ethical questions on the condition of modern society. An indication of the worth of the artist and the value of the art were measured by the “conspicuous” and “daring” nature of spaces that were inscribed by the artist. The more visible and difficult to penetrate a space was, the more dangerous and thereby valuable the art. Cresswell (1996: 147) argues that the threat posed by graffiti was not particularly to the urban space itself, but the image of it. That is to say, graffiti presented an ‘illusion of disorder' in the urban landscape, by conflating the notions of and boundaries between private and public space. There were thorough and obvious spatial and thus ideological dimensions to this transgression. The public panic that surrounded inscriptions might seem to be of preposterous proportions in hindsight, but the significance of the new art form to the world it was born into must not be overlooked. Like the public, many commentators too viewed the emergence of graffiti as a huge and irreversible event. So much so, Gablik (1984: 103-113) for instance, elevated the rise of graffiti to be a mark of ‘the end to modernist self-assurance'. To the same effect, Mirzoeff (1995, 148) observes that street art performances threatened the hegemony of the modernist art project, a hegemony that was structured in Europe after the Second World War. This was made possible by the challenging of modernist values of contemplation and reflection that underlay art production and their subsequent replacement with the uncertainty and dramatism in graffiti inscriptions. The “myth of the Romantic artist” and the steady emotional recollection in tranquility that was supposed to be crucial was unfamiliar to the people with spray cans who worked at night and in fear of the law and the police. The absence of legal safety and security was central to the inscription. Mirzoeff in his polemic, identifies that for the privileged, while the totem of modernism, the “evidence of the power of Imagination”, was missing in graffiti, the symptoms of marginalization “illiteracy and primitivism” were very visible. The incompatibility of this art with the gallery was an uneasy affair for many critics, he argues.

It is apparent that the transgression that this new art made possible was clearly disruptive; not only in the landscapes of the owned urban properties, but also in the core hegemonic values of its times.

What then, to come back to the flaneurs with their cameras and their city maps, is the origin of the calm and the comfort with which street art is inscribed, observed and transacted in the streets of Lisbon? It is at the face of this question that this essay attempts to understand how the possibility of commercially valuable street-art through street art tourism was explored and the possibilities for real-estate valuation of urban inscriptions were opened up, through the urban intervention policy by the City Council. The case of Lisbon is important both for the contemporary discourse on post-graffiti, and the understanding of its relation to the processes enabling the market absorption of transgression in late capitalism.

The fieldwork that resulted in this work spanned across two months in the city of Lisbon, and was carried out as a part of a postgraduate internship, with support from ISCTE-IUL, Lisbon. A study of the existing literature on the politics of graffiti and post-graffiti was carried out, following a study of the intervention policies by the Lisbon City Council. This was complemented with regular visits to various quarters of the city, in order to carry out a content analysis of the visible forms of graffiti and their spatial specifities, as well as a study of the locations that were popular with street-art tourists. The author would like to thank everyone who supported and co-operated with this study, without naming anyone specifically.

This paper is divided into 4 sections; on post-graffiti, on the intervention by the Lisbon City Council, on the relation between market and the intervention, and on the relation between market and the post-graffiti.

A. Note on the Post-Graffiti

There is a legitimate and parallel history of institutionalization of graffiti that runs alongside the history of transgressions. The historicizations of the former kind have been considerably less in number, in comparison to the latter. The institutional history of graffiti is, however, an important history that has been characterized by an incrementally frequent series of events that have, apparently, been in the direction of either the museumification of graffiti or the graffitization of museums/galleries. That is to say, either public spaces with street art on them have been converted into public galleries, or galleries and museums have begun featuring graffiti artifacts on display. In no way is this a singular history of graffiti, but it is a distinct and singular thread in the complex history of graffiti in the modern times.

Mirzoeff (1996, 149) observes, within the very same context of New York, that parallel to the story of disruption, graffiti was also subjected to processes of institutionally driven commodification in the art world. Kimvall (2014) further attempts to elaborately locate the institutional history of graffiti. It is important to acknowledge and briefly present this history, in order to arrive at the post-graffiti. The first street-art exhibition that is recorded was in Art Today by Edward Lucie-Smith, in September, 1973, in Razor Gallery, curated by Hugo Martinez. Subsequently, Martinez founded United Graffiti Artists (UGA), the first organization for graffiti inscription and exhibition. In parallel, around the same time, alleging UGA of being closed and elitist, the Nation of Graffiti Artists (NoGA) was formed by a figure by the name of Jack Pelsinger, a group that advocated openness to artists. In the following years, there was a rise in the number of artist conglomerates and associate exhibitions (primarily non-profit), Kimvall notes. This rise, through the 1980s saw the emergence of frequent exhibitions, often with a definitive commercial agenda. With New York as a financial capital, the art establishment and the press began to take particular notice upon inscription (Haden-Smith, 2007). The for-profit gallery spaces began to be graffitized. There was a dual process, he further posits, that potentially functioned beneath the formation and operation of these conglomerates. Through formation of such quasi-unions, the presence of graffiti within the contemporary art scene was articulated and the audience widened, and simultaneously, the writers were able to identify themselves as artists in the more conventional sense. The claim of widening of the audience field through institutionalization will be of particular importance to the scope of this paper. In the more contemporary times, the emergence of street art galleries, with values of pride and prestige associated with display there, such as Art in The Streets at MoCA in Los Angeles, and the high-profile auctioning of popular works of transgression, are arguably parts of the same history.

There are two distinct contexts in which the post-graffiti was rendered visible, and this delineation has been made by Dickens (2009). The initial emergence of the phrase through the prescribed ‘death of the graffiti' is tied up with the institutional history of street art and the cultural history of New York. He observes that one of the ways in which the writers responded to the “intolerance on the streets” towards graffiti, was by engaging with gallery shows and producing works on canvasses that could be auctioned or sold. ‘Writers' were now ‘artists' and they could expect fame and/or financial rewards through such a re-channeling. The emergence of the post-graffiti in the discourse for the first time is at this point, as observed by Dickens through Cresswell (1992, 1996), Austin (2002) and Hoban (2004). The displacement of inscriptions away from open urban spaces to galleries seemed to be followed by the newly opened possibilities of monetization (Dickens 2009). The exhibition titled the Post-Graffiti Show curated by Dolores Neumann at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York City, in December 1983, was an important point in the institutional history of Graffiti. The show sold off major works by train bombers on canvases (Hoban, 2004: 37-38). For some observers, the emergence of the post-graffiti was a compromise on the disruptive capabilities that 'authentic' graffiti of the previous times supposedly possessed. Cresswell (1996, 51), for instance, minces no words when he speaks of Neumann's show as “the death of real graffiti”. It is of course unnecessary and quite useless at this point to embark on locating the authenticity of different kinds of graffiti. However, the idea that post-graffiti is a significant shift of some kind away from graffiti, by virtue of institutionalization, is of importance.

Dickens (2009: 74) notes the re-emergence, for a second time, of post-graffiti as a term in the language of “international art texts, films, exhibitions and conferences”, and notes a “coherent theme” that connects its usage across literature. This theme is characterized by a qualitative shift; away from the more ‘classic' forms inscriptions and towards a “discernable new aesthetic practice”. The post-graffiti in this sense is not about the shift away from streets and into the canvases, but an aesthetic one. This involves a popular replacement of ‘tags' with ‘street logos', an aesthetic shift away from the typographical to the iconographical (Manco, 2004). Dickens (2009, 77) suggests that a post-graffiti movement “actively seeks to produce a more universal, democratic aesthetic than the cryptic and prolific language of tagging, by reaching out to a far broader array of urban publics through an emotive symbolic language that predates words”. On a different axis, there are visible influences of technology and digital connectivity in the way artifacts are communicated and spread as well (Ganz, 2004: 9). Dickens (2009: 92) also identifies the existence of the linkages between the commercial processes of the contemporary times and the post-graffiti movement. Reinecke (2007) in fact, defines ‘post-graffiti' as “a subculture between art and commerce”. Miniaturized memorabilia and other forms of re-production of street art through the commercial processes of commodification, is also an empirical reality that coexists with the aesthetic shift away from the typographical and towards the iconographical. In the light of these characters, it is important that any post-graffiti movement be analyzed not only in close relation to the nature of the audience and the scope of the audience field, but also the changes within the socioeconomic conditions, in connection to the role of the market, that have taken place.

B. Intervention by Lisbon City Council

It is important to come back to the institutional history of graffiti, in order to go back into the politics of the post-graffiti. It is necessary to fore-ground the institutional history, with all its consequences to locate the consequences of the intervention by Lisbon City Council that is of importance to the scope of this paper. In the context of the conflict that institutionalization brings to an art whose essence some would argue is anti-institutional, Austin (2002: 187) describes “an embittering clash between two very different prestige systems, one institutionalized in the commercial art galleries and the other in the train yards”. Cresswell (1996, 51) demonstrates that the interests shown by the Manhattan Galleries in the 1980s towards graffiti, was in association with a process of cooption that was designed to subject graffiti inscription to commodification and transformation.

“Graffiti in the gallery is graffiti in its ‘proper place'. It is no longer a tactic of the marginalized but part of the strategy of the establishment, conforming to the codes of the ‘proper place'” (Cresswell, 1996: 51)

The post-graffiti movements negotiated with the ‘proper place'. On one side there existed “the street artists, print houses and specialist galleries” and on the other existed the collectors and the fans of the art (Dickens, 2009: 395). Between these sides, there emerged new transactional relationships that Dickens introduces as relationships between art and commerce. In this particular context, facilitation of commercialization through institutionalization is an important thesis, and it is of importance to look at the possible mechanisms that can enable this causation. The case of state intervention in Lisbon can potentially clarify this.

Graffiti inscriptions in Lisbon proliferated through the 90s and, by the mid-2000s, the art had significant influences on social relations within the city, leading to the rise of what Costa (2013) refers to as ‘use conflicts'. ‘Use conflicts' are conflicts that emerge between the various and diverse stakeholders of the city space, such as the residents, the passerby, the loiterer, the artist, the municipality and so on. Owing to a growing number and intensity of ‘use conflicts' in various areas of the city, especially the areas signifying the various youth cultures (such as Bairro Alto, a popular locale designated almost completely for recreational nightlife), arising from artists inscribing walls with contents of their choice and in bulk, the City Council attempted to mediate through an intervention (Costa and Lopez, 2015). This started off as a hygiene drive in October 2008, a decision that Costa and Lopez identify as the beginning of an alternative urban intervention policy. The set of measures were taken by the City Council independently, but they were thematically connected, and oriented towards the same end. The initial program was dedicated to cleaning up the main streets, the most visible areas and the titular agenda was “changing the image of the quarter”.

Two seemingly contradictory statements by the then newly elected president of the Lisbon City Council, António Costa in Público/Agência Lusa, dated October 2009, quoted by the authors, are of interest to us here. The proclamation was that “those who paint the city have to understand that crime doesn't compensate”, referring to graffiti as a crime and incriminating artists in a sweeping remark. In this particular direction, the following policies were implemented (Costa and Lopes, 2015):

• policing in the quarter was increased,

• study for the installation of surveillance cameras,

• a 30% increase on public lighting,

• a new system of sanitation,

• restriction of the schedule of nightlife

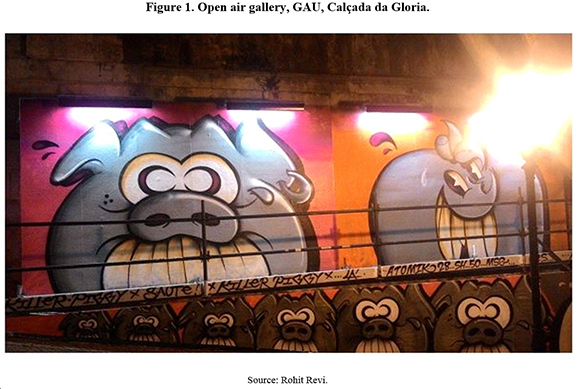

It is also of significant interest that it was at this very point that the City Council created the Urban Art Gallery one of the novel initiatives at the time, known to the Portuguese speakers as GAU-Galeria de Arte Urbana, under the jurisdiction of the Department of Cultural Heritage. Among the many other duties, GAU was designated with the duty of managing public spaces, some “outdoors” that were designated for graffiti, near Bairro Alto, in Calçada da Gloria. In reference to GAU, in the same source, was the contradictory quote by António Costa, that said GAU is a space for “the good art that comes there to be created”. This indicates, clearly, an endorsement towards a particular kind of graffiti. Inscriptions were relevant as long as they were ‘good', while anything short of this standard being ‘criminal'. At construction here, visible to us through this specific contradiction, is a binary of order and disorder in the perception and practice of graffiti inscription. It is not intended in this paper to analyze what the order/disorder meant for the content of art in the spaces where they are produced. In the following section, I examine the consequences of this intervention and relate them to the present condition of market activities surrounding graffiti in Lisbon.

Order/Disorder

It is viable to go back to Cresswell (1996b: 37) to re-trace a historical source of this binary. Cresswell compares two paradoxical attitudes towards the practice as well – “the frantic responses to graffiti on the street that sought to portray it as deviant” and “the enthusiastic acceptance of it as art by the SoHo art community”. Cresswell responds to this paradox. “The question of whose world is being written over – the crucial where of appropriateness – is never a purely aesthetic judgement. The question of geographical hegemony – the taken-for-granted moral order – inevitably imposes itself on the politics of aesthetic and moral evaluation.” (Cresswell 1996b: 46). “At the same time as graffiti was painted as a wild anarchic threat to society by one dominant group (the ‘authorities'), it was taken off the streets and placed in galleries by another dominant group (official culture)” (Cresswell 1996a: 50).

Cresswell identifies the mutual reinforcement between the art establishment and the state, in the attempts to vacate the streets of the art and instate them into their ‘proper places' – the galleries. The ordered graffiti in the galleries were set up in opposition to the “wild anarchic threat” on the streets. The sources of mediation, the “dominant groups” as Cresswell refers to them, are not different in Lisbon. The state, the market and the art establishment converges in the authority of the City Council, as the Council set up both the retributive measures towards disordered graffiti as well as the new galleries for the ordered ones – the locus of control in the mediation of inscription was centralized with the state. City Council also took a detour from moving towards the popular system of the gallery. Instead, they allocated space in the various quarters of the City that functioned as sanctioned the commons for inscription by actors. Particular spatial correlates were framed for the graffiti that was ordered, juxtaposed with the aforementioned stricter retributions for the disordered ones (Costa and Lopes, 2015). In effect, this enabled the possibility of spatial localization of graffiti in the city.

The initiatives of GAU seem to be comfortable with the post-graffiti movement and the relationship between art and commerce it entailed. It is commonplace to witness artifacts on the streets commissioned by the council that are characteristic of the post graffiti. The gallery space appeals to audiences that are uninitiated with typographic work, through lustrous and complex iconographic works. Although there are visible typographic works on the walls of Lisbon, these are mostly the illegal and unsanctioned work. The state sanctioned territories house works that exhibit visible post-graffiti tendencies. The project of Reciclar o olhar (“recycling the look”), for example, was a very popular initiative by the GAU, where the general public was called forth to paint some of the roadside bins that collect glass bottles for recycling. Tagged as a democratic project, this produced a significant artistic engagement between amateurs, children, the elderly, the established artists and the streets of Lisbon. Costa and Lopes also draw our attention towards some of the other projects that GAU took up.

However, these included: implementing social inclusion and educational oriented projects (e.g. in middle class neighborhoods – like Telheiras – or in more deprived communities – e.g. Flamenga); legalizing other new spots for art intervention; organizing regular urban art competitions; developing organized tours to urban art circuits (e.g. Go art program) and other media oriented activities; collaborating with other city council departments (e.g. licensing urban art activities or organizing specific works, such as a wall intervention on a new municipal parking lot); and even researching, documenting and publishing work. (Costa and Lopes, 2015)

It is evident through cursory analysis of the post-graffiti activities of the GAU that this was the beginning of the state taking control of performance, maintenance and jurisdiction over the inscriptions. From commissioning desolate buildings for art projects to public outreach programs, street art was designated to be operated by the state, in heavily designated and localized spaces, within the framework made possible by the order/disorder binary. The operation of such centralized control has significant relations for the market.

C. Intervention and the Market

As discussed in the previous sections, commercialization of graffiti has been a specter that has stayed with the art since its early proliferation. Traditional activities of inscription walked “a fine line between the recognition of its merits and commercial appropriation” (Dickens, 66). It is difficult in recent times to speak of the commercial axis of street art as being defined by its presence in or absence from the pre-existing capitalist system (101). According to Dickens, the commercial quality of post-graffiti should not be crudely reduced to the binaries of inside/outside market. The commercial quality is characterized by newer modes of connections between consumers and the art scene. He notes the popularity of commodities such as “screen-printed reproductions of street art, coffee-table art books, collectable toy figures and customized items such as trainers and spray cans” (102-103). The case of Lisbon seems to one such newer mode. The operation of the institutional intervention in Lisbon enabled a stronger association between consumers and art; this time not through marketable commodities, but through marketable public spaces and real estate management. Reinvigoration of desolate buildings and bare walls through urban intervention by the council opened up possibilities of having “indirect multiplication effects on real estate, art market and tourism” and the symbolic value generated through artistic interventions gets transferred into real estate value to the benefit of private real estate owners, revealing the process of gentrification at play (Costa and Lopes, 2015).

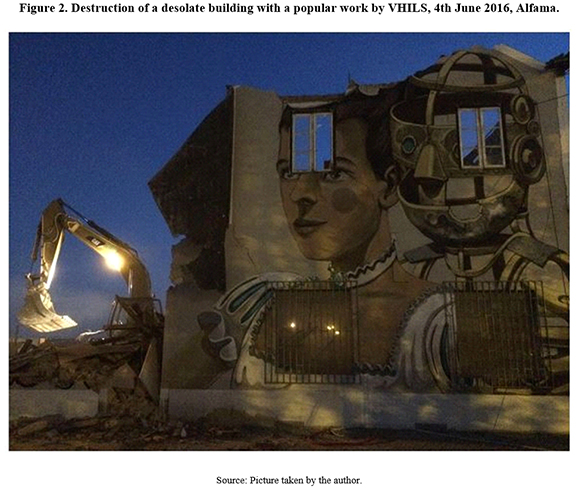

For example, on 4th June 2016, a desolate building along the bank of the river at Alfama that housed an intricate work of graffiti by the popular artist VHILS, was being brought down by state. A few people huddled around the building observing it being torn down by an excavator. When the supervising officer was asked why this was being done, he responded saying it was for “renovation of the river front”, a common event in the city. Newer economic activities seem to necessitate a destruction of the artwork commissioned upon desolate infrastructure, implying that the commissioning of art itself is an economic activity that renders the space useful until a newer project is commissioned.

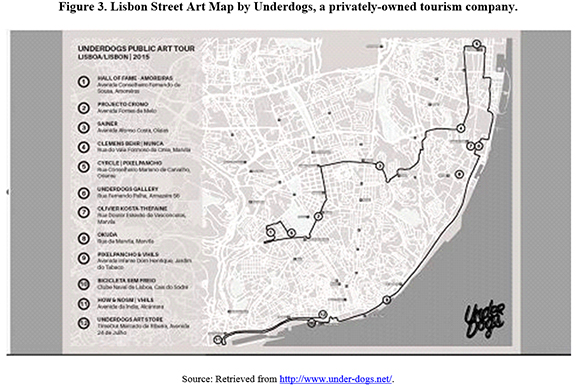

There are simultaneous processes that are at play here – the controlled artistic intervention in the public space can now generate economic value through a private consumption of the public spaces (via street art tourism), a reinvigoration of real estate value for public/private spaces. In the case of Lisbon, the intervention into the commons, the cause for the absorption of the art-space by the market, was made possible because it is now the state itself that has taken centralized control, in place of private agents such as the art establishment or the market. Further, the spatial correlates of art being defined, enables a fixed and easily available knowledge of the kind of art and the location at which it exists. It becomes possible to map the exact geographical and spatial locations of art in the city. This would not have been possible without the City Council actions.

Street art tours could now confidently arm the tourists with maps that locate the artifacts in the city. With the spatial localization of the artifacts and the commissioning of actors to create them in the first place, the uncertainty and illegality that entailed traditional inscriptions as observed by Mirzoeff (1995), which were the core values that politically challenged the established norms of the art establishment, lose significance. In their place, safety and security emerge as characters of the graffiti.

The urban intervention, it has to be observed here, blurred the divide between state interest and market interest. The intervention facilitated a ‘democratic' framework to resolve the use-conflict while policing the operation of street artists, and simultaneously generate economic value for graffiti as well as public and desolate spaces. Visible here is an increased alignment between the interests of the market, the interests of the state and as the next section presents, interests of a few artists and art consumers.

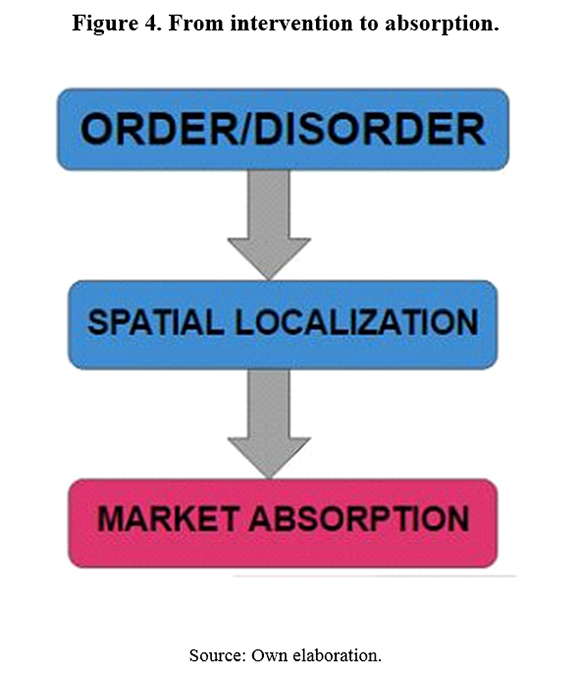

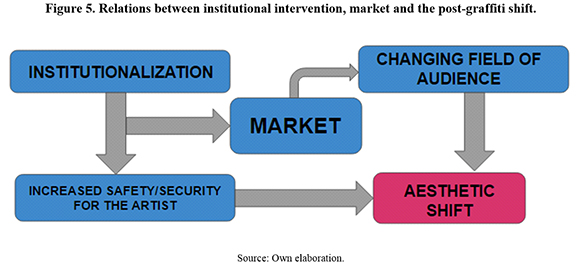

There is a fairly evident chain of consequences that is visible, that lead us to market absorption from state intervention. The order/disorder binary that was set up through the intervention enabled a spatial localization of graffiti that made market activities centered on it possible.

These artistic interventions by the City Council exhibited a thrust towards post-graffiti tendencies, and thus we must also examine the relations between the post-graffiti and the market.

D. The Market and the Post-Graffiti

As described in the Introduction, there were numerous factors influencing the production and reception of the traditional acts of graffiti inscription. Criminality was central to this. The spontaneity, uncertainty and nocturnal nature of the art, the obscure identities of the writer and their tags, were all intrinsically tied to the fact that the art was illegal and the writer a criminal (Cresswell, 1996; Mirzoeff, 1995; Lachmann, 1998). The audience field, the domain of people engaging meaningfully with the artifacts, were limited to the artists and the relatively few who were initiated with the form of the obscure typography (Manco, 2004) (Dickens, 2009). These factors heavily diminished the possibilities of market domination of street art. From the institutional history in Section A, it is visible that the monetization of street art was mostly limited to the exhibitions in galleries and film-making pertaining to the art scene.

In Lisbon, the problem of safety of the writer and the security of the work, factors that hinder marketability of the work, effectively underwent resolution through the Council's intervention. As mentioned above, through the sanctioning of space, commissioning of artists and proposal of projects, by a centralized state control, the promise of safety, security and legality was made for the ordered graffiti. Costa and Lopes (2015) indicate that the artists underwent a negotiation between two kinds of reputations: the one made available through larger visibility and popularity that the state offers and the one that exists within the art community that held transgression, disruption and violation as core virtues of street art. Artists had to negotiate between the order and disorder and make their choice. In order to engage meaningfully with the opportunity offered by the state, it was important to also engage with the larger audience field of tourists and the uninitiated observers. This necessitated a shift in the mode of inscription.

As mentioned in Section A, the post-graffiti brought such an aesthetic shift away from the typographical to the iconographical. The attempt to produce “a more universal, democratic aesthetic than the cryptic and prolific language” of tags and words is very much at the heart of the post-graffiti movement (Dickens, 2009). To converse with the uninitiated observer iconographical visual appeal becomes important. In order to engage with the urban space from within the conditions of the state-market liaison, and simultaneously communicate democratically, the aesthetic shift of the post-graffiti was necessary.

It is important to understand here that the two seemingly separate ways in which post-graffiti emerges in the discourse, the aesthetic shift to the iconographical and the institutionally meted out ‘death of the graffiti', as identified by Dickens (2009), are not disparate or discreet. Both of them articulate the same symptoms of market absorption done through institutional control and popular democratization.

Concluding Remark

In this article, I attempted to locate the intervention policy of Lisbon City Council within the institutional history of graffiti and the post-graffiti movement, in order to be able to explicate the processes that under-laid its market absorption. I have argued that the City Council, through a manufacture of a binary of order/disorder in the inscription of street art, attempted to enforce a spatial localization of street artifacts in the city of Lisbon and complemented this localization with particular sorts of artistic interventions. The localized and controlled artistic interventions made it possible for the neoliberal state-market liaison to generate economic values in the public resources to the benefit of the real estate and the tourism industry.

In this regard, there is a visible change in the political relations between street art and the commons. As we have mentioned, the traditional politics of graffiti had been conventionally framed in terms of resistance towards the tragedy of commons. But this has undergone a considerable transformation with the emergence of the post-graffiti. By historicizing post-graffiti within the multiple processes of institutionalization of street art, widening of audience field and growth of complementary, systematic interventions within a state-market nexus (such as the case in Lisbon), we are able to bring forth the compatibility of contemporary capitalism and the post graffiti condition.

It is of importance that this process of market action was complemented by the aesthetic shift of the post-graffiti movement towards the iconographical, through its production of artifacts accessible to the tourists and the uninitiated audiences, with aesthetic complexity and visual appeal as core virtues.

Referências

Austin J. (2002) Taking the Train: How Graffiti Art Became an Urban Crisis in New York City , New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Costa, P. (2013) “Bairro Alto revisited: reputation and symbolic assets as drivers for sustainable innovation in the city”, DINAMIA-CET Working Paper 2013/14. [ Links ]

Costa, P., Lopes, R. (2015) “Is street art institutionalizable? Challenges to an alternative urban policy in Lisbon”, Métropoles 17. [ Links ]

Cresswell, T. (1996) In place-out of place: geography, ideology, and transgression, University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Daniel, D. (2016) “Graffiti was just the beginning: On the streets of Lisbon, the energized city becomes the canvas”, National Post. Available at http://news.nationalpost.com/life/travel/graffiti-was-just-the-beginning-on-the-streets-of-lisbon-the-energized-city-becomes-the-canvas/. [ Links ]

Dickens, L. (2009) The geographies of post-graffiti: Art worlds, cultural economy and the city. Unpublished PhD thesis, Department of Geography, University of London, London. [ Links ]

Gablik, S. (1984) Has Modernity Failed, pp. 103-113. [ Links ]

Ganz N. (2004) Graffiti World: Street Art from Five Continents, London: Thames and Hudson. [ Links ]

Haden-Guest A. (2007), 'BIG ART Inc.' in New York Calling: from Blackout to Bloomberg Berman M and Berger B , London: Reaktion, pp.308-318. [ Links ]

Hoban, P. (2016) Basquiat: A quick killing in art, Open Road Media. [ Links ]

Iveson, K. (2002) The call to the streets II: London, pp. 112-147. [ Links ]

Kimvall, J. (2014) “Mapping an Institutional Story of Graffiti and Street Art”, Lisbon Street Art & Urban Creativity International Conference, vol. 1, pp. 92-95. [ Links ]

Lachmann, R. (1988) “Graffiti as career and ideology”, American Journal of Sociology, pp. 229-250. [ Links ]

Manco, T. (2004) Street Logos, London: Thames and Hudson. [ Links ]

Mirzoeff, N. (1995) “Bodyscape”, Art, Modernity and the Ideal Figure, Visual Cultures, London, New York, pp.147-149. [ Links ]

Reinecke, J. (2007) Street-Art: Eine Subkultur zwischen Kunst und Kommerz, Frankfurt: Transcript. [ Links ]

Received: 01-12-2016; Accepted: 04-07-2017.