“Linking the physical to the social city is the challenge of our times.” (Michael Batty apud Netto, 2016, p. 2)

1. Introduction

Due to the rapid and uncontrolled growth of global urbanization in the second half of the twentieth century and the consequent degradation of the quality of life, especially in large urban centres, the global community was confronted with broad new challenges, which raised a number of issues, among others housing, infrastructure, basic sanitation, and environment. This fact alerted a group of 30 people (scientists, educators, economists, civil servants) who, representing 10 countries, met at the Accademia dei Lincei in Rome, originating in 1968 in the Club of Rome (Club of Rome, 2015).

The concerns of the Club of Rome, especially by Meadows, Meadows, Randers and Behrens III (1972)1, were then expressed in the United Nations General Conferences and Forums, which confirmed a need to reflect on these changes and new challenges on a global platform, which resulted in a conference exclusively dedicated to human settlements, the Habitat I Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development in Vancouver (1976). Subsequently, a new United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN-Habitat), a specialized United Nations (UN) agency dedicated to promoting more socially and environmentally sustainable cities and elaborate urban agendas, was founded in 1978, so that all its future residents have adequate shelter.

In 1983, the United Nations General Assembly created the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), to examine the global environment and development to the year 2000 and beyond. The commission sought to reassess critical problems, to formulate realistic proposals for solving them, and to raise the level of understanding and commitment to the issues of environment and development. The work peaked into the report Our Common Future2, offering an agenda advocating “the growth of human progress through development without bankrupting the resources of future generations”, based on “policies that do not harm, and can even enhance, the environment” (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987).

The following Habitat II conferences in Istanbul (1996) and Habitat III in Quito (2016), in addition to the World Urban Forums (WUF), which were set up in 2001 by the UN and have been held every two years, focused on the sustainable development, rapid urbanization and its impact in communities, cities, economies, climate change and politics (UN-Habitat, 2014). The former Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon emphasized in 2012 the importance of a structured urbanization process and highlighted that “the battle for sustainable development will be won or lost in cities” (United Nations, 2017, p. 10).

Recently, the actual implementation of urban agendas gained attention. As a preparation for the Habitat III conference, the member countries, including Brazil (National Council of Cities, 2015), elaborated national and regional reports to provide evidence-based knowledge on the implementation of the current global state of urbanization and the Habitat Agenda. These reports comprised good practices and tools, both at the policy and intervention levels. Besides, 22 issue papers were elaborated through a collaborative exercise of over 100 urban experts, coordinated by the Habitat III Secretariat, to addressed research areas and highlighted general findings (UN-Habitat, 2016b). The issue papers covered six thematic areas: 1. Social Cohesion and Equity - Liveable Cities; 2. Urban Framework; 3. Spatial Development; 4. Urban Economy; 5. Urban Ecology and Environment; and 6. Urban Housing and Basic Services. All papers were finally compiled into a summary report, to provide background and knowledge, highlighting key challenges, and recommendations on the most significant urban topics taken into consideration within the Habitat III preparatory process. The report served as a background paper for the discussions of the conference and was a departing point for the work of the Habitat III Policy Units to elaborate a “New Urban Agenda”.

According to Clos, the Secretary-General of the Habitat III Conference, the symposium was “a unique opportunity for rethinking the Urban Agenda in which governments can respond by promoting a new model of urban development able to integrate all facets of sustainable development to promote equity, welfare, and shared prosperity” (UN-Habitat, 2016a). The first objective and result of the conference in Quito were that all UN members agreed on the recently elaborated New Urban Agenda (NUA), which should serve as a standard to urbanization in the subsequent years 2017-2036, a guideline for spatial and social organization. It was adopted on 20 October 2016 during the conference and endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly at its sixty-eighth plenary meeting of the seventy-first session on 23 December 2016. According to the committee, the NUA represents a shared vision for a better and more sustainable future. “If well-planned and well-managed, urbanization can be a powerful tool for sustainable development for both developing and developed countries” (UN-Habitat, 2017, p. iv).

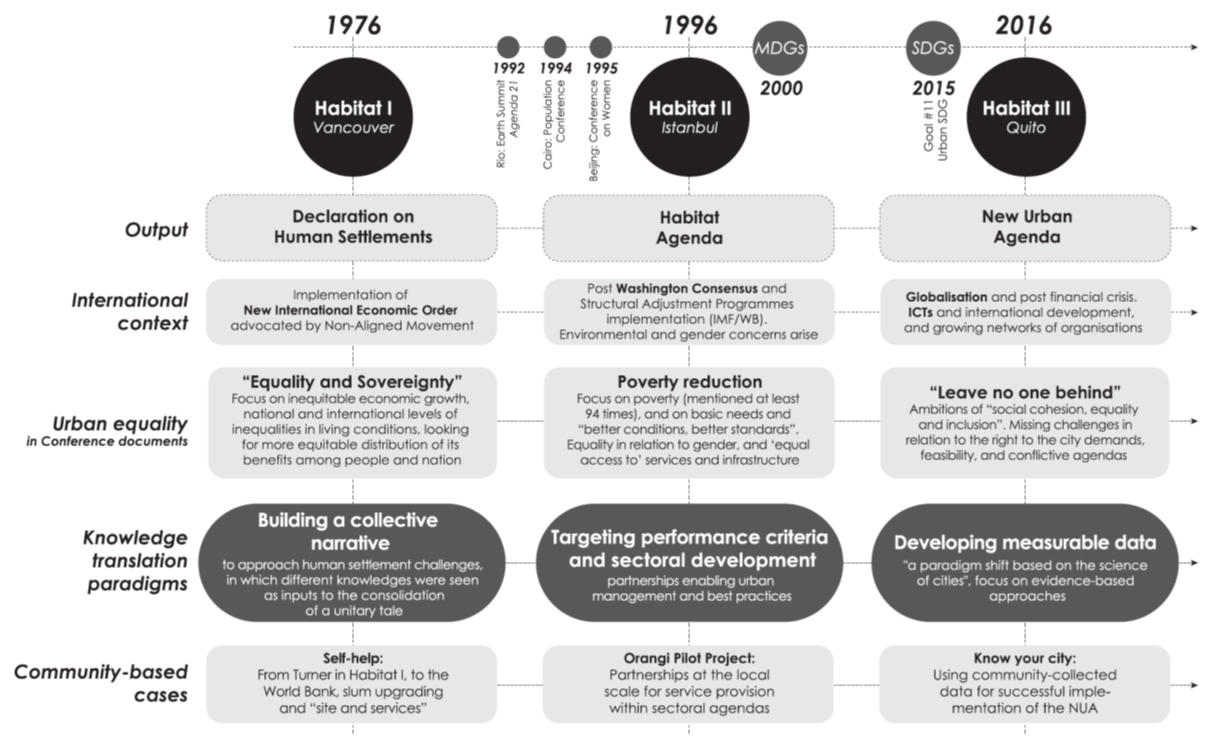

The agenda has several references and milestones related to UN agreements, such as the Rio Summit Declaration on Environment and Development (1992); the Millennium Development Goals Adaption (2000), which were updated in the Sustainable Development Objectives (2015) with Agenda 2030; the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015); the COP 21 Paris Agreement on Climate Change (2015); and others (Figure 1).

Cociña et al. (2019, p. 133).

Source: Figure 1: Knowledge translation and urban equality in Habitat I, II, and III

The 9th edition of the WUF in Kuala Lumpur (2018), which had the theme: 'Cities 2030, Cities for All: Implementing the New Urban Agenda', highlighted the NUA as a crucial instrument for sustainable urban development. Strategies for the implementation of the NUA at the global, regional, national, and local levels were discussed during the meeting.

However, global institutions, like the World Economic Forum, urban experts, and researchers around the globe revealed already gaps in successful implementation and notable differences between countries and regions. Galal (2018) highlights several opportunities for improvement and challenges, such as lack of measurable indicators, need for capacity building, request for strengthened institutional frameworks, enhancement of local ownership, and improvement of still limited private sector engagement. Another summary of challenges for the urban agenda comes from the Davos Forum directly:

The World Economic Forum pointed out the main challenges facing the new sustainable town planning roadmap:

• The New Urban Agenda lacks predefined indicators to measure its progress and leaves the choice and monitoring of results to local governments.

• It takes time, training, specialisation and concerted effort to monitor and correctly evaluate the progress attributable to the agenda.

• Favourable institutional frameworks are needed with adequate regulation, coordination mechanisms at all levels and a clear, accountable government structure.

• Greater participation by local governments is appropriate, assuming more weight, control and power when making decisions.”

• The transformation of cities requires greater cooperation and dialogue between public authorities and the private sector, educational bodies and civil society. (World Economic Forum, 2018 apudIberdrola, 2020)

Alongside the implementation gap, comes the gap in regards to the state of knowledge. As Dahiya and Das (2020, p. 308) outline, this knowledge gap is becoming “increasingly relevant in the global development community”, especially in developing countries, as they “urbanize at a significant pace”. According to Caprotti et al. (2017, p. 375), there is an imminent “need to critically engage with the role of experts, data, measurement and their implications for the production, performance and promotion of specific visions of what could be described as the ‘new urban citizen’”, to wider the debate and shaping of urban agendas like the NUA and the SDG11, especially in regards, how they are “operationalized in urban practice as well as theory”. To narrow the knowledge gap and endorse the dialogue between institutions, the study wants to provide current data, reflect on international urban agendas, and highlight pathways for successful implementation.

2. How do urban agendas approach urban challenges

The theoretical background about urbanization, its implication as well as a common definition about sustainable urban agendas is immanent to understand the conception and intentions, which go alongside with the desired successful implementation. To illustrate current approaches, the scrutinized and deconstructed NUA can serve as a useful example, and on its basis, exemplified the link between urban agendas, the respective implementation, and common urban challenges.

2.1. Definition of sustainable urban agendas

In recent years, the term “sustainable” got quite inflationary and distinguished use in politics, science, economics, literature, and the news all over the world. Especially international agendas, like the SDGs and the NUA3, make extensive use of it. The definition seems to be key for the successful implementation of international guidelines at the national and regional levels. However, to better understand the term sustainability and sustainable development, it requires, first of all, a common definition. In the New Encyclopaedia Britannica, Meadowcroft (2007) states in the article about sustainability:

Sustainability, the long-term viability of a community, set of social institutions, or societal practice. In general, sustainability is understood as a form of intergenerational ethics in which the environmental and economic actions taken by present persons do not diminish the opportunities of future persons to enjoy similar levels of wealth, utility, or welfare. The idea of sustainability rose to prominence with the modern environmental movement, which rebuked the unsustainable character of contemporary societies where patterns of resource use, growth, and consumption threatened the integrity of ecosystems and the well-being of future generations. Sustainability is presented as an alternative to short-term, myopic, and wasteful behaviours. It can serve as a standard against which existing institutions are to be judged and as an objective toward which society should move. Sustainability also implies an interrogation of existing modes of social organization to determine the extent to which they encourage destructive practices as well as a conscious effort to transform the status quo so as to promote the development of more-sustainable activities.

According to Meadowcoft, in the contemporary debate about the term, “sustainability often serves as a synonym for sustainable development”; on further occasions, the definition is associated more exclusively with “environmental constraints or environmental performance”.

Sachs (1974, p. 828), as one of the first eco-socioeconomics, observes that “environment is a dimension of development, and must therefore be internalised at every decision-making level”. His attempt to consolidate a new theory about the possibility of a different development has led to the idea of sustainable development. The most famous cornerstone in regards to sustainable development was however laid in 1987 with the Brundtland Report, introducing environmental concerns to the formal political development sphere and discussing environment and development as one single issue (World Commission on Environment and Development,1987). Nonetheless, some authors identified as well contradictions in the sustainable development thesis of the Brundtland Report (Haavelmo and Hansen, 1991; Goodland, 1991).

Sachs (1993) further fan out the term of sustainable development into five sustainability dimensions and their respective main components and objectives (Table 1).

Table 1: Components and Objectives of Each of the Five Pillars of Eco-development

| DIMENSION | MAIN COMPONENTS | OBJECTIVE |

|---|---|---|

| SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY | - Creation of jobs that allow for adequate individual income and better living conditions and better professional qualification. - Production of goods directed primarily to basic social needs. | REDUCING SOCIAL DISEQUALITY |

| ECONOMIC SUSTAINABILITY | - Permanent flow of public and private investments (the latter with special emphasis on cooperativism). - Efficient management of resources. - Absorption by the company of environmental costs. - Endogenization: rely on your own strengths. | INCREASED PRODUCTION AND SOCIAL WEALTH, WITHOUT EXTERNAL DEPENDENCE |

| ECOLOGICAL SUSTAINABILITY | - Produce respecting the ecological cycles of ecosystems. - Prudence in the use of non-renewable resources. - Priority to the production of biomass and the industrialization of renewable natural inputs. - Reduction of energy intensity and energy conservation. - Technologies and production processes with a low waste rate. - Environmental care. | QUALITY OF THE ENVIRONMENT AND PRESERVATION OF SOURCES OF ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES FOR NEXT GENERATIONS |

| SPATIAL OR GEOGRAPHIC SUSTAINABILITY | - Spatial decentralization (of activity, population). - Deconcentration - local and regional democratization of power. - Balanced city-country relationship (centripetal benefits). | AVOID EXCESS OF AGGLOMERATIONS |

| CULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY | - Solutions adapted to each ecosystem. - Respect for community cultural formation. | AVOID CULTURAL CONFLICTS WITH POTENTIAL REGRESSIVE |

Source: Sachs (1993) apud Filho (1993, p. 134), own translation.

Several other possible compositions illustrate the dimensions of sustainability, as Laura (2004) compiles (Table 2). However, most sustainable urban agendas, including the Agenda 2030 and the NUA, comprise at least the five dimensions indicated by Sachs (1993), by promoting mutual urban development in the social, economic, cultural, ecological, and spatial fields of intervention. Therefore, this definition will be reflected in further work.

Table 2: Selection of possible sustainability dimensions

| DIMENSIONS OF SUSTAINABILITY | AUTHORS |

|---|---|

| Environmental, social, economic | LT et al. Consortium (1998) apud Dobrovolski (2001) |

| Environmental, social, economic, institutional | IBGE (2000); Sepúlveda (2002) |

| Social, economic, cultural, ecological, spatial | Sachs (1993) |

| Planetary, ecological, environmental, demographic, cultural, social, cultural, political, institutional | Guimarães e Maia (1997) |

| Social, economic, environmental, physical, human, psychological, cultural, political | Ribeiro (1998) |

Source: Laura (2004, p.59), own translation.

Though, latterly it has to be alluded as well, how to collaborate within intergenerational ethics and in the creation of diverse regenerative cultures adapted to the unique biocultural conditions of a place. Wahl (2016) argues that there is even a level beyond sustainability when it comes to the designing of regenerative cultures. He highlights the spectrum of human development in a gradient way, starting with conventional habits by staying within the law, green actions with a little less negative impact on environmental aspects, and sustainable rules of conduct in the centre of the range, by trying to avoid additional harm to the society. On the other side of the spectrum come restorative measures, where “humans doing things to nature” and at the far end the regenerative culture, where “humans doing things as nature” (Figure 2). He questions “how we will have to change individually and collectively to create this future” and proclaims, that “we need a collective narrative about who we are and why we are worth sustaining”.

In summary, the word sustainability underwent a process of development in the last decades. The definition of sustainable urban agendas is not always convergent and depends very much on the context where it is applied. In the light of the research question about the implementation of international guidelines on a local scale, it reflects the intention to outlast short-term intervention and policies, which are often owed by short-sighted political activities, concerned about the next legislative period only. However, sustainable urban agendas rather aim to shape urban development based on long-term considerations and aligned with overarching common social, economic, cultural, ecological, and spatial values.

2.2. The New Urban Agenda

As a recently developed international urban guideline, the NUA exemplifies, how urban agendas are structured and eminently indicates how they might be implemented on regional and national levels. It is important to comprehend the link between global urban challenges and the intentions of international agendas to overcome urban deficiencies and shortcomings through the implementation.

The commitment of the agenda comprises an urban paradigm shift regarding how to plan, finance, develop, govern and manage cities and human settlements, including developing and implementing urban policies, strengthening urban governance, reinvigorating long-term and integrated urban and territorial planning and design, and supporting effective, innovative and sustainable financing frameworks and instruments. The call for action invokes all countries with their national, subnational, and local governments to implement the agenda at the regional and global levels, considering different national realities, capacities and levels of development, and respecting national legislation and practices, as well as policies and priorities (UN-Habitat, 2017).

The NUA tries to internalize the new spirit of regenerative cultures with its holistic approach by the living system design, paying attention to quality & quantity, proposing effectiveness, and implementing its measures in patterns and principles, as indicated before in Figure 2.

The agenda highlights three areas of implementation: (1) Sustainable urban development for social inclusion and ending poverty; (2) Sustainable and inclusive urban prosperity and opportunities for all; and (3) Environmentally sustainable and resilient urban development. The national political stakeholders (like the Ministries of Cities) are requested to coordinate their urban and rural development strategies and programs to apply an integrated approach to sustainable urbanization for the effective implementation of the NUA to establish a supportive framework, anchor the effective implementation in inclusive, implementable and participatory urban policies, foster stronger coordination and cooperation among national, subnational and local governments, and support local governments in determining their own administrative and management structures under the umbrella of “integrated planning” (UN-Habitat 2017, p. 24).

Regarding the follow-up and review of the implementation, the agenda wants to strengthen data and statistical capacities to effectively monitor progress achieved and promote evidence-based governance, using both globally comparable as well as locally generated data. The applied interfaces and actions for implementation are based and focused on the five P’s: people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnerships (SDSN, 2015). In this context, Parnell (2016, p. 532) observed, “while the UN cannot define the parameters of a new global urban agenda alone, no other body is as powerful in setting out the normative base or systems of implementation for urban change”.

3. Implementing urban agendas

The implementation of urban agendas is a worldwide challenge, especially considering the knowledge translation. International agendas have to be adjusted and, in some cases, “topicalized” on a national level, especially in developing countries of the global south. The lack of adequate urban data and the absence of baseline studies are in many cases additional obstacles to the process for successful implementation.

3.1. A shift of driving forces implementing global urban agendas through knowledge translation

According to Cociña et al. (2019), Parnell (2016), and others, the existence of serious “global urban agendas” can be assumed, which get attention and support in all parts of the world. They base their assumption on international guidelines, charters and directives developed since the turn of the century, especially the elaboration of the SDGs and the inclusion of an explicit urban goal (Goal 11), but as well the NUA and other urban agendas. On the other hand, “local and global planning practices are in constant interaction” and “knowledge translation” in global urban agendas play a key factor for success. Cociña et al. (2019, p. 131) furthermore note that community-based actors located on the ‘margins’ of global processes have a central role in this process. They argue that “there is a growing field of inquiry catalysing around the dynamics of ‘global’ urban governance” and “different forms of knowledge circulate and influence each other”. Perception guides experience, which needs to be systematized (Kant apudBorges, Moreira, Martins, 1990). The urban knowledge transfer process started already with the Club of Rome I the 1960s and the formation of the Habitat I Conference in the 1970s, and is still ongoing since then, with a recent peak in the perception and visibility due to the alignment with other sustainability agendas and environmental movements like the climate change mitigation and adaptation programs or global warming awareness-raising campaigns. The mentioned immanent knowledge transfer affects all global citizens on multiple levels and scales and is a nonlinear process. Therefore, knowledge translation should focus on methodologies, which “involve encounters between various forms of planning research and planning practice”. As one example can be named the research-practice dialogues of the Habitat III preparation policy unites and their elaboration of the 22 issue papers, which paved the road for the later on agreed NUA. The agenda itself enhances explicitly the “knowledge-sharing on mutually agreed terms”. To do so, it calls in paragraph 157 for

(…) robust science-policy interfaces in urban and territorial planning and policy formulation and institutionalized mechanisms for sharing and exchanging information, knowledge and expertise, including the collection, analysis, standardization and dissemination of geographically based, community-collected, high-quality, timely and reliable data. (UN-Habitat 2017, p. 39)

However, the classic top-down process is no longer the only and favourable way for knowledge translation. Rodríguez & Sugranyes (2017, p. 165) even accused the NUA of being “wishful thinking based neither on the present nor the past” as almost half of the world population still live in other kinds of human settlements, a challenge which requires a different set of knowledge and tools to those that emerged from the Summit’s spaces of exchange. Harrison (2006, p. 324) observed in this context, that different regions in the south are the locus of differentiated modernity. He mentions “a growing body of work that shows how the recovery and deployment of subalternised knowledge and practices materially impact the local outcome of global forces”. Watson (2012, p. 329) complemented that “planning ideas no longer move only from global north to global south and that there are many cross and counter currents, yet it seems likely that traditional north-south flow is still dominant”. Besides, Parnell (2016, p. 533) states, that “the clarion call of major southern nations led by Brazil and other Latin American nations, who are now much more prominent and powerful within the UN system than in its early years when northern powers dominated”. Bearing this in mind, also community-based actors and grass root level movements have been recognized as cornerstones for successful implementations of international urban agendas. Particularly, southern urban theories have emerged as explicitly relevant to the international discussion and development of new urban concepts (J. D. Robinson and Parnell, 2011). They are nowadays often supported not only by international government institutions like World Bank, Development Aid agencies, or UN-Organizations but also by a wide range of corporate non-governmental, philanthropic organizations, and private actors like the Melinda & Bill Gates Foundation or Habitat for Humanity. Cociña et al. (2019, p. 139) “understand knowledge translation as a space of negotiation and unveils the mechanisms through which these processes can become vehicles for challenging inequalities” and “the growing presence of the urban agenda in multilateral and global forums (…) is particularly challenging as the definitions of ‘who is a planner’ in local contexts becomes less clear”. Therefore, “in the context of growing complexities in the international setting, at the local level the of implementing ‘global’ agendas that pursue social justice needs to recognise the variety of existing knowledges”. In a nutshell, knowledge translation can’t be seen as a mere top-down or north-south process, but rather as knowledge transfer and exchange of good practices, regardless of its origin. Global urban agendas should be shaped accordingly, and internationally agreed indicators, and explicitly including indicators from the global south, can help to benchmark, monitor and follow-up the progress of implementation.

3.2. Research gap of the global south

During the bibliographic review and the search for international examples of urban agenda implementations for this article, surprisingly few sources were identified in the global south, especially narrowing down the search to journals with high impact factors. Several articles have a focus on European cities and their agendas. However, relatively little comparative researches where publicized, that stretches across the global north-south divide and through contexts of poorer cities. Walton (1982: 34) observed in his review of comparative urban research:

In the short space of the last decade urban social science has undergone a revolution. Great strides are now being made in the elaboration of a new paradigm. Most of this work, however, is not really comparative and its geographical focus has been on the advanced countries of Europe and North America.

Robinson (2011, p. 2) identified in her position paper this division phenomenon of research in urban studies and appeals “for an international and post-colonial approach”. According to her, contrary to other fields of studies, urbanist researchers are still reluctant to comparative studies, although there are existing strategies and methodologies for comparing cities. She bases her theory on the privileged sites for the invention in “advanced industrial, wealthier countries” and “movement of developmentalism” withdrew on theories of modernization. It was previously assumed that the experiences of wealthy and poorer cities held little relevance for one another and wealthier cities claimed universal knowledge about all cities. However, several examples prove this assumption wrong. Researches on urban participatory budget planning, which had their origin in the global south, are nowadays worldwide explored, especially in the northern hemisphere (e.g., Carolini, 2017; Crot, 2010; Pimentel Walker, 2016). New urban transportation trends are under investigation, from cable car technologies developed in the alps and now connecting informal settlements in Bolivia and Colombia, till vehicle fleet technology changes like new Chinese e-transport alternatives (scooter, drones, etc..), spread out in cities all over the globe, indifferent of their location and current development status (e.g., Álvarez Rivadulla; Bocarejo, 2014; Namdeo et al., 2019; Wey, Huang, 2018). As globalization progress and cities, new urban sprawls, and emerging megalopolis all over the world get interconnected, the barriers and boundaries between underdeveloped and technologically advanced urban agglomerations vanish. In a conclusion, Robinson (2011, p. 19) prompts for a “revitalized and experimental international comparativism”, to diminish the research gap between the global north and global south, which is also the aim of this study. In this regard, the NUA attempts to promote in paragraph 146 specifically

(…) opportunities for North-South, South-South and triangular regional and international cooperation, as well as subnational, decentralized and city-to-city cooperation, as appropriate, to contribute to sustainable urban development, developing capacities and fostering exchanges of urban solutions and mutual learning at all levels and by all relevant actors. (UN-Habitat 2017, p. 38)

The article claims therefore to contribute and narrow down the research gap of the global south, by exploring the sample situation in Brazil and promoting alternative mechanisms for the implementation of international urban agendas in the global south.

4. The sample situation in Brazil

Exemplarily for other developing countries, the urban evolution, and the situation in Brazil, as well as its planning policies, can be scrutinized, to capture the actual challenges implementing international guidelines like the NUA on the national level. To execute the analysis, a vast theoretical review of published reports and articles was undertaken, complemented by inside knowledge gathered via the day-by-day work of the authors within Brazilian key institutions (Ministry of Cities, Ministry of Environment, and the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE)). Further identified gaps and inconsistencies were then complemented with the information provided by other public servants and policy-makers, mainly from the above-mentioned institutions. In a bigger context, the article also holds stakes and profits from the research of two current Ph.D. theses in Brazil, developed within the Post-Graduation Program of the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism (PPG-FAU), at the University of Brasília.

Since the first Habitat conference in 1976, Brazil took its stakes and participated actively in the discussion and elaboration of recommendations for urban development. Also, in 2016 and the years before, Brazil committed itself to the preparatory process for Habitat III. Nonetheless, the country is struggling, alongside with most other developing countries, to implement the agreed recommendations on a national and local level, due to the lack of indicators and guidance. Brazil is far from overcoming the modern urban challenges mentioned in the NUA, at least on a broader scale.

4.1. The urban evolution and current situation in Brazil

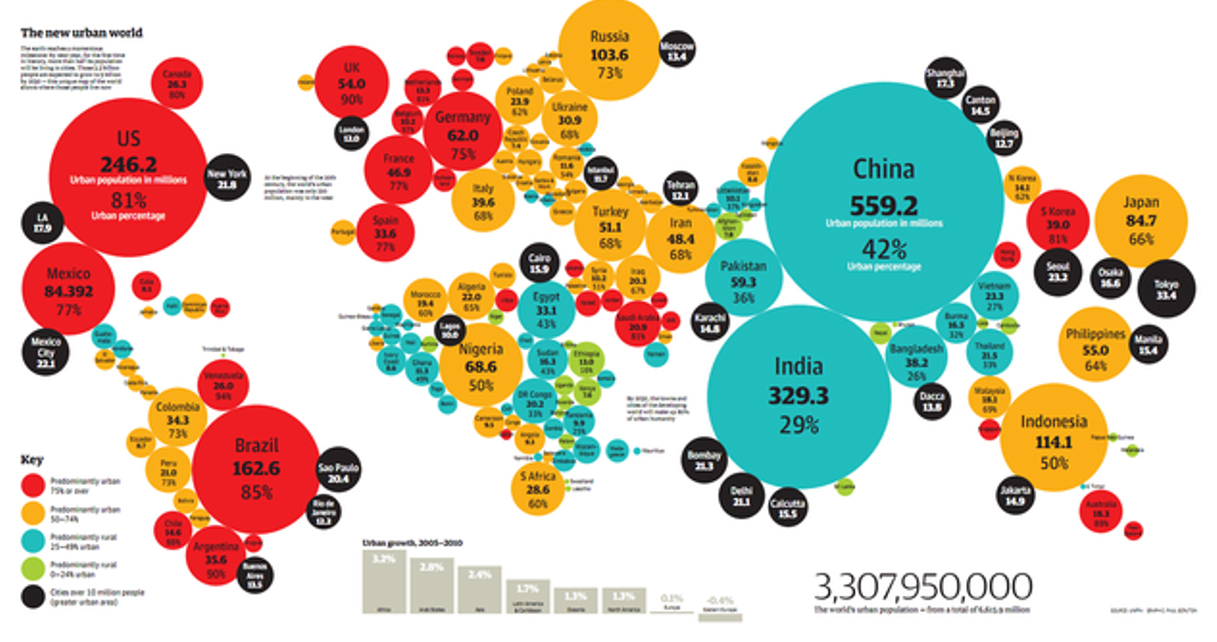

In recent years, the world in general, and Brazil in specific has gone through a rapid process of urbanization (Figure 3) (Gobbi 2016; Vidal and Scruton 2007).

In 2010, when the last official census of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) was undertaken, the degree of urbanization totalled 84.4% (IBGE, 2011b). These figures were consolidated in 2015 by the National Household Sample Survey (PNAD), which estimated the urbanization rate towards 85% (PNAD, 2015). Consequently, most economic production is concentrated in cities. In 2018, the 83 Brazilian metropolitan regions and urban agglomerations are inhabited by more than 50% of the national population. In contrast, about 85% of the 5,570 municipalities have less than 100,000 inhabitants (IBGE, 2018). Currently, the highest rates of urban growth are concentrated in medium and small cities.

The growth of cities, in number and surface, challenges the structures of administration and planning of municipalities and metropolitan areas. As a result, poor and poorly distributed technical infrastructure (energy supply, transportation, sanitation, including solid waste, communication), and insufficient public and community facilities appears, which contributes to social disparity and environmental problems. Informal settlements (slums) are often located in risk areas such as flooding banks and slopes. The 2010 IBGE census accounted for more than 11.4 million people (equiv. 6.0 % of the total population) living in subnormal agglomerations (IBGE, 2011a). Though, other more recent estimates indicate that there are already about 45 million inhabitants living in precarious urban areas (e.g. GIZ, 2018).

4.2. Urban and metropolitan planning policies in Brazil

Urban planning and development are, in principle, municipal responsibilities. However, with few exceptions, these entities have insufficient resources for management and scarce capacity for planning and implementing actions. Costa, Matteo & Balbim (2010) point out that the rapidity and complex form of the transformations that occurred in Brazilian cities in recent years turn any planning and territorial management initiatives into a major challenge.

In 2003, the law to create the ‘Ministry of Cities’ was enacted, which was responsible for drafting and coordinating urban development policy and sectoral housing, environmental sanitation, and urban mobility policies. Additionally, it defines the allocation of federative resources for these sectors. The Secretariat for Regional and Urban Development (SNDU) within the ministry is responsible for supporting municipalities in territorial development processes, in the elaboration of urban development plans, property rights issues and the management of settlements in risk areas.

In 2001, the City Statute (Law 10.257/2001) was promulgated, which sets forth general guidelines and norms for urban development, focusing on sustainable and democratic development that help guarantee the right to the city (Planalto, 2001). The act was internationally recognized as a model of urban policy to follow, a fact that led Brazil to be included in the UN-Habitat honour roll in 2006 (Fernandes, 2013). The current Brazilian urban policy is the result of intense debate of several sectors of society for the implementation of urban planning policies appropriate to the problems of cities in the country. Such discussions have been held since the first Habitat Conference held in 1976 in Canada. Regarding effects, previous Habitat conferences were of fundamental importance in shifting the global approach to urban issues. The global agendas emerging from the conferences influenced the affirmation of rights and the implementation of public policies for the construction of fairer cities. Galindo & Monteiro (2016, p. 26) state that:

In Brazil, the effects of Habitat II can be perceived in the perspective of urban perspectives. A significant example was the adoption of Constitutional Amendment (EC) No. 26 of 20004, approximately four years after the conference, which included the right to housing among the rights expressed in the Federal Constitution of 1988 (Article 6)5. This legislative change, two effects stand out: the right to housing becomes a fundamental right, and therefore has to be effective for all, and starts to form the role of the guiding rights of all Brazilian state legislations and policies.

They confirm that another formalized national legal framework post-Habitat II was the City Statute, which brings in its core a series of advances, obligations to public managers, and explicitly the right to a sustainable city, although with a limited restriction on access to basic services. One of the most important guidelines established by the City Statue was the obligation to prepare the Plano Diretor (Master Plan) in all municipalities with more than 20,000 inhabitants. About 90% of the municipalities prepared the plans. However, there is a need for improvement of their effective implementation, as regulations often overload the capacity of municipalities. They must be realistically adapted to the diverse capacities of small and large municipalities. Recently, the Metropolis Statute (Law 13.089/2015) established that the municipalities of metropolitan regions and urban agglomerations should prepare master plans compatible with the Plano de Desenvolvimento Urbano Integrado (Integrated Urban Development Plan) (Planalto, 2015). All of these Brazilian laws and statutes should foster the implementation of the 2030 Agenda and strengthen sustainable urban development at the local level, as envisaged by the NUA. Yet, instruments for urban development must be in tune with environmental and territorial planning devices, as well as civil prevention and protection. Especially in the National Adaptation Plan (PNA), cities play a leading role in climate change processes and are being addressed in their chapter (MMA, 2016). Nevertheless, the role of cities as a key player in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and the impacts of climate change is not systematically considered in the PNA. There is a lack of practical experiences that could be implemented in urban planning and development.

4.3. The urban planning policies in Brazil and the adaption to the New Urban Agenda

In 1996, at Habitat II in Istanbul, urbanization was identified as an opportunity and cities as vectors of development. The Istanbul Conference was fundamental for the international recognition of the right to housing and influenced important milestones in Brazil, such as the approval of the previously stated City Statute (2001), the creation of the Ministry of Cities (2003), and then the Council of Cities (2004). According to the National Report (National Council of Cities, 2015), from then on, the Brazilian government developed policies to meet the challenges of the cities, by setting public targets and massive investments in basic sanitation and urban mobility, and the expansion of housing policies led by the Minha Casa, Minha Vida (My House My Life - MCMV) Program since 2009.

According to Marguti et al (2018), important normative references were approved within the framework of the extinct Council of Cities and the cycle of national conferences, such as the National Policy of Urban Development; the construction of the National System of Urban Development; the creation of the Policy for the Prevention and Mediation of Urban Land Conflicts; as well as the attempt to integrate urban development policies into the MCMV program.

Despite the normative advances, it must be noted, however, that these references still need to be made effective. With the establishment of the City Statute, the Master Plan gained greater centrality and became the main instrument for city planning. Contrary to the technocratic and centralizing aspect that historically marked the drawing up of executive plans, after the City Statute, the Master Plan began to contemplate, in its construction, the democratic participation.

Among the issues addressed in the National Report, suggested by the issue papers or summarized in the ten policy papers, one can say that the greatest advance that Brazil has had in the last twenty years in urban development was the legal frameworks and institutions created. Galindo & Monteiro (2016, p. 29) point out that:

Although not guaranteeing the effectiveness of policies, the norms established in the period allowed the creation of a series of institutions and legal institutes, reinforcing the issue in the governmental scope and establishing participatory and democratic guidelines.

Although there is still much to be done, the institutional environment provided the empowerment of the population, culminating in conditions for greater participation in consultative and decision-making processes. Urban councils of diverse themes were created, the process of direct democratic elaboration or representative of master plans, and, in some cases, until the establishment of participatory budgets. Public hearings, oversight by external control bodies, prosecution charges, and popular pressures spread throughout the country. Through the examples cited above, it can be seen that the Brazilian urban development agenda established during the decades following Habitat II was committed to initiatives that promoted the follow-up of what was established at the Istanbul conference. It is from this point of view, that Brazil needs to lay the focus towards the coming years and establish goals that seek the structuring of policies in accordance with strategies aimed at sustainable urban development, to fully adopt the NUA and its intended recommendations for implementation.

4.4. Local challenges in Brazil in regards to international guidelines

During conversations with Rafael Greca, mayor of Curitiba, and his civil servants of the city administration in 2018/19, a lot of interest, but limited knowledge about international guidelines, like the NUA, was encountered at the local level. The same observation was confirmed during site visits of the SNDU staff within the framework of the German cooperation project ‘Supporting the National Agenda for Sustainable Urban Development in Brazil’ (ANDUS) in five pilot cities and one metropolitan region, dispersed in several regions in Brazil, in the same time interval.

Despite the advances presented by the Brazilian post City Statue guidelines, one of the central problems for urban planning is the composition of a sectoral policy model detached from the territorial pattern that characterizes the Brazilian urban model (Algebaile, 2008). There is, for example, a structural misalignment regarding land use in Brazilian cities and the application of the directives proposed in the municipal Master Plans, as well as experiences of a social sectorial policy that predominates over the national territory management, materializing in 60% of the Master Plans, but they are not linked to land policies capable of granting access to land and housing policy with good urban insertion. This logic is replicated, for example, in the experiences of private and public enterprises such as the urban infrastructure investments of the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) and the MCMV Program.

Despite that, Brazil also has very significant challenges regarding urban territorial planning. To better understand the link between, it is necessary to remember the different legal processes that cover the institutional urbanization that occurred in the last thirty years after the promulgation of the Federal Constitution of 1988 (CF/1988) and culminating in the proliferation of urban regions throughout the national territory (Costa, Matteo, and Balbim, 2010). It is important to point out that the phenomenon of institutional urbanization is not accompanied by the historical process that expresses "the structure, the form and the socio-spatial dynamics, and assumes some particular features in capitalism". Thus, it can be seen that this process of recent urbanization in Brazil cannot be understood by the strict sense of the manifestation of the classical urbanization process, constituted and characterized by integration with the core city, configuring an expanded territory that shares functions of common interest. Faced with this, Costa, Matteo & Balbim (2010, p. 4) add that:

(…) in Brazil, this discrepancy between the recognition of a metropolis - that is, the identification and characterization of the process of metropolization - and the institution of an RM6 has been deepened, since the changes brought by CF 7/ 1988. The Brazilian metropolises, especially those defined as such in the 1970s, have their RM status coupled with the historical process that led to the production of the metropolitan space.

Given the particularity of the Brazilian metropolitan process of thinking about the construction of a federal metropolitan policy that goes beyond the simple combination of municipal urban policies, it is necessary to work on the articulation of plans, policies, and systems. One cannot detach itself from the regional policy, nor the policy of territorial planning for the construction of stable metropolitan arrangements. It is also necessary to overcome the practice of the "transfer desk" of the federal government for sectoral programs.

The Federal Constitution of 1988 elevated the municipalities to the condition of federated entities, with the autonomy to organize and manage a series of public services that passed their competence, transforming the responsibilities agenda of the municipalities. Currently, the political-administrative organization of the Federative Republic of Brazil comprises the Union, the 26 states, the Federal District, and the 5,570 municipalities, all of which are autonomous.

The challenges to urban spatial planning in Brazil, as stated before, gain a metropolitan dimension with the Federal Law 13.089/2015. The Metropolis Statute arises to direct the common planning of Metropolitan Regions and urban agglomerations instituted by the States, establish guidelines for the integration of actions among the municipalities that compose a Metropolitan Region. According to the Statute, the Metropolitan Regions should elaborate the Integrated Urban Development Plan as a tool for metropolitan policy and "(…) should consider all the municipalities that make up the urban territorial unit and cover urban and rural areas" (Planalto, 2015).

Given this, it is understood that the development of countries is directly related to the role that their cities and metropolises play in the network of cities in the era of globalization. In the cities and metropolises, the greatest inequalities and opportunities for employment, income, and production are concentrated. In Brazil, sustainable development requires, necessarily, the equation of urban problems. In spite of the economic and social advances of the 2000s, the urban infrastructure has not presented equivalent advances, especially in the main cities of the country, since the deficit of this item remains high and requires financing and management solutions for the metropolitan regions.

The big question about urban and metropolitan planning in the country is related to the lack of organizational structures of the Brazilian municipalities and the struggle for an embracing agrarian reform in Brazil, which the Land Statute (Law 4.504/1964) could not solve. Since the 1970s, the interaction between peasant movements, the progressive church, and the transnational network of human rights has converged into the idea that land ownership is a human right, which not only has marked the character of the struggle for land in Brazil but has also influenced how the human rights movement has been constructed in the country and how it has taken its place within the transnational network of human rights activism.

The Federal Constitution of 1988 passed the task on t1o the states, to institute and manage the urban and metropolitan regions. However, although the City and Metropolis Statute are important instruments for directing urban policies in urban areas in Brazil, it is the states’ responsibility to establish the management bodies of the regions. They are, therefore, not territorial units of the Brazilian State such as the municipalities and the Units of the Federation. Although there is, in theory, a centralization of the management of these areas by the states, there is no common organization model that allows the characterization of urban policies in Brazil. This configuration makes it difficult to manage and implement development plans and projects common to the municipalities that are part of the institutionalized urban territory.

Therefore, even with concepts, laws, planning, and management tools that are well advanced in international comparison (e.g. in regards to participatory budgeting), they do not live up to the sustainability requirements of urban planning and development in Brazil, considered by the NUA. Reasons for this are, among others, are the low capacity of planning and implementation of the instruments by the municipalities and the lack of coordination mechanisms between sectors and between administrative levels.

The central challenge at the national level is, in particular, the improvement of urban planning and management tools, including urban regulation and urban interest regulation. Such a challenge should address the sustainable use of natural resources and spaces available and adapted to climate change processes, as existing regulations are incomplete, partially incoherent, and poorly operational. Mechanisms for intra and inter-institutional cooperation and within the three spheres of government need to be improved.

4.5. Recent political developments in Brazil

Unfortunately, the economic crisis that has hit Brazil since 2014 had impacted the Federal government's budget and consequently several areas of strategic planning for the country's development. The economic crisis was also accompanied by a deep political crisis that culminated in a process of presidential impeachment of Dilma Rousseff in 2016 and the alteration of the Brazilian governmental structure. The advances in public policies in several areas of strategic planning, that occurred in the previous decades, have recently undergone significant changes in their structures, but still without major relevant impacts about the resumption of economic growth and urban development in Brazil. In 2019, due to the political change and election of liberal, right-wing, Jair Messias Bolsonaro in late 2018, several ministries underwent a drastic reorganization. Some ministries received a revaluation, like the Ministry of Economy, which gained the force of a “super”-ministry, absorbing the former Ministry of the Economy, Ministry of Planning, Budget and Management, Ministry of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade, and Ministry of Labour and Employment. Regrettably, also the Ministry of Cities lost its unique feature and merged, together with the Ministry of National Integration to the new Ministry of Regional Development (MDR)8. In 2020, the housing programs MCMV was replaced by the Casa Verde e Amarela program. The alteration of the program, as well as the extinction of the Ministry of Cities in 2019, demonstrates the urgency of the current government to break with the main projects prepared by the previous government. This restructuring and shifting of political priorities might jeopardize current urban strategies, especially all urban planning initiatives initiated under the previous centre-left wing governments since the creation of the Ministry of Cities in 2003, including the jolt implementation process of the NUA in Brazil.

5. Conclusion

Since 1976, the year of Habitat I, local administrations and non-governmental organizations have gained importance in the management of cities and promoted an advance in political awareness about “urbanization of poverty” and environmental unsustainability in the growth of cities, especially in developed countries. International non-binding doctrinaire urban agendas like the NUA try to encourage mainly public stakeholders and decision-makers to raise consciousness about the challenges of the new urban era and point possible pathways to overcome the same by implementing the agenda through supportive political framework activities and traditional hard policy mechanisms.

As highlighted previously, all kinds of cities and settlements, especially in developing countries like Brazil, but also in already developed countries, are confronted with urban challenges on multiple levels. The unstructured growth and concomitant urban sprawl are not only since the last century one of the main tasks of human mankind. Reasons are multiple, as pinpointed in the previous chapters. New regulations often overload the capacity of city administrations and must be realistically adapted to the diverse capacities of small and large municipalities. Organizational structures, planning instruments, and coordination mechanisms have to be strengthened in a broader sense.

International guidelines like the NUA try to mitigate these challenges, structure the irreversible process, and identify steps and procedures towards a more sustainable urban development. These agendas can’t be seen as standalone directives to be implemented on a political level. To preserve and enhance the urban values, the challenges have to be tackled on different levels and scales, simultaneously through scientific and ethical dimensions. Urban agendas should therefore be located in the context of other international guidelines. To successfully overcome the urban challenges, the joint forces of other development driving forces are required. As examples, one can name the SDG target 17 “Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development”, through the use of technology, capacity-building, policy and institutional coherence, multi-stakeholder partnerships, monitoring, and mutual accountability. Just with a holistic and mutual approach, the current uncontrolled growth of global urbanization can be transformed into prosperous cohabitation for future generations and set the global vision of sustainable urbanization for the next decades.

Besides, alternative mechanisms like knowledge transfer and exchange of good practices are necessary for effective implementation. In this regard, the potential of south-south and south-north exchange is still very much under-exploited! Furthermore, the introduction, monitoring, and follow-up of national and regional indicators are required, to benchmark and measure urban development on a local scale. Apart from the political commitment of the public sector, the private sector, the academic sector, and civil society must be involved in a successful integrates implementation. Though to increase the participation of these sectors, broad dissemination of urban guidelines, extensive education, and training are required.

In Brazil, urban development and sustainability are issues recently reviewed jointly. However, the management of the environmental issue is a serious ongoing challenge in the current Brazilian government. At present, a sustainable development agenda is discussed through the National Urban Development Policy (PNDU) with the elaboration of Sustainable Urban Development Goals (ODUS)9. The formulation of the ODUS provides for a national participatory process that results in the involvement of representatives of municipalities and states, government agencies, spheres of government, academia, organized civil society, and strategic actors, creating an environment of co-creation compatible with the objectives of a policy that is capable of meeting the diversity of Brazilian municipalities, with direct impact on the territory. If carried out, this will be an important action for the creation and strengthening of public policies, which aim towards sustainable urban development in Brazil. However, it can be concluded that the major challenges Brazil faces are related to the intense instability of the current political and economic conditions which the country faces since 2014 but deteriorated through Covid-19 and political unrest in 2020. As a result, interruptions of projects for the implementation of policies and agendas in the country can be expected at all times. Based on the case of Brazil, with all the advancements and setbacks in Brazilian urban policies, it can be concluded, that the impact of international urban agendas at a national and regional is still very limited and the high expectations in most developing countries underachieved.

Hence, as mentioned before, special attention must be paid by the national governments and local bodies to the intrinsic value of sustainability and the persistence of the long-term transformational change intended to be triggered by national and international urban agendas and guidelines. Only if they fully commit to the cause and streamline agendas alike crosscutting issues through all governmental entities, national ministries, regional administrations and local bodies, a changing of the course of sustainable urban development policies is possible, and the desired impact feasible.