“Participation is still to be invented by trial and error. No method exists, no rationality: the unconscious, the naïve, the atavist, the dreamer, the exogen, the ecologic (all universal qualities) may help to construct a practice. It will be analyzed later.” Lucien Kroll

1. Introduction

In the South American context, Asuncion is a city like many others. Its residents coexist with floods, traffic jams, epidemics, violence, and social inequality. Asuncion is the capital of Paraguay, a country historically ruled by representatives of the society’s wealthiest strata, often most concerned with meeting the demands of the groups that financed their election campaigns rather than the public interest. The very notion of what is public and what is common seems understandably vague and fragile for a population whose socio-economic indicators suggest deep gaps: for example, the average number of years of schooling - 8.4 (UNDP, 2013) - ranges below the continent’s average, and GDP and Per Capita Income are among the lowest in the region , as almost a third of the country’s citizens live below the poverty line. The energy sector, led by the Itaipu Binational Hydroelectric Power Plant in consortium with Brazil, is a crucial contribution to GDP, making Paraguay, on the other hand, the world’s fifth-largest exporter of electricity. The public company Itaipu Binacional funds numerous social and cultural projects in Paraguay, including the PlanCHA, the Master Plan of the Asuncion Historic Centre, examined in this article.

The country has 6,461,041 inhabitants (DGEEC, 2012), a significant portion of which being concentrated in the capital urban area. Indeed, with almost 2.6 million residents living in 28 municipalities, the Asuncion Metropolitan Area’s population multiplied by five in the last forty years, gathering 38% of the total country’s population and 65% of its urban population. In the same period, the population of the city of Asuncion lasted practically unchanged, counting 529,433 people, in 2012 (ICE, 2014). If the number of city dwellers remained roughly constant, the central area figures have not ceased to decrease, reducing from 11,054 residents in 2002 to 6,928 people in 2012 . To this latter number, however, we must add the estimated 10,761 residents of the Chacarita neighbourhood (DGEEC, 2014), an extensive shantytown area that, unlike some Paraguayan urbanists, we consider to be a part of the Historic Centre.

From a historical and cultural point of view, Paraguay is nevertheless an unparalleled country on the continent. The Guarani indigenous culture, language, customs, and cuisine are part of the entire population’s daily life. About 90% of Paraguayans, even non-indigenous ones, are fluent in both official languages: Spanish, inherited from European settlers, and Guarani, spoken in the region since pre-colonial times (Fernández, 2015). This mixture owes much to the Jesuit Guarani missions, which, from 1609 onwards, helped to bring local peoples and foreign colonizers closer, teaching crafts to the first, learning and systematizing their vernacular practices. Above all, the Jesuit priests produced the writing of the Guarani language to preserve it. The ruins of their missions range today among the most prominent historical monuments of the country. Besides, during the nearly six decades Paraguay remained closed to outside countries - from its independence from Spain in 1811 until the end of the Triple Alliance War in 1870 -, a local state-owned proto-industry was developed, especially in the iron and steel, naval, railway, and textile domains. A public education system had been implemented throughout the country, including rural areas, as part of numberless initiatives that differed from neighboring countries, which were indebted and submissive to the major economic-military powers of the time (Galeano, 1971).

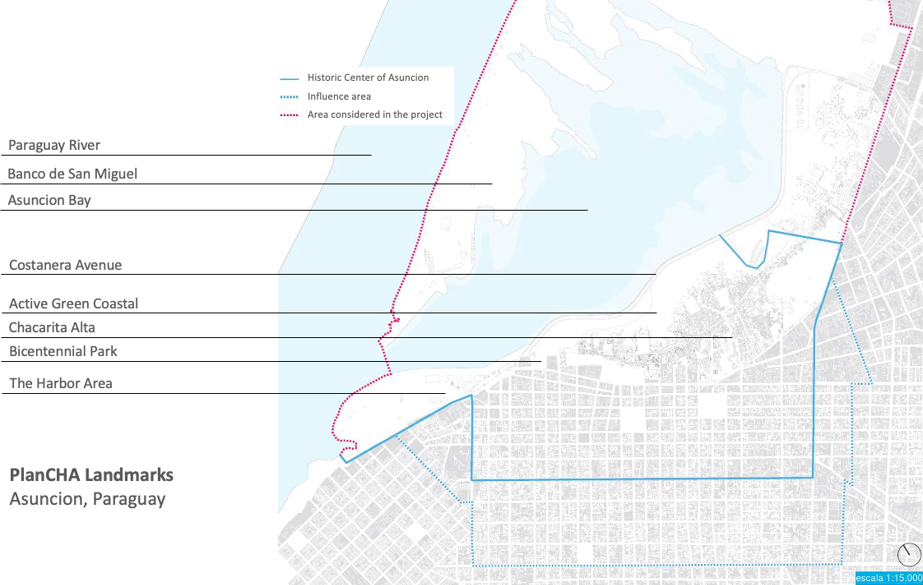

The Historic Centre of Asuncion - CHA in the Spanish acronym - keeps countless physical witnesses of this history. It houses, for instance, the first railway station in South America, which was inaugurated in 1854 to connect the harbor to productive areas across the country. The streets’ layout, the blocks’ parcelling, and geographical location is a physical and silent report on grand decisions of the past that still influences the city’s present. The post-war reconstruction produced a large number of architectural examples, remarkably well preserved to this day. And despite its emptying to the benefit of new urban areas, the centre of Asuncion still plays a high symbolic role for the whole Paraguayan society, as it shelters the headquarters of almost every public and governmental institution of the city and the country, and appears as the favorite stage of all major civic, political, and cultural spontaneous manifestations. Such a condition generates an impressive urban dynamic in its narrow streets. Although there are no reliable statistical records, the figure of one and a half million people entering and leaving the region daily, most of them in individual vehicles, seems well accepted . Called locally Casco Histórico (Historic Shell), this area of 180 hectares, its memory, present, and future are the PlanCHA’s prime object of study and intervention.

This article seeks to examine the formulation, implementation, and reasons for suspending the Master Plan of the Historic Centre of Asuncion (PlanCHA). Instead of a traditional master plan, the winner proposal of the international competition organized by the country’s National Government in 2014 is a master process composed of dozens of top-down and bottom-up participatory actions, articulated by ten initial strategies. Our research on PlanCHA is part of a series of investigations ongoing at Nomads.usp, the Center for Interactive Living Studies of the Institute of Architecture and Urbanism, University of Sao Paulo, Brazil, on participatory decision-making processes concerning urban interventions in several cities across the world. As in the case of Asuncion, Nomads.usp research prioritizes urban intervention plans that, in addition to face-to-face actions, include digital participatory platforms. Our research on PlanCHA aimed to understand the issues involved in the implementation of an action plan that included and depended totally on the participation of public managers, politicians, non-governmental organizations, universities, real estate agents, and traders for its success, in a capital city whose population has virtually no experience of participation in public decision-making processes. We were also interested in verifying whether the online digital platform made the communication between the various actors easier, as expected by the Plan’s organizers. Finally, the article lists some hypotheses for the Plan’s interruption, categorized for administrative, political, and socio-economic reasons.

The text presents and discusses both the proposal itself and its implementation process during the following three years: the historical, socio-political context, the strategies, the steps implemented, and the main reasons leading to its interruption in 2017. In that year, researchers from our Centre interviewed the Ecosistema Urbano team in Madrid. In Asuncion, we met their Paraguayan partners - the team of architects who implemented the project locally -, as well as historians, members and former members of national and local governments, real estate agents, community representatives, cultural producers, residents, and academic researchers. Furthermore, we made several technical visits to the Asuncion Historic Centre recorded in audio and video and studied historical, urban, demographic, academic, and journalistic documents. Technical visits helped us immensely to understand many local urban issues and have enabled interviews with local experts and informal conversations with residents. However, bibliographic research was crucial to clarify and deepen aspects mentioned in the interviews or perceived in technical visits. It also provided a historical background that helps to explain the Historic Centre’s current conditions. On the one hand, the research’s theoretical framework draws from a systemic understanding of the city (Morin, 2005) and collaborative processes of urban design, and, on the other hand, from the theoretical-practical framework of the so-called Temporary Urbanism (Diguet, 2018) and its bottom-up dynamics.

2. CHA, or the Historic Centre of Asuncion: a brief timeline

Founded in 1537, Asuncion is one of the oldest cities on the entire American continent. It had great importance among the overseas colonies of the Spanish Crown in its first ten years of existence as a supplying port for the expeditions that sailed up the River Plate to Peru, in search of already known large silver deposits. From 1547, however, the discovery of easier access to such deposits from the Pacific Ocean coast relegated the town to oblivion until the Spanish province of Guaira was created in 1617, and Asuncion was appointed as its capital. As the only colonial capital distant from the ocean, Asuncion’s relevance depended on its harbor, where commercial exchanges with Buenos Aires, Montevideo, and Spain took place.

The region of today’s Historic Centre corresponds roughly to the settlement area consolidated in 1541 by the Spanish conqueror Martínez de Irala on the banks of the Paraguay River. On the path of the winding, dusty streets of the original settlement, Rodríguez de Francia, the first republican ruler after independence, overlapped in 1811 a rational and straight grid that remains to this day (Rubiani and Tramontano, 2018). During the thirty years the self-appointed Dictator Francia ruled Paraguay, he extinguished Parliament and banned political parties, closed the country’s borders to make it less dependent on external influences, limited powers of the wealthy class, and declared public all land in the country, allowing farmers the right to cultivate the land, but not its property.

His nephew Carlos Lopez succeeded him in 1841 with a modernizing project that included the definitive abolition of slavery and the strengthening of the national industry by encouraging highly qualified European experts to immigrate. To Lopez is owed the approval of the country’s first republican constitution, which paradoxically granted him dictatorial powers as well (Fernández, Sánchez-Barba, 1989). Under his rule, several architecturally remarkable buildings were raised in Asuncion, as the aforementioned railway station, schools, and other public facilities employing metal structures (Masi, 2011), as well as beautiful churches that exhibit, still today, the coat of arms of the State in their façades. Several prestigious buildings appeared along the axis connecting the harbor to the railway station marking the beginning of the central area eastward expansion. Many of these buildings still exist and are well preserved today, but the most expressive of them is undoubtedly the palace built next to the harbor for the residence of a Lopez’ son, now housing the Presidency of the Republic of Paraguay.

In 1862, Carlos Lopez was succeeded by Francisco Solano López, his eldest son who had studied in London and Paris. The new president’s main interest may have been to position the country on the international stage as a modern military, economic power while maintaining the economic protectionism and internal industrial development launched by his predecessors. Lopez defended the economic independence for small countries against the largest economies of the time, displeasing especially England, whose banks were major creditors of Brazil and Argentina (Galeano, 1971). As a more or less expected consequence, the Triple Alliance War was declared jointly by Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay against Paraguay under the blessings of England, and lasted from 1864 to 1870. The war wiped out most of the country’s male population, reduced its territory to a third of its pre-war size, and destroyed its sovereignty and industrial productive capacity. Asuncion was devastated and looted, and many of its imposing buildings were destroyed during the following two-year occupation by Brazilian and Argentine armies (Rubiani and Tramontano, 2018).

The city reconstruction took place in a very diverse political environment, led by conservative local groups at the service of the winning countries. Some art déco and modern constructions from this period still remain in the Historic Centre, side by side with examples of Italian and French academicism. After a series of short liberal governments, and echoing a sad trend in the region, the 39-year long military dictatorship of General Alfredo Stroessner was installed in Paraguay in 1954, becoming the longest in the continent. In addition to consolidating among the society a feeling of fear and alienation for the state acts, the main legacy of Stroessner’s government is probably the construction of the Itaipu Binational Hydroelectric Plant in the early 1980s. Besides its obvious economic contribution to the country’s wealth production, Itaipu generated a new class of well-heeled investors and consumers, which Jorge Rubiani calls the Barons of Itaipu, and Masi (2011) describes as

“(…) an entrepreneurial bourgeoisie endowed with a false idea of progress or modernity, which seeks for its achievements other models totally alien to the time and place in which they live: an eclectic architecture, of revivals and painterly elements, which shaped much of the urban landscape of the new neighbourhoods.” (Masi, 2011, our translation)

Even though Itaipu remains nowadays the largest source of funds to finance modernization projects in the city and the country, this capital injection into the local economy from the 1980s stimulated the rise of a real estate market, which was eager for urban expansion areas, meaning cheap land and great advertising appeal. This relatively unexpected financial event was the turning point that led to the gradual abandonment of the Historic Centre. It left unfinished several high-rise buildings, stimulated the demolition of old buildings replaced by parking lots, and finally drew the profile of downtown Asuncion as we know it today (Causarano, 2012). This is how the region ceased to be interesting for the real estate market but continues to house the city’s and the country’s administration, as well as many concrete landmarks of collective memory. This brief timeline suggests that, in its nearly five hundred years of colonial and national existence, Asuncion and Paraguay never experienced a truly democratic period, even though, before the Triple Alliance War, dictators seemed to express a genuine desire to raise the poor’s living standards. Only one experience of participation was granted to them very recently, during the short presidential term of former Bishop Fernando Lugo, elected in 2008 and overthrown by conservatives in 2012.

Also included in the PlanCHA, the portion of the Historic Centre known as Chacarita stands on the strip of land between the centre and the Paraguay River, which periodically floods a part of it. From the city’s foundation, the area was settled by indigenous people, the most hostile to catechesis and integration with Spaniards, and even after the consolidation of National States in the region the river still symbolized the danger of invasions, as the route of enemy warships (Rubiani and Tramontano, 2018). It was in this emptiness, at the same time feared, despised, and avoided by the rest of the city, that the poorest settled, those who had no means of paying for housing and depended on favours from the centre’s residents. This labyrinth of passages, stairs, and winding streams has become a neighbourhood, which is now home to a population that almost doubles the number of residents of the centre’s formal portion and who have their formal or informal work in the Historic Centre.

Despite its intense dynamism, Chacarita is still a void, in many ways, due to its absence from official maps; from municipal urban policies, which do not provide for effective measures to solve the serious problems in the neighbourhood; from public security planning, which ends up encouraging the proliferation of criminal groups housed in the area; and for its role in the imagination of the city residents, who barely see it as part of the Historic Centre, as it is hidden in the river banks. And yet, in addition to several cultural events, such as theatre, graffiti, and hip-hop groups, and its famous orchestra “Sonidos de la Chacarita”, the neighbourhood is the birthplace of guarânia, an extremely popular musical genre, which is an internationally known symbol of Paraguay, a mixture of indigenous and European sonorities that sounds like a nostalgic lament.

3. PlanCHA and its strategies

Asuncion and its centre have been the subject of urban planning since at least the 1990s (Causarano, 2012). Several master plans were produced by local technicians, while some others had the advice of foreign specialists or were authored by international offices, such as Ecosistema Urbano and Jan Gehl, both in 2014. Plans have been proposed by the National Government, the Municipal Government, or by various local associations. The introductory text of the most recent of them, prepared by the City in 2018 (Asuncion, 2017, boards 4 to 8) lists twenty-two urban plans proposed in only twenty-three years. None of them has ever been implemented.

The many reasons for this phenomenon are of a technical, political, economic nature, and to discuss them would exceed the limits of this article. However, it is interesting to note that: 1. Almost all plans were submitted to national or international development institutions, to obtain non-repayable funds for the local agency that promoted it or was willing to carry it out; 2. Urban actions of a master plan scale are necessarily government initiatives, generating political prestige, which may displease political opponents; and 3. Roadway interventions stand out among the few fragments executed of some of these plans, clearly benefiting the real estate market by involving large construction companies, as in the case of the newly constructed Costanera Avenue - proposed by the 1993 Franja Costera plan - and the BRT line of the Metrobus Project, whose construction started in 2017 and was cancelled two years later.

PlanCHA differs from other plans in some crucial ways. First, it refers only to the Historic Centre and includes the Chacarita area. Second, it was conceived by the National Secretariat of Culture from the popular celebrations in the centre’s public spaces for the bicentenary of Independence, in 2011. Thus, innovatively, the plan brings urban thinking and cultural actions closer and formulates proposals of public policies simultaneously in the Urban Planning and Culture areas. In addition, like a metaplan, it envisages the gradual construction of the plan itself, through intense popular participation, based on an initial theoretical and methodological framework developed by the architects of the Ecosistema Urbano office. For this reason, instead of a conventional master plan, PlanCHA is an actions’ plan that aims to give protagonism to the residents. Such actions seek to stimulate communication between the many groups involved, bring out different conceptions of a city, and encourage the bottom-up construction of ways to make them a reality. Finally, the plan proposes to conceive and implement solutions to stop the economic and population emptying of the Historic Centre, the devaluation of its heritage wealth, and its environmental deterioration, through concrete actions, in a process planned to last for several years. It is, therefore, a master process, as one of its base documents underlines:

“The Master Plan for the Revitalization of the Historic Centre of Asuncion (PlanCHA) goes beyond a master plan (...). This ‘beyond’ is understood as a moving ‘director process’ to revitalize the historic centre. The Plan is based on a series of strategies and projects and a unit of management, articulation, and execution, which will feed on the inventiveness of citizens to regenerate the city, and on the will of state institutions (Municipal Government, National Government basically). [The state] will incorporate this creativity and regularly execute, for a long period of time, the dozens of actions and measures that outline the future of Asuncion imagined by the Plan.” (PlanCHA, 2015, p. 2, our translation)

The notions of community participation and collaboration in processes of collective construction of understandings and proposals for cities, and their implementation have been widely discussed in the field of Urbanism worldwide since at least the 1960s. While the etymology of the word ‘participate’ (lat. part + cipere) indicates a voluntary action to take part in something, the term collaborate (lat. co + laborare) supposes the collective realization of interconnected actions. Expanded and enhanced within the scope of Digital Culture and reaffirmed by citizen manifestations that became emblematic from the beginning of the 2010s (Castells, 2013), these concepts preside over the methodology adopted by PlanCHA both for the collective formulation of proposals and projects, as for its implementation, bringing together various social actors.

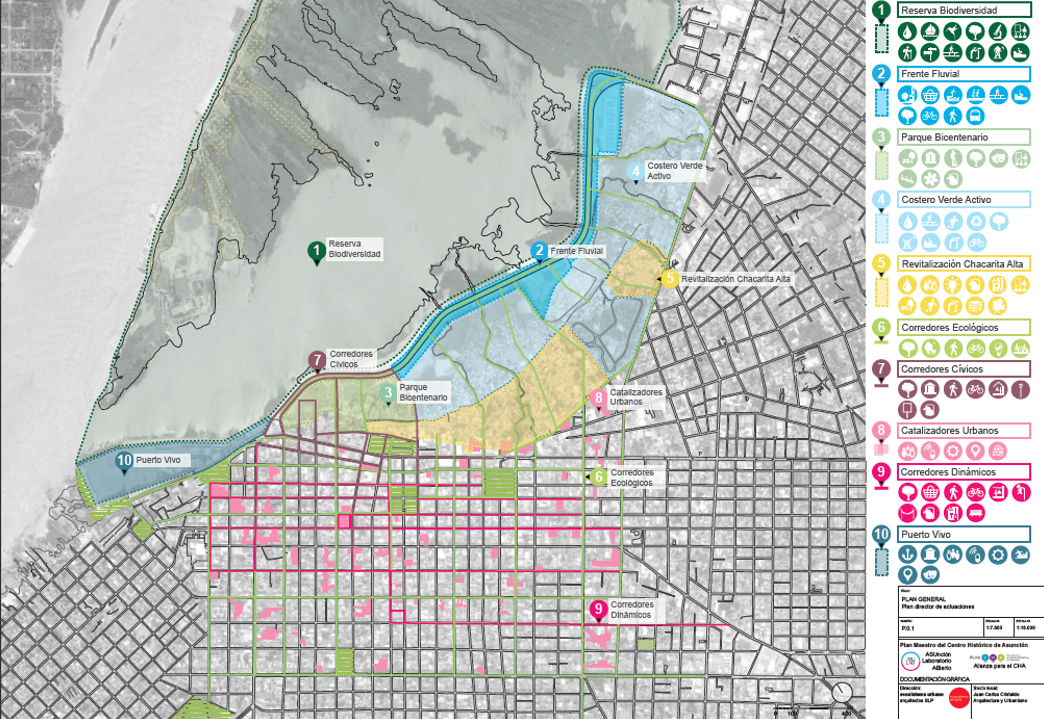

PlanCHA is based on ten specific strategies, but flexible enough to enable its progressive achievement over time. The strategies are designed in an integrated manner and imply a multitude of actions, varied in size. The actions are difficult to quantify because although some of them are proposed by the plan and are mentioned below, some are expected to emerge from proposals and demands of groups and individuals involved and to be involved. They are not intended to cover all aspects of the Historic Centre but to propose and influence critical issues connected to specific urban places, prioritizing historical, environmental, and socio-cultural topics. As the plan’s skeleton and its visible face in the urban physical space, these strategies help to conceptually interconnect different sites, seeking to guarantee the development of places with a defined character, which can function as attractors, vectors of change, and landmarks in the city (figure 2).

The strategies involve interventions designed to give visibility to the transformations undertaken in the central area (PlanCHA, 2014a). They were formulated from the study of previous plans for the city, consultations with local experts, the study of historical documents, demographic data and socioeconomic indicators, technical visits and field survey by the Spanish team in Asuncion, and the examination of good-practices across the world. In all strategies, the use of renewable resources, passive energy systems, and the recovery of buildings and structures of historic interest are a priority as far as possible. Two strategies target the environment, a third one regards the requalification of Chacarita, and the others aim to stimulate new cultural, economic, artistic, social, and administrative dynamics in connection with the area’s historical and cultural heritage. We will comment briefly below on their scopes and means, referring to the document Asunción Laboratório Abierto, Tomos 1 y 2 (PlanCHA, 2014a and 2014c). Detailed maps of each strategy are available at http://plancha.gov.py/texto-completo-del-plan/tomo-2/.

1. The Biodiversity Reserve. This strategy focuses on the Banco de San Miguel, a peninsula of riparian forest located in the Bay of Asuncion, in front of the Historic Centre. Keeping the Ecological Reserve Management Plan (Asuncion, 2016) as a main reference, it gathers actions aiming to transform the place into an ecological reserve for research, environmental education, and responsible leisure. After cleaning the area to enhance biodiversity, the Plan foresees the protection and cataloguing of the natural heritage, the promotion of tourist and educational activities aimed at preserving the area, and the construction of light infrastructures for observation and accessibility. No action regarding this strategy was carried out during PlanCHA’s two years of activity.

2. The River Front. The project mirrors the global trend of enhancing urban waterfronts, by planning the expansion and qualification of pedestrian spaces along Costanera Avenue, whose first and second stages were built between 2010 and 2019 on the banks of the Paraguay River. This strategy aims to foster spontaneous or induced cultural, commercial, sports, and leisure activities, many of them carried out during the term of PlanCHA and beyond, aiming at consolidating the democratic character of the area as a locus of sociability and expression of diverse social groups. Indeed, in a country with such a large poor population and extreme social inequality (GINI index 0.536, the highest in Latin America after Brazil. DGEEC, 2016), it makes sense to create wide public spaces for socializing. This initiative also promotes a review of the historical relationship between city residents and the river. It is noteworthy that this project can arouse lively interest in the real estate market since it allows and encourages the construction of tall mixed-use buildings along the avenue, on the strip between the road and the future Active Green Coastal (see strategy number 4). However, it is crucial to limit the buildings’ height not to compromise the effort of integrating the riverfront and the Historic Centre due to the presence of a visual barrier of too high buildings.

3. Bicentennial Park. Partially built for the Independence Bicentennial celebration in 2011, this park lies between the old port, the Presidency of the Republic Palace, and Costanera Avenue. Its construction assumed the removal of several precarious houses, and dwellers were resettled in a new housing development, some 2.5 km away on the same coast. The plan proposes to review the park’s design, in order to transform it into a strong link between the institutional buildings already installed and those to be installed in its surroundings, to make important aspects of the country’s history more readable. As we will see in strategy number 10 (Harbor Alive), once the old port is requalified in a place for the creative economy, this park will assume a central role in articulating this part of the city. As a supposed place to stay for a large number of people, and because of its location between buildings of important public institutions, the park is expected to become a wide place for cultural, civic, and artistic citizen manifestations, a reference for the whole city, in the heart of the Historic Centre.

4. Active Green Coastal. This strategy is articulated with those of number 2 (The River Front) and 5 (Revitalization of Chacarita Alta). It focuses on the vast marshland located between Costanera Avenue and the so-called Chacarita Alta, or Upper Chacarita, which is the part of the Chacarita neighbourhood above the flood level, as shown in figure 1. In this area, an extensive green urban infrastructure is expected to be shaped, with processes of natural water purification integrating the landscape. To make this strategy effective, it is mandatory to remove the existing precarious shelters, and relocate their residents who face a situation of extreme social vulnerability. The plan suggests resettling them in new buildings along the waterfront, or in currently abandoned multi-floor buildings in the Historic Centre, after recovery operations. The plan also proposes the construction of a lightweight infrastructure that can be playful, sporting spaces, or urban gardens, consistent with its character of a flood zone, due to the periodic flooding of the Paraguay River. However, this is undoubtedly one of PlanCHA’s most controversial strategies and probably to a great extent responsible for campaigns to discredit the plan by politicians and real estate agents, as it targets the largest empty area still available next to the Historic Centre. Great political support is given to the Franja Costera plan (1993), which proposes the grounding of the area and its use for private real estate actions, ignoring springs, ponds, streams, and the river flood regime.

5. Revitalization of Chacarita Alta. This strategy proposes the upper, consolidated part of Chacarita to be the object of various interventions, having as main references the requalification project of the old slum of Loma San Jerónimo, also in the Historical Centre of Asuncion, and Brazilian slum recovery programs. Planned actions include Chacarita in cultural circuits in noticeable neighbourhoods, through two main procedures: to stimulate participatory actions of beautification and urban art aimed to create meaningful places, and to forge structures of income generation and improvement of the residents’ training and education. PlanCHA carried out several actions in the neighbourhood, such as workshops and open hearings aiming to encourage residents to express their demands and suggestions, besides the remarkable and meticulous drone-aided mapping of the totality of houses, paths, and water bodies in the area, registered in GIS. Completed after the plan was already suspended, this mapping was possible due to the voluntary collaboration of dozens of technicians and students from the National University of Asuncion (Cristaldo and Britez, 2018). Such actions and the continuous work of several associations and NGOs subsidize the organization of various cultural and sports projects with the local population. There is no doubt that the great challenge of this strategy is to integrate Chacarita with the rest of the centre and the city, not only by promoting the physical approach of residents but making the neighbourhood an attractive place for visitors and also potential future higher-income inhabitants.

6. Ecological Corridors. A threefold objective presides over this strategy: to extend the presence of vegetation from the Active Green Coast (strategy number 4) to selected streets in the Historic Centre; to strengthen the contact of central area goers and residents with vegetation and elements that stimulate reflection on the environment; and to promote collaborative actions to implement ideas related to these topics. The strategy thus seeks to connect the notion of praxis as the integration between practice and reflection, to the field of urbanism and participatory interventions. The suggested collective actions - many of them carried out by ASULab (see item 4. A necessary sphere for mediation) in collaboration with cultural collectives, university students, and the community - include to organize sessions for the spontaneous planting of trees, to occupy public parking spaces with plants and furniture, to produce vegetated walls and works of urban art that allude to environmental issues, to paint unplanned bicycle lanes on the street floor, to make temporary pedestrian stretches of streets, among many others. An interesting side effect of this strategy can be the strengthening of local groups and collectives concerned with environmental issues, which will be able to make visible their agendas by carrying out actions in the Historic Centre. Also part of this strategy is the study to implement the practice of green roofs in the central area, helping reduce the thermal anomaly known as heat islands, common in dense urban centres.

7. Civic corridors. This strategy aims to physically signal the Historic Centre by using expressive historic and administration buildings as beacons on tracks that seek to connect the city’s and the country’s history to its current daily life. The system of beacons and itineraries would produce a temporal layer, juxtaposed to the current grid of the city and its own dynamics. In the activities included in this strategy, there is a unique opportunity for collective historical reconstruction and public debate about which assets should be highlighted in the urban landscape. In other words, the strategy allows us to review which memories witnessed by these buildings the society understands must be permanently preserved, which values of the official past really should not be forgotten, and which other memories, perhaps concealed over time by different interests, should now be rescued. Light and sound interventions on buildings and monuments, workshops for training and discussion on the cultural heritage of the city and the country, and the creation of interactive digital information systems on history and its concrete landmarks of memory are examples of actions. The plan hoped to encourage various sectors of society to discuss guidelines that would lead to the definition of policies for the buildings’ preservation and use. The National Secretary of Culture initiated several actions aiming at revaluing this heritage during the 2011 celebrations to draw attention to buildings of historical interest, often in a state of neglect, poor conservation, or loss of original features.

8. Urban Catalysts. Tall buildings housing a wide variety of uses in addition to dwellings, to be built on now-vacant lots or in degraded areas to be reactivated, are what the plan designates as urban catalysts. However, they should rather be installed in some of the many unused buildings, promoting their rehabilitation and reconversion. It is expected that creating a layer of equidistant multipurpose buildings by controlling their location in the urban fabric can ensure a relatively homogeneous spatial distribution of places with high density, and a great mix of economic and social activities. Besides, combining several functions in the same building, such as offices, shops, services, leisure, and housing, can contribute to densify the centre and reverse the city’s zoning logic. Finally, this strategy also aims to increase the number of publicly-accessible rooftops, which became quite popular in Asuncion in recent years, with the opening of several rooftop bars and restaurants. The Urban Catalysts go further, considering that some roofs could become real public squares in height, privately owned, state-supported, but freely accessible to the public. This action reinforces the proposal to create green roofs, suggested in strategy number 6, Ecological Corridors. The design of one of these buildings for three adjacent plots currently vacant in the centre ranges among the products PlanCHA delivered to the Ministry of Housing. ASULab developed the building’s design based on the results of a public debate held via a smartphone application and online platform on the expectations of city residents about living in the Historic Centre.

9. Dynamic Corridors. Parallel to the historic east-west axis, the streets chosen to become dynamic corridors lie in central consolidated commercial areas. They are supposed to connect business locations, cultural buildings, squares, and the Urban Catalyst system (see strategy number 8). The purpose of these corridors is to requalify commercial activities as vectors of urban animation and include street vendors who, in the historic centre of Asuncion, usually sell traditional and indigenous products. Today, even on the main commercial streets, the closed doors of many empty business locations have an unpleasant impact on the street dynamism. This strategy proposes to merge commercial activity with cultural actions, thus stimulating varied activities 24 hours a day, by creating, for example, public parklets housing both extensions of shops and playful, relaxing urban furniture. The idea of stimulating some activities during the night, when most commercial places are closed, also seeks to make the experience in the centre less insecure. It reverberates principles defended by Jane Jacobs when she relates the notion of 2eyes on the street” with the need for the presence of people on the sidewalks (Jacobs, 1961).

10. Harbor Alive. Deactivated in late 2013 and as large as 24 hectares, the port of Asuncion is the largest vacant area above the flood level in the Historic Centre. Previous plans have already earmarked this plot as the future location of the National Government’s administrative buildings, and also designated places for cultural and leisure activities. PlanCHA proposes to expand a small public park nearby, created in 2011 to host events to celebrate the Bicentennial of Independence, and to preserve only the main building of the Customs and three neighbouring warehouses, hosting commercial and cultural activities. The plan maintains the port’s use for recreational and sporting purposes only, houses the Metrobus Project’s BRT terminal, cleans and requalifies the Jaen stream, and extends the Costanera Avenue promenade (see strategy number 2, River Front) as a pedestrian connection between converted historical buildings. Lying at the centre’s west end, this strategy treats the port as an urban finishing of the Civic, Ecological, and Dynamic corridors and a new pole of entertainment and leisure for the entire population of the Metropolitan Region, seeking to boost new economic structures in the district.

Each strategy comprises a specific and detailed action plan, totalling plenty of actions described in the plan’s public documents (PlanCHA, 2014a, 2014b, and 2014c) such as workshops, collaborative mapping, exhibitions, public debates, community surveys through digital platforms and smartphone applications, the production of educational school kits, spontaneous and scheduled artistic interventions in public places, and so on. Their natures, procedures, and objectives are quite varied. They stem from partnerships with cultural institutes, public authorities, universities, and Third Sector organisations, and always target citizen participation through collaborative procedures. Some actions carried out ephemeral or lasting interventions in the physical space; other actions explored the use of digital remote communication means, and others led to discovering and understanding historical aspects of the centre. The relevance of these actions lies in the effort to include the various sectors of society interested in the Historic Centre renovation, inviting them to express, in different ways, their wishes, projects, critical readings, and expectations.

4. A necessary sphere for mediation

To manage the entire process, the plan created ASULab - Asunción Laboratório Abierto (Asuncion Open Lab), bringing together professionals in the areas of Architecture, Urbanism, Economics, Environmental Engineering, Administration, Communications, and Human Ecology, in addition to specific consultants. As one of its documents describes,

“Asulab is an interface between institutional management and citizen impulse. It is a place to develop official planning and an open place for any person or group to promote a new regenerative initiative or take part in actions in progress. It is also expected to work as a connection point with private agents able to financially support the centre regeneration through a project development.” (PlanCHA, 2014a, page 5, our translation)

Indeed, the main challenge was to create an entity with the legitimacy to act in the entire scope of the plan, capable of promoting trust between the various actors, establishing binding agreements, boosting projects, and supporting both institutional and citizen initiatives and their hybrids. But examining the PlanCHA documents, it is clear that expectations regarding ASULab were huge. The wide range of the Lab’s duties involved, for instance, all mediation and negotiation with the myriad of decision-makers and society representatives, the definition of legal frameworks for implementing all proposed interventions considering specific legislation, the mastery of the requirements of public and private real estate financing programs, mapping and documenting the entire Historic Centre, the production of architectural and urban design, the organisation and management of face-to-face and remote means of public consultation and debate, the production of open access cultural and artistic events, the critical examination of all previous urban plans, among others. Such a gigantic task required a much larger team, more significant physical and financial means, and people with great influence in the sectors of society involved in the plan’s implementation, both in the national and municipal political spheres. The absence of these conditions was pointed out by several interviewees as one of the main reasons for the plan’s failure.

However, much of this huge task was carried out by only nine professionals, five interns and five assistants (Cristaldo and Torreani, 2017). Among their many products, we highlight the remarkable work of mapping and documenting historic, empty, or underused buildings across the central area. Photos, descriptions, and specific measurements were produced collaboratively and at low cost by ninety volunteer students, shaping a valuable, unprecedented collection in Paraguay. Also noteworthy are the detailed studies relating existing housing funding programs to their legal bases, aiming to make possible the housing use of underused or vacant buildings and others to be built in the Historic Centre, to motivate potential investors.

Finally, but not less relevant, we must highlight the methodological contribution of the ASULab team by putting into practice and adapting to the Asuncion context the principles of action outlined by Ecosistema Urbano. Once the training sessions for which the Madrid-based office was hired after winning the competition ended, it was up to the Paraguayan team to devise ways to encourage dialogues between local groups and social actors. Despite its limitations, the ASULab team faced the challenge of designing and implementing solutions to the many daily-arising problems stemming from this practice. One of the team’s most noteworthy products was precisely a well-documented modus operandi, to be used in other cities and similar situations.

Two ASULab’s products are of particular interest for urban intervention practices in general, and for research on digital means and social technologies: the Activación Urbana mobile application and the ASUMap online platform. The application was produced by a team of computer scientists, which won a public competition sponsored by ASULab. Designed for the Android operating system, Activación Urbana allowed users to interactively obtain information about historic buildings and places in the centre. Much more complex is the ASUMap platform (http://www.asumap.com), whose design feeds on the good results of the use of similar platforms by countless local governments, including Madrid’s, Barcelona’s, Paris’, and London’s.

Ecosistema Urbano developed the ASUMap platform by using LocalIn’s open-source computational code, a WordPress theme which allows its relatively easy replication in future projects. It is an online, open-source digital environment targeting all Asuncion Metropolitan Region residents, especially those who visit and live in the Historic Centre. It aims at organising and stimulating citizen participation in debates about the centre transformation, being at the same time a repository of ideas, documents, and proposals, and a place for discussing and debating within decision-making processes of urban intervention. The platform allows users to geolocate messages, weblinks and photos on the city map through the filters “Institutional Initiatives” and “Citizens Initiatives”. Entries can be classified according to five categories: Ideas, Initiatives in Progress, Proposed Initiatives, Activities and Events, and Memorabilia.

A special section organizes and presents the repository for the Historic Centre mapping, formerly available at http://www.asumap.com/dateo. It was designed to be continuously fed by the community, aiming to expand and update the available information. Since the Google Street View tool is not enabled in Paraguay, ASUMap was the only online platform that offered Internet viewing of the streets and buildings in the Historic Centre. As, unfortunately, access to ASUMap was disabled in 2019, we provide the link to the PlanCHA website (http://plancha.gov.py/plan-cha/), which contains part of the information once available on the platform.

5. PlanCHA suspended

After several attempts by the ASULab team to ensure the continuity of PlanCHA’s development, it was definitely interrupted in 2017. We will briefly examine some administrative, political, and socio-economic reasons that seem to explain such interruption, considering the testimonies gathered in Asuncion, the ASULab final reports, academic and official documents.

5.1. Administrative reasons

- The absence of a metropolitan administrative dimension between the national and municipal spheres, and the disconnection between the existing spheres, as emphasized by interviewees linked to the Government and ASULab. Asuncion is an autonomous municipality, administered as a Capital District and not formally integrated into any Department of the country. Several PlanCHA decisions required the difficult endorsement of other municipalities of the Metropolitan Region. One of the many examples is the very idea of “bringing back to the centre” part of the population that settled over the decades in neighbouring cities. If, on the one hand, this return would probably reinvigorate the CHA, it could cause, on the other hand, a considerable loss of dwellers and commercial activities to several municipalities.

- The inexistence of an governing body like an Institute or Public Agency of Urbanism responsible for the capital city, with powers to implement decisions in an agile and effective way. If this body existed, it would have probably inhibited the production (and the non-implementation) of so many plans for the city, and would naturally house PlanCHA, affording it greater political weight.

- The lack of definition of a legal framework to legitimize the ASULab operation, making the cooperation between the Asuncion City Hall, the Metropolitan Region, and the National Government official. Such legal support would provide ASULab with decision-making capacity, possibly making it the embryo of the aforementioned public agency.

5.2. Political reasons

- A new municipal administration was elected in 2016, whose political party and ideology differed from those of the National Government. It was the feeling of some interviewees that the new leaders were not interested in embracing a plan with the mark of their political opponents, despite identifying themselves with some of PlanCHA’s proposals. ASU Viva is the current city plan, which was elaborated by those who were elected in 2016. It focuses on the entire city and not just the Historic Centre and disregards results, recommendations, and above all, PlanCHA’s participatory methodology.

- As the population and economic activity increased in other cities within the Metropolitan Region, there was a change in the political weight of the capital city, emphasized by three respondents, which culminated in the loss of two seats of deputies. In the absence of a metropolitan administrative body, it is in the National Congress that many of the negotiations on urban and regional issues take place, and this clash is guided by the interests of private groups that finance the election campaigns of several parliamentarians. Housed in a secretariat of less political weight - that of Culture -, PlanCHA ultimately lacked parliamentarians and/or private groups that would defend its postulations in this scene.

- PlanCHA was created by a group of progressive academics, artists, and intellectuals linked to the Secretary of Culture of a conservative national government. The house probably ceased to support the plan when the distance between its project of a city and the one proposed by PlanCHA became obvious, as the plan evolved. This reason was evident at the end of the sectoral meeting between the ASULab team and real estate agents within the scope of PlanCHA, according to participants.

- As we were told by more than one interviewee linked to the Government’ sphere, some associations and groups involved in the making of previous plans have put pressure on government bodies not to implement the plan, asking to be commissioned to carry out a new plan, as they did not feel like protagonists in PlanCHA. One association that withdrew from the plan, and started opposing it, was subsequently appointed by the National Government - after PlanCHA interruption - to organize a closed competition aiming at requalifying the harbor area. The winning proposal is under construction in Asuncion at the time of writing this article.

- Since PlanCHA was suspended, both the National and Municipal Government have already developed new plans that add political prestige, attract non-repayable financing, and pave the way for new public-private partnerships, especially with real estate agents.

5.3. Socio-economic reasons

- Paraguayan society as a whole shows a rather limited political culture since the country has always been governed in a top-down, almost arbitrary way by conservative politicians of the wealthiest classes. This tradition probably makes it difficult to visualize other possible political experiences, especially those involving collective construction. The limited interest shown by the population in participatory processes can thus be partially explained by their historical lack of citizen participation in public decision-making processes.

- The replies of Chacarita interviewees reveal they hardly believe that the implementation of PlanCHA would bring them benefits. Despite their efforts, the plan’s authors and executors are still seen by many as agents of urban and social policies that, in the end, tend to exclude the poorest.

- The number of participants in the sectoral discussion meetings, as described in several PlanCHA documents, seems very small compared to the entire city’s population. In many cases, most of the participants were representatives or have been invited by the organizers, perhaps with little political strength or weak representation in their communities and sectors. Likewise, the number of meetings seems to have been insufficient to build durable and comprehensive agreements and consensus. For example, several meetings were held in Chacarita with local leaders while only one brought together real estate agents and property owners and lasted less than two and a half hours. They are both documented in Volume 3 of the final ASULab reports (PlanCHA, 2014b).

- There was a clear disinterest in PlanCHA by real estate investors. They are potential and relevant partners for all urban intervention but, in Asuncion, they seek rather a low-cost land far from the centre, preferring to build tall buildings on empty land. Such practices are directly opposed to the plan’s recommendations to densify the centre. Besides, the city lacks incentives in the form of exemptions, counterparts, or better financing conditions for investors and builders to agree to face the difficulties of recovering existing buildings or even to build in fragmented and irregular lots located along the narrow streets of the Historic Centre.

- Data on economic activities making up the GDP of the city, the metropolitan region, and the country, compared to the ways as part of this capital is usually invested in the production of urban space, suggest that is not enough demand, neither in Asuncion, nor in Paraguay, to support the creation of so many areas for residential and commercial use in the Historic Centre, as proposed by PlanCHA. Strategies such as the tall buildings of the River Front and Urban Catalysts, and even the shopping mall of Harbor Alive, demand a level of investment and consumption that the local society may not be able to afford yet.

- Finally, designed for all residents and users of the centre as a means of information and debate, the online platform ASUMap and the mobile application Activación Urbana were accessed by about two hundred people each, according to ASULab members. This figure looks far below what could be expected, considering that 86.9% of the country’s urban population had access to the Internet at the time (Paraguay, 2017). Official support to publicize and encourage the use of these means has been insufficient, coupled with the lack of habit of participating in public debates, and the community’s little confidence that their suggestions would be implemented.

6. Conclusions

PlanCHA’s experience in one of the poorest and most unequal countries in South America, and with no tradition of popular political participation, cannot go unnoticed. Indeed, the brief examination offered in this article shows the potential and limits of this experience. There are many lessons to be learned from Asuncion. In our conclusions, we do not intend to offer guidance derived from PlanCHA for future urban plans, as each city or urban fragment is a complex system with its particular interrelationships. However, we will emphasize some aspects of the methodology resulting from the Asuncion experience, suggesting preliminary recommendations for future projects.

First of all, one should never forget the central role played by political will, which made possible the plan’s formulation and partial accomplishment, and also decreed its interruption and deactivation. Second, PlanCHA constituted an extremely organized, comprehensive, and inclusive methodological framework, which can be used in similar projects to encourage communities to collaboratively rethink their cities or neighbourhoods. The idea of collaboration the plan expresses prioritizes the dialogue between the various social actors, aiming at a praxis that simultaneously stimulates the sharing of reflections and practical actions.

Moreover, its development does not require excessive public funds if compared to the costs of implementing classic master plans. In plans like PlanCHA, public bodies are expected to play the role of mediators, stimulators, and facilitators of collective formulation that will lead to concrete yet simple actions in areas under their responsibility, such as Culture, Education, Environment, and Public Works. Provided they prioritize the public interest, partnerships with the private sector, but also with public universities, associations, and collectivities, in addition to national or international non-repayable financing, allow us to glimpse promising paths for cities transformation.

The plan also produced a rich and complex methodology of action, combining face-to-face and digitally mediated procedures, which can be applied in other cities and similar urban situations, especially in the Global South. Its extremely thorough documentation remains publicly available on the project’s website. Through such methodology, the plan managed to successfully test the promotion of dialogues between sectors of society that otherwise scarcely communicate. PlanCHA’s actions resulted in projects still underway in the centre of Asuncion, such as Temporary Urbanism initiatives that continue to draw the city interest to the region. The Asuncion National University has also benefited from the consolidation of the Centro de Investigación Desarrollo e Innovación - CIDI (https://cidifadauna.com/), a centre of excellence in urban and digital research and projects, which is mainly composed of former ASULab members.

Needless to say that the plan’s cancellation generated great disappointment in those groups most involved in its implementation. In addition to the difficulty in dealing with so many different topics and urban issues, these groups were barely able to communicate with each other in debates of ideas greatly expected in such plans. Perhaps the main objective of the plan and ASULab should have been to build solid participatory foundations for communication and debate of ideas about the city. But on these bases will come to anchor means that need to be sufficiently supported institutionally and well understood by the community, so they can act as channels of approximation between social groups now segregated and stimulate the slow yet steady construction of citizen consciousness of participation and collaboration.