Introduction

This research seeks to relate some of the processes that led to consider, within the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM), the inclusion of the concept of community and the successive incorporation of the settlers to the architectural project, by showing a context of references, reverberations and interactions around the subject.

The manuscript is structured in three parts: first, a historical approach to the matter is made, in which the proximity of the architect to a certain social field is described, characterized by its immediacy to the holders of the economic and political power in each historical period; secondly, the processes of dissension inside the CIAM , when various interlocutors (professionals belonging to the critical wing of the so-called international style) demanded the incorporation of the communities into the project; thirdly, the association of all those processes in Peru, taking as a starting point the vision of the culturalist / humanist designers who inspired the young architects of Team X and also the English architect John Turner, who was invited to investigate various processes of urban occupation on the outskirts of Lima and Arequipa and became a key figure between the so-called north and global south.

In the urban sphere, it was a period characterized by rich discussions, promoted by a whole generation of architects and critics with countercultural / anti-hegemonic ideas , validated in their time with the incorporation of theories of the Scottish biologist Patrick Geddes, with the consent of professionals of recognized anarchist militancy and actively incorporated in the CIAMs.

This review is also presented to promote to the professional educational-training field the consideration of spaces not disputed by the real estate market as an area of professional performance, with the intention to strengthen the self-management of the settlers, under the advice of technical groups that support those initiatives.

Those experiences were born within the community and in defense of the right of all the inhabitants of the polis to make themselves a space in the city, in opposition to the conception of the urban space as a priority to the land market and real estate speculation, by demanding the right to use the spaces of the city and their appropriation as a common good for all.

Certainly, there may be other perspectives to resolve the object with the inclusion of other characters and other conceptual frameworks, but the work presented below is the product of the chosen path, which seeks above all to think over the incorporation of these practices, its origins and implications in Peru.

The elitist position of the architect

To understand the matter, a historical approach leads to establish some gears about the architect's approach to communities, an unprecedented position since, historically, the professional figure was directly linked to the relationship with the power groups of each era.

But where does this elitist position of the architect come from?

With the establishment of the liberal mode of architectural production, in the Renaissance - parallel to the establishment of the capitalist mode of production - the architect became a professional linked to the elites, directly associated to the great power figures: the church, the state and the bourgeoisie (Gnecco, 1983).

The association with the powerful ones of the time was what allowed the evolution of the practice of a “master builder” or “manual worker” to that of an artist and intellectual worker who would house the knowledge of specialized practices that would lead to the formation of a discipline with specific information.

Synthesizing Bourdieu (2004), “a field” that involves “the transformation of space by human work” - definition of architecture proposed by Kapp, Baltazar and Morado (2008, p. 9) which, from the point of view of the liberal doctrine, should include the complement: regulated and of interest to the spheres of power of the time. When the professional field of activity is historically analyzed, it can be verified that it does not involve the entirety of the space produced by man, but the portion of interest - the field - of the spheres of power linked to professional practice of liberal nature: “the very small portions of man-made space historically addressed by this specialized knowledge” (Kapp, Baltazar & Morado, 2008, p. 8).

What about the largest portion of the space that has not been addressed by the field?

It is what has historically been resolved autonomously by users, who, despite composing most of the space modified by the man, are not endorsed by that professional field that responds to the interests of powerful minorities.

About the evolution of the professional field of activity, from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance period, the work of the Australian architect Garry Stevens (2002) analyzes from a bourdian point of view the professional practice and categorically clarifies this trance:

(…) Through the Middle Ages, the architect remained largely anonymous (…) In the Renaissance, architects were able to turn the tables on their patrons by displacing the charismatic properties of building into an abstract and theoretical discourse about architecture. The passage of the occupation into an increasingly academic and official phase began in the late Baroque in France, where the monarch increasingly controlled monumental building programs. The establishment of the Royal Academy of Architecture in France allowed architects to affirm official control over the symbolic and aesthetic dimensions of architecture. After a brief dissolution during the Revolution, it re-emerged as the École des Beaux-Arts, thus carrying the conception of the architect’s role as a specialist in the elaboration of stylistic codes (…) Stevens, 2002

With the division of intellectual and manual labor, the architect becomes a specialist in symbolic and aesthetic matters proper to the profession, developing an architectural language that becomes personal and non-transferable. During the transition to the industrial period, he had to face various situations. First, the need to diversify these codes and symbols to adapt them to the requirements that the new industrial period demanded (factories, warehouses, railway stations) that the classical tradition did not handle as fundamental typologies. Secondly, to justify the prevalence of professional practice against the competence of engineers in the execution of buildings. Third, to encompass a process common to many other occupations: the professionalization of the role to define standardized competences for the rest of the union that academic teaching and degrees endorsed (Stevens, 2002).

In translated words of Kapp (2005):

The idea that every construction should be preceded by technical projects is relatively recent in Western culture. Even after the Renaissance, when the figure of an architect emerges, who conceives and designs what will be done on the construction site and who understands his own work as an intellectual activity, superior to the manual work of construction, most of the human space continues to be produced without this specialized knowledge (…). Kapp, 2005

As the practice is linked to power figures and the creation of symbols to exalt that power, understood as “extraordinary” elements, the “ordinary” element typologies such as dwellings that up to that moment were produced by users and master builders based on the experience and repetition of building codes of the time, were not considered. Even after the adoption of the technical project as a form of graphic representation of those power symbols, until industrialization entered, most of the space was developed without specialized knowledge, just at the time when part of that field of professional action gradually incorporated some living spaces intended to shelter the working population (Kapp, 2005).

The Modern Movement (1928-1959) that arises from the association of technical, social and cultural changes linked to industrialization, leads to a period of rationalization of the classical aesthetic codes. It would not be wrong to affirm that its ideology rescues values inherited from the Renaissance tradition regarding three points: 1) the notion of work, understood as a closed object of finite development without the possibility of alterations in time; 2) authorship of the work - the original object created by the qualified technician who knows it better than the user who will inhabit it - as opposed to autonomous collective work and the technique provided by artisan work; 3) the separation between the user - who comes to be understood as a passive subject of the project - and the architect, the specialist technician who assumes the role of a demiurge who is capable of defining the way of living of individuals and their relationship with the space (Bastos, 2007).

In the first CIAM, held in La Sarraz - Switzerland, in 1928, the first of a series of declarations was made that would come a posteriori, in which the parameters to be followed by the modern ideology are dictated. In the following section of that statement, the direct relationship between the architectural project and the economic system in general is outlined:

(…) 4. The most efficient method of production is that which arises from rationalization and standardization. Rationalization and standardization act directly on working methods both in modern architecture (conception) and in the building industry (realization). 5. Rationalization and standardization react in a threefold manner: (a) they demand of architecture conceptions leading to simplification of working methods on the site and in the factory; (b) they mean for building firms a reduction in the skilled labour force; they lead to the employment of less specialized labour working under the direction of highly skilled technicians; (c) they expect from the consumer (that is to say the customer who orders the house in which he will live) a revision of his demands in the direction of a readjustment to the new conditions of social life. Such a revision will be manifested in the reduction of certain individual needs henceforth devoid of real justification; the benefits of this reduction will foster the maximum satisfaction of the needs of the greatest number, which are at present restricted. 6. Following the dissolution of the guilds, the collapse of the class of skilled craftsmen is an accomplished fact, The inescapable consequence of the development of the machine has led to industrial methods of production different from and often opposed to those of the craftsmen, Until recently, thanks to the teaching of the academies, the architectural conception has been inspired chiefly by the methods of craftsmen and not by the new industrial methods. This contradiction explains the profound disorganization of the art of building. 7. It is urgently necessary for architecture, abandoning the outmoded conceptions connected with the class of craftsmen, henceforth to rely upon the present realities of industrial technology, even though such an attitude must perforce lead to products fundamentally different from those of past epochs. (…) CIAM, 1928

Certain points are evident: 1) the defense of methods based on the rationalization and standardization of construction systems in the formulation of the project: methods that the intellectual worker adapts to the language of the Modern Movement (points 4 and 5) ; 2) the discipline responds to the designs of the industrial economic system, by dispensing workers with the know-how of artisan techniques who are replaced by low-level workers over the leadership of technicians, deepening the division of manual and intellectual labor applied to the management of works (point 5b); 3) the conception of the user as a consumer and client, who must adhere to “the new conditions of social life” imposed by the Modern Movement: a radical change in the imaginary of the user, regarding the conception of the living space adapted to the propositions of industrial logic (see point 5.c) and 4) the suppression of artisan techniques linked to construction, which the Modern Movement assumes as overcome after the dissolution of the guilds of builders in force since the Middle Ages, in favor of the prevalence of construction methods linked to the development of industrial technology (points 6 and 7).

This recession of the artisan techniques that the Modern Movement promulgated through the CIAMs, had its counterpart on other fronts that sought the reunion and protection of artisan methods. In 1919, Walter Gropius in the Bauhaus made a manifesto on this matter:

(…) The ultimate aim of all visual arts is the complete building! To embellish buildings was once the noblest function of the fine arts; they were the indispensable components of great architecture. Today the arts exist in isolation, from which they can be rescued only through the conscious, co-operative effort of all craftsmen. (…) Architects, sculptors, painters, we all must return to the crafts! For art is not a 'profession', There is no essential difference between the artist and the craftsman. Gropius, 1919

This passage is an example of the disputes that marked that period, as a part of the discussions within the CIAMs, with figures such as Giancarlo de Carlo, who held a critical position regarding the resources of objectivity and subjectivity in the praxis . De Carlo identifies the objective processes of the Bauhaus school in its first stage (1919-1923) and the resources of subjectivity with Le Corbusier's practice, criticisms that bring him closer to the new generations of architects attending the CIAMs (Barone & Dobry, 2004).

Processes of rupture

The Modern Movement meant a breakpoint with historicist techniques to make way for an own language, devoid of ornament and under a logic of dependence on industrial capitalism. Within this bosom of defense of the liberal architect, other processes of rupture emerge to that logic of understanding the praxis, leading, 28 years after the La Sarraz Declaration, to the culmination of a period that influenced and forever changed the way of understanding the professional practice. Recalling Tafuri (1976, p. 190), “(...) the fate of capitalist society is not at all extraneous to architectural design. The ideology of design is just as essential to the integration of modern capitalism (...)”, that in the industrialized world would depend less and less on artisanal work and on the opposite, on methods of rationalization and standardization of the constructive process.

The ideology of the Modern Movement would even establish closed ties with the despotic structures of the time , to correspond to the notions of hierarchy and a new social order resulting from the historical moment, assuming the readaptation of the collectivity to the new conditions of collective life that impose themselves with these project paradigms (Frampton, 2003).

Within these discussions, a group of architects, belonging to the youngest fraction of the CIAM, were strongly influenced by the ideas of a multifaceted character, with multidisciplinary training: Patrick Geddes. They became interested in the idea of an indissoluble nexus that is established between the community, as an inhabitant of the place and the project (Welter, 2002, p. 96). In this sense, Geddes promulgated an urban planning made from the holistic knowledge of the city and the region, especially of the history and of the changes caused by human activities (Herzog, 2013, p. 49).

Patrick Geddes studied from an evolutionary point of view the transformations of human communities. He was influenced by Huxley's Darwinism in his higher education, and Le Play's social geography , as a reference to develop his well-known Valley Section. In this model, he establishes differentiations between the territory and labor division, from mountainous areas down to the sea indicating different occupations (miners, ligneurs, farmers, pastors, peasants, fishermen) living in villages, each one with its own family structure and popular culture that contributed to the urban evolution (Keulartz, 2006).

He is usually recognized as a “pioneer” of several concepts in the urban area, such as “conurbation” (the union of several cities) and other derived concepts: “megalopolis”, “region city”, “metropoli”, “metropolitan region” (Nunes, 2019). For him, every urban studio must consider the existing data inherent to topography, history, the present situation of the population, occupations, salaries, family presuppositions and the level of schooling of each community.

The gedessian approach harnesses an emphasis on the indisputable association of sociological research in the urban context. Part of these proposals were inspired by the anarchist ideas of Peter Kropotkin (with whom he shared a common friendship ) regarding the cooperation between the beings (mutualism), in opposition to the competition for survival as a way of life (Keulartz, 2006).

As a result of accepting the British administration's invitation to India, Patrick Geddes carried out several urban planning proposals for different Indian cities (1915-1925) based on what he called conservative surgery , a model that diverged from the sanitizing bulldozer policy , that advocated for the importance of conserving some historical places and the participation of the citizens in making decisions. He promoted the Cities and Town Planning Exhibition in 1911, with the aim that people had full participation in the construction of their city, prior survey of comprehensive data about the place (Figure 1). Not surprisingly, he is considered “the forerunner to the participatory process in urban planning and design” (Herzog, 2013, p. 49).

In the same period, he also carried out several projects in Palestine (responding to the call of Zionist organizations) which in the urban sphere includes the centralization of urban functions in specific and accessible areas, through rehabilitation policies and the settlement of suburban areas (Hysler-Rubin, 2011). The Tel Aviv renovation plan adopted by the municipality of this city was the only Geddes project applied in its entirety following his indications .

Lewis Mumford (1895-1990) first met Patrick Geddes work in 1914 when he was a student at NY City College . They shared the belief in cities as autonomous entities, with sociological, political and economic powers that transcend as political units within their territorial spheres, beyond their defined borders (Keulartz, 2006). In 1940 the Catalan architect, linked to the CIAM, Josep Lluís Sert commissioned him to introduce the book Can Our Cities Survive?, with the aim of spreading the Athens Letter among American architects, a commission that he rejected when establishing criticisms of the four main functions that, according to the Modern Movement, all urban planning must consider:

(...) The four functions of the city do not seem to me to adequately cover the terrain of city planning: housing, work, recreation and transportation are important. But what about the political, educational and cultural functions of the city? (...) The organs of political and cultural association are, from my point of view, the distinctive signs of the city: without them, there is only one urban mass (...) Mumford, 2000

On these considerations, already at the eighth CIAM, the differences between the group of younger architects attending the congress and the generations of the first congresses began to be marked, with a series of questions that sought to overcome the rigidity of the rationalist model.

The legacy of Patrick Geddes has great repercussion for the young architects who formed the CIAM X, and particularly to Mumford and John Turner, who is influenced by geddesian ideas when attending courses for returned soldiers from the Second World War, taught by the urban planner Jacqueline Tyrwhitt (1905-1983) who was commissioned to form a major cohort that would promulgate future ideas for habitat solutions worldwide (Figure 2) (Shoshkes, 2016).

http://thetorontoschool.ca/jaqueline-tyrwhitt/

Source: Figure 2: Jacqueline Tyrwhitt, a great influence for John Turner

Tyrwhitt was a great researcher of Patrick Geddes’ theories and also a figure of great influence for John Turner and advocate at CIAM meetings for the importance of incorporating communities’ activities, one of her arguments in the discussions on the core of the cities was: “The core as an (...) expression of the collective mind and spirit of the community (...)” (Welter, 2002, p. 103).

The British group MARS (British section of CIAM, with Jacqueline Tyrwhitt as one of its initial representatives, and involved with modernist proposals in the UK) proposed to study the core of the cities on five community scales that gave life to the urban space: 1) the town; 2) the neighbourhood; 3) the city or urban sector; 4) the city; 5) the metropolis. The primary generation made up of Le Corbusier intended to discuss housing as the primary urban function, but the group of younger architects considered the discussion of social relations generated from the design of urban space to be essential (Welter, 2002, p. 103).

This vision was shared between the MARS group (represented by Peter and Alison Smithson) and the CIAM group of young architects about the importance of considering the notion of community in urban planning.

Giancarlo De Carlo was invited to join the Italian CIAM group by Ernesto Rogers in 1952, an event he attended and maintained a critical stance on the International Style, a reason that brought him closer to the Smithsons, Van Eyck and other architects who maintained a critical profile of the rigid and hierarchical positions of the organization. In this space, he met and discussed many of his anarchist ideals with the group (Piza, 2003). For De Carlo, the Modern Movement carried out a transformation of the architectural language through a process of imposing new social and economic conditions (Barone & Dobry, 2004).

From the ninth CIAM (1953) on, these differences between the younger groups and the founding group of CIAM became more evident, concerning CIAM's initial theoretical foundations. Allison and Peter Smithson present at this event their Urban Re-identification proposal with the aim of proposing a reintegration of man into his environment, through social cohesion, ease of movement, increasing population density, with an emphasis on human relationships.

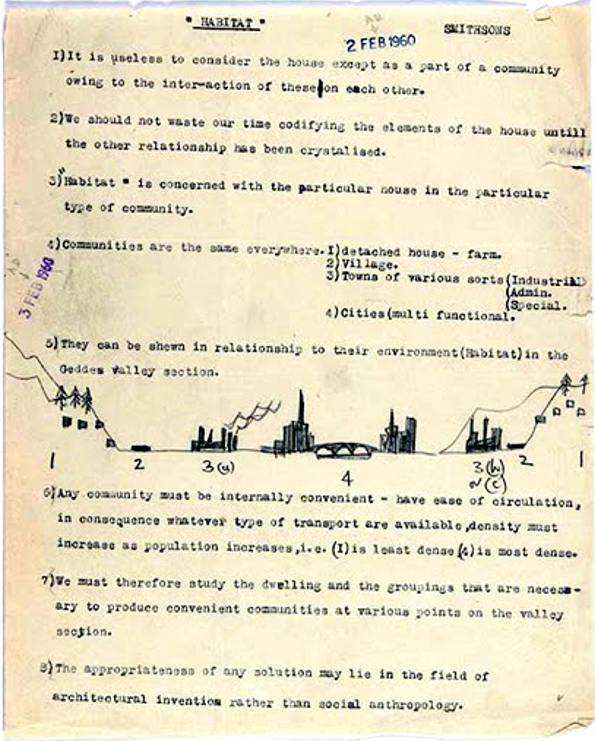

This group of young architects (TEAM X ), responsible for organizing the Tenth CIAM, published the Doorn Manifesto in 1954 , a document that emphasizes the urban space as a generator of human relations, relying on the Valley Section of Patrick Geddes, in which they defend the importance of all processes inherent to urban planning being linked to the concept of community.

The intention of the young architects was to replace the segregating vision in functions of the modern city, by a vision that made an approximation by scales (house, street, neighborhood and city) taking into account the social interrelationships established at the various levels of community (Figure 3). Of the eight points considered, four of them refer to the community as a vital point of the project:

1) It is useless to consider the house except as a part of a community owing to the inter-action of these on each other. (...) 3) ‘Habitat’ is concerned with the particular house in the particular type of community. (...) 5) They can be shown in relationship to their environment (habitat) in the Geddes valley section. (...) 7) We must therefore study the dwelling and the groupings that are necessary to produce convenient communities at various points on the valley section. Team X, 1954

This manifesto is the result of the critical stance around the initial commandments of the CIAM, materialized with the large housing complexes built in post-war Europe. The new generations sought to recover the tradition of the patio, parks and squares in the interiors of the residential areas, allowing a dynamic use by all the inhabitants of the urban space with an emphasis on human relations. At this point, some ideas proposed by Patrick Geddes of conservative surgery are taken up, on the association of new and old architectural and urban forms, emphasizing the necessary dialogical exchange between the settlers and its cultural diversity.

The tenth CIAM, considered by most of its members as the last congress, was organized in Dubrovnik - Croatia, in 1956, and was held with the intention of formulating the Charter of Habitat, an event that was preceded by a series of preparatory meetings in London, Doorn, Paris, La Sarraz and Padua, on the processes inherent to the development of the new document (Mumford, 2000). The founding members (Le Corbusier, Sert, Gropius, among others) decided to send their resignation letters before the start of the congress, causing irritation from younger members such as Alison Smithson, who proposed to hold the discussions in the garden of the event venue. In general terms, it had a condition of retrospection on the part of the attendees who did not have the presence of any of its founding members (Risselada & Heuvel, 2006).

John Turner and Peru

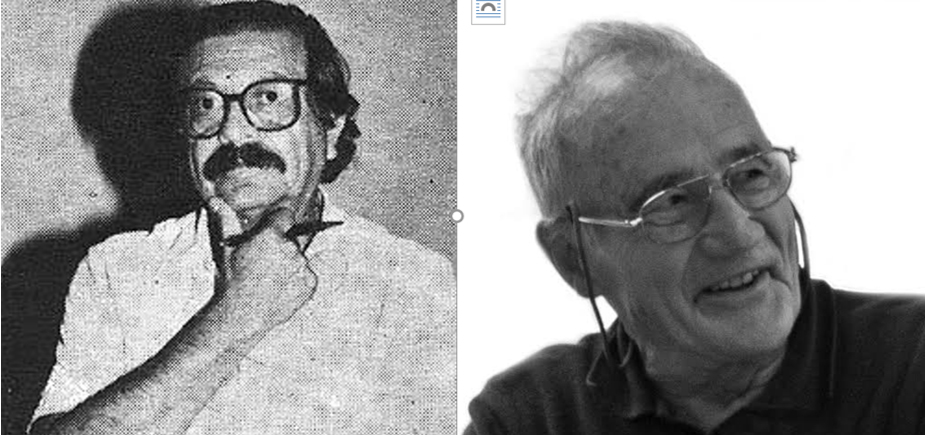

The CIAM summer schools represented a meeting point for European students and professionals in the area. In 1952, John Turner, Giancarlo de Carlo, Colin Ward and Eduardo Neira Alva exchanged ideas at this event. The Peruvian architect, Eduardo Neira Alva made a formal invitation to John Turner to go to Peru and join the technical team that assisted various newly established communities in Lima and Arequipa (Figure 4). Alva found in John Turner a good point of support for the ideas of Patrick Geddes, and the importance of community and popular action in the construction process (Dos Santos, 2014).

Once in Peru, he managed to insert himself into the Technical Assistance Office of the Popular Urbanizations of Arequipa, a technical advisory agency to the communities of the “young towns” (pueblos jóvenes), with a first project that consisted of a public school, with the use of local materials, like adobe and bamboo. John Turner was an advocate of the self-help construction, a posture he defended as an United Nations adviser in 1976.

Arqandina / The John FC Turner Archive.

Source: Figure 4: Eduardo Neira Alva (left) and John Turner (right)

Since 1940, the United States government assumed a policy of assistance and counselling to various countries in Latin America, by encouraging the production of housing through self-help and self-effort policies, promoting in the collective the importance of individual ownership in the housing issue, a soft power strategy, to control the growing communist-inspired thinking in the region. These tactics allowed the improvement of public health standards and mortality rates in many growing countries, but with the considerable loss of political autonomy and sovereignty of their territories (Dos Santos, 2014).

The policy of self-help in Latin America is promoted by different governments of the region and this is how self-help construction became the primary form of habitat production in this context.

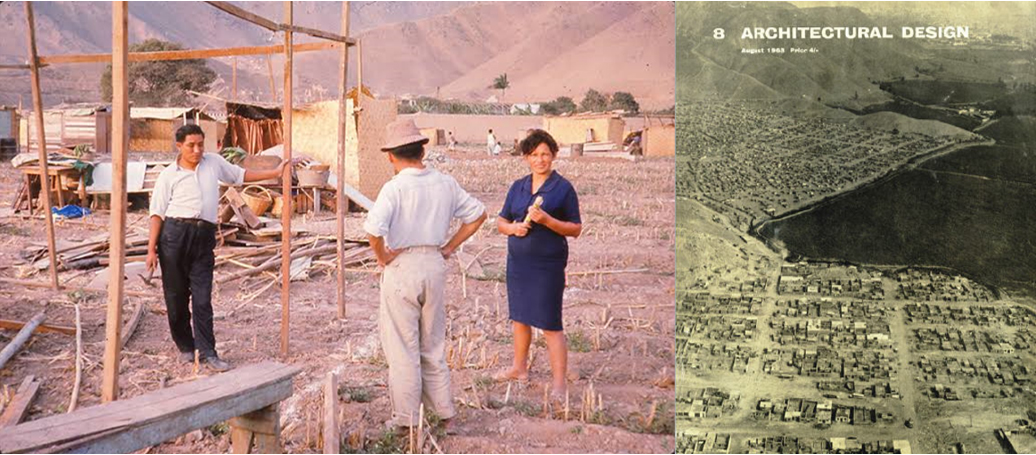

The observations of John Turner regarding his experience in Peru were disclosed in various academic publications on a global scale and in writings of his authorship (Figure 5). His compilation work arises at a time where different governments were eager to obtain answers to many questions about the abrupt development of the Latin American informal city, the participation of users and technicians in those processes, as well as the role of the State in achieving these works (Espinoza & Grappi, 2017).

At this time, the region was submerged in a precarious process of industrialization and a fragile policy of import substitution, added to a violent process of urban expansion motivated by the internal migration of people from the countryside to the city in search of better living conditions.

John Turner Archive.

Source: Figure 5: El Ermitaño, Lima - Perú (left), cover of Architectural Design Journal No. 8 (right)

During the same period, the North American urban planner Charles Abrams (1901-1970) criticized the self-help policies as a form of habitat production, considering it “a primitive and unsuitable representation of the technological transformations of the moment”, difficult to access for populations with limited economic resources. Self-help was understood by Abrams as the failure of the institutions to provide the popular sectors with more efficient technologies to supply the housing demands. In this sense, it dismisses the methods of self-help for the additional time required by population, as well as the inherited constructive problems of delegating this work to the proper residents.

John Turner's work was is in this sense more convincing and defender of the self-management capacity of the population, probably motivated by the influence of humanist and anarchist writers (Patrick Geddes, Lewis Mumford, Peter Kropotkin), identified with a more respectful vision of the popular and local culture, as well as the creative power of each individual. Not surprisingly, the contributions of John Turner are still valid in the academic field fifty years later, and at that time they represented an anchor point between the global south and the hegemonic centers of power (Harris, 2001).

John Turner highlighted the importance of the horizontal organization of these new settlements, where the community assumes the operation of the space, ending in some type of association carried out voluntarily by its own inhabitants, who at a later stage made alliances with government agencies to formalize those settlements and provide them with health conditions and resources to consolidate the neighborhood. Those informal settlements were constituted under the notion of freedom of access for anyone who wanted to live in that place, freedom that was manifested in the possibility of self-administration of the own resources to constitute a new habitable space. A democratic space that allowed the establishment of any person to the place, a space of diversity, exempt on rigorous criteria of choice of housing complexes granted by the State (Espinoza & Grappi, 2017).

Before the arrival of John Turner in Peru, other architects of global importance had visited the Andean country, such as José Lluís Sert, Paul Lester Wiener and Ernesto Rogers, who contributed to the dissemination of the CIAM’s ideals and made proposals for urban reforms in Chimbote and Lima (1948). During the period from 1948 to 1968, Peru was an experimentation territory for various pioneering proposals framed in the industrial construction methods outlined in the Modern Movement (Ortiz Agama, 2017), highlighting in 1967 the PREVI contest (Experimental Housing Project) with the participation of various architects belonging to the so-called star system, under the important auspices of Fernando Belaunde, architect and president of Peru for that date.

Final considerations

Trying to find out the origin of the inclusion of the inhabitants and the community concept to the architectural project process consisted of an intense review of a series of factors exempt from all homogeneity and involved, in the case of this work, a reconstruction of different facts and the human relations established around those facts.

The discussions that took place at CIAM in which the absolute hierarchy of the professional was questioned vis-à-vis the communities are complemented by some pioneering project experiences, in which the notion of authorship of work is disregarded and fully transferred to the users in the architectural project.

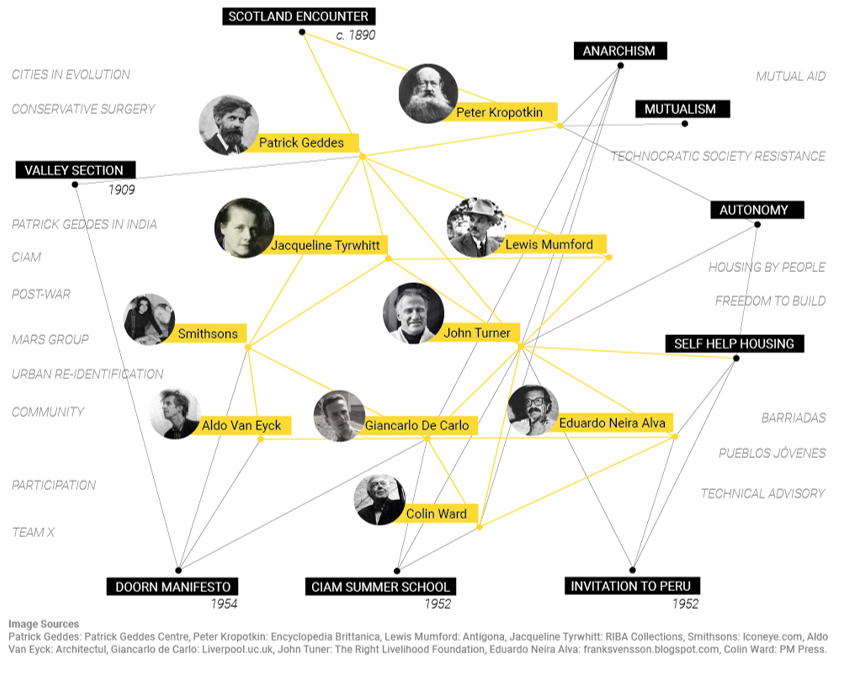

In the following diagram (Figure 6), an attempt is made to explain in a synthetic way, the relationships indicated above. The diagram shows in yellow the main characters; in black, key topics, and in both sides, main references and discussions associated to each character.

Own elaboration.

Source: Figure 6: Relationship Diagram (Sociogram) between Patrick Geddes, Team X and John Turner

The experience of working together with the communities is a work that dignifies, values, and raises awareness of architectural practice. This involves a process of recognition and clash with the reality of most of the geographic space of our cities - unequal in essence - and eager for expeditious solutions to the great contradictions that prevail in our context.