Introduction

This research explores key protest movements that have found musical expression in Aotearoa New Zealand’s1 unique political environment and social history. Popular songs play an important role in mobilising political campaigns by creating platforms for voices of protest and dissent in the discussion of significant issues that questions those in power. Noriko Manabe (2017) recently noted that since its rise in the 1960s in the USA, protest music is still ‘going strong’, although economic and technical changes in the music industry have affected what music gets recorded, distributed and emphasised through media exposure. Aotearoa went through a process of decolonisation from Britain starting in the same period (1960-1986), introducing a wide range of socio-political issues into the process of gaining a new identity as a nation (Belich, 2001).

In Aotearoa, political messages have been expressed in a variety of musical styles reflecting the region’s unique historical and cultural development, especially through the positioning of its Pacific peoples (indigenous Māori and immigrant Pacific Islanders and their descendants) in the issues and processes of political unrest. Out of the decolonisation process came the growth of Aotearoa’s culture of support for local content and musical voices. Harris et al. (2016) note that in the 1960s and 1970s, when global human rights movements were gaining traction, in Aotearoa there was a growing recognition of intense inequities and injustices in society. Māori land rights claims (ongoing since 1975), Pacific Island community home evictions (1974-1976), sporting relations with the apartheid regime in South Africa (1981-1994) and the French programme of nuclear testing in the Pacific (1974-1996) were all issues of major concern, ones that provoked marches, occupations and boycotts. Some of these movements found expression in the voices of musicians and bands participating in new developments in the nation’s popular music.

From a sociological perspective, Roy and Dowd argue that what is of particular interest in protest music are the frequent instances in which musical production is explicitly collective-where individuals and organisations with their own respective interests come together for delivery of music-which they call a “technology of the collective” (2010, p.190). Where traditionally protest music has been rooted in folk traditions, the use of reggae, rap, post-punk, heavy metal and experimental music, in a variety of languages, has added to the growth and diversity of audiences for protest songs. With changes in technology and marketing, performers and companies have chosen to, or had to, bypass the mainstream music industry, creating new spaces for music delivery. As pointed out by Guerra, “music enables groups to establish collective identities by allowing a means for them to differentiate themselves, aggregating individuals with similar cultural tastes and practices” (2020, p.15).

Music commentator Simon Grigg (2014) stated: “The story of political song in New Zealand is a mixed one. It goes from almost nothing to a flood to a trickle.” From my observation since 2010, it appears that voices of dissent and political action have been on the increase in the areas of climate change, Māori land rights and sovereignty issues. There are many recent popular recordings in Aotearoa that include messages of political discontent and voices of resistance by well-known artists. With this in mind, three key questions underpin this enquiry:

1) What are the ongoing campaigns of protest and dissent, and how are these campaigns reflected in popular song?

2) What effects have economic and political changes had in terms of which voices get heard?

3) Who are the current performers and what are their political concerns?

The Study Setting: Aotearoa

Aotearoa, an archipelago slightly larger than the UK, was discovered by Māori who sailed in canoes (waka) from Eastern Polynesia. The arrival date is debated but was approximately 800 years ago. The Māori settlers (tangata whenua, people of the land) established a tribal society and created a distinctive indigenous culture. European exploration in the Antipodes in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries led to Aotearoa’s colonisation by Britain in the nineteenth century (Salmond, 1992). In 1840, representatives of the British along with Māori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi, which declared British sovereignty over the islands and under the understanding of Māori chiefs that they would be guaranteed tino rangatiratanga (full authority) over taonga (treasures, which can be intangible). The precise nature of the agreement effected through the Treaty of Waitangi continues to be a matter of debate. In 1841 New Zealand became a colony within the British Empire. The country gained full statutory independence from Britain in 1947. The British monarch remains the head of state and the country is a member of the Commonwealth.

After independence, with close links with Pacific Island nations (Samoa, Cook Islands, Fiji, Tonga, Niue, Tokelau) reinforced by the impacts of World War II (military occupation, exploitation of resources, lack of employment opportunities and devastation of land and pollution from nuclear testing), job opportunities and population pressure on some islands led many Pacific people to migrate to Aotearoa. Since 1960, Aotearoa has pursued a social, economic and political process of decolonisation in a bicultural society (European and Māori), population growth, and a shift from being a predominantly European society to a multicultural nation. With the arrival of new cultural influences, through globalisation and new waves of migration, came the birth of Aotearoa’s local media industries.

In 1972, a petition was delivered to Parliament asking for active recognition of the Māori language, te reo Māori2, that became the starting point for a significant process of revitalisation of the language and its cultural significance. With the early 1980s came the Māori cultural renaissance, which emphasised issues such as sovereignty, tikanga (customs) and the survival of te reo Māori and stimulated awareness of identity among Māori musicians (Keane, 2012). Pacific Island and Māori artists introduced hip hop to Aotearoa to offer oppositional racial and political messages through performance. In the case of Māori performers, the use of te reo Māori has become increasingly common in song lyrics.

Aotearoa’s population has grown in size and diversity over the 60-year period that is the focus of this study. According to the 2018 census (Stats NZ, 2019), the country’s total population was 4.7 million. The majority of the population (70.2 percent) in 2018 identified their ethnicity as European (including Scots, Irish and other British ethnicities), a proportion that is shrinking (in 2013 it was 74.0 percent). The 2018 census recorded a total of 381,642 people from over 30 distinct Pacific Island groups living in Aotearoa, 85,701 more than was recorded in 2013. About two-thirds of these (243,966 people) lived in Auckland, the country’s largest city.

In 2018, 181,194 of Auckland’s residents identified as Māori (11.5% of the city’s population), up from 142,764 in 2013. The Māori population has grown more rapidly than the wider Auckland population. The Pacific Island and Māori populations in 2018 were much younger than the European population. The median age was 23.4 years for the Pacific ethnic group, 25.4 years for Māori, 31.3 years for Asian and 41.4 years for European (Stats NZ, 2019).

The 1960s saw the start of profound change in NZ’s relationship with Britain. Whereas in 1965 ‘Mother Britain’ had been responsible for purchasing over 50 percent of all NZ exports, by 1989 that proportion had dropped to 7 percent. Not only had British investment in NZ been inadequate in the decades prior to decolonisation, the fundamental economic relationship had disintegrated as well. As a result, the nation underwent major economic, political and social reforms (Belich, 2001).

With the 1960s came a change in government funding support for music. Government funding began to support cultural policies that helped foster a unique and active New Zealand popular music culture, with policymakers recognising the important role music could play in the nation’s emerging identity. Opportunities opened up for independent record companies and producers to flourish. Musicians, recording studios and radio and television stations all benefitted from the establishment of central government-controlled arts agencies. NZ On Air, introduced in 1989, helped the New Zealand recording industry, marginalised due to the small size of the local market and lack of resources and market exposure, grow in the international arena (Shuker, 2008).

The increase in bars and clubs featuring local musicians, commercial and independent record labels, music TV shows and rock radio stations also contributed. Since 1965, Aotearoa’s most prestigious music awards, recognising artists’ contributions to Aotearoa’s music industry, have been distributed by Recorded Music NZ and the Music Producers Guild of NZ/Aotearoa. The awards have been rebranded over the decades, from New Zealand Music Awards to Vodafone New Zealand Music Awards in 2004 and more recently Aotearoa Music Awards in 2020. Additionally, annually since 1965, the Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA) has awarded its prestigious Silver Scroll to recognise songwriting skills amongst other awards for sales and airplay performance by its members.

Protest Songs in Aotearoa: The 1960-2019 Sample

The concerns and emotions of protest are often expressed in song and may play an important part in the civil, political, economic, social and cultural life of societies. Protests are a type of popular response to situations that are found personally, collectively or socially unbearable. This enquiry recognises that a protest is an expression of objection/opposition, by words or by action, to particular events, policies or situations.

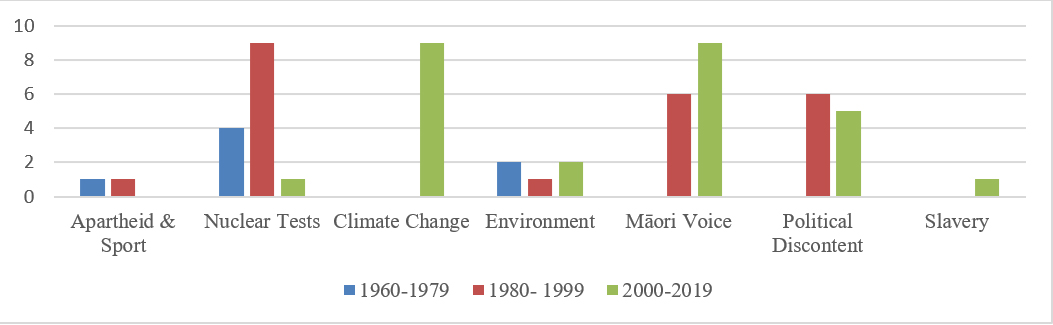

This study has involved the thematic review of musical trends of song and protest over the past 60 years in Aotearoa, creating a historical overview of the expression of voices of dissent in the production of and audiences for popular protest music recordings. Through archival searches and media accounts, 57 commercially recorded popular songs by local artists released between 1960 and 2019 were identified whose lyrics address issues of protest and political dissent. The lyrical content on which the songs focus can be roughly divided into themes representing issues of dissent in Aotearoa and its Pacific Island neighbours (Figure 1), categorised under the following headings: apartheid and sport, nuclear tests, climate change, environment, Māori voice, political discontent and slavery. The data includes singles, compilations and promotional campaign videos and is intended as an indicative overview.

The research focuses on a representative sample (Table 1) that is structured as a case study featuring 17 recordings from the larger sample of 57. Apart from providing an appropriately wide chronological distribution, this sample also ensured a selection of musical genres featuring songs that attracted media attention and public debate. An equally wide coverage of topics of dissent was ensured to gain an understanding of the direct and indirect ways in which the voices of protest make themselves heard through song. Finally, appropriate coverage of Aotearoa’s multicultural roots was taken into account by offering of Māori, Pacific Island and New Zealand European voices.

Figure 1 An overview of the selection (57) of protest song recordings (1960-2019), broken down by time period and the seven political protest themes identified in these works

The enquiry investigates patterns and thematic changes in social movement types, genres and media by focusing on identifying ongoing campaign themes of protest and dissent, economic and political changes over the 60-year period and current political concerns. The data is used to identify the campaigns, musical styles, performers and access to funding opportunities in the changing political and economic climate. It is clear that some decades produced more protest songs than others. By 2000, Aotearoa had transformed local music into a thriving creative industry that contributed to the country’s “flood” of protest music. As can be seen in Figure 1, the data seems to refute Simon Grigg’s 2014 description of the production of protest songs in NZ as a “almost nothing to flood to a trickle”, as there seems to have been no slowing in production in the most recent period.

From Folk to Pop

Of the seven well-known protest song recordings identified between 1960 and 1979, three major themes of political dissent come through: racism, nuclear tests and the environment. The first song, as listed in Table 1, is the Howard Morrison Quartet’s single “My Old Man’s an All Black”, released in 1960 to mock apartheid South Africa’s decree banning Māori players from touring South Africa with NZ’s national rugby team. The song was written by band member Gerry Merito as a parody of the international hit “My Old Man’s a Dustman” by Irish songwriter and folk singer Lonnie Donegan and his skiffle group3, recorded in the UK in 1960. The Howard Morrison Quartet, the popular all-Māori group, was founded by Sir Howard Morrison, the most successful Māori singer of the 1950s. Alongside Sir Morrison’s mainstream career, he did not hesitate to sing songs that carried socio-political messages (Mitchell 1998, p.35). The Howard Morrison Quartet also recorded a cover of Pete Seeger’s anti-nuclear anthem, “Where Have All the Flowers Gone”.

Table 1 The 17 representative recordings selected for the case study, covering the seven protest campaign themes

| Release Year | Title and Artist | Theme |

|---|---|---|

| 1960 | Howard Morrison Quartet, “My Old Man’s an All Black” | Apartheid & Sport |

| 1968 | Dave Jordan, “Hills of Coromandel” | Environment |

| 1973 | John Hanlon, “Damn the Dam” | Environment |

| 1976 | Think, “Our Children (Think About)” | Nuclear Tests |

| 1981 | Herbs, What’s Be Happen? (EP) | Apartheid & Sport, Nuclear Tests, Environment, Political Discontent, Climate Change |

| 1982 | Herbs, “French Letter” (single) | Nuclear Tests |

| 1983 | Herbs, “French Letter” (on Light of the Pacific) | Nuclear Tests |

| 1985 | Herbs, “French Letter” (Greenpeace video) | Nuclear Tests |

| 1988 | Upper Hutt Posse, “E Tū” | Māori Voice |

| 1993 | The Mutton Birds, “Anchor Me” | Nuclear Tests |

| 2005 | Various Artists, “Anchor Me” (Greenpeace video) | Nuclear Tests |

| 2011 | Tiki Taane, “Freedom to Sing” | Political Discontent |

| 2012 | AWA featuring Che Fu, “Papatūānuku” | Climate Change |

| 2012 | Maisey Rika, “Tangaroa Whakamautai” | Climate Change |

| 2016 | Unity Pacific, “Blackbirder Dread” | Slavery |

| 2018 | Ria Hall, Tiki Taane and Te Ori Paki, “Te Ahi Kai Pō” | Māori Voice |

| 2019 | Rob Ruha, “Ka Mānu” | Māori Voice |

“Hills of Coromandel” is a 1968 recording by popular folk singer Dave Jordan that gained popularity in the thriving folk club scene of the era. Jordan’s lyrics addressed the ongoing impacts of gold mining and strip mining on natural environments and local populations. Gold mining in the Coromandel Peninsula, east of Auckland, persists as an environmental issue and has been the site of recent protests reported in the press.4 In 1968, Kiwi Pacific Records released Seasons, an LP of Jordan’s songs that includes “Hills of Coromandel”, which led to him winning two Silver Scrolls. The same year, American folk legend Pete Seeger performed at the National Banjo Pickers’ Convention folk festival, held near Hamilton, two hours south of Auckland (Brown, 2015). Dave Jordan’s “Seasons”, the LP’s title song, was picked up and sung by Pete Seeger as he toured during this period, but does not appear to be included in any currently available Pete Seeger recordings (New Zealand Folksong, n.d.).

John Hanlon’s 1973 “Damn the Dam” is an example of how, with the growth of NZ radio, media opportunities were created for promoting local content. “Damn the Dam” was originally recorded as a two-minute radio commercial for NZ Fibreglass. Hanlon was an advertising copywriter and art director at the time. The commercial was part of a campaign intended by NZ Fibreglass to lobby the government of the day to make insulation compulsory in new homes. Through the commercial the song became very popular, and Hanlon was pressured by the public into releasing it as a single. He agreed to do so as long as the profits were donated to environmental protection groups. In 1973 the song was taken up by environmentalists as a protest song against a government proposal to raise the water level of Lake Manapōuri, Fiordland (in southwest NZ), for a hydroelectric dam (New Zealand Folksong, 2008). In 1973 “Damn the Dam” was awarded Single of the Year at the RATA Awards bestowed by the New Zealand Federation of Phonographic Industry (which preceded the New Zealand Music Awards; Dix, 2005).

The progressive rock band Think’s 1976 recording “Our Children (Think About)” appeared on their sole LP, We’ll Give You A Buzz. The recording exemplifies Aotearoa’s anti-nuclear stance as expressed by young performers. The track ends with a sound recording of a nuclear explosion. The LP is an example of new recording opportunities offered to emerging artists by the government’s new policies to grow the nation’s music industry and local brand identity. The album was recorded at Auckland’s newly established Stebbing Recording Centre, Aotearoa’s only full-service music recording studio and mastering and music manufacturing business. The master tape for We’ll Give You A Buzz was stolen and became a bootleg CD in the 1980s, increasing the interest, value and collectability of the album (Moffatt, 2015).

The socio-economic and political environment of the 1980s created fertile ground for dissent, with major protest campaigns that focused on ongoing nuclear testing, rugby tours and South African racism, home evictions in the Pacific Island community and Māori land sovereignty issues. With the 1980s also came technological advancement in the marketing of music, including the CD format and music videos, along with an increase in government support of popular music recordings, videos and marketing. The introduction of the compact disc in 1980, along with the establishment of NZ On Air and Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council support, led to growth in NZ’s music industry and in the market for NZ music. Shuker and Pickering (1994, p. 264) explain that “the New Zealand record market more than doubled its sales in the 1980s, with the reduction (from 40 per cent to 20 per cent), and then abolition, of an onerous sales tax which had been imposed on records since 1975 (…); the reduction of import duties; and, primarily, the introduction and growth of the compact disc”.

Land Disputes and Marginalisation

The arrival of Bob Marley in 1979 in Auckland for his concert with the Wailers at Western Springs Stadium was set against a background of racial unrest and conflict between Māori/Pacific Islanders and the authorities. The 1970s and 1980s brought a large influx of people from the Pacific into Auckland’s workforce as more labourers became required with the rapid growth of local industries. The Pacific Island community suffered ‘dawn raids’ on houses of people suspected to be overstayers in 1974 and 1976. This gave rise to political activism with the growth of the Polynesian Panther movement, associated with the Black Panther movement in the USA. In 1971, political activist, Rastafarian and reggae musician Tigilau (Tigi) Ness (performing as Unity Pacific) founded the first Polynesian Panther chapter in an area of Auckland where many of the new migrants lived. The chapter offered support for those feeling marginalised, giving birth to a new urban Pacific Island community movement.

During this turbulent period, alongside the ‘dawn raids’, Māori were being forcibly evicted by the government over disputed land as Aotearoa was becoming increasingly racially divided. The Māori land march (1975) and occupation of Auckland’s Bastion Point (1978; Belich, 2001, pp. 477-478) and the 1981 Springbok rugby tour sparked massive protests in Aotearoa against racism and, in the case of the latter, South African apartheid. Reggae became a musical symbol of dissent.

Bands such as Herbs, Aotearoa, and Dread Beat an’ Blood borrowed the reggae rhythms of Jamaica, but their music reflected the lives of Māori and Pacific Island people. As Staff and Ashley (2002) noted, these Māori bands of the 1980s created a distinctive Aotearoa reggae sound, having paved the way for contemporary reggae groups such as Fat Freddy’s Drop, Katchafire and Trinity Roots. As part of the incipient indigenous rights movement, Herbs’ upbeat music was often political. In 1981, Herbs released their EP What’s Be Happen? and emerged as a major reggae band with ten Top 20 hits on NZ’s popular music charts during the 1980s and early 1990s.

Takaparawhā Bastion Point

On 25 May 1978, police and army officers forcibly removed hundreds of protesters from Takaparawhā Bastion Point, a promontory overlooking Auckland’s Waitematā Harbour. It was the end of a 506-day protest by local Māori sub-tribe Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, who sought to retain their land and prevent the government’s plans to make the site available for high-end real estate development (Murray, 2018). Many members of the musical community supported and sympathised with the protestors. Participating in Bastion Point and the emerging land rights movement were important political actions for Herbs band members. During the occupation, there was even an in-house band, Papa Band of the Land, featuring Alec Hawke, brother of occupation leader Joe Hawke and the organiser of the concert, and Dilworth Karaka, later of Herbs, who both lived on site throughout (Dix, 2008). The cover shot of What’s Be Happen? was of police evicting land protesters from Takaparawhā Bastion Point. The song “One Brotherhood” refers to various protests of the time: land rights, civil rights, and apartheid and the Springbok tour (Gifford, 2019).

Elizabeth Turner places this key album in historical context: “The decade before the release of the album [Herbs’ What’s Be Happen?] in 1981 is described as a significant period in New Zealand’s modern history; a time of struggles over human rights, ethical values, and over the kind of society people wanted New Zealand to be. These are regarded as having shaped opinion and the sense of identity of many New Zealanders, and they led to significant and progressive changes in law” (2018, p. 2). What’s Be Happen? features six tracks with song lyrics that encapsulate the major issues of political discontent in Aotearoa in 1981. In the words of Turner:

The threads interwoven in these songs include those that stretch from the racist rhetoric and realities of apartheid in South Africa to the streets and rugby fields of New Zealand, to historical protests and conflicts over lost Māori land and cultural losses. There are threads of cultural identity and loss stretching between Pacific Island roots and the realities of life in urban New Zealand, interlinked with Pacific Island and Māori experiences of racism and prejudice. From its roots in Jamaica, the global thread of reggae meets in its localisation the strands of rhythm and sounds of the Pacific. Furthermore, the lyrics involve language choices that reinforce the construction and expression of Pacific unity and identity, while in the choice of specific lexical items or references to other texts, they position the utterances in terms of the dialogic threads of social and cultural history. (2012, p. 34)

In Auckland on 25 May 2018, to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the forced eviction of protestors at Takaparawhā Bastion Point, a concert was held featuring Annie Crummer, Ardijah, Che Fu, Harry Lyon, Herbs, King Kapisi, Moana Maniapoto, Papa Band of the Land, Ronald LaPread (ex-Commodores), Tama Waipara and Tigilau Ness (Dix, 2018).What can be noted here is the longevity of many of these musicians’ careers and the multigenerational family performers willing to bring issues to the public’s attention through song. Che Fu (Tigi Ness’s son) and other popular hip-hop performers such as Ladi6 and Scribe are just a few of the success stories of the 2000s of Pacific Island artists who had parents involved with the Polynesian Panther movement.

NGO Political Media Campaigns and Branding “Kiwi” Music

Songs as expressions of political positions and social movements have a long history extending back over many centuries (Redmond, 2014), but their interaction with the commercial music industry and the institutionalised social activism of contemporary non-governmental organisations (NGOs) is a phenomenon of the late twentieth century and into the twenty-first. A specific set of conditions in Aotearoa during the 1980s encouraged the interaction of popular songs with social activism and produced a number of songs that became closely associated with political action and are anthemic expressions of this period.

Since the 1980s, with greater government funding support for home-grown music came access to production, media, labels and distribution. The local market has provided an increasingly fertile testing ground for locally produced Pacific Island voices wanting to break into the international market. Local inflections of imported musical styles have created international interest-and sales-while maintaining a NZ flavour in the music. Polynesian-dominated local rap, reggae and hip-hop music are excellent examples of the hybridity of much contemporary music in their inclusion of elements of a distinct NZ identity (Shuker & Pickering, 1994).

Since 2000, the NZ Music Commission has been responsible for delivering a range of programmes that promote New Zealand musicians, international market development and a successful music industry in Aotearoa. With the deregulation of radio and television, the NZ Broadcasting Corporation was split into separate television and radio arms (1989); radio then split into commercial and non-commercial programming (2002). This resulted in an influx of new commercial radio stations as well as government funded non-commercial programming. As Shuker (2008) discusses, the NZ Broadcasting Commission was responsible for funding support for broadcasting and creative work, and the fostering of New Zealand music was considered of crucial importance. In July 1991 NZ On Air introduced a number of new funding and support initiatives, including a subsidy for local music videos. These videos became valuable assets through the 1990s that contributed to a snowball effect: television play led to record sales, which put the records on radio playlists, in turn making the video clips more popular with the television shows, leading to more sales and higher chart listings (Shuker, 2008, p. 276).

Since the 1990s, some NGOs have sought to brand specific social-activist campaigns by reusing some of these songs as videos used in televised broadcasts as advertisements and editorial content. In doing so, these NGOs are able to take advantage of the political and emotional histories that these songs have built up. For example, Greenpeace in Aotearoa has used popular songs of the 1980s to create new anthems for its environmental/political campaigns, such as anti-whaling and climate change issues in the Pacific. With their well-known lyrics and melodies, such songs become easily identified with these campaigns in Aotearoa.

Aotearoa’s long involvement with anti-nuclear protests and governmental positions reached a pinnacle of activism in 1985, after French agents bombed the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior in Auckland Harbour. In addition to the expected condemnation from Greenpeace and environmental activists, the actions in NZ waters of French government operatives and their aggressive and dangerous form provoked outraged responses from the NZ government as well as the general public. As a result, the Rainbow Warrior became a potent symbol of anti-nuclear sentiment in the Pacific.

“French Letter” and “Anchor Me”

The Herbs song “French Letter” was released as a single in 1982, and again in 1983 on their LP Light of the Pacific. “French Letter” became an Aotearoa anthem for nuclear disarmament in the Pacific. In the context of both French nuclear testing and NZ’s broader anti-nuclear stance, this song, protesting the Moruroa tests, was widely popular; but in Aotearoa, the song’s title, interpreted as a British euphemism for condom, was considered too risqué for radio airplay. It was consequently released under the alternative name “Letter to the French”. The 1985 “French Letter” video remix for Greenpeace NZ became a factor in the success of raising public awareness for their campaign to stop nuclear testing in the Pacific.

The Mutton Birds’ 1993 ballad “Anchor Me” is a classic track from their second album, Salty, which went platinum in New Zealand. The 1994 Silver Scroll went to the song’s composer, Don McGlashan. The chorus includes the lyrics Anchor me, anchor me, in the middle of your deep blue sea, your deep blue sea: innocuous enough, perhaps, in the context of a romantic ballad, but offering interpretive scope for the later development of environmental meanings.

In 2005, the communication and marketing team at Greenpeace NZ organised the You Can’t Stop a Rainbow campaign to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior. “Anchor Me” was the preferred choice of music for the campaign. Greenpeace approached McGlashan for approval. Although he had rejected previous requests for the use of “Anchor Me” over the years, as a long time Greenpeace and anti-nuclear supporter McGlashan gave permission for this purpose. On behalf of Greenpeace, popular young NZ musicians collaborated to create a new cover version of “Anchor Me” as a single and video. The recording features vocals by Goldenhorse’s Kirsten Morelle, Che Fu, Anika Moa and Nesian Mystik’s David Atai. The video was branded “100% New Zealand Music” in recognition of the NZ Music Commission’s financial support. This version of “Anchor Me” transforms a love ballad into a powerful political message, beginning with a Māori karakia (prayer) and with the musicians singing against an backdrop of oceanscape, whaling and other Pacific imagery juxtaposed with images of nuclear tests. This is a fine example of an NGO redeploying a well-known song in order to use its power and align itself with the musicians for their own political purposes.

The ballad structure and simple melodies of “Anchor Me” and “French Letter” make the songs easy to sing. They feature repetitive lyrics that are easy to remember, typical of successful protest songs over the decades. These are examples of highly visible political campaigns that were able to capitalise on the outputs of highly creative musicians in a period of government support for Aotearoa’s “homegrown” music. “Anchor Me” and “French Letter” are pieces in the larger Aotearoa musical landscape.

Māori and Pacific Youth Voices

Over the past three decades, supported by government, the ability for musicians to access funding to create indigenous music in te reo has resulted in a plethora of high-quality outputs that allow traditionally marginalised voices and world views to be expressed. Since the 1990s, the growing Māori and Polynesian youth population has brought an increase in diversity of those contributing to Aotearoa’s music industry as consumers, performers, industry professionals and entrepreneurs. Since 2000, changes in technology, new government funding for music and the development of Māori performing arts have created new types of recording opportunities for indigenous voices. As Johnson and Kraft (2018) argue, when colonialism constitutes the historical framing of indigeneity, threats to homelands have emerged as the number one concern of indigenous politics across the globe.

With ongoing government support for te reo Māori and for specialised radio, TV and media with the development of Te Māngai Pāho (Māori Broadcasting Funding Agency) came a flourishing of music sung and rapped in Māori, supporting cultural affirmation and identity. As Zemke-White and Televave (2007) note, Aotearoa’s independent Pacific-oriented music labels offer something unique to the market, maintain aesthetic control and reap their own profits5.

Upper Hutt Posse originally formed in 1985 in Upper Hutt, Wellington, as a band that merged with rap. The band’s 1988 bilingual single “E Tū” (Stand Up) became Aotearoa’s first released rap track. The lyrics, by Te Kupu, are a call to action for Māori youth to stand proud and not forsake their roots by saying who they are out loud: in other words, recognise the power of their indigenous culture. At the song’s release, the group faced backlash from all sides. It was considered too political or flippant. It used profanities and was too ‘pro-Māori’. Talkback radio callers complained about the song being anti-police, blatantly twisting Te Kupu’s lyrics, and others were clearly confused with the song’s message (RNZ, 2020).

Since the song was released, public opinion in Aotearoa has changed. “E Tū” now stands as a song celebrating Māori culture and heritage. In 2016 it was awarded the Independent Music NZ Classic Record award. As Te Kupu, aka D Word, aka Dean Hapeta, commented, “It’s great for a conscious song of resistance to be respected in this way, and although it already has a firm place in the hip hop musical history of Aotearoa, this award is somewhat unexpected and therefore a little extra pleasing” (Reekie, 2016). In 2018, thirty years after the song’s release, Upper Hutt Posse were inducted into Te Whare Taonga Puoro o Aotearoa, the NZ Music Hall of Fame, as Tohu Whakareretanga or Legacy Award recipients. In the words of band member Teremoana Rapley:

It’s great to be inducted into the Music Hall of Fame, but the purpose of that song is about people standing up for what is right. It comes from the depth of understanding what your place is in this world and knowing it so well that you can stand up and lift your head and be proud of where you come from. (RNZ, 2020)

Māori Cultural Perceptions and Government Enterprises

Since 2000, with changes in technology, government funding for music and the development of Māori performing arts has created new types of performance opportunities. Since 2012, government funding through NZ On Air and Te Māngai Pāho has increased funding targeted for the development of Māori performing arts. Alongside NZ On Air, video funder NZ On Screen and Te Māngai Pāho distribute grants specifically for Māori content. Tracks were produced for broadcast on Māori radio stations.

Table 2 Recent government support for te reo Māori and indigenous performing arts funding

| Year | Te Māngai Pāho |

|---|---|

| 2012 | $465,000 for 93 music tracks, including albums and/or compilations, EPs and singles |

| 2016 | $518,000 for 116 music tracks, 47 musicians, 19 music producers and 9 music videos |

| 2020 | $750,000 for the production and promotion of music tracks and projects in te reo Māori; with additional support for inclusion in on-demand services such as Spotify, iTunes and social media platforms |

Sources: Mitchell (2014), NZ On Air (2017) and Waatea News (2020)

As Table 2 shows, funding increased between 2012 and 2016 for te reo Māori and indigenous performing arts funding. In 2012, Te Māngai Pāho awarded $465,000 for 93 music tracks with 70 percent te reo content, including albums and/or compilations, EPs and singles (Mitchell, 2014). By 2016, additional funding was distributed for recordings, performers, and the support for te reo music videos (NZ On Air, 2017). Traditionally the tracks were produced for broadcast on iwi (tribal) radio, but more recently funding has been available to get works included in the databases for on-demand streaming services. Waatea News (2020) reported that $750,000 was allocated for the production and promotion of music tracks and projects in te reo Māori. This has resulted in far wider distribution and greater ability to expand audiences on a global level.

Table 3 Māori community perceptions of culture and the environment from 2018 New Zealand Census data

| Measure (%) | Very/quite important | Somewhat important | A little or not at all important |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health of the natural environment | 92.3 | 6.0 | 1.7 |

| Looking after the environment | 85.4 | 11.4 | 3.2 |

| Being engaged in Māori culture | 47.8 | 25.9 | 26.3 |

| Using te reo Māori in daily life | 33.7 | 20.2 | 46.1 |

| Spirituality | 50.6 | 16.5 | 32.8 |

| Religion | 27.1 | 14.0 | 58.9 |

Source: Stats NZ, 2020.

As indicated in Table 3, the 2018 NZ census figures indicate that the Māori community considers the natural environment, spirituality and indigenous culture as very important. As noted by Charles Royal (2020), in the Māori world view, the land gives birth to all things, including humankind, and provides the physical and spiritual basis for life. Papatūānuku, the land, is a powerful mother earth figure who gives many blessings to her children. Recent award-winning recordings include Māori cultural perspectives embedded in lyrics and music videos. Waiata (Māori song) lyrics are often from the Scriptures and or refer to Māori indigenous belief systems.

Recent Voices: Land Occupation, Environment Videos and Freedom to Sing

“Papatūānuku” (Mother Earth), Che Fu Toitū te whenua, whatungarongaro he tangata Land is permanent, man disappears

Climate change is an issue being addressed within Māori worldview perspectives. Several waiata featuring powerful government-funded videos have been created evoking climate change campaign messages that blend Māori voices and environmental concerns connected with land exploitation and development. Historical confiscation of land remains central to the site of Aotearoa’s largest current political conflict at Ihumātao (2015-2021), a large portion of land near what is today Auckland Airport. This was New Zealand’s largest protest and land occupation since 1978 at Takaparawhā Bastion Point.

In 2012, AWA featuring Che Fu created a black-and-white video recording of their song “Papatūānuku”, having received NZ On Air video funding. “Papatūānuku” is performed with English lyrics and is presented in a Motown-styled soul genre. The lyrics speak of needing behavioural change to maintain a healthy planet to avoid the disappointment of Papatūānuku. This recording, when contrasted with Maisey Rika’s “Tangaroa Whakamautai” (2012) and its video, illustrates the diversity of musical styles and visual design in the delivery of similar political messages.

Rika’s award-winning video for “Tangaroa Whakamautai”, also funded by NZ On Air, received additional promotion by NZ On Screen. Rika performs a soulful karakia, in te reo Māori, to invoke Tangaroa, commander of the tides, to provide evidence of life forces. The instrumentation includes a string quartet and traditional taonga pūoro (Māori musical instruments)6. The video places Rika in the forest of Rotorua and the smouldering volcanic landscape of Whakaari/White Island interspersed with ocean shots.

Indigenous Land Rights: Ihumātao and Bastion Point

The 2018 award-winning Māori waiata “Te Ahi Kai Pō” (The Fire Burning Away the Darkness) was written and performed by Ria Hall, Tiki Taane and Te Ori Paki. The lyrics refer to finding peace in the aftermath of war and draws on Ria’s own Māori family history at Pukehinahina (Gate Pā) in response to ongoing issues of Māori land rights. In April 1864, during the New Zealand Wars, the British had suffered catastrophic defeat against Māori at Pukehinahina. They retaliated at Te Ranga in June, with over 100 Māori dying in that battle (Ministry for Culture and Heritage, 2019). Some were buried where they fell, leaving scars on Papatūānuku that today link the past to the present.7

“Te Ahi Kai Pō” was dedicated to the protracted protest concerning sovereignty issues at Ihumātao. Māori are believed to have settled Ihumātao as early as the fourteenth century. From 2015, ownership was contested after 480 houses started to be built by developers. By 2019, the site had attracted thousands of protesters, becoming a space for a variety of traditional and contemporary music. As the occupation created a ‘village’, traditional Māori protocol was observed, requiring performances for welcoming guests, blessing sites and offerings in song. Besides traditional performances, popular musicians offered on-site performances and support, including Stan Walker, Rob Ruha, Moana Jackson and Maisey Rika. Concerts, music videos and albums were produced to raise funds and awareness for the cause.

In 2019, Maisey Rika organised musicians from around Aotearoa to produce a recording and concert inspired by Ihumātao and other issues that have affected ‘first nations’ worldwide. The Frontline concert fundraiser for Ihumātao was held at The Studio in Auckland and launched the digital release of the album Toitū Te Whenua (let the permanence of land remain intact). The performance featured a line-up of well-known Māori artists including Unity Pacific (Tigilau Ness). Profits were donated towards sustaining the ongoing protection of Ihumātao. In the words of Maisey Rika:

There are so many of us feeling inspired to write and sing about the importance of the preservation of land, so we decided to take some action together by creating an album and putting on a concert. It is to honour our Ihumātao whānau [family], actually all our First Nation people taking a stand around the world for land and people. (Black, 2019)

Another song inspired by Ihumātao is Rob Ruha’s “Ka Manu” (The Birdling), which was partially recorded on site at the occupation in 2019 and was completed at Auckland’s Parachute Studio with a crew of well-known young Māori performers. Rob Ruha relates the growing conflicts at Ihumātao to those at Mauna Kea (Hawai‘i) and Standing Rock (South Dakota) against the continued marginalisation of indigenous peoples and perpetual injustices both historic and current, which are immense burdens to carry (Waipara, 2015). Ruha’s waiata speaks of unity and peaceful resistance with lyrics based in the Scriptures. The essence of the lyrics is from Matthew 14:24-31 and the tune is from a Ringatū8 hymn.

In December 2020, five years after the occupation began, a deal on the future of the land at Ihumātao was announced by the NZ government. The breakthrough deal to buy the disputed land brought an end to years of protest involving hikoi (marches), petitions, court action, a trip to the United Nations, a lengthy land occupation and fundraising campaigns (Trevett, 2020).

Injustice and Political Dissent

In 2016, Unity Pacific recorded its album Blackbirder Dread, written and performed by Tigilau ‘Tigi’ Ness. The title track, “Blackbirder Dread”, casts light on the rarely mentioned history of ‘blackbirding’-or slave-taking-in the Pacific in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Historically, this was a common practice whereby Pacific Islanders were kidnapped and used as forced labour, in particular on sugar and cotton plantations in Australia. Practices with parallels to blackbirding continue today. “Blackbirder Dread” draws attention to the recent Pacific Island slavery trial in the New Zealand Courts, which ended in prosecution (New Zealand Herald, 2020). Ness’s recording highlights that despite decades of protest and resistance people of the Pacific remain vulnerable.

In April 2011, the well-known musician and political activist Tiki Taane was visited by police during his performance at Tauranga’s R18 Illuminati Superclub. Taane, after performing the 1988 anti-police protest song “Fuck Tha Police” by American rappers N.W.A.9, was handcuffed, arrested and kept in jail over night with a charge of inciting violence for performing N.W.A.’s song. Taane’s choice of performing rap was considered threatening to the establishment and demonstrates, as noted by Feixa and García, controversial rap performances are not restricted to the black urban youth of the genre’s US roots (2020, pp. 90-91). Taane’s charge was later dropped, with the police citing a misunderstanding. Taane remained resolutely unapologetic as he was incensed at being arrested, for the first time in his life, over his choice of repertoire.

“Freedom to Sing”, recorded a month later at the same venue, was Taane’s defiant musical response to the ordeal. Armed only with an acoustic guitar-the protest singer’s traditional instrument of choice-he asserted his refusal to be silenced while firing a broadside at police, the media and politicians. From “Freedom to Sing”:

You can charge me with whatever you want But you can’t take my freedom to sing You can lock me up and throw away the key But you can’t what’s inside of me Ooh freedom, freedom to sing (Tiki Taane, 2011)

As noted by Guerra, “as a musical universe, the protest song has encompassed (and encompasses) a constellation of stylistic, aesthetic, contextual and ideological ingredients associated with folk music” (2020, p.15). As in the popular folk music style of protest songs such as “Where Have All the Flowers Gone”, “Freedom to Sing” features a tune that is easy to sing, thus encouraging the audience to sing along. A recording of the concert was offered online to download for free. In November the same year, Taane was honoured with three awards, including Best Male Solo Artist, at the 2011 Vodafone NZ Music Awards, where he performed “Freedom to Sing”. The performance included additional musicians as well as members of the NZ police force joining him on stage, dancing and singing, in support of Taane’s personal experience of injustice and his powerful voice of political dissent.

Concluding remarks

This research has demonstrated how the voices of popular song, from the 1960s onward, have reflected popular opinion on social and political events and issues that have been fiercely contested and debated in Aotearoa. The songs themselves have contributed to Aotearoa’s sense of its own identity and strength as a multicultural society and have helped to shape the nation’s unique history. The results show how protest songs continue to play an important role in mobilising local and international political campaigns and in supporting the messages of marches, occupations and boycotts. Some political campaigns, such as those against apartheid and nuclear testing, have finished, and others are ongoing, such as those on climate change, Māori land rights, modern slavery and indigenous sovereignty issues.

The early recordings of Howard Morrison in the 1960s and later Herbs in the 1980s drew the public’s attention to the political nature of international sporting events associated with South Africa’s apartheid policies. In the 1980s nuclear testing in the Pacific became a major political topic expressed through popular hits by The Mutton Birds, Herbs and others. Greenpeace’s successful 1995 media campaign, featuring “French Letter” and “Anchor Me”, resulted in the banning of further testing in the Pacific. Without the government’s support for the production of creative content (popular music recordings, marketing and digital technology), producing such a media campaign would not have been possible.

As in other parts of the world, the rise of new digital technologies has profoundly reshaped the production, dissemination and consumption of popular music. These advancements in technology have created affordable and accessible platforms through which musicians can create and distribute music. As argued by LeVine (2015, pp. 1280-1281), music has been far more democratised by social media than has any other art form, and consequently small producers have the ability to produce and circulate high-quality recordings to a global audience at low or no cost, thus evading the constraints of both capital and government.

The availability of funding for music videos, online marketing and te reo Māori content has added to the quality and distribution of the creative works produced by Aotearoa’s musicians. Maisey Rika’s “Tangaroa Whakamautai” is a highly technical video that was able to be produced with the help of New Zealand On Screen and te reo Māori language funding for creative works. The awards Aotearoa bestows on musicians have played an important role in elevating the prestige of protest songs over the past decade-with “Ka Manu”, “Te Ahi Kai Pō” and “E Tū” as exemplars from the case study sample. Performers have also woven their political messages into international campaigns over mutual global concerns, for example Rob Ruha relating Ihumātao to North American indigenous land rights, Tigilau Ness’s concerns over ongoing slavery in the Pacific and Tiki Taane’s stance on free speech and his freedom to sing.