Introduction

In 2013, a young Catalan immigrant in Norway wrote a controversial article entitled “La Generación T nos ha arruinado” (“Generation T has ruined us”), which has recently been published as a book (Sala i Cullell, 2020). In the article, Josep Sala i Cullell, then a young man of 35 years of age, denounced the political, economic, media and cultural appropriation of what he named “Generación Tapón” (Generation Bung), referring to people born between 1943 and 1963, who studied under the Catholicism of the Franco regime and have occupied positions of responsibility in the country from the Transition to democracy to the present day. According to Sala i Cullell, this generation is responsible for monopolising the resources of the state and making themselves rich at the cost of exploiting and indebting future generations1. This generation also created the great cultural myths of the Transition, among which can be found the singer songwriters and, in my opinion, the “Movida madrileña”2 (Fouce, 2006).

With his publications, Sala i Cullell, a member of the Generation X, expressed his frustration for a feeling of injustice due to unfulfilled expectations. At the age of 35, far from finding himself in the expected situation, reproducing the model of his parents from whom he had learned what his life should be like at that age (with his own house in his native land and a job with responsibilities) Josep Sala i Cullell was a migrant who, to make a living, had had to leave his community and, to make his presence felt, had to use the Internet. However, with his publications, and thanks to the digital media, Josep Sala i Cullell soon managed to put himself in the public eye, particularly after the release of his book, which gained him the attention of important national media. In academic terms, which is what interests us here, the life of Sala i Cullell, seems to embody well certain aspects of this late modernity (Giddens, 1991; Bauman, 2000), this new phase of the process of globalisation (Appadurai, 2001) in which inequality increases and new digital technologies remediate the public arena and its social relationships, accentuating problems of time and space. Crisis, precarity, exclusion, inequality, mediations, technological disruption, and processes of deterritorialisation and detemporalisation makeup, therefore, a context in which conflicts proliferate among different social agents.

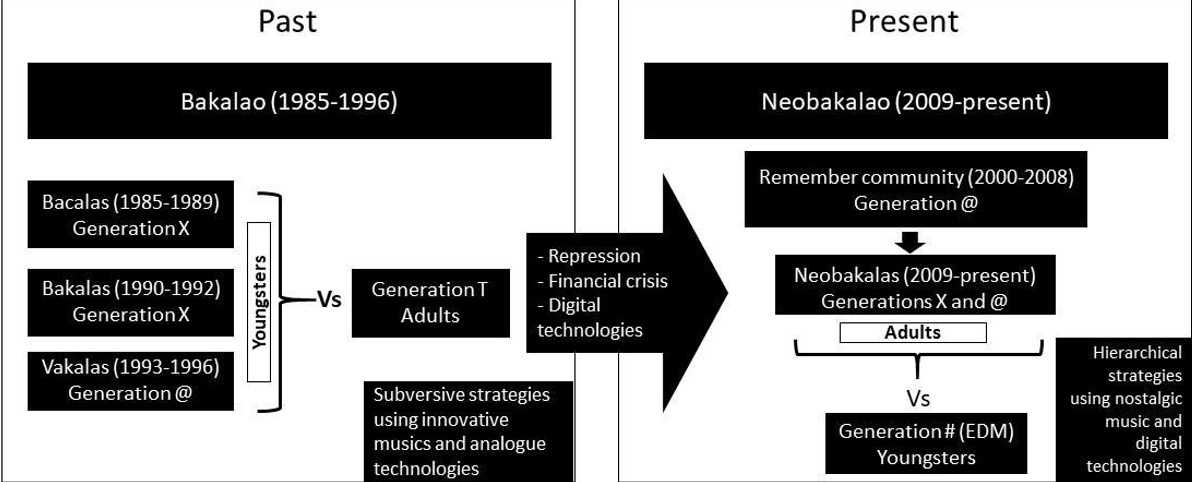

In the field of music, these processes of change and their resulting conflicts are also present and, likewise, appear in intergenerational terms. In this regard, the neobakala scene3, the main topic of this article, is particularly interesting for three reasons. First of all, because it is a scene consisting of adults belonging to different generations 一X and @ (Feixa, 2000; 2006) 一 which fight among themselves via digital media for the construction of a nostalgic narrative. Secondly, because they use this nostalgic narrative to position themselves against another musical scene led by young people from generation #, the electronica dance music (EDM). And, thirdly, because in the genealogy of this scene, that is, in the bacala, bakala and vakala youth cultures (Feixa 1998), which are today the object of the neobakalas’ nostalgia, an intergenerational conflict also emerges: that which arose via analogue media among young people who created these cultures and the generation T. This conflict from the past, the reconstruction of which I will address in this article, proves particularly interesting as it enables us to fix the memory of the bacalas, bakalas and vakalas, and to observe how the neobakalas, when building their nostalgic narrative, forget many aspects of their past (among them, their uprising against the adults of generation T). This forgetfulness will help us to qualify certain assumptions of the concepts of generation and nostalgia as both of them almost automatically assume the presence of a past, which has either been forgotten or invented (Hobsbawm and Ranger, 1983). Lastly, the analysis of the neobakala scene and its comparison with the bacala, bakala and vakala cultures enables us to see two “technological dramas” (Pfaffenberger, 1992) resolved in different ways (Image 1).

Defining generations X, @ and #

The neobakalas constitute a virtual scene (Bennet and Peterson 2004), the everyday life of which is concentrated on Facebook, which rejects the EDM scene due to both its music and the technology employed in its production. The neobakalas’ rejection of EDM and its digital technology can be understood in musical terms but can also be interpreted in generational terms due to the fact that, in general, the neobakalas are adults while the followers of EDM are young people. In this regard, the generations conceptualized by Feixa (2000, 2006, 2014) and Feixa, Fernández-Planells & Figueras-Maz (2016), generations X and @, who nourish the neobakala scene, and generation #, which gave rise to EDM, will be of great use in: articulating the opposition between neobakalao and EDM; understanding the neobakala scene itself, in whose origins the remember community can be found; and, lastly, defining both the context in which the bacalas, bakalas and vakalas lived and that in which the neobakalas live.

For Feixa, the members of generation X (Feixa, 2006), to which a considerable number of the neobakalas belong, were young people born after 1965 who reached their prime around 1990. In Spain, this was the generation of the skinheads, squatters, bacalas, bakalas and, in some sense, also of the vakalas. These people lived their youth in an analogue time among cassettes and vinyl records (Feixa, 2003), in other words, in a context marked by the persistence of the nation-state and the industrial economies, by a linear conception of time (childhood→youth→adulthood→old age) and by a relatively clear definition of roles (young people-students, adults-workers, old people-retirees). In any case, these societies, in spite of living in a linear time, experienced and led a nascent cultural disorder, promoted by media such as television (Martín-Barbero & Rey, 1999).

On the other hand, according to Feixa (2000), are the members of generation @, people who, as shall be seen, also feed the neobakala scene. The members of generation @ were born around 1975 and reached their prime around the year 2000 and spent their youth among websites, blogs and peer to peer downloads. In theory, due to their date of birth, these young people lived in a digital age (Feixa, 2003) in which the first virtual communities, such as the remember community were created4. They grew up, then, in post-modern, post-industrial societies, in which processes of globalisation, of cultural disorder and of the financialization of economies, which had already begun, accelerated, giving rise to the crisis of the nation-state. With globalisation, financialization and new technologies, a time of amalgamation and juxtapositions was reached, in which the sequence of child→youth→adult→pensioner was broken due to the fact that, with the new mass media and new technologies, “the structures of authority collapsed, and (…) ages were transformed into changing symbolic reference points” (Feixa, 2003, pp 23). It was a time when “social limbos” (Feixa, 2003) began to appear.

Finally, there are the members of generation # (Feixa, 2014; Feixa, Fernández-Planells & Figueras-Maz, 2016), who lived their youth in a hyper-digital age, fundamentally characterized by the intensification of the characteristics of digital time and by the expansion of new technologies and digital media: mobile telephones, streaming and the social networks. This generation is characterized by living in a viral, rather than virtual age, by approaching the “trans” rather than the “multi”, by constant mobility and the disassociation of fixed social, cultural and professional identities. Generation # lived its youth in the financial crisis of 2008 and is the generation in which new musical scenes appeared, led by young people, such as EDM. Furthermore, this new hyper-digital context is also the framework in which the neobakalas (adults who, in their time, were bacalas, bakalas or vakalas, and therefore members of generations X and @) live.

The neobakala scene, in this regard, will enable us to see how these three generations, which represent (or claim to represent) different times, interact (Feixa, 2003). The concept of generation will also prove useful as it will allow us to shed light on the process of identity construction of these subjects, whilst problematizing it, by which I refer both to the process and to the concept. This concept of generation can, in short, be understood as a set of people who have a series of experiences within a specific context and in a specific moment of their lives, approximately between the ages of 17 and 25 (Mannheim, 1928), which are later translated into memories, giving rise to a generational identity which coexists with other identities (Abrams, 1982; Schuman & Scott, 1989; Feixa & Leccardi, 2011). Thus, the concept of generation, and that of nostalgia (as we shall see next), produces an association of context-experience-memory-generation-identity which implies the presence of a past, which, as mentioned above, I will proceed to question in the case of the neobakalas.

Nostalgia and memory

There have been different approaches to nostalgia over the years. Former approaches criticised and sometimes even despised it due to its conservative component (Jameson, 1985; Lowenthal, 1989). However, in recent years, cultural nostalgic reconstructions have been reconsidered by several scholars (Boym, 2009; Pérez, 2016; Smith and Campbell, 2017) who have argued that nostalgia cannot be essentialised as conservative, as it is used in different ways by different actors. Within the field of music, several authors (Bennet, 2013; Bennet and Rogers, 2016) have claimed that memory and nostalgia play a key role in the construction of music scenes, biographies and identities. Within electronic dance music, similar arguments have been raised to claim the relevance of nostalgia in the ordinary lives of the subjects (Hoeven, 2014). These reconsiderations of nostalgia are useful to get around the former interpretations of nostalgia. However, they are also quite problematic as they tend to equate nostalgia with memory, frequently resorting to the theoretical framework of nostalgia and leaving aside the theoretical framework of memory (and history)5:

Nostalgia, just like memory, (…) assists in reinterpreting and fixing the past and facilitates the recreation of identity. In some way, it offers legitimacy to the facts and experiences of the past. In nostalgia, certain experiences appear which have been incorporated as a vital part of existence and which constitute places and objects of memory. (Pérez, 2016, pp. 405)

For Pérez, nostalgia and memory work in the same way. Both make it possible to “reinterpret”, “legitimise” and “fix” the past. However, the case of the neobakalas will show that memory and nostalgia do not work in the same way. Indeed, we shall see how they can work inversely because, in this case, nostalgia legitimates a strategy of domination in the present and, far from “fixing the past”, it radically modifies it6. Through the neobakala scene and the reconstruction of the bacala, bakala and vakala cultures, we shall see that memory and nostalgia are two different things. They are both ways of relating to the present and the past, but they do so in different ways (Tomé, 2016; Leste, 2018). As for the present, memory tends to confront it while nostalgia avoids it. If we refer to the past, both memory and nostalgia contain aspects thereof. However, nostalgia, unlike memory, rids itself of the social relationships and historical processes which shape it. In this regard, memory normally includes positive and negative aspects, whereas nostalgia tends to focus only on the positive. Lastly, memory and nostalgia make the past and present interact although they do so in different ways. On the one hand, memory connects the past and present by embedding the former into the latter, while nostalgia acts in the opposite way. Thus, nostalgia embellishes the past to such an extent due to the difficulties imposed by the present context that it ends up inventing a past, producing a myth.

Technological dramas

In the field of music, the relationship between technology and authenticity have been widely discussed (Frith, 1988; Thornton, 1995). However, the process of social change that technological innovations produces within music scenes is not that explored7. A good way of conceptualising this process is by way of what Pfaffenberger (1992) calls “technological drama”, a process by which an agent launches a technological innovation onto the market, alters the context and causes the appearance of multiple discourses, which are often of a mythical and ritual nature8 (like nostalgia), which either compete among themselves in order to obtain a dominant position in this new context or seek to minimise the damage caused by the change9. This process, which is capable of touching the roots of a culture10, consists, in turn, of three processes which are not necessarily successive: technological regulation, adjustment and reconstitution. In this regard, the process of technological regulation is that by which “a design constituency”11 creates, appropriates or modifies the process of technological production with the aim of altering the relationships of power, prestige or wealth of a society (Pfaffenberger 1992, pp. 285). This process of regulation can be established by way of multiple strategies12 and is normally accompanied by the appearance of mythical narratives which assume or justify the regulation. The process of technological adjustment is that by which the subjects who are negatively affected by the technological change attempt to compensate for the loss ─ in terms of status, prestige or self-esteem ─ resignifying the technology by way of different strategies, such as countersignification or counterappropiation13. The process of technological reconstitution is defined as that by which either those prejudiced by the technological change reformulate/subvert the process of technological production (anti-signification) or those who benefited are capable of reintegrating any reformulation in the system.

Throughout the article, we will be able to observe the appearance of two technological dramas. In one of them, the main characters are the bacalas, bakalas and vakalas, who used the emergence of certain analogue technologies (vinyl, cassettes, pases, ecstasy) in order to produce a series of practices and, thereby, subvert parental control. The other is led by the neobakalas, who, in a new context of the expansion of digital technology, remediate (Bolter and Grusin, 1999) the analogue technology and produce a virtual scene based on a nostalgic narrative (which functions as a myth) and a series of digital practices which are no longer destined to subverting but rather to creating a hierarchy in relation to EDM. In this regard, a process of adjustment cannot be observed in the neobakalas’ relationship with digital technology, but rather a process of reintegration.

In short, throughout this text, we shall observe how a series of adults, the neobakalas, originating from generations X and @, relate with young people (members of generation #) by way of a musical, technological and temporal discourse of a nostalgic nature which I shall question here. In order to question this nostalgic discourse, this article will reconstruct, by way of memory, the past of the bacala, bakala and vakala cultures (dealt with in section 5) in such a way as to reveal the omissions and transformations which both the remember community and, later, the neobakala scene (presented in sections 6 and 7) have generated. The reconstruction of the past and its comparison with the present will also enable us to illustrate the two technological dramas mentioned above. From the methodological point of view, section 5 is based on 28 in-depth interviews carried out14 with neobakalas who, in their time, had been bacalas, bakalas or vakalas. Using these interviews as a foundation, I began a process of joining up recollections to the point of constructing memory (Díaz Viana, 2005). In section 6, I followed a similar process with the remember community, but in this case I obtained the narratives by carrying out digital archaeology on websites and chat rooms which were used at the beginning of the Millennium and are still accessible on the Internet15. Lastly, section 7 is based on a netnography (Del Fresno, 2004) performed on the most active groups of the neobakala scene.

Bacalas, bakalas and vakalas, three analogue youth cultures

“I had quite a rebellious adolescence. [Bakalao] was my way of rebelling” (César)

“Bakalao” in Madrid was made up of three different youth cultures. Below, I shall summarise each one, but beforehand, it is necessary to clarify that all three of them had to fight against a context in which “youth”, as a subaltern group, tended to be denied as a social subject by some members of the generation T. In order to illustrate this, it is sufficient to take a glance at the Informe Juventud de 1985 (Youth Report of 1985), drawn up by Zárraga, a prominent sociologist since the eighties, in which teenagers were described as people without the “capacity” or “competency” to be “social agents” (Zárraga, 1986, pp. 18). Understanding this is to comprehend the sense of three youth cultures which, as César recalls, rebelled against generation T. This occurred within the framework of the expansion of analogue technology16 (particularly vinyl and cassettes), the “technological regularization” of which was based on “segregation”.

Madrid Bacalas, 1985-1989(...) Several of us used to go together to buy music and each one bought x records and then we recorded them on cassettes. The best thing was recording cassettes from vinyl.” (Luis)

“In the 80s (...) I liked Depeche, The Cure (...) I used to buy the records, but I could not afford a player (…) I used to ask a mate to record them for me on cassette” (Clemente)

The bacalas from Madrid originated from the adaptation that a group of young people, frequently related with gothics, punks and new romantics, made of the bacalao from Valencia (Leste and Val, 2019). These young people, generally born between 1965 and 1970, that is, members of generation X, opened their own venues in Madrid, such as Planta Baja and Specka, where they started to play bacalao from Valencia: Electronic Body Music (EBM), new beat and gothic rock. It was precisely the latter genre, by groups such as The Sisters of Mercy, whose images were shown on television, magazines and album covers17, which most influenced the bacalas from both Madrid and Valencia in aesthetic terms. They commonly wore black leather trousers, boots and black belts with studs, waistcoats, black leather jackets, hats and T-shirts of their favourite groups.

On the other hand, the members of this youth culture from Madrid interacted with the technology and media within their reach, such as television, vinyl and cassettes. They were, therefore, children of an analogue time. This does not mean, though, that they were passive subjects of their time, as they also used these technologies and media for their own ends. They created a culture in which recording cassettes from vinyl and exchanging them was fundamental. In the second half of the 1980s, a time of economic growth but also of job insecurity18, these young people invested the few resources they had in music, in blank tapes and vinyl which they did not hesitate to copy and share with their friends in order to make the most of their spending. This was done by Luis and Clemente, who bought vinyl records but as they did not have the money to buy a record player, they asked others to make recordings for them. In making illegal copies of records on blank cassettes, these bacalas therefore initiated a process of “technological adjustment”, developing a strategy of counterappropiation.

Madrid Bakalas, 1990-1992

The discos set up by the bacalas from Madrid, along with other new ones, such as New World, served as a starting point for a new cohort of young people who, generally born between 1970 and 1975 (generation X), and attracted by the media and commercial progress of bacalao19, created a new youth culture, Madrid Bakalao. Musically, these young people continued to be linked to Valencia with EBM and new beat, at least until the end of 1991, when the discos of Madrid began to turn towards hardcore and early trance. As far as the aesthetics of the bakalas is concerned, it was fundamentally characterized by the use of clothing brands such as Nike Air Max trainers, Harley-Davidson boots, Levi’s and Chevignon jeans, Diesel and El Charro shirts, Ray-Ban Balorama glasses, Pedro Gómez down jackets and Levi’s denim jackets. This aesthetic difference with regard to the bacalas must be understood in the new context of production, characterized by the economic and media growth20 of those years.

Like the bacalas, these young people continued to use cassettes and (to a lesser extent) vinyl in order to produce their culture21. Consequently, blank tapes became consolidated as a counterappropiation strategy and as a means of cultural production among young people, who used them, above all, for recording and distributing contents at an affordable price. However, in the case of the bakalas, these contents were no longer so closely related with specific bands, but rather with sessions by DJs.

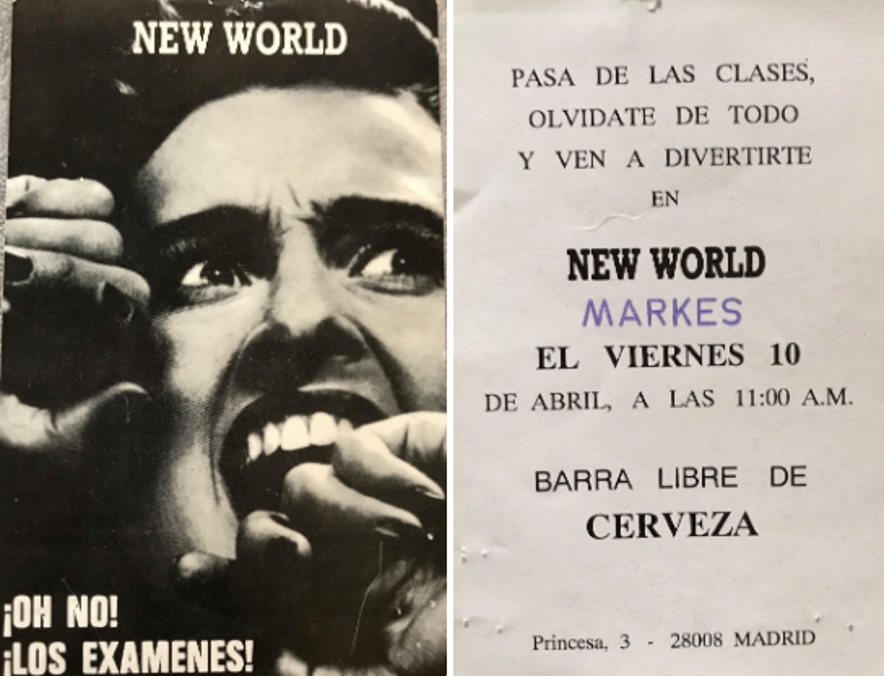

To these media were added others produced by the bakalas, the pases, that is to say, the printed publicity of the discos. The bakalas, like the bacalas and vakalas, did not create magazines or fanzines as had been done in the Movida madrileña (Fouce, 2006), although they did develop their own media in these pases, which, on occasions, mocked the institutions ruled by the generation T, such as the school (Image 2):

Madrid Vakalas, 1993-1996

“(...) We became good friends and he started to give me cassettes and that was how I started to get hooked on this culture, we were 13 or 14 years old, you know? and then (…) I had a mate around that time who was from the neighbourhood and he came with me as well, and he had an older brother (…) who brought us cassettes and pases”. (Sergio)

The cassettes and pases of the sessions of bakalao music circulated around different neighbourhoods of Madrid, attracting new cohorts of youths, who gave rise to the vakala culture. The vakalas were young people who were generally born between 1975 and 1980, members, in theory, of generation @, although they created their culture in what was still an analogue context.

From the point of view of aesthetics, the vakalas took after the bakalas in terms of some of their brands (Nike Air Max, Levi´s jeans and Pedro Gómez down jackets) and added others, such as Enduro mountain boots, large metallic buckles by Triumph, Bones shirts, Fred Perry polo shirts and bomber jackets. The clothing was tight, in an attempt to highlight ostentation and power, to the point of hyper-masculinity (García, 2010). Their music became more aggressive (hard trance and gabber), as did the pases for their vakala discos, which progressively substituted those of the bakalas. Thus, Over Drive, The Omen and Consulado-Cyberian came into existence. They did all of this in a context of economic crisis22 which led some of them to begin stealing the expensive brand-name clothes that they wore (another strategy of counter-appropriation).

Furthermore, vakala culture cannot be understood without the transformation in the media exposure of bakalao, which converted this phenomenon into a moral panic (Gamella & Álvarez Roldán, 1999), serving as a promotional campaign in attracting a series of young people drawn in by an extreme representation of bakalao, and without the economic crisis which began at the end of 1992.

Everyday life and practices of bacalas, bakalas and vakalas

“(...) I began to go out because of my friends from the neighbourhood (…) we also spent our summers together in a town in Guadalajara (…) we started in this thing together. (…) Day to day, it was cool to hang around outside the school (…) getting high on spliffs (…) [and] talking about the party you had been to and talking about the party you were going to go to the next weekend.” (César)

“When I was at primary school, my life was in Fuenlabrada. But when I went to secondary school, I started hanging around the square and began connecting with people. (…) We used to meet early in the square, having coffee while the people started to arrive (…) some for spliffs, others for pills, others for speed, others for coke (…) and you did business early in the afternoon (…) then, at eight or nine you could go out.” (Daniel)

Most of the bacalas, bakalas and vakalas were “typical” young people from Madrid with “a town”. In other words, their parents had formed part of the rural exodus of the sixties and seventies, leading to the creation of many neighbourhoods of Madrid (Observatorio Metropolitano, 2007). In this way, Fuenlabrada, Moratalaz and Oporto appeared over again in the in-depth interviews, thus making the bacalas, bakalas and, above all, the vakalas youth cultures in which the working classes were predominant. For this reason, they must be understood, to a certain extent, as the way in which the sons and daughters of the rural exodus territorialized a somewhat disjointed and precarious23 urban space.

Bacalas, bakalas and vakalas also shared a practice which, broadly speaking, was common to the three cultures: “partying”. For these bakalas, going out to party meant going to certain discos such as New World and Over Drive, where they went to dance with their friends, often for days at a time. In those years, going out “to party” meant “having a good time”, which was understood in the following way:

“I remember New World (...) there was a good atmosphere (…) you were dancing and people you didn’t know at all would offer you a drink, they’d give you a piece of a pill, (…) there were good vibes. There was empathy.” (César)

“What we all loved about it was that one guy could say to another: ‘for fuck’s sake, have a piece of pill’. And they hugged and nobody thought anything of it, you weren’t going to be any softer for that and it was great because everybody was trying to make everything okay.” (Marta)

The “good vibes” when partying, therefore, were related with dancing, offering, buying drinks, having empathy, hugging or leaving to one side the strict representation of masculinity. All of this was done to the rhythm of innovative, eclectic and transgressive electronic musics, and with a series of technologies and media, some of which have already been mentioned: mixing tables, vinyl, cassettes, ecstasy, hashish alcohol and LSD. The result was an experience with great communicative potential and was highly subversive for the age, recalling the communitas described by Turner (1982). These young people, therefore, produced an anti-significative experience, opening up a process of “technological reconstitution” which touched the roots of the culture, leading to moral panic. Furthermore, in terms of music, it should be pointed out that, in these years, young people did not have such accurate knowledge of the music they were dancing to. As César, one of the people who participated in the interviews, told me: “we didn't know much about music then, (...) we were people who went to listen to music and get high”. “Partying”, and by extension the bacala, bakala and vakala cultures, were more about corporal practice and feelings than verbal discourse. These people produced subversive cultures, by way of which they violated all types of parental control, gained presence in the media, built their autonomous spaces and demanded their rights as subjects, precisely what had previously been denied to them by the generation T.

Anyway, due to the repressive strategy of adult institutions (Leste, 2018), vakalas became extinct during the second half of the 1990s, a time in which those who were bacalas, bakalas and vakalas became dispersed in adulthood (entering into a reintegrative process). Having examined these cultures, it is now necessary to consider the attempt at reconstruction which became the remember community.

The remember community

The remember community appeared at the beginning of the new Millennium and was made up of young people who had been vakalas in its central phase (1993-1996), those who had been vakalas in its fading stage (1997-1999) and others who had had no direct relation with vakalao, but were interested in it. In general, this community was made up of people born approximately between 1975 and 1980. They were, therefore, members of generation @, although many of them (who had been vakalas) had produced an analogue culture24. This community was organised around the new technology of the time, chat rooms, websites and peer to peer downloads25, technology which gave rise to digital pages such as Omartillero, which in attempting to reconstruct the past with nostalgia created a myth:

“Welcome to the 80s and 90s, I would like to welcome all those nostalgic for the years of the Golden Age of the music and its socio-cultural movement erroneously called the Ruta del Bakalao. On this website, you will find such things as music to download and sessions from mythical venues like Over Drive and Spook, and many more which played the music we now call remember, articles about their history and their flyers.”

This attempt to “recover” the past was made by gathering and remediating objects of the past (vinyl, cassettes and pases began to be digitalised). However, in order to reconstruct that past, which they now call remember, and reclaim it as a “Golden Age”, first, it was necessary to decide how it should be defined. In this regard, of all the elements gathered from the past, the music and the discos were the key criteria for definition. The members of the community applied themselves to this task.

In theory, in this new technological context, the different participants of the community could participate equally in the reconstruction of the past, which was now defined by its music, particularly when it was circulating freely on the Internet in mp3 format. However, it was not long before some members of the community began to express their reservations. Debating about the dates the remember community should encompass and which discos had formed part of the phenomenon, in other words, attempting to define it, some members of the community (Spirit of 94, Rodrigo and Paloma) got involved in an argument regarding the establishment of its limits. The dispute focused on whether Consulado-Cyberian, one of the last vakalao discos, had truly been vakalao or not, and, therefore, whether it should be included within the narrative of the remember community:

Rodrigo

CYBERIAN was the last bastion of the old parties, both for its location (the mythical Consulado) and for its music. They played trance, acid trance, some Goa...

Spirit of 94

Guys, that dive only opened when The Omen and Over and everywhere else had closed down, it can in no way be considered a legitimate joint of the time. Among other things, the music wasn’t even good…

Rodrigo

(...) The music was bad???? Whenever you want, I’ll lend you some tapes of Pepo in the Cyberian (by the way, he played exactly the same things as in Van Vas 96-97) and Mulero...

Paloma

If you only listen to the music from Cyberian on tape or downloaded session … and you weren’t there at those sessions which you speak of with such assurance, I doubt very much that you really know the type of music they played there… How old were you in 94-97 that you have so much to say about?

For Rodrigo, who had become involved in vakalao when Consulado-Cyberian was the only place left, this disco must have been considered part of “the old parties” and should be included in the remember narrative, particularly for the music which was played there, which he thought was the same as had been played in the other discos which had been open since 1996. For Paloma, who had experienced vakalao before 1996, however, the “old music” should not extend to that after 95 or 96. Music produced in 1997 could not be included in the definition of remember. Spirit of 94 was of the same opinion, as he had also been a vakala before 1996, and for him the music from Cyberian was bad and could not be included in the narrative alongside music which he considered to be legitimate. Rodrigo, however, attempted to defend his position by arguing that the music from Cyberian was played by the same DJs who had worked in the discos attended by Paloma and Spirit of 94 before 1996. He knew this because he had listened to the tapes. This is when Paloma, who had attempted to uphold his musical criteria, drew the line of definitive exclusion: Rodrigo had no right to give an opinion because he had not actually been there, because his knowledge of the issue in question came only from cassettes and Internet downloads.

What Paloma and Spirit of 94 did, in effect, was to change the criteria of definition of the past and produce a hierarchy in a context with the tendency to treat everybody equally. They did so to enforce their seniority, their “experience-memory” and their “unmediated”26 knowledge of the past in order to place themselves above Rodrigo. This criterion, which placed experience, seniority and technology as key requisites for full participation, meant that, as other bakalas and even some bacalas joined the community, they occupied places of greater recognition. In this regard, those who had fully lived the period of bacalao, bakalao and vakalao were considered to be the most prestigious because it was they who had known and experienced “everything”. In this way, the remember community ordered this digital world, claiming ranks according to age, that is to say, reclaiming a linear and analogue time, exactly that which was being dissolved in this new context. By doing so, they began to transform subversive cultures into dominant ones, and those who were vakalas continued their reintegration process: in this community, a certain strategy of counterpropiation still survived to face segregation (P2P allowed free music, just like blank tapes did) but, as they based the community on a digital technology that very few members could modify, they accepted a regulation of differential incorporation.

The neobakala scene

The remember community lasted as long as its technology did. Around 2008, mobiles, tablets, streaming and the social networks progressively eroded the importance of desktop computers, chat rooms and peer to peer downloads. These new technologies and media, particularly Facebook and YouTube27 opened up a new range of possibilities for the remember community, whose members began to open Facebook groups on the theme of remember in general and about particular discos. Thus, groups appeared such as those of Attica, New World and Over Drive, places in which the members of the remember community went on with the task of rebuilding the “past”.

A significant number of people who had been bacalas, bakalas and vakalas began to return to these groups. It is important to point out that, although the bacala, bakala and vakala cultures had been transclass, with a predominance of working-class members, those who decided to join this new scene belonged almost exclusively to the working class. In this regard, neobakalas should not only be understood as people living in a hyper-digital age marked by processes of deterritorialisation, detemporalisation and cultural disorder, but also as belonging to a social class which was deeply affected by the financial crisis of 2008, by unemployment, job insecurity and inequality (Hernández, 2014). It is in this context that the nostalgia of subjects whose material conditions of existence are occasionally so difficult as to complicate their performance of the roles assigned to adulthood, such as economic independence, was born.

The arrival of these individuals brought about a struggle for the control of these Facebook groups, leading to their duplication in such a way that if someone from generation @ had created a group dedicated to the New World disco, those joining later, that is, members of generation X, created the group New World (OFFICIAL). These “official” groups would end up relegating the others, taking advantage of the logic of the remember community: if it were they who had “experienced” bacalao/bakalao/vakalao, the “logical” thing would be that it was they who would be responsible for “remembering it”. Thus was born this new virtual neobakala scene linking generations X and @. Now, we shall move on to examine what the everyday life of the people of this scene is like.

The everyday life of neobakalas

The daily life of these neobakalas, unlike that of the bacalas, bakalas and vakalas, whose lives were spent in the neighbourhoods, takes place on Facebook. In this remediation of their social life three aspects must be taken into account. Firstly, it is Facebook that facilitates this process. Secondly, in order to be able to use this technology, the neobakalas must pass through a ritual (via which the user must register, identify him/herself and provide his/her personal details) in which two parties who are in a position of inequality participate28. And thirdly, each time that a user goes through this ritual, he/she approves this inequality by ceding, yet again, the data of his/her future activity and activating a labyrinth of codes which will surely seem incomprehensible to him/her. The “technological regularisation” of Facebook is, therefore, of “differential incorporation”29.

The digital practices of neobakalas

In any case, in their Facebook groups, the neobakalas no longer dedicate themselves to attempting to rebuild the “past”, as the remember community had done, but rather to “remember it”. In order to “remember” this past, a series of practices takes place in these groups, among which the most common is to share music, which is normally taken from YouTube, the platform to which some neobakalas upload music from the past. This everyday practice is so important for them that they regulate it by way of extremely strict rules, in such a way that it is prohibited to share music which was not played in the disco which they are remembering or, alternatively, which does not belong to the styles played in that period30. As is frequently stated in these groups, what is important is to maintain “purity”. The music, however, is not their only way to “remember”, they also employ photos and digitalized flyers which they share in these groups31. Occasionally, all of these media, now in digital format, intermingle in the form of transmedia narratives made by members of the scene. One of them, Pepe, using photos from the New World disco and music32, created an audio-visual narrative which attempted to evoke the “memory” of the group. He accompanied this audio-visual narrative with a text:

Partying

New World, Attica, Xkandalo... What memories, what music, how we danced, what good vibes there were, our partying marked an age which will remain in history and in which we were a reference point for the world. We progressively stepped back, to the point of hitting rock bottom and we are considered, musically speaking, to be a third world country. (…) Many thanks, we were the best and we still are!!!!

In response to this text and its audio-visual narrative, the members of the group began to leave their own impressions. Below is a selection of the almost 200 comments made by other neobakalas:

Rodri What memories!!!!!! The best

Like 1

Pedro Those wonderful years....

Like 1

Julián Gil Fuck, what times they were!!!

Like 1

Jimmy Van Vas, The Omen and Over were fucking amazing too.

Henar Alonso Pfff...liquid...Specka...voltereta...Rdk...so much nostalgia, I’ve got butterflies in my tummy...what a rush!!

Like 3

Angel Sanchez What amazing times!

Like 2

Martín López I’ve read the message and I got goosebumps.....what memories. And those parties in the laberinto and in the castillito Attica and those Sunday nights in friend’s.....oh my God! What a time

Like 2

Fer Montes Amazing!!! Back to the past...

Like 1

Vicente Soto Now that was enjoying music and having a good time with friends!!!!!!!!

Like 1

Agus Sanchez fuuuuck

Like 2

Elena Martinez Attica what memories!!!!!

Like 2

Paco P. for me those were the best times of nightlife in Madrid. Now it’s all gone totally belly up and the shame is that those times will never come back, they’ll just live on in the memory of those who were there

Like 2

Manuel Torres That’s right. We are the privileged ones and for everyone who didn’t get to enjoy it… They have to be told about it and only we can do it because it will never, ever, be the same again. Good vibes

Like 2

The sequence of comments presented here is extremely common in the digital practices of the neobakala scene. Apparently, it is an attempt to make memory although, in reality, this is rarely detailed: “What times!”, “The best!”, “What memories!”, “Those wonderful years!”. These narratives and expressions of nostalgia which appeal to experiences and music of the “past” tend to create an idyllic time, a myth (“[then] we were a reference point for the world”, said Pepe)33 from which a feeling of degradation appears (“[now] we are a third-world country”) which, in turn, always leads to the production of distinction and authenticity. In this way, when Paco P. states that nightlife in Madrid “has gone belly up” and that those days “will never come back”, what he is doing is facilitating a comparison with other people from which they will always come out winners in terms of prestige. The same is done by Manuel Torres when he states that: “We are the privileged ones and for everyone who didn’t get to enjoy it… They have to be told about it and only we can do it”.

EDM

When the neobakalas say that “they have to be told about it”, to whom are they referring? To whom do they want to tell this story which was never articulated? In other words, towards whom do they direct this nostalgic narrative? The answer is simple, to the young people of generation #, a social group with whom they relate via EDM, a genre of electronic music led by young people which is produced via digital means and in which the DJs do not play live but reproduce pre-recorded sessions in order to focus on entertaining the crowd. These practices are disapproved of by neobakalas, who consider them to be dishonest and lacking in effort34. For them, “true” DJs and producers should mix or produce music live and manually35 with analogue technology (vinyls), like they did in the past. In their opinion, if music is not produced in this way, it loses value:

“Come on, (...) whenever I play at a club, I use vinyl. (...) I’m old school… I see DJs using new technology and I don’t get it… they have a button for synchronizing and the mix is… perfect. I remember when I started to DJ, there were four of us and now you turn over a stone and DJs come out from all over the place…” (Jesús)

New digital technologies make jobs such as DJing more accessible. Thus, the people that dedicated themselves to this profession years before lose their distinction. The neobakala DJs, like Jesús, resist this, establishing a new hierarchy around vinyl.

For the neobakalas, EDM DJs, such as David Guetta and Steve Aoki, are not “true” DJs. As these DJs play music with mp3 and use controllers to make the mixes for them, or even use pre-recorded sessions, the neobakalas consider them to be dishonest. For the neobakalas, David Guetta is a “mug” because he uses digital technology. He is ignorant and knows nothing about vinyl. This opposition to EDM is technological but part of the underlying reason for it is the way in which the neobakalas relate with young people. “Young people” have become a target for the neobakalas, who consider them to be people “without much information”, without “education” and with no appreciation for culture:

“It seems that its aim [that of EDM] is different. They try to attract an extremely young audience, without much information on the history of electronic music” (Arturo)

“Nothing that happens now has anything to do with what happened then, not the music, not the atmosphere, nothing. It’s a shame. [Young people] have no idea about any of this and even less about connections between people and education.” (Alejandro)

“Young people today (...) can’t make a sacrifice for anything, (...) They want everything, and they want it now… music [with downloads] have lost their value.” (Jaime)36

When faced with young people and EDM, the neobakalas resort to the “past” and present themselves as a group with culture, with “history” and even with values because young people today are unable to “make a sacrifice for anything”. This appeal to the past includes the experience of communitas which they had through “partying”, but which, now, is presented as something unreachable for the others as it is in the past. Hence, nostalgia becomes an object with patina, a guarantee against newcomers (Appadurai, 1996):

“The young people of this generation can only dream of experiencing what our eyes, our ears and our hearts have felt.” (Jésica)

In the same way as the remember community, at a time in which digital technology and media tend to democratize knowledge and, as Feixa claimed, to “collapse the structures of authority”, at a time in which the economic crisis is eroding the roles of adults, making them equal to young people, the neobakalas have produced a new hierarchy. They have created a slightly imperialistic (Rosaldo, 1989) nostalgic narrative, which gathers fragments of the past, such as bacala/bakala/vakala music, technology (vinyl) and some of their practices, such as “partying”, and transforms them into a discourse which they use37 in an attempt to dominate a scene which they considered to be produced by digital means. However, paradoxically, this hierarchy is created using digital technology, which the neobakalas cannot possess nor reshape and which imposes certain rituals, reaffirming their own subaltern situation. Thus, the neobakalas do not open up a new process of “technological adjustment” and any vestige of their subversive past has been reintegrated.

Conclusions

In the same way as Sala i Cullell, the author of the text mentioned at the beginning of the article, the neobakalas attempt to resolve the problems originating from late modernity. In a context marked by crisis, precarity, exclusion, inequality, mediations, technological disruption and processes of deterritorialisation and detemporalisation, the neobakalas throw themselves into an intergenerational struggle. In order to guarantee their status in this fight, and to solve the problems of late modernity, the neobakalas resort to a nostalgia which seeks to reclaim the order and values of an analogue time, although this is done with digital technology and practices which only accentuate the (dis)order of a digital age. The neobakalas therefore may feel empowered with their nostalgic discourse but they are actually empowering Facebook. In this regard, the concepts of remediation and, above all, of technological drama have been extremely fruitful.

The case of the neobakala scene has also enabled us to explore the possibilities, limits and ambiguities which arise from the application of the concept of generation. Generations X, @, #, and generation T have enabled us to link the genesis and interaction of the neobakalas with EDM. Furthermore, the young people born between 1975 and 1980, who produced an analogue youth culture (the vakalas) and a virtual community (the remember community) have enabled us to problematize a supposedly digital generation as generation @.

On the other hand, the exercise of memory carried out in the reconstruction of the bacala, bakala and vakala cultures has enabled us to see the difficulties involved in the association between memory-generation and memory-nostalgia. In the case of nostalgia, we have, in fact, seen how it speaks to us more of the difficult living conditions of the neobakalas in the present than in their past. In this regard, it is the necessities of the present which become lodged in the past, divesting it of its social relationships and transforming it into a myth (“the Golden Age of the music”, as stated by the “remember community”). This is why, when speaking of the “mnemonic” practices of neobakalas, I employed quotation marks for the word “remember” because these people do not seem to be remembering so much their past as the distinction or hierarchy which they have built in the present.