1. Introduction: two ways of building hybrid identity in the new stage of Chinese hip-hop scene

Since its emergence during the 1970s in the African American and Puerto Rican community in New York (Flores, 1986, p. 37), hip-hop culture (with four main components which are Rap music, DJing, Break-dancing, and Graffiti), has become a global youth culture. According to Drissel, the globalization of hip-hop is described as ‘multicultural syncretism’ that results from “cross-cultural interaction synthesizing the global with the local” in a process of ‘glocalization’ (cited in Helland, 2017). The situation makes Rap music a normal way for expressions of topics about the changes, confusions, and crisis of identity among young people, in the face of global intercultural trend, by means of self-presentation, using multilingual lyrics and combination of local and global elements. Among the research about global hip-hop, Rap music and young people’s identity expressed by it in mainland China are absent; especially, little scholarly attention has been devoted to mainland Chinese rappers after the first three stages of development of Rap music, divided by the time points of 1980s, middle 1990s, and the year 2000 (Chen, 2013). The new generation appeared around the years post-2008 crisis, when the ‘reform and opening up’ program had been carried out for more than thirty years since 1978, which had shattered the barriers against other cultural influences coming from abroad (Drissel, 2009), because of the gradually materialized consumer-based economy.

According to Schwartz, Montgomery & Briones, identity is a “social construction that refers to self-meaning narratives and self-referential modes and from which narratives about otherness are also derived” (cited by Rodrigo & Medina, 2016). In the field of culture, the ‘hybrid identity’ is constructed by the intercultural model (comparing with monocultural, multicultural and transcultural model), which encourages the culture exchange or dialogue and would potentially lead to conflicts (Rodrigo & Medina, 2016). In the context of global youth culture, hybrid identity can be explained as the space for negotiating power of nationalities, ethnicities, and social classes. It is “cultural creativity, the making of something new through the combination of existing things and patterns” (Nilan & Feixa, 2006, p.1), which “break down perceptions that national identity is homogeneous” and create opportunities for expression of diasporic communities and marginalized ethnic groups (Stadler, 2011).

With the surging development of Chinese economy and deepening international commerce, immigration, intercultural communication, and hybrid identity created by the situation have become new issues which affect the lives of young Chinese people. Similar to hip-hop scenes in other countries, we can also find discussions about the multicultural influence in Chinese Rap music. This leads to the objective of this research: to explore how young people express their hybrid cultural identity by Rap music; to identify the characteristics of their forms and intentions of intercultural communication; and to understand how these features can be related with the Chinese social context and the former development of youth culture in mainland China.

In this paper, we examine two different ways of intercultural hybrid identity construction. One of the ways is ‘being nomadic’, which means the desire to go abroad among inland Chinese young people, with the case of Higher Brothers; another way is ‘being overseas’, which is the identity explored by overseas Chinese immigrants who came back to China recently, with the case of Bohan Phoenix. Qualitative discourse analysis of the lyrics and music videos is used, with the combination of methods of narrative semiotics, visual semiology, and sociolinguistics of globalization.

2. Interculturalism in Rap Music: ‘Glocalization’, communication and hybrid identity

When it first appeared among African American and Puerto Rican young people in New York city of the U.S. during the 1970s, hip-hop had multi-ethnic and integrated origins. One of its ‘true fascination’ is ‘the growing convergence and differentiation’ (Flores, 1986, p. 35), that the original participants (African Americans and Puerto Ricans) are from different cultural context and use different languages. This original characteristic of ‘hybridity’ and ‘interculturalism’ has continued in the further development of hip-hop and makes hip-hop and Rap music an important part of global youth culture. In this process, the concept of ‘hybridity’ was explained as a third space for negotiating power of nationalities, ethnicities. and social classes, which leads to the neutral characteristic of cultural exchange: “it’s not one-way, nor is it entirely positive or negative” (Stadler, 2011, p.158). Because of hybridity, the notion ‘plural words’ appeared to describe “constitution of youth subjectivity within a number of salient discourses” (Nilan & Feixa, 2006, p.2) or, according to Lash, “relationship between the conscious self and the unthought” (Ibid., p. 2), which is an issue that young people in this era of cultural globalization have to face.

At the same time, according to Rodrigo and Medina, interculturalism can be treated as one of the four models of cultural communication (the other three are monocultural, multicultural and transcultural models), which creates ‘hybrid identity’ and strategies for promoting the intercultural communication (Rodrigo & Medina, 2016). From the author’s point of view, the identity construction of the ‘plural words’ issue can be explained by the definition of ‘myself’ and ‘otherness’, their relationship and ways of classifying them. Among all, people in an intercultural model reflect a lot about how to choose the visible aspect of their identity to show others, and to facilitate dialogue. In the process, people discover the various possibilities of identity construction, choose them, and even adjust them according to the discipline of others, which is different from the ‘uniform identity’ created by monocultural model; and ‘non-classificatory identity’ created by transcultural model without ‘otherness’, emphasizing the common features of different cultures (Rodrigo & Medina, 2016).

To improve intercultural communication, the concepts of ‘objective culture’ and ‘subjective culture’ proposed by Bennett are useful. The first one points to the large, institutional aspects of culture that don’t play a significant role in daily intercultural communication, like history, economy, political structure, and classical art. What indeed plays an important part here is the ‘subjective culture’, which means ‘the psychological features that define a group of people - their everyday thinking and behaviour - rather than to the institutions they have created’ (Bennett, 1998, p.2). Understanding this kind of culture actually helps daily intercultural interaction, and ‘is more likely to lead to intercultural competence’ (Ibid.). At the same time, reducing stereotypes is one of the main issues for intercultural communication. According to Vrij, Akehurst, & Smith (2003), there are two efficient persuasive factors for reducing the intercultural stereotype, which are (1) emphasis on similarities (same school, work and leisure activities), and (2) similarities in a positive context (e.g. ‘we both work hard’ is better than ‘both of us are poor’). This research focuses on the combination of the two mentioned aspects as the theoretical framework, which means the application of interculturalism into the analysis of Rap music.

3. Hip-hop and intercultural youth culture in mainland China

3.1. First three stages of development of hip-hop in mainland China

The initial development of Rap music in mainland China can be divided into three main stages by the following time points: 1980s, middle of 1990s and the year 2000 (Chen, 2013). The years of the first stage were culturally defined by Blåsternes as ‘Post-Mao era’ after the ‘revolutionary China’ when the cultural products were a representation of the ‘voice of the state’ (Blåsternes, 2014, p.14). The core change in the cultural field was the awakening of individualism following a collectivistic era and the ‘sudden exposure to Western culture’, which led to the superficial imitation and expression of curiosity in songs. In the field of hip-hop, the popularities of visual elements of hip-hop like Breaking dance and Graffitti was one of the characteristics of that age, with the influence of movies like Breakin’ (1984), a musical film directed by Joel Silberg, inspired by a documentary film depicting a multi-racial hip-hop club in Los Angeles in the 1980s. The plot is based on the story of Kelly, a young dancer who after meeting two street dancers confronts his instructor in the academy and decides to learn breakdance. The troupe decides to participate in a dance competition, winning against traditional dancers. The troupe’s popularity skyrockets, and all three members continue dancing professionally and in the community.

The second stage of Chinese hip-hop was during the mid-1990s, when Korean and Japanese popular culture deeply affected young people’s cultural consumption. The whole 1990s were described by Blåsternes as ‘commercialization’ because of the further development of the new economic system and the marginalization of rock music caused by the government’s restrictions, leading the ‘countercultural idealism’ to a ‘more materialistic oriented subject’ (Blåsternes, 2014, p.22). As described Baranovitch, ‘improving the living standard’ became the main aim among people, and ‘relaxation’ was the main pursuit of music consumption: ‘there is no doubt that listening to nonpolitical, sweet, romantic music was the dominant practice in the mid-1990s’ rather than ‘past revolutionary rock’ (cited in Blåsternes, 2014, p.22).

After the year 2000, Rap music in Hongkong and Taiwan had a more direct effect in mainland China with the help of the Internet. In 2001, China participated in the WTO (World Trade Organization) which meant larger-scale international commerce occurring in China, including cultural import and export. ‘Chinese hip-hop’, not pure imitation, started to develop. Breakin-dance, as the visual element in hip-hop culture, firstly became popular, marked by the first ‘CCTV Street Dance Contest’ held by Chinese national television in 2005. At the same time, Chinese Rap music started to grow in mainland China, initially in big cities like Beijing. In 2003, the first hip-hop album in mandarin language was released by a group called Yin Ts’ang (隐藏,meaning ‘hide’), which is formed by three North American and one Chinese members. Since 2005, Rap in dialect began to be popular on the Internet as an expression of local identity, with examples like ‘Dongbei Techan Bushi Heishehui’ (东北特产不是黑社会,Gangsterdom is not special product of the North East), ‘Changsha ce Changsha’ (长沙策长沙,Talking about Changsha city). At the same time, elements of Rap began to appear in popular songs, with examples of songs of Jay Chou and Wilber Pan, which are broadly consumed.

3.2. Commercialization, political control and ‘reinventing rebellion’

The three stages can also be described by the mutual relationships among commercialization, political control, and new forms of subculture for ‘reinventing rebellion’. As Blåsternes described, there are two ways in the development of hip-hop in China: the first way ‘has emerged and been incorporated into the mainstream and commercial market’ (Blåsternes, 2014, p.28), and it’s closely related to the popular, relax-oriented music consumption habits formed during 1990s: the audiences are mainly the consumers of popular music (Chen, 2013); and another way hip-hop has created a subculture resisting mainstream culture. The third way can be viewed as the commitment to the government’s mainstream political ideas.

The ‘commercial type’ is closely related to the ‘consumption of relaxation’ in the second and third stages of development of Chinese Hip-hop. The reality show The Rap of China appeared in the year 2017 is one of the main moments for the commercialization of the Chinese underground Rap music. It was launched by iQiyi, which is one of the largest online video sites in China, was viewed over 2.5 billion times in three months. This represents the large-scale commercialization of Chinese Rap music, as Fullerton commented: “Having been largely underground since emerging in the 1990s, and the frequent target of government censors, hip-hop, it seemed, had finally gone mainstream in China” (Fullerton, 2018).

The ‘subculture type’ are new forms of subculture that appeared in ‘post-Tiananmen China’, which was represented by ‘xinxinrenlei’ (new new human being) ‘linglei’ (alternative) style (Drissel, 2009). According to Drissel, the first one is a description of a kind of young person with the following generational characteristics: being born in the post-Mao era, experiencing the Chinese economic reform and too young to participate in the protest in the late 1980s. They are usually open-minded, indifferent to traditional Chinese values and creating a ‘cool’ persona. However, these characteristics are described as ‘safe cool’ by Wang (2008, cited by Drissel, 2009, p.47), which means “having a ‘partygoing esprit’ that is largely apolitical but engaged in ‘rebellious posturing’”. Sometimes they are viewed as ‘trend pursuers’ and ‘superficial’ because they “relish the materialistic opportunities offered by the new market economy” (Wang, 2008, cited by Drissel, 2009, p.47).

The government’s control or even censorship has always been in the development of Chinese hip-hop. In January of 2018, the States Administration of Press of Chinese government formulated the rule that Chinese television “should not feature actors with tattoos (or depict) hip-hop culture, sub-culture and immoral culture”. An underground Rapper called Bridge from GOSH in Chongqing said that he has his way to resolve this: ‘I see it as a game, just like the TV show was. The country sets rules against me, but I can always find ways around them. This is the fun part of the game’ (Fullerton, 2018). His resolution is “writing lyrics about getting money and generally being a player: my style is just about everyday life - easy and positive” (Fullerton, 2018). It’s totally a kind of ‘safe cool’, which is the characteristic of ‘new new human beings’.

Along with the ‘safe cool’ and ‘unsafe cool’ subcultures, and commercial popular songs, there are Rap groups creating songs supporting the government’s mainstream political ideas. In the early years of 2000, a Rap song called Hello Chen Shuibian was released with the aim of criticizing the then leader of Taiwan and his proposition of independence; In 2016, when Tsai Ing-wen, with a similar political orientation, became the new leader of Taiwan, a gangster Rap song called Red Force for ‘diss’ Tsai appeared. The Rap group called CD Revolution said “we just hate people who want us to break down”, “against the enemies (referring to Tsai) we can use a lot of words to shame them.” They also created patriotic-themed songs, and This is China to “restore the impression you have on my country”, which was promoted by the Communist Youth League. Rap music is also applied into the government’s propaganda. In 2017, People’s Daily, which is the official newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party launched a video that was ‘rap cartoon’ to explain the system of the people’s congress. According to Fung, “music in China has always been regarded as a terrain for political struggle, the authorities had changed from a passive propaganda machine which abhorred popular music to an active, flexible state to absorb, distort and even mold the popular music of the times to co-opt the people and public culture” (Fung, 2007, p.75).

4. Research aim and research questions

The research questions are set into two aspects. First, the form of hybrid-identity construction and the characteristics of the Rap music discourse with the intercultural communication intention, which focus on the linguistic uses and narrative structures of the lyrics and videos. Also, from the intercultural viewpoint, we try to explore whether the communicative discourses for reducing stereotypes and for self-presentation are effective or not.

For the preparation of this article, we have created two general research questions, the first of which concerns the identification of the characteristics of intercultural communication of the selected groups. This research question was later unfolded into two more specific research questions. The first one concerns the understanding of the ways in which these individuals deal with the stereotypes attributed to them, that is, we tried to understand the difference between stereotypes, in the sense that we tried to understand if they reinforce or reduce the stereotype according to the intercultural communication theories. The second research question is the following: How did the intercultural hybrid identity get constructed in the songs? Again, this research question gave rise to two more specific ones. The first relates to understanding how the definition and relationships between “myself” and “otherness” are constructed in the songs. In turn, the second specific research question was materialized in the perception of the impacts of this hybrid intercultural identity that is constructed through the songs of three other cultural models (monoculturalism, multiculturalism, transculturalism).

The general research goal is to resolve the suggested questions using the qualitative methodology (analysis of discourse, observation and interview) to see how the hybrid identity is constructed, including its different forms, in Chinese hip-hop in the intercultural context, in the global youth culture and its communicative effects.

5. Methodology

The main research method is discourse analysis of the lyrics and music videos, and the semiotic narrative method will be mainly applied. According to the method, in every analysis of lyrics and videos, there are three parts which are the manifestation and discourse level, the narrative level and the axiological level.

The first superficial level is the ‘production of the signification’ (Greimas, 1970, p.159), which is the base of a history. We explore the discourse by searching for the actors (roles), the special words, phrases, and cultural symbols and also the mood and tune of the discourse in the lyrics. In the video that tells the same story as the lyrics, we also explore the actors, and how the space and the situation are portrayed. With this exploration, we can localize the core elements of a story and find the main featured roles, answering the questions about ‘use of cultural elements’, ‘types and emphasis of treatment of stereotypes’ (Greimas, 1970, pp.159-160). In this part, the methods of visual semiology and sociolinguistics are added as a complement.

On the narrative level, Greimas constructed an actantial structure in which the main roles and axes in the narration are included. The ‘actant’ is explained as “the one who realizes or experiences the act, independent from any other determination.” (Greimas & Courtés, 1990, cited by Corral, 2015, p.33). So the actantial roles can “be performed by various actors; also, the same actor can play various actantial roles’ (Corral, 2015, p.32). In the structure created by Greimas, three pairs of opposite binaries are set: sender-receiver, subject-antisubject, helper-opponent. This part can help us clarify the relationship between ‘myself’ and ‘otherness’, and the further construction of hybrid identity.

The last and the most profound part is the axiological level, in which the core value of the narration is explored based on the first two parts. Greimas offered a model for analysis of this stage, which is a square of multiple oppositions, contrariness and complementarity relationships (Corral, 2015). This offers us possibilities to explain the ‘in-betweenness’ created by different, or even opposite cultural situations. In this research, lyrics and videos of two songs which are Nomadic by Higher Brothers and Overseas by Bohan Phoenix are emphasized for analysis. Their other songs, like Made in China by Higher Brothers, Three days in Chengdu by Bohan Phoenix, are treated as complementary analysis. We have selected these songs for two reasons: on the one hand, the YouTube promotional videos are among the most popular in the Chinese hip-hop scene ; on the other hand, both songs represent different approaches towards our object of study - intercultural relations in youth music cultures; they also express different and in some way opposite attitudes towards the connection between national and transnational hip-hop scenes.

Our analysis will focus on the lyrics of the two songs chosen. First, we will analyse the level of discourse and manifestation, comparing the text -the English translation-, the analysis of the lyrics (actors, form and tone, main content, subject, mentioned objects, mission, sender and receiver, etc.) and the analysis of the video (actors, situations, movements, appearance, style of montage, etc.). For reasons of simplicity and clarity, we have chosen to present this analysis using a synthetic table. Second, we will analyse the narrative and axiological level, trying to deduce some interpretations from the texts and from its contexts.

6. Nomadic, by Higher Brothers, and Overseas, by Bohan Phoenix

Higher Brothers can be described by their own song called Nomadic, in which the hybrid cultural consumption tastes and desire to go to foreign countries are expressed. It’s a Rap group formed by four boys from ‘CDC Rap house’ which is a local indie Rap music label in a southwestern inland city called Chengdu. They became famous in 2016 for signing and releasing songs with 88rising, which is a New York-based media company and label focused on providing a platform for Asian artists. “They want to bring their Worldwide shit to the entire world” (Telxelra, 2018). This makes them a representative example of the international commercial-oriented mode of development among the Chinese Rappers. Due of this, their videos are more diffused on YouTube, which owns the international users and has been blocked in China. Because of their mode of distribution and creation, their songs have the characteristics of popular Rap music in the U.S, like the ‘trap’ music style and the frequent use of English in the lyrics. Their hybrid identity represents inland Chinese young people who are affected by the international hip-hop flow.

Bohan Phoenix is an indie Rapper who was born in China and was raised in the U.S. since when he was eleven years old. While he grew up speaking English, his Rap is in both Chinese and English. His transnational status and ‘identity crisis’ have been main themes in his music. The presentation on his Facebook page is “too foreign for here, too foreign for home, but still love”. According to an interview (Chesman, 2018), travelling between China and the U.S makes him reflect “where I’m from and who I am, or what I am”, and in his songs, he approaches “what I think of others in my position, not just Chinese immigrants, but immigrants in general”. That’s also how he explained his album called JALA, which means ‘add spice’ or ‘extra spicy’ in his hometown Chengdu, which is famous for spicy food and hot weather. “JALA is an attitude: you are hungry for in spicy and flamboyant ways while always keeping it tasteful” (Chesman, 2018). When he raps this in the western trap style, it’s “a product of the East and the West” and “a product representing a mixture of culture and identities” (Ibid.). His hybrid identity represents the Chinese immigrants with this double self-identity. When they go back to live in China, they are searching for their status in the newly developing Chinese hip-hop scene; at the same time, they have more direct influence on the new Chinese Rappers comparing to western-originating Rappers. This situation can be described by a Bohan Phoenix song called Overseas, in which the hybrid cultural identity and the equal effects of different cultures on people are expressed by “I made a home, overseas. Now that I’m back you remember me?”

7. Case Study of Higher Brothers: Nomadic and transcultural wishes

7.1. Level of discourse and manifestation

Table 1 Analytical synthesis of the lyrics and videoclips

| Translated Lyrics in English | Analysis of Lyrics | Analysis of Video |

|---|---|---|

| [Hook: Joji] I ain’t never stand still, bitch I’m nomadic. Different woman on my bed, that's a bad habit. I ain’t never close my eyes, bitch I'm nomadic. I ain’t tryna be in one place, I relocated. If you see the way the money move, it's nomadic. We just run it through the wire, keep it automatic. We gon’ move it through the shadows, bitch I'm nomadic. I ain’t tryna be in one place, I relocated. | Actor: Joji (The Rapper) Form and tone: objective statement Subject (narrator): me (the Rapper), we (people who are nomadic like the Rapper) Mentioned objects: It’s a self-presentation and there are no evident objects or ‘others’. Refuse: ‘stand still’, ‘close my eyes’, ‘be in one place’. Prefer: ‘different women’, ‘be relocated’. | Actors: All five rappers: MaSiWei, DZ.Know, Joji, Psy.P, Melo; young passengers in a normal old Chinese neighbourhood; A man with a sword who sits alone. Situations: They are in different situations. S1: An old Chinese neighbourhood with narrow lanes, old houses, and wires. S2: Dark underground passage. S3: A Chinese pavilion. S4: an empty old factory Movements: The actors in the neighbourhood look up to see the sky. With the limited view in the lanes, they see other parts of the world (tall buildings, metropolis) and a flying dragon in the sky. Style of montage: The shots move quickly; the sky and the land reverse; the figures move and disappear. Unstable feel. |

| Translated Lyrics in English | Analysis of Lyrics | Analysis of Video |

| [Verse 1: MaSiWei] Wearing body armour to get my boarding pass. Ice on my teeth so they extra white. 90 calls you didn’t pick one, tryna sign me? Need to wait in line. Took a walk on the Rhine River, met a woman called Loreley. She had blue eyes, blonde hair, she sang me a song, what was she saying? 80 days to travel the world, my bodyguard is Jackie Chan Honeymoon with a white girl, in the next city I got another girl. She’s my Juliet, hello you can call me Romeo Pack your things and follow me to the East in my hot air balloon. We wander, we nomadic. I stay far from home, far from her, I’m nomadic. Counting stacks when I’m on tour. You want my life but you can only dream. Gone | Main content: A normal day of the actor: travel and make money Subject (narrator): MaSiWei (the Rapper), we (who wander and are nomadic) Object who receives the narration: you (who dream of the nomadic life but can’t do that) Form and tone: objective statement Mentioned objects: Strong body: Body armour Excellent working skill: many people want to sign him Be famous and rich: with Jakie Chan, counting stacks Western elements: Romeo and Juliet, Rhine River, Girl with blue eyes and blonde hair | Actor: MaSiWei (the rapper), young passengers in the neighbourhood; A man with a sword who sits alone. Appearance: MaSiWei has dreadlocks, wears a gold watch, chain, earrings, and sunglasses. Sometimes he is on a motorcycle, and the driver wears a T-shirt with Chinese characters “Shanghai”. The man who sits alone in a suitcase wears a white shirt, black pants, and a gold chain with a symbol. Movements: MaSiWei is rapping, making hip-hop gestures, and walking on the old street; he also takes self-pictures with the whole view of the world in the sky. The man has an earphone (seems to be listening to Ma’s music); He holds the sword tightly. Situations: Ma is on the old street. When he raps, there are normal passengers (a little boy and middle-aged couples) who watch him. The man sits in an empty old factory Style of montage: The buildings on the old streets are extruded like in the fish-eye lens which can take a picture for a 360-degree scene. The camera shakes a lot. Feel of unreality. |

| Translated Lyrics in English | Analysis of Lyrics | Analysis of Video |

| [Verse 3: Psy.P] I never feel tired, they can’t do what I do The tricks I learned in the years, I’m doing parkour in the violence-ridden district. Trying to find my way out of the slums, only a few survivors. Follow my steps, my desire to live can protect you. Shoot the energy into my veins like speed, I got all the attention. Eye-catching, I’m unforgettable ay You ain’t on my level so don’t let me catch you slippin’ Don’t blame me for not reminding you, got that ridiculous look in your eyes. Mama, you said you like Paris, go with me next time, don’t stay at home. I’m used to the loneliness and I feel great, no one can tie me down. But I’m still filled with anger, I’m used to going out at night | Main content: The struggle that the Rapper did for the nomadic rich life. Subject (narrator): Psy.p (the Rapper) Object who receives the narration: self-presentation; ‘mama’. The ‘others’ were the competitors who were beaten by the Rapper. Form and tone: declaration Objective (mission): being rich and travelling the world with his mother. Sender and receiver of the mission: the rapper himself Helper: the ‘desire to live’ and the ‘energy in veins’ of the rapper himself. Mentioned objects: The difficulties when fight for success: doing parkour in a violence-ridden district; find the way out of slums; Competitors’ threat. The difficulties after success: loneliness | Actor: Psy.P (the rapper), his partners. Appearance: Psy.p has dreadlocks. He keeps his clothes on, and the tattoos appear. Two girls wearing heavy makeup appear. Movements: The rapper is rapping, making hip-hop gestures, and walking Situations: They are in an underground passageway with vague, purple light. Style of Montage: Only Psy.p, who is in the middle, can be seen clearly. Others around him are like moving shadows (metaphor of his competitors). |

Source: the authors.

7.1. Narrative and axiological level

The narration describes the Rappers’ ideal life which is ‘nomadic’ and their struggle to get that. On the discourse and manifestation level, we were able to see some featured actors: the Rappers; the Rappers’ competitors; people who want the nomadic life but can’t do it; different (foreign) girls; ‘mother’ and ‘she’ at home. The first verse, fourth verse and the hook of the lyrics are the presentation of the object: living in a nomadic way, being on the move, and never stopping. In the second and third verses, the ‘breakdown’ or ‘imbalance’ was mentioned: the first is ‘living in the slum’ representing the pressure of living; the second is ‘staying at home’ which leads to conflicts with people around; and the last is the single information source. These ‘breakdowns’ lead to the ‘action’: to change this life, the Rappers (Higher Brothers) are the subjects of condition and action, and also the receivers of mission. In terms of the sender of mission, both the Rappers and the global situation of the world play the role: Higher Brothers themselves tried to fulfill the task, and the round, connected world also gave them opportunities to travel. In the execution of the mission, the first main helper is the rappers’ desire for life; the second main helper is the Adidas footwear since it’s an advertisement for the brand. As for the opponents of the mission, this role doesn’t evidently exist. Some actors who are likely to be the opponents, like the competitors or the conservative family members, aren’t quite the barrier for the Rappers in these songs; they are just people who are disliked or disdained by the Rappers. Even the ‘mother’ becomes the beneficiary of the action: ‘Mama, you said you like Paris. Go with me next time, and don’t stay at home’. Therefore, in all the songs, the Rappers themselves play a great part of the roles; at the same time, it’s a narration without opponents.

The Chinese cultural elements don’t appear frequently in the lyrics and videos; at the same time, a great part of what is depicted are subjective cultural elements like ‘CCTV’ (Chinese Central Television) in the second verse and the old Chinese neighbourhood in the video. The dragon metaphor in the video can be treated as a classical Chinese legend, which is an objective cultural element; but the image of the dragon in the video is not in the traditional Chinese style, but a dinosaur, which is more familiar to western audiences.

Several foreign elements appear in the songs, like western girls and tourist attractions. These elements are in the role of ‘object’, which is the aim of the mission, and the core elements in the Rappers’ ideal life. However, though the Rappers express their desire for these objects, the attraction of these isn’t ‘being western’, but ‘the result of moving and communicating’. In the verse 4, the ‘beautiful Tibetan Plateau’ is also treated as a dream destination for the Rappers. Hence, in the cultural aspect, the ‘otherness’ and the ‘Chineseness’ isn’t evident in this song. The cultural integration can also be seen from the movement of space in the video. The fish-eye lens is used, which lead to the full view of the world, meaning the little limits among the countries and spaces.

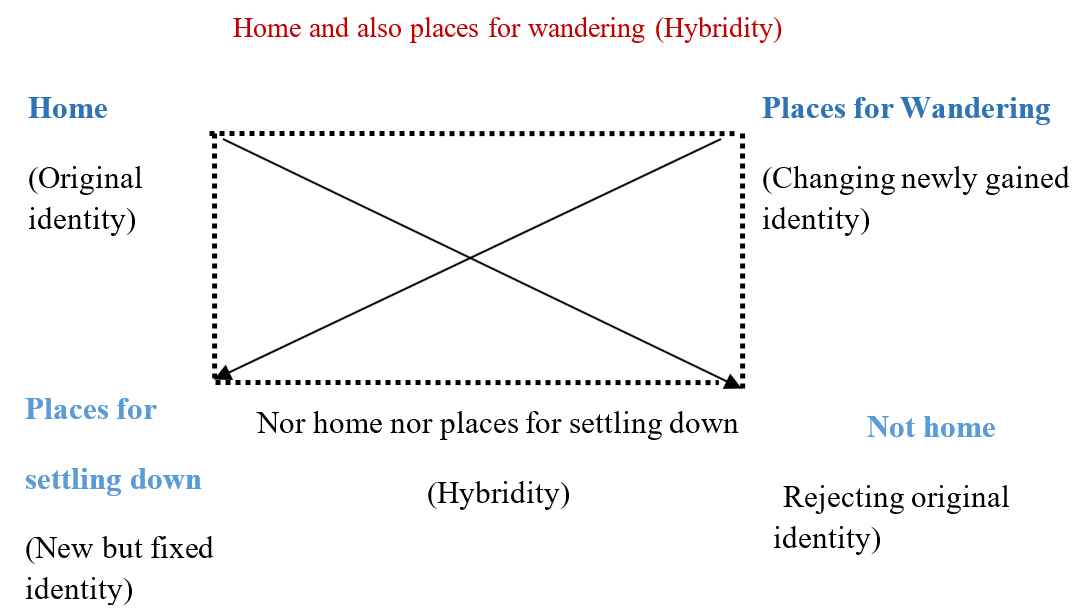

According to the four models of culture, the song can be explained by the fourth ‘transculturalism’, which means little difference between cultures and total integration. The characteristic of people in this culture is ‘moving, changing’ and ‘being the same’. So, the Rappers discuss the topic of the limits of different cultures: being nomadic is breaking these limits. Therefore, in the axiological level we can explain the integration between ‘home’ and ‘places for wandering’. If we analyze the song combining the lyrics and videos, the rappers are creating concepts of ‘home and also places for wandering’, and ‘neither home nor places for settling down’.

8. Bohan Phoenix: searching for resonance by self-presentation

8.1. Discourse and manifestation level

Table 2 Analytical synthesis of the lyrics and videoclips

| Translated lyrics | Analysis of lyrics | Transcription of Videos |

|---|---|---|

| Hook Cause I was born, overseas Then my mama took me overseas I made a home, overseas Now that I’m back you remember me? Cause I was born, overseas Then my mama took me overseas Now that I’m back, finally Do it for me and my family | Main content: Brief narrative context of Bohan’ life: left China, went to America, Come back to China Actors: Bohan Phoenix, Mama | Actors: Bohan Phoenix, wearing a white T-shirt, golden chains, kerchief with leopard print Situations: Bohan plays piano in front of a screen. The playing images on the screen are not clear and change quickly. Only some fragments can be seen: sky view on the plane; sea and waves; western people who are rapping; girl’s eyes. Movements: Bohan is playing the piano. Style of montage: The image is black and white until the next verse comes; The images on the screen change a lot and aren’t clear, which are similar to the images in dream. At the same time, Bohan don’t move, meaning that the situation changes. |

| Translated lyrics | Analysis of lyrics | Transcription of Videos |

| When I come back to Chengdu, my family is not accustomed to my tattoo. I can’t blame them for not understanding the reason why I like it so much. It’s not easy for them to accept Western culture. Slowly, slowly, everything is slowly coming. They don’t understand my words. They said ‘I didn’t understand’. But you know this feeling right. It doesn’t matter if you don’t understand it. I keep chasing childhood dreams. I chased after a long time. I broke my leg and I started to fly My Phoenix's wings burn into ash. | Main content: Life and difficulties when Bohan moves back to China Actors: the rapper; family; ‘he’(mom’s husband); ‘they’. Object who receives the narration: self-presentation Form and tone: objective statement Mission: Adapting the new life and Chasing the childhood dream. Sender and receiver of the mission: Bohan Phoenix himself. | Actors: Bohan Phoenix Situations: Bohan plays piano in front of a screen. Style of montage: The image becomes colorized (meaning the hope of real life). The images on the screen become the sea and moving waves. |

| Translated lyrics | Analysis of lyrics | Transcription of Videos |

| No matter the language I spit in the verse I make sure I know what I’m worth The powers preserved within all these words Make certain I thrive on this Earth The noun and the verbs are never rehearsed They come to me natural as birth I am the last, I am the first Bury them deep in the dirt If they violate the chosen one My skin tone it shines like the golden sun I learned how to punch in the very East But in the West, they hold bigger guns Strap on my boots and I learn to run I got the juice, and I got the heart Pumping it like when the engine starts Haters get burned like them tire marks I swear to God | Main content: Presentation of Bohan’s talent of rapping, and the relationship with his experience Actors: the rapper Object who receives the narration: self-presentation Form and tone: Announcement Mission: Being a good rapper. Mentioned objects: learn to punch from the east; the crisis in the West push him to learn. Rap is a form of expressing himself. | Actors: Bohan Phoenix, various middle-aged women with clothes for every-day wear and silk scarves (ceremony in daily life) Situations: Bohan plays piano, and the piano catches fire. Movements: Bohan is playing the burning piano. The ladies come from the two sides of the piano and begin to dance the ballroom dance around Bohan. Style of montage: The main role in the view changes, first it is Bohan, later Bohan is behind the fire, and the dancing ladies are in whole view. |

| Howie may be angry because I'm not obedient, I’m still trap. Mom may be angry because I'm not obedient, I’m still rapping. But I know it, so I still swag. Clear road in my mind, this is my path. | Main content: People don’t understand Bohan’s intention of rap. | The ladies continue dancing and make a final gesture. Bohan stands up and comes to the centre. |

Source: the authors.

8.1. Narrative and axiological level

The narration describes the Rappers’ life when he decided to go back to China: his difficulties, hesitations, and persuasions to himself. According to the discourse and manifestation level, we can see some featured actors: the rapper; the family; ‘they’ (people who don’t understand him). The narration is divided into three parts: a brief presentation of his previous experience; going back to China and trying to adapt to the new life; trying to persuade himself that both coming back and keep rapping are correct choices. The main aim of the whole story is finding the rappers’ identity and the balance of the new life.

The ‘breakdown’ and ‘imbalance’ start from his experience ‘overseas’, which can be seen in the question ‘now I’m back do you still remember me?’. This reflects that he experienced an identity crisis when he went back to China from overseas: people don’t know him and he is alone. Problems are developed in the second verse: he can’t speak Chinese well; the family doesn’t like his tattoo nor western culture. Overcoming these problems to establish his new and own identity is the main ‘mission’ for Bohan Phoenix. In this narration, he plays a lonely role, because nearly any other roles exist in the lyrics: he is the subject of action, sender and also receiver of the mission. The role of ‘helper’ isn’t a real person, but ‘Rap music’ or ‘keep rapping’, which is also done by Bohan Phoenix himself; and there are a lot of opponents, people who don’t understand him: family members, most importantly his mother, and people around him. Therefore, we can see that the construction of the narrative structure creates Bohan’s lonely figure with much pressure, searching for his identity.

In the lyrics, the only helper and the hope for solution is struggling, studying gradually, and keep rapping. But in the video we see another role: the dancing ladies. Ballroom dancing can be seen as the symbol of internationalism of China during 1950s and also after 1980s, when the generation of Bohan’s parents and grandparents were young; at the same time, as this generation retired, dancing together in the community has become a popular activity among the middle-aged ladies in China. Relating Bohan’s experience and his relationship with his mother and grandma, we can treat the dancing ladies as the metaphor for family, especially the love given by his mother and grandmother, who are not with him now. Bohan’s stage name is ‘Bohan Phoenix’, in which the ‘Phoenix’ stands for the fire and reaching nirvana, according to the legend. In the video, the piano is on fire; the ladies stand around it and Bohan leaves it to stand in the center. We can understand that it’s a metaphor for ‘growing up’ with love.

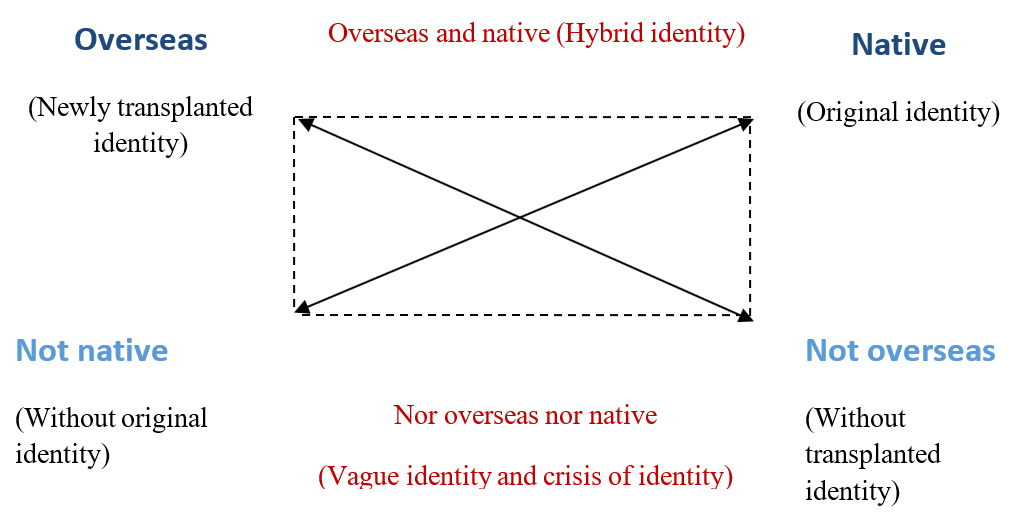

Neither the video nor the lyrics present an answer to how Bohan deals with the problem. What we see more are his real difficulties, crises, and confusions. The main source of his problem is being ‘overseas’. So, on the axiological level we can explain the narration by ‘native’ and ‘overseas’, because Bohan’s experience is creating concepts between these two and searching for a balance.

9. Discussion and conclusions

The cases of Higher Brothers and Bohan Phoenix represent two different types of hybrid identity constructed by different intercultural intentions. The situation is similar to the description of the theory of ‘pull and push’ of migration proposed by Ravestein (cited in Cuamea, 2000). According to the theory, the choices of ‘push’ or ‘pull’ of international immigration depends on various economic elements of the country: because of the ‘economic backwardness’ in the developing countries, the ‘push’ or ‘expulsion forces’ appeared; at the same time, there are attractions in industrialized countries such as “higher wages, employment, better welfare”, etc. (Cuamea, 2000). In the case of this research, the influences of surging economic development of China on young people are evident: on the one hand, former immigrants like Bohan Phoenix are coming back; on the other hand, this gives inland young people opportunities to go out or ‘have a nomadic dream’.

At the same time, this hybridity or combination of simultaneous ‘push’ and ‘pull’ expressed by the mainland Chinese Rap music of the post-2008 crisis generation reveals that the cultural elements affect young people’s lifestyles. Though Higher Brothers and Bohan Phoenix embody different stereotypes (“Chinese young people aren’t worldwide” for Higher Brothers, “being a foreigner but not Chinese” for Bohan Phoenix), the cultural gaps are evident. That’s why the intercultural communication has become the main topic for discussion in both groups. This macrolevel hybridity leads to the rappers’ hybrid identity explored in this research: ‘home and also places for wandering’, ‘nor overseas nor native’. All of them reflect the vague, re-constructing identity and the possible resulting crisis, which are their ways of expressing authenticity.

To reduce the stereotypes, Higher Brothers tried to persuade basing on common stereotypes about China (don´t move, can´t rap well), by combination of ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ cultural elements (Bennett, 1998). However, they continually emphasized the similarity among Chinese young people and others, like the full-view world in the video of Nomadic, which means the world connection. The difference between Higher Brothers and Bohan Phoenix in intercultural communication is that Bohan’s objects of persuasion are both people from China and from other countries: because of his identity as a Chinese immigrant who lived in the U.S., sometimes he tries to hide his foreign identity (language, previous achievements in the U.S., etc.) and tell Chinese audiences about his desire for acknowledgement by Chinese people.