Introduction: Zwischenstadt

In a particularly strange year where we find ourselves in a situation quite complex to explain and live in, we might recall the Zwischenstadt, where, as Thomas Sieverts (2003) puts it, “today’s city is in an ‘in between’ state, a state between place and world, space and time, city and country” (p. x). A space___between two realities: a suspended time, happening in the spaces we hardly notice, fragmented. Rather than disperse and diffuse, fragments need to connect back more than ever.

Around the world, many of these spaces are trapped between physical realities, like an urban sandwich. This state of suspension is an opportunity in the gap of time. For something like this to happen, multiple decisions, specific to their area of location, occur at individual and collective levels. Without an exit or purpose, these spaces become icons of the forgotten. For those who observe or transit through them, these urban voids are enclosed containers of unknown stories lost over time.

Human beings are curious by nature. When we walk down a street and someone has an entrance door open, we tend to look inside. The unknown, private, or alien, the abandoned areas, alleys, or common walls are all interstitial spaces that capture our attention. We identify ourselves with them because deep down we are in constant search for something. Those interstices (Lévesque, 2013, p. 23-24) share characteristics of indefiniteness where we cannot see the entire picture, but we begin to think about utopian possibilities for these interruptions to be knitted back into the city.

Many concepts help define these spaces within the city, but presenting them all would be an infinite journey. From their ambiguity we can imagine possible futures and interpret the best intervention role for each site to ensure its continuum.

Cataloguing urban space: Can the indefinite be defined?

If we wandered through the city, we all might encounter unnoticed buildings, derelict lots, or spaces with no clear past which call our attention.

Often catalogued as neglected and forgotten, scholars and planners have also referred to these spaces with innumerable terms like the German Stadtbrachen (urban fallow lands, or undeveloped lands left to themselves for some time); brownfield or vacant lots, both specified by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA); and as residual spaces or terrain vague, two terms stated by Ignasi de Solà-Morales i Rubió (1995, p. 123). Moreover, we could include abandoned space, from Karen Franck (2014, p. 154); non-places, by Marc Augé (1995); no-man’s-land, from Carla Corbin (2003, p. 16); fallow or Third Landscape, by Gilles Clément (2011, p. 278); derelict land (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister - ODPM, 2006, pp. 41-42); and Kevin Lynch’s open space (1991, p. 396). There could also be a subcategory belonging just to ruins, as seen with Tim Edensor (2005, p. 4), and buildings that stand still in time. They refer to the empty, abandoned buildings in a state of decay. To establish a defined typology, subcategories of abandoned buildings and ruins could be placed inside the category of terrain vagues, because a ruin is a place left behind as well (Beasley-Murray, 2010, p. 212), and it can be reimagined in multiple ways.

We could go even further into other languages where terms have slight changes in what they involve. Some designations are terrenos baldíos, in Spanish; freiräume and leerräume, both in German; or vazios urbanos in Portuguese, as mentioned by Cláudia Taborda (2007, pp. 126-127). As Gil Doron (2008) mentions, these spaces have received a “multiplicity of names, and some of their meanings, show the difficulty in defining those spaces” (p. 203). Ultimately, each case of analysis would require a specific category and this multiplicity makes it hard to establish a concrete parameter.

But can the indefinite be defined? Or why do we always try? In any language, the term terrain vague encompasses the idea of the undetermined, covering ‘uncertain spaces’, which seek to be set into specific parameters, representing unproductive land which cannot be typecast. In contrast, vacant terrain (Office québécois de la langue française, 2001) refers to land with no form of occupation, ready for construction.

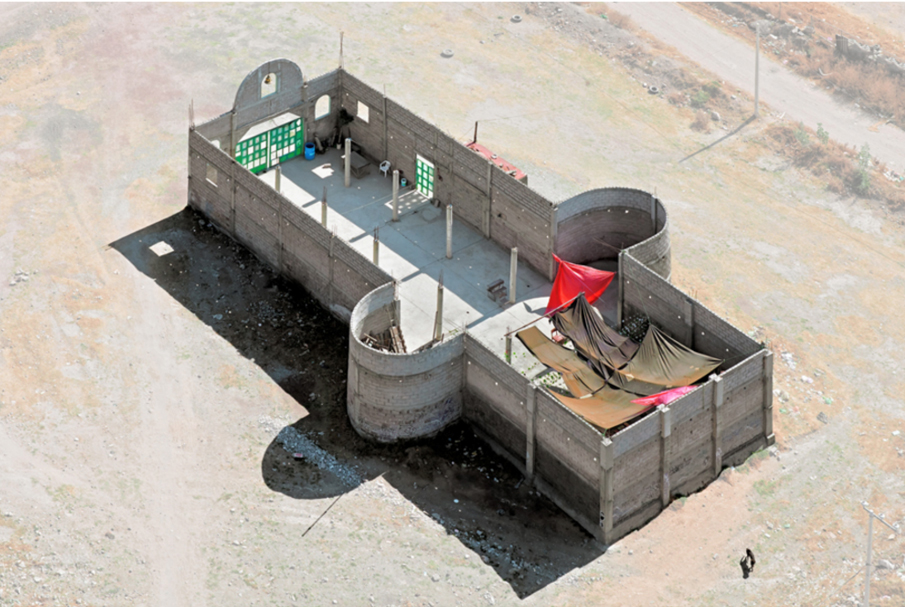

© Juan Carlos Calanchini González Cos. Creation based on Google, Imagery / INEGI, 2020.

Figure 1 19°18’14’’N 99°10’40’’W / 19°18’16’’N 99°10’32’’W / 19°18’20’’N 99°10’27’’W, Mexico City, Mexico, 2020

Ignasi de Solà-Morales (1995) first attempted to talk about the unoccupied, abandoned, or underutilized spaces which are often overlooked (Figure 1), by giving the concept terrain vague more focus in an effort to understand their complex nature as part of the city’s fabric. He classified them as “apparently forgotten places where the memory of the past seems to predominate over the present (…). Obsolete places in which only certain residual values seem to be maintained despite their complete disaffection of the activity of the city (…) they have become areas in which it can be said that the city is no longer there. Its edges are lacking in effective incorporation, they are interior islands emptied of activity, oblivions. and remains (…) outside the urban dynamic. Becoming uninhabited, insecure, and unproductive areas” (p. 119).

If we consider these unproductive areas, or terrain vagues, as urban voids, Sergio Lopez-Pineiro’s (2020 ) provides us with the argument that “despite their marginality-or rather, precisely because of it-urban voids are spaces engaged in temporary processes of abandonment and appropriation, simultaneously empty of regulated urbanity but also filled with unexpected possibilities” (p. 15). The term void can sometimes be confused with emptiness, but for the purpose of this paper, we are going to take Lopez-Pineiro’s (2020) clarification: Void is “not used [in this case] to imply that these spaces are emptied of everything (…) [they] are emptied of the value that is associated with the prevailing ideology of cities as places of capital accumulation. But this emptiness (of capital, real estate value, efficacy, or production) is precisely what enables other sensibilities and opportunities to emerge” (p. 17). These remnant spaces let us imagine an imprecise world and identify the uniqueness within ourselves, not limited to what the city imposes on us. For this purpose, I then propose to continue to refer to them as such.

Michel Foucault: heterotopias as counterspaces or spaces of other

Michel Foucault gave an interesting take on the topic of the fragmented in Des espaces autres (1967/1984), when he said that there are spaces called “heterotopias,” which are related to all other spaces, each one with a specific function, but “simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted. Places of this kind are outside of all places” (p. 3). These are real, existing, everyday spaces that can be classified as “spaces of other” (p. 3), or as Sandra Loyola Guízar (2017, p. 102) would call, spaces of “crisis and deviation” (p. 102), where one can “carry out other actions” (p. 102), just as a “counterspace,” “because they cannot be classified as public, private, occupational or recreational” (p. 102), and “where actions that contradict the normality or the everydayness of an apparently logical, ordered and progressive world take place” (p. 102). How does one think about these spaces?

Some can be juxtaposed into one, others have several permeable layers of time, or isolate themselves. In this sense, Michel Foucault (1967/1984) stated that “we are in the epoch of simultaneity: (…) of juxtaposition (…) the epoch of the near and far, of the side-by-side, of the dispersed” (p. 1). And, I would add, of the fragmented, because, in his own words, heterotopias are “the disorder in which fragments of a large number of possible orders glitter separately in the dimension (…) in such a state, things are ‘laid,’ ‘placed,’ ‘arranged’ in sites so very different from one another that it is impossible to find a place of residence for them, to define a common locus beneath them all” (Foucault, 1970/2005, p. xix). He also added that (Gaston) Bachelard’s work has “taught us that we do not live in a homogeneous and empty space” (Foucault, 1967/1984, p. 8), and that these fragmented spaces could easily have “a function in relation to all the space that remains” (p. 8). Could Foucault be talking about these places as reflections of our human persona and way of living? In this sense, Loyola Guízar (2017) argues that “around these places of other, endless prejudices, stigmas, and imaginaries are built, and through these prejudices and ideas, we try to understand those places and try to understand ourselves; producing in this process devices of socio-spatial exclusion” (p. 104).

One can only imagine all those unnamed spaces which connect with the named spaces we know more about: houses, offices, supermarkets, among others. Both categories can become chances for a conjectural human response to a speculative urban realm. We should engage with those “unpleasant” spaces, and locate them in the division of utopias, to think about the possibilities that may arise, or in the heterotopias, where we know they exist but cannot pigeonhole them into a specific category because of their complexity.

We can view them as placeless spaces suspended in time (Figure 2), enclosed and surrounded with mirrors reflecting upon themselves, like echoes, not being able to understand their place within the context in which they are inserted. Sergio Lopez-Pineiro (2020) argues that “by allowing unregulated and unplanned spontaneous events to take place in an urban void, different insights can be derived depending on how the space is used. For this reason, urban voids act as mirrors reflecting the society we are and the one we want to be” (p. 153), just like the utopia of the mirror mentioned by Foucault (1967/1984) as being a heterotopia (p. 4 para. 1). The space gets reflected in the mirror occupying the place it knows it is occupying, but seen from another place, realizing what it is and where it is located: the real connected to the unreal surrounding space. To be perceived, it must pass through the virtual point that is over there, somewhere else.

Exposing spatio-temporal structures: Gordon Matta-Clark and the Conical Interest project

For the inner workings of remnants to move people and establish a connection, what might be done is to read those sites profoundly, study their past, make a temporary intervention, and explore possibilities for their future use. This requires observation and what Michel Foucault (1967/1984) called a “systematic description (heterotopology) that would, in a given society, take as its object the study, analysis, description, and ‘reading’ (as some like to say nowadays) of these different spaces, of these other places. As a sort of simultaneously mythic and real contestation of the space in which we live” (pp. 46-49). Artists and architects should work together to dissect these sites full of potential and propose their activation as an effort to avoid their permanent state in time, preparing their return to the public realm.

This link between architecture and art, regarding the topics mentioned so far, brings to mind one of the most significant exponents of interventions in neglected elements: Gordon Mata-Clark, American architect [1943-1978], who worked in the ’70s primarily with urban void appropriation. His œuvre focused on undoing and doing, but he considered most of his works as “non-architecture” (Matta-Clark, 1974a, cited in Moure, 2006, p. 172), experimenting with limits of space, emptiness, and public perception. Although most of his body of work was demolished as part of the interventions themselves, they will never be erased or forgotten from the collective memory thanks to the vast collection of videos and photographs, as well as a few physical fragments of some of his interventions, with which he carefully documented everything.

“‘In regard to the many condemned buildings in the city that are awaiting demolition,’ Matta-Clark (1977) wrote, ‘it seems possible to me to put these buildings to use during this waiting period (…) As an artist, I make sculpture using the by-products of the land and people’” (cited in Lee, 2000, p. 73). An analogy in music would be the symbol of silence on a score, an opportunity to pay attention to the pause between notes. Thus, working with remnants allowed him to create a different discourse of inner and outer space, of places not forgotten but remembered. Something between public and private space, being and not being, “surely, Matta-Clark’s projects contend with the timeliness and untimeliness of things-the past and the present of buildings, garbage, cities, people, and the question of futurity they open to (…)” (Lee, 2000, p. 214). The richness of strangeness and uncertainty.

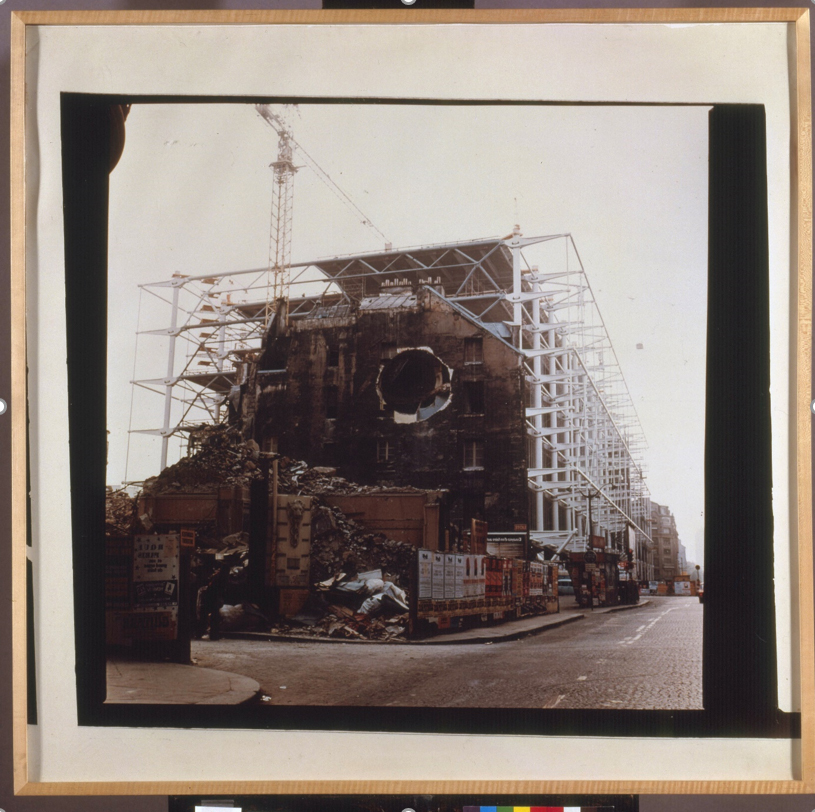

One of his more articulated projects must be Etant d’art pour locataire - Conical Intersect (Figure 3). The project started with an invitation to develop an intervention for the ninth edition of the Paris Biennale in 1975, and upon his desire to transform “an abandoned structure slated for demolition into a work” (Matta-Clark, 1975, cited in Lee, 2000, p. 169), he was authorized to work with two buildings from the 17th century, in the plot adjacent to the Beaubourg Museum (now Centre Pompidou), being built by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano in a parking lot adjacent to decayed vacant landscapes merging to reactivate the entire district. “The site at 27-29 rue Beauborg was two modest town houses built in 1699 (…) among the last left standing in the plan of modernizing the Les Halles-Plateau Beabourg district” (1975, cited in Lee, 2000, p. 169).

Matta-Clark, Gordon (1943-1978) © Artists Rights Society (ARS). Color photograph, 101.6 x 106.7 cm. AM1991-48(4). Repro-photo: Philippe Migeat. Location: Musee National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France. Photo credit: Digital Image © CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. ART165256.

Figure 3 Untitled: Detail (27-29 rue Beaubourg), 1975

He played with the palimpsests inscribed in the site, “certainly aware of how charged a site it was, perhaps the most appropriate backdrop for his building cuts. More than any of his other works, the Parisian site neatly illustrated the tension between narratives of historical progress-embodied in the construction of the Centre Pompidou-and the destruction of a historical site that is a prerequisite for progress” (1975, cited in Lee, 2000, p. 169). By drilling a conical hole through the two buildings, he created a spatio-temporal void, where light came into an obscure interior, bringing air with it, and resulting in an experimental spatial revelation.

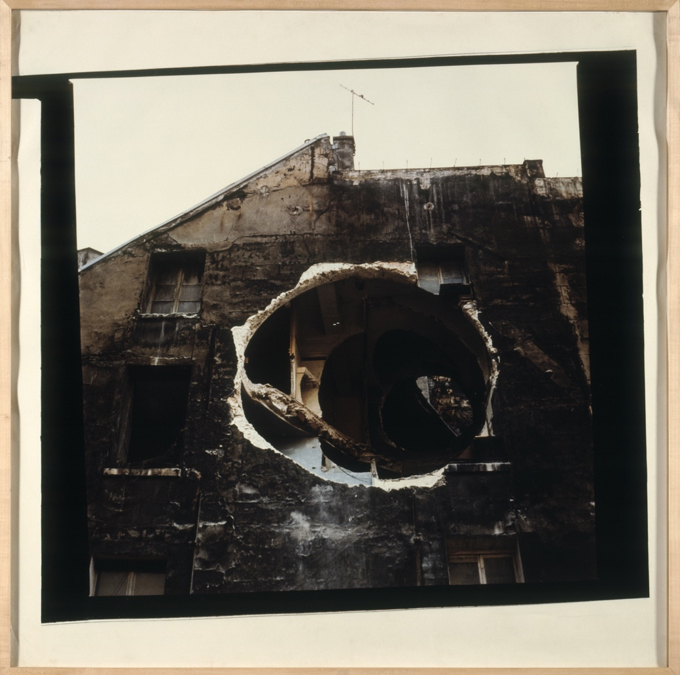

As a clearer possibility for urban dialogue, the incisive building cuts exposed internal space in a strategic location of the city to the wider public walking down the street, looking at the work of art being made in real time, and the new building rising behind. Revealing the interior was an erasure of collective memory for the passers-by. The “cultural tension between loss and transformation” become, just as Peter Muir (2011) argues, “its own inevitable erasure (its own self-effacement), emblematic of memory, loss, condescension and contradiction, artistic and ‘political’ naivety, confusion and the inherent powerlessness of communities over the possession and use of the land” (p. 174). A complex fragment in time eclipsed by the construction of the Centre Pompidou (Figure 4), which would bring a new cultural movement and dynamics.

Matta-Clark, Gordon (1943-1978) © Artists Rights Society (ARS). Color print, 101.6 x 106.7 cm. AM1991-48(5). Repro-photo: Philippe Migeat. Location: Musee National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France. Photo credit: Digital Image © CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. ART165255.

Figure 4 Untitled - Detail Conical Intersect, series of 5 color proofs, 27-29 rue Beaubourg, 1975

Matta-Clark’s spatial-temporal interventions allowed the local community to see and recognize them as living elements and give a new meaning to what otherwise would have disappeared. Through his cuts, Matta-Clark left the viewer with a carte blanche to interpret the connections with fibres in the deep grounds of their mind. The transformative effect that art and architecture have on people’s lives and well-being can enhance these elements’ intrinsic characteristics.

Collective memory: Connecting with the voids of a city

The Anarchitecture group to which Gordon Matta-Clark belonged showed an elusive, critical, and alternative attitude towards physical and social aspects of architecture. They were, as Matta-Clark (1974b) himself puts it, “thinking more about metaphoric voids, gaps, leftover spaces, places that were not developed (…) places that are just interruptions in your daily movements. These places are also perceptually significant because they make a reference to movement space” (cited in Lee, 2000, p. 105).

A city is non-linear, like heartbeats on a vital signs monitor, with both active and critical points constantly changing. When there is any interruption, it stops working properly, and that is when an intervention is required. These “interventions are insertions or assemblies constructed within spaces; resignifications and rearrangements that allow to reevaluate the object, while the context in which it is developed gets interrupted or adapted” (Calanchini González Cos, 2016, p. 155). Taking the previous analogy, “a place that is an ‘interruption’ or a ‘movement space’ is a liminal space, unbounded by the restrictions of real estate. ‘Leftover’ because not legislated for use, these spaces refuse ownership because they are illegible, ambiguous, kinetic even” (Matta-Clark, 1974b, Lee, 2000, p. 105).

Cities and bodies also have scars or marks, characterized as tattoos or cosmetic layers that mark the passage of time. These inscriptions-as if tearing the territory apart-are architecture. I suggest to call them remnants of a city: like a trace of memory difficult to erase, but almost impossible to define. To exemplify this within the context of Conical Intersect, Peter Muir (2011) mentions that the object as a reference and a beacon in a communal social setting sparks “powerful social memories” which, in turn, “facilitate a reading in terms of these social memories, not in terms of the literarization of the conditions of life’s immediacy, but of the void left behind by its loss.” There, he states that “the beholder’s emotions are, in a process of transference, mapped and projected elsewhere” (p. 181). All these acts leave a mark in the collective memory while building a new perception.

Most European cities, like Berlin, have suffered from literal war wounds, and transformed over time. Before the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, there was a clear and almost permanent division marking what was happening on both sides of the same territory. The Wall did not fall completely but by pieces: isolated excisions, unwoven, fracturing the unclear reading. New stone blocks are set on the ground, showing where the wall used to be, which is now a street. There are segments of the Wall with empty lots next to it, or a square, or a building. It is like half a tattoo where you cannot see everything, but different ways of seeing that same act, object, or scar.

Here, it is not about getting rid of the voids, but connecting with them. For that to happen, it is important to focus on the physical aspect of city reconceptualization. Sergio López-Pineiro (2020) described urban voids as “both failures of collective will and becomings of individual spontaneity. As potentials, they become places of seclusion that can help unleash people’s individual imaginations” (p. 149).

How, then, can we achieve an open public space by reconceptualizing the void, which is usually characterized by being enclosed to the city and to itself? Trying to occupy an urban void means opening up. The government and city planners need to be mindful of certain zones which need redevelopment more constantly than others. Not surprisingly, in some cities around the world only the communities living there care for them. A city can be reorganized through a physical interaction of elements from the cultural sphere, mixing art, architecture, design, and sociology to be part of a cohesive experiment by resignifying critical spaces and objects.

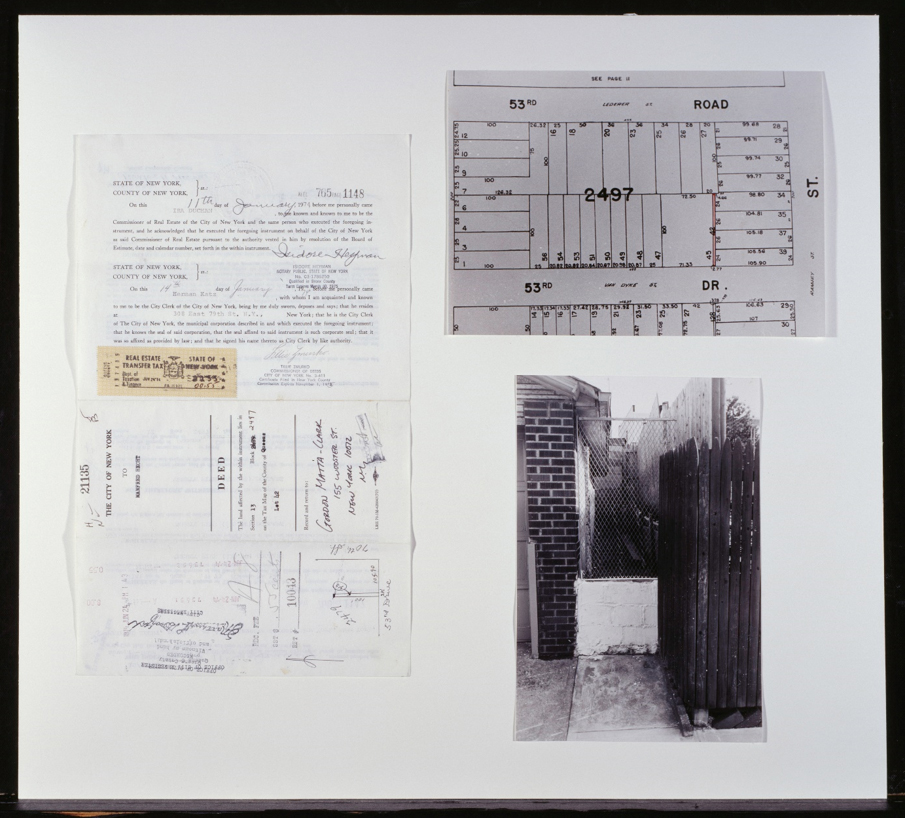

This is something Matta-Clark tried to explore with the Reality Properties: Fake Estates project (1973), by purchasing “‘surplus land’ [in Manhattan and Queens], through auctions sponsored by the City of New York. Better known as ‘gutterspace’ or ‘curb property,’ these (15) tiny slivers of land (Figure 5) were actually ‘leftover’ parcels from lots drawn by architects and city planners for buildings and property. They had now become city property because their owners had failed to pay taxes, and were available for around $35.00 apiece” (Lee, 2000, pp. 98-99). Matta-Clark recognized them as abandoned spaces in an uncommon urban dynamic. For him, “that which cannot be used, that which is inaccessible and therefore non-productive or workless, may also be a potential source of social space” (2000, p. 104). When he bought them, they were appreciated even without being able to be adequately used because of their dimensions, physical conditions, and impossibility of access. “Something that can be owned but never experienced; certainly not occupied; the strangeness of existing property lines” (p. 103).

Matta-Clark, Gordon © Artists Rights Society (ARS). 1974 (posthumous assembly, 1992). Photographic collage, property deed, site map, and photograph. Framed photographic collage: 10 x 87 3/16 x 1 3/8 inches (25.4 x 221.5 x 3.5 cm); framed photograph and documents: 20 5/8 x 22 5/16 x 1 3/8 inches (52.4 x 56.7 x 3.5 cm). Purchased with funds contributed by the International Director's Council and Executive Committee Members: Edythe Broad, Elaine Terner Cooper, Linda Fischbach, Ronnie Heyman, J. Tomilson Hill, Dakis Joannou, Cindy Johnson, Barbara Lane, Linda Macklowe, Brian McIver, Peter Norton, Willem Peppler, Alain-Dominique Perrin, Rachel Rudin, David Teiger, Ginny Williams, and Elliot K. Wolk, 1998. Location: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY, USA. Photo Credit: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation / Art Resource, NY. ART457210.

Figure 5 Reality Properties: Fake Estates, Little Alley Block 2497, Lot 42, 1974

Sharmin Bhagwagar (2018) mentions that Foucault illustrates in The Order of Things, through the categorizations of space, how language functions as a tool of authority. In this sense, I suggest that Matta-Clark’s intention was to organize what cannot be organized. For Elizabeth Grosz (1992), the urban area, or the city, is a “network which links together in a disintegrated way a number of disparate social activities, processes and relations, with imaginary and real spaces” (cited in Fontana-Giusti, p. 130). All these plots, completely surrounded in the growing city, can accommodate models not found in that same area by experimenting with citizen participation to turn them into essential public spaces, which can be viewed as purposeful; this, in turn, encourages social interactions. For Bhagwagar (2018), “the act of acquiring these spaces, besides injecting them with voice and identity as deviant spaces, could also be considered a metaphorical reference to Matta-Clark’s physical cuts” (para. 5). In these slivers Bhagwagar (2018) sees Foucault’s heterotopology, where “radical anti-architectural gestures generate questions on state-controlled distribution of property, the growing concerns of modernity, and the inefficacy of post-modernists’ responses to these problems” (para. 2). Matta-Clark attempted to catalogue and expose the almost-impossible use of these slivers-these “in-betweens”-by connecting them as a network of spatio-temporal moments.

In-conclusions: A state of suspension

What happens in the space___between what is and what can be? Almost anything is possible, but how can we be able to define something that cannot be defined? A conclusion on a subject as vague as this can be dangerous, because defining something implies leaving out what is beyond the limit of the definition itself.

Here we are not trying to define what we cannot name. For Thomas Sieverts (2003), “what is needed in this situation of uncertainty…is a maximum degree of openness” (pp. 160-161). In this sense, James Corner (2001) stated that “to name it is to claim it in some way” (p. 124), and Sergio Lopez-Pineiro (2020) agrees, stating that “in order to retain its openness, marginality, and indeterminacy…they must remain unnamable” (p. 19), and the space must remain untouched, until we explore its inner qualities. An unquestionable point is that, although different, these remnants share similar characteristics, which is why many related terms exist, but with conceptual variations corresponding to specific language and sites.

Sieverts (2003) showed that “our present view of urban development is shaped by the concept of uncertainty” (p. 159). It is precisely uncertainty which brings the potentiality and openness he mentions, to give light to multiple possibilities of analysis and intervention. “Uncertainty is understood as ‘a challenge,’ as an adventure of urban development, as a space which cannot be determined and fixed but can be shaped through the projection of an activating image and can be brought into a specific ‘disposition’: this space cannot be ‘defined’ functionally, but one can at least give it a positive ‘mood’ in order to conceive it as an open space of possibilities” (p. 161). With this spectrum being so wide, it is difficult to delimit and present all the infinite workable programmes.

The city can only experiment on itself, so why not experiment with these indeterminate remnants to develop new strategies which allow diverse spontaneous appropriations? Their ultimate goal would be to become a public space filled with diversity, where ideas merge into a free arena of expression and interactions in the public stage.

Architecture must continue to look for even more inclusive approaches, interacting with the problems of the city and extending its ongoing dialogue with other disciplines, proposing strategies involving direct community participation to encourage significant change in the communities where these transformations might take place. Interventions in neglected neighbourhoods could redefine the existing limits of the urban dynamic to boost its potential towards the direct benefit of specific communities by considering their initiatives, erasing negative perception, and allowing undetermined planning. Multidisciplinary stakeholders, together with architects and artists, have the opportunity to propose attractive, dynamic, and functional solutions, to act as catalysts for change and public life.

Everything is a space___between. A state of suspension between A and B. It is like marking pages in a book with a sticky note, or highlighting some text, carefully selecting. We leave some untouched, and we wait for something to happen, perhaps fast or slow, maybe now or never.