Introduction

When I lived in Diego, I was like a tropicbird in the light. We lived freely, like birds without branches. -A song composed by Jessy Marcelin, documented by Laura Jeffery (2007).

Mick Smith (2011, p. xvi) asks in his Against Ecological Sovereignty: “Isn’t there now a real, and devastating ironic, possibility that the idea of an ecological crisis, so long and so vehemently denied by every state, will find itself recuperated, by the very powers implicated in bringing that crisis about, as the latest and most comprehensive justification for a political state of emergency (…)” This article answers affirmatively. With the case of the Chagos, it substantiates the spatial and epistemic violence of an abused notion of ecological crisis.

The Chagos Archipelago was sanitized in the 1970s for a US military base on its largest atoll, Diego Garcia, following a secret ‘exchange of notes’ that evaded legislative approval. The 1,500 Chagossian evictees were dumped in Mauritius and the Seychelles-made into a surplus population by the planetary-scale military-colonial network. Chagossians, now numbering 3,000 to 4,000, have become stateless and placeless. In April 2010, the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) declared ‘a marine reserve to be known as the Marine Protected Area (MPA)’ in the Chagos Archipelago, known as the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT), covering 544,000 sq. km-twice the size of the United Kingdom. Conservationists acclaimed that the decision to ban fishing created the world’s largest nature reserve in a region that is exceptionally rich in biodiversity (Nelson & Bradner, 2010). Of all the denounced forms of legal ammunition, the Chagos MPA, along with its fiction of terra nullius, inflicts the most significant violence by legitimizing environmental fortification based on a denial of the almost 200 years of Chagossians’ lived history. Although geographically remote, Chagos MPA is not a peripheralized natural exterior. It is deeply intertwined with the same socio-technical practices that produce the conflicts and inequalities in contemporary cities.

This article responds to three recent research concerns in ecological conservation and environmental justice: multiscale spatial analysis; epistemic system(s) of power; and an anthropological account of counter-hegemonic environmental narratives. Concerning research into environmental exploitation, there is a persisting gap between urban and rural areas, society and Nature. Despite Lefebvre’s (2003, p. 113) hypothesis of ‘the planetary nature of the urban phenomenon’ and Brenner and Schmid’s ‘planetary urbanization’ (2012), research on environmental exploitation rarely goes beyond the limits of traditional cities. Research across urban, infrastructural, regional, ecological-geographical and planetary-global scales is crucial to connecting the politics of exploitation and resistance in different contexts (Apostolopoulou & Cortes-Vazquez, 2019). Secondly, many would agree on interpreting socio-political processes through urban patterns (Myers, 2020). They have addressed non-local policies, institutional arrangements, global economic forces, and colonial and imperial legacies (Gezon & Paulson, 2004; Sachs, 1993a; Temper et al., 2015). Less attention is paid to the politics of environmental knowledge. It is imperative to create a bridge with ecocriticism and political ecology to reveal the epistemic root of environmental injustice (Fuentes-George, 2019; Latour, 2004; Marzec, 2015). Lastly, an analysis of the global system(s) of power should not dismiss local struggles, nor reduce localities to passive recipients and victims. There is a growing call for attention to be paid to the particular sensibility of local knowledge in deciphering our environment’s metaphysical, spiritual and sensational codes, and to their agency in empowering political resistance against dominant epistemology (Gezon & Paulson, 2004; Ingersoll, 2016).

To date, researchers have addressed the Chagos MPA from the perspectives of legal studies (Farran, 2021; Harris, 2014; Sand, 2009, 2014), social anthropology (Jeffery, 2007, 2014b; Jeffery & Rotter, 2019), political anthropology (Vine, 2009), environmental studies (De Santo et al., 2011) and environmental justice (Rambaree, 2020). Learning from this inspiring body of scholarship, I take a broadly-defined spatial approach to the Chagos MPA, which analyses how and why spaces are constructed, imagined, and experienced. The following analysis connects the Chagos case to environmentalism, anthropocentrism and political ecology. It probes historical and epistemic violence through spatial evidence.

This article starts by describing the Chagos MPA as fortress conservation. It traces a narrow definition of ecological conservation and its exclusionist nature to the concept of wilderness and frontier heroism. It argues that the violence of fortress conservation lies in the space of memory-it expunges the Chagossians’ lived history and represses their attempts to re-establish relationship to their homeland. Endeavours to better channel Chagossian voices and concerns via procedural and organizational improvements can hardly undo the terra nullius fiction that dismisses Chagossians as ‘unpeople’ and non-indigenous. The next section conducts a planetary-scale investigation. It reveals that the blue- and green-washing rhetoric invalidates Chagossian history while concealing unpoliced military activities and their environmental damage. This archipelagic network of extraterritorial powers demonstrates that Diego Garcia is not a ‘footprint of freedom’ but a landscape of exploitation. The following section discusses epistemic violence. It situates the Chagos MPA within the broader literature on environmental science’s colonial and imperial roots, emphasizing the (in)security rhetoric. It substantiates this claim by considering the Barton Point restoration project and highlighting the politics of the coconut. The last section briefly analyses Clement Siatous’ and Shenaz Patel’s works that imagine a collective homeland. Both view Chagos ecology as storied, layered and laminated through land-human interactions. They exemplify Chagossians’ techniques in creating a collective sense of belonging through spatial imagination.

Fortress conservation

On 1 April 2010, the United Kingdom established the Chagos MPA, including a no-take fishing zone, following limited discussion of the subject in bilateral talks with Mauritius. In 2011, Mauritius initiated arbitration proceedings against the United Kingdom, under Article 287 and Annex VII of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), challenging the designation of the Chagos MPA (In the Matter of the Chagos Marine Protected Area Arbitration (Mauritius v. United Kingdom), 2015). The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) acted as the registry in this arbitration, and the Tribunal ruled in favour of Mauritius (Mauritius v. UK, 2015, para. 547 (B)):

(1) that the United Kingdom’s undertaking to ensure that fishing rights in the Chagos Archipelago would remain available to Mauritius as far as practicable is legally binding insofar as it relates to the territorial sea;

(2) that the United Kingdom’s undertaking to return the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius when no longer needed for defense purposes is legally binding; and

(3) that the United Kingdom’s undertaking to preserve the benefit of any minerals or oil discovered in or near the Chagos Archipelago for Mauritius is legally binding.

The Tribunal declares, unanimously, that the United Kingdom breached its obligations under the UNCLOS’ Articles 2(3) on sovereignty; 56(2) on due regard to the rights of other states; and 194(4) on refraining from unjustifiable interference.1 The UK’s designation of the MPA without adequate consultation with Mauritius was deemed unlawful. The Tribunal found that the UK was under a binding obligation to return the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius when it was no longer required for defense purposes, and that consequently Mauritius had ‘an interest in significant decisions that bear upon the possible future uses of the Archipelago’ (Mauritius v. UK, 2015, para. 298). It is important to note that Chagossians were not heard in this arbitration. Their interests and demands did not align with that of Mauritius.

There have been encouraging but unsuccessful efforts to invite Chagossian participation. In preparation for a feasibility report on Chagossian resettlement later released in 2015, KPMG-the Anglo-Dutch accounting service provider-held consultation workshops with Chagossian communities in Crawley, London and Manchester in 2014. Issues include the insufficient notice given to study participants, delays in monthly updates, UK stakeholders’ influences over the study team, and misleading commitments to subsequent consultations (Jeffery & Rotter, 2014).

Legal complexities (and perplexities) are out of the scope of this article. The above suffices to demonstrate the power inequalities underlying Chagos MPA and how it fortifies against Chagossians and exclude their voices. Chagos MPA is reminiscent of the Mkomazi Game Reserve in Tanzania described by Dan Brockington (2002) as fortress conservation. This approach to conservation preserves wildlife and their habitat through the forceful exclusion of local people. The act of fortressing relies on the assumption that local people have harmed the environment, making it a ‘degraded Eden’, but Western science has the knowledge and the means to preserve it (Akyeampong, 2001; Grove & Anderson, 1988; Fairhead & Leach, 1996; Grove, 1995; Jacoby, 2014). It is of moral imperative to conserve the defenseless Nature-its wildlife, soil, water and forests-from the onslaught of humans, or more precisely, non-Western indigenes. Conservation is sanctified when eviction and exclusion are ignored.2

Chagos MPA takes on a narrow definition of conservation that finds its spatial archetypes in museums. Non-human natural elements are flattened and deadened into abstract and conveniently uncommunicative and inanimate objects. A curated list of species is conserved and represented as frozen images. Their inter-relationships and those with the Chagossian people are either dismissed or curated in an ahistorical manner. Here, curation serves to perpetuate epistemological superiority through the strategic acts of devaluing, discarding and enhancing. The curated Chagos has lost its complexity and diversity unless we recover intimate connections to land and unlearn the fantasized Nature. As William Adams (2004, p. 231) warns, ‘even if the diverse jewels of the earth are ‘saved,’ we will still face a gloomy trudge through the new century accompanied by the steady leaching of natural diversity on every hand’. Research activities can be equally ‘abusive’ when demarcating and romanticizing a no-take ‘nature’; scientists have to harvest and kill certain species to understand them. Healthy and harmonious reciprocity with Nature should not preclude utilitarian engagements of its people.3

The exclusionist nature of fortress conservation seems to be at odds with an underlying fascination with the frontier. In Uncommon Ground, William Cronon (1995, p. 79) writes:

“Seen as the frontier, it (wilderness) is a savage world at the dawn of civilization, whose transformation represents the very beginning of the national historical epic. Seen as the bold landscape of frontier heroism, it is the place of youth and childhood, into which men escape by abandoning their pasts and entering a world of freedom where the constraints of civilization fade into memory.”

Wilderness denotes more than terra nullius-land without value or property that is to be settled, civilized and improved by European farmers and their technologies. The wild Chagos is imagined as sublimely mysterious. It represents a new romantic frontier reminiscent of the nineteenth-century expansion into the American West. One of the former BIOT commissioners, Richard Edis, used precisely the ‘Wild West’ atmosphere to describe the heroic pioneer days of the new military society in the 1970s (Sand, 2009, p. 52). Thousand-plus coconut trees were removed for military construction. The over 10,000 Seabees serving on Diego Garcia and their diving contractors (Oceaneering International) had a reputation for unorthodox operational practices. For example, unstable surplus dynamite was occasionally detonated underwater to blow open ship channels or simply ‘in the reef for fun and profit’ with explosions that ‘rocked the island’ (Sand, 2009, p. 52).

What is pernicious about imagining Chagos MPA as virginal wild is that it fortifies the hierarchy between those who care and those to be cared for: on the one hand, the military as the defender of wildlife and scientists who possess and control specialized expertise and technologies; on the other, the displaced Chagossian people, who are seen as threatening the Chagos ecology. Remembering poet and environmentalist Judith Wright, Val Plumwood (1998) describes how the concept of wilderness is tinged by racism. She uses the removal of Tasmanians in 1833 to demonstrate that the environmental terra nullius assumes not simply a dualistic human-nature. It virulently asserts the intellectual agency, moral superiority and political dominance of modern culture and science over the aboriginal people-the not fully human inhabitants of Nature. This is precisely how Western historical accounts remember Chagossians: ‘unpeople’ and un-indigenous (Curtis, 2003, p. 421, 2004; Sand, 2009, p. 24). According to a diplomatic cable from the colonial office in London (1966), their historical presence is unfortunate and inconvenient.

“Unfortunately, along with the Birds go some few Tarzans or Men Fridays whose origins are obscure, and who are being hopefully wished on to Mauritius, etc. When this has been done I agree we must be very tough and a submission is being done accordingly.”

In an effort to escape the purview of the UN Committee of Twenty-Four, in 1966, the Colonial Office of the BIOT avoided the term ‘permanent inhabitants’ in relation to any of its islands and, instead, described Chagossians as ‘belongers’ of Mauritius or the Seychelles and only temporary residents in the BIOT (Sand, 2009, p. 17).4 It was later confirmed that the establishment of a marine park was deployed to create the fiction of ‘no human footprints’ and to ‘prevent any of the Chagos Islands’ former inhabitants or their descendants from resettling in the BIOT’ (Mills, 2010, par. 7, 15). In contrast to the terra nullius alibi of typical settler colonialism that essentializes the naturalism of indigenous cultures, Chagossians are not even part of the fauna and flora. In addition to their material loss of livelihoods and dwellings, Chagossians are removed from the history, memory and representation of Chagos. Except in an imaginative mode, they are deprived of control over the management and narration of their environment. Their erasure is complete and undisguised.

Archipelagic network and military exceptionalism

Geography is the new canvas. The Chagos fortress serves not simply Diego Garcia, but an underlying archipelagic network. Examining the Chagos MPA at various scales, especially the planetary one, is essential to grasping the full complexity of how power becomes codified and institutionalized. Although geographically remote, Chagos is deeply enmeshed in the same system of power that produces dynamics and politics in an urban context. It is the most innocuous agent of the system because it is painted ‘blue’. Diego Garcia is only one example of the unbounded military network of the United States, that, according to Vine (2020), now consists of over 800 bases outside the 50 states and Washington, DC.

Many have theorized on this mismatch between Chagos’s limited physical territory and its unbounded territoriality under Sassen’s (2008) framework-territory being a physical concept with defined and continuous spatial limits and territoriality being a legal construct dictated by powers and networks, forces and flows which disrupt geographical borders. Agamben’s state of emergency is widely cited to describe the Chagos as an exceptional space outside the normal rule of law, where the temporary suspension of the legal system acquires a permanent spatial location (Agamben, 2005; Clemens et al., 2003). Commenting on UN trust territories, tax havens and refugee camps, Franke and Weizman argue that the old political order has been shattered and shredded into a discontinuous territorial patchwork of introvert enclaves, fortified by invisible security apparati (Franke & Weizman, 2003). Building upon these works, I further argue that the Chagos evidences a construction of territoriality that is alarmingly novel in 3 ways: spatially, it belongs to an expanding system of remote and disconnected archipelagic nodes; in a temporal sense, it operates in a protective, pre-emptive and projective manner; thirdly, it relies on science-or more precisely, scientism-for its epistemological legitimacy instead of purely military or political might.

The archipelagic spatiality was first conceived around 1958 by Stuart Barber who suggested occupying strategically-located and lightly-populated islands to maintain the US Navy’s presence overseas (Vine, 2009). The twenty-first century notion of ‘lily pads’ complements this network by inserting small and covert security locations (Vine, 2015). After Ungers (2013), the archipelago is not a new metaphor, nor is it exclusive to the literature on militarism. Roberts and Stephens (2017) have edited a new book, Archipelagic American Studies, that seeks to theorize our highly-fluid world irreducible to an assemblage of sovereign states. To them, the notion of archipelago, both metaphoric and material, offers a new analytic to navigate the transnational, transatlantic, transpacific, trans-indigenous, and transhemispheric turns. They further argue the topographical coherence of island groups exist discursively as power-constituted, and only in relation to national, imperial, linguistic, ethnic and other heuristics, to which I would add the ecological one, which is particularly salient at the Chagos.

The Western arm of the atoll of Diego Garcia experiences extensive military construction, where Nature has no defense. Many environment-related treaties to which UK and Mauritius is a party are not applicable here, such as the 1972 UNESCO World Heritage Convention and the 1992 Rio Convention on Climate Change and Bio-Diversity (Sand, 2009). Other legal blackholes or environmental regulations that are delayed in their implementation include: the BIOT Fisheries (Conservation and Management) Ordinance (2007), the 1971 Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance (ratified by the UK in 1976), Natural Resources Conservation Land Management Plan drawn up in 1973, and US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations including US Navy’s Environmental and Natural Resources Program Manual (Dunne, 2018; Sand, 2009, 2021). This blue- and green-washing strategy common to military buildups inflicts a ‘double erasure’ of Chagossians’ lived history and the military’s tactical urbanization. The latter intensified in the mid-70s and early 80s following the increasing Soviet presence in the Indian Ocean and continued until now (De Santo, 2020; Disapprove Construction Projects on the Island of Diego Garcia Hearing, 1975).

Of particular significance is Diego Garcia’s capacity as a logistical base. By 1983, the Seabees, along with private contracting firms specializing in underwater explosives and harbour dredging, had blasted 4.5 million cubic meters of coral fill for infrastructural projects, including expansion of the runway, wharf, and piers, and for the accommodation and anchorage of a full carrier-force fleet in the lagoon (Bélanger & Arroyo, 2012, p. 62). As a result, Diego Garcia boasts the world’s longest slipform-paved airport runway built on crushed coral, which served as the principal launch pad for the bombing of Iraq and Afghanistan (Sand, 2012, p. 37). Its inner lagoon has been deeply dredged to accommodate aircraft carriers, nuclear submarines and a large fleet of forward supply vessels in service of the Maritime Pre-positioning Ship Squadron (COMPSRON), the Military Sealift Command Office (MSCO), the U.S. Fleet and Industrial Supply Center (FISC) among other tenant commands. This, as a British visitor described in 1983, staged “a panorama of the American war machine (…) that made Pearl Harbor look puny” (Sand, 2009, p. 37). Conservation studies that zoom into the corals and birds tend to forget this network-centric warfare playbook. To demonstrate the scale of the global logistical movement of the US military, Bélanger and Arroyo (2012, p. 57) write, “(n)either metric nor imperial but geographic, the amount of material moved by MSC accounts for itself in terms of continents and water bodies such that to transport its cargo, the MSC must quite literally move volumes on the scale of mountains and square footage on the scale of islands”.

Despite being a planetary landscape of exploitation, Diego Garcia is often referred to as the ‘Footprint of Freedom’-perhaps the most ironic note to Foucault’s reflection in the Birth of Biopolitics: “In short, strategies of security, which are, in a way, both liberalism’s other face and its very condition (…) The game of freedom and security is at the heart of this new governmental reason (…) The problems of what I shall call the economy of power peculiar to liberalism are internally sustained, as it were, by this interplay of freedom and security” (2008, p. 65). Indeed, the Chagos creates the problem of insecurity, to which itself is the solution. The solution comes before the problem.

Militarized environmental science

This imagining of the Chagos and its subsequent planetary-scale planning reflects the elevated vantage point of the military-environmentalist alliance. Sachs (1993b, pp. 17-18) compares it to how an astronaut views the globe: “(…) an object of science, planning and politics”, that is “(…) suspended in the dark universe, delicately furnished with clouds, oceans and continents”.

Scholars have traced the emergence of environmental science to colonialist governance of knowledge. Richard Grove (1992, 1995) relates the origins of modern environmental concerns to European expansion with particular focus on French Mauritius and the British Tobago and St. Vincent. Colonialist environmental science played an essential role in developing the climax of anxieties in the mid-nineteenth century about artificially-induced climate change, environmental degradation and loss of species. Anker (2001, pp. 1-2) also describes the governance agenda: “(t)he formative period of ecological reasoning coincides with the last years of the British Empire,” and that imperial agency saw the modern science of ecology as one of the “urgently needed tools for understanding human relations to nature and society in order to set administrative-economic policies for landscapes, population settlement and social control”. The essays in The Lie of the Land, edited by Leach and Mearns (1996), challenge false claims that indigenous practices bring about environmental degradation. They reveal how these ‘lies’ alienate the right over land and control over the environment from poor rural dwellers and transfer them to governments and international agencies. Some support a crisis narrative to justify external intervention (Roe, 1995), while others uphold an agenda of social control (D. Anderson, 1984; Beinart, 1984). As a result, environmental policies in the Global South tend to prescribe a solution prior to the enunciation of a problem-both constructed by the same colonial regimes. Many such policies raise alert over the loss of a premodern human harmony with Nature and warn of calamities that will plague people and Nature if dramatic action is not taken soon.

Bacon (2019) and Watts (2013) have discussed the epistemic violence of colonialist science. Whyte (2018) describes two patterns of environmental injustice-vicious sedimentation and insidious loops. As environmental changes compound over time, settler ignorance against indigenous people is reinforced while historical settler industries that violate indigenous people further environmental violence. Tuck and Yang (2012) are radical critics of settler colonialism’s profound epistemic, ontological, cosmological violence. Rejecting reconciliation as it is about rescuing settler normalcy, they advocate for an ethic of incommensurability that relinquishes settler futurity and abandons the hope that settlers may one day be commensurable to Native peoples. Mignolo and Walsh (2018, p. 144) most explicitly address epistemic violence. They state that patriarchy is located in the domains of enunciation and in the establishment of knowledge itself-a ‘field of representation’, a ‘set of rhetorical discourses’, a ‘set of global designs’. Decoloniality needs to focus on changing the terms of the conversation so as to change the content, not vice versa.

Val Plumwood and Donna Haraway broaden the critique on the colonizer-indigene division to that between Nature and culture, humans and non-humans. For Plumwood (2003), anthropocentrism5 parallels Eurocentrism. Both presume a hierarchy of cultures. Both justify the colonization of non-human Nature through the imposition of colonizers’ land-forms and visions of ideal landscapes. In Staying with the Trouble, Haraway (2016) suggests the failure of bounded individualism. She argues for sympoiesis and tentacular thinking-with other beings, humans and not, recursively, inventively, relentlessly-with joy and verve (Ch. 2, 4). Arturo Escobar’s (2020) ‘radical relationality’ and pluriversal ontologies echo both. His decolonial view of Nature and the environment involves “seeing the interrelatedness of ecological, economic, and cultural processes that come to produce what humans call nature” (2008, p. 155).

The military takes on a more significant role in administering environmental science. The institutionalization of ecology as an academic field is shown to be intertwined with US nuclear testing during the second half of the twentieth century (DeLoughrey, 2013). Leslie (1993) reveals that, in the quarter century after 1945, the interests of scientists and the military were often complementary. Bocking and Heidt (2019) focus on the military’s enthusiasm in the Arctic in the same period. All scientific works, strategic and non-strategic alike, were encouraged, from tracking whale and bird migrations to surveying polar bears and lemmings to ethnographic research with the Inuit. In the Arctic and Greenland, science became a kind of political performance-a means of asserting national authority over territory through studies of glaciers and the ionosphere. In 1983, the National Military Fish and Wildlife Association (NMFWA) was officially chartered, many of whose members are affiliated with the US state Department of Defense. James Bailey, an army wildlife biologist and a member of ‘new defenders of wildlife’, once declared, “if we weren’t here, this land would be all marinas and condominiums (“here” being the Aberdeen Proving Ground in coastal Maryland)” (Coates et al., 2011, p. 467; Cohn, 1996, p. 11).

The military-environmental-science entanglement acquires a new and aggressive momentum by exploiting the current climate crisis. The proclamation of the North-western Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument in 2006 triggered a ‘conservation race,’ or ‘environmental territorialization’ that sought to solidify jurisdictional claims in remote areas and to shield military installations from environmental scrutiny (De Santo, 2020; Rauzon, 2015; Rieser, 2012). This collision and symbiosis between conservation, militarization, geopolitics, tourism and commodification of Nature have been well investigated in different contexts: Guam (Bélanger & Arroyo, 2016), Okinawa and Bikini Atoll (Davis, 2015), Vieques (Arbona, 2005), Hawai’i and the Philippines (Gonzalez, 2013). The military performs as a restorer of Nature, a steward of a virginal wilderness, and a defender of freedom with the disciplined practice for future combat-a history of ‘hallucinatory multiplicities’ (Arbona, 2005, p. 37). It is hard to separate environmental conservation as ideologically external to the socio-political reality. The resulting hegemonic ideological gestalt reproduces and amplifies existing socio-political tensions, as seen in incidents of conflict associated with new MPAs (Canovas-Molina & García-Frapolli, 2020).

Ecological (in)security is a new rhetorical device. If the self-reinforcing legitimation of a conservation-capitalism marriage is the sustainable and rational use of Nature (O’Connor, 1993), then the conservation-militarism alliance can be said to share a similar objective: the securitized use of Nature. The overwhelming need for ecological security seems to justify any measures of the war machine. Admiral T. Joseph Lopez, former Commander-in-Chief, US Naval Forces Europe and of Allied Forces in Southern Europe, proclaims “(…) climate change will provide the conditions that will extend the war on terror” (The CNA Corporation, 2007, p. 17). Nature, now understood on a planetary scale, has allowed global powers to permeate into local politics and refashion local concerns as universal, consequently demanding global measures. In his Militarising the Environment, Marzec (2015) best defines this socio-political mission as environmentality.

Environmentality is, in part, the name for a militarized mentality, one that commandeers a consciousness to wholly rethink and replace a rich, complex, multinarrative environmental history with a single eco-security imaginary for the post-Cold War, post-9/11 occasion. It is a pattern of thought that seeks to justify increases in national and civilian security by generating increased amounts of insecurity (…) environmentality is essentially environmentalism turned into a policing action. It names a hyperbolic mode of intelligibility, where security and insecurity collapse into one another and become indistinguishable. (Marzec, 2015, p. 4)

For Marzec (2015), the end of tackling ecological disasters justifies any means deployed as self-evident, and embodying organic rationality. He problematizes this construction of environmental science. Given the unprecedented challenge of climate change, the military finds it imperative to take direct action to manage a fundamental ecological unpredictability generalized beyond any national or continental, geographic border (Marzec, 2015). The sense of an exceptional situation paints military actions as following an apolitical, ethical obligation; their associated knowledge and projects can hardly be challenged. As a result, the imperativeness of conservation projects employing such rhetoric works to enforce and support dominant interests. Dissent is silenced.

Barton Point restoration project

Chagos MPA has elicited wide attention from different scientific communities. A brief overview of the most recent scientific publications demonstrates the breadth of their investigations: coral reef (Carlton et al., 2021; Sheppard, 2013), cryptofaunal decapods (Head et al., 2018), sea turtles (Esteban et al., 2016), sharks and reef fish (Curnick et al., 2020; Samoilys et al., 2018), climate science and geological change (Pfeiffer et al., 2009; Sheppard et al., 2002). While the list is not exhaustive, it reveals a persisting tendency to see Chagos as a passive and feminized object for disinterested scientific inquiries. The Chagos Conservation Trust (CCT), a UK charity established in 1992, maintains a messianic mentality. Under the shield of science, the protection and conservation of Chagos carry an innate political legitimacy and moral superiority. Chagos MPA is often described as a ‘sanctuary’, a ‘refuge’, a ‘scientific reference site’, and a (safe) ‘haven for the Indian Ocean’s exploited wildlife’ (Chagos Conservation Trust, 2020, pp. 13, 7, 16, 18). Alistair Gammell, CCT Chair, argues for complete and total protection of the Chagos ocean under which “(…) what the eye doesn’t see, the heart doesn’t grieve” (Chagos Conservation Trust, 2020, pp. 4-5). Conservation has become an unchallenged ideology even though it securitizes Nature both against humans and for humans. In its most fantasized version, Nature is not only exploited for economic production, but also deployed for the ideological legitimation of the unnatural systems of the military.

Environmental science constructed around the Chagos and the burgeoning research activities is militarized for three interrelated reasons. First, the fortified Chagos hinders Chagossian engagement with Western environmental scientists in forming a conservation plan that is both ecologically and socio-culturally sustainable (Jeffery, 2014a, 2014b; Sand, 2012, 2014). While both parties have expressed a willingness to share knowledge and to set conservation priorities through a democratic procedure (Jeffery, 2011), the deep-rooted exclusionist tendency prohibits their meaningful collaboration. Second, it erases Chagossian history and memory through ecological restoration that views the Chagossian as harmful. As this section will demonstrate, the politics of the coconut is central to the stage of contestation. A knowledge-fear-security nexus sanctions Chagossian’ historical settlement, and demonizes the Chagossian-coconut relationship as one of exploitation rather than one of care. What is manufactured is a total anxiety about a permanent danger, against which permanent forces are necessary for total defense. Third, fear suffocates the imagination of the past. Historical data is dismissed or simplified in current scientific research based on speculative projections that the present landscape is degraded from before and that unpopulated wilderness is the norm (Leach & Mearns, 1996). It implies that Chagossian knowledge is traditional, un-experimental and emotional-subject to enlightenment by proper science.

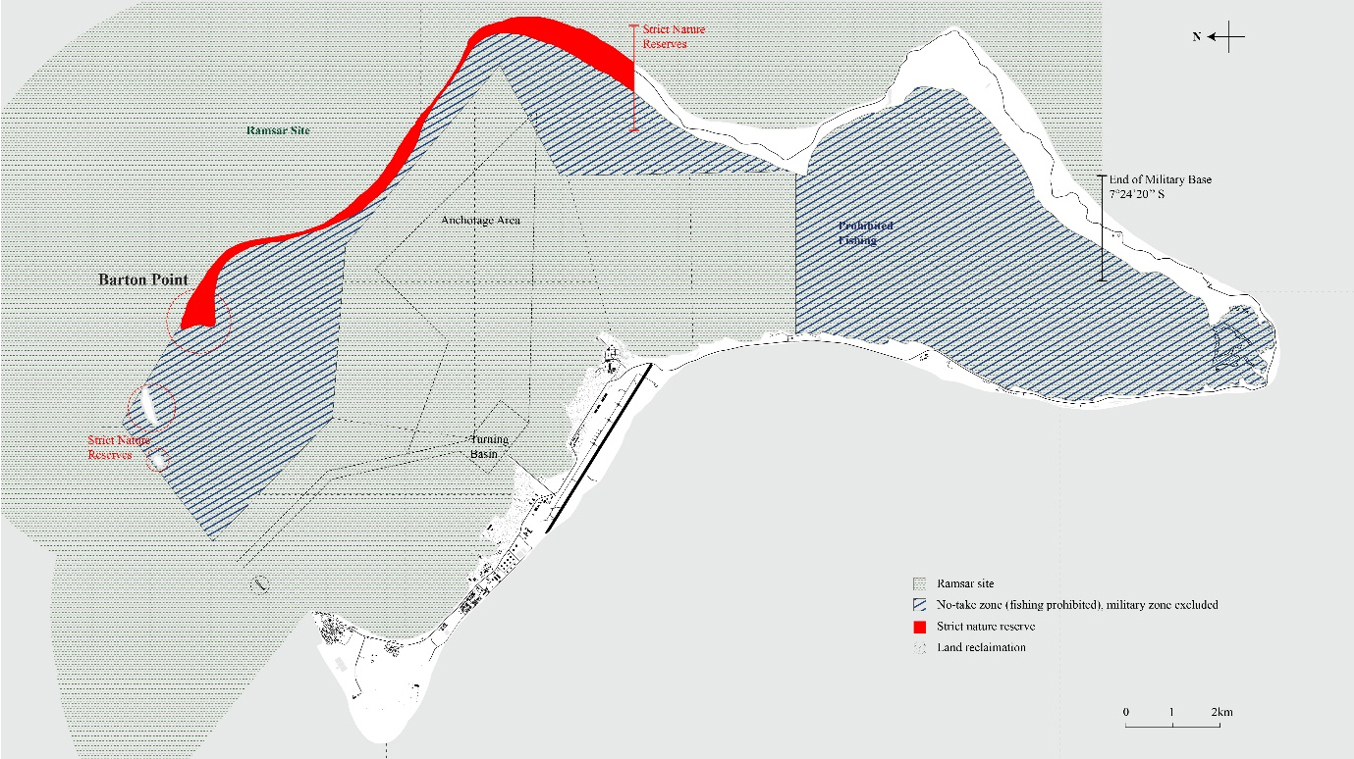

Barton Point sits at the tip of Diego Garcia’s Eastern non-military arm. It is fortified within a strict nature reserve, a Ramsar site, an Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA), and a no-fishing zone (Figure 1). If one looks carefully at Google satellite images, one can detect layers of habitation, use and rituals that traverse the dense field of vegetation (Figures 2 and 3). The nineteenth-century grids of coconut plantations stand out among the hardwood populations along with evidence of freshwater pools and crafted hillocks. Barton Point Hardwood Restoration Project is an ambitious pilot scheme initiated in 2009 to cut down coconut palms and replace them with ‘native’ Pisonia Grandis, Morinda citrifolia and Intsia Bijuga (Carr, 2010). Peter Carr, a British military officer on Diego Garcia, describes ‘suppressor’ coconut palms as if they should be removed in a similar manner as the Chagossians given their falsely perceived damage to the environment:

“(…) the reversion of the monoculture of coconut Cocos nucifera stands back into what stood before the days of the plantations. On all islands where coconut was cultivated as a crop, the relict stands have formed dense, overgrown areas that have become virtually uninhabitable for any other flora. As a result, these anthropogenic suppressors of biodiversity have earned their description of ‘coconut chaos’” (Carr, 2010, p. 16, author’s emphasis).

It is critical to unpack the politics of restoration. The idea that anthropogenic traces taint the landscape echoes the definition of ecological restoration formulated by the Society for Ecological Restoration (SER): “the process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed” (SER, 2004). With a mission to restore an original virginal condition and make restitution for a loss, the team at Barton Point forges continuity only with a selected past: the period before Chagossians were brought to the archipelago as enslaved plantation workers. Between Chagossians’ arrival to and their forced displacement from the Chagos, a 200-year history of transiency is annihilated. However, the landscape remembers. For example, Chagos vegetation dynamics-the shifting dominance of Pisonia grandis, Hernandia, Tournefortia and Cocos nucifera (Carr et al., 2013, p. 276)-corresponds to the change of human settlements at Barton Point: from the imprisonment of convicted lepers at East Island during the mid-nineteenth century (Anderson, 2000, p. 42), to the increase in both plantation production and the import of Chagossian labours in the late-nineteenth century, and lastly the displacement of them all in the 1970s (Evers & Kooy, 2011). At other areas of the Diego Garcia island, Bárrios and Wilkinson (2018) observe other introduced plant species potentially linked to a network of copra trade and slavery migration: casuarina equisetifolia L., native to Australia and to Asia; tabebuia heterophylla (DC.) Britton, native to the Caribbean; bryophyllum pinnatum (Lam.) Oken, native to Madagascar and Cook Islands; Rivina humilis L., native to tropical and subtropical America; and Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit, native to Central America and Mexico.

The above records invalidate the idealization of a pristine wilderness and reveal an opportunity to read Chagossians’ lived history through the ‘convicted’ introduced species. Their removal is not necessarily corrective or restorative. Rather, it is harmful as they are the only remaining physical evidence that Chagossians came and lived here. Restoration as such fabricates amnesia of the period during which Chagossians lived and laboured. I suggest reading this project as juxtaposing a contemporary layer to the existing palimpsest landscape, which is storied with human activities and geological history. It is a reconstruction, if not a recolonization, with approved, endemic plant species. As Drenthen (2009) suggests, in uncovering the deeper historical layers of a landscape, it is important not to destroy more recent depositions or to remove any prior meaningful interactions with the landscape. As place-visitors but not legitimate place-dwellers, the most researchers can do is to provide a credible narrative that makes the place and its historical layers legible instead of disciplining the landscape with a template of faked wild. Restoration weaves a new veil. It involves no less anthropogenic forces and is instead a painfully laborious process. Since 2009, the removal of coconut fields upon which Chagossian laboured for generations has been a violent and aggressive event in itself. People from both the military and civilian community on Diego Garcia work industriously to remove coconut saplings, nuts and leaves to clear sites where trained chainsaw operators have cut down large coconut palms. On top of logistical complications, a robust, well-disciplined, experienced and trained workforce is selected given the physical exertion necessary to work in rough seas with strong currents, coupled with inclement wet or hot weather (Carr, 2010, p. 15).

Source: Google Earth Satellite Image. Data Provider: Maxar Technologies. Last accessed: 7 April, 2021.

Figure 2. The gridded fields of coconut palms north to East Point, Diego Garcia (2016)

Source: Google Earth Satellite Image. Data Provider: Maxar Technologies. Last accessed: 7 April, 2021.

Figure 3 The gridded fields of coconut palms stand out from lower hardwood populations at Barton Point, Diego Garcia (2016)

Coconut palms are particularly important to Chagossians’ cultural landscape, and by extension, their destruction annihilates Chagossian cultural expression and represses social productions. Chagossians repeatedly emphasize that all parts of the coconut plant can be used. Nothing should be thrown away: ‘dried coconut flesh (copra) was pressed to produce coconut oil, and the remaining fibrous copra meal could be used as animal feed; coconut shells could be heated and used for ironing; coconut husks were burned as a cooking fuel, and the ashes could be mixed with coconut oil to produce soap; coir from the husks was made into mattresses and pillows; and coconut fronds were used for roofing, woven into brooms, bags, and baskets, or twisted into ropes’ (Jeffery, 2014b, p. 1004). The issue with the Barton Point restoration project lies not in the fact that it cuts down coconut palms but that its underlying corrective and restorative mentality ignores Chagossians’ modes of caring. On top of their intrinsic values, coconut’s socio-cultural significance is enacted through acts of cutting and clearing that commemorate the human past and simultaneously inscribe a human future on Chagos (Johannessen, 2011). Processes matter to demonstrate that Chagos needs its former inhabitants to keep its environment tidy and usable. Chagossians did cut down coconut trees. Some even volunteered to join the controversial restoration project, including Allen Vincatassin, President of the Diego Garcia and Chagos Islands Council in the UK but for different reasons. In line with the traditional practice of labati (weeding) and netwayz (cleaning, tidying, weeding), Vincatassin describes that clearing some coconut palms will make the area ‘more alive: we will be able to see the old houses which we can’t see now because of the forest, and in three years people will say ‘that’s the plantation I knew’’ (Jeffery, 2014b, pp. 1004-1005). Chagos is not a world already constituted with aesthetic objects of detached research concerns and interests. Chagossians dwelt in it. Chagossians continue to be part of it in an imaginative mode.

I challenge Charles Sheppard’s (2014, p. 85) claim that the Chagos MPA “does not infer any value judgement on the rights of the people involved”. The idea that protection of the Chagos is unrelated to the Chagossians is itself a value judgement because it denies Chagossian cultural-historical attachment to their land. I have no intention to discredit the restoration project in removing harmful dominant species that threaten biodiversity. I hope to emphasize that any engagement with coconut-planting, cultivating and uprooting-has its socio-cultural drivers and implications. Both the pre-1970s and contemporary periods of Chagos’ history are human history. Pierre Bélanger (2009) demonstrates that ecologies are constructed-the complex biophysical system preconditions modes of production that are inextricably bound to urban systems. In the case of Barton Point, I argue that ecologies are also narrated, storied, fictionalized, imagined, rhetoricated. They precondition not just economic production but the production of scientific knowledge. Our knowledge of Chagos ecology would remain deficient at the epistemic level if layers of Chagossian participation continue to be dismissed and repressed.

What is alternative restoration? I value approaches that consider traditional ecological knowledge(s)-easily dismissed as ‘non-scientific’-for its cultural and historical concerns. Restoration is not simply about reducing anthropogenic forces but about whose agency restorative actions belong. There are established empirical facts that empowering indigenous agency can strengthen the effective management of the local environment (Fuentes-George, 2019). To make sound decisions about how we live and impact the non-human world, we should ensure that restoration engages an environmental culture that fully recognizes our dependency on the non-human sphere-both materially and in terms of attitude and ideology (Plumwood, 2002). Plumwood’s philosophy aligns with Chagossian practices in many ways. Both reject the privileging of the conceptual and scientific processes over material production driven by culture and ethics. Both agree that cultural and scientific goals are not irreconcilable. Rather, effective governance that synthesizes local culture with technocratic cause-and-effect would bring new lessons to both parties. This is where architecture, urban and landscape discourses are particularly appropriate at intervening. Instead of anxiously producing more knowledge, they can reclaim humans’ socio-historical relationships with the land. They can re-establish individual connections to Nature and natural processes by recognizing forgotten and dismissed Chagossian voices in the formation of a shared future.

Imagined homeland: a sense of belonging

The visceral experience and memory of displacement have compounded the vitality of Chagossians’ affective attachment to their homeland. Their various techniques of sustaining ties, including art, dancing (sega tambour), culinary and medicinal knowledge, are well-documented (Jeffery, 2007; Jeffery & Rotter, 2019; Jones et al., 2014). What receives less attention is the role of the environment in Chagossian imagination and memory in relation to their activism. I offer a brief analysis of their artistic practices that intimate human history as being implicated in natural history.

Drawings and paintings reproduce spatial memories. They are consciously deployed to imagine a collective homeland and to garnish support and unity for Chagossian social movements. While himself remaining on the periphery of the Chagossian socio-political organizations, the artworks of Clement Siatous have often taken centre stage in the Chagossian political and legal struggle for compensation and the right to return to Chagos. Siatous was born in 1947 to Chagossian parents living on Île du Coin in the Peros Banhos atoll. Like other Chagossian families, the Siatous family struggled with life in Mauritius. After arriving in Mauritius, Clement systematically recorded his memories of the Chagos Archipelago, motivated by his resentment against the authorities responsible for his marginalized condition in exile. “I started portraying my memories from Chagos because the British government said that there never existed any population in Chagos” (Jeffery & Johannessen, 2011, pp. 73-74). Having never been taught to paint-"I didn’t learn it in school; I simply can paint”-he interpreted his artistic skills as a gift from God, a sign of his mission “to tell the story of Chagos” (Jeffery & Johannessen, 2011, pp. 73-74). Siatous’ works are not fantasias but careful, exacting incarnations of individual memories and those of his community. The coconut is a recurring element: Siatous paints Chagossians cracking coconuts, grating the flesh, pressing and squeezing it for coconut milk; muscular woman carrying a basket of coconuts on her head; the working scene at the copra factory; men harvesting coconuts along with a grinning woman wielding a scythe.

Siatous uses bright colours to represent the mood and essence of the islands and layers it with details to conjure the bustling life on the islands (interview with De Gersigny, 2015). However, it is important not to romanticize the Chagos as it remained largely a colonized copra plantation. As of now, while even most built structures-mainly at the East Point on the Eastern arm of Diego Garcia-have become degraded after the Chagossians left, the administrator’ house and the church have been preserved, prizing a colonial vista over Chagossians’ perspective. The French-Creole style colonial house used by the plantation administrator, with its attic and green shutters, stands out among the tiny scrap-metal huts scattered throughout the cleared flat plantation landscape. A French naval officer, St. Cricq, described Diego Garcia as ‘a place of pain’ during his visit in 1811 (Carter, 2017). Enslaved workers were woken by the crack of a whip early in the morning. They brought ripe coconuts to the headquarter toward midday, and painfully pressed dried coconut flesh for oil using a specially-designed mill.

Another device to imagine Chagos is the boat Nordvaer, deployed in Siatous’ paintings for a sense of displacement and by Shenaz Patel for a metaphorical purpose. Mauritius-based author-journalist Shenaz Patel’s Silence of the Chagos (2019) draws from the testimonies of Charlesia, Raymonde and Désiré, three Chagossian refugees displaced to Mauritius. Patel paints a simple life on the Chagos-a life with the sea, copra production, poisson-banane recipes and the séga of Saturday night. This contradicts with their current exile in Mauritius. She uses Nordvaer to recount the circumstances of expulsion, the terrible hardships they continue to suffer, and their abiding yearning to return home. For Désiré, Nordvaer is his other name. At the age of twenty, he learns from his mother that he was born on the Nordvaer (Patel, 2019, location 760).

“Born? I was born on a boat? Where was it? Here? On the beach? How? Didn’t we have a house?” He watched his mother’s back as she sighed. “At sea. You were born on a boat at sea. The open sea. And no, we didn’t have a house anymore. Or a land. Or anything.”

Bragard (2008), in her analysis of Silence of the Chagos, invites attention to how dominant powers have increasingly taken control of waters and islands. She argues that Patel associates Nordvaer with the escalating US imperialism-its archipelagic global spatiality. Bragard sees the Nordvaer as the last connection to a possible homeland turned into a symbol of absence and rootlessness: “Yet the Chagossian identity remains difficult to locate: it is not in the Chagos, (…) nor in the sea (…) It is to be found in the dreams and hopes of an imaginary community that is struggling to reconnect with the physicality of its homeland which has, in turn, been turned into a non-place deprived of any sense of belonging” (2008, p. 144). Countering Bragard, Waters (2018) claims that memories of the ‘non-place’ of their closed islands continue to structure the exiled community’s intense and enduring sense of belonging in multiple physical, emotional and politico-legal senses. Despite their different emotive connotations, both are revealing accounts of how Chagossians are telling their stories with boat Nordvaer to express their complex, or even contradictory, feelings toward the past and the future.

Chagossians’ spatial imagination successfully nourishes a sense of belonging among their youngest generations who never had a chance to visit the archipelago. Piecing together stories from the elders, Chagossian children continuously (re-)imagine and (re-)invent a shared idyllic past and their kin. Evers’s (2011) documentation of Chagossian children’s drawings is a good example. Most of them compose the houses, albeit their different forms, at the centre with many family members living together in and around them. In some drawings, the deceased members and others of the larger Chagossian community are also mentioned:

“I have drawn my grandmother, my grandfather and mother. The house has a bathroom, and flowers, the sun is there and some clouds, there is a coconut pie and a vegetable garden (…) Chagos is the place of my grandmother. She is dead now. I want to go to Chagos to see the house of my grandmother” (9-year-old Lianne describes her drawing, in Evers, 2011, p. 259).

Wendel (2015, p. 4) defines an imaginative, spatial epistemology as one that “conjures alternative or future conditions (a utopia, penal colony, or just city) to conceive and realize political ideas”. In opposition to the preservationist, museum-based trope, the Chagossian imagination orients towards both the past and the future. They may not have read LeGoff (1992, p. 54), but they have demonstrated in action that, “(t)o make themselves the master of memory and forgetfulness is one of the great preoccupations of the classes, groups, and individuals who have dominated and continue to dominate historical societies”. The difference is that their weaving of collective memory serves not to dominate but to reclaim and empower. Their narratives work both projectively-by anticipating and planning for resettlement-and retroactively or nostalgically-by remembering Chagossians’ lived history along with their social practices and cultural traditions. Coconut and boat Nordvaer perform as critical subjects that are part of the larger cultural landscape. They ground the Chagossians’ imagination and nostalgia in a spatial experience. Suppose the construction of forgetfulness is the weapon of the dominant. Then the deployment of collective nostalgia is an equally, if not more, powerful and compassionate instrument of the dispossessed Chagossians to reassert their rightful claims to their land and history.

Conclusion

Building on the rich literature on terrestrial fortress conservation, I invite attention to the less-discussed marine parks that mediate international politics and construct planetary-scale networks of power. Chagos MPA reflects our fascination with wilderness and frontier heroism that are politicized by the same dynamics that shape our relationships to, and understandings of, cities. It is not an exceptional case nor a remote issue. Its narrative, imagination, fantasy, science and ideology follow the ecological discourse produced by and for the urban. In its most explicit manifestation, Chagos MPA protects and disguises Diego Garcia-a logistical hinterland that provides security to our homeland. Having revealed its spatial violence, I have also argued that the Chagos exposes not a deficit of knowledge but an epistemological deficiency. Science, in a militarized form, does not save Chagos but silences Chagossian people. The rhetoric of ecological (in)security further complicates the picture. Coconut is at the centre of this contestation. It is deployed both by the military-scientist alliance to demonize Chagossians’ lived history, and by Chagossians to fight back. Instead of militant confrontation, Chagossian strategies are subtler but more potent-their nostalgic uses of plant-centred spatial imagination better foster a collective sense of belonging.

My interpretation of Chagossian accounts of the environment as they affect the senses is only a small step toward a decolonized demilitarized future. I reject an anthropocentric construction of land as an inanimate backdrop for exploitative activities. I value an alternative reading of the Chagos ecology as storied through land-human interactions-cultivation, care, maintenance and stewardship. This is a respectful, reciprocal subject-subject relationship. The key distinction between militarized and demilitarized environmental science is that scientists do not learn about the land; they learn from the land (Wildcat et al., 2014). Scientists do not accrue scientific or anthropological facts about the Chagos. A more rewarding exercise would be to restrain the zeal for new discoveries and to humbly learn from spiritual, social and cultural connections to land. In subverting the objectified notion of landscape developed in the context of fortress conservation, a demilitarized environmental science shifts towards the lived experiences of people. Opportunities abound to merge Chagossian and Western epistemologies in a nuanced way to enrich our own disciplines. I envision both Western scientists and Chagossians engaging physically and intellectually in the deep-time spatial formation of the Chagos ecology. Both can benefit substantively. If we are serious about epistemic diversity, we must overcome the anxiety to produce new knowledge and listen carefully to the forgotten and dismissed voices of the Chagossians, among other impoverished, displaced, but persistently creative people.