Introduction: space, place, and place attachment

The main objective of this article is to understand the relationship that the residents of Fuzeta, a fishing village in southern Portugal, establish with the Ria Formosa Natural Park through the concept of place attachment. Recent studies on the relationship between individuals and places highlight the importance of this concept, but despite its abundant use, it remains in a stage of theoretical underdevelopment. Furthermore, the lack of research on the attachment to Portuguese Natural Parks endowed this research with an exploratory character and led to the need for a new definition of the concept of place attachment and to the construction of a new (and broader) analytical model.

To speak about place attachment normally implies establishing a distinction between the concepts of ‘space’ and ‘place’. Space is a part of the natural world with abstract characteristics not culturally interpreted (Gieryn, 2000). It becomes a ‘place’ when human beings interact with each other and attribute meanings and values to it, or to some of its characteristics (Gieryn, 2000). There are no meanings or values in the natural world, but during their social interactions and cultural practices, human beings attribute meanings and values to the spaces with which they relate. In turn, these aspects later define the meanings of these natural environments for the individuals (Greider and Garkovich, 1994). In this sense, Milligan (1998) centred his definition of place on the meanings that individuals attribute to it in the course of their social interactions. This author considers that places are socially constructed through the social interactions that take place in them. A place is, therefore, space that is symbolically marked (Milligan, 1998).

Thus, to understand the relationships that the individuals maintain with natural places, it is necessary to analyse the aspects that transform space into a place and, subsequently, the individuals’ attachment to places. Most of the studies on the relationship between individuals and places highlight the concept of place attachment. A bibliographic review carried out by Lewicka (2011a) between 1970 and 2010 identified approximately 400 publications on the subject of place attachment in more than 120 different journals within the scope of various disciplines. It concluded that the publications related to the connection of people to places had significantly increased. The most studied are places of residence (Lewicka, 2011a). However, there is a substantial number of other studied places, namely tourist locations (Correia, Oliveira and Pereira, 2014), commercial establishments (Felippe and Kuhnen, 2012), sacred sites, workplaces, sports venues, virtual or imaginary places (Lewicka, 2011a), natural places (Eisenhauer et al., 2000; Moulay et al., 2018), wild sites at risk and places of natural disasters (Manzo and Devine-Wright, 2014), natural places where recreational activities take place (Bricker and Kerstetter, 2002; Gunderson and Watson, 2007; Hufford, 1992; Reineman and Ardoin, 2018; Stedman et al., 2014; Tsaur et al., 2014; Wilkins and Urioste-Stone, 2018), landscapes (Riley, 1992), maritime environments (Wynveen et al., 2012), and public spaces (Mantey, 2015).

Within the several academic approaches to place attachment, the book edited in 1992 by the psychologist Irwin Altman and the anthropologist Setha Low, entitled Place Attachment, stands out (Low and Altman, 1992). This work emphasized the importance of the concept and offered a theoretical framework that guided many subsequent investigations. For its authors, the concept of place attachment can be defined as an affective or cognitive attachment of the individuals to the environment surrounding them. In this context, affective attachment means a special emotional relationship. Other authors also highlight the emotional component. Rubinstein and Parmelee (1992) defined place attachment as a set of feelings related to a given geographical location. There is an emotional connection when significant experiences occur in that place. Lewicka (2014) highlighted the fact that place attachment implies the fixation of emotions to a place, feelings of belonging, and the desire to stay close and return after leaving. Authors like Wynveen et al. (2012), Gustafson (2014), Stedman et al. (2014), Williams (2014) and Wilkins and Urioste-Stone (2018) also proposed that the meanings attributed to places could be a source of attachment. For Gustafson (2014), places can be meaningful to people for different reasons, giving rise to different types of attachment. For Stedman et al. (2014), and regardless of emotional or affective connections, meanings precede the attachments because people connect to places through the symbols they attribute to them. These meanings can be shared with the group (Eisenhauer et al., 2000; Wynveen et al., 2012), but some result from strictly individual experiences and are not shared with anybody else (Milligan, 1998).

One of the most mentioned aspects of place attachment is the relationship between the length of time the individuals remain in a place and their attachment to it (Gieryn, 2000, Lewicka, 2011a, Wilkins and Urioste-Stone, 2018). According to Lewicka (2011a, 2014), the length of the stay in a place is one of the most consistent predictors of place attachment. Although the residence in a particular place is also a predictor of attachment, this is particularly visible in the sentiments of sadness felt by people when leaving a former place of residence. As the author wrote,

“Places in which people reside for many years acquire meanings associated with several life stages, such as growing up, dating partners, marrying, having children, and getting old, which results in a rich network of place-related meanings, and offers a deep sense of self-continuity, something that more mobile people do not experience.” (2011a, p. 224)

The longer people live in a place, the more rooted they feel, and the greater their connection to that place. On the one hand, the attachments are related to childhood and adolescent experiences, and are most significant when these phases of life occur in the same place. On the other, they are much stronger than those that happen in more advanced stages of life (Silva, 2015). Degnen (2016) also emphasizes the role of memory in the attachment to a place, stating that memories create and maintain a sense of continuity, belonging, and identity. Memories were later adopted by several authors as indicators of place attachment to leisure places, such as Eisenhauer et al. (2000) and Gunderson and Watson (2007). The duration of the connections is also highlighted by Giuliani (2003). She argues that what defines the attachment to a place is a relatively long-lasting bond, with specific targets that other places cannot replace. The attachment to a place includes its physical characteristics, as well as the particular needs of the individuals, and their evaluation of that place compared to other places.

According to Brown and Perkins (1992), most authors have only analyzed the positive emotional and cognitive links to places. Nevertheless, they and some others, such as Carrus et al. (2014), Devine-Wright (2014), and Reineman and Ardoin (2018), have also included the negative emotions and sensations in their analysis. In this sense, they argue that place attachment

“(…) involves positively experienced bonds, sometimes occurring without awareness, that are developed over time from the behavioral, affective, and cognitive ties between individuals and/or groups and their sociophysical environment. These bonds provide a framework for both individual and communal aspects of identity and have both stabilizing and dynamic features. The environments may include homes or communities, places that are important and directly experienced but which may not have easily specified boundaries. Predominately negative connections to place characterize failed attachments, which may be experienced as alienation. Transformations in place attachment occur whenever the people, places, or psychological processes change over time. Disruptions of place attachment are noticeable transformations in place attachment due to noticeable changes in the people, processes, or places.” (Brown and Perkins, 1992, p. 284)

This approach covers both the various types of places and the positive and negative aspects of attachment. To operationalize the negative aspects of the connection to a place, the authors coined the concept of ‘disruption’. Disruptions imply the loss of attachment to a place due to natural disasters (like earthquakes, volcanic eruptions etc.), human-induced degradation (like pollution, overexploitation of resources, habitat destruction, etc.), voluntary and involuntary changes of residence, violence, wars, robberies, and so on, and can be sudden or intensified over time.

According to Devine-Wright (2014), most theorizations about place attachment do not contemplate the dynamism involved in the process, namely the great mobility of individuals in contemporary societies, and the transformation of places through ecological disasters, urban growth, or increased human pressure.

The approaches that encompass the dynamics of place attachment can be divided between those that focus on the transformations of the places that result from human induced changes, social transformations or natural disasters (Reineman and Ardoin, 2018; Wilkins and Urioste-Stone, 2018) and those that focus on the transformations that occur in people’s lives, such as those related to mobility or to the stages of life (Degen, 2016; Devine-Wright, 2014).

The impacts of the disruptions on the attachment to a particular place may vary in their nature, for instance becoming greater when the disruptions are extensive or sudden (Reineman and Ardoin, 2018) and according to the level of people’s attachment to the place in question (Devine-Wright, 2014). These disruptions may have devastating effects on people, specifically on their collective identity, memory, history, and psychological well-being (Gieryn, 2000). For Milligan (1998), when there is a break in the attachment to a place, individuals lose their connections with the significant experiences that occurred in their past and with those they hope will be significant in the future. However, disruptions on place attachment can also imply new attachments to new places, such as to a new home, a new neighbourhood, or a new community (Gieryn, 2000).

The emotional aspects have been one of the most studied issues in the analysis of place attachment (Low and Altman, 1992), but some authors have also highlighted the physical characteristics of the places (Gieryn, 2000; Stedman, 2003; Wynveen et al., 2012). Others have combined the natural aspects of the places with their social characteristics (Scannell and Gifford, 2010).

Milligan (1998) operationalized the concept of place attachment through two dimensions: (i) memories of past interactions with the place (interactional past), in which the more significant these interactions or their perceptions are, the greater the attachment to the place; and (ii) experiences perceived as possible or likely (or expected) to occur in the place (potential interactional), as the characteristics of the place also influence the activities that may occur in it, forming a series of expectations about future interactions in that place. According to this author, the formation of attachment to a place begins when people start to establish emotional connections to it, acquiring, at the same time, the perception that other places cannot replace it. Thus, the greater the place attachment, the greater the perception that the place is irreplaceable.

Research on place attachment is multifaceted, multidisciplinary, multidimensional, and multiparadigmatic (Moulay et al., 2018), but it remains in a stage of conceptual and theoretical development (Manzo and Devine-Wright, 2014). According to Lewicka (2011a), and Manzo and Devine-Wright (2014), there is still no solid theoretical body to support the great empirical use that has been given to the concept. Most of the theoretical approaches carried out in various disciplines still do not value some of the crucial aspects of the relationship between people and places. According to Hernández et al. (2014), there are as many operationalization forms of the concept of place attachment as the combinations of dimensions that have been addressed. Therefore, there is still a wide debate about the central dimensions of the attachment to a place and its relations with other concepts. Lewicka (2011a) argues that studies on the relationships between people and places seem to be stuck for conceptual reasons, and by the attempts to fit different concepts that are treated as pieces of a puzzle that should already have been completed. For this author, the progress that has been made is mainly due to the development of several measurement scales and to the use of the concept in contexts other than that of the residential or the neighborhood. But apparently these signs of progress have not been sufficient for actual theoretical development, as the references to classical works continue to be used in the very same way they were several decades ago (Lewicka, 2011a).

Back in 1992, Low and Altman argued that due to the diversity of the conceptual approaches, place attachment could be not just a phenomenon, but a variety of phenomena, as the same concept implies: (i) various types of attachment to a place that involves the interaction between affections and emotions, knowledge and beliefs, behaviours and actions; (ii) various types of places, which vary in scale, specificity, and tangibility; (iii) various types of actors and different social relationships, which may include the attachment of a single individual, a family, the circle of friends, the community or the cultural group; and (iv) linear and cyclical temporal aspects (Low and Altman, 1992).

The study carried out in Poland by Lewicka (2011b) stands out in addressing this problem because it allowed the identification of five different types of orientations of the individuals towards their places of residence. There are two types of attachment: (i) a ‘traditional’ or unconscious one, which refers to continuity and to the place as ‘roots’ and (ii) an active ideological and reflected one. And there are three types of non-attachment: (i) ‘alienation,’ which implies explicit negative attitudes and withdrawal, (ii) ‘relativity’, which means ambivalence and acceptance, and (iii) ‘placelessness’, which refers to an attitude of indifference towards the place.

Proposal for a new analytical model of ‘place attachment’

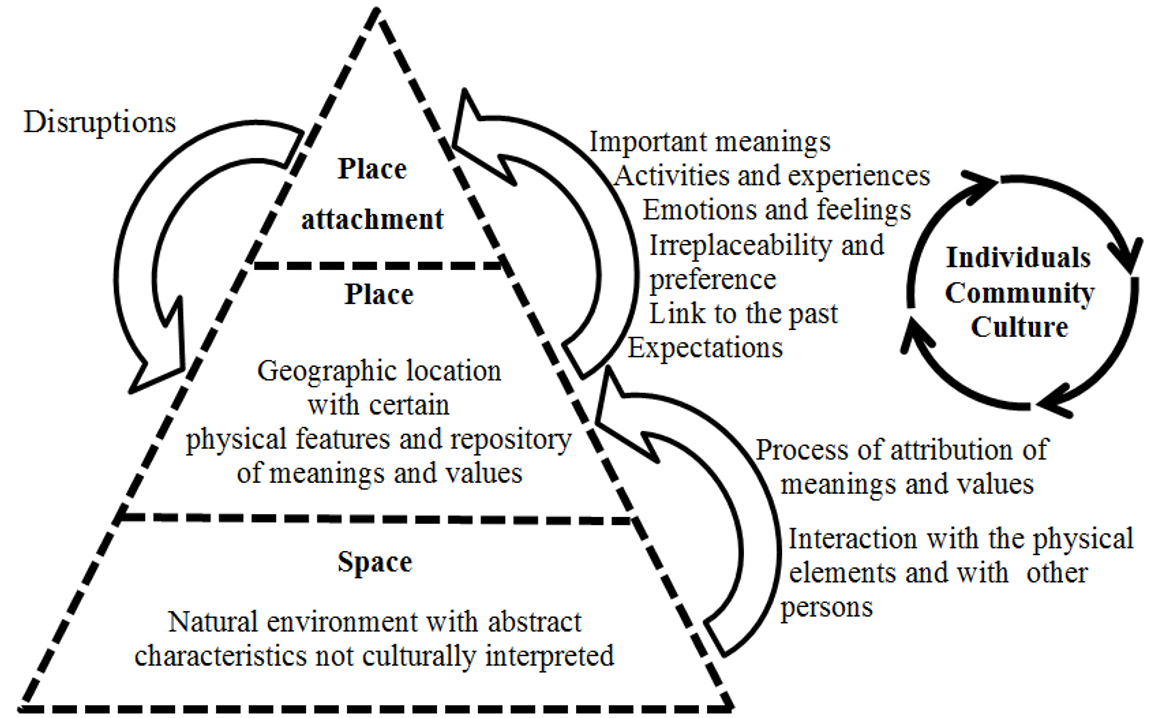

The attribution and maintenance of meanings and values to the places implies not only the relationship of people with the physical elements but also the interaction of individuals with each other (Degnen, 2016; Milligan, 1998; Williams, 2014; Wynveen et al., 2012), their sharing of history and culture (Low and Altman, 1992; Eisenhauer et al., 2000; Gieryn, 2000; Hufford, 1992; Wilkins and Urioste-Stone, 2018), and other aspects that can either strengthen or weaken people’s attachments (Brown and Perkins, 1992; Devine-Wright, 2014; Low and Altman, 1992; Reineman and Ardoin, 2018; Stedman, 2003). Taking this into account, we propose in this article a new analytical model (Figure 1) that includes, at the same time, the factors that participate in the transformation of spaces into places, and also those that participate in the place attachment process whether in a contributory way or in a disruptive way.

According to the literature, the formation of place attachment involves emotions and feelings linked to the meanings and values that people attribute to a particular place and the perception that it can barely (or cannot) be replaced. This process depends on the physical, social, and cultural characteristics of the place, but also on the activities and experiences that take place in it.

Disruptions in the attachment to a place can be related to significant transformations that occur in the physical, social, or cultural elements of the places (for instance, natural disasters or man-induced degradation of the ecosystems) or to transformations that occur in the individuals lives that contribute to a decrease, or even to a break, in the place attachment (accidents, death of relatives, etc.). Thus, a broad view of place attachment must include both factors that contribute to the attachment and factors that decrease or break the attachments (the disruptive elements), as they correspond to both sides of the same coin.

Besides the oscillations of the attachment due to the disruptive factors, (see Lewicka, 2011a; Low and Altman, 1992; Devine-Wright, 2014), the proposed conceptual model also contemplates the dimension of the past, through the memories of previous experiences (Degnen, 2016; Milligan, 1998; Riley, 1992; Silva, 2015), and the future, through the expectations about future interactions in and with the place (Milligan, 1998).

Based on contributions from several authors, the proposed model (Figure 1) expands the various conceptual approaches found in the literature and responds, at least partially, to the lack of a strong theoretical body of the concept of place attachment, an aspect highlighted by authors such as Lewicka (2011a) or Manzo and Devine-Wright (2014).

To support this analytical model, it is proposed that the definition of the concept of place attachment should include the meanings that are attributed to the place, the affective aspects and the perceptions of the place’s irreplaceability that result from people’s interactions with the physical, social, and cultural elements of the place, and the dynamics of the attachments, including the factors that can break them. In this sense, the following definition of place attachment is suggested: place attachment refers to individuals’ attachments to places resulting from processes of the attribution of important meanings and values, and the constitution of affective connections when practicing activities and other experiences that happen, that have already happened, or that individuals expect to happen. The attachment to a place is dynamic, and it implies aspects that can increase, weaken, or be broken.

Methodology of the study

To understand the relationships that the residents of Fuzeta establish with the Ria Formosa lagoon and also to validate the analytical model previously proposed, this empirical study adopted a qualitative interpretative methodology through the use of semi-structured in-depth interviews. Thus, during March and April 2019, 26 Fuzeta residents engaged in leisure or professional activities in the Ria Formosa lagoon were interviewed. These face-to-face interviews were conducted in Portuguese and taped; their average duration was one hour and a half.

The sampling method was the non-probabilistic snowball technique. However, to ensure the greatest possible diversity with the available resources, the interviewees were workers from several professional activities that use the lagoon - such as fishermen and shellfish catchers, as well as restaurant, hospitality, and transportation workers. However, the participants were also those engaged in leisure activities such as sunbathing on the beach, recreational fishing, the catching of shellfish and crustaceans, hiking, boating, windsurfing and camping in the lagoon barrier islands. The study also tried to include individuals belonging to institutions, such as the parish council (União de Freguesias de Moncarapacho e Fuzeta), and members of associations that pursue activities in the Ria Formosa Natural Park, namely the Clube Náutico da Fuzeta and the Associação Foz do Eta.

The interview script included four blocks of questions: a first one relating to the connections that the interviewees have, in the present, with the Ria Formosa Lagoon, a second one relating to the relationships that were established in the past, a third block relating to the perception of how these connections will be in the future and a fourth part dedicated to their socio-professional characterization. In each of the first three parts, an attempt was made to investigate the activities, experiences or interactions developed in the lagoon; the physical, social, and cultural elements involved in the connections between them and the lagoon, the importance of the place for them, and the disruptive factors in their relationship with the place. The third part also included two questions about the interviewees’ position regarding a possible move to a residence far from the Ria Formosa. The interviews were transcribed and the collected data were subsequently treated using the technique of categorical and thematic content analysis in order to ensure systematic, methodical treatment, and to minimize cognitive and cultural biases.

The methodological approach of the study of place attachment of the inhabitants of Fuzeta was conditioned by three main factors: (i) places are in constant flux and mutation, and they present a remarkable diversity due to the innumerable objects that compose them, the multiple forms of interpretation, and the diversity of experiences that individuals develop in them (Gieryn, 2000); (ii) the kind of conceptual and methodological anarchy in which the concept of attachment to place is found, as well as the lack of a solid theoretical body that supports its empirical applications (Lewicka, 2011a; Manzo and Devine-Wright, 2014); (iii) the lack of studies on the relationship between the Portuguese people and Portuguese natural parks, namely the Ria Formosa natural park.

The village of Fuzeta and the Ria Formosa lagoon

Fuzeta is a 0,36 km2 small fishing village belonging to the municipality of Olhão, situated in the Algarve, a region of Southern Portugal. According to the 2021 census, the União das Freguesias da Fuzeta and Moncarapacho have 9275 inhabitants, about 2000 of them living in the town of Fuzeta.

The main economic activities occurring at Fuzeta are still related to the sea: fishing, shellfish harvesting (mainly clams), clam farming, and salt production in salt pans. However, tourism, hospitality, and water sports are increasing every year.

The town faces the Ria Formosa lagoon, which constitutes a Natural Park. Fuzeta has two beaches, a small one inside the lagoon and a much bigger one on the exterior, in the sand islands that separate the Ria Formosa lagoon from the Atlantic Ocean (see Figure 2). Nowadays, Fuzeta and its surroundings have been the scene of strong touristification and they became a 'Sun and Sea' destination. In the summer, the population more than doubles due to the number of visitors. (Câmara Municipal de Olhão, 2018). Many of the traditional activities related to fisheries and clam farming are being abandoned, and the old population is slowly being replaced by the growing presence of foreigners who have chosen to live and work in Fuzeta.

Since the 1980s, the Algarve has become Portugal’s favourite holiday destination, for both nationals and foreigners. Consequently, in the last four decades, the active population has shifted from the primary sector to activities directly or indirectly related to tourism (Instituto de Conservação da Natureza e das Florestas, 2018).

Ria Formosa is a salt water lagoon in the eastern Algarve covering an area of 18,000 Hectares that extends from the municipalities of Faro, Loulé, Olhão, Tavira, and Vila Real de Santo António (ICNF, 2018). It is bound to the north by the coastline, which includes salt pans, sandy beaches, agricultural land, and freshwater lines (Caldeira, 2015), and to the south by a sandy dune cord, consisting of a set of islands parallel to the coast, interrupted by six inlets - including the Fuzeta inlet - that allow the entry and exit of seawater and boats (Figure 3). It is the most important wetland in the South of Portugal and, since 1980, it has been on the list of Wetlands of International Importance (Perna, 2005). It has an enormous ecological, scientific, economic, and social value. It includes several habitats, and its biodiversity is internationally recognised (ICNF, 2018).

However, the Ria Formosa lagoon is also one of the most vulnerable areas in Portugal, having been constituted as a Natural Park in 1987 (Domingues et al., 2017) and classified as a Waterfowl Habitat, under the 2009 AVES community directive (ICNF, 2018). The Ria Formosa Natural Park is subject to extreme human pressure, and it is intensively influenced by the touristification of its towns and beaches. Those processes result in significant contemporary changes in its natural, social, and cultural elements.

The attachment of the residents to the Ria Formosa lagoon

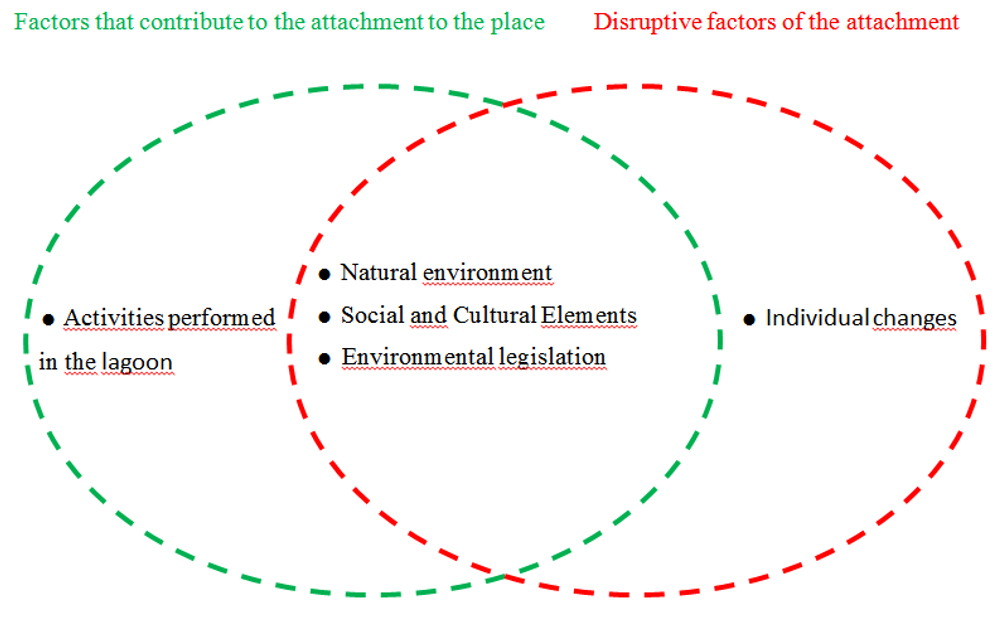

Meanings and values, emotions and feelings, preferences, and perceptions of the irreplaceability of the Ria Formosa lagoon were analyzed through two dimensions: ‘Factors that contribute to the attachment to the place’ and ‘Factors disruptive to attachment’ (see Figure 4).

According to the results, there are a lot of activities that the interviewees like to do in the Ria Formosa lagoon near Fuzeta. Many of these activities can be practiced in the same place and at the same time. Indeed, most respondents highlighted the same idea, namely that in the Ria Formosa lagoon, they can simultaneously practice several of their favourite leisure activities, for instance, fishing and contemplating the seascape, sunbathing while capturing clams or exercising while cycling by the shore.

Oh, man! (The important thing) is to touch the sand and catch the shellfish. Sunbathing is secondary... the beach is more for the enjoyment of catching seafood than for the beach itself. When the tide is high, I’m fishing; sunbathing is very rare. I’ll go fishing with my sons. At low tide, I’ll catch some razor clams, some clams, some cockles, everything (E8, man, 45 years old).

The lagoon is fabulous, and that’s why we like to come here… Will I catch some razor fish? I don’t feel like it! Will I go fishing? I don’t feel like it. Will do I go to (get) the oysters? I don’t feel like it. Will I catch crabs? I’m just going for a walk. I’m just going to row in my boat for a while. It’s all here. That’s why this is so good (E26, male, 48 years old).

All respondents declared they were extremely happy to engage in their favourite activities in Ria Formosa. The vast majority were very satisfied with the way they engaged in these activities, including those who pursued professional activities in the lagoon.

In my activities in the Ria … I have moments (when)... It’s love, the only way to describe it is as love. Those moments that a guy feels are full of love, and a person thinks that he loves it (E6, male, 47 years old).

I like to feel the clams (with my hands) … and when I feel the big ones on the bottom, it makes me happy. I have pleasure catching them. Sometimes I have to stick my fingers (into the sand), and sometimes it’s hard. I like it very, very much. It is a hard life, but I like it, and it is what I know how to do best (E19, woman, 77 years old).

(While windsurfing) Enjoying the elements, the water, and wind give you pleasure and the sensation of freedom. An absolute joy, a great sense of freedom and the joy of harming nothing, taking advantage of the elements to speed up (E21, male, 50 years old).

Some interviewees referred to the Ria Formosa as a place that enables activities that bring a significant income to their families. All those whose professional activities depended on the lagoon mentioned that it is their workplace and their place for leisure at the same time.

I really, really like to catch clams. I can’t stay at home without coming here. Besides enjoying it, I have to come here, I need it (the money) (E19, woman, 77 years old).

All the respondents valued the proximity of the Ria Formosa and the ease with which they could access it from their homes. The lagoon is the place that enables them to do what they like and to feel next to nature.

I’m here (at home), and in five minutes, I’m in the water (E3, male, 55 years old).

We have all the good things the lagoon gives us; it’s also the proximity, we park and even on a very busy day, we can go to the beach (E22, male, 42 years old).

This is unique, the proximity, the space, the fact that you can use it… Even on unpleasant days, I like to go there. It gives me that winter strength to see the colours… I love to see the colours of the water (E6, male, 47 years old).

As a natural environment, Ria Formosa is valued by the interviewees in several respects, namely for its natural beauty, the abundance and diversity of the wildlife, the spectacular landscapes, the sense of freedom, and the peace it provides. All these aspects have led many of its users to consider it to be unique.

We swim among the fish. We are in the middle of nature, enjoying all that, the cuttlefish, sometimes octopuses… What more can we want? (E3, male, 55 years old).

I have visited many places and I think there is nothing like our landscape. I say that we come here to get energy for everyday life. This is pure gold! (E4, male, 49 years old).

What makes me like the Ria Formosa is nature … When it’s sunny on a Saturday morning and I manage to come here, I feel that it frees me up. I feel lighter and better (E14, man, 39 years old).

For all interviewees, the Ria Formosa lagoon has many unique and significant places, such as Praia dos Tesos, Ponta das Pedras, Salva-Vidas, Ilha da Fuzeta, the inlet (where the sea meets the lagoon), and the old inlet. All these places, with their own characteristics, make this area irreplaceable for its users, increasing their attachment.

Fortunately, I (have) travelled a lot, and when I come home from a trip and arrive in Fuzeta during the day, I go to the Ponta das Pedras. It is a fabulous thing. I can go to Mexico or Croatia, and if I arrive during the day, I will go there. I feel that I’ve come home. It’s a need that I have. This place is connected to me (E21, male, 50 years old).

This research also identified meanings and values related to socio-cultural aspects, particularly those related to sociability and a sense of togetherness during activities with friends and family. Many interviewees highlighted the importance of sharing experiences with friends and family, and transmitting knowledge about the lagoon to the younger generations. They mention with joy and enthusiasm the way they share their experiences in the lagoon, and how they enjoy the presence of others when involved in their favourite activities. For some, the company of friends and family is indispensable for certain activities.

I’ve been used to this since I was a little boy (living nearby the lagoon and from the lagoon), and I want to pass this on to my children. I’m trying to do for my children what my parents did for me: teach them how to enjoy this wonderful place and to give them a different idea about nature (E8, man, 45 years old).

Camping in the old inlet: it’s… Heaven!… We can’t live without that conviviality… (E9, woman, 43 years old).

Basically, camping on the beach is a spectacular thing that we do … To see families together setting up the tents, cooking together, parents teaching their children how to catch seafood and octopuses. I find that spectacular. If we don’t do that, what happens? Our culture will be lost (E12, male, 33 years old).

The majority of the interviewees have a very long connection with the Ria Formosa lagoon (since they were born) (see appendix). The number and significance of the references they made to their past seem to corroborate the works carried out within the scope of Environmental Psychology mentioned by Silva (2015), in which strong attachments to the place were identified through memories of experiences from childhood and adolescence. For most, above all the lagoon represents a place of initiation. Many of them still practice some of the activities they started in the earlier stages of their lives, such as fishing, catching shellfish, or camping. They remember with joy and nostalgia some of the activities they can no longer practice, highlighting the importance of some personal experiences that took place there.

I grew up there, on the beach, in the mud, catching lobworms, fishing … It was all there (E12, male, 33 years old).

It’s incredible … the Ria is my passion … I was practically born there. I have been swimming there since I was five or six years old. Bathing in the Ria is already inside my body (laughs). The water has already infiltrated in me (laughs) (E17, male, 64 years old).

These results also seem to corroborate the conclusions of Moreira (1987), according to whom the populations of small fishing towns, such as Fuzeta, tend to have a firm attachment to the places where they were born and live.

This lagoon means a lot to me in the sense that I grew up here, I fished here, I ran there, I walked in the mud, I dived, I did everything (E1, man, 72 years old).

It means a lot to me. It represents all the memories of my childhood experiences (E22, male, 42 years old).

Almost all the participants in this study valued the fact that they live close to the Ria Formosa and cannot imagine themselves living away from it. They express satisfaction and pride in the area where they live. Many consider it to be part of their homes. They attach great significance to this aspect as, for many, it represents home, continuity, happiness, comfort, security and familiarity.

When my clients ask me if I like being here, I reply: so? This is my garden (E12, male, 33 years old).

The lagoon is my home (E21, male, 50 years old).

Here, we are at home... I think I couldn’t live without this. It’s a small corner that isn’t found anywhere else (E24, woman, 19 years old).

Regarding the village of Fuzeta itself, most of the interviewees believe that Fuzeta maintains its authenticity and tradition, compared to other towns in the Algarve.

In other tourist areas, local people have almost disappeared. There are just tourists, there’s no local population except to work. But Fuzeta still has its fishermen. They (the tourists) like to see the fishermen, and when they go to the (waterfront) restaurants and see the boats coming, that gives them something captivating. It’s typical, that’s what they like: typical things, not artificial things. This is people’s everyday lives (E3, male, 55 years old).

Along with the intense feelings of familiarity with the place, many interviewees referred to the fact that they feel that they, themselves, are part of the place.

I’ve been working in the lagoon for over 20 years or so. It’s a part of me because I live in Fuzeta, 100 metres away from the lagoon (E11, male, 61 years old).

The lagoon is a part of me. It’s a part of all that were born in Fuzeta. It represents a lot for us. It’s our backyard, It’s like an organ of our body. It is part of us (E26, male, 48 years old).

Some interviewees mentioned a strong feeling of ‘ownership’ towards the lagoon, considering that it belongs more to the residents than to the visitors. Therefore, the competent authorities should legislate to protect the residents’ rights to enjoy it.

They (the authorities) shouldn’t give any more (beach) concessions, because I think that the locals have the right to enjoy our nature, we are the ones who have been here for long. I believe we have the right not to have the whole beach privatized, right? (E3, male, 55 years old)

This is the landscape we are used to, this (is) ours. Other landscapes must be someone’s, but this is ours. This is the one we are used to seeing every day. We have the perception of this being ours, of knowing the things that happen around us (E13, 46 years old).

All the respondents mentioned the fact that they felt that this place is irreplaceable. They stated that they practice certain activities only in this area - such as sunbathing, hiking, catching seafood, camping, and fishing - and they won’t do the same elsewhere. These results also indicate that there is a great dependence on the place.

This is the place where I was born, and it’s where I want to die. As I used to say: ‘I only leave dead’ (laughs) (E4, male, 49 years old).

To leave the lagoon? Don’t you even think (about it) (laughs)! This is incredible ... My passion is the Ria Formosa. That’s where I was born. I can’t live without it (E17, male, 64 years old).

Me leaving the lagoon? Never! No way! I want to finish my days here (E10, male, 76 years old).

All respondents mentioned at least one aspect related to their future expectations regarding Ria Formosa. As we have seen above, these expectations for the future strongly contribute to feelings of place attachment.

Soon I will open another business where the new apartments are being built. But it is also in the Ria (E15, woman, 62 years old).

I have the project of living on a boat. Not for now, but I am thinking very seriously about living onboard with my family (E8, male, 45 years old).

Disruptive factors to the attachment to Ria Formosa

This research identified some factors that negatively interfere with the activities that the interviewees practice in the lagoon. These may constitute disruptive factors concerning their attachment to the Ria Formosa. Some of the factors even seem to threaten the practice of certain activities or imply their displacement to other places.

Despite the fact that the interviewees contradict each other concerning the disruptive factors of their place attachment, the aspects most mentioned are related to human pressure and tourism development, such as the policies of beach and clam farming concessions (too many beach and clam farming concessions), the pollution of the lagoon, the excessive number of people on the beaches, and the number of boats and motorbikes navigating on the lagoon. Some of them also fear the construction of more tourism infrastructures - such as an apartment resort - in the centre of the village. Some of them mentioned as disruptive factors of their place attachment the inappropriate behaviours of the tourists during the summer season, and their avoidance of the beaches during that time of the year.

There are more and more tourists and the population here is getting older. I’m afraid that, one day, Fuzeta will be finished as we know it. I wouldn’t like them to build more parking lots or apartment buildings for tourists. I think it would be bad for the local population and for those who enjoy Fuzeta (E24, woman, 19 years old).

Many participants in this study referred to the degradation of the natural environment, such as the decline in the quantity of fish and shellfish, the increasing pollution of the water and, mainly, the erosion of the barrier islands. According to them, if this area continues to be poorly managed in terms of dredging and sand replacement on the barrier islands, there will be very negative consequences for the Ria Formosa and to the fauna and flora. There is a strong feeling, for instance, that the beach of the Ilha da Fuzeta (the sand island in front of the village) may disappear if the sands are not replaced after the winter storms

If they don't put sand in the right places, the island will disappear. This will affect the population because we will lose this beach and we no longer have the option of choosing the beach we want to go to (E25, woman, 18 years old).

I negatively anticipate my future. There are fewer fish, less seafood, fewer places to fish, fewer places with shellfish. So, the future is dark (E1, male, 72 years old).

In relation to fishing, we, the fishermen, think that over time the bigger boats have to be banned, otherwise, they will finish off everything (E18, male, 48 years old).

We believe many of them don’t even realize that some of those negative effects on the ecosystem are also a result of their own action. This means that the degradation of the place is, at least in part, the result of the aggregation of many individual practices. They seem to illustrate the process that has become well known in Economics and in Environment Science as the 'Tragedy of the Commons': the result of the collective use of common resources without restrictions. Although this was not the objective of this research, a very interesting research question would be: 'what happens when the natural deterioration is also the result of the action of the own community that attributes significance to the place?' The answer to this question - to be answered in a future research - would need another type of questions in the interviews.

Most of the informants tend to blame third part actions such as tourists’ behaviour, tourism development or the action of the authorities. In fact, paradoxically, the excess of regulation, legislation, and the control of the authorities were also pointed out as disruptive factors. Regarding this aspect, predictably, there are contradictory statements. On the one hand, some interviewees showed satisfaction with the measures that currently protect the ecosystem of the lagoon and consider that they are still insufficient; on the other hand, some mentioned the existence of oversight and an excess of legislation that causes them some apprehension.

This lagoon is plundered by lots of people who live professionally from looting it. There is no inspection. Nobody controls anything. It is pure degradation (E1, male, 72 years old).

One no longer knows if it’s forbidden or not to catch cockles or clams. I heard that people were being fined. I’m already afraid. I gave up (E5, male, 64 years old).

According to Queirós (2001), this type of contradictory opinion is very common in the populations that live next to or inside Natural Parks. The characteristics of these sites give them both the status of protected areas and create a great demand for the practice of certain activities that compromise their ecological balance.

Conclusions

Various disciplines have increasingly studied the importance of the connections of people with the natural environment, and the concept of place attachment has been central in these studies. The literature review enabled a theoretical clarification of the concept of place attachment that aimed to contribute to the improvement of this tool for future studies on the relationships between people and places.

The majority of the aspects of the attachment of the people from Fuzeta to the Ria Formosa lagoon identified in this study were also identified by other authors who carried out similar empirical research in analogous contexts. This implies that, regardless of the characteristics of the place, there are types of place attachment that are common to all human beings.

The existence of several types of attachment to the same place was defended by authors such as Low and Altman (1992), Lewicka (2011b), Gustafson (2014), and Manzo and Devine-Wright (2014). For all our respondents, several types of attachment to the place also coexist. The general attachment of each of the inhabitants of Fuzeta to the Ria Formosa Lagoon results from the contribution of several specific types of attachment.

The formation of attachment to a place is a highly dynamic phenomenon, as defended by authors such as Low and Altman (1992), Lewicka (2011a), and Devine-Wright (2014). There are also factors that cause it to decline or even break. In this sense, contributory and disruptive factors are two sides of the coin, and both are equally important to understand attachment to place.

This research identified aspects that could temporarily change attachment to the Ria Formosa lagoon, as well as aspects that could actually destroy it forever. This is the case with regard to the ecological imbalances, and the lack of maintenance and surveillance by competent authorities. These aspects are destructive of attachment because they could, in the future, preclude access to some important places, and hinder the practice of significant activities.

The meanings and values the interviewees of this study attribute to the Ria Formosa lagoon when practicing their activities or remembering their past experiences, the emotions and feelings involved, along with their perception of irreplaceability, lead us to conclude that these people have developed an extremely strong attachment to this place. They feel the lagoon is not only their place of work or leisure, but also their home, and even a part of their own bodies. Most of them are so attached to the Ria Formosa lagoon that they cannot even imagine themselves living away from the place they love so much.