Introduction

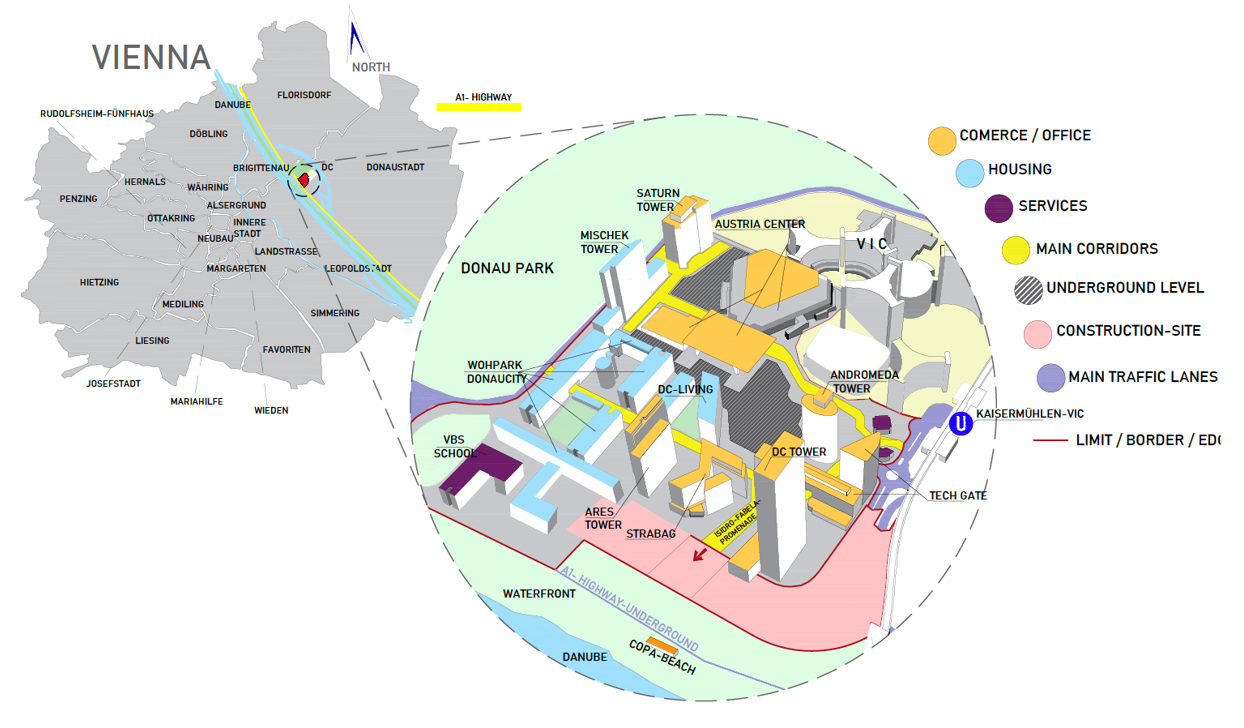

Come to Donau City on a sunny afternoon and the geometry of the place, its wide and empty pedestrian streets, the importance of contemporary glass architecture and the succession of towers will surprise you. The area with its modernist setting and its predominantly concrete environment gives the impression of emptiness and underuse. Donau City is located in Vienna, Austria, on the East bank of the Danube River next to the United Nations headquarters. It is one of the first major redevelopment projects launched in the late 1990s by the capital city within the scope of a public-private partnership. Donau City is home to approximately 3000 residents and hosts more than 12000 workplaces1. The development is still underway with the construction of the Danube flats, a 160 meters high luxury residential building.

Since the 1990s, urban redevelopment projects have become a common trend applied by most cities worldwide. Whether megaprojects with a predominance of high-rise buildings and starchitect symbolic features, reconversion of buildings in the city-centre with heritage dimensions or new-build urban centres in metropolitan outskirts, these projects all aim at attracting and housing new populations while fostering new socio-economic dynamics (Fainstein, 2008; Guinand, 2015, 2017b). The new-build area of Donau City is such a case. Behind the aesthetical attention paid to architectural forms, the open spaces’ perception and appropriation by its residents and users raise concerns.

Drawing on data from photovoice interviews (Woodgate, Zurba & Tennent, 2017; Lombard, 2013; Kolb, 2008; Wang & Burris, 1997) with residents and users and cross-analysing them with non-intrusive observations, reviews of official plans, reports and web-based marketing materials, we situate the qualitative examination of this site within the context of new-build public-private partnership redevelopment projects in Europe and more specifically in Vienna. We aim at analysing the intrinsic qualities of this specific urban environment by understanding how residents and users perceive, decode it (emic perspective) and make sense of this everyday practiced and lived space (Stedman et al., 2004; Bigando, 2013; Schoepfer, 2014). We aim at doing so using the photovoice interview method implemented within a citizen science perspective (Heckers et al., 2018) as a process of co-construction of knowledge (Codesal et al., 2018; Wang & Burris, 1997) to achieve a better understanding of lived space (Lewin, 1936; Lefebvre, 1991) within redevelopment projects (Erfani, 2020). Bohnsack underlines the importance of images for practical actions as they are implicated in all systems of meaning. Social reality is not only represented by, it is also constituted or produced by pictures and images. They provide orientation for actions and everyday practices (2008). Resorting to photovoice methodology also opens a political voice in the construction and design of the built environment (Möller, 2010).

For instance, results stemming out of informant’s photographs underlined the importance of scale in experiencing open spaces as well as the low social interactions among residents and workers. For city authorities, planners and developers, these open spaces are an important feature of life quality and economic development (Madanipour, 2014). Yet, the quality of these urban environments should be critically examined and understood from “within” as this dimension tends to be downplayed once building operations have been completed.

We begin by introducing the conceptual framework upon which we based our research question (Section 2). We continue with the description of our methodological approach and the case study (Section 3). We then turn to results, analysis and a discussion of the lived space of Donau City (Section 4), ending with a conclusion (Section 5).

Conceptual framework and research question

Urban quality and public-private redevelopment projects

Public authorities as well as private actors involved in territorial production have been increasingly concerned about ensuring a high urban quality level for the space produced (Mandelli, 2019). If some authors mention that it is related to land value gains obtained (Loughran, 2014) and new audiences’ attraction (Guinand, 2017a), others stress urban quality as an important feature increasing life quality in urban settings (Lynch & Rodwin, 1958; Gehl, 1971; Gehl & Svarre, 2013; Wolfe, 2019). While the study and regulation of urban quality - legibility, relationship to forms and volumes (Lynch, 1988), life and amenities (Jacobs, 1992) or treatment of scales (Gehl, 2010a) - are not new (Talen, 2009), all these parameters are challenged by climate change incentives for a sustainable, dense and qualified city as well as the increasing pressure of urbanization, migration influx (Crisp et al., 2012) and budget constraints (Guinand, 2017).

Since 2008, pressure on public budgets in Europe has strengthened new public-private partnership arrangements in the performance of tasks traditionally assigned to public authorities or third-party actors, such as quasi-public organizations. Public authorities in Europe and around the globe have set up urban planning and legal tools to facilitate these partnerships in order to produce and develop territories, often on publicly owned land bases. It is the case of Donau City, which used to be a former dumping site. This new urban management is often related to efficiency, profitability, innovation and the implementation of new command functions (Harvey, 1989). It is also based on the financial investment capacities and know-how of private actors. While offering new tools and processes (Marty et al., 2006; Fainstein, 2018), these partnerships have at times been criticized for undermining the foundations of urban quality such as equity, democracy and diversity (Fainstein, 2010; Miraftab, 2004; Redak et al., 2003). Negotiations between public and private parties are decisive as private interventions, depending on their objectives, can influence urban quality (re)development, such as location of public spaces, urban furniture and design, greening, amenities, services and functions, social-mix, etc., which, in turn, might influence the practices, uses and accessibility of these spaces and the overall life quality.

Urban redevelopment combines economic, social and cultural challenges, while also having to pay attention to urban forms and symbolic dimensions, in terms of image and territories (Guinand, 2015). This implies outside settings, layout of spaces, street design and pedestrian frames, diversity of the amenities offered and atmospheres that emerge from the site. A wide range of scholars (Gehl, 2010a, 2010b; Lynch & Rodwin, 1958; Jacobs, 1992; Carmona, Marshall & Stevens, 2006; Da Cunha & Guinand, 2014) has investigated the quality of urban space. All those different studies, independently of one another, underline the importance of 3 dimensions: 1) the urban design (form, function, use, scale), 2) the environment (ecological dimension) and 3) the actors participating in the project (governance, negotiation and management processes) (Guinand, 2017b). These dimensions represent what Carmona et al. (2008) have identified as the desirable and universal positive qualities (p.15). Alike its underlying determinants, urban quality is not self-evident and it differs according to the actor who defines it. It includes a strong subjective dimension conditioned to each individual’s system of thoughts and values. Consequently, as argued by Lynch (1988) the overall patterns of qualities will influence the space perception and reception, meaning that downplaying certain features might undermine the overall quality of the open environment.

Although the environmental dimension and governance bear consequences on the resulting quality of the studied urban environment, in the scope of this paper, we focused on the first dimension thereby investigating notions of form, function, use and scale and how they were expressed in the informants’ photographs (Table 1).

Table 1 Urban quality dimensions grid

| Perceived urban quality through: | |

| Form | Architecture / Landmark/ Volumes / Density / Settings / Design |

| Function | Social / Economical / Political / Environmental |

| Use | Appropriation / Social uses |

| Scale | Micro, Meso, Macro / Interrelations / Connections |

Credits: Sandra Guinand based on Da Cunha & Guinand, 2014.

Urban quality might be “common” ground in urban design and practices, recent scientific studies show however that, in the case of provision of public spaces, it tends to focus more on functional and aesthetic concerns rather than on space provision which takes into account local values and spatial perceptions (Guinand, 2015; Mandeli, 2019). It is imperative to note that intangible dimensions actively participate in defining the quality of the urban environment (Carmona et al., 2008).

Lived space and the reception of the built environment

Examining lived space, we draw here on Lefebvre’s theory of space production. According to Lefebvre (1991), space is a dynamic process. Social processes shape the form of space. In turn this form also sets and influences social processes. This means that when analyzing the built environment, attention is paid as to how it shapes behaviours in being attentive to design, architecture, etc. But intangible dimensions (codes, symbols, etc.) imbedded within the built environment are equally relevant (Tuan, 1977). They provide meanings and frame place’s identity (Twigger-Ross et al., 2003). Lefebvre (1991) identifies 3 dimensions that one should be attentive to when looking at space: 1) perceived space (through spatial practices); 2) conceived (designed) space (through representations of space); 3) lived (experienced) space (through representational space). These dimensions are not dissociated: they participate in space production and are part of one dynamic.

Perceived space corresponds to practice of space, linked to the relations of production of this same space: how it is ordered and how it is developed. It leads to the conceived and designed space that is translated through signs, codes and norms. This designed space represents the space of those who build it: planners, technocrats, developers, etc. Perceived space is also that of users, residents who practice and live in this space on a daily basis. The space is therefore also charged with references that act as landmarks and codes for spatial representation (Lynch, 1988). It is the space that individuals try to appropriate and modify accordingly, which, in turns leads to the construction of its representation and experience. The users’ reception and sense making is an important aspect in order to get an emic (Olivier de Sardan, 1998) understanding of space. It is this latter dimension that we investigated analyzing Donau City as a place study (Brubaker, 2003).

Studied area and methods

This paper stems out of an exploratory citizen science project (Hecker et al., 2018) conducted during a 6 months period (April-September 2019).

Citizen science approach

Citizen science is a field in sciences that supports alternative models of knowledge production (Hecker et al., 2018, p.2). It was first coined by Irwin to describe research collaboratively conducted by professional scientists and the public (Irwin, 1995), while Bonney referred to the term for avian projects research involving members of the public (1996). This approach has proved useful at strengthening scientific research by engaging in alternative sources and data gathered by citizen participants. It has also been acknowledged within the scientific community as an appropriate approach to answer specific research questions and meet scientific demands (Heckers et al., 2018, p.4). In the scope of our research, the citizen science approach coupled with photovoice interview was used to engage residents and workers in the research and position them as the main providers of data (Ellul et al., 2013). Moreover collecting photos from informants and listening to their narrations, turn them into active participants as they consider the research question and identify issues and topics of interest to themselves and their community (Kolb, 2008, p.6). In our research, we treated users’ subjective experiences as expertise of the environment they practiced on a daily basis.

Working with photography

Following Stedman et al. (2004), we used photovoice interviews (Wang & Burris, 1994, 1997; Woodgate et al., 2017; Lombard, 2013; Kolb, 2008) to assess elements or forms, that fostered place attachment, uses and appropriation or rejections and that altogether framed the lived space. First pioneered by Wang and Burris (1994, 1997) in community-based participatory research with marginalized populations in the mid-1990s, photovoice interview is praised for its collaborative dimension and characterized by the use of photographs taken, and interpreted by informants. They are the basis from which the interview is conducted. In our case, the photos were supported with captions that reflected on issues or elements significant to the informants and how they viewed themselves and their environment. These short-written statements (2 to 3 lines) together with the titles helped understanding the photograph’s contextualization and the informants’ intent. Taking and bringing in their own photographic image production allowed informants to directly intervene in the research’s structure and interview process. The method provided a means for users, notably residents and workers, to input their thoughts and social constructs to the research process and its outcomes while facilitating personal accounts that might have been difficult to gather with a more conventional method. It was also used as a way to gather affective connections between people, their environments, and life situations (Kolb, 2008; Lombard, 2013). Although the photography approach is still debated in urban studies (Krase, 2007; Conord and Cuny, 2014; Färber & Jarrigeon, 2020), we argue that it is particularly useful for scholars engaged with urban related topics, as it offers an insider perspective and perception of urban daily life experiences. Moreover, as stressed by Möller (2010) these citizen-photographers bring in their voices, emotions and statements assessing their urban environment, which could be useful information for urban planners and city officials.

Methods

We situate our research approach within visually grounded theory methodologies (Suchar, 1997; Mey & Dietrich, 2016). This means that emphasis was given on constant comparison between our data and theoretical sampling strategy (our conceptual analytical grid) driven by our general research question (Mey & Dietrich, 2016, p.4). In order to conduct our research, we randomly identified 13 people (Maxwell, 2009) based on a call posted on the Facebook page of the Michek tower housing community, through posting ads in buildings’ hallways and through networks and acquaintances. 6 of them were individuals working on site and living outside while 6 were residents. 2 were residents working on site. The sample of people comprised 2 children (8 and 10 years old), 4 young persons (20-35) and 4 middle-aged people (45-60) as well as 3 retired individuals (70-80). This combination of individuals gave us a certain degree of diversity in background characteristics in order to capture variation in experiences, attitudes, or preferences, a most valuable element relevant for our research question (Boeije, 2010).

A first meeting was arranged to explain 1) the scope of the research; 2) how our collaboration would take place; 3) present the method’s protocol and ethical issues. The meeting took place (with 1 or 2 researchers) either at the informant’s home or in an identified place located in Donau City. This first meeting was essential as to generate an atmosphere of trustworthiness, which enabled the informant to feel later at ease to share her/his personal opinions, feelings, everyday experiences (Schoepfer, 2014). During this meeting, we discussed the participant’s everyday life and practices. This helped prepare and structure the photo-walk by raising the informant’s awareness about mundane issues. After that first meeting, the participant would take a photo-walk2 alone that represented or was typical of her/his commonplace practice in Donau City. Based on previous studies (Latham, 2003; Pyyry, 2013; Schoepfer, 2014), we choose photo-walk because walking encourages participants to look at otherwise unnoticed mundane dimensions and patterns of personal and social life (Leon De & Cohen, 2005). Informants were asked to take 6 to 10 pictures and to accompany them with 2 or 3 short sentences. No specific aesthetic or frames for the photographs were recommended.

The interview took place after this first stage and the photographs sent to us. The encounter (with 2 researchers was set at the informant’s place, a café chosen by the participant or the university. Participants expressed themselves in English or German. A common interview protocol was followed. We first asked the informants to organize and order their photographs. This order could reflect their walk sequence or themes that were exemplified and emerged through the process of place perception. We then proceeded to the interviews organizing them around 1) the walk, 2) the selection of photographs and 3) the content and meanings associated. This loose structure allowed participants to tell “their” story (Möller, 2010) revealing the mental structure of their environment (Lynch, 1988). The interview lasted approximately 1 hour and was concluded with reflexive questions on the participation in the research. We then followed an inductive approach (Hennink et al., 2020) to conduct the analysis of our interviews. In a first step we adopted open coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) identifying the recurrent themes stressed by the informants when reading and commenting on the photographs during the interviews (Charmaz quoted in Suchar, 1997, p.38). We then proceeded to establish connections (focused coding) between the identified categories (open codes) as a means to select a new set of “core categories” identified from our data corpus (Strauss & Corbin, 1990; Suchar, 1997). In order to verify our results, we proceeded to the triangulation (Maxwell, 2009) of our conclusions with second hand data, such as scientific literature on Donau City, content analysis of web-based materials and institutional materials (plans, brochure, reports, etc.).

Contextualizing Donau City

The development of Donau City started in the mid-1990s under the Vienna Danube Region Development Corporation (WED). It was planned as an economic engine of a tertiary economy to position the Austrian capital internationally. This public-private partnership was composed of government authorities (City and Land) along with Austrian banks and insurance companies before becoming the sole property of Bank of Austria. Today, the WED is entirely in the hands of the UniCredit financial group, which over the years has sold several properties on this site. The urban composition although implemented in the second half of the 1990s, is strongly characterized by a functionalist approach typical of the 1970s, with a dominant high-rise landscape, and separated levels for pedestrian, motorized flows and technical infrastructures. The continuous development of the area has witnessed various masterplans3 and the redevelopment project is still underway. Donau City hosts office towers, high-end condominiums as well as subsidized housing such as Wohnpark Donau City (190 apartment units). Consecutive land ownerships and layers of construction have blurred the management and responsibility of spaces previously in the hands of the WED (Guinand, 2017b). Above all, they have disrupted Donau City’s readability (Lynch, 1988) and fragmented is social and spatial organization.

The map uses German denomination and spelling. DC is the acronym for Donau City and VIC for Vienna International Centre where the United Nations’ headquarter is located.

Results and discussion

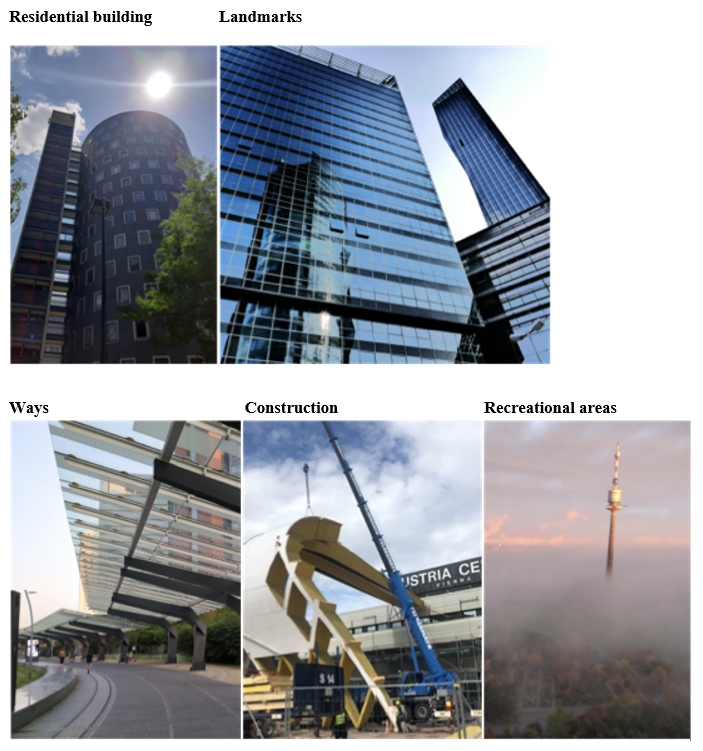

We witnessed significant differences among participants’ photographic approaches, the itinerary taken, the activities and the open or private spaces captured. We organized our findings around “residents” and “workers” that could both fall in the users’ category. Recurrent identified elements were broken into 3 categories (open coding).

Images and discourses associated to form(s);

Images and discourses capturing the function(s) of the spaces that could be expressed in terms of different identified uses;

Images and discourses expressing scales’ experiences.

Among these categories, we identified core elements underlying little open space appropriation and lack of social interactions in the different open (public) spaces punctuating Donau City:

1) A common feeling of emptiness experiencing open spaces;

2) Common discourses on the role of climate, more particularly the wind, and its impact on open spaces;

3) Little spaces for social interactions among the “users” especially between the 2 groups “residents” and “workers”;

4) A lack of social interactions amplified by the relations to urban scales between residents and workers.

In the following section, we discuss more thoroughly the findings and their significance following these 3 categories and 4 themes.

4.1. Looking at and discussing urban forms

4.1.1. Feeling of emptiness

Describing their daily-life environment, informants often presented locations associated with feelings of emptiness. Reasons evoked or explanations given related to the lack of amenities, and design that would invite them to stay. For some, there is simply “nothing” there (in the open space) (Figure 2), while others identify some places as being located “outside” of the core of Donau City.

“I’m not very often there but I like the place because it’s just very open. Totally empty, nobody ever goes there. But it’s part of the outside” (Informant 2, 01.07.2019).

A lot of these areas located at the district’s edges are perceived as left out as they are described as lacking any urban or natural elements that would attract people to linger, pause or gather. Some of these places have lost their significance and function through the planning and development process. The successive masterplans show, for instance, projected developments that were later abandoned or modified. One resident referred, for example, to stairs that were historically planned as part of a former square. Today, these stairs lead to a dead end and residents and users not familiar with the story behind the actual design tend to be confused by this setting (Figure 3).

“Links gehen so Treppen und die gehen bis zur Autobahn und dann ist nichts. Da sind zwei Treppen, die gehen rauf und die führen ins Nichts. Und das war, weil die Schule sollte ursprünglich niedriger werden und die Autobahn überblattet das, dann hätten die Stiegen in die Schule irgendwie geführt (...)4” (Informant 12, 21.08.2019).

Showing us a playground located next to a local pediatrician and businesses (Figure 4), one worker was surprised by the sheer absence of children in open playgrounds of Donau City. According to informants, most playgrounds lack design quality, imaginative settings and any invitation to stay. Moreover, they do not offer sun or wind protections.

“Because it is empty, it’s actually “after hours” like around 6pm and there are no kids. (…) Then, you have a playground and there are no kids to play. And the weather was nice that day, so... Probably in any other country you would have kids playing soccer, running around, being annoying. It caught my attention because it is empty” (Informant 6, 31.08.2019).

The conceived spaces of Donau City contrast with the ones perceived and lived by the users and the workers. Spaces have been planned and designed as “functional”, which tend to lack imaginative dimensions undermining appropriation or any incentive to do so - such as sitting.

4.1.2. The wind factor

Wind in Donau City is a well-known problem that is often reported in Viennese media. Each new building in the area contributes to strong downwind reaching Donau City Straße, the main (central) street connecting housings and offices to the subway station. Looking at the photos of informants, we heard stories of residents or workers going home or to their office and fighting against the wind. These accounts underline how weather conditions can severely impact walking and more generally outdoor experiences.

“An Tagen, wo es windig ist oder stürmisch, gehen wir eh alle vor. [...] Unten im Kollektorgang, wo die Autos sind. [...] Die Kinder genauso, wie wir. […] Gerade um 7:30 Uhr in der Früh, wenn sehr viele Leute gehen, dann geht man kaum alleine, dann gehen alle nach unten [in den Tunnel]”6 (Informant 13, 12.08.2019).

Residents qualify windy episodes as dangerous. They look for safer solutions to get from one place to another. On stormy days, some even find that walking along the Kaisermühlen highway is more secure than walking on the main street. Car traffic as well as utilities infrastructures are located underground. Although not conceived for pedestrians, on a stormy day, residents prefer using the private pathways, staircases or garage entrances to go underneath and walk along the highway to get, for example, to the subway station (Figure 5).

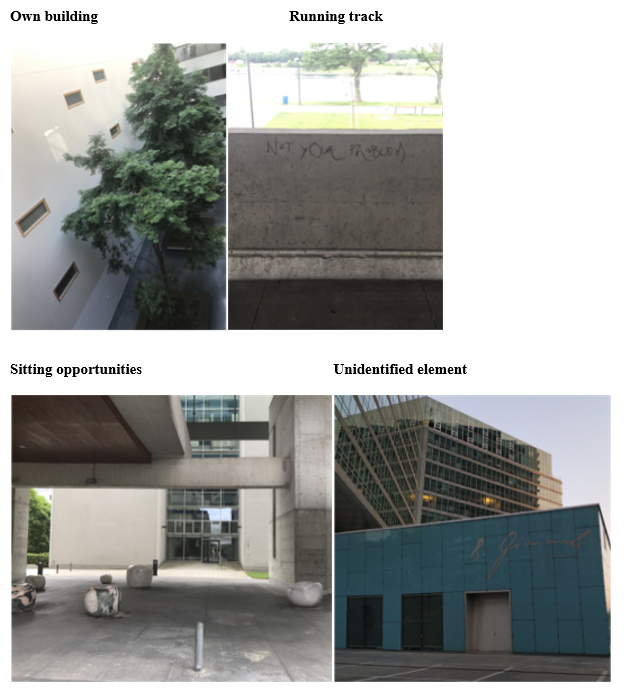

4.2. Functions of a daily-lived neighbourhood

The photographs taken by workers mostly showed us places for breaks, lunch, meeting and “after hours” while residents’ ones illustrated their housing buildings, their running tracks, and some places to sit and relax (ex. seating areas or public squares) (See Appendix 1 for the photographs). Discourses and pictures showed how social temporalities (in our case most exemplified through working hours) structure the spatial relation the workers have with their surrounding environment and how it plays on the “inside” and “outside” social divisions. While discussing concrete functions, residents and employees identified larger areas separate from one another. For instance, employees divided the area according to patterns such as: work, transit areas, enclosed areas and the waterfront at the edge of Donau City (Appendix 2). Some even stated that the modernist designed buildings in Donau City only serve as places for work despite the district being planned as a mixed-use area (City of Vienna, 2010). Several employees identified dead ends at the edges of the area and spaces that they depicted as being in transition, underlining the perception of barriers and disorientation. Workers recounted moments of trespassing these areas and being stopped and disoriented by the absence of proper signage systems. Since the interviews were conducted during the summer, most of them mentioned the waterfront at the New Danube (Neue Donau) for leisure in order to escape their work area (Appendix 2). While seeking out the waterfront they recall transiting through prohibited areas. These experiences emphasize how design and planning can be misleading for the users and create confusing spatial episodes.

Residents organize the neighbourhood around their residential building, where they spent most of the time. They spatially organize their district around identified landmarks, which give a geographic reading of the area. For instance, they mentioned looking at the local architecture and using prominent buildings for orientation. Furthermore, instead of providing visitors orientation through street names, they would point out to salient buildings. This practice allows them to spatially position themselves and their interlocutor within the area.

Residents arrange the area into paths to and from their home, which form an organised grid. Construction sites are perceived as dead ends and blank spots that interrupt their grid especially in recurring construction periods (Figure 6). They quickly adapt by finding alternative routes (Appendix 2). They know shortcuts and are aware of construction sites. New construction sites thus come as a disruptive spatial phenomenon blurring their mental map.

Both groups enjoy the recreational areas located at the edges of Donau City. While residents are very familiar with the routes to these areas, employees tend to choose spaces they best know the way to, such as Copa Beach. Residents and workers have their own understanding and perception of the area that they tend to mentally order according to functional features. For instance, residents identified the area outside the Wohnpark Donau City housing as dedicated to work only, while none of the workers knew that the big green recreational area, Danube Park (Donau Park), was located just behind the housing towers within walking distance. They also experience the area within a functional separation of daily life practices: grocery shopping, having lunch breaks, etc. that tend to limit their interactions. In fact, they did not refer to or talk much about sharing open public places with one another. They mostly identify these open spaces as transit areas rather than meeting places.

“There are some ways… they are like cuts” (Informant 5, 01.08.2019).

4.3. Scaling experience and the notion of comfort zones

4.3.1. Depicting the scales’ experience

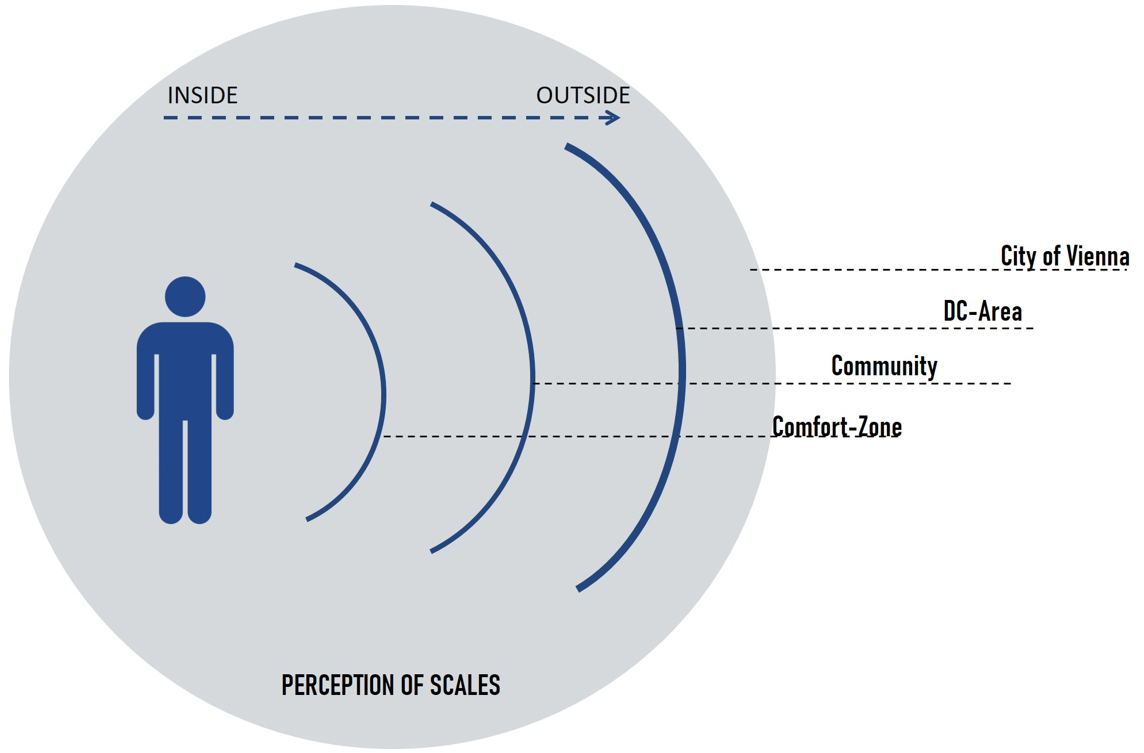

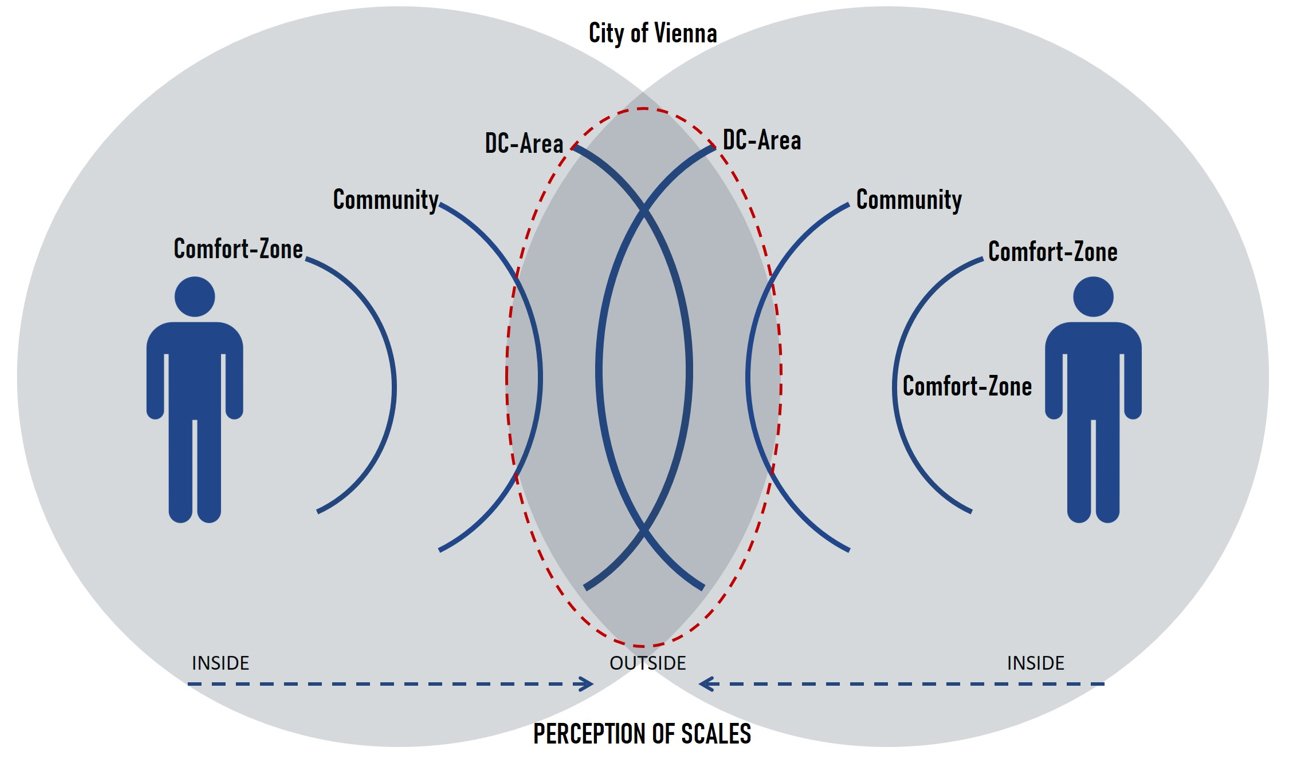

One striking element that came out is how the participants positioned themselves as well as their immediate environment in regards to their overall surrounding. The photographed elements and their description stressed the importance of scales. Scalar ratio and references clearly structure their daily relationship with their environment. They organize their daily space and establish features that work as codes and bring meaning to their surroundings. All informants expressed scales in an inside versus outside relation. They also described how these scales interacted and were interconnected.

Informants’ results presented elements or particularities captured from the open space, which allowed us to identify 4 scales with this inside-outside relation (Figure 7). These perceived scales are also formally mobilised in the work of professional planners and designers (Pafka, 2020). We conceptualised the micro-scale as being the users’ “comfort zone”. It usually refers to the informant’s apartment, balcony, cafeteria or office. This comfort zone reveals place attachment in which feelings are a central feature. The second scale underline elements of a community structure, related to groups or buildings that capture place attachment (Altman & Low, 1992) that materializes in space. The third scale characterizes the neighbourhood identified as the area of Donau City. It involves representations and feelings to the continuous changes experienced within the area. Finally, the macro-scale represents the city of Vienna’s landscape. It features means of connection between the comfort zone (micro-scale) and the macro-scale.

Residents and employees of Donau City expressed different perceptions of the inside versus outside relations. For instance, residents depicted their apartment or balconies in direct connection with the area of Donau City in an inside-outside relation. Workers, on the other hand, tended to present their cafeteria or office as exclusive inside spaces connected to the Viennese urban landscape. For both informants, these places underline feelings of “ease”, “safety” and “coziness” (Figure 8). These spaces are linked to the notion of stability (Brown & Perkins, 1992). They are representative of sites from which residents and workers can observe and behold the outside without experiences of disruption or disturbance. They also behold intangible dimensions: meanings through personal or group experiences and memories.

“Ja, also fast immer wenn ich weiß, dass ich mich hinsetzen kann aber auch wenn ich nur weiß nach Hause zu kommen. Ich habe mich immer gefreut nach Hause zu kommen.”8 (Informant 9, 12.08.2019).

Employees often expressed an inside-outside relation linked to their comfort zone in relation to the macro-scale. They mostly depicted connections through views. One informant explained that the view from his office connects him physically and emotionally to the city’s landscape (Figure 9). From his window at work, he is able to identify landmarks that help locate his neighbourhood and relate to his home. The view then brings back positive memories and feelings of his place.

“That was important to capture because it is such a, well it is my daily view. It leaves a stronger impression of Donau City for me. The fact that I can look out at the river and I can pick out the buildings all throughout Vienna (...) I’d say it makes me feel more connected to the city.” (Informant 1, 05.07.2019)

For the second scale, residents expressed their belonging to the area’s community by associating it to the specific features of their building. We witnessed a community identity construction process enabling residents to distinguish themselves from the rest of the area that qualifies as their neighbourhood (Figure 10). They present themselves as being located in the “inside” in comparison, and in relation to, the neighbourhood. In a broader comparison they perceive the city of Vienna as being “the outside”. Except for the individuals working at the United Nations Vienna International Center, identification of workers with their corporate building as a symbolic element of their working community was less salient. The perception of scales by United Nations’ personnel reduced to their building, is due to the specific geography of this complex: a secured and enclosed enclave located at the edge of Donau City. This location and setting has been very influential on the perception of residents on the complex: they have always considered the United Nations’ building as being beyond the border of Donau City rather than being part of the area.

“Und wir sind eigentlich eine der wenigen Siedlungen [in Wien], die individuell sind. Das kann man schon sagen (…) Zum Beispiel Großfeldsiedlung ist wunderschön jetzt hergerichtet, aber trotzdem alles Gemeindebau. Ja, haben nicht so Highlights so wie wir. So wie Stiegenhäuser, so wie Fassadenbemalung vorne an der Front. Haben Sie schon gehört? Das hat ein Schriftsteller mit einer schwarzen Tinte geschrieben: Original österreichische Texte.”10 (Informant 8, 16.07.2019)

While discussing scales of neighbourhoods, residents highlighted the ongoing construction of high-rise buildings. They described the continuous change of their surrounding as a never-ending process accumulating new vertical layers rather than horizontal ones. For some, it triggers their imaginaries by making references to and comparison with cities such as New York, Chicago, etc. underlining the feeling of living in a modern and high-tech environment. The architectural style and the continuous construction clearly influence the perception residents and workers have of this environment especially when comparing it to the city-centre Habsbourg’s buildings. They also clearly and easily position the area in the urban development chronology of the city (Figure 11).

“I don’t pass exactly this place, but I wanted to make it for you because I find it very special. This is the view, which I have from this way. This is my classic view. What I see this way and I find that this church is exactly the contrast of DC. You see it from many places so it’s always somewhere in the background. You see this kind of old park and it’s always contrasting to the major park, which is very high-tech so that’s why I wanted to particularly take it for you.” (Informant 2, 01.07.2019)

As mentioned, the macro scale’s perception is strongly influenced by views or vantage points. For Viennese standards, Donau City’s (housing) towers are very high and detached differing from dense settlements more commonly found in the inner city. On top, they offer a wide panorama. Exceptional views enable residents and workers to contrast the inside of the architecturally unique Donau City with extensive outside areas ranging from Vienna, the Vienna basin and hills to the Schneeberg, a mountain in Lower Austria that can be hardly seen from other areas in Vienna (Figure 12). These views allow the residents and the workers to quickly relate and identify themselves as belonging to the city of Vienna as a whole.

“Und ist auch faszinierend, dass man so weit aus dem Wiener Becken sehen kann, einfach nur vom 13. Stock, eine öffentlich zugängliche Terrasse. Ist ja schon genial als Bewohner. Man kommt ja mit dem Schlüssel rein. (...) Und dann an manchen Tagen hast du so eine klare Fernsicht, dass du den Schneeberg ganz deutlich vor dir hast.”12 (Informant 13, 12.08.2019)

Through the analysis of the users’ photography and their comments, we see that even though they shared some similar perceptions in relation with the macro level and the Donau City area, they seldom evoke social interactions in the public open spaces. Rarely are social scenes featured in photos of places or elements. Photographs either depict specific elements that behold a story per se or directly relate to the individual. Or, they show design, or architectural elements and landscapes that hold characteristics related to and contrasting the other scales. The only photographs that showed possible scales overlapping between residents and workers evoked the Copa Beach on the waterfront and a fountain located next to the ARES tower (Figure 13 and 14). Other than these 2 places, we could not identify places or situations where these 2 social groups come together or interact. Even so, the social separation is also felt amongst residents depending on the building, hence the community, they relate to.

“Dieser Kubus. Da ist noch Wasser und eine Kugel. Ich finde das ist auch ein Symbol für die Donau City.”14 (Informant 4, 01.07.2019)

“Also das gefällt mir sehr gut. Das ist wirklich wie eine Oase.”16 (Informant 10, 02.06.2019)

Adopting a scalar perspective, allow us to highlight that both groups are aware of each other while not having many connections or social interactions with one another (Figure 15). If this social dynamic among residents and workers is salient in the photovoice corpus, the interactions among residents are also rarely expressed and infrequently observed. One of our informants mentioned his active implication a few years ago in organizing an event that would reach out to the residents and foster a sense of community. However, meagre support from the WED and local authorities have discouraged him over the years. As such, users of Donau City largely perceive the open spaces as transit spaces rather than places of opportunities. They mention for instance the poor design quality, the lack of sitting opportunities or uncomfortable furniture. This perception underlines a space planned and conceived as purely functional without considering the potential for practices and appropriation, in turns revealing the “empty” perception felt while experiencing these spaces. The call for a better socially integrated environment of Donau City’s open public spaces - that would offer more opportunities - was stressed in the interviews: informants asked for better-designed place, outdoor commercial or de-commodified places to sit, linger, meet neighbours or gather.

Conclusion

By using photovoice interview to collect data on users’ daily experience, we aimed at tackling how residents and workers mentally structure their built environment and how that evolving structure might or might not create meanings for them. Paraphrasing Lynch (1988), we looked at how their lived space could be associated with a path, a connection, an edge or a landmark representing the users’ place perceptions. We analyzed the intersection between conceived space and everyday life practices (perceived space) as a means to come up with a dynamic understanding of lived space (Madanipour, 1998). Following this perspective, we were able to understand and explain the material space of Donau City, its social and psychological dimensions and attributes, exemplifying a new build environment set in a public-private partnership. We collected information directly from the users that improves the understanding of the open environment of Donau City and could be valuable to current stakeholders (planners and developers) and policymakers (Wang & Burris, 1997).

Results underlined the lack of social interactions as a silent dimension in the commented pictures. This absence has been manifested through the recurrent feeling of emptiness and materialized through the poor design of open public spaces, in the lack of proper protection against wind and, in comfort zones concentrated around the micro-scale: domestic and working places. As scholarly works have shown, social interactions are determinant for behaviour and well-being in a built environment and can be increased through good planning and thoughtful urban design (Askarizad & Safari, 2020). This means, for instance, in the case of a new build environment such as Donau City, that experiences, uses, practices and appropriations should be better scrutinized and be considered within the urban development process. Although attention to open public spaces is central, in our case, features and experiences around “comfort zones” should be further investigated in order to improve the current open spaces regarded as mere “transit spaces”. These empty open public spaces could become places for the public to avoid the current social fragmentation and to improve public life (Koch & Latham, 2013). Set in a public private partnership, the spatial fragmentation is already effective at the institutional level through multiple land ownerships and is felt in the management and the quality of open spaces. Architectural and urban setting’s fragmentation plays a role in social interaction and cooperation. This fragmentation creates a disruption in the daily routine that can negatively impact the lived space. It is important to understand the workers’ and the residents’ identification to the area in order to improve amenities. This would help undermine the perception of a “functional” environment. Behaviours are affected by the quality of the built environment, which in turn influence the daily and personal life (experience) of users. We could here draw on one scene observed during our fieldwork: one of our informants had set a table with chairs in the open space in front of his shop. This place suddenly became an informal but effective meeting point for the neighbours as well as for workers passing by. People would stop to greet the informant, start chatting, etc. Place attachment and positive space experiences are based on the qualitative dimensions of space and its potential to integrate and interact with other people (Altman & Low, 1992), this is what conceived space should aim at.