1. Introduction

This paper is based on research carried out within a larger international research project1. The research was conducted in two high-rise estates in Switzerland built between the late 1950s and the 1970s - Telli in Aarau, and Tscharnergut in Bern. Although both housing complexes are recognised in architectural historical discourses as pioneering and important built legacies of the post-war construction boom in Switzerland (Huber and Uldry, 2009; Zeller, 1994), among the general public they suffer from a negative reputation (see chapter 2 on context). In Aarau and Bern the estates are often colloquially described by pejorative names such as “the dam walls”, “the rabbit hutches” or even “ghettos” (Althaus, 2018, p. 257; Bäschlin, 1998, p. 197). However, contrary to the widespread and stigmatising stereotypes that go along with these labels, residents generally emphasise the quality of life in the estates and identify highly with their neighbourhoods (cf. ibid.). This discrepancy between negative outside and positive inside views has also been documented for other large-scale estates of the post-war period (cf. Harnack and Stollmann, 2017; Furter & Schoeck, 2013; IBA, 2012). These positive internal perceptions are due to - as the analysis of interviews with residents suggests - both the people who take care of the various collective places and facilities on site (residents, caretakers, housing management); and the important role of community initiatives and community centres for collective issues.

This paper therefore takes a closer look at the community structures in these settings and discusses the questions: Which ideas and planning policies have influenced community building and the construction of community centres in the two estates? How are practices of community building applied by the community centres in these settings - and on which foundations are they based? And how does community building face the challenges and potentials regarding socio-demographic diversification of the neighbourhoods today?

The paper is structured as follows: After an outline of the research approach and methods applied, the two cases are introduced and contextualised within the wider history of large-scale housing estates from the post-war construction boom in Switzerland. The focus then shifts to policies and practices of community building in these settings with regards to the three questions mentioned above.

2. Research approach and methods

To engage in critical reflection on the role of community building in shaping housing estates across time, it is prudent to disentangle the community building objectives inscribed in initial social and physical arrangements from the ways in which actors cope with them in the present. For this purpose, we draw on an anthropology of policy (Shore et al., 2011), by considering policies as regulatory instruments that create or consolidate social, semantic and physical spaces on the one hand, and everyday practices on the other. Analysing policies and practices with regards to community building in the physical and social realm of a large-scale housing estate means looking closely at the ways in which architects, planners, owners and local authorities envision(ed) sociality and its material manifestation in collective spaces on site. In parallel it also requires consideration of the diverse practices of community workers and residents, who promote encounters and social and cultural activities in the neighbourhoods.

In order to capture these different perspectives, the study employs a qualitative, multi-method case study approach to examine each neighbourhood in a context-specific setting, while also assessing generalisations that extend across both neighbourhoods. We used document analysis of policy relevant papers, field observations, mapping and in-depth interviews with various local stakeholders, in order to include a wide range of perspectives and to obtain a rich and nuanced picture of the community structures. Data collection in the two case studies took place between October 2019 and September 2021. In this period, 60 qualitative interviews were conducted with a total of 69 participants, each of whom belongs to one of the following groups of actors who influence or participate in local community life on site: 1) local authorities, 2) property owners and property managers, 3) caretakers, 4) representatives of community centres, neighbourhood associations and local schools, and 5) residents. The sample of residents was selected to maximise the diversity of interviewees in terms of age, gender and country of origin. The interviews were based on interview guides. Furthermore, to include childrens’ perspectives, a film project, letter campaign and photo documentation were carried out with the pupils of local schools. Data analysis largely followed the grounded theory approach, with the simultaneous collection and analysis of data (cf. Corbin & Strauss, 1990). At the time of writing, the research project is in the final phase of data analysis, wrapping up findings for publication. The project will be completed in October 2022.

3. Research context: post-war high-rise estates in Switzerland

In post-war Switzerland, large-scale housing complexes were constructed as a response to a severe lack of affordable housing in relation to the economic boom at the time. From the 1950s through to the oil crisis of 1973, the population of Switzerland grew by 1.3 million people (or 26 %) (BfS, 2014, p. 1), due to increased birth rates and labour migration, especially from Southern and South Eastern European countries. This rapid population growth led to housing shortages, especially in urban and suburban areas where there were more job opportunities, which in turn led to internal migration from rural areas. The quantitative increase of the construction boom was impressive: more than a quarter of the existing buildings in Switzerland were erected in the twenty years that fell between 1950 and 1970 (ibid.) - with increasingly dense and high-rise structures being produced from the mid-1960s until the early 1970s (Koch 1992, 197). Building processes were rationalised and industrialised prefabrication was widely applied, pushed forward by a strong belief in progress and technological innovation at the time. Concurrently, similar developments and the construction of large-scale housing estates were taking place in many other European countries in order to create affordable housing for working and low- to middle- income families (cf. Baldwin Hess et al. 2018). Unlike neighbouring countries, Switzerland was not affected by the destruction of World War II and cities and facilities remained intact. This meant that the new housing developments were primarily concentrated on land available in the outskirts and suburban areas. Due to the Swiss federalist political system, the housing constructions were not driven by overarching government-led policies but by local planning and often by private general contractors (Furter & Schoeck 2013, 11f). Between 1945 and 1974 incomes in Switzerland increased by 230% (Müller, Woitek 2012, 99) - a development which went along with the expansion of the welfare state and prosperity for broad sections of the population. This also led to an increase in living comfort. The newly built apartments in the large-scale housing estates provided modern living standards and were advertised as the ideal living space for the nuclear family and people with modern lifestyles (Althaus 2018, p.101).

With the oil crisis of 1973 and the emerging critical voice of the ecological movement, however, public opinion changed. With the economic recession, 8% of all jobs in Switzerland were cut (Hitz et al. 1995, 52). Many migrant workers from southern and south eastern European countries - who had significantly contributed to the construction of the newly built environment and infrastructure - were sent back to their countries of origin and the population and cities did not grow as predicted. Large-scale housing construction came under fire as a symbol of the failed radicalism of the limitless belief in growth and was subsequently widely and effectively rejected. This rejection continues to affect the public perception and negative reputation of this built heritage up to today (Schnell 2013, p.194; Althaus 2018, p.111). In the 1980s and 1990s, the first construction defects of the buildings, which were often built in a short period of time with partly new building materials, started to become visible and the estates started to lose value. The marginalisation of the estates was partly underlined by the trend towards dwelling in city centres, and by a concentration of low-income migrants’ households among the population (Althaus & Glaser, 2015, p. 246).

Tscharnergut, Bern

Tscharnergut, a 125,000 m2 estate is located in the Western part of Bern, was constructed between 1958 and 1966, and was the first major housing complex in Bern and one of the first in Switzerland. It was built by a collective of seven architects led by Hans & Gret Reinhard. Today, the estate comprises 1182 flats and houses 2600 residents.

The decisive factor for the planning of Tscharnergut was an acute housing shortage, which led to a demand for political action to promote affordable housing on a plot of land in the outskirts, purchased by the city of Bern in 1949. For this, in 1955 the city of Bern leased the site to several non-profit housing companies. The owners consist of two housing cooperatives (FAMBAU, Baugenossenschaft Brünnen-Eichholz), a labour union (Stiftung UNIA) and the pension fund of the City of Bern. Furthermore, a row of low-rise buildings in the middle of the estate belongs to private homeowners. Private ownership was consciously incorporated in order to include higher income families in the estate. From the outset, the City of Bern has been responsible for the upkeep of the school, kindergarten and day-care centre in Tscharnergut along with the green outdoor spaces. The different property owners are tied together through a public company, the Tscharnergut Immobilien AG - TIAG, which is responsible for the construction, maintenance and renewal of all common buildings and facilities of the neighbourhood.

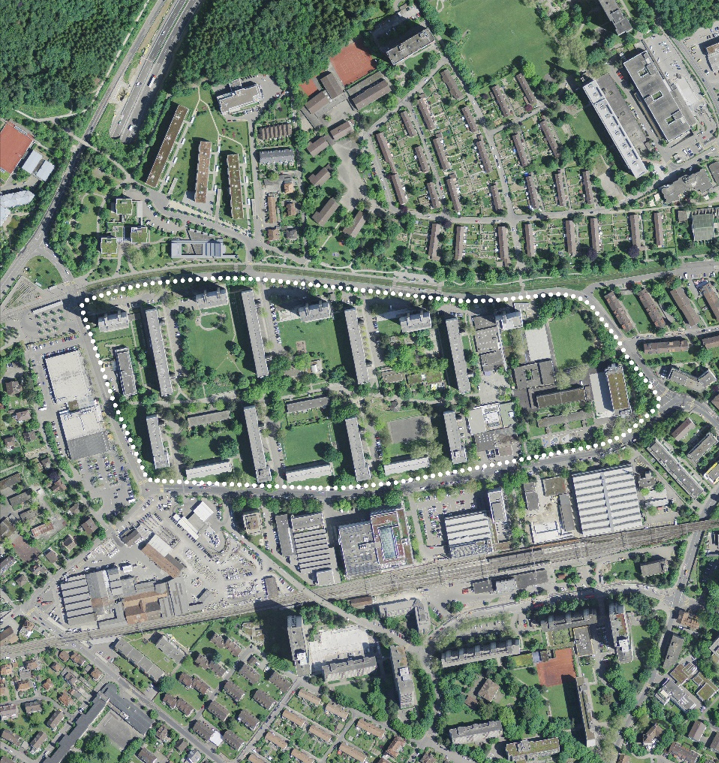

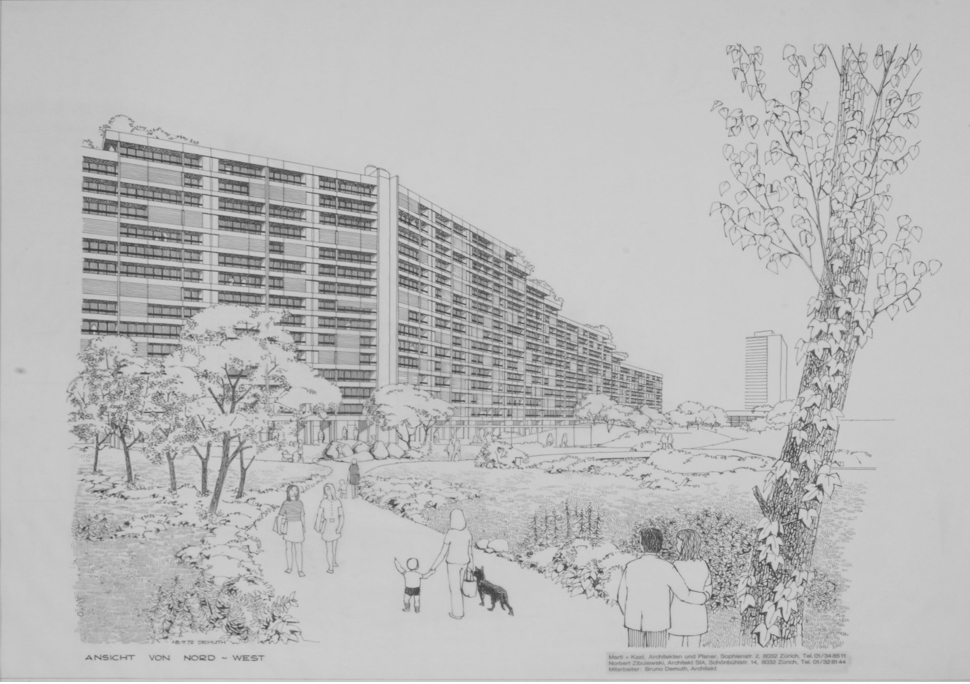

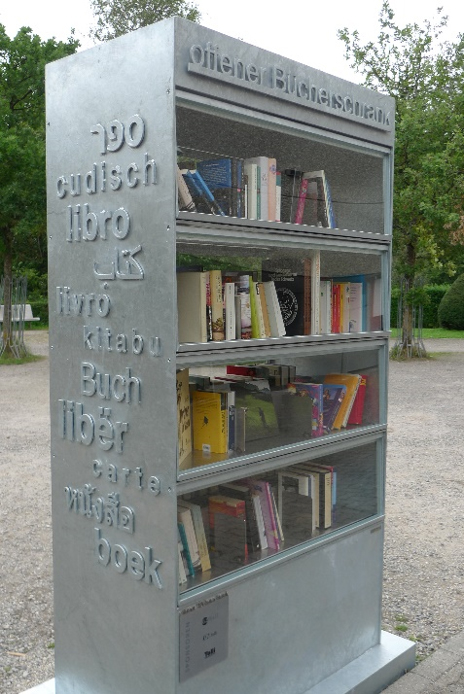

Tscharnergut’s urban design is clearly structured with five high-rise buildings, eight slab-type houses and two rows of single-family houses (figure 1). This mixed construction method, with the alternation of high and low, large and small buildings, was intended to prevent a “monotonous” appearance and, additionally, create large and clearly structured exterior spaces between the residential buildings. The team of architects behind the planning of Tscharnergut had a concept that was unusual in Bern at the time: a dense overall neighbourhood development with a strong social imprint and a community-promoting structure (Steiger, 1963, pp. 7-9). For this, a variety of facilities and collective spaces for playing, meeting, sports and leisure activities have been included in the estate, together also with a little shopping centre, a prominent neighbourhood square and a restaurant (figure 2). The community centre which was planned with the estate, is the first of its kind in Switzerland and played a pioneering role for the formation of future community centres, not only in Bern but also other places in Switzerland, such as Telli in Aarau (figure 3).

© Architekturbibliothek Hochschule Luzern

Source: Figure 2: Tscharnergut comprises a mixture of high-rise buildings and slab houses with large green areas in between

Telli, Aarau

Five years after the completion of Tscharnergut, Telli, one of the largest housing estates in Switzerland, was built in the outskirts of the small town, Aarau. Construction took place in four stages between 1971 and 1991. Telli encompasses four extended high-rise blocks in a green area (figure 4) and is very prominent in the small town, which is characterised by an old city centre and mainly smaller buildings. Today, around 2000 people live in the 1258 flats, constituting around 10% of the city’s entire population. Similar to Tscharnergut, the aim of the developers was not simply to build many affordable flats, but to create an “integrated neighbourhood” with diverse infrastructure and collective spaces, such as a shopping centre with a restaurant, playgrounds and sports fields, as well as a school, a kindergarten and childcare facilities. The construction of Telli’s community centre was also already part of the architectural competition’s criteria and the planning team visited existing community centres in Switzerland (such as those in Tscharnergut and Le Lignon in Geneva) (Althaus, 2018, p. 219).

Telli has a very complex ownership structure. Under the lead of the City of Aarau, initially four land owners organised an architectural competition and worked out a property owners’ contract. The ownership diversified after the general contractor Horta AG - who was one of the land owners and also the developer of the estate - went bankrupt after the oil crisis. The two middle blocks went into the possession of a pension fund of a large insurance company (AXA Winterthur). The first and the last block are owned by several institutional investors, but partially also by the municipality of Aarau (Ortsbürgergemeinde) and a housing cooperative for the elderly. More than a fifth of the flats in the blocks belong to private homeowners. The property owners’ contract regulates the construction, management and maintenance of the common facilities. The owners are responsible for the outside spaces in their parcel of land. In 2006, the City council of Aarau initiated the property owners’ forum “Mittlere Telli” in response to tensions that arose within a neighbourhood development programme. The purpose of the property owners’ forum is to coordinate and negotiate the maintenance and renewal of the common infrastructure and to discuss overarching tasks and interests of the estate. The meetings of the forum take place twice a year and are chaired by the City Mayor of Aarau.

Socio-demographic diversity

Whereas, initially, mainly low to middle income, Swiss and Southern European families moved in the estates, over time the heterogenous socio-demographic composition has continued to diversify (cf. Bäschlin 1998, 207f; Althaus 2018, 226ff). The current population is very international, a reflection of increasing global migration flows into Switzerland. Among the 2000 residents in Telli, there are fifty-five different nationalities, making up 32% of all residents (compared to the city of Aarau’s average of 21%) (Stadt Aarau, 2021). In Tscharnergut, 42% of the 2600 residents do not have a Swiss passport, which is significantly higher than the city of Bern’s average of 24% (Stadt Bern, 2021). Due largely to the occupancy policies, no concentration of a single national, regional or ethnic group can be observed. Furthermore, binational couples and families are widespread, which illustrates that the migrant populations do not exclusively live in separate groups according to their nationality.

Whereas initially the estates were in large part populated by families with children, both estates today have an above-average number of senior citizens, many of whom have lived there for many years. This is particularly striking in Tscharnergut, where nearly 38% of residents are 65 years or older, compared to Bern’s average of 22% (Stadt Bern, 2018), in Telli nearly 29% of residents are over 65, compared to the average of 17% in Aarau (Stadt Aarau, 2021).

4. Policies and practices of community building and the role of community centres

From the beginning up to present day, collective structures and measures to implement community building are part of the estates’ planning and development policies.

Planning policies

Both Telli and Tscharnergut’s urban architecture is rooted in post-war neighbourhood planning ideas, most of those themselves stemming from visions conceived half a century previously. The central concept is the idea of being able to influence social interactions and community life among residents through the physical arrangement of the neighbourhood (Patricios, 2002). Especially influential in the urban planning discourse in the Swiss context of the 1950s and 1960s has been the concept of the structured and dispersed city (“gegliederte und aufgelockerte Stadt” - Göderitz, Rainer and Hoffmann,1957) which - influenced not only by the modernist guiding principles disseminated by CIAM in the 1920s and 1930s but also by earlier ideas of the garden city and housing reformers - proposed a separation and ordering of functions, putting the emphasis on the creation of healthy neighbourhoods for housing (cf. Sulzer, 1989, p. 41 for Tscharnergut; Fuchs & Hanak, 1998, p. 131 for Telli). The structural form of large-scale housing estates has also been influenced by Le Corbusier’s urban planning idea of the Unité d’habitation as a free-standing large-scale form for housing with integrated facilities and surrounded by green space (ibid.; Kraft, 2011, p. 52; Gysi et al. 1988, p.183). Both housing estates have been planned and built as overall neighbourhood developments in the outskirts of the cities with large green spaces between the blocks and with not only the infrastructure needed for daily life but also with various community structures. The entire area of both housing estates is traffic-free and intersected only by pedestrian and bicycle paths.

Planning policies in both developments were based on the goal of building affordable housing for broad sections of the population from lower to middle income households. Over the years Telli expanded their target market to encompass also more expensive flats, whereas Tscharnergut focused on lower-priced flats. This is primarily due to the ownership structure: housing cooperatives and non-profit organisations dominate Tscharnergut, whereas Telli has a mixed, but mainly profit-oriented ownership. Both estates provide mainly rental homes but also allow for some homeownership. In Tscharnergut, about 70% of the flats are 3.5 rooms (two bedrooms), which were intended to be standard family flats. Compared to this, the architects in Telli aimed for a larger variety of sizes of flats to ensure a broad housing supply and social mix, with flats ranging from 1.5 (studio flat with kitchen) to 5.5 (four bedrooms) rooms.

When Tscharnergut and Telli were planned and built, the main emphasis was on the need to create housing for families with children (cf. Bäschlin 2004, p.35f; Althaus, 2018, p.221). This translates most visibly into space through provision of common outdoor facilities, including playgrounds, petting zoos (figure 5), paddling pools, sport and picnic/ barbecue areas which can be found in both estates. Schools and kindergartens are located on site within a short walking distance from the flats, without the children having to cross any streets (figure 6).

Community centres as integral part of neighbourhood planning

The initiative for the community centre in Tscharnergut, the first of its kind in Switzerland, came from the leading architects Gret and Hans Reinhard, who persuaded the responsible authorities and political decision-makers to support the project. The Reinhards were an architect couple who from the 1950s until the 1970s had a decisive influence on the construction of large non-profit/ social housing estates in Bern. Inspired by existing examples in the Netherlands, Sweden and Finland, they were convinced that social/ mass housing with its severe restrictions on apartment size and construction costs had to be compulsorily supplemented with public and semi-public spaces - to balance out the narrowness of the individual apartments and promote community life in the neighbourhood (Bäschlin, 2004, p. 41). Therefore, when the city authorities approached the planners with the demand to use the land more intensively and increase the number of apartments and floors, the architects in return demanded that the city build a community centre. Their main argument for the community structures centred on the importance of creating spaces for leisure activities where people could meet and get to know each other. Ultimately, the architects’ intention was to create acceptance and make it easier for the future population to live in such a large-scale structure - which was a complete novelty in Bern at that time. They were able to convince the city and municipality council (cities’ executive and legislative) to finance this endeavour. When the city council of Bern (executive) approved and finalised the project, it took up the points by the Reinhards and argued in particular with regards to the increased importance of providing structures for “meaningful leisure time” (ibid., 45). This can be understood within the post-war context, which also went along with transformations in the labour market (such as the introduction of shorter working hours and the five-day week in many areas) that led to more time for leisure (figure 8).

In Telli, which was planned ten years later and based on Tscharnergut’s experiences, the initiative came from the four initial property owners. In 1969 the municipal assembly (meetings in which all citizens decide on local political initiatives) agreed to change the zone plan accordingly in order to enable the construction. During the planning process, a group of five sponsors emerged to fund the community centre: two institutional land owners, the city and municipality of Aarau and the reformed and catholic churches. The parishes played an important role in the construction and financing of the community centre in Telli - as they consciously decided not to build new churches but rather join forces ecumenically and use a common and neutral location for social activities in the newly built heterogenous neighbourhood (Besmer and Bischofberger 2012, 12).

In Telli, the developers referred more explicitly to possible or presumed negative outcomes of mass housing, which made community structures imperative in their view. At the construction ceremony of the community centre the representative property owner and developer from Horta AG reinforced this attitude, stating: “According to experience, life in such large housing structures takes place in isolated anonymity and ends in loneliness. It is necessary to counteract this unsatisfactory state of affairs, to promote interpersonal relationships and contacts, to bring people of all generations together across religious, economic and political barriers, to bring them joy and to shape their leisure time in a meaningful and educational way. This is the objective for the creation of this community centre” (quoted from Besmer & Bischofberger, 2012, p.13). In short, a negative outcome of the newly built superstructures - especially with regards to anonymity and loneliness - was to be countered by the governance of community through recreational facilities (Althaus, 2018, p.413).

Both community centres offer rooms for communal use and have multi-purpose, leisure and meeting rooms, a disco and a café. Tscharnergut was planned with a crafts and wood workshop, a sports hall and a library, Telli with a communal kitchen and the Swiss version of a bowling hall (Kegelbahn). From the first days up to present day, the community centres have been led by professional community workers who are in charge of running the centres but also of building and strengthening neighbourhood networks. Community work in general is directed to create and strengthen social relations and empower individuals and groups of people to get involved, help each other or effect change in a neighbourhood (Kelly & Sewell, 1988).

From promoting meaningful leisure activities to enabling local initiatives

At the beginning of the last century sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies stated that “community”, in contrast to “society”, is characterised by social cohesion, and associated it with the rural life and interdependence of a pre-industrial village (Tönnies, 1912, p. 17). This concept is still influential today, as community is generally equated with social interconnectedness, solidarity, conviviality and knowledge of each other on a smaller scale (cf. Ciemiega, 2021). Community building policies in both estates have been based on these theoretically founded normative idea(l)s. To this effect, the community centre Tscharnergut was initially charged by the cities’ authorities to also take on an “educational” role, highlighting the importance of creating “meaningful” leisure activities. Giving space to mutual support among residents (e.g. for childcare), to handicrafts and repair workshops, to reading (library) and various further training opportunities (such as language courses), along with meetings of clubs and associations, was intended to counteract “questionable” behaviour (such as watching too much TV, which in the (early) 1960s was a novelty in many households) and to involve residents in "valuable" activities (Bäschlin, 2004, p. 45).

The Tscharnergut centre was built up and led for more than two decades by a pioneering manager who pursued a progressive approach of community work, which he himself had experienced in the Netherlands. This approach focused on supporting and empowering residents to actively implement their own concerns and projects. In this, for him the promotion of encounters and the creation of a good atmosphere were key, along with public relations work to counter negative images of the estate in a citywide context (cf. Uehlinger, 2011, p. 113). A collaborator of his remembers in the interview for this study: “He distinguished himself until his old age by his openness, he was very solution-oriented. Once in the 1970s for example there was a situation in which many older people complained about the noise from youth discos organised by youngsters in the community centre. He suggested that a part of the proceeds from the parties went towards discounted train tickets for Tscharnergut residents. The complaints then disappeared within a very short time” (Interview OW, 02.12.2020).

From the early years onwards, office help, social work trainees and many volunteers were included on the team to support and organise the manifold activities that emerged. Some of the Tscharnergut centre’s activities have been there for decades and continue to exist, with examples including the wood workshop (with open workplaces for a broad public and sheltered employment) or the café with meals for lunch. Other activities are project-based and change over time. In these regards, community work in Tscharnergut is still dedicated to the initial approach “to help people to help themselves” by encouraging and supporting local initiatives from residents. In 2020 for example, a project for neighbourhood help for older tamil people in Tscharnergut was been initiated by a resident. She states: “Older people often need support, especially the ones whose family members live in Sri Lanka or other countries. I was able to get this project off the ground thanks to the support of the community centre” (interview NM, 15.03.2021). As the current director of the community centre states in the interview: “Participation and collaboration are key. People have to have the feeling that they have a say and are invited to do and move things. The most important thing is that residents perceive this as their centre in which they can realise their ideas - that’s why it is so changeable” (Interview OW, 02.12.2020). In addition to the freedom of agency and the joy of experimentation, this requires flexibility, openness, social skills and the acceptance that not every project will succeed or be long term. What is offered is always highly dependent on the demand as well as the emergence of local initiatives and the commitment of individual people.

The educational approach has, also from the point of view of the cities’ authorities, increasingly shifted to an enabling approach by putting accessibility and participation at the top of the list. A city representative states: “One of our legislative goals is to be a city of participation and to consistently promote citizens’ participation in public spaces as well as request it in urban planning and site developments. (…) Community organisations such as in Tscharnergut play a crucial role in these regards also because they are used to work with this approach for decades and have a strong local networking effect between very different people and stakeholders” (from focus group with representatives from social planning and housing administration of Bern, 19.03.2021).

© Archiv Quartierzentrum Tscharnergut

Source: Figure 5: Petting zoo in Tscharnergut, an example of the variety of collective spaces integrated into the housing estates

Promoting participation and working with volunteers

The community centre in the Telli estate was conceptualised in a similar fashion to the one in Tscharnergut. As in Tscharnergut, the community centre Telli is dedicated to community work, coordinating and organising, with the help of voluntary residents, a neighbourhood help network; leisure activities; as well as markets (figure 10) and events on site. Furthermore, the community centre runs a recreational meeting and leisure place for children, operates the mini-golf course, holds regular meeting events and organises a home meal service for older residents (figure 7=.

As in Tscharnergut, the majority of projects are volunteer based. Community building activities depend on residents who use and participate in them, or who set up and organise activities in their spare time. Finding volunteers however is challenging; in interviews, old residents recall that housewives played a crucial role in establishing community life and performing voluntary work in the early years of the estates. Women today tend to be engaged and busy in paid employment and in household and family duties, have less time for volunteering. Community work also has to adapt to the fact that few people today want to commit to long-term engagements and instead welcome short and flexible volunteer assignments. “The responses to many calls for participation for which one has to commit, are very small. Reliability is a big issue. Many want to participate but then don't have the stamina” (Interview HT, responsible for neighbourhood association Telli, 19.07.2021). Nonetheless, the community building activities continue to work mainly on a volunteer basis and currently still find people for longer-term commitments - many of whom are retired. The community centre in Telli, for example, currently relies on a pool of about 50 volunteers (Interview AF, director community centre Telli, 17.03.21). An older resident who moved to Telli with her partner two years ago reports: “If you are new, there are many ways and it is easy to get involved through the community centre. You can participate, but you don’t have to. They are always happy to have volunteers. I am active in delivering meals for the home meal service and through that I’ve got to know so many people in the neighbourhood” (Interview AS 07.05.20). Similar positive attitudes can be observed in the interviews with residents in both estates. For some, the community structures are more important, which is especially the case for older people and families, which are also the main target groups of the centres (see chapter 4). For others however - especially for working persons without children and for younger adults - the community centres are often quite far away from their everyday realities and many of them never or hardly ever visit them. Neither in Telli nor in Tscharnergut did anyone question their raison d’être during the interviews.

© Archive QZ Tscharnergut

Source: Figure 7: The community centre in Tscharnergut has been key in promoting social encounters since the very beginning

Importance of professional structures and financial models

The type and intensity of community work depends not only on the institutional mandate, but also on the professional background and scope of the responsible director of the community centre. Management has changed in Telli five times since its opening in 1974, whereas there has only been one change in Tscharnergut since the early 1960s. Community work and participation was a leading working principle for the first director in Telli (in the 1970s) and the two most recent directors (since the mid-2000s). In the interim period there was a time when the community centre solely focused on the management and renting out of the rooms and communal spaces (Besmer & Bischofberger, 2012, p. 40). In both estates, leadership of the community centres comes with a powerful position in the social interrelations of the neighbourhood. The directors, as key figures, play an important role in linking networks and people - and by doing so also get things moving (or not). A change in this position is therefore always a critical moment as it is highly dependent on the personality, awareness and leadership practices applied. No less important are the staff members, who are key to laterally influencing the functioning of the centres.

To make the operation of a community centre successful, financing needs to be assured on a longer-term basis. Both community centres are (since the beginning) partly financed by the two cities (in Telli also by the Reformed and Catholic Churches) within the framework of multi-year service contracts which guarantee employees’ salaries. However, this funding is not enough for the operation of the centres and is not set in stone. The community centres must also regularly demonstrate their performance and, in case of political change, are at risk of being affected by public austerity measures. Therefore, independent income from room rentals and the above-mentioned activities are also crucial sources of funding. In Tscharnergut, a central achievement was the “tenant franc”, introduced with the first occupancy of tenants, where one franc of the monthly rent from each flat went directly to the community centre via the property management companies. This contribution still remains, although it has risen to 5 francs per household per month. In return, residents can rent rooms in the centre for half the standard price.

Importance of relations with property owners

The community centres are not directly funded by the property owners of the estates and therefore also don’t have a mandate from them. However, in order to be able to maintain community structures in the long term, it is essential that community organisations and property owners’ representatives talk to and respect each other. The directors of both community centres are in regular contact with the property owners’ associations and advocate for social and community-related issues of the estates: in Telli as a participant member of the property owners’ forum meetings, in Tscharnergut in informal meetings but also for an annual walk through the estate, organised by the property owners’ company TIAG. In both cases, participants provide information and discuss necessary measures for the maintenance and renewal of the common infrastructure and buildings. As the director of the Tscharnergut community centre explains: “It took many years of relationship work before we were invited and allowed to have our say. Good contact with the owners is crucial, because that way we can also inform them about planned events and projects and ask for support for collective concerns where it is needed (...) they are usually generous and uncomplicated. Especially in the last year, when we had major financial shortfalls due to Covid 19, TIAG approached us on their own initiative and accommodated us financially" (Interview OW, 02.12.2020). In Tscharnergut, the situation is facilitated by the fact that the owners are non-profit oriented building societies and share similar values. The head of TIAG states: “When people have new ideas or wishes for the estate, they usually go to the community centre. Once a month, I meet with the centre’s director for lunch and then take up such points. Community work also tackles social problems as far as it can and is allowed to. This also helps us” (Interview PA, 20.04.20). If this key figure were to have short-term profit for shareholders as its main goal and lacked understanding for social issues or failed to facilitate communications between the social and real estate sides, the situation for the community structures in the estate would probably be very difficult.

5. Potentials and challenges of community building in diverse neighbourhoods

As immigration has increased into Switzerland, long-term residents have aged and lifestyles have diversified. This means that community building, as it was conceptualised initially, is faced with new opportunities and challenges. In today’s postmodern society, community building has to take into consideration the fluid and porous nature of group membership (Delanty, 2018) and hence also recognise that communities rarely exist as singular entities but are interwoven or intersecting and are characterised by different kinds of relations at the same time, be they lifestyle or interest-based, grounded in particular places, diasporic, activist or other (James, 2006; James et al., 2012).

The interview analysis reveals that the estates’ key community actors mainly consider migration-related diversity an enrichment and in interviews most residents also highlight the horizon-expanding qualities of living among people from a variety of different backgrounds. To some extent, the “multiculturality” is part of the self-image of the residents and is often highlighted as a positive distinguishing feature of the housing estate. However, especially among some older long-term residents who for many years were not used to having neighbours from completely other cultural backgrounds, prejudices, especially against people with other phenotypes or who originate from the global South, prevail. This, however can’t be generalised for the whole age group, as interview material reveals that many older residents also have open attitudes towards migration-related diversity.

Community building within recognition struggles of post-migrant neighbourhoods

Community building measures in these settings therefore always take place in social networks in which there are tensions that must be dealt with, as some actors show openness to diversity and people with migration biographies - and others reject these values, often also incited by right-wing populist political currents in society (in contradiction to internationally oriented currents).

These tensions can also be seen as part of local recognition struggles in a “post-migrant” neighbourhood. The concept of “post-migrant societies” has been widely discussed in new critical migration research and refers to a situation after migration, not only for the migrants themselves, but also for the negotiation process in society. This not only comes with claims for participation and equal rights for migrants, but also with acknowledging migration as a reality in which people with migration biographies constitute part of society and the public sphere (see e.g. Foroutan, 2019; Yildiz, 2015). With regards to post-migrant neighbourhoods of post-war large-scale housing estates, these public spheres manifest themselves in very different ways, whether by emphasising, producing or problematising differences, or by bridging them and acknowledging inclusion and commonality within or despite of diversity (Althaus, 2018, p. 414).

In both of the two high-rise estates, the community centres partly address the migration-related diversity of the population with the aim to either support self-organised migrant networks or to overcome stereotypes and bring people from different backgrounds closer together. For example, for several years the community centre at Telli organised “tandems” in which newcomers were welcomed in their mother tongue by long-time residents. Furthermore, community work advocated for equal representation of migrants in the neighbourhood association and has played a decisive role in changing the annual neighbourhood festival from a “traditional Swiss” programme into an event that celebrates diversity. Both community centres also rent out their rooms to migrants or diverse groups and support cultural initiatives. In Tscharnergut, the community centre has been involved in a number of overarching integration projects in the larger district and just last year decided to offer rooms to a young activist group that is advocating for the rights and inclusion of migrants with no legal residence status in Bern.

Celebrating diversity with essentialist views of “other cultures”

In most community building measures migration-related diversity is addressed regarding the idea of giving space and representation opportunities to “different cultural groups”. As an example, the head of the neighbourhood association Telli who co-organises the cultural festival in Telli explains: “What really works well at the festival are the market stalls of the cultures, where groups of the same cultural background make and sell their food - Tamil, Thai, Vietnamese, Ecuadorian, Bolivian, Mexican, Kurdish, etc. The groups like to come and it’s a great atmosphere. But there are some Swiss people who grumble und say ‘I just want my French fries - why don’t you have these?’. I then tell them that they should try something different. Some do it and others complain or insult us. But we have been resistant to this narrow-minded criticism for years” (Interview HT, 19.07.2021). In this example, community building measures that open up for “other cultures” do so in confrontation with people in the neighbourhoods who reject cultural diversity. However, the community workers often don’t question that by celebrating the peculiarities of a supposed “original culture” for consumption, they also view these cultures in an essentialist and one-sided way.

This view is in part also supported by the demands of migrants’ groups regarding the use and rental of rooms of the community structures, as this interview excerpt of a responsible from the community centre Tscharnergut illustrates: “The cultural groups come to our centre in waves. At the moment Tamil groups are often here, preparing for their new years’ festivities in February. And at the moment there is also a group of young Eritrean men who meet daily at the centre. For a while we had a Turkish group who wanted their own room to celebrate their traditions, but after a while they have disbanded due to low demand” (Interview BS, 02.12.2020).

Interviews and projects with children from the neighbourhoods’ schools reveal that for younger people and children that grow up in the housing estates, migration-specific diversity is a social reality, towards which they have a very light-hearted approach. The film project, in which we accompanied a school class of 10 to 12-year olds once a week for 2,5 months, exploring their neighbourhood from different angles, shows that migration-related diversity is also the norm within many family structures - a norm that the kids do not problematise and in which they also stand confidently2. In conversations most children highlighted that they are aware of and appreciate the migration-related diversity in their neighbourhood but that they would not like to be addressed in particular with regards to their or their parents’ origins but rather just as what they are, kids like all others. In these regards, their narratives are far away from the essentialist attributions described above.

Adapting to needs and socio-demographic changes

According to their mandate, community work in both estates is required to create socio-cultural programmes that appeal to as many residents as possible. In both community centres, most activities are either aimed at broad sections of the population regardless of a person’s origin or they are aimed at specific target groups. Two groups - families with children and older people - stand out in particular, since people in both of these life phases tend to spend quite a lot of time in their living environment and can benefit from supportive neighbourhood networks. The prioritisation of activities of the community centres for these groups has, however, also adapted to socio-demographic changes over time.

In the early 1960s, housing in Tscharnergut was primarily offered to families with children. When the children became teenagers, a number of recreational activities and meeting places for young people were introduced (Bäschlin, 2004). While most of the children from these initial families left the estate many years ago, their parents have largely remained. This demographic ageing - with two out of five residents being over 65 years old - is also reflected in the community centre’s current activities, with a strong focus on older people with events such as “senior dance” and card game evenings. Various activities for families are often project-based or on an annually recurring basis. In Telli, which over the years has undergone a greater fluctuation of residents (Althaus 2018, p.226), population ageing can also be observed, albeit on a less pronounced scale. Apart from various programmes for the elderly, the Telli community centre has therefore a stronger focus on families, supporting foreign-speaking and working parents with activities such as running a children’s club in the afternoons, pre-school childcare, and introducing toddlers to German language and Swiss German dialect through play.

In both estates, community work over the years has adapted - and is constantly adapting - to people’s changing needs in the neighbourhoods. The importance and effects of this flexibility and openness to change can also be observed in the current Covid-19 pandemic, in which cultural activities and direct (physical) social encounters in public have been impeded for months. Between March 2020 and May 2021 both community centres had to partially close (and twice completely), which resulted in a sharp decline in the number of visitors and income. Thanks to the existing service contracts, the employees did not lose their jobs.

At the same time, initiatives of mutual support among neighbours emerged during the crisis. In Telli and Tscharnergut, the already existing longstanding neighbourhood networks and especially the activities of community work have turned out to be key in organising and coordinating neighbourhood help during the pandemic lockdowns, and have provided shopping assistance and home meal delivery services by younger adults for older residents. The trust that has been built up over many years, and the fact that there is a reliable contact point in the neighbourhood with key people who residents know personally, was decisive in ensuring that this offer was also actively used by many older adults. The Tscharnergut’s coordination hub for neighbourhood help has also been profiled in newspapers as exemplary, especially because of its accessibility for risk groups who are not digitally savvy, providing the option of analogue access to help via a phone number and on-site presence (e.g. Streit, 2020).

6. Conclusion

From the beginning up to the present, community building measures and facilities are part of the planning and development policies of the two housing complexes, evidenced by the community centres and the fact that community workers have been employed since the occupation of the first flats. Both community centres have been pioneers in their urban contexts. They owe their existence to their mandate to counter possible or presumed risks of anonymity, isolation and social problems of mass housing with the creation of lively neighbourhoods (figure 9). Community building therefore also grew up with specific values and norms, which continue to exist today, equating community with social cohesion, interconnectedness and solidarity. This understanding was also based on conceptualisations, broadly accepted in urban planning and sociology at the time, that new large-scale urban structures had to be designed as neighbourhoods with community structures.

Community building in Tscharnergut and Telli was initially propagated through a top-down approach by planners and authorities. However, the community centres do not operate solely from a top-down approach, as in both cases the guiding principles of community work is based on the idea of empowerment, encouraging and including residents for bottom-up participation. Therefore, in practice, community building measures at the centres work in a double-loop way, alternating top-down and bottom-up moments. Top-down with regards to offers and services they provide to the neighbourhoods and bottom-up with regards to encouraging and letting people realise their own ideas and projects. The intention of this approach has always been to let a lively neighbourhood life evolve and to provide attractive options for leisure and conviviality, initially with an educational, and subsequently with a more enabling approach.

Learning to deal with diversity

A main driver of community work has always been to establish relations and enable people to get to know and help each other. This has been challenged with growing diversity and socio-demographic changes. Moving away from the idea of a community as a singular unity and acknowledging the dynamic, fluid or porous character of a multitude of local coexisting, overlapping and interconnected communities or sociospheres, would require the community centres to learn and adapt their programmes and services accordingly.

In practice, the community centres often are not at this point, yet. With regards to migration-related diversity it can be observed that the approaches of community work often highlight the “multicultural” character of the neighbourhoods and implicitly go along with essentialist understandings of “other cultures” (e.g. by focusing on the gastronomic delicacies or specific dances of these “other cultures”). As such, they are aimed less at the transcultural experiences and practices of people with migration biographies in the estates but rather contribute to (re-)producing and reinforcing cultural differences. In our view, community work could greatly profit from moving beyond such essentialist cultural ideas, and fully acknowledging the complexity of post-migrant realities and the diversity within migrant communities. The practices of community work, however, can also be understood within the broader framework of tensions that go along with struggles for acknowledgment in post-migrant societies, standing up against voices and populist movements who reject migration-related diversity in general. At the same time, it is also crucial that community building is aware of social inequalities and the importance of language and language-barriers by making access as low-threshold and simple as possible.

Different and similar experiences

In comparing Tscharnergut und Telli, it becomes clear that not all experiences of Swiss post-war large-scale housing estates are the same. It becomes evident, for instance, that the housing and ownership mix influences community building. Tscharnergut has a high proportion of long-term residents and an ageing population, due to the high volume of 3.5 room flats and very low rent, while Telli has a more diverse resident population in terms of income structure, including home ownership, as well as a larger generational mix with the availability of more large flats. Community work in both cases is adapting to these socio-demographic realities. For example, by moving from a main focus on children and young people to older adults in Tscharnergut, or by supporting foreign-speaking families and including older people in various projects in Telli.

Importance of key persons and material conditions

The presence and personality of community workers are crucial establishing trust and motivating volunteers to get involved, making it attractive to them by creating light-hearted and positive experiences. Especially in contexts in which network-building can be demanding, this requires people that have the social skills, dedication and solution-oriented thinking to establish relations, and to moderate in case of difficulties or conflicts. Key people are needed who take on a position of advocacy for the estates in a citywide context (towards authorities and in public relations), but also to take a position for social and community issues vis-à-vis the property owners, emphasising the importance of maintenance and care of the shared and community spaces.

Community building in this sense requires not only the material and financial conditions to strive and collective spaces and facilities, but also professional structures such as community centres with secure and broadly-based financing, ideally combining public service contracts from cities with user generated income in order to assure a long-term success. In times of austerity policies, social and community related issues are vulnerable to cost-cutting measures. The community centres in both estates have not suffered from any public financial cuts (yet) and also thanks to the support of their sponsorships survived the financial losses resulting from the closures during the Covid-19 crisis. This supportive attitude depends on door-opening people in power positions, too. With political changes and changes of positions, circumstances might also change in future.

Today, city authorities and property owners in Telli and Tscharnergut recognise that the long-term commitment of the community centres creates considerable added value to the neighbourhoods and the properties. In interviews they point out the community centres’ importance especially with regard to challenges of the neighbourhoods resulting from demographic ageing and the migration-related diversity - and the potential that lies in the participatory approaches of community building (which they also more and more value or start to include in their agendas). As long as this support is there, community centres work and will continue to do so. By acknowledging/ learning to deal with and/ or “normalising” diversity, they can contribute to making neighbourhoods more inclusive, without (too much) social control and constrictions.