A matter of context

Comics always had a robust and specific presence in the French cultural scene. Not only in terms of popular culture but the entire social and intellectual context. It was precisely in this country that the medium paved its way into academia, in the early 1960s, with the emergence of the first groups devoted to the study and criticism of bande dessinée. At the same time, Charles De Gaulle would say: “Really, you know, my only international rival is Tintin! We’re both little fellows who won’t be got at by the big fellows. Nobody notices, because of my height!”, a statement revealed by André Malraux (1971), then Minister of Culture and a self-declared fan of Hergé’s work. The General was assuming the role of French counterpart of the Belgian reporter, or perhaps comparing to the real gaulois, Asterix, equally short, brave, and resistant to foreign invasions, a more suitable metaphor. Indeed, De Gaulle’s Minister of Youth Affairs and Sport, François Missoffe, once told Goscinny that, during a cabinet meeting in 1968, the General gave each of his ministers the name of a character from the Gallic village (Didier Pasamonik, 2009). Conceived in 1959 by Goscinny and Uderzo at the latter’s apartment in an HLM social housing estate in Bobigny (Pajon, 2015, p.111), Asterix rapidly acquired a major relevance in the country, giving the name to the first French artificial satellite, launched in 1965. While the adoption of Tintin by France also reached the Chamber of the French National Assembly, debating whether the Belgian character was left-wing or right-wing by its 70th anniversary in 1999. But the interest of French intelligentsia with comics went way beyond major bande dessinée characters like Tintin and Asterix, as might prove and the fact that Roland Barthes once qualified Claire Bretécher, the famous cartoonist of Le Nouvel Observateur and one of the founders of L’Echo des Savanes, as the “best sociologist of the year” in 1976 (Parone, 1977). More than any other western country, these accounts testify to France’s recognition of the legitimacy of comics at the level of official culture and of its role as a barometer of its society.

In addition to comics, France is also a country known for segregation and the crisis of the banlieues. A country where the social problems of the 19th century became the urban issues of the 20th century due to the clear territorial expression that they progressively acquired, particularly in the outskirts of major cities. (Machado e Moura, 2006) Although this phenomenon has been especially evident since the late 1980s, it started long before with Baron Haussmann’s gentrification of Paris, which relocated the working classes from the centre to the suburbs. This segregation played a significant role in the Paris Commune, originating the so-called “revenge of the exiles” (Donzelot, 2006, pp.38, 102). Somewhat ironically, as Bernard Marchand (1993) puts it:

Victorian England, so attached to all forms of segregation and which had almost institutionalised inequality, knew how to avoid translating it too brutally into the urban space, whereas France, which claimed to be more egalitarian, especially under the Third Republic, gave birth around its capital to one of the first great social ghettos in urban history.

However, it was in the economic boom of the post-war era, during the so-called Trente Glorieuses, the three-decade period of economic growth and prosperity from the end of the Second World War to the oil crisis of 1973, that the country implemented a technocratic strategy of “modernisation of society through the urban” (Oblet, 2005, p.87). A proactive policy based on the construction industry and the diffusion of concrete prefabrication, benefitting the Public Works sector. The State carried out the massive construction of large residential estates - called grands ensembles, whenever above a particular dimension - in major cities’ crowns. Composed of bars and towers, these complexes mostly of social housing - in French HLM, for habitation à loyer modéré - were built during two decades, between the 1953 Plan Courant and the circular Guichard, which put a term to it in 1973 (Dufaux, Fourcaut, 2004, pp.15-16), at the rate of 300,000 apartments per year in the 1960s and 450,000 in the early 1970s. A boom that matched the country’s lack of housing and welcomed the rural exodus and immigration from Southern Europe and North Africa needed to respond to France’s new industrial priorities quickly. Especially the Algerians, who had been given priority of entry in the country because of a tacit assumption that they would return to their homeland after Algeria’s independence in 1962, something that didn’t happen (Ross, 1995, pp.152-153).

Initially, these new neighbourhoods had some social and ethnic mix - mixité - primarily due to their attractive power compared to the city centres’ lack of hygiene and comfort. But, soon, the middle classes, followed closely by the white working class, as soon as their saving allowed them, opted for a peri-urban adventure, seeking comfort in a family house with a garden, without the company of the poorer. So, these schemes were progressively relegated to the most disadvantaged populations, without resources for accessing the property and for whom social housing represents the final step of their residential trajectory (Donzelot, 2006). Finally, in the 1980s, these neighbourhoods faced a deep crisis, becoming subject to social segregation and the harsh reality that sociologist Pierre Bourdieu compiled in La Misère du Monde (1993). This public policy and this urban form were doomed by the entire society and the media, leading Le Monde to publish the headline “Raser les grands ensembles?” - to raze the large housing estates - as soon as 1982 (Dufaux, Fourcaut, 2004, p.40). No systematic demolitions occurred, but the State outlined several politiques de la ville. These included renewal processes with many partial demolitions and reconstructions to mitigate these effects and, sometimes, foster gentrification under the guise of social mixité. As a result, numerous neighbourhoods are now ghettos, places of social exclusion, stages of urban violence and images of the profoundly anti-urban feeling that runs across French society. Sites of low reputation, which even compose their proper vocabulary - la zone, loubard, galère, racaille, etc. - are often subject to security measures, as reinforced as the concrete that made them.

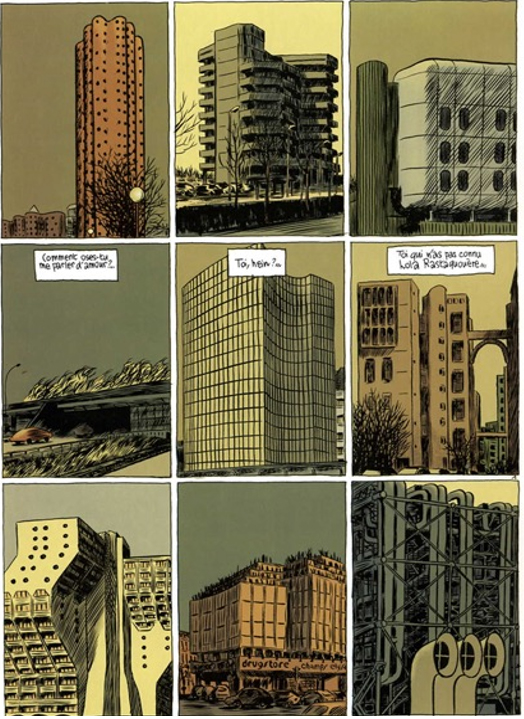

This article inquires on the visions that French bande dessinée has provided of the broadly stigmatised and mediatised space that corresponds to its urban outskirts, particularly the social housing estates organised in grands ensembles and cités HLM, from the 1970s until today. What depictions can we find in the ninth art and its images of our world of representations about these spaces? What different perspectives and social questions do these comics illustrate? (figure 1)

2. Representations in comic strip form

As a form of literature, Comics generally tend to focus mainly on a given narrative, thus often diluting spatial aspects within a series of human and social ones. Although there are many exceptions to this assertion - with series like Les Cités Obscures that bring architectural and urban features to the foreground -, the characterisation of the physical realm, required to frame the narrative and inevitable given the medium’s graphic dimension, tends to subordinate itself to the story’s development, often by simplifying the drawing - which might suggest more than it describes -, and giving priority to the action. Moreover, the mechanical properties of the medium, which narrates through sequential panels, decomposes the architectural space in partial visions, allowing the whole to be reconstructed only in the mind of the reader. It is only at precise moments - like aerial or distant views - that one realises, with more information, the urban form at stake:

A contemporary comic book reader almost naturally identifies what is “urban” in it: the asphalt, the cobblestones of its streets, the stone, the brick of its walls, the glass and the steel of its buildings (...) [there is] a decor that makes the contemporary reader recognise himself and know that he is “in town”. However, this presence of the city serves as a background; it does not appear as an explicit subject of comics. The restricted space of the panel encloses the viewer in closed areas where urban existence is obvious but unquestioned evidence. To open the gaze and for the city to become an object of representation, it is necessary to meet the points of view where it opens in perspectives, in the squares or the main avenues. Above all, the city ceases to be evident when I enter or leave it. (Garric, 2014)

Although this feature is likely to occur in the rendition of any urban experience and not only in comics, each medium - from cinema to painting or literature - proposes a different approach, manipulating and composing its own ‘construction by images’. Borrowing the title of English pop artist Richard Hamilton’s 1956 work “Just what is it that makes today’s home’s so different, so appealing?”, one could ask where lies the seductive power of these mass housing representations? Hamilton’s collage vividly portrays the paradoxical nature of the modern notion of home simultaneously as a multi-media recipient and a mediated construction, both an object of desire and its avid consumer. Similarly, by confronting the ambiguity of images and representations with the complex realities of mass housing living, one realises the multitude and richness of the different approaches, both in comics and in cinema.

The examples of comic books that we analyse further clearly reveal the qualities and the contradictions of comic strips that explore the urban context of the banlieue and its architectural forms, either when narrating its dystopic and violent environments or when enhancing the anthropological and visual qualities of these suburban settings. Complementarily, a quick overview of French movies on grands ensembles, from Malik Chabane’s Hexagone (1994) - in English: Tale of the Suburbs -, to Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995) - in English: Hate -, Rabah Ameur-Zaïmeche’s Wesh wesh, qu’est-ce qui se passe? (2001) - in English: Wesh, wesh, what’s happening? - or, more recently, to Leïla Sy and Kery James’ Banlieusards (2019) - in English: Street Flow - or Ladj Ly Les Misérables (2019), would reveal an equally exciting and diverse set of approaches. Some of these films are actual products of the suburbs, all are mediated constructions of varied genres, from documentary to comedy and drama, and all are triggers of different readings of the reality they portray.

French sociologist Isabelle Papieau argues that when they are “called to constitute a comic book theme, the images of the suburbs will demonstrate a strong ‘symbolic power’ and draw ’a bridge’ between the fictional domain and the universe that is ours.” (Papieau, 2001, p. 15). It is perhaps in this specific ability of comics of establishing a link between reality and fiction that lies the seductive power of the medium. Unlike cinema, a bridge mediated by the graphical expression of the drawing and the organisation of a sequence in multiple juxtaposed panels, as well as by the reader’s own rhythm.

3. A diversified corpus

The relationship between architecture and comics has been discussed in many exhibitions and publications, especially since the Institut Français d’Architecture organised the exhibition Attention Travaux! Architectures de Bande dessinée in 1985, which itinerated through various European institutions, including the CAM/Centre of Modern Art at the Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon. Curated by Lionel Guyon, François Mutturer and Vincent Lunel for the broadcast department of the Institut Français d’Architecture, directed by François Chaslin, it groups a collection of images by different topics. Three of which fit within our scope: Vérités de la palissade, H.L.M. and Banlieue. Forty panels, primarily black and white, reveal collective housing schemes, in the modern language of postwar architecture, and unqualified open spaces at night, hoardings, terrains vagues, vandalised telephone booths, piled scrap cars, or parked in extensive lots next to the buildings. At first glimpse, the criticism of the monotony of these places and their lack of quality and maintenance is implicit.

However, many of these images are extracted from comic books whose stories are marginal to these places, sometimes having little, if anything, to do with them. Indeed, quite often, the curators of the exhibition selected the only panel of the entire story that depicts these neighbourhoods (Boucq, 1984, p.39; Filippini, 1984, p.10), and the exhibition catalogue reproduces these drawings without offering any comment (Guyon, Mutturer, Lunel, 1986, pp.67-70); the merit of the exhibition lies precisely in providing a collection of drawings, not in formulating their criticism. Yet, the comic magazine A Suivre devoted a special issue to the exhibition, for which several authors specifically drew comic pages. Walthéry (Busscher, 1985, pp.34-35) brought the short story of a couple of young teenagers while looking for a place for some intimacy in the basement of one of these buildings, discover the skeleton of the architect who got lost in the endless spaces he had designed without being able to find his way out. The story conveys explicit criticism of this dehumanised architecture with humour and funny graphism.

At the same time, Attention Travaux was opening in Angoulême, a special issue of another magazine, Urbanisme, devoted to the inter-ministerial programme Banlieues 89, offered a quick overview of the renderings of housing complexes in comics, as in literature and painting. In the introduction, Gilles Rousseau (1985, p.77) remarks that “contemporary comics (…) set up a suburban setting that is not yet that of large housing estates” but an “atmosphere typical of the first crown.” Later, the exhibition Archi & BD - la ville dessinée, curated by Jean-Marc Thévenet and Francis Rambert and held at the Cité de l'architecture et du patrimoine in 2010, collected a series of other examples, organising them with greater attention to their narrative content. In the catalogue, Philippe Morin writes La Ville extra-muros, an essay that argues that the authors’ views of suburbia are often biased for affective reasons:

(…) comic authors’ views of the suburbs are often idealised. They frequently come from the outskirts, so they use it in their decors as it is more familiar to create a world full of nostalgia. (…) while little used in other arts, the suburbs always had certain respectability in comics because, as an old sub-culture, they always felt more at ease there. (Morin, 2010, pp.108-110).

This view matches the account of Gilles Rochier, author of an award-winning trilogy on the suburbs (2008, 2011, 2017), who states using suburban complexes as setting for his narratives for the simple reason of being acquainted with such reality:

(…) my books are not about an estate, but books that use the estate as a scenario, because I live in a suburban neighbourhood and always did so that decor is the one I master the best. (...) [It is] my universe; I have always been a child of the suburbs. (Lyon BD Festival, 2013)

The Public Administration even explores the idealism endowed with some optimism and an apparent naiveté of some representations. It is the case of the Tendre Banlieue series, which we will refer to later, used as a pedagogical tool in several schools. Even more evident is Oh, ce sera beau! (Trocquet et al., 2013), an urban exhibition and a book prepared in 2014 in Le Havre, for the centenary of the Office Public d’Habitat de la Ville, the public entity that manages the social housing park. It used illustrations of eighteen comic authors - Boucq, François Schuiten, Loustal, Frank Margerin, Philippe Drouillet and others - depicting a colourful optimistic suburban dreamlike universe. Nevertheless, the reality of the suburbs portrayed in comic albums is not always so sweetened: social, psychological, and urban violence are present in numerous stories.

Isabelle Papieau, the author of La banlieue de Paris dans la bande dessinée (2001), identifies some exciting aspects of how comics deal with the subject of the suburbs. Unlike other articles that also focus on the comics representations of the French city but neglect social housing estates (Molina, 2007), Papieau specifically addresses grands ensembles. First, she emphasises the visual elements, the illustrations that often explore chiaroscuro and the night’s rhetoric (Papieau, 2001, p.63), combining a dark and shadowy decor - a noir realism - with marginalised places and symbolically painful stories.

Some comic book illustrators propose an image of a suburb decomposed under a spectral light from two “instrumental” colours: black and white. (...) The pessimism of the chilling images explores unspeakable places, referring to the origins of stigmatisation; the visual record of wrecked, thankless suburbia that graphically dilutes the infinite is supported by expressionist images that communicate, through the scenarios and scenes of life, the despair of those places. (Papieau, 2001, p.51)

The aesthetic coldness of the landscapes, some of which are even identifiable - as is the case with Klishy s/s Bois (Eberoni, Lob, 1980) - is sometimes enhanced by the graphics and the perspectives that accentuate the vanishing points (Papieau, 2001, p.62). Signs of filth and degradation convey the lack of civility: on the outside, garbage on the floor, façades with tags and graffiti; in the interiors, damaged walls and ceilings, especially in the common areas, untidy and modest apartments, with banal decoration and kitschy taste. The constant presence of television and alcohol, the books rare and neglected, also alludes to a low cultural stratum (pp.54-60). Characters, especially teenagers, sometimes defined by some quick strokes only - possibly to “reinforce the notion of anonymity” (p.62) - depict an excluded youth, with a feeling of non-belonging, victim of a flawed school system and unavoidable and long-lasting unemployment (p.67). We thus find the archetypes of deviation, wandering, the spiral of marginality and the menace to public order, alongside the black economy and the delinquency that degenerates social norms and hides in the shadow. In short, Papieau argues that “in tune with the media treatment, comic books explicitly report the avatars of a fallacious micro-society, deviated to collusion and punitive actions” (p.67). Additionally, they manage “illustrating the inhumanity of the utterly monofunctional and socially fractured grands ensembles, embedded in public spaces that comic authors graphically describe their emptiness and pollution” (p.127). These considerations are more or less supported by a set of albums that Papieau analyzes, in particular the Adventures of Lucien and Ricky Banlieue (Margerin, 1981; 1987), Les Bidochon (Binet, 1982), Scènes de la vie de banlieue (Caza, 1977) and Ethnic ta mère (Boudjellal, 1996).

4. Some examples

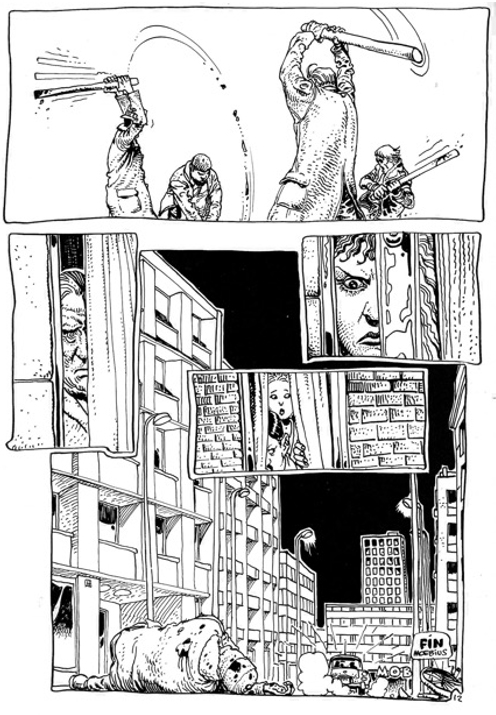

The first comic story in bande dessinée in a suburban neighbourhood is Cauchemar Blanc (Mœbius, 1980) - in English: White Nightmare - published in 1974 in the Franco-Belgian comics magazine L’Echo des Savanes and the only incursion of Mœbius in social realism. Far from his typical fantastic scenarios, this short episode occurs on a winter’s night in a social housing neighbourhood and focuses on racism and interpersonal disputes. Throughout thirteen monochrome pages and agonising graphics (figure 2), we see an Arab man run over, knocked unconscious, and beaten by a group of four racists in a vacant parking lot outside of the apartment buildings. The drawings are masterly balanced, exploring the composition of several partial views, with different zooms and counter-perspectives, reinforcing the graphical power of the black and white contrast and emphasising the dramatic story. This piece also served as a screenplay for Mathieu Kassovitz’s homonymous short film (1991) set at the Fontenay-sous-Bois cité HLM, where Moebius is from, four years before his feature film La Haine (Kassovitz, 1995) filmed in Chanteloup-les-Vignes (Thierry, 2013).

Between 1977 and 1979, Philippe Caza launched the series Scènes de la vie de banlieue (1977) - in English: Scenes of suburban life. Composed of short episodes, it stands out for intersecting the realm of the suburbs and the fantastic through passages to parallel dreamlike worlds borrowed from science fiction. Although its visual interest - supported by meticulous psychedelic and bold coloured aesthetics - largely overcomes its ideological or social commitment, the author describes the dormitory neighbourhoods as dehumanising spaces. In some episodes, at least, he portrays their inhabitants as living-dead and reveals this architecture as a mere scenery, implicitly referring to the alienation and normalisation imposed by these spaces and by the rat race logic of the commuters’ daily routine, popularly translated by the French expression metro, boulot, dodo - literally subway, work, sleep.

Several other series represent the grands ensembles somehow marginally. For example, Jean-Pierre Gibrat launched Goudard in 1980, the story of a young teenager that skates throughout a series of suburban blocks (Gibrat, Berroyer, 1981-82). However, apart from brief allusions to neighbourhood problems and the depiction of some punctual architectural elements, the interaction with the neighbourhood is significantly reduced. In the same period, Frank Margerin provided idealised and humorous versions of the suburbs in his series Lucien (1981, 2008) and Ricky Banlieue (1987) - in English: Ricky Suburb - which explicitly avoid addressing the social problems that were already felt at the time. Although they allow reading some social and cultural aspects (Papieau, 2001), the urban issues remain marginal and grands ensembles a mere feature of the scenery.

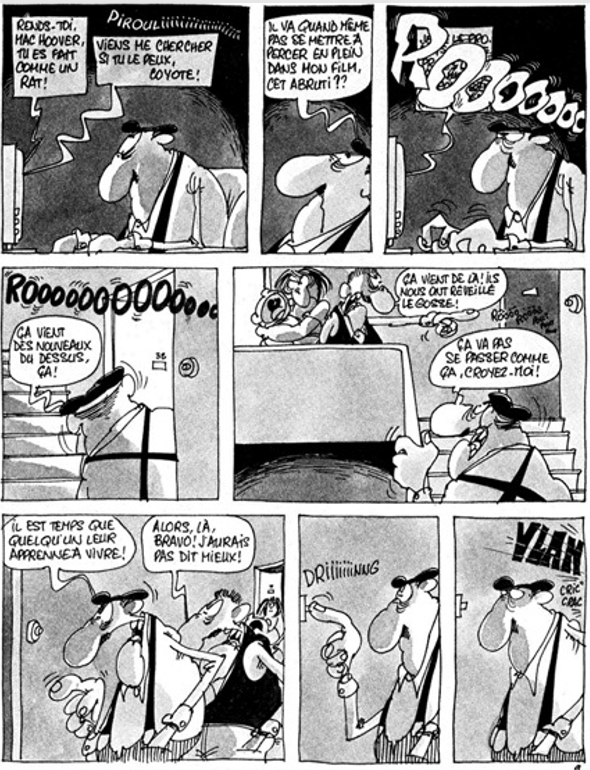

An emblematic and totally different album is Les Bidochon en habitation à loyer modéré (1982) by Binet. The Bidochons are a stereotypical suburban middle-class family, somehow the French bande dessinée counterpart of the American cartoon The Simpsons and the British sitcom The Royale Family, albeit relatively unknown outside France. In this specific adventure, the narrative unfolds in a social housing building, never revealed in an ensemble perspective, but always in partial views, often combining the structure of the comics page with the white frames between the panels used as architectural elements, either walls or slabs. Binet, who also lived in a public-sector estate, depicts, throughout the story, a series of neighbourhood problems and promiscuity due to the cheap and thin construction of these prefabricated buildings: inadequate acoustic insulation, the poor quality of the finishing materials, the garbage chutes and the staircases acting like sounding boards, promiscuous subject to various smells, etc. (figure 3). The story also points out the banality and the repetitive sameness of the architectural solutions and the poor quality of outdoor spaces, besides the distance and physical separation between the city and the estates. “Built away from it all” or stuck between a “boulevard on one side and the railway on the opposite.” (Binet, 1982, p.36). The architect himself is summoned to explain the great challenge of fitting “the maximum number of inhabitants into the minimum space” (p.37). Lastly, we witness the boredom and the depression of the residents and Mrs. Bidochon’s frustration when realising that neighbours are moving into a single-family house without being able to do the same. Despite the book’s caricatural tone, many of the album’s criticisms correspond accurately to the accounts of Bourdieu’s interviews (1993).

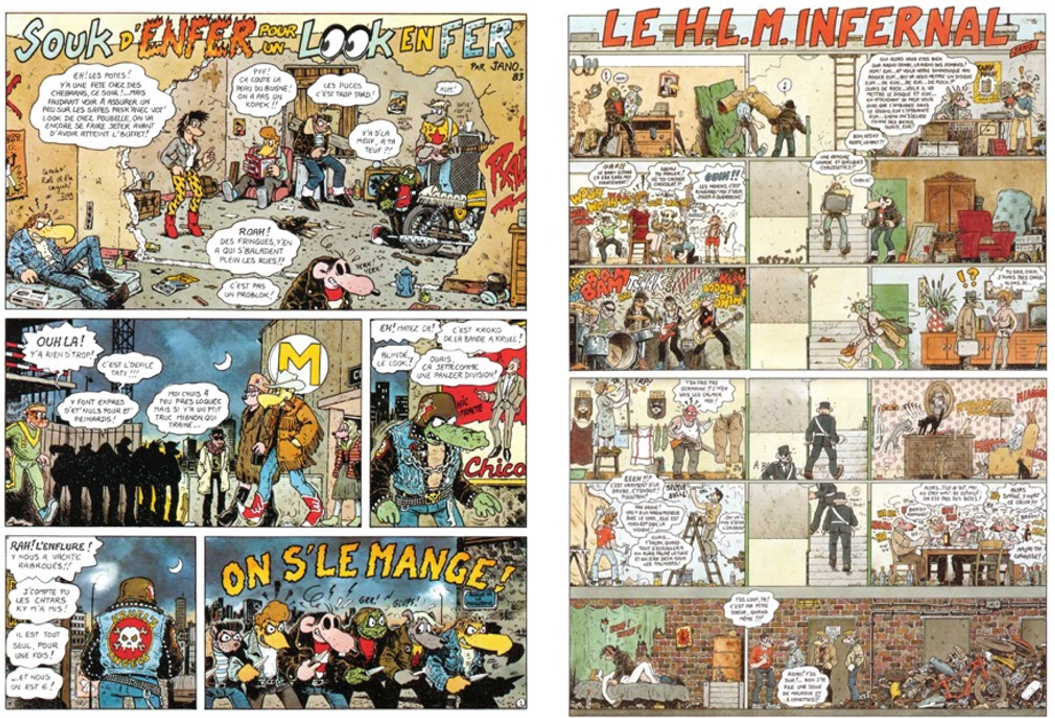

With an optimistic tone, from the 1980s to 2010, Tito’s Tendre Banlieue series (1983, 1984) - in English: Tender Suburb - chronicles the happy adolescence in a suburban environment of a group of teenagers between 7th and 12th grade. With a pedagogical vocation and a sentimental oversimplified manner, its 20 albums address both the issues of that generation as some social problems, from unemployment to illiteracy, drug addiction, AIDS, etc., but always in an upbeat and sweetened version of reality. Architecture renderings are very accurate, and some neighbourhoods are even recognisable, like La Butte Rouge in Chatenay-Malabry - where the author lived - to reinforce the narrative’s credibility. However, as one could predict from the title, the harsh, complicated, and mediatised suburbs are avoided, preferring quieter, ‘tender’ areas (Jacquet, 2015). Jano made the opposite choice, explicitly portraying violence with Kebra (Jano, Tramber, 1981, 1985), published in the comics magazines Hurlant Métal and Charlie Mensuel. Using animal characters, this top-rated series in the 1980s became a symbol of youth counterculture. The main character, a rat - like Art Spiegelman’s Maus, created in the same period, who lends himself to the pun “rat-caille” from the French racaille for scum - lives in a decrepit HLM estate (figure 4). In ‘dirty’ graphics, sometimes monochrome others in full colour, we see terrains vagues, destruction and dereliction, filth, vandalism, delinquency, theft and aggression, revolt against the forces of order, drug trafficking, etc. In short, all the typical clichés of violent suburbia, but with lots of humour.

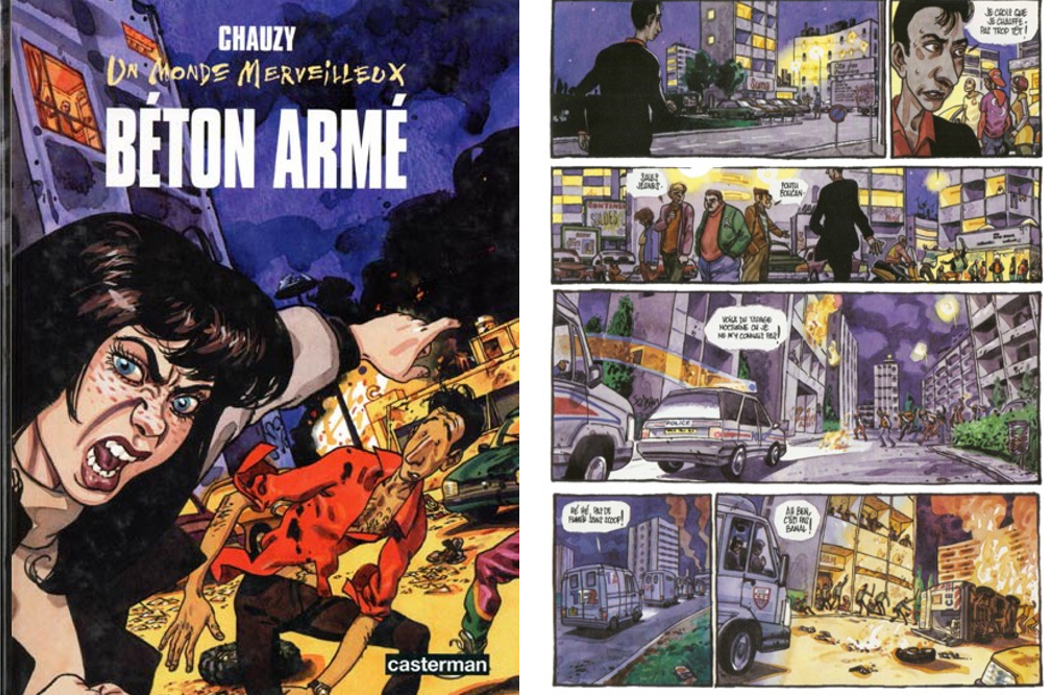

The theme of violence in the estates returned in the late 1990s with Jean-Christophe Chauzy’s Béton Armé (1997) - in English: Reinforced Concrete (armed). The main character finds himself in the middle of the night, alone and on foot, in the middle of a cité; he gets into trouble in a series of caricatural adventures typical of the suburbs portrayed by the media. Supported in facts, exaggerated with large doses of humour and mockery, Chauzy brings intense, colourful and distressing graphics that overcharge the dramatic scenes loaded with brutality and gore. Drawn expressively (figure 5) - like all his albums (Chauzy, 2001) - the architecture of the estates reinforces this effect.

My book received the reactions I expected: I was accused, upon its publication in 1997, of telling nonsense about the suburbs, but the reality proved to be much more spectacular and atrocious than fiction. One of my students (...) accused me of exaggerating, showing what we saw on television. He had been an educator in the suburbs for years, dealing with young people. He recently admitted that he was breaking down and recognises today that what I was saying wasn’t as exaggerated as that. (Chauzy, 2000)

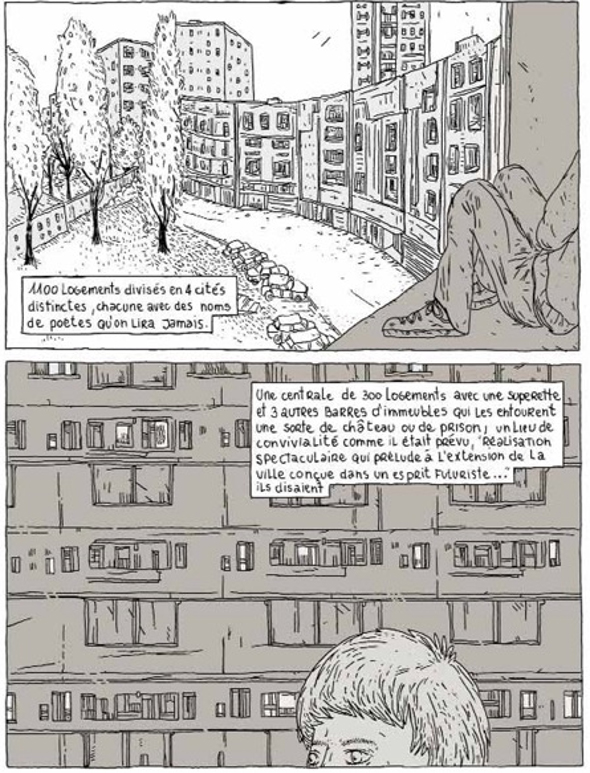

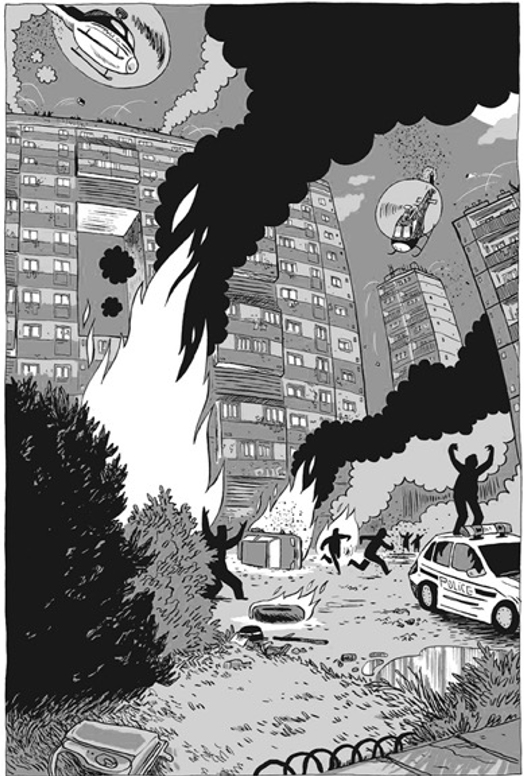

Violence - sometimes extreme, especially in rivalry and reckoning between gangs - continues in subsequent comic series. Le Temps des Cités (2008) - in English: The Time of the Cities/Estates -, set in the 1980s, makes this report by using highly realistic architectural sceneries. However, some more recent narratives, like TMLP Ta mère la pute by Gilles Rochier (2011) - in English: Your mother the whore - or Ligne B by Julien Revenu (2015), opted for simplified, almost childlike graphics in the representation of the characters and the buildings. This graphic economy reveals an especially effective communication of the various forms of violence of these places: latent violence; symbolic violence, with specific social codes; and actual violence, including physical and verbal aggression against people, and the inability of the forces of order to control it. Rochier’s album, which won the revelation prize at the International Comics Festival of Angoulême 2012 - and forms a trilogy about life in the suburbs with the autobiographical Temps Morts (2008), La Petite Couronne (2017) and Solo (2019) - offers a sensitive and raw image of youth. It subtly reveals the mechanisms of social exclusion without great pathos or gratuitous violence. We see grands ensembles arising in the 1970s, way before they became ghettos when some optimism and innocence remained. We then witness the daily life of a group of young people between childhood and adolescence. Their encounter with the secrets of others sets the main plot, and that discovery destroys their friendship and steals their youth away. The sweet childlike monochromatic sepia drawing suggests more than it describes, turning especially effective in transmitting this sad and cruel reality, this profoundly human misery. Ligne B (figure 6), on the other hand, with a more linear drawing and shades of grey, places the narrative in 2005, precisely in the period of the revolt in the outskirts of several cities - émeutes des banlieues. The album tells the story of a father living in the suburbs who makes the wrong choices after constant humiliations. Following his assault on a train by a group of youngsters, being unable to respond, he gets stuck in feelings of anger and helplessness. As a portrait of the malaise of a man reduced to metro, boulot, dodo, the album reveals a growing crescendo from petty crime to countless images of urban riots, in apparently caricatural graphics yet devoid of humorous intention. Despite the simplified graphics of both authors, several real neighbourhoods are recognisable in the albums: the infamous Cité des 4.000 at La Courneuve in Ligne B, particularly the Barre Balzac building, erected in 1963 and demolished in 2011 (figure 7); Montmorency in TMLP, or the famous Tours Nuage, designed by Émile Aillaud in Nanterre, in Rochier’s La Petite Couronne.

5. Final remarks

The corpus of comic strips that addresses grands ensembles and their social problems is considerable, composed of albums of several authors in different periods and with intentions, contents, styles, and narratives that do not compete for a unique precise vision. Moreover, assuming comics might convey a univocal image of this territory would correspond to the mistake - unfortunately quite common - of taking comics, not as a medium or a narrative art form but as a ‘literary genre’. That precise confusion led to the disappearance of photo novels, which was “confiscated by sentimental novels” (Peeters, 1991, p.5). Yet, one thing that we could argue, HLM estates or grands ensembles, due to the stigma that they comprise and through the repetitive nature of its architecture, with the solid “Hard French” image - to borrow the term of Bruno Vayssière (1988) -, quickly overcome the strength of a mere scenery. They immediately assume a relevant role in the narrative and call a series of imageries and representations.

Longtime reserved for the children’s world, mainly featuring adventures and humorous gags, comics progressively conquered an adult audience and, consequently, became intellectualised, acquiring density and the label ‘graphic novel’, and assuming the role of a portrait of social reality, one that explores its multiple connections. Life in a problematic suburb, especially with a recognisable architectural and urban fabric and solid graphic power, quickly becomes fertile material for inspiration. Besides, its character of failed architecture, the image of an inverted utopia, indubitably provides additional interest for the narrative - history of cinema and literature demonstrates it - as dystopic worlds always proved to be more productive than any utopian urban systems (René Boer, 2013; Lus Arana, 2012).

Comic authors imbue their narratives with their personal visions - often informed by their own experience as residents in the suburbs - which might be closer or distant from the stereotypes conveyed by the media and those assimilated by the readers. When narrating dystopian environments and violent gore or enhancing this suburban setting’s anthropological and visual qualities, the architectural issues, social problems, delinquency, or personal feelings become raw material for constructing different approaches and messages. Graphics, whether imbuing the representations with a comic and caricatural effect - even if in apparent contrast with the severity of the themes - sometimes providing it with optimism, other times reinforcing its dramatism, play a determinant role in the way we see (and read) these paper architectures. Perhaps, beyond the general atavisms of urbaphilia and urbaphobia, these graphic narratives might also provide interesting clues about the much-needed right to the city.