Introduction

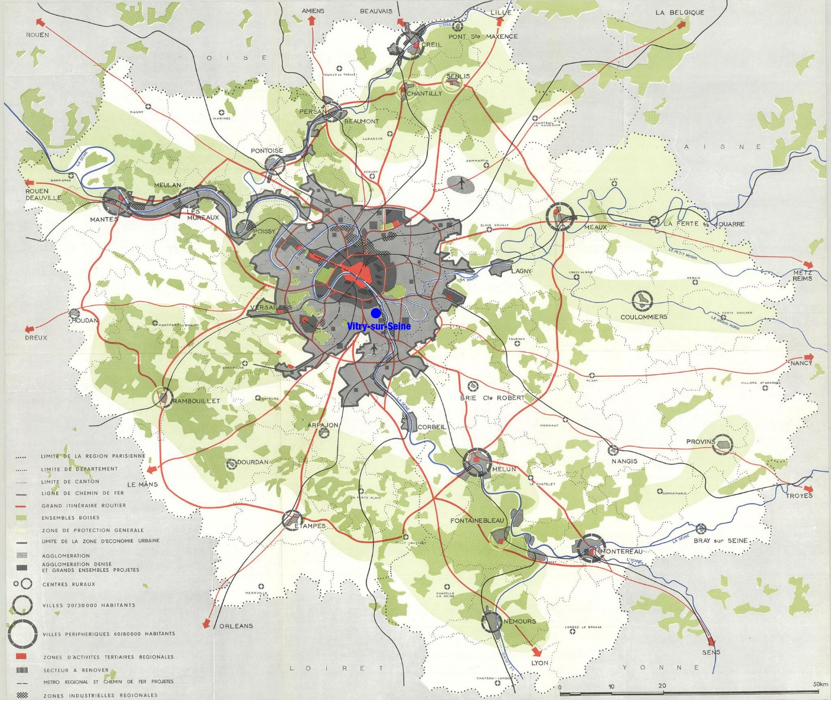

In this article, our aim is to discuss some problems and conflicts emerging from the analysis of the history of a particular grand ensemble in the Paris’ southern red suburbs, built in the last years of the Thirty Glorious years of economic growth after World War II, partially demolished and rebuilt during an ambitious renewal operation in early 2000’s. In the PhD thesis defended in 2014, our strategy was to develop two monographs on specific large-scale housing projects in France and Brazil to understand their parallels and common aspects, revealing the role of social housing in the capitalist societies and their structural problems. Here, we will focus in one side of this wider story, concentrating our attention on Vitry-sur-Seine, emblematic municipality dominated by the French Communist Party since interwar period where social housing was a strategic field on public policies and political rhetorics. During the so-called ZUP (Zone à Urbaniser en Priorité) years, especially after the inauguration of the Fifth Republic in France (1958), the state set in motion an ambitious plan to reorganise the banlieue, which envisaged the construction of several grands ensembles around Paris, as an indispensable measure to balance rural migrations towards Paris and reduce the population density of the crowded and run-down “îlots insalubres”.

Many recent works have been published in France on the history of grands ensembles, in an at-tempt to understand the enormous transformation to which these spaces and objects were subject-ed. From symbol of a broad constructive social project, the huge housing estates produced during the thirty glorious years of spectacular growth of the French economy in the post-war period, especially in the 1960s, came to be seen as spaces of segregation, violence and social problems, occupying the place previously reserved for bidonvilles and self-built territories, also known as “pavillonaire”.1 It is mainly up to historians of the city, architecture and urbanism to recover the original meaning of the grands ensembles, as does Danièle Voldman: “Les grands ensembles sont aujourd'hui perçus comme des repoussoirs et des symboles d'une relégation sociale; ils ont pour-tant été, en leur temps, l'objet d'une des plus belles ambitions du XXème siècle: offrir un logement décent à tous.” (Voldman, 2010, p.201)

From monographic approaches over one particular project or grouped under the work of one architect or institution to sociological perspectives or political histories, grands ensembles became recently privileged objects of urban and social history in France. Even if the ordinariness of Cité Balzac didn’t claim for specific work in architectural history field2, as one of the less exceptional examples of many grands ensembles with similar stories, after its spectacular, mediated and traumatic renewal, our hypothesis is that this particular territory describes a perfect cycle, showing the limits and contradictions of social housing as a modern utopia, its crisis and contemporary conditions. Cité Balzac interests us not only because it was one typical 1960’s project, symbol of a new way of living and of the modernization of housing construction techniques and policies but also because it suffered intensely a process of degradation and stigmatization, being characterized a little more than a decade after its inauguration by social problems, violence, conflicts involving youngsters, unemployment, drug trafficking and the concentration of immigrants and poverty. From ZUP, Cité Balzac shifted to Zone Urbaine Sensible (ZUS), a euphemism that inserts it in the cartography of problematic suburbs, relegated to those who could not choose where to live through not so subtle economic or ethnic differentiations.

Here, we will shortly present the construction of the Cité Balzac, inscribed in this ambitious urban operation in the southern limits of this red suburb3, its occupation and the conflicts that lead to its physical and social metamorphose through one project led by local communists and funded by the National Agency for Urban Renewal (ANRU). The logics of ANRU imposed the demolition of the gigantic housing blocks, towers and slabs, substituted by new typologies and new policies, favouring a controlled gentrification process, under the notion of “social mixing”. This synecdoche of the history of rise and fall of this modern utopia - a decent house for every family, materialized through a particular architecture - hard, statistic or even sordid modernism that radically trans-formed the urban landscapes in France, can be foreseen following the singular history of the Cité Balzac. Through the critical and transdisciplinary gaze over these episodes, conflicts and trans-formations, we can understand some limits of social housing political and economic functions and the permanence of the urban crisis in contemporary conditions. Through a “simultaneous understanding” of the history of the subject and of this territory, confronted with the diachronic sequence of the short time of events reconstructed from local public archives and the press, we will seek to understand the general meaning and contradictions that surrounded the realisation of large social housing estates and that ended up calling into question the function of these policies.

Tumulte dans l’ensemble: the case of Cité Balzac

Cité Balzac is part of the Grand Ensemble Nº4, built in the late 1960’s in Vitry-sur-Seine, following the plans of the Construction Ministry, led by former French resistant Pierre Sudreau (1919-2012) during Charles de Gaulle government (1959-1969). Sudreau embedded the functionalist urbanism doctrines as did Paul Delouvrier (1914-1995), responsible for conducting the Plan d’Organisation Générale de la Region Parisienne (PADOG), approved in 1965 to “put some order in the urban mess” that characterized the Parisian region after World War II, following de Gaulle’s words4. Vitry-sur-Seine, since 1925 until recently5, is ruled by the French Communist Party (PCF) as Ivry-sur-Seine, strategic territories of the municipal communism that emerged in the interwar years. During the Trente Glorieuses period (between 1945-1974), grands ensembles became the rule as urban model and iconic symbol of the État Providence. Social housing was a priority in communist administrations for evident reasons, transforming these territories in a collection of elaborated experiences in the field6. Since the 1920s, when the first blocks of 'Habitations à Bon Marché' (HBM) were built to house the precariously sheltered workers of the industries that settled around Paris, to the present day, the commune has been constructing both paradigmatic and ordinary examples of social housing projects7.

The characteristic achievements of the interwar HBMs were severely criticised by the modernists and the generations that followed, finding a certain rehabilitation in our days, praising their scale, more compatible with the traditional French cities. Le Corbusier (1887-1965) was one of the critics of this model of living, calling the buildings “sordid ante-chambers of the city”8; his fellow countryman, the poet Blaise Cendrars (1887-1961) also vociferated against the way of life inside today's valued HBM flats. Part of the criticism focused on the ineffectiveness of public production from the achievements of that moment, either HBM or garden city; both models would be unable to face the growing housing deficit, especially after the destructions of the World War II. Large-scale housing production based on industrialized construction would emerge from the 1950s as the only possible answer to face the problem, replacing the HBM-type brick buildings as a design paradigm, loaded with ornamental details characteristic of artistic masonry.

Vitry-sur-Seine’s Municipal Archives (APMV).

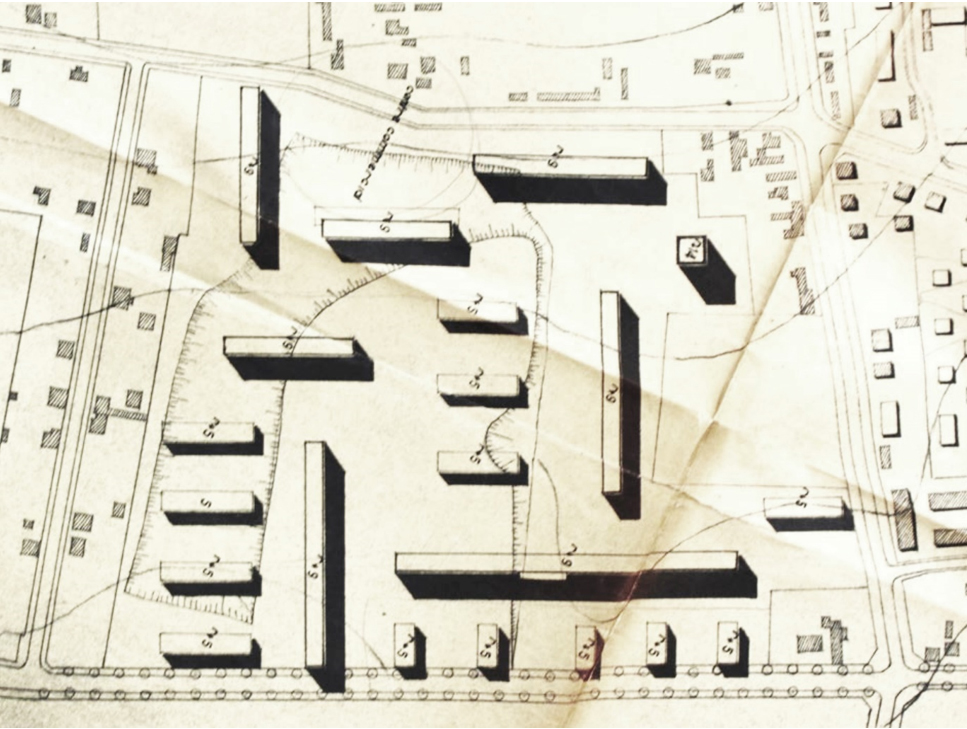

Source: Figure 2: Cité Balzac building site in late 1960’s

In Vitry, we can find examples of early red bricks buildings that materialized a typology associated to the French version of the Cité-jardins or radical experiences such as the Charles-Floquet project by Marcel Lods (1891-1978) and Eugène Beaudoin (1898-1983) from 1933-35, using prefabricated concrete elements, among other more ordinary post-war “hard French” architectures, some of them greatly inspired of the Marseille’s Unité d’Habitation by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret (1896-1967) and other modern typologies built during the ZUP years9.

Cité Balzac makes part of the ambitious plan of massive urbanization and city centre’s renewal, involving the demolition of a substantial part of the dilapidated medieval urban core and the construction of dozens of new apartments blocks, public equipments, parks and commercial facilities.

Ainsi naissent les cités nouvelles appelées 'grands ensembles' à partir des années 1960. Ce consensus, né de l'urgence de la crise du logement, est partagé par tous: les maires poussés par leurs électeurs qui veulent des logements neufs; les responsables politiques; les fonctionnaires du ministère et des directions départementales; les architectes et les maîtres d'ou-vrage. (Annie Fourcaut in Fourcaut, A. e Harismendy, F. (orgs.) 2011, p.211)

Vitry-sur-Seine’s Municipal Archives (APMV).

Source: Figure 3: Cité Balzac original project by Charles Sebillote

The film Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle (1967), by Jean Luc Godard (1930-), reflects the ambiguities and contradictions of a society that was voluntarily modernising itself, in conflict with the new forms of life in metropolises and the prospects of the mass consumer society. The Parisian region is one of the female characters in the film, among others, who prostitute them-selves while delivering reflections and 'lessons on industrial society', 'introductions to ethnology', echoing the critique and discourse associated with the grands ensembles in the same film through different characters.

The first project to the urban operation was made by the architect Charles Sebillote (1908-?), ac-cording to the Ministry of Construction prescriptions. However, the communist municipality re-fused the preliminary plan, demanding more social housing that could face the needs of the emerging industrial workforce, composed of French middle class but also European and north African migrants. Using the French Communist Party’s political prestige, in expansion at that moment, Vitry’s mayorship imposed the Italian-born architect Mario Capra (1923-1971) as the responsible for the operation, in an attempt to control the major urban transformation and build modular experiences in the red suburbs. The urban project developed by Capra was greatly in-spired of Brasília as a model of a utopic city designed from scratch to foster new relations be-tween citizens of different social conditions under a complete rationalist urban realization. According to Bruno Vayssière, one of the first critics to write about the hard French, statistic or even sordid architecture characteristic of the Trente Glorieuses, the relation between Vitry’s Grand Ensemble project and Brasília was evident: Le grand ensemble de Vitry sur Seine, une Brasília rouge précurseur: dès le debut des années cinquante, la rénovation urbaine à coup de tabula rasa inspirée des bombardements va proposer de véritables villes contemporaines dans la ville ancienne. (Vayssière, 1988, p.228)

During late 1960s, Oscar Niemeyer (1907-2012) was self-exiled in France, designing not only the siege of the Communist French Party but also other important projects on other municipalities ruled by the communists through strong and friendly connections with the PCF10. Brasília’s yet recent fascination was one present reference on the imaginary of the protagonists of the municipal communism movement that dreamed of building the modern “symbolic capital” of the red suburbs the surrounded Paris (Bellanger and Mischi, 2013).

Ivry-sur-Seine, the Siamese sister city between Vitry and Paris, was an iconic communist municipality. Surnamed Little Moscow is a strategic political base of important PCF leaders like Mau-rice Thorez (1900-1964), Georges Marrane (1888-1976) and the Gosnat family11 and an iconic territory for the realizations of municipal communism, such as social housing complexes, public health, education and leisure facilities on the Southern bastion of communist territories around Paris.

Planned to foster the expansion of the local population from less than 50.000 to 100.000 inhabit-ants within few decades, the massive operation composed of high rise precast concrete blocks and low-rise slabs transformed not only Vitry’s landscape but also its social structures. Capra’s plan organized the project in different sectors in order to absorb the demographic explosion characteristic of the post war years but also to offer decent housing to French middle-class families poorly installed on the “ilôt insalubres”, whose demolition was considered a priority by the Construction Ministry policies. Cité Balzac was the most segregated sector of the ZUP established in Vitry, composed by different housing blocks built under different programs designed to offer housing to the population evicted from inner Paris, emigrating families coming from the countryside and to former slums inhabitants. The construction works started in 1967 with the erection of three high-rise blocks inspired of Le Corbusier’s Marseille Unité d’Habitation and were accomplished around 1974, when the last of the smaller blocks were delivered to its first inhabitants.

The social organization of heterogeneous populations can be read through the architectural com-position of the ensemble: the three Marseille-inspired ABC-DEF-GHI blocks and the low-rise slabs around them were dedicated to typical HLM financing schemes and populations, while a longer block placed in the limit of the plot housed higher stand apartments with superior rents, mainly occupied by French middle class. Other three smaller blocks were dedicated to host populations moved from the Parisian “ilôt insalubres” situated on the 13ème arrondissement; a Cité de Transit, temporary residence for former slum residents, among them many Portuguese, existed also in Cité Balzac during its early years, being demolished in late 1970’s. Until the recent renovation, also a Foyer de travailleurs célibataires lodged single African migrants working in France and willing to bring their families in. The local newspaper Vitry Hier, Aujord’Hui et Demain12, published by the communist municipality follows and reports the construction of the different phases of the Grand Ensemble project but also the clashes between first residents and authorities.

After some years of pacific coexistence of these three different social groups, the white and French middle-class started to leave the complex, stimulated by the savings accumulated during the thirty glorious years and by the policies of the liberal right government of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing (1926-2020) in late 1970’s that fostered private-property policies on housing. The empty apartments were progressively occupied by migrant families, mainly from North Africa but also from European countries like Portugal and Italy or by poorly integrated pied-noirs, French citizens re-turning from former colonies such as Algeria, independent since 1962. The conflicts between the incoming population of the housing projects and the former Vitry citizens started to become violent in the early 1980’s when a youngster was killed by a janitor, giving place to clashes and conflicts mediated by the police and strong stigmatization on the press. The lack of maintenance of the collective spaces within the buildings and its infrastructures, associated with the pathologies of the experimental construction techniques employed to build in unprecedented speed and scale helped to raise the tensions between neighbours, aggravating the segregation and stigmatization of the Cité Balzac and its inhabitants.

In early 1980’s, the transference of a group of African workers from another suburb controlled by the right wing to Vitry opposed the communist mayorship to the African Muslim immigrants in an episode explored in national political disputes and press to denounce communists contradictions. The mayor took part in an action to avoid the transference of the Mali immigrants, showing some limits on communist’s notion of integration and giving fuel to both right wing and socialist’s critiques.

At the same time, in the national level, the Socialist government of François Mitterrand (1916-1996) started to act in the sensible neighbourhoods, developing positive discrimination actions on these problematic territories and demolishing some of the blocks built in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s such as parts of the Cité des 4000, in the northern suburb of La Courneuve. Despite of the social actions undertook by a different approach of these impoverished neighbourhoods known as “politique de la ville”, the relegation process on Cité Balzac kept escalating, helping to concentrate high rates of unemployed and undereducated populations and frequent episodes of delinquency such as drug trafficking and robberies. In early 1990’s, the commercial facilities built in Cité Balzac were demolished after being left unoccupied by store owners tired of being constantly robbed by local youngsters. Progressively, the local social housing company, responsible for the administration and the attribution of the apartments to the families, had to face the rejection of the families to the possibility of living in Cité Balzac. Frequent demands of dwellers expressed the will of getting an apartment anywhere but in this stigmatized complex.

In 2002, when the youngster Sohane Benziane (1984-2002) was burnt alive in a trash container in one of the Cité Balzac blocks by her ex-boyfriend, the national media turned again their attention to the complex, focusing the episode as a symbol of the conflicts that were spread out on social housing complexes opposing and challenging French revolution’s moral and limits. In 2005, sever-al episodes of violence in the suburbs spread out an intense wave of contestation and altercations between youngsters and the members of the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité (CRS) in reaction to the death of three youngsters persecuted by the police. These mediated and politically explored episodes of a history of violence and tension frequent since late 1970’s that suddenly and constantly escalates until nowadays has been analysed in different perspectives. The anonymous collective Comité Invisible in its manifesto L’insurrection qui vient (2007) situated in these struggles that took place in the French suburbs as an episode of a disruption in the politic field:

What was new wasn't the "banlieue revolt," since thatwas already going on in the '80s, but the break with its established forms. These assailants no longer listen to anybody, neither to their Big Brothers and Big Sisters, nor to the communityorgani zations charged with overseeing the return to normal. (…) This whole series of nocturnal vandalisms and anony mous attacks, this wordless destruction, has widened the breach between politics and the political. No one can honestly deny the obvious: this was an assault that made no demands, a threat without a message, and it had nothing to do with "politics." One would have to be oblivious to the autonomous youth movements of the last 30 years not to see the purely political character of this resolute negation of politics. (Comité invisible, 2007, p.24-25)

In the public opinion, especially in the early 2000s, modern architecture was considered responsible for these violent episodes, contributing with the tacit condemnation of the forms and techniques that helped to raise the conditions of living of middle-class families some decades earlier. The urban comedy C'est la faute a Le Corbusier, developed by Louise Doutreligne from the opinion of an inhabitant not far from Cité Balzac represents through a play the cultural rejection of the blocs, towers and slabs concrete architecture. The television show Droit de réponse in 1982 confronted the opinion of the inhabitants to the architects Fernand Pouillon (1912-1986) and Ricardo Bofill (1939-) around the question: Shall we destroy the grands ensembles?13, showing that the image of these housing complexes shifted from solution to problem within few decades.

Cinema has used these housing territories as an expression of cities and social metamorphosis, as a metaphor of the idiosyncrasies of the consuming society characteristic of post war and as battle field for the functionalist urbanism critique. Modern architecture and rationalist urbanism were perceived as tools of cultural homogenization and political control, as denounced by the situationists, specially by Guy Debord (1931-1994) in La Société du spectacle (1967). In 1990’s, films like Mathieu Kassowitz’s La Haine (1995) or Ma 6té va cracker (1997) placed in these territories the conflicts between different layers of the French society and their correlated spaces.

The demolition of the problematic blocks, considered and experimented since 1980’s with limited results, appeared as a universal solution employed with different emphasis by both right and left wings to demonstrate the power and the commitment of French national government to re-establish the control over the popular territories. If this solution has been experimentally tested since 1980’s in order to open these segregated spaces and integrate them to their surroundings, avoiding the poverty and social issues concentration on specific parts of these projects, after the 2005 fires, with the emergence of a right-wing government, demolition became a mandatory procedure in order to intervene on the grands ensembles.

Rénovation, démolition, résidentialisation

The creation of the National Agency for Urban Renewal (ANRU) by the Jacques Chirac (1932-2019) government gave place to a new wave of radical transformation of the housing complexes, intensified during the Nicolas Sarkozy (1955-) mandate. Cité Balzac is the epicentre of the demolitions14 related to an ambitious operation by the National Agency for Urban Renewal (ANRU), planned in accordance with the Vitry’s communist municipality, also inscribed in an Operation of National Interest (OIN) and structural transport articulation of the Paris Region, the so-called Southern Arc of the Grand Paris project.

The project provided for the demolition of almost a thousand housing units in the complex and the construction of two new units for each demolished unit, spread across the various districts of the city. This opportunity was seen by the municipal authorities as leverage for the resumption of housing construction in the commune, on a downward trajectory since the glorious thirties, while 'solving' the problems of Cité Balzac through the forced introduction of a supposed social mixité, opening up public land to private developers and other income strata as a strategy to break the pocket of poverty that was concentrated there.

Following the logics of the ANRU, for each new social housing unit to be built, one had to be demolished, situated inside the defined perimeters that concentrated social issues. The Sensible Ur-ban Zones (ZUSs) were elected by then as epicentres of the spectacular demolitions widely mediated and celebrated by the government as definitive solution of the social problems associated with these particular architectures. The sociologist Renaud Epstein, in a detailed analysis of the typical processes of renovation and reconstruction, makes a distinction between renouvellement and rénovation urbaine, differentiating the reform of sets experimentally tested in the most varied forms over a quarter of a century of 'politiques de la ville' and the renovation, which would necessarily go through the public and media impact of a major demolition and transformation of large groups.

Author, 2014.

Source: Figure 5: The different phases of the Cité Balzac during the renovation, demolition and residentialization works in 2014

Il faut dans le même temps faire disparaître les stigmates qui réduisent leur attractivité ré-sidentielle, ce qui justifie des démolitions de grande ampleur d'immeubles parfaitement salubres. Em même temps, ces démolitions libèrent des vastes terrains sur lesquels les aména-geurs peuvent dessiner librement de nouveaux morceaux de ville. La démolition de barres et de tours, remplacées par des maisons et de petits immeubles collectifs, banalement disposés le long des voies nouvellement crées, permet d'opérer une transformation aussi profonde que visible, à la mesure du caractère spectaculaire de la disparition, dans un nuage de poussière et un odeur de poudre, de ces quartiers hors normes. (Epstein, 2013, p.95)

From Vitry to the national plan, the publicity of Sohane Benziane episode levelled the leader of the feminist movement “Ni putes ni soumisses” to an important position on the Sarkozy government but also helped to establish unique conditions to the Vitry-sur-Seine’s renovation project, ap-proved among the first ANRU operations. For each apartment demolished at the Cité Balzac, two new housing units were to be built in Vitry. The three high-rise blocks and some parts of the lower slabs were appointed to be demolished in order to integrate the housing complex in the surroundings, avoiding the enclave condition of the Cité Balzac and erase its negative image. Even the name of the complex was to be changed, giving place to a new neighbourhood called Petit Vitry, liberated from its traumatic past. Under the abstract notion of social mixing, the impoverished population of the Cité Balzac was spread out and installed on other social housing complexes or even on other municipalities and the middle-class was attracted to the new constructions with policies that encouraged private property acquisition through affordable conditions.

The remaining blocks were renewed and went through “résidentialisation” operations, neologism that stands for interventions in order to improve the energetic conditions of the apartments and, above all, install security systems, and establish limits between private, collective and public spaces, avoiding the grey areas where part of the traumatic episodes took place. One important source to grasp the chronology of the urban renewal operation in Vitry is the local newspaper Les quatre pages, published by municipality as part of participatory strategies to communicate the phases of the project to the inhabitants and promote activities with them through the local social centre. Epstein describes the logic and the mechanisms of the “résidentialisation” that aimed to transform the social housing complexes in ordinary parts of the urban fabric, imposing new dynamics and rules:

la résidentialisation doit simplifier la gestion urbaine en clarifiant les domanialités et donc les responsabilités en matière d'entretien et de nettoyage des différents espaces, entre les collectivités territoriales et les bailleurs sociaux ou syndicats de copropriétaires; elle doit aussi contribuer à la sécurisation des lieux en rendant plus difficile l'appropriation des espaces extérieures et des halls d'immeubles par les groupes de jeunes à l'origine de nui-sances et de dégradations; enfin, elle doit aussi contribuer à la sécurisation des lieux en rendant plus difficile l'appropriation des espaces extérieurs et des halls d'immeubles par les groupes de jeunes à l'origine de nuisances et de dégradations; enfin, elle doit responsabiliser les habitants, les incitant à respecter les parties privatives et communes de leur résidence. (Epstein, 2013, p.95)

The remaining public land was occupied by lower scale developments and “eco-friendly” architectures, marketed as a viable investment with optimistic valorization possibilities supported by expected improvements on public transportation system enhancing the direct connection to Paris. At the same time, other social housing projects of exceptional quality and architectural significance were recognized by heritage institutes and administrations that questioned the demolitions and recommended the preservation of several grands ensembles as a built testimony of a modern utopia that shaped French landscape in the 20th century.

Having in mind that Vitry-sur-Seine was included in the perimeter of the Great Paris project, aiming to expand and improve the public transportation network as a strategy to expand the limits of the French capital over the surrounding municipalities, it is impossible to consider Cité Balzac’s project as a punctual operation disconnected from the plans to integrate these problematic suburbs in the more socially homogenous territories that nowadays characterizes Paris intramuros. Apparently, what happened in 1860 with the expansion of Paris limits with the annexation of its surroundings by Haussmann and the extension of social housing territories over the last defence walls from 1930’s onwards, may be happening again in consequence of the integration of the “red suburbs” around Paris with the expansion of public transportation networks. If in its glorious years Cité Balzac received some of the former inhabitants of the Îlot insalubre Nº4, as described by Henri Coing in 1966, once again the impoverished dwellers are being pushed away, forced by sophisticated segregation mechanisms to move to other limits or to worst housing conditions. At the same time, the renovation left new void plots to be occupied by real estate investments with few or any social concerns, where the middle class unable to afford Paris prices found an opportunity to buy an apartment.

Final notes or the vicious circles of social housing

Housing in an intriguing object of interdisciplinary studies that articulates measurable needs that can be stablished for specific layers of the society through financing and access conditions with more abstract and subjective desires, impossible to satisfy or precisely describe, as the historian Danièle Voldman (2010) would put it15.

Additionally, there is a hard conciliation between architectural optimism regarding the great housing projects and the political critics of its structural role in controlling urban and social dynamics. In France, this fracture and frictions can be observed in detail through the recent history of one particular territory and its uncertain near future. Cité Balzac is an emblematic example precisely because it is not an exception or an application of a general rule: its history unveils elements of the general and particular dynamics involved in the metamorphosis of the grand ensembles.

Even in a communist mayorship, we can observe and understand these recent episodes that turned one page of the history of this housing complex as effects of an “urban realpolitik”16 as defined by Sfeir (2013). The municipality is associated with national funding and agencies led by governments of different political orientations and private real estate developers to operate a controlled gentrification program using the notion of social mixing to transform the economic and ethnic profile of the inhabitants of a specific part of the city as a strategy to intervene in the alleged source of the frequent urban conflicts. The typical “hard French” architecture of the glorious post-war years was the more visible and concrete aspect of these transformations. Hero, villain and victim of a tragedy, architecture was by nature inscribed in a vicious circle of the social housing contradictions, as described in a political economy perspective by Butler and Noisette (1983):

Les termes de « logement social » désignent un phénomène historiquement et géographiquement bien particulier: une classe sociale est, en tant que telle, privée de la maîtrise de son habitat et se trouve « logée » par une autre. Sauf à vider le concept de tout sens, on ne peut le rapporter à n’importe quelle forme de ségrégation sociale dans l’habitat, ou à n’importe quelle traduction spatiale d’un rapport de domination ou d’exploitation. La notion de logement social comme les réalités qu’elle recouvre sont en ce sens liées à l’évolution des sociétés capitalistes occidentales. (…) Depuis le XIXème siècle, l'économie et la société françaises se sont profondément transformées. Mais les caractères et les fonctions du logement social demeurent indissolublement liés à sa nature, quels que soient ses avatars formels ou ceux des politiques mises en oeuvre. Par nature, il est à la fois produit, outil et lieu de contrôle et de ségrégation. Chacun peut l'observer quotidiennement dans l'espace urbain. (Butler and Noisette, 1983, pp.6-7)

Friedrich Engels (1820-1995), when analysing the housing question in capitalist industrial societies in 1872, identifies a bourgeois solution method developed during the Haussmannian urban reforms in Paris that describes vicious circles that seem active at the particular history of the Cité Balzac, metaphor or synecdoche of similar histories in other cities and societies.

In reality the bourgeoisie has only one method of settling the housing question after its fashion - that is to say, of settling it in such a way that the solution continually poses the question anew. This method is called "Haussmann." (…) By "Haussmann" I mean the practice, which has now become general, of making breaches in the working-class quarters of our big cities, particularly in those which are centrally situated, irrespective of whether this practice is occasioned by considerations of public health and beautification or by the demand for big centrally located business premises or by traffic requirements, such as the laying down of railways, streets, etc. No matter how different the reasons may be, the result is every-where the same: the most scandalous alleys and lanes disappear to the accompaniment of lavish self-glorification by the bourgeoisie on account of this tremendous success, but they appear again at once somewhere else, and often in the immediate neighbourhood. (Engels, 1872, pp.68-69)

Inscribed in a wider national strategy, even the communist municipality seems to be involved on the pragmatic capitalistic dynamic that involves periurbanization, relegation and gentrification, as described by Jacques Donzelot (2009) when analysing contemporary dimensions of urban trans-formations that takes place in these problematic suburban territories.

La prise en compte de la fermeture entre ces 'états de ville' que sont la relégation, la périurbanisation et la gentrification permet de mesurer la véritable portée de cette logique de séparation: une diminution du sentiment d'interdépendance, la tentation pour les petites classes moyennes de renvoyer la population reléguée vers son pays d'origine, du moins d'incriminer la cause de sa présence sur le territoire national, cette 'mondialisation' 'par le bas' qu'est l'immigration vécue comme déstabilisant la société. (Donzelot, 2009, p.56)

The recent history of the grands ensembles in France, even through a particular case, is telling of the transformations of a typical modern social and architectural utopia. The persistence of housing question and urban crisis in contemporary societies reveals not only the end of modern architecture as Blake17 and Jencks18 proposes but also marks the destruction of a social project that started to be considered in the late 19th century, with progressive urbanization that followed industrialization in Europe. The demolition of social housing “towers and slabs”, symbols and objects related to a global history (Urban, 2012) can be understood as symbol of the fall of the welfare state promises. At the same time, the renovation and new constructions try to respond to contemporary issues, revealing and creating new contradictions. From a modern utopia, social housing became a contemporary issue, showing that the articulations of architecture, urbanism and politics are quite more complex than some narratives developed to describe an historical process under development would pretend.