Introduction

The northeastern region of Trás-os-Montes in Portugal is a paradigmatic area of out-migration, from the colonial migrations to Angola, Mozambique and Brazil to the ones to western and northern Europe during the Estado Novo, and the more recent migrations post-2008 crisis. The area went through dramatic demographic losses, accounting for a third of its population between the 1960s and 2000s. But it is also one of the areas with the highest rate of new residents, a great part of them coming (back) from France. The back and forth of inhabitants is only one form of the mobilities one can encounter: at the border of Spain, Trás-os-Montes is recently revisiting its transcultural heritage, such as the one of the Sephardic Jewish community or the Mirandese minority.

Following an ethnographic fieldwork conducted between 2018 and 2020 in the region, I explore the dynamics of place production in such a cultural space of encounters, conflicts, and renewal between several communities, in a region which has historically functioned as a transitional space. The paper focuses on the city of Bragança, and three villages located in its vicinity in the Montesinho Natural Park. It also largely deals with a particular type of migration, return migrations, hence contributing to a better understanding of how return migrations are conceived of by local, regional, national and European actors.

This piece participates in the discussion linking migration and place-making in borderzones, and builds on previous research on that issue (Desille, 2018). The conceptualisation of place-making is highly influenced by the works of feminist geographer Doreen Massey (1991, 1999). As she argued, places do not house single communities, but are arenas of multiple identities in conflict. As those identities fluctuate, places are not static. Massey supports “a sense of place which is extroverted, which includes a consciousness of its links with the wider world, which integrates in a positive way the global and the local” (Massey, 1991). With this view, place-making aims at repositioning a place in its wider relations with other spaces. The empirical case hereafter presented takes into account the experiences of individuals who stay, circulate, and return, in order to observe acts of place-making and border-making. Findings make evident the fact that these experiences are lived in tension with local, regional, national and European governance, i.e. municipal service delivery, regional infrastructure projects, national funding and European free circulation principles. It is this tension precisely that nuances Massey’s “progressive sense of place”: I have found a discourse and policy gap between “idealised” returning migrants and their selective support by institutions vs. the actual contribution of returning/circulating migrants to the making of this border zone. Findings also show that for the local government’s point of view, returning migrants, although they represent most of migrants in the area, are not conceived as active place-makers, and do not see their potential tapped in by municipal actors.

Throughout the article, I will demonstrate that the villages under study are indeed embedded in multiple networks and undergo constant transformations along with migratory (in and out) layers. Their transformations fit more open conceptualisations of border zones such as “contact zones” (Pratt, 1991).1 In the field of migration studies, contact zones are characterised by the encounter of different social groups, sometimes cooperating but often in conflict; differences and exclusion; the geographical exception; and the fading multiethnic contact caused by nationalism (Cohen and Sheringham, 2017). More recently, Cohen and Sheringham argue: “we notice highly congruent descriptions of emerging identities that draw selectively on the past and engage selectively in the present [...]. Difference is frozen or defrosted, transcended in everyday relations or sustained behind closed doors” (2016, p. 55). In that sense, the research presented here is one possible development of a contact zone, through the tensions existing between different levels of administration and discourse.

In what follows, I describe the relation between migration and place-making in the border region of Trás-os-Montes. First, I locate this study in the wider discussion on (mostly return) migrations and place-making in villages and small towns in Portugal. Second, I briefly describe the methodology I used, including stays in the region, in-depth encounters with transnational families and video work. Third, I turn to the tension between the categorisation of the area as an “inner territory” and more recent attempts to bring the area closer to Spain and the rest of Europe. Fourth, I show the extent to which these attempts are not only based on infrastructure but are also included in a new narrative of openness and internationalisation. Fifth, I turn to the example of one village of the Montesinho Natural Park, which I argue is strongly embedded in local, regional, national and international networks. Yet, I show in the sixth section how this type of embeddedness is discarded by the region and not portrayed as an example of openness. This is also apparent in the institutional programmes that should support emigrants and returnees, but are in fact unknown or perceived as unfit to the main beneficiaries. In the concluding section, I circle back and discuss the discrepancy between actual place-making and the social engineering the institutions aim at.

Return migrations in Portugal (and beyond)

Out-migration is structurally embedded in Portuguese society (dos Santos, 2013). As of 2020, Portugal is still the European country with the largest group of migrants: 22% of Portuguese live abroad (Pires et al, 2020). From the end of the 19th century, emigration enabled to release pressure on the national economy and a majority of Portuguese migrants reached Brazil, the USA and Portuguese colonies in Africa (Pires et al, 2010). The ambivalent relationship of Portugal with its migrants reached a peak during the dictatorship (1926-1974): out-migration was extremely controlled by institutions, but irregular migration took place at the highest scale with hundreds of thousands of Portuguese leaving the country, particularly from the 1950s to the 1970s (Pereira, 2012). Migration provided individuals with survival means, while the country benefited from foreign currency. The clandestine out-migration of Portuguese during the dictatorship is referred to, in Portugal, as emigração a salto, which would roughly translate into leaping emigration. O salto, or the leap, was used to describe one’s illegal crossing of the Hispano-Portuguese border as well as the indefinite journey that would follow until reaching France or another European country. O salto is a fundamental event in the collective memory of the many Portuguese that lived and live in France, and the narratives and images associated with this journey participate in the production of the emigrant figure (Espirito Santo, 2013). The exile of Portuguese during the dictatorship corresponded with a slowdown in the State-organised recruitment of foreign “guestworkers”, notably in France. This meant that: “Clandestine workers met employers' needs well. They were a flexible source of labour, and their weak legal status compelled them to accept poor wages and conditions. Once they had jobs, clandestine workers were often regularized by the authorities, which granted them work and residence permits” (Castles, 1986). The importance of Portuguese migration - both by its intensity, and its participation in the industrialization of Europe - is therefore the inverse function of its representation in the scholarship.

The end of the dictatorship (1974), the promulgation of article 44 of the new Portuguese constitution (1976), which guarantees the right to emigrate, the entry of Portugal in the European Community in 1986, and its joining the Schengen space in 1995, have meant that Portuguese can leave and enter freely.2 Yet from the 1970s on, Portuguese migrated less. In the 1980s the return of the ones who left aroused the interest of scholars, who started exploring themes such as the restructuring of rural society (Reis and Nave, 1986; Acheson, 1990; Barros Gonçalves, 2007), impacts on agriculture (Black, 1993), participation in local associations (Rocha Trindade, 1987), architecture (Vilanova et al., 1994) and in general, the relations between origin villages and residency abroad (Charbit et al., 1997; see also Azevedo, Desille, Hily and Pinho, 2022). The pioneering work of Charbit, Hily, and Poinard (1997) is to be replaced in a larger context of complexification of migration patterns, that the origin/destination and emigrant/returnee categories failed to capture. Their concept of “back-and-forth” (va-et-vient in French) participated in the debate on transnationalism (Glick Schiller et al., 1992; Bash, Glick Schiller, and Szanton Blanc, 1994; Faist, 1999; King and Christou, 2011; Carling and Erdal, 2014; Mügge, 2016). Yet this theoretical development has had little impact on how out-migration and return were conceptualised in the Portuguese scholarship (Peixoto et al., 2019; Vidal, 2020). Despite the fact that the transnational activities of Portuguese migrants, associations or the government went hand in hand with new forms of intra-European mobilities, new destinations and new patterns of circulation (Pereira-Ramos, 2005), Portuguese migrations were silenced and stigmatised (dos Santos, 2013). For early-career scholars like myself diving into this developing scholarship, there is a crucial need to think of return in a looser understanding, and as embedded in other mobilities. Making return migration more visible should be done along with other circulations and complexified mobilities in “the global village” (see Milazzo, 2018). This will participate more actively in re-evaluating the true potential of plural forms of displacement/emplacement in places distanced from socio-economic, cultural and political cores.

Between the 1990s and 2005, Portuguese emigration was nearly invisible among politicians and academics (Malheiros, 2011). After 2008, the resurgence of out-migration to cope with the economic crisis (Peixoto et al, 2019) has enabled a renewal of the interest towards return to Portugal, with the notable creation of the Emigration Observatory in 2008, and some academic production. In their analysis of the 2011 census figures, Peixoto et al. (2019) have found that “there were about one million returned emigrants in 2011, i.e. almost 10% of the resident population” (with the statistical omission of returnees who have died and those who have re-emigrated).

The potential contribution of returnees to Portugal socio-economy, recently portrayed as “assets” (Malheiros, 2011), suffers a double discourse. It is true that a positive discourse is brought forward where Portuguese migration is shown as heroic and a-critical (Pereira, 2017). The migrant’s success is self-made. Portuguese that have migrated more recently are expected to fit even more a profile of high-skilled, chosen migration. TV or radio programmes staging these migrants push forward an image of a cosmopolitan Portuguese (da Cunha, 2017). Yet in parallel, Portuguese who have left during the golden age of the guest worker system are defined in Portugal by a lower class, lower education, and irregular migration trajectory (Volovitch-Tavares, 2005; Espirito Santo, 2013); and in the countries where they worked as docile, hardworking, flexible manpower. In the eyes of many Portuguese, the emigrantes are still stigmatised for their lack of education, the way they speak Portuguese, the ostentatious culture illustrated by recent expensive cars, clothes and haircuts, and by the houses (Gonçalves, 1996). The emigrant house, always pictured as tasteless and showy, is a marker of class (see for instance de Villanova [1994]), even though it is the outcome of translocal practices, where the import of construction techniques from abroad distinguish them from others (it is also much rarer in the Montesinho Natural Park, where construction is more controlled (Baia, 2022).

As in other countries with a considerable diaspora (Gamlen et al., 2019), Portugal has started to “court” its migrants. From easy access to citizenship for descendants, to the right to vote abroad, to promotion of re-integration in the labour market, the outreach varies. From 2019, wannabe returnees can benefit from the Return Programme (Programa Regressar in Portuguese), tackled in Pinho et al (2022).3 This programme, the result of an interministerial coordination relying on focal points in different institutions is defined through 5 strategic areas: job offers, education and training and degree equivalence, geographic mobility (returnees get an allowance for transport and settlement), fiscality (a tax discount of 50% of what one should normally pay, for five years), and investment (which consists in a line of credit from the Agency for Competitiveness and Innovation, or Agência para a Competitividade e Inovação in Portuguese). At the institutional level, returnees can also turn to a local helpdesk, Gabinete de Apoio ao Emigrante (GAE). The GAE network is supervised by the Portuguese communities of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Nevertheless, participants to my research had very little knowledge of these mechanisms. This has led me to question the discrepancy between the representation of returnees in the national imaginary, the national policies framed by this imaginary, with actual experiences of migrations. Here again, I reiterate the importance of deconstructing these two contradictory discourses to bring to the fore the actual experiences and practices that dynamize border zones and produce diverse connexions with networks at different levels.

In fact, there is research that has proven the concrete contribution of Portuguese migrants to Portugal rural regions, and borderzones. Silva (1984) has first reflected on the role of returnees in regional development. The edited volume Return Migration and Regional Economic Problems (King, 1986) already comprised a chapter on rural Portugal. Black (1993, p. 565) has argued that return migration can be seen as a “force for change in rural society”. More recent type of investments (real estate, tourism, businesses but also socio-political) of broad return mobilities, as well as the potential of “return of innovation” or “brain gain” for the regions which benefit from return have been looked at in other rural contexts (see for instance in Ireland and in Wales, Farrell, Mahon and McDonagh (2012); Goodwin-Hawkins and Dafydd Jones (2021), and in Portugal, Santos (2021)).

In that context, this piece participates in an actualized account on the impact of return (and other mobilities) on place-making in villages and small towns. It adds up to a still too scarce literature on the recent development of rural Portugal and its migratory layers (Fonseca, 2008; Morén-Alegret, Fatorić, Wladyka, Mas-Palacios, and Fonseca, 2018). And by doing so, it participates in decentering knowledge production related to migration (Flamant, Fourot and Healy, 2020) and including places that are much less often studied for their “links with the wider world”: “we can say that small and mid-sized cities, even much more than big cities, are simultaneously connected to other urban spaces, crossed by flux, influences, but also rooted in history, in heritage. This inclusion and this distancing of the world make small and mid-sized cities complex research objects, at least as sensitive to analyse as very big cities” (Carrier & Demazière, 2012, p. 141). Yet we cannot ignore that more peripheral cities typically lack the tools to “capitalise on the opportunities multilocality presents and the ability to respond to its potential challenges” (Landau, 2018). Landau’s work in municipalities in the south of Africa enables me to understand the embeddedness of Trás-os-Montes villages and small cities with wider networks. Landau redevelops the concept of “archipelagos”, which are “linking cities with sites across rural hinterlands and other urban centres”. As individuals and families resort to multilocality and mobility for socio-economic survival, their movements into, out of and within cities participate in the production of nodes in national and diasporic networks of social and economic exchange.

In the next section, I explain how I apprehend these points methodologically.

Place-making: analysing symbols, social representations and narratives

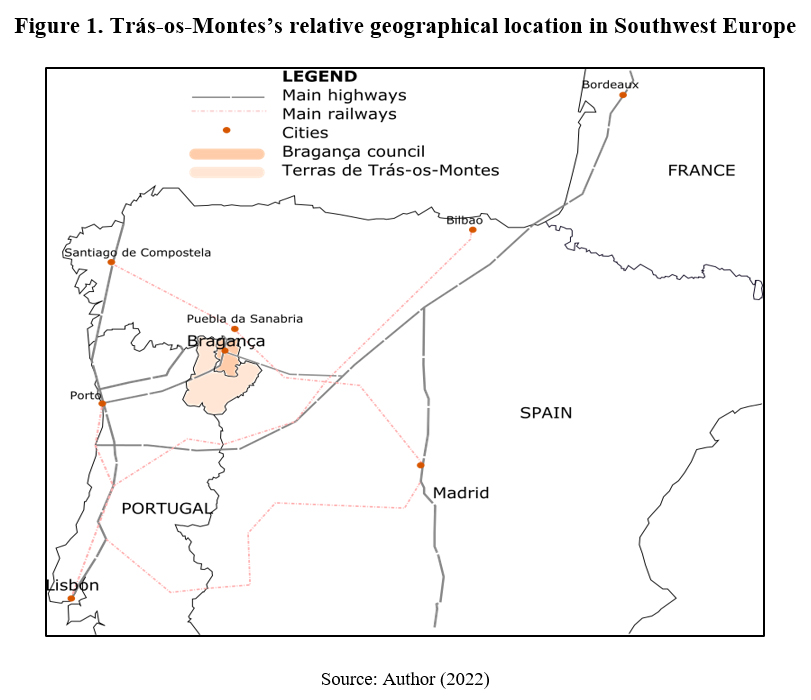

Between 2018 and 2020, I spent time in Bragança, and in three villages located in Bragança council, in the Montesinho National Park in Trás-os-Montes (see figure 1). The city and the villages are located a few kilometres away from the raia, the Hispano-Portuguese border. I stayed the longest periods in the summer, but also visited in the winter, and when there were significant events organised in the region.

During this time, I met with 21 families, whose members have experienced mobilities in Portugal and out. The regularity and intensity of these encounters varied. For some, I have met with several members of the family, and at almost each visit. Some others I met only once. Some, I met only one member, but often enough to have heard stories of other relatives living abroad. At the end of each day in the region, I wrote down notes including our conversations, feelings, impressions, and the places I visited. To preserve the anonymity of participants, I will not make mentions of the village where they live or originate, nor their last name.

Some purists might frown upon the fact that I (deliberately) circulate between the villages and Bragança, mixing the rural settlements with a city of twenty thousand inhabitants. Administratively and politically, the villages are indeed part of Bragança council. Decisions, budget and more are for both types of locales. But mostly, as much as Landau’s archipelagos, the spaces are entangled, even more from the point of view of the villagers. Some of the families I interviewed have real estate both in the village and in Bragança.

A final methodological point: several of these family members participated in the filming of an ethnographic film entitled I am everywhere and nowhere at once (Desille, 2021). Resolving to camera work has given me access to various dimensions of the participants’ lives. They have shown me the houses they lived in, and the refurbishing they did. They have shared what they occupy their summer with: walking or driving in nature, playing, meeting with relatives. They have told me their migration and return stories. And they invited me to follow them during events organised in the summer, such as the Emigrants’ festival (Festa do Emigrante in Portuguese)4 (see figure 4), or the smuggling path trail (Caminhada da Rota do Contrabando in Portuguese)5 (see figure 2). As I have argued elsewhere (Desille, 2018), and based on Doreen Massey’s work (1991, 1999), places are the outcome of the multiple social interactions that cross them, and therefore, of people. The belief that places take shape through human activities has methodological implications. Places are given a set of symbols, social representations and narratives that we can analyse. Hence, these events act as “vignettes”: cultural mechanisms (e.g. ceremonies or rituals) illustrating the relation between society and space (Rogaly & Qureshi, 2013).

Let me now introduce the region where I carried out this fieldwork.

“Bragança is closer to Madrid and Paris than Lisbon!”

The first time I drove past Mirandela towards Vinhais council, it was late afternoon, and it was winter. There were so few lights visible through the windows, so few cars parked in front of the houses of the villages I passed through, and so many signs indicating that the houses were to sell (at least compared to my usual experience of driving through rural areas): I wondered how many of those houses were abandoned. The time to reach the flat I had rented, it was already pitch dark, and the feeling that houses were empty grew bigger. Based on the 2011 general census data, the population of Terras de Trás-os-Montes decreased from 193,072 inhabitants in 1960 to 117,527 in 2011. A new census was conducted in 2021: preliminary results6 show that the 9 councils forming Terras de Trás-os-Montes have lost between 15 to 9% of their inhabitants, except for Bragança council which registered a 2.2% decrease. Four people in ten left the region in fifty years7. Many of them have left clandestinely in the years of the dictatorship.

For the Portuguese state, Trás-os-Montes is a periphery. It is labelled inner territory, or in Portuguese, território do interior. The area is targeted for regional development programmes: for instance the Portuguese national programme for territorial cohesion8 sets goals of equality, and includes Portuguese emigrants as potential entrepreneurs and “ambassadors”. The area is also a receiver of EU subsidies: from Vinhais cultural centre, which I visited and will speak of in a section below; to the many traditional houses turned into rural lodging available for short rent in the area, a lot of cultural and touristic infrastructures benefit from these European transfers.

Yet, the proximity of Bragança to the rest of Europe was often mentioned by the “emigrants”, Portuguese from the region who have left largely during the dictatorship, but also more recently because of a lack of economic opportunities. They assert that the region is closer to Spain and France than Portugal’s capital, Lisbon. As a matter of fact, by car, it takes two hours less to reach Madrid, and four hours less to reach Paris from Bragança. A returnee who operates a taxi in the area often drives passengers to Madrid’s airport, rather than Porto or Lisbon’s airport. For the holidays, many emigrants drive long hours to reach the region, through European highways. The European IC4 actually reaches Bragança and the rest of the northern region of Portugal (see figure 1).

The local economy heavily depends on their “recreational return” (King & Christou, 2011): summer time is the main season where Portuguese from the area, or with family members living in the area, come to visit. When I compare my visits in winter time, to the weeks I spent in the summers of 2019 and 2020, the large number of cars with license plates from France, Germany, the Netherlands among others, and the restaurants and cafes’ full terraces were the most striking. In the villages, children were in sight, while the ones that live there the whole year are few.

As for the emigrants that have returned more permanently, they are crucial to the life of these villages. There is evidence that the local economy depends on them - as shown in the pioneering work of Silva (1984), and more recently by Santos (2021). In the first village I visited in February 2019, among the few houses where lights were turned on, four belonged to recent returnees. I will detail further their contribution to the life of these villages in a section below.

The proximity of the area to Spain is also reflected in the development of tourism in the region, notably from Spain. In the Montesinho Natural Park, a protected area running north of Bragança and Vinhais until the Spanish border, local entrepreneurs running a camping park, and traditional rural lodging, told me that Spaniards make up the larger share of foreign visitors in recent years. In their opinion, proximity as well as the relatively cheap cost of a stay in Portugal are the main reasons for this new trend. Additionally, entrepreneurs I met, and often their staff, could converse in Spanish. Cross-border activities are also in fashion in the area. Visiting the villages of Rio de Onor and Rihonor da Castilla which form an ensemble separated by a now invisible border is an attraction in itself. Hikers can also enjoy smuggling paths and other hiking routes crisscrossing the border (see footnote 4). These trails are reminders of economic and social strategies deployed at a border. Ironically, the accession of Portugal and Spain to the European Community and Schenghen in 1986 and 1995, respectively, has confined cross-border activities to a ‘thing of the past’. Both in the Montesinho Natural Park and in another bordering Natural Park, that of Serra de São Mamede in eastern Portugal, villagers I met have testified of the vacuum left. This is also the theme of Spanish photographer Victorino García Calderón’s photo exhibition “La Raya Rota” (2000), where he displays abandoned buildings and train stations at the Portuguese-Spanish border. Residents of both sides still cross the borders by car, some on a daily basis, for work9 or for groceries or fuelling the car (hence taking advantage of price differential in both countries).

These new developments are backed by an important infrastructure project: In September 2020, the Portuguese government announced the building of a train rail running from Bragança 20 kilometres into Puebla da Sanabria in Spain (see figure 1), supported by EU cohesion funds. The region will be connected to the fast train to Madrid, making Bragança “the closest Portuguese city to Madrid” (Nunes Mateus, 2020). Twenty years after the Tua line closed (in 1991), and with it Bragança’s train station, it seems that the area will be unlocked towards Spain, rather than towards the Portuguese coast.

Re-branding through revisiting historical geographical functions

As the reader understands, the area of Trás-os-Montes, and more particularly the region of Bragança and the Montesinho Natural Park, is fostering an ambiguous relationship with its border: when closed, it was a place of informal exchanges and out-migration. Now that it is open, circulation occurs for work, leisure, groceries, tourism and family visits. But this is not this contemporary reality that is necessarily valued: the now open border is rebranded as a “region of exchanges” through revisiting its past. Nina Glick-Schiller and Ayse Çağlar have worked towards the reinstallation of “downscaled cities” (2010) or “disempowered cities” (2018) in studies linking migration with urban transformations. The term “disempowered cities” appropriately fits this study: “Disempowered cities are those that once boasted greater economic, cultural, or political significance, upon which these cities now strive to build” (2018, p. 92). In both their definitions, these cities also host migrants, and migrants are conceived as city-makers. Despite structural limitations, local leaders of the cities they conduct their research in - Mardin, Halle and Manchester - responded “by embracing a welcoming narrative that cast newcomers and returning minorities10 as crucial to urban development” (ibid, p. 93).

Bragança has entered the network of Jeweries of Portugal (Rede de Judiarias de Portugal in Portuguese), a network of cities and villages with traces of Jewish presence. It is possible to visit the Centro de Interpretação da Cultura Sefardita do Nordeste Transmontano and the Memorial e Centro de Documentação - Bragança Sefardita. The website of the Network of Jeweries of Portugal11 traces the presence of Jews in Bragança’s region to the expulsion of Jews from Spain, and the fact of being a borderzone. In the interpretation centre, an English sign reads: “According to Orlando Ribeiro and Jorge Dias, the northeastern Trás-os-Montes is presented as a border area, a territory where people live, a human geography. It is a region of preservation and transfer of heritage, which shapes a historical-cultural matrix, in which the Jewish presence plays a significant role”. A parallel can be made with another Jewish visitor centre, in Castelo de Vide, in the Serra de São Mamede mentioned earlier. There, the sign reads: “Years ago, in 1492, 4000 Jews who were expelled from Spain, crossed the border of Marvão and took camp in the council. Certainly, the city welcomed many of them among theirs. As much as today it attracts many people from outside...”12. In both cases, the former presence of Jews serves to justify a tradition of openness and welcoming. Yearly, Bragança hosts an event on Sephardic heritage. I attended the second edition in June 2019, entitled Terra(s) de Sefarad. During the event, one of the organisers argued that Trás-os-Montes suffers from “The fate of being a peripheral zone, of being from the interior... something less, as if it will always be like this”13. Then he goes on to explain that during the Sephardic past, Bragança was not a periphery. Bragança was in the centre. Jewish heritage serves the purpose of recentring the narrative, and hence the position of Bragança in a largest European ensemble.

Another displacement is re-written by local institutions: the out-migration of Portuguese during the dictatorship. In 2017, Bragança’s museum Abade de Baçal curated the exhibition “Memories of Salto: Clandestine emigration in the Estado Novo in Trás-os-Montes” (Mémorias do Salto: Emigração clandestina no Estado Novo em Trás-os-Montes in Portuguese)14, that then circulated in various exhibition halls in the area. I attended the opening of the exhibition in Vinhais cultural centre in December 2018. Apart from large format photography, the exhibition adopts multimedia. Emigrants that eventually returned to the region, former smugglers and even police retell the salto in videos the visitors can watch with a small screen and earphones. Visitors can also hop on a belt and walk through the border with a smuggler, helped with virtual reality equipment. Whereas the dictatorship had portrayed them as traitors, in his opening speech, Vinhais mayor praises the emigrants, rebranded as adventurers and free movers (on this issue, see Pereira, 2017). Some months later, Bragança local radio interviewed persons who were involved in smuggling during the Estado Novo too.

I took part in another commemoration of these smuggling activities at the border. In one of the villages I often spent time at, every August, both the Portuguese and Spanish villages facing each other organise a hike: the smuggling path trail (a caminhada da Rota do Contrabando in Portuguese) (see figure 2). Every year, the starting point changes: once in Portugal, once in Spain. The villagers also change the track of the hike, to include different landscapes. In 2019, we were 180 hikers gathered together after dawn. After paying the fees to the village committee, we could enjoy a homemade breakfast, with traditional breads and fried sweets. And we left for the hike. Many of the hikers were emigrants. I recognised five of the 21 families I met during my different stays! After three hours of walking and climbing, we reached the Spanish village, where snacks and hot chocolate were distributed. For the youth, this is a sports event, and they compete to reach the village in the shortest time. The elder hikers shared anecdotes related to their migration, and to the small smuggling activities they were involved with as teenagers. For the organisers, it is a moment of friendship with their neighbouring village.

Source: Film I am everywhere and nowhere at once (Desille, 2021)

Figure 2 The smuggling path trail (a caminhada da rota do contrabando in Portuguese) in August 2019

This new narrative of openness transpires in other initiatives in the region. I met with the mayor of Bragança in January 2019 in Lisbon. He participated in the Caritas-organised event (Pacto Global para as Migrações Ordenadas, Seguras e Regulares - da sua adoção à implementação nacional in Portuguese) During his talk, as a provocation to the slow service of the Foreign and Border Service (Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras, o SEF, in Portuguese) bureau in the capital, he called for people to come to the Bragança branch “where service is much faster than in Lisbon!”. At the break, he told me about different events and projects. Among them, Bragança hosts a yearly event called “Bragança and the International Community” (Bragança e a Comunidade Internacional in Portuguese).15 There is also a plan to host a museum of Lusophone languages and creoles, the Museu da Língua Portuguesa. In 2020, a private firm won the tender for its design. It is true that Trás-os-Montes also hosts speakers of the Mirandese language, spoken in a few villages distributed across the Hispano-Portuguese border.

Yet minority groups currently living in the area are hardly mentioned, or at least, with no agenda to include them in this narrative of openness. As in Cohen and Shemingham’s contact zones (2017), the regional identity draws selectively on the past. Neither the Roma community present (Nicolau (2012) recensed 136 families in Bragança council in 2007), nor the large group of postcolonial immigrants - either immigrants after the 1970s, or students at the local college, originating from Cape Verde and São Tomé e Príncipe. On the contrary, while interviewing agents in local real estate agencies regarding investments made by emigrants in Bragança, some affirmed that they refused to rent these assets to African students, evoquing issues of guarantees. But this is not the issue addressed in this paper. Rather, let me come back to the emigrants and returnees.

Stereotypes and shame: marginalising Portuguese emigrants from a narrative of openness

I have shown that historical displacements are the target of rebranding for touristic and economic purposes. As for contemporary migration, in Trás-os-Montes, the current migration trends that are predominantly mentioned are the out-migration of youth - still ongoing in a region with little employment opportunities - and the return of emigrants. As a matter of fact, 2011 census data regarding residency (and not migration) shows that the traditional areas of out-migration (Minho, Beira and Trás-os-Montes) are the ones with the highest percentage of new residents (that is persons who moved to Portugal in the last ten years). This goes against the common belief that Lisbon and Algarve are the main receivers of new residents. And about half of them had a former residency in France. In Trás-os-Montes, 41% of the total of former foreign residents used to live in France. And most probably, they were born in Portugal. This goes against the idea that rural areas are not areas of return anymore.

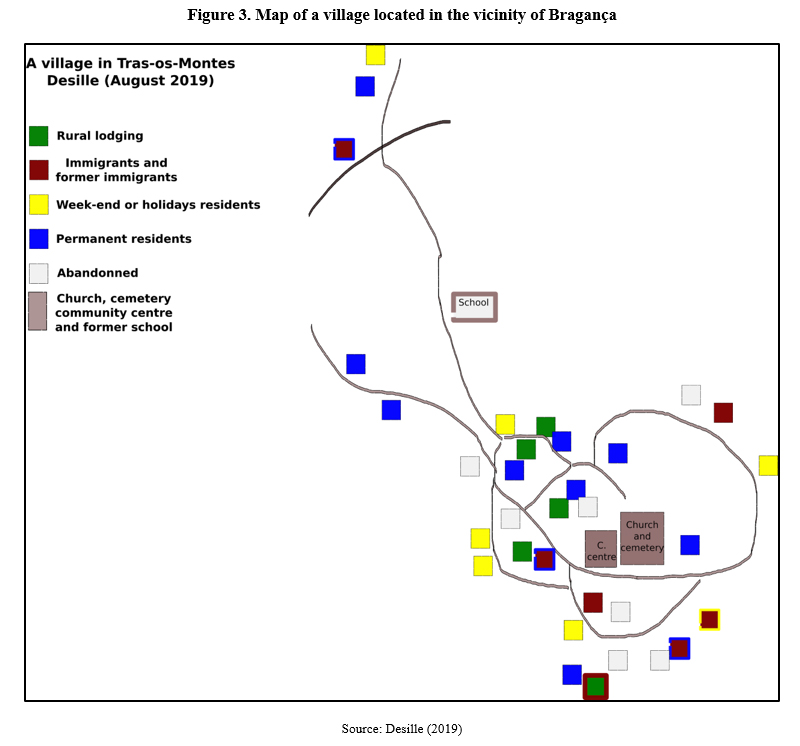

Let’s look at this village, located in the vicinity of Bragança:

This is the situation of the village in the summer of 2019. The village counts 33 houses, a church, a cemetery, a community centre, and the building of the abandoned municipal school. 12 houses (in royal blue) are occupied all year long, while 14 are sometimes occupied by non-residents: emigrants who return for short visits, week-end or holiday residents, or tourists. Seven houses are abandoned. Seven houses are owned by people who have experienced migration (brown houses): three of the permanent residents are former migrants who have permanently returned (from France, Germany and Spain), one migrant family owns a rural lodging, two own a house that they use for their visits, one lives in a city nearby and comes for the week-end or holidays. Among the 12 permanent residents, five are retirees, two work in agriculture while five work outside of the village, in factory or public work. All factory work is related to one big investor and its outsourcing: Faurencia, a French automobile group. As for public work, it is actually care and cleaning work for public institutions. The seven commuters (yellow houses) come to the village for lifestyle reasons: they have refurbished family houses for their personal use during week-ends or holidays. The rural lodging is a source of activity but also of complaint for permanent residents. Four of the five houses belong to a local elite from the neighbouring city of Bragança or from Porto who knows about EU subsidies and got support to refurbish the houses. They should commit to renting the houses, yet two houses are not open to tourism at the moment of fieldwork. This provokes resentment from some of the families who did not have the means to turn old houses for tourism, and got the opportunity taken away by outsiders, better connected to the municipality.

One can see that the village is embedded in regional, national and international networks. The resources needed to maintain the village houses sometimes come from remittances or EU funds. I was even shown objects in the houses which come from life in migration (see also Azevedo (2020) on this matter). Residents circulate or have circulated between the village, other houses in Portugal, and outside (Spain, France, Netherlands, Germany and Guinea Bissau16). For work, but also simple activities such as visits to the doctor, grocery shopping… residents must go to nearby Bragança. Several of them do not own a car, and rely on the three daily buses operated by the regional council. Food trucks also visit every week selling bread, meat, or groceries. There is one child in the village during the year, who goes to school in Bragança.

Despite this example (and other villages I spent time at displayed similar embeddedness), and apart from memorial narratives of the salto and other smuggling activities, emigrants and returnees in the villages do not participate in the narrative of openness I described earlier. As Pereira (2017) has noted: “Transforming emigrants in heroes permits to not face a past - and a present - that the majority of Portuguese elites would rather forget”17. Although I thought the shame accompanying emigrants of the time of the dictatorship was confined to the post 1980s period, participants living in the area - even some that did migrate themselves - continue mocking the emigrants and the returnees. Emigrants, in the words of one informant, are “wiping the Frenchmen’ bottoms”, working in care or cleaning jobs.

Returnees are also often portrayed as non-productive people, who come back after retirement. But statistics on the age structure of returning emigrants show that a majority are of working age (Peixoto at al., 2019). Half of emigrants from traditional destinations (France, Germany and US) are indeed retired. But this is not the case when taking into account new destinations. Additionally, all the said retirees I met, work. They are involved in agriculture: several own chestnuts, extensive gardens and even small cattle. They are also very much involved in care, often beyond borders: they care for grand-children during the holidays, but also for other relatives. They are in the village committees and take part in the administration of collective lands (baldios in Portuguese), in organising events and so forth. Among the persons that have very recently retired (sometimes before the legal age of retirement), one owns a taxi, others rent apartments they own, and another is an investor in a marketplace for farmers, selling products but also services. Not all are retirees either. In the area under study, three French-Portuguese households in their 30s came back to set a restaurant, a construction company or a garage. One manages a rural lodging, as shown on the map. As Rossana Santos has shown in a recent study (2021), returnees do take part in rural tourism development in Portugal, either directly by setting tourism-oriented businesses, or indirectly by participating in maintaining rural landscapes.

Many emigrants still live abroad, but visit the area often. The restrictions of circulation adopted during the sanitary crisis in 2020 triggered fear among business owners for whom the absence of emigrants would be catastrophic. Business owners wait for the summer.18 In villages, reminiscences of emigrants’ festivals, including the walk I took part of (Desille, 2019), are important events. But they are not seen as a target by the local institutions. A case in point: in 2019, in Bragança, it was the first time that the Emigrants’ Festival (see footnote 3) was organised. The organising association asked the municipality for support, and got permission to use a space. Which the municipality forgot about. Two weeks before the festival, the association enquired whereas all authorisations were fine, to realise that they were forgotten about! Eventually, some days before the event, all was sorted and the festival took place.

Source: Film I am everywhere and nowhere at once (Desille, 2021)

Figure 4 The first edition of the Emigrants’ Festival of Bragança, August 2019

National programmes versus local realities

I first assumed that the municipality of Bragança, which serves the nearby villages too, was aware of the potential of emigrants who wished to return permanently, hence the creation of a municipal department to support returnees (Gabinete de Apoio ao Emigrante in Portuguese, from now GAE)19. I decided to interview the GAE representative in Bragança. During our meeting, already a year after the GAE in Bragança was functioning, he confesses that three people turned to him. I asked the participants to my research if they knew about the GAE. As it turns out, people deal with their return privately, hire notaries to move their rights across borders, and invest their own money. The municipal agent is mostly dedicated to his first function, economic and tourism development. Will things change in the near future? On 23 July 2020, the State Secretary for Portuguese Communities, Berta Nunes, announced that the National Programme for the Support of Diaspora Investment (Programa Nacional de Apoio ao Investimento da Diáspora in Portuguese) was approved by the Government. In August 2020, Nunes also announced a new reform regarding GAE20. The goal is to enlarge the network from the 180 existing GAE to reach 308 municipal councils. Information regarding the National Programme for the Support of Diaspora Investment will also be made available, expanding the responsibilities of GAE to diaspora investment.

As for the Programa Regressar mentioned in an earlier section, none of the people I met in Trás-os-Montes thought of this programme. A participant to the research lives in one of the villages around Bragança, with one of her children, while her partner lives in the Netherlands, and her other child in the UK. She told me she wished her partner would be able to come back before retirement, and I gave her the flyer on the Return Programme given to me at the municipality. But it did not look practical for her at all. It is designed for people who already have a job, or the means to invest. As a matter of fact, at the moment of our conversation in 2019, the programme provided that the person must sign a permanent contract, or open their business. Both these options hardly fit the profile of the relatives of the family members I met. At the workshop I mentioned earlier, a representative of the Institute of Employment and Professional Training (Instituto do Emprego e Formação Profissional in Portuguese) confesses that the credit line now open fits less small businesses (such as hairdresser, garage…), and this should be adapted. In January 2021, the Government amended once more the programme: returnees can show that they have signed a contract for at least six months, returnees who mean to set up a company or will be self-employed can now apply to the programme too, and receive benefits (for changes of this policy, see Pinho et al. (2022)). Returnees settling in the periphery are entitled to a slightly higher support. And according to the statistics of the programme, 1 in 8 returnees benefiting from the allowances settle in the inner territories.

Discussion and conclusions

There is evidence from the field that the border zone of Trás-os-Montes is indeed a contact zone. The sketch of the village shows the extent to which movements and sedentarism coexist. Multiple mobilities, from out-migration to return, lifestyle commuters, foreign and Portuguese visitors; as well as the fact that economic life does not rely on traditional rural occupation, testify to the fact that the village is resolutely turned to the outside. Widening the collection of qualitative data in different border zones, beyond Portugal, could inform better intra-EU migration policies, and participate in less national-bounded initiatives. Another village, the one where the hike takes place yearly, emphasises its relation to Spain as well as migration and return as the main socio-cultural events and identity markers. Place-making occurs through the actual movements of people, the objects they bring, the skills too (such as construction skills). This leaves material traces: new and old buildings, notable renovations, maintenance of fields and gardens. But place-making also happens with the narratives: the smuggling memories, the migration experience, and the current transnational lives of the families and the anecdotes they tell around these multisited lives.

These in turn are tapped into when it comes to organise exhibitions, to inform radio programmes, to participate in the leisure offer of the area. One can see the efforts of the local leadership to relate to the “extroverted” identities of the place, and to deal with the situation of disempowerment by conjuring memories of openness belonging to an idealised past. Yet I argue that this recognition is limited to selected events. Trás-os-Montes’ Sephardic identity is well exploited. It can be because a network already exists and coordination with public and private efforts is already on-going. In 2020, the national newspaper Público published several articles on Jewish tourism and Israeli immigration, calling for renewed efforts to attract these visitors - “a public with a cultural level above average, with cultural interest valuing our heritage, and with a purchasing power above the average tourist” (Mendes Pinto, 2020). It can also be that the Jewish presence corresponds to the “golden age” of Bragança, in the Middle Age, where the region was indeed at the centre of the new kingdoms in formation, strategically situated between Castilla y León and Portugal. The institutional focus is on past rather than present movements. And on tourism, rather than tapping into mobility and multilocality, as Landau suggested. It may be that the amendments introduced by Nunes, such as the inclusion of diaspora investments along with return support, will operate a change. But the low engagement of the current GAE in Bragança hints to the contrary. This finding corroborates other research conducted in Eastern Europe where there seems to be quite some resistance against including contemporary movements of people in rebranding plans, while historical mobilities and past porosity of the border is staged uncritically (Caglar, 2013; Pogonyi, 2015; Cingolani and Vietti, 2019).

In general, there is a resistance to take into account contemporary migration movements that contribute to place-making. From the central administration’s point of view, despite recent infrastructural efforts, Trás-os-Montes is a periphery rather than an interface with the rest of Europe, as its geographical location suggests. The perpetuation of this peripheral identity is illustrated by the drafting of a large interministerial programme that does not take into account the reality of return migration, but insist on targeting returnees from very recent out-migration waves - following the 2008 economic crisis, and the austerity policies put in place from 2011 - with very exclusive contracting conditions or the means to invest. A certain narrative of cosmopolitanism and success linked to young, educated recent emigrants, persists which do not reflect the migration experience of many candidates for return originating from traditional out-migration areas, including Trás-os-Montes. And they are only one of the migrant groups that are not receiving the attention of the national, regional or local institutions.