Introduction

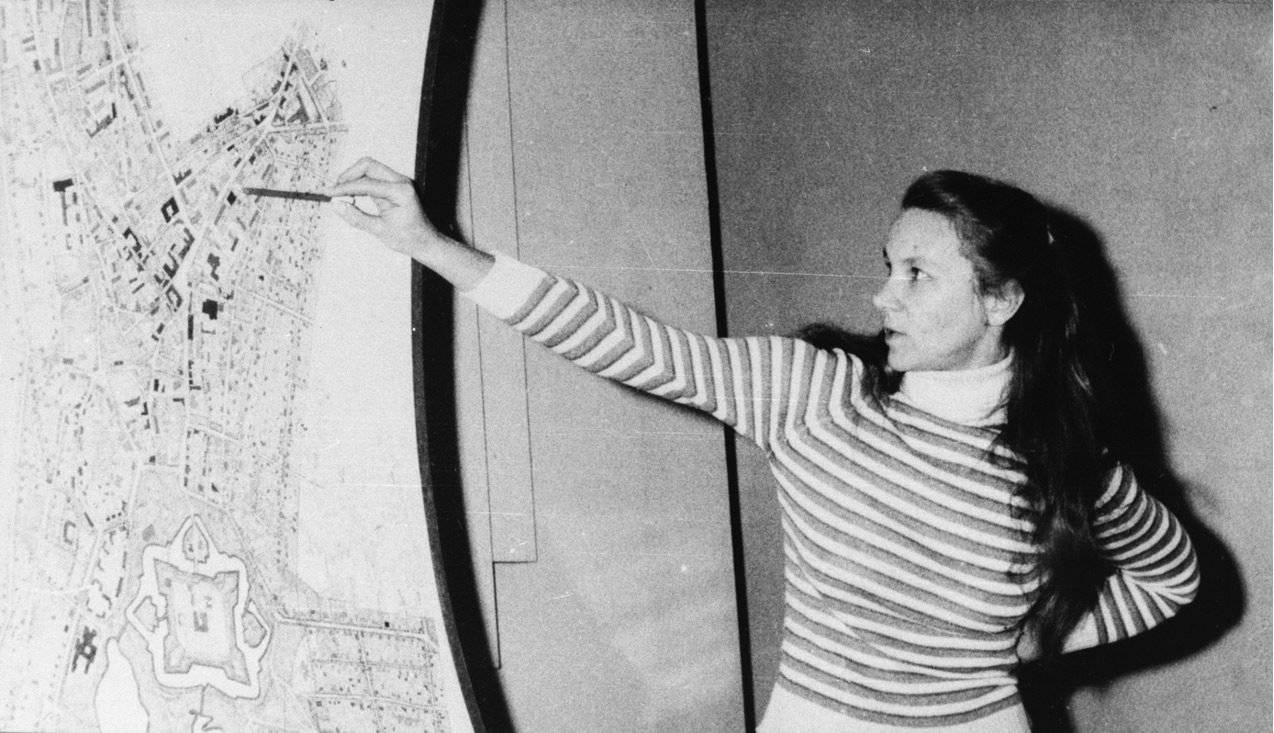

It is common knowledge that there has been, and to an extent still is, a firm glass ceiling in the architecture profession. However, every rule has its exceptions, and the context of Soviet Estonia with its official policies of women’s emancipation has provided a favourable seedbed for such exceptions. The current article is focused on four outstanding Estonian women architects, two from the Soviet and two from the post-Soviet period, whose careers advanced to the top positions in their field: Lilian Hansar (Figure 1) and Irina Raud (Figure 2) were appointed city architects, and Margit Mutso (Figure 3) and Katrin Koov (Figure 4) served as presidents of the Union of Estonian Architects. While there certainly have been other women architects with outstanding creative and administrative output in the field, those four were chosen because their careers advanced to significant power positions - Mutso and Koov have been the only female leaders of the UEA during its 100 years of history, while Hansar and Raud were among the very few female city architects until today - and the relatively ample media coverage their work has received over the years. Based on my own interviews and media reflection, I’m interested in how they perceive themselves as professional women, what kind of creative and career goals they have tried to achieve, but also if and how does their self-image differ from their representation in the media. I believe comparing the career paths and self-perception of those four architects illuminates the problems and difficulties in establishing oneself as an architect in a still masculine-dominated field, at the same time pointing out the changes in professional women’s career opportunities, self-perception and social reception of their activities that have taken place over the transition from Soviet to Post-Soviet era.

The biographical perspective continues to fulfil a major role in mending the gaps in male-centred architecture history and contemporary discourse within the framework of the fourth-wave feminism (Lange and Pérez-Moreno, 2020). Yet it is increasingly acknowledged that such contributions should aim at beyond merely increasing the visibility of women practitioners but should also address more general questions like transnational and geographical aspects of the canon, or the contexts of women architects’ pursuits as determined by networks of influence, professional regulations or informal aspects of organization of the field. The mainstream narrative of Western feminist activism should be measured against a more global perspective that would reveal the local specificities of gender systems and the inconsistencies of standard models, helping to produce a more ‘plural’ feminist architecture history (Burns and Brown, 2020). In this respect, biographical writing should be used strategically - mere adding of new names and exceptional works of architecture to the existing canon would fail to challenge the default assumptions of constructing the canon. Instead, biographical writing, contributing to linking contemporary activism to historical genealogy, should simultaneously interrogate the conditions of subjectivity production in the context of architecture. In this sense, oral history could prove a fruitful tool with an activist potential, able to produce ‘counter-memories’ outside the high-profile circuit of the Western canon (Burns, 2019). Dovetailing with the larger cultural trend of personal histories and storytelling, oral histories are motivated by a desire for ‘the real history’ but at the same time display an activist and political engagement, empowering hitherto marginalised groups, creating meaningful connections over the generations, and creating communal bond with the public. In the context of feminist architectural research, oral histories help to make visible the position of women in the collective memory of local architecture discourse and establish the lineage preceding the contemporary practitioners. In architecture, employing oral histories also helps to balance the traditionally elitist discourse by broadening the range of agents whose contribution is noticed and who are seen as entitled to discuss the matters (Stead, van der Plaat and Gosseye, 2019). While it must be acknowledged that oral histories always involve a retrospective aspect and the interviewer’s subjectivity is also involved in the narratives thus created (Abrams 2010), the affective potential of those narratives works in an empowering and inspiring way.

The current article is based on in-depth interviews that I conducted with the protagonists in Autumn 2018 as part of the preparatory process of an exhibition A Room of One’s Own. Feminist’s Questions to Architecture (2019) at the Estonian Museum of Architecture1. The interviews, ranging from an hour to an hour and a half, were, in a much shortened and edited form, used for a film displayed at the exhibition, featuring 15 Estonian women architects from different generations2. Thus the interviewees were aware that their testimonies could be used for public display. The choice of the architects resulted from the aim to encompass a wide range of generations and experiences: of the 15 interviewees, the oldest was 92 and the youngest 33 years old, and their practices involved both urban planning as well as architectural, interior and landscape design. There was an open set of questions concerning their experiences with architecture studies, conditions of setting up a career, family background, work and life balance, and reception of their work. The other source of the article has been portrait stories of these architects in Estonian media - all four have been featured in long interviews or personal portrait stories in mainstream or cultural weeklies, TV broadcasts or women’s magazines. The media content analysed was very varied, ranging from op-ed articles of the architects themselves to interviews in professional media to portrait stories in women’s magazines, at times more reflecting the architects’ own agency and at some instances more resulting in the magazines’ initiative. Also, the general situation and context of media production has obviously changed over the decades with significant differences in terms of journalism conventions of the Soviet and the post-Soviet era. This admittedly adds a certain subjectivity to the sources; however, as the protagonists get to check the article before printing even in the mainstream media and women’s magazines, I believe all the cited sources may be approached as conscious and consented self-representation. The combination and juxtaposition of these different types of sources enables us to analyse the professional position, self-perception and public image of high-achieving women architects on the background of changing social and political contexts.

Women in Soviet and post-Soviet Estonian architecture

In the pre-World War II Estonian Republic, the field of architecture was dominated by men, with only two women, Erika Nõva and Salme Liiver-Vahter, graduating as architects from the Tallinn Higher Technical School, and Paula Ilves-Delacherie getting her diploma from Budapest Royal Technical University. With Estonia incorporated into the Soviet Union in 1940, Soviet emancipation politics encouraged women to study all technical disciplines including architecture. Of course, officially the Soviet ideology was treasuring women’s emancipation and gender equality in all fields and aspects of life. The idea of the equality of the sexes had been an important aspect of the social reformation from the early days of the Soviet state, shaping its constitution and social practices. This was especially the case since the 1930s, following the launch of large-scale industrialization, when the state needed women as members of the workforce as much as for their reproductive capabilities. The ideal of the new Soviet woman was partially formulated on the basis of earlier demands from the women’s movement: women’s suffrage, rights to work, education and participation in social life, and economic independence that would free women from being subjected to men in patriarchal society and family. However, since the Stalinist period the politics of gender was increasingly characterized by two opposing tendencies. On the one hand, it propagated the mass inclusion of women in industrial production and social activities which contributed towards changes in women’s roles and the social attitudes towards them. Still, long held prejudices against working women and sex discrimination in the workplace did not disappear, and there clearly existed a glass ceiling which women workers in industry and women white-collar employees found difficult to move beyond. Training and promotion took them so far, but rarely to the top (Ilic, 2018). On the other hand, patriarchal power relations and conservative gender roles were maintained in the private sphere and the paternalist state strengthened its control over family life and reproduction. Officially, the 1936 Soviet constitution had guaranteed women’s equal rights in all areas of economic, state, cultural, social and political life and thus the women’s question in the Soviet Union was declared solved. The issues of women’s roles and rights were no longer objects of political debate, remaining merely obligatory slogans of state propaganda; and discussions about women’s rights and interests gradually disappeared from political discourse and social studies. The expectations set to a woman thus included both the ability to participate in industrial and agricultural work as well as the more traditional roles in raising and educating future citizens. At the same time, with the thaw and modernization of the 1960s the image of the Soviet woman gradually began to take on also certain Westernized characteristics (Kivimaa, 2010). Thus, in reality, the Soviet woman was a highly ambivalent construct - heroic in the workplace yet motherly at home, ideologically knowledgeable in the social sphere but fulfilling the traditional role expectations in family sphere.

Still, from the 1950s already, the numbers of female students in higher education began to grow rapidly, a process which, among other reasons, was made possible by the introduction of free higher education. Thus, throughout the Soviet years from the 1950s to the 1980s, the numbers of male and female architecture students at the Tallinn Polytechnic Institute and the State Institute of the Arts were practically equal, with women slightly even dominating in the 1970s (Kalm, 2014)3. The percentage of female students was even higher in the department of interior architecture, opened at the State Institute of Arts in 1959. Official encouragement of women to enrol in technical disciplines was characteristic in the whole socialist bloc of Eastern Europe, with different state support measures in place such as the creation of all-women classes with special schedules for seminars and exams to accommodate students with small children, or nurseries in student dormitories (Engler, 2017). As a result, the numbers of women studying architecture soared. Another widespread feature of the socialist bloc that made the situation for women practitioners significantly different from their Western counterparts was the central system of job placement. According to socialist economic model of central planning, the field of architecture and urban planning was organized into quite large state design offices, and private practice was (depending on the country) making up just a minor part of the design profession if not deemed outright illegal. Recent university graduates were officially assigned a professional position in these design offices which meant that soon women made up a significant proportion - up to half of the employees (Marciniak, 2017, p. 65; Lohmann, 2017, p. 178). At the same time it also meant that entry into the labour force was not a matter of free will but a constitutional obligation for both sexes; and the location or position of the assignment - hence also the projects to work on - were generally not for oneself to choose. This situation meant that women architects were active at a very broad range of typologies and tasks. From the 1950s to 1980s, a number of highly original and prolific women architects were practicing in the state design offices, the most well-known being Valve Pormeister, an inspiration for a whole generation with her organic modernism, but also Meeli Truu, Ell Väärtnõu, Marika Lõoke, Eva Hirvesoo, Miia Masso, Malle Meelak and many others, designing modern and postmodern housing, educational facilities, recreational complexes, hospitals but also administrative and public buildings (Ruudi, 2017). Nevertheless, women rarely rose to key leadership positions in the field in any of the countries of the Eastern bloc (Pepchinski and Simon, 2017).

The transition to the post-Soviet period initially saw a decline of women studying architecture (Kalm, 2014) - the social and cultural desire to go back to the pre-Soviet social norms brought along an idealization of traditional gender roles (Kurvinen, 2008). But the backlash at the end of the 1980s was brief and in the last decades female students have steadily made up at least a half if not more in the architecture faculty. At the same time, the organization of practice has undergone profound changes. With the end of the Soviet Union, large state design organizations dissolved, and architects established private practices - a transformation that has required adding competences of entrepreneurship to design skills. The majority of architecture practices in Estonia are small, comprising of a handful of partners plus a small and fluctuating number of employers. In this situation, a common choice for women architects has been to establish a practice together with her husband - a widespread pattern long established in Western context (Colomina, 1999), although there have also been a couple of attempts at women-only practices4. However, in spite of the majority of Estonian contemporary women architects claiming that they do not perceive active discrimination in the field (Mutso, 2019), it is a sore fact that although at 76,3%, Estonia has one of the highest employment rates of women in the EU, its gender wage gap is in the top three among all high-income countries in the world (25,2% in 2017) (Unt et al., 2020). A glass ceiling definitely exists, and it is most prominent among the top professionals. A subjective look at the Estonian contemporary architecture scene seems to confirm: with notable yet quite limited exceptions, the field is still dominated by men.

Lilian Hansar, chief architect of Saare county (1979-1994) and city architect of Kuressaare (1994-2003)

Lilian Hansar (figure 1), currently professor emeritus of the Estonian Academy of Arts, is probably the most highly decorated woman architect in Estonia: her contribution to the development of Kuressaare city planning and architecture as well as general heritage protection policies have been acknowledged with the national cultural award of Soviet Estonia in 1982, Alar Kotli architecture prize in 1988, annual award of the Estonian Cultural Endowment in 2003, and the presidential Order of the White Star in 2006. After graduating as an architect in 1975 she specialised in heritage conservation and reconstruction projects of historical buildings. After five years of practice she went on to become the county architect of her native island Saaremaa, serving there for fifteen years and continuing after that as the city architect of Kuressaare, the capital of Saaremaa. Her tenure in Saaremaa coincided with a fresh wave of postmodern ideas in urban planning which Hansar was eager to apply and develop to counter the preceding Soviet modernist policies. Based on thorough research and implemented with consistency and serenity, Hansar’s architecture and urban policies fostered a contextual approach based on human scale and respect for historical environment. She managed to ban type-designed mass housing from Kuressaare historical centre, and later instituted a requirement of architectural competition for any new building added to the central heritage area. Highly valuing cooperation and peer support, she was also one of the initiators of semi-formal seminar series and meetings discussing the future developments of small towns and rural settlements, and issues of contextual architecture in general. In the 1970s-1980s, rural and semi-urban architecture was by no means a minor field of self-realization - under the bureaucratic planning and restricted creative opportunities in major Estonian cities, architectural innovation tended to take place in the more marginal contexts, supported by a semi-independent system consisting of kolkhozes as clients and builders and a special design office for kolkhoz building (EKE Projekt) (Kurg, 2019; Ruudi, 2017). The unprecedented phenomenon of Soviet Estonian rural architecture with its undertones addressing local and national identity was perceived as an important foothold for resistance to Soviet homogenization.

In 2003, Lilian Hansar was the subject of a half-hour portrait documentary at the Estonian National Broadcast (ETV) dedicated to her long career in steering the architectural developments in Saaremaa.5 The camera follows her from a meeting room, firmly negotiating over a new addition to historical street, to a construction site, commanding the builders to substitute an existing finish with a more delicate, contextual paint; later she is interviewed in her office, explaining her design philosophy and working methods. To a large extent, the documentary builds upon media representation that Hansar had already established with opinion articles and interviews of the previous decades of her working life - that of an energetic, rigorous and extraordinarily uncompromised architect, with media coverage predominantly stressing the masculine qualities of her professional presence (Rihvik 1980; Tammer, 1988). Throughout the articles and the documentary, Hansar is presented as a thorough and level-headed leader with firm ethical and design principles; additionally, in the film the commentators and colleagues stress her ability to integrate theory and practice, and her deep interest in the more general, philosophical aspects of architecture not so common among architects working in bureaucratic positions. As the impetus for producing such a documentary was most likely her receiving of the award of the Cultural Endowment the same year, the overall tone of the production is inevitably celebratory and dignifying. The documentary primarily focuses on her professional image and activities over the years, and does not much distinguish between the working circumstances of Soviet and post-Soviet eras. However, a hint of private life is brought in by introducing Hansar’s activities as a violinist in a popular folk group in her youth, and recalling her school-time dream of becoming an orchestra conductor which she abandoned on the grounds that this was not an occupation for a woman - all conductors she knew were male. While during the whole documentary a very calm, rational and professional approach prevails, the ending brings a surprisingly emotional twist where Hansar is shown practicing flamenco in a dancing group, giving an impressive performance as a self-confident woman in her fifties.

Yet regardless of her fruitful career and notable acknowledgements, in an interview conducted in 2018, Hansar tended to downplay her achievements in a way that has been quite characteristic for women architects on the both sides of the East-West divide (Scott Brown, 1989). She attributed her career choices - heritage conservation and bureaucratic work over architectural design - to believing that her talents as an innovative designer were limited, a stance she admits was ingrained during her architecture studies where the all-male professorship used to direct patronising and condescending comments toward female students (Hansar, 2018). She recalled male professors of the 1970s openly stating that spatial geometry was naturally beyond a woman’s comprehension, and witnessing an unofficial system of pre-selection during studies to single out the most promising male graduates to be assigned a job at the most creative EKE Projekt design office (Oma tuba, 2019). At the same time, she seems to have internalized such masculinist beliefs, pondering that there could indeed be a difference between male and female types of creativity, with men more capable in producing striking, innovative pieces of design that stand out while women were more able to provide contextual additions adapting to their environment. She also admits that through the years, male architects have always been more vigorous at promoting their creative achievements while women see their work as an element in a flux of different contributions over time and space. On this background, she repeatedly emphasised that the primary drive in her career has been a mission for a better environment, a sense of obligation and responsibility rather than ego-driven career ambitions. Concerning the issue of establishing oneself as a woman architect and leader, Hansar admitted to having encountered a lot of prejudices, but she also said that she acquired the positions of responsibility and leadership at such an early age that she was, perhaps, too naive to be afraid. She described the first years full of tough encounters with all-male officials in the municipality and the communist party system, not taking her seriously; but also a feeling of solidarity with the few other women who were working in other municipalities, offering support and advice, including the classic “let your male superiors think that the idea was theirs”. Naturally, the aspect of work-life balance was raised, with Hansar admitting the long hours inherent to the architecture profession regardless of the social and political order, and the toll it takes on one’s private life. In general, the interview with Lilian Hansar painted a picture of a steadfast and meticulous woman, profoundly devoted to her professional calling who has earned respect due to her persistence and ability for hard work but who paradoxically nevertheless supports traditional gender roles and who would have perhaps, under different circumstances, resorted to a less demanding career. However, comparing the ‘official’ respectful and celebratory representation of Lilian Hansar to her ‘unofficial’ testimony of professional hardships, hesitations and weaknesses reveals the internal contradictions often characteristic of a high-achieving professional woman of the late Soviet era.

Irina Raud, Tallinn city architect and vice mayor (1990-1992)

Irina Raud (figure 2) got her career going with a winning design at the competition for Ugala theatre in Viljandi right at the time of her graduation in 1969, and although the design and construction process took more than ten years, it established her as one of the most remarkable young architects. Working at the biggest state design office Eesti Projekt, she mainly dealt with urban planning, advancing steadily from the position of architect to senior architect to group leader and department leader. In tune with the Postmodern shift, she was among the main advocates of challenging the rigidly rationalist planning principles of Soviet modernism and integrating the new interventions with the already existing urban structure. Thus she was one of the main authors of the detailed planning of central Tallinn (1983, together with Ignar Fjuk, Tiina Nigul, Rein Hansberg and Ene Aurik), a scheme that, for the first time, paid respect to the end of the 19th century industrial architecture that was hitherto deemed for demolishing. She introduced the practice of conducting thorough research of demographic situation and mapping of existing buildings and greenery prior to starting a detailed planning process, and her several planning projects for Tallinn residential districts tried to adapt new housing blocks to the already existing historical architecture. In 1987 she was elected Estonian representative to the all-Soviet conference of creative unions in Moscow and surprised this stagnated format with a speech harshly criticizing Soviet construction policies - a sign of a certain liberalization coming with the reforms of Gorbachev but still conducted in such a direct matter-of-fact language unheard of in such a context. In 1990, she was Soviet representative at the congress of the International Union of Architects (UIA) at Montreal, voicing a demand of a separate Baltic representation at the UIA at a time when the Baltic states were still part of the Soviet Union. A year later, she organized an exhibition of future visions for Tallinn at the urban planning exhibition Salon International d’Architecture in Milan. Irina Raud was also the initiator of Nordic-Baltic Architecture Triennial, an ambitious international event that took place every three years in Tallinn from 1990 to 2005, greatly contributing to Estonian reintegration to international professional networks of architecture. In the post-Soviet era, after stepping down as a city architect, she established a private practice that has received numerous major commissions in urban planning and architectural design.

Raud’s appointment to the position of city architect and vice mayor took place at the height of the transition when Estonia was officially still part of the Soviet Union but it was already inevitable that major social and political changes were underway. The short period she was holding the position brought a number of interviews and opinion articles in the media, signifying great expectations that were put upon her but also her own agency in actively reshaping the planning practices. Already the titles of those articles convey the message of renewal and a departure from the earlier bureaucratic and anonymous planning practice: “Are we still planning for an anonymous human unit?” (Raud, 1987); “Lack of resources does not have to mean ignorance” (Raud, 1990); “Mass housing construction will end, we are realigning to the provision of private homes” (Raud, 1991); “We start by amending the previous mistakes” (Käesel, 1991). Concluding from those sources, the clear task she set to herself was to conduct a decisive change in architecture and planning policies, moving from rigid and quantitative top-down approach of the Soviet times towards strategic planning with further foresight that would enable engaging private capital once the political situation allowed (Käesel, 1991). At the same time she advocated a more considerate approach towards already existing historical environments, and engaging the heritage and landscape specialists to the planning process. In tune with the general social changes, she supported greater opportunities for private building and ending the growth of homogeneous mass-produced housing areas (Tänavsuu, 1991). One of her aims was also to bring more openness to the planning processes that during the Soviet times had been quite bureaucratic and opaque, thus she initiated briefings for journalists and other interested parties, an important signifier of a more democratic approach during these transitional times (Harjo, 1990). These were major and significant goals that helped to steer the principles of urban planning towards a more open and inclusive approach, even if she did not have the opportunity to really fulfil them due to stepping down after two years, due to political intrigues concerning the mayor of Tallinn.

However, when I was inquiring in the 2018 interview about the main factors that contributed to her success, and about accomplishing her goals as a woman architect, Irina decisively rejected the suggestion of calling her a feminist. Although seemingly paradoxical, such a stance was widespread among the high-achieving women of her generation throughout the socialist bloc who felt deep ambivalence towards the label and perceived emancipation as yet another directive forced upon them by the state (Moravčikova, 2017, p. 49). A need to dissociate oneself from official Soviet ideology to support cultural and personal identity that would be based on resistance hindered appreciating the more empowering aspects of a feminist agenda. Instead, Raud firmly believed that her success was due to personal talent and staunch work ethics, and claimed that she had not felt any kind of open gender-based discrimination. At the same time, failing to see the inconsistency of her position, she admitted that at the beginning of her career there was a lot of patronizing from male colleagues and superiors. She recalled that in the 1970s, opinions were voiced that she and Inga Orav should not get the commission for designing Ugala theatre in spite of the competition win because they were young women and would most likely soon go to maternity leave anyway. When the commission was finally secured, an older male colleague was added to the design team to “supervise” them; however, Raud admits that, considering the situation, he was a “gentleman” and did not interfere with design decisions. Later in life, Raud recalled being often the only woman among men at numerous design briefings, urban planning and policy-making meetings, or official delegations at conferences and congresses, and never having felt that the attitude was different towards her because of her gender. At the same time, the reality could have included situations towards which women trained themselves to become wilfully blind. For instance, a TV broadcast Arhitekt (The Architect, 1986) had eight top Estonian architects discussing the matters of urban futures with Irina Raud being the only woman around the table, being paid equal respect. Yet at one point, a cake in the form of a recently completed high-rise hotel is brought in, and naturally, of all the crowd it is Irina as the only woman who stands up and starts cutting and serving the cake to her male colleagues, switching effortlessly from the role of an equal professional partner to a woman of service, probably without even noticing the switch herself.

Internalizing certain masculinist values of architecture profession has, in her case, definitely also meant glorification of effort and taking pride in her personal ability for extensive hours of work. It is common knowledge that architecture is a discipline where the culture of long hours is deeply entrenched and even glorified (Fowler and Wilson, 2004; Burns, 2016). In the Estonian context, this is exacerbated by cultural norms whereby women have traditionally seen work (either domestic or professional) not only as an obligation and self-justification but also, paradoxically, as a source of vital power in its own (Kirss, 2002). Research of Estonian women’s life stories has shown that work and productive activities in their various manifestations form a central node in women’s identity but it is crucial that this is not understood as building a career for oneself but rather as a servicing activity in the name of common good, the community, or the family (Annuk 1997). Irina Raud fully conforms to such work ethic of full devotion, citing her father Paul Luhtein, a renowned graphic artist working extremely long hours as an inspiration and a role model, and claiming proudly that never in her life did she take time off from work for longer than a week. She also compared her devotion to work positively to some other female colleagues who juggled their family responsibilities with work less successfully: “It is not quite that I did not like children but that I really loved my work.” In this context, it must be noted that the gender roles in her family were not quite traditional: in an interview to a women’s magazine Eesti Naine (Estonian Woman), Raud has explained that her massive workload was possible due to major support from her husband who, in addition to being a good discussion partner as a construction engineer, took also main responsibility of grocery shopping, cooking and other domestic chores, an arrangement quite uncommon during the Soviet times (Kaik 1991). In the same portrait story, she admitted that her only child was a very easy one to raise, and explained that taking her child as an equal partner in a family has always been part of her parenting principles. However, she also said that under different circumstances she would have liked to have at least three children and work much less - a confession that somewhat contradicts all her other interviews and portrait stories and could perhaps be partially attributed to the bias of the magazine that tended to valorize traditional gender roles in tune with the prevailing social and cultural spirits of the transition era.

While conforming to a very masculinist take of an architect, on the one hand Irina Raud claims her own exceptionality but on the other she also implicitly acknowledges the difficulties she has had to overcome. In the 2018 interview she admitted that when teaching, she tends to warn young girls that the profession might not be suitable for a woman, and it should be pursued only if the calling is strong enough to counterbalance the hardships. Indeed, a portrait story about her in the main national weekly was titled Lady of Steel (this was also an easy wordplay: her surname Raud means ‘iron’ in English) (Kangur 1996) where her success was attributed to a combination of excellent background, intelligence, social skills and self-confidence, concluding that she would make a good president for the country. This was just one instance among many where this archetype was used as a lens for her public representation, testifying to media’s disposition to portray women according to pre-existing stereotypes (Pilvre, 2009)6.

Margit Mutso, president of the Union of Estonian Architects (2004-2005)

Margit Mutso (figure 3) assumed her position as the president of the Union of Estonian Architects during the next great social and political transformation - in 2004, Estonia joined the European Union, which entailed changes in legislation, brought along new regulations, and opened up possibilities for European structural funding, all of that greatly affecting architecture, construction industry and infrastructure. Having graduated from the Estonian Academy of Arts (then National Institute of the Arts) in 1989, Margit Mutso had commenced her professional path at a time when borders were opening up with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and she was among the first young architects to obtain some professional experience abroad, practicing in Finland for three years. Soon after returning to Estonia, in 1996, she established a joint practice with her husband Madis Eek, designing mostly residential architecture but also some commercial and public buildings and successfully participating in urban planning competitions. Very much from the start, in addition to design practice, she found energy to participate in public discussions concerning the profession, being one of the most prolific commentators of spatial matters in mainstream media, leading an architecture section in a popular TV broadcast, and in 2010 - 2013 serving as the architecture editor in the cultural weekly Sirp. In 2002 - 2010, she also wrote and produced annual promotional films of award-winning contemporary Estonian architecture, and has authored documentaries of renowned architects Fredi Tomps (2017) and Leonhard Lapin (2020) and the hundred years of history of the Union of Estonian Architects itself (2021). Thus, publicity of spatial matters of all kinds, and architecture’s potential as a vehicle for public discussion have always been among the central concerns of Margit Mutso’s professional activities.

Defining herself primarily as a team player, in the 2018 interview Mutso admitted that becoming a president of the architects’ union was less of a career goal than an act of social responsibility, driven by a strong push from her colleagues (Mutso, 2018). This again conforms to the vision of woman’s work as something that should primarily serve the community or the greater good instead of pursuing personal aims (Annuk 1997). Rather than having a very clear personal vision of the future of the union she said she mainly tried to realize ideas and concerns shared by most of the active members, trying primarily to steer the discipline safely through the period of changes (Mutso, 2018). It was a turbulent period indeed: in addition to adapting to the regulations coming with the European Union, the two years of her presidentship were a time when some of the most controversial architecture and design endeavours in Estonia took place, causing a lot of heated public discussion, including the demolishing of Soviet-time party headquarters building in central Tallinn, the international competition of Estonian National Museum to a site of a former Soviet military airfield, and the decision to start participating at the Venice Biennial on a recurring basis.

Reflecting upon her experience in that position, Mutso said that she really acknowledged her exceptionality in such a role, especially when representing Estonia abroad where she did not encounter a single woman in similar positions of power. When negotiating the preparations for joining the Venice biennial, communicating with governmental and professional offices in Italy had involved situations where the officials did not even believe she was actually the president of the union, being a woman under 40 (Oma tuba, 2019). In her everyday work in Estonia she claimed that she had not encountered gender-based discrimination, and occasional catcalling by the builders on a construction site was, to her mind, not an issue much worth mentioning. At the same time, she said that in the Estonian context, primarily on the public arena, the fact of having been a leader of the whole profession has granted her a certain respectability that lingers on years later, adding to the weight of her opinions in the media or facilitating professional and bureaucratic negotiations (Mutso, 2018).

Nevertheless, Margit Mutso definitely does not represent the tough and masculinist career architect but, paradoxically, has voiced opinions that sound traditional or even rather conservative. In the 2018 interview, she claimed that as a rule, best architecture is authored by men, and women tend to be naturally less ambitious, having no desire for a lot of responsibility at work when they inevitably are the main caregivers at home (Oma tuba, 2019). She also seems to represent the point of view that women design essentially differently than men, paying more attention to the tactile aspects of space, everyday comfort and nuances like terraces, greenery and outdoor spaces in general, playgrounds for the children, etc. Pointing up the high quality of most notable Estonian women architects Valve Pormeister and Siiri Vallner, she is certain that what distinguishes their work, in spite of generational differences, is contextuality, dialogue with the surrounding environment and keen attention to tactile details, qualities that she attributes to their feminine relationship with the environment (Mutso, 2018). This could also read as implicit criticism that such aspects of design are often overlooked in highly accoladed architectural solutions authored by male architects - the mainstream standards of excellence tend to value visual attraction and rational programming, paying less attention to everyday user experience and the subtler aspects of space. In an equally critical note, she sees the difference of men and women architects also in the question of solidarity, claiming that if the Architects’ Union occasionally advises not to participate in certain competitions due to the client’s violation of rules of best practice, women architects would stand in solidarity but there would always be some men who, for the sake of easy money, participate nevertheless.

In her own designs, Mutso claims to strive for a certain poetic touch, a metaphysical quality even, and tries to avoid too rigid and rational floor plans, describing this also as a feminine quality. She values historical character of a site and tries to incorporate dialogue with the previous layers of space. Describing the organization of workload in their joint practice with Madis Eek, Mutso also seems to adhere to certain stereotypes, saying that while one or the other would bear the main responsibility for a project, she would nevertheless check all the landscaping and minor details of the projects of her husband while he would have a look on the structural solutions of the projects of hers. At the same time, their roles in domestic life are more or less egalitarian (Mutso, 2018).

Respectively, Margit Mutso has never shied away from incorporating femininity in her public persona. She has willingly presented herself in the company of children, and dogs, horses and birds that she breeds, a most vivid example perhaps being a portrait story in a women’s magazine (Laanem, 2006). In the feature, she has not felt the need to control the public representation of herself to convey the typical image of an architect as a serious, exacting and highly intellectual professional. She does talk about professional matters indeed but, in addition to that, also freely shares recollections of wild times as a student, a short career as a cabaret dancer, and an anecdotal story of being elected Miss Emergency Ward by male patients while being confined to a wheelchair after a car accident (Laanem, 2006). Quite atypical for an architect, the story stresses the joyful and hedonistic side of life among children, friends and animals. At the same time, she does acknowledge the enormous workload that came with combining running a private practice with the role of the president of the architects’ union all the while raising two small children. But, unlike the women architects of the previous generation, the devotion to work is not presented as a glorified act of sacrifice: Mutso is among the very few who have admitted burnout due to the stressful work situation. She has not felt the need to build a tough image of herself as a leader, and the story does not present architecture as a special calling that would justify self-sacrifice in other realms of life. Talking about matters like burnout without self-pity and not presenting herself as a failure, Margit Mutso has certainly helped to raise consciousness about the conflicting demands upon a high-achieving woman and the toughness of work culture in architecture.

Katrin Koov, president of the Union of Estonian Architects (2016-2020)

Katrin Koov (figure 4), the recent president of the Union of Estonian Architects, has likewise said that applying for the position was mostly due to strong persuasion of the colleagues who have always appreciated her acute social nerve and good communication skills. At the start of her career in 2002, Koov was among the four founding members of Estonian first all-female architecture office Kavakava with Siiri Vallner, Veronika Valk and Kaire Nõmm. The birth of Kavakava may be seen as the first instance of conscious gendered critique of architecture culture among the practitioners. All four members of Kavakava had graduated from the Estonian Academy of Arts at the end of the 1990s and acquired their initial design experience in different Estonian small-scale practices while at the same time actively participating in open competitions on their own, contributing to a notable wave of young architects whose careers were launched with bold public buildings resulting from competition wins. In the case of Koov, the first one was the Pärnu concert hall designed with Kaire Nõmm and Hanno Grossschmidt and completed in 2002. With the team of Kavakava, successful competition designs of Pärnu central gymnasium (2003, built 2005), Narva college of University of Tartu (2005, completed 2012) and several others followed. At the same time, she started teaching at the Academy of Arts, initiating a new curriculum of urban landscape architecture, and wrote design criticism in professional and mainstream media. The logical follow-up to the latter activities was her becoming the editor-in-chief of the local architectural review Maja in 2014, a position she held for three years, steering the magazine towards greater dialogue with neighbouring professional fields and aiming at a less elitist rhetoric in the discourse. She is also one of the long-time teachers at Architecture school, a self-initiated endeavour to compensate for the lack of spatial education in standard primary and high school curricula that grew from hobby education classes to an elective programme available for high schools.

According to my interview with Katrin Koov, the goal while establishing Kavakava was to counter the masculinist design values, elitism and work culture that they encountered in practice, and to search for working modes that would be based on co-operation and enable more flexibility (Koov, 2018). Concerning gender-based discrimination, she admitted that it was something subtle yet widespread and bothered her more at the beginning of her career, especially when dealing with dominant personalities in the construction industry or among clients. Thus the Kavakava architects also felt it would be easier to counteract these tendencies as a team (Läkk 2003). Some of the founding members had young children (Katrin is a mother of three) and part of the motivation was to find arrangements for better work-life balance, however Koov admits that this ideal soon proved unsustainable: with demanding commissions of public buildings to handle and numerous open competitions to take part in, it was clear that work concerns overrun much else and raising children alongside was as tough as ever (Oma tuba, 2019). In a way, the success of the young office was also something that counteracted to their ideals, so the experiment of Kavakava eventually reformulated into a more traditional design office and some members left. Nevertheless, Koov stresses the importance of co-operation throughout her professional activities. She values highly dialogical processes of design and supports resistance to architecture’s star system. However, she does not see it as a specifically feminine or feminist trait but rather as a general movement towards greater acknowledgement of dialogical and co-operative component in the creative processes of architecture (Koov, 2018).

The design principles of Kavakava have similarly emanated from the desire to counteract an elitist and hermetic notion of architecture by stressing the everyday qualities and bettering the spatial experience of an ordinary user instead of producing big statement design (Mutso 2012). Ever since her student times, Katrin took great interest in issues of urban landscape and tended to focus on experience of intermediary spaces, undefined environments and everyday users. In the 2018 interview she said that she very clearly acknowledges her position as a facilitator, interpreter and negotiator of issues and relationships of space: this is the starting point of the design process as a journey where imposing one’s own ego or unique vision is not the main goal (Koov 2018). A similar credo has served as a backdrop for her presidency as well, where she sees herself as a team player and facilitator within the union as well as when reaching outwards to negotiate wider policies. She clearly defined the role as an opportunity to expand her architectural principles to a larger scale, based on the ideas of democratic and inclusive space and architect’s social responsibility (Veski 2016). Fostering cooperation both within the wider field of architecture and with neighbouring disciplines should make design competence more widely attainable and applicable in different social fields (Koov, 2016a). The other recurring subject of her tenure as a president has been spatial education, an issue she has raised over a number of opinion articles and interviews (Karro-Kalberg, 2016; Koov, 2016b). She has stressed that laying the basis for future improvements starts with attention to children - introducing general spatial education to primary and high schools, and overall improvement of educational spaces.

In spite of being active in the media - both during and after her presidency Koov has written a number of opinion articles in newspapers, not to mention her activities as the editor of the Estonian architectural review Maja - Koov has refrained from any portrait stories of herself that would hint at anything about her personal life and has kept her public persona deliberately professional. Her public appearance is always composed, level-headed, rational and open-minded. Soft values, inclusive spaces and equal opportunities for marginal user groups in architecture and urban space have been at the core of her public comments (Koov 2016a; Koov 2016b; Veski 2016), however she has refrained from framing these principles as anything explicitly feminist. On the one hand this reflects increasing acceptance of feminist values in mainstream discourse; on the other, this testifies that there are still strong prejudices of explicit feminism as something too aggressive, challenging or disruptive. Similarly, reflecting upon her own experiences in studying and practicing architecture, Katrin has admitted to inequalities and unfair treatment in academia or construction business, and described building up confidence as a woman architect as challenging; yet she has been quite cautious in addressing it as a systemic problem and admitting the need for feminist action only tentatively.

Conclusion

Based on these four cases we can see that the transition from Soviet to post-Soviet context in Estonia has brought along significant changes in the ways of establishing oneself as a high-achieving woman architect in power position and what kind of self-identification and construction of public persona it requires. At the same time, certain cultural norms and attitudes rooted in the Soviet period continue to affect the internalized expectations and self-perception of woman architects until today. As mentioned above, the Soviet period had a mixed relationship to feminist agenda which did provide certain emancipation but remained even more a facet of ideological propaganda. For the Estonians under occupation, the need to resist and mentally dissociate themselves from anything related to Soviet ideology included a deep suspicion of feminism even if they benefitted from it in their everyday experience. At the same time, the post-Soviet transition meant a desire to turn back to pre-occupation, pre-war values and cultural norms, including the conservative gender roles of the 1930s. This combination still affects practitioners today and has made open and conscious embracing of feminism difficult even for those who actually share its principles. The four case studies show that both Soviet and post-Soviet generations of women architects have a highly ambivalent relationship to feminism and to their own role expectations in the field. While often finding themselves as the only women in the higher ranks of architecture profession, they mostly still do not recognize it as a systemic problem - the achievements or failures of a woman architect are only addressed on an individual basis. Accordingly, extreme workload and difficulties of work-life balance are being accepted as inevitable in the profession, although the transition to post-Soviet period has brought along acknowledgement of the problem. The contemporary high-achieving women architects are beginning to see the opportunities for constructing less masculinist public personas and to promote softer values both in design as well as in the work culture. All this can create paradoxical situations where there is discrepancy in women’s choices, actions and rhetoric, and regrettably sustains understanding that women’s achievements are exceptional and can only result from extraordinary talent and hard work, something Justine Clark has identified as one of the core myths of architecture (Clark, 2016, p. 15). The reluctance of openly call oneself a feminist still prevails but it also has another side. Karen Burns has pointed out that refusal to frame oneself as a woman architect might not be a surrender to the masculinist view of discipline but also a conscious choice to define oneself on one’s own terms (Burns, 2012). In either case, these four women have served as important role models, diversifying the public face of architecture, while also working to introduce important values like openness, collaboration and inclusivity to the local discourse.