1. Introduction

Originating from a critique of women's*1 living and working conditions in the 19th century, feminist critique of planning today can already look back on a long history and has experienced increasing popularity since the 1970s.

However, even today, the focus of feminist planning theory and practice is much more often on housing and the living environment than on a comprehensive analysis of urban spaces. (Doderer, 2002, p.3)2

Women’s* housing and living conditions, as well as the role of women* as users of urban spaces and in planning, architecture, and activism, are important components of feminist critique. Nevertheless, it is also important to analyse and criticise the general modes of production of the city from a feminist perspective. In her text ‘What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work’ (1980), Dolores Haydn writes about this emphatically, incorporating the entire context of settlement:

When all homemakers recognize that they are struggling against both gender stereotypes and wage discrimination, when they see that social, economic, and environmental changes are necessary to overcome these conditions, they will no longer tolerate housing and cities, designed around the principles of another era, that proclaim that ‘a woman's place is in the home’. (Hayden, 1981, p.187)

Following the much studied and discussed aspect of the gendered separation of productive and reproductive labour based on which urban and built structures are designed (Doderer, 2002; Becker, 2004), it is becoming clear that the distinction between public and private, productive and reproductive spheres needs to be overcome as an inherent characteristic of the hegemonic understanding of the city. This separation is crucial as a category of analysis to uncover existing inequalities and requires critical consideration in order to think beyond those categories themselves (Wischermann, 2003).

In order to understand what feminist utopias respond to, the spatial creation of opposing spheres to separate private and public, domesticity and work, and the construction of associated gender narratives are first illuminated. (Reuschling, 2013, p.29)3

Felicita Reuschling, following Dolores Hayden's analyses and proposals for the non-sexist city, proposes including the idea of the commons in the considerations of the non-sexist city. Reuschling describes how the idea of the commons shares many parallels with Hayden's ideas and offers an approach to reflect on a different city in a way that is both utopian and practical.

1.1. Questions on feminist spatial production in Berlin

To understand and combat sexist structures and their consequences on the one hand, and to discover or develop alternative designs of a feminist city on the other, posing questions about the spatialisation of inequalities and correlations to urban spaces and practices is crucial. A non-sexist city can only be conceived based on the assumption that ‘social gender relations [...] are inscribed in the spatial structures’ (Becker, 2008, p. 798), meaning that our built environment is neither value-free nor neutral. Although feminist critique of existing systems always starts with an analysis of power relations and inequalities, it also addresses the possibility of liberation from these relations and thus promotes self-empowerment and a better life for all. This ambivalence is particularly evident in the study of spatial phenomena, as structural inequalities materialise in these phenomena and can thus be made visible. The situation is similar with regard to self-empowerment, emancipation, and liberation from oppression: Traces are left behind in space, making it possible to understand social actions and relationships.

Based on this reading of a feminist history of architecture and planning critique, three central questions can be derived. In turn, these questions can contribute to the exploration of the potential behind a consideration of feminist spatial production by means of mapping:

What structural inequalities can be identified in urban space in the example of Berlin?

What could a non-sexist city look like? How can the spatial separation between public and private be overcome?

How can a feminist perspective (of Berlin) be developed that includes the conditions of the production of feminist spaces and thus makes them conceivable and imaginable as different conditions in the future?

The three resulting questions indicate that the inequalities revealed in space and in their agglomerated form can be interpreted and analysed as hegemonic spatial systems. Furthermore, the questions point to the fact that, as a reaction to and defence against these inequalities, spatial systems can emerge that are characterised by an opposing feminist spatial production.

The assumptions and references from feminist research history described before determine the setting for the mapping research on which this article is based. It refers to the text ‘A Feminist Perspective for Berlin Today! What Could a Non-Sexist City Look Like?’ (2017) by Felicita Reuschling and thus draws on Berlin as a space of analysis for examining the possibility of a non-sexist city.

The first part of this article describes the methodological approach and the different working steps, while the second part summarises the results of the empirical study. Subsequently, the third part discusses and synthesises the results as a re-reading of maps as the principle means of analysis. In the last part, we reflect on a future, feminist city, which can be understood as a possibility for further thinking, research, and implementation, as well as on the mapping methods used and their appropriateness for researching the non-sexist city.

2. Methodology: Feminist artistic positions as a starting point for drawing-based explorations of space

The methodological approach used to investigate the above-mentioned research questions was a practice-related teaching and research format at the Chair for Urban Design and Urbanisation at TU Berlin. The starting point was the exhibition ‘A Feminist Perspective for Berlin Today! What Could a Non-Sexist City Look Like?’ initiated by Felicita Reuschling and developed in cooperation between the Chair and the feminist art space alpha nova & galerie futura (Katharina Koch and Sylvia Sadzinski) in Berlin-Kreuzberg. The seven exhibition contributions position themselves against a sexist Berlin by addressing the emancipatory potential that the city already incorporates and attempting to expose it through collective, institutional, self-empowering, or subversive performance4.

From the feminist artistic positions selected for the exhibition, we derived several different themes, which we explored together with 31 students from different cultural contexts in an online research and mapping seminar (fem*MAP Berlin). Their personal experiences as women* in urban space were mapped as an initial approach to the topic. The students developed cartographic explorations based on online research, interviews, participant observations, digital map services, and descriptive-speculative spatial visualisations. These methods perceive and analyse both feminist and hegemonic spatial systems differently in the context of Berlin. Some of the research groups focused on practices of evasion by women* in everyday urban situations and thus on the implicitly repressive spatial structure of the city, which resulted in the description of hegemonic spatial systems. The other groups made the emancipatory practices of empowerment visible, which open the view to non-hegemonial, feminist spatial systems.

At the end of the seminar, the research results were documented in a collection of thematic atlases consisting of maps and diagrams. From theses analyses, the students created collage-like texts or images (‘puzzle pieces’) as speculations of transformative potential for a future non-sexist Berlin.

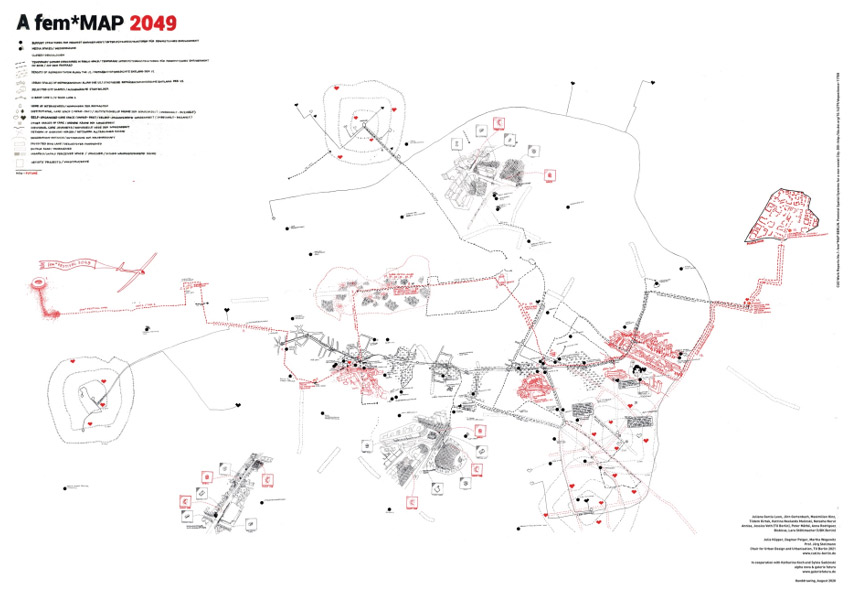

Building on these speculative extracts, including maps, theses, and puzzle pieces from the students’ research, a synthesis map of Berlin was created during a five-day mapping camp with a partially new group of ten students.

Three successive steps were taken within the framework of the collective mapping experiment with the aim of developing a future feminist spatial structure of Berlin from the elements of the thematic atlases and their interpretation. First, the central arguments from each atlas were transferred onto an integral map of Berlin, creating a basis for a complementary counter-mapping (Harley, 1989) in a critical inventory of the hegemonic spatial system

The readings from the critical and counter-mapping developed for each of the research topics from the thematic atlases were superimposed in the second step. Their drawings and content were reviewed and refined according to their interactions until a coherent picture (Marguin et al., 2021) of the implicitly hegemonic and explicitly feminist spatial systems emerged from the many transparent layers of paper.

In the third step, a second drawing layer was developed. This second layer supplemented the interpretive assessment of the unequal availability of space for women* and the appropriations by women* that overcome inequality with future spatial systems. The various future-oriented puzzle pieces were further developed in the course of the mapping process and thus integrated into a comprehensible description of the future traced in drawings and narratives.

As part of the exhibition ‘A Feminist Perspective for Berlin Today! What Could a Non-Sexist City Look Like?’, fem*MAP 2049 was exhibited as one of the pieces of art alongside the six artistic positions, together with an expansive cartographic installation of select elements from the map translated into the gallery space.

Source: Ceren Saner.

Figure 3. Cartographic installation

Following the exhibition, the results of the research were consolidated in a revision of the fem*MAP 2049. The thematic atlases and the two-page fem*MAP are available as an open access publication on the repository of the TU Berlin University Press and form the basis of this paper.

2. Empiricism: Feminist spatial systems in Berlin today

This section catalogues the results of our teaching-based research format, including the various steps such as the student researches (thematic atlases), the collective mapping experiment, and the synthesised spatial installation. To describe the results, we move through the study spaces of Berlin from the inside out: that is to say, from the ‘private’ sphere of the house and the interstices of the ground-floor zones to the ‘public’ sphere of streets and open spaces. We begin with an analysis of Gender-Specific Housing Conditions (Atlas 5), which focusses on the most private interior spaces of the city and examines their nature as a safe home. In the description of the Places of Neighbourly Caretaking (Atlas 3), the focus shifts to the transitional spaces between home and the street, questioning their capacities as spaces for reproductive labour. Finally, with examinations of Queer-Feminist Spaces of Empowerment (Atlas 2), along with spaces of Remembrance, Representation, and Politics (Atlas 1), we reach the public space of the city, which reveals the largest pre-existing share of feminist spatial production. A fourth description briefly summarises the results of combining the essential information from the individual thematic atlases into a collective map.

2.1. Gender-Specific Housing Conditions

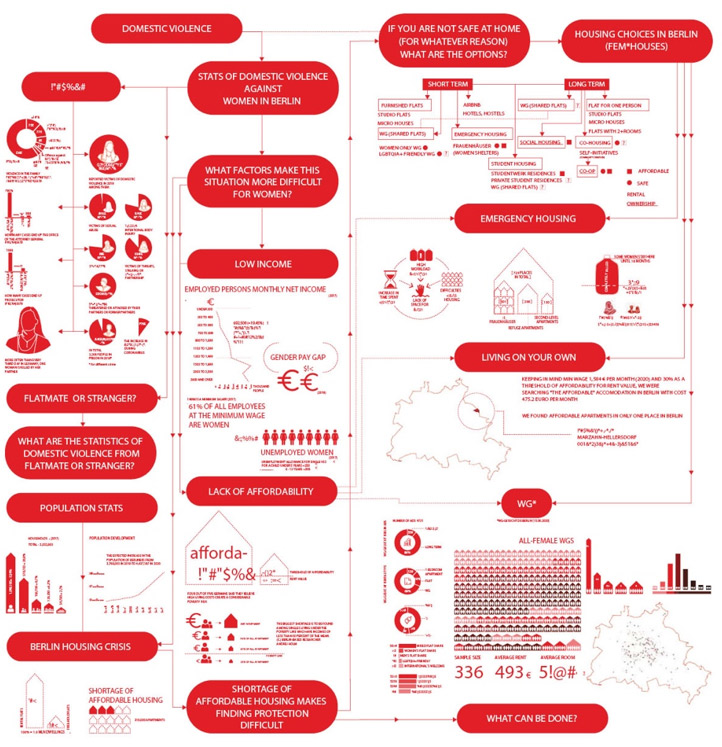

The research on Gender-specific Housing Conditions (Atlas 5, Ekaterina Kropacheva, Feyza Sayman, Nikita Schweizer) analyses the accessibility of the Berlin housing market for women*. In doing so, it combines the question of housing availability and affordability with questions of safe and violence-free homes. The somewhat pointed hypothesis used by students to begin their research describes Berlin as a largely unsafe space for women*, characterised by the permanent presence of sexualised violence in all public spaces. The potential vulnerability of women* resulting from this in the public sphere is translated to private living situations.

By comparing the availability of housing, based on criteria such as rent, location, size, and type, with the factor of security in the sense of a violence-free home, the analysis illustrates how the housing crisis forces women* to live in places where security and integrity are only conditionally guaranteed. Using detailed case studies of explicit housing situations based on interviews with women* and precise floor plan analyses, they show which residential areas are actually defined as safe and thus a separate space for women*. These areas are correlated with the rent paid, thus calculating rent per sqm of safe living space. Infographics are used to merge the extensive research on housing requests and offers with the analysis of Berlin-specific statistics on domestic violence, which mostly originates from partners or other family members, but also from roommates or even guests. A third strand of data is devoted to aspects of the housing crisis in Berlin and related issues of housing shortages.

Four criteria play a key role in bringing together these three strands of data: affordability in terms of income-which for women* is on average 21 percent lower than for men (German Federal Statistical Office, 2019)-opportunities for self-determination in terms of apartment floor plans, rent permanence, and social fabric within the resident community. Only when all four criteria are met can one speak of a safe home that offers permanent affordable living space for a self-determined, violence-free life.

The parameters limiting this intersection of availability and security reveal the economic dimension in women’s* search for housing superimposed by the political and social dimension. The lower salaries, (not only) physical vulnerability, and questioning of self-determination of women* are three central structural disadvantages that apply to different social groups and represent characteristics of inequality. But in the case of women*, who make up half of the population, the disadvantages regarding economy, body, and self-determination overlap. They thus weigh more heavily and also have a direct impact on housing and on the most vulnerable spaces of everyday life.

Accordingly, the research primarily highlights the consequences for women*, who have to organise themselves in Berlin's hegemonic housing-space system, facing housing shortages and structural vulnerability. The analysis shows that the solidarity principle of the shared flat, as an originally emancipatory means of communalised housing provision, is being undermined due to the shortage of living space. Moreover, the concept of shared living space is being transformed into relationships of dependency between (sub)landlord and (sub)tenant at the scale level of the individual rooms within the flat. The market economy principle replaces the solidarity principle within the ‘shared’ flat (Köpper et al., 2021, p.212). The flat is economically valorised and thereby devalued as a type of temporary ‘accommodation’ in the logic of dormitories with reduced or no common spaces. This shortage of common spaces leads to a lack of social control among those living together (Kelling et al., 2020). In this process, the privacy of the apartment as a protected space gradually dissolves, which has far-reaching consequences as shown in the interviews. What was originally intended to serve as a personal space and to guarantee security and familiarity has become a bartering object for centrality, connectivity, and proximity to work or education.

The vision of an emancipatory future puzzle piece rests on the solidarity principle traditionally underlying the phenomenon of shared housing. The future described here is driven by the perspective of living together in solidarity in self-determined, cooperative forms of living. According to the students, as long as there is no guarantee of affordable housing for all, the emancipatory potential lies in the solidary (residential) community.

2.2. Places of Neighbourly Caretaking

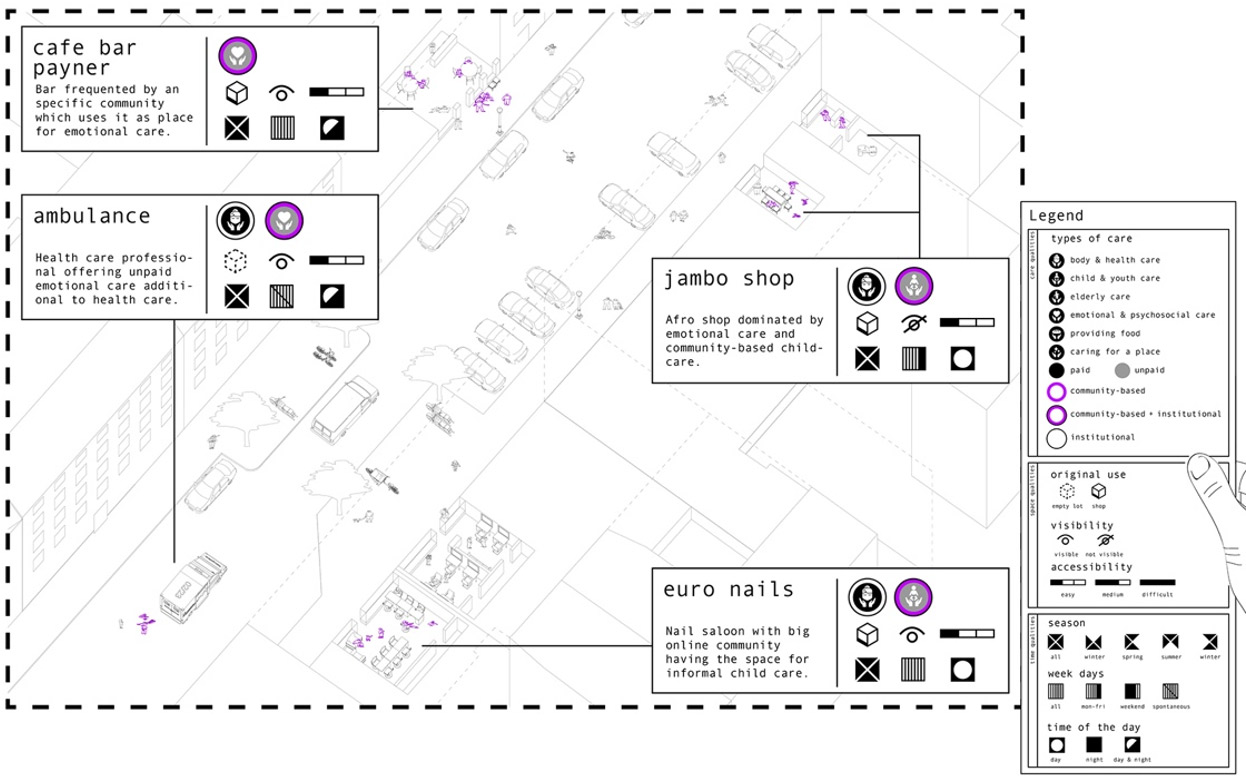

Based on the analysis of community caretaking at a local scale in the Berlin district of Wedding, the research on Places of Neighbourly Caretaking (Atlas 3, André Sacharow, Juliana García Léon, Julia Gersten) addresses the issue of new spaces and forms of caretaking. The analysis clarifies to what extent, and at what level, spaces of self-organised caretaking complement the incomplete system of state and private-sector care, and how much the different systems are intertwined with each other. It reveals that community caretaking is hardly visible in the discourse on the caretaking to date, but that it should be part of a future, non-sexist, empowering, feminist spatial system of reproductive labour, which will require appropriate spaces and suitable infrastructures.

Given the fact that women* worldwide perform three times as much unpaid care work as men (UN Women, 2019)5, and referring to Silvia Federici's call (Federici, 2012) to use the crisis of care systems to bring forth a new society of community-based domestic work, the research outlines what spaces and systems of caretaking are needed in a non-sexist city based on solidarity and equality.

Therefore, this atlas examines which forms of caretaking are performed within society and how visible or invisible they are. Within households, caretaking is unpaid and invisible, hidden inside the private sphere. The public sector provides educational facilities, but also physical infrastructure in public space. The non-profit sector plays a significant role in Berlin, providing not only the vast majority of day care centres for children, but also homes for the elderly and psychosocial facilities. The for-profit, private sector focuses on the care industry and hospitals, with a strong upward trend6. Personal care service providers such as hairdressers, massage therapists, and nail salons also belong to this sector, whereby these are often marginalised spaces of intimacy and encounter, where a form of emotional care takes place alongside physical care.

Mapping was used to investigate how forms of communal, self-organised caretaking are performed on a neighbourhood scale. For this purpose, three different methods were combined: participant observation in the neighbourhood, interviews with residents, and a collective map on which passers-by marked the spaces of caretaking they use every day. The axonometric map created from this information gathers spaces of caregiving within the studied streets and thus draws a network of these spaces, which cannot be found in statistical data systems although they are ubiquitous and make a great contribution to easing women’s* everyday lives.

Focussing on the self-organised level of caretaking reveals the extent to which this complements the incomplete system of governmental, non-profit, and private sector care services. It also highlights the different spatial settings beyond public, non-profit, and for-profit care spaces, in which the different systems are intertwined. Commercial spaces such as a nail salon in Wedding, for example, are places where emotional care and community-organised childcare take place simultaneously alongside business activities. Likewise, spaces such as backyards are appropriated for informal, neighbourly caretaking, as neighbours use their yards for interactions and shared childcare. Communal caretaking is supplemented on the streets, for example, by non-governmental organisations offering after-school activities for girls and by the Muslim community offering tutoring and other activities for children.

As a speculative outlook on the possibility of other structures of caretaking, the research group formulated criteria for enabling and networking neighbourly care structures. These include the networking of care spaces with a flexible mobility network allowing for individual routes and access for those providing or receiving care, the promotion of solidarity-based residential communities and collective forms of housing for communal caregiving at the residential level, and the establishment of spaces for affordable communal caretaking at the neighbourhood level.

2.3. Queer-Feminist Spaces of Empowerment

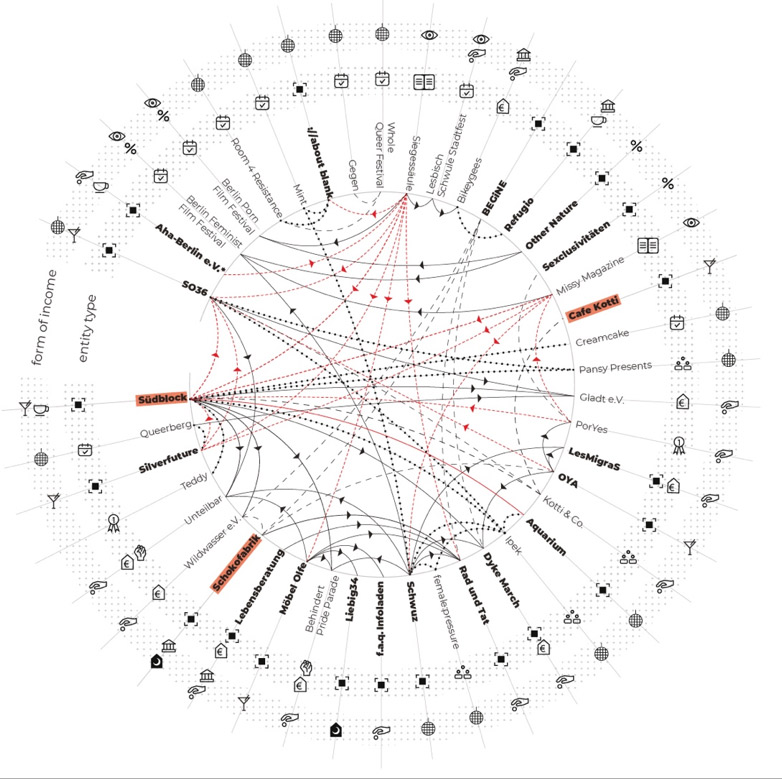

The research on Queer-Feminist Spaces of Empowerment (Atlas 2, Rowaa Ibrahim, Sebastian Georgescu, Katrina Neelands Malinski, Solveigh Paulus) is based on the assumption that a network of queer-feminist spaces of empowerment exists, distributed across Berlin. Furthermore, it assumes that these places are closely interwoven socially and financially, despite spatial fragmentation, and that this is perceptible in concrete space. The focus of interest was the functioning of such a queer-feminist network and its spatial manifestation as spaces of empowerment. Martina Löw’s relational theory of space as the interface for actions, participants, spaces, and sets of rules (Löw, 2001; Kelling et al., 2020) makes it possible to comprehend the complexity of these spaces.

Initial spaces of empowerment were selected via an Instagram survey. Based on the places mentioned in the survey, research was conducted on other queer-feminist places, actors* and their connections, networks, and relationships. The data collected, consisting of literature, online research, and fieldwork, revealed that beyond places and other (known) actors, this network also contains diverse political groups, festivals, magazines, artists, and performers.

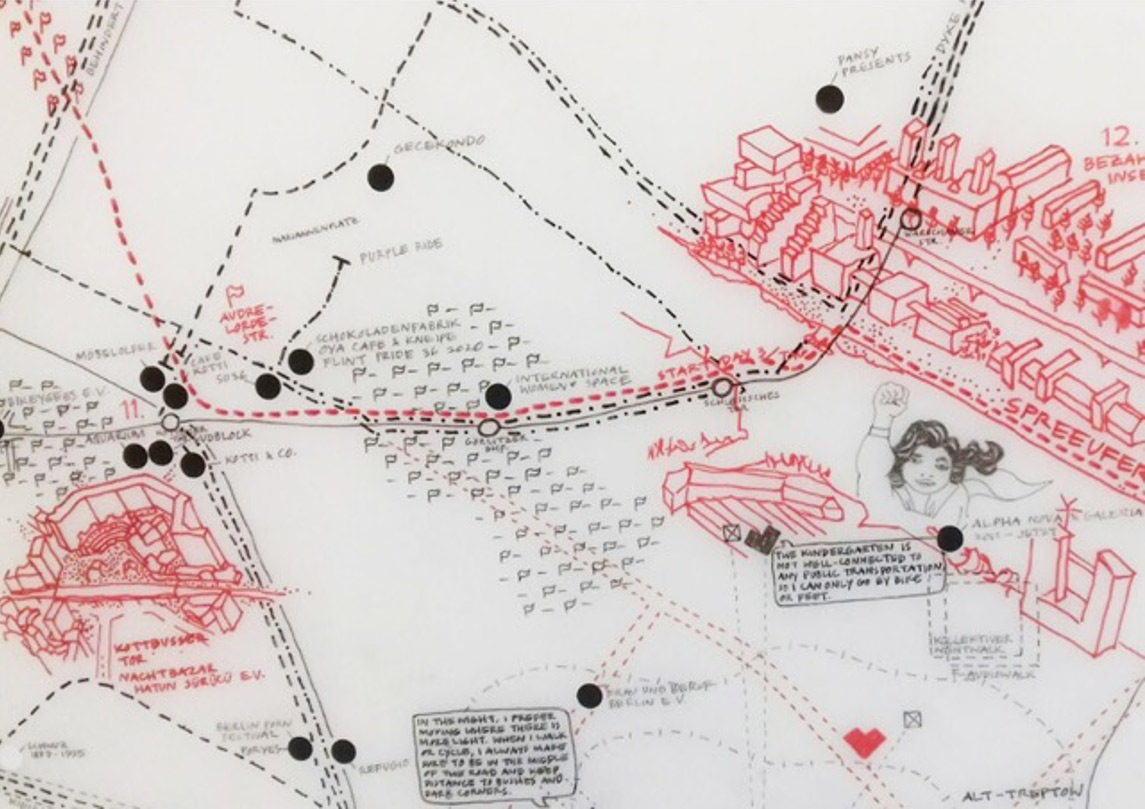

The mapping of the network shows the multi-layered relationships between queer-feminist places, events, and institutions in Berlin. This involved identifying recurring events, venues, and themes, examining the economy (or economies) of each element, uncovering and analysing relationships, and looking at past or current threats to the continued existence of these spaces. In both the socially and structurally diverse environment of Kottbusser Tor in Berlin-Kreuzberg, there is an accumulation of queer-feminist sites. The overlapping of different structural layers is typical for this environment. The direct neighbourhood between factories once occupied by squatters, apartment buildings, and large housing estates on the former outskirts of West Berlin has for many years provided the now scarce space for political movements and subcultures.

The students chose three examples to examine more closely, particularly with regard to the spatialisation of the network: Südblock, Café Kotti, and Schokofabrik. The three places were chosen because of their different functions and modes of operation, spatial structures, and forms of accessibility. Südblock is a very public gastronomic venue located directly on the square next to Kottbusser Tor subway stations and serves many functions within the network (providing spaces, consulting services, support in financing projects also for queer people). Café Kotti is more of a retreat with neighbourhood functions, at a somewhat hidden location at the New Kreuzberg Centre. Schokofabrik is an important feminist institution in Berlin since the 1980s. It carries out many functions within the network: for example, it houses some of the actors* who are also active in the network and offers concrete services for women*. Only girls* and women* are permitted to enter and use this building complex, which was formerly occupied by squatters and is now owned by a cooperative.

Studying the empowerment network and individual locations within the network shows that, despite the spatial fragmentation, there are strong connections and common sets of rules that are expressed linguistically, influence social relationships, but can also be read spatially. It reveals multi-layered, solidary relationships between the spaces of empowerment, such as a system of solidary (co-)financing, support in struggles to preserve spaces, the provision of spaces and resources, and mutual support in organising and implementing events and projects.

Rowaa Ibrahim, Sebastian Georgescu, Katrina Neelands Malinski, Solveigh Paulus

Figure 6 Network of Spaces of Empowerment

Many elements of the network share similar sets of rules that influence the actions and behaviour of actors and users, as well as spatial arrangements (Löw, 2001). Sets of rules are understood here as verbal and non-verbal systems (Kelling et al., 2020, p.152) that provide for spaces of empowerment and at the same time can be found as traces of the network in space. The network and its sets of rules become readable in spaces thanks to their concrete spatial design, direct verbal cues, or indirect spatial cues. Concrete spatial manifestations of these sets of rules include, for example, posters or stickers indicating certain rules of behaviour. One example of a concrete spatial design that represents these sets of rules is gender-neutral restrooms.

2.4. Remembrance, Representation, and Politics

The research on Remembrance, Representation, and Politics (Atlas 1, Hsiao-Lan Chuang, Natasha Nurul Annisa, Paul Bostanjoglo) explores critical feminist representation along subway line 1 in Berlin. This resulted in a fragmented map of different locations along the subway line, which can be perceived as a snapshot of practices and materialisations of critical feminist representation. In the context of the previously described analyses on spaces of empowerment, it is particularly interesting to pick out the informal aspects of representation in order to highlight their relationship to the network under investigation.

The mapping of the numerous objects found reveals a production of space through practices of critical feminist representation, also disclosing a connection between the practices and objects in the empowerment network. For example, posters or stickers refer to places, events, or political groups that are part of the network. This connection between actors* in the network and practices or objects of representation can also be made in the opposite direction-not only from the object to the network, but also from the network to the object-because materials of representation are largely provided and distributed by groups, places, and people from the empowerment network.

An ever-expanding network of spaces of empowerment is envisioned as the speculative future of a non-sexist city. Feminist spaces are no longer fragmented across but rather expand throughout the city, opening up ever new spaces that enable women* to operate free from oppression. Signs and elements of critical feminist representation now show up everywhere along subway line 1 in a variety of forms.

2.5. Nightscapes and Moving Through Berlin

The research on Nightscapes (Atlas 4, Yu-Pin Chiu, Tamar Gürciyan, Maximilian Hinz, Tildem Kirtak, Kamal Maharjan, Santiago Sánchez) and Moving through Berlin (Atlas 6, Elif Civici, Jörn Gertenbach, Sena Gür, Jessica Voth) deals with the question of how walkable the city of Berlin is from a feminist point of view, thus focussing again on the public sphere.

Nightscapes (Atlas 4) examines the night as a space perceived as unsafe in the dark. Based on subjective experiences of women* on their everyday nocturnal routes, this atlas investigated which factors contribute to feelings of insecurity and compares those factors with the design rules of (urban) planning, which are thought to be objective. A taxonomy of nocturnal space types was created as a subjective safety catalogue of individually perceived factors and spatial conditions. As a change, a set of ideas was developed to illuminate nocturnal supply stations, influencing the sense of security or the assessment of the place by temporarily changing locations.

The research on Moving Through Berlin (Atlas 6) investigates how mobility options in Berlin are used by women* and how the existing mobility models shape women’s* mobility behaviour. The analysis shows movement patterns of a scattered everyday life, which illustrates the interaction between spatial and social living conditions in female biographies and mobility patterns. The result shows the extremely long distances that have to be covered in everyday life, whose spatial extension corresponds to the temporal extension represented by mobility patterns.

For a future non-sexist city, improved mobility conditions were envisaged. However, these improvements are not capable of eliminating the structural disadvantages underlying the mobility patterns and arising from other sectors.

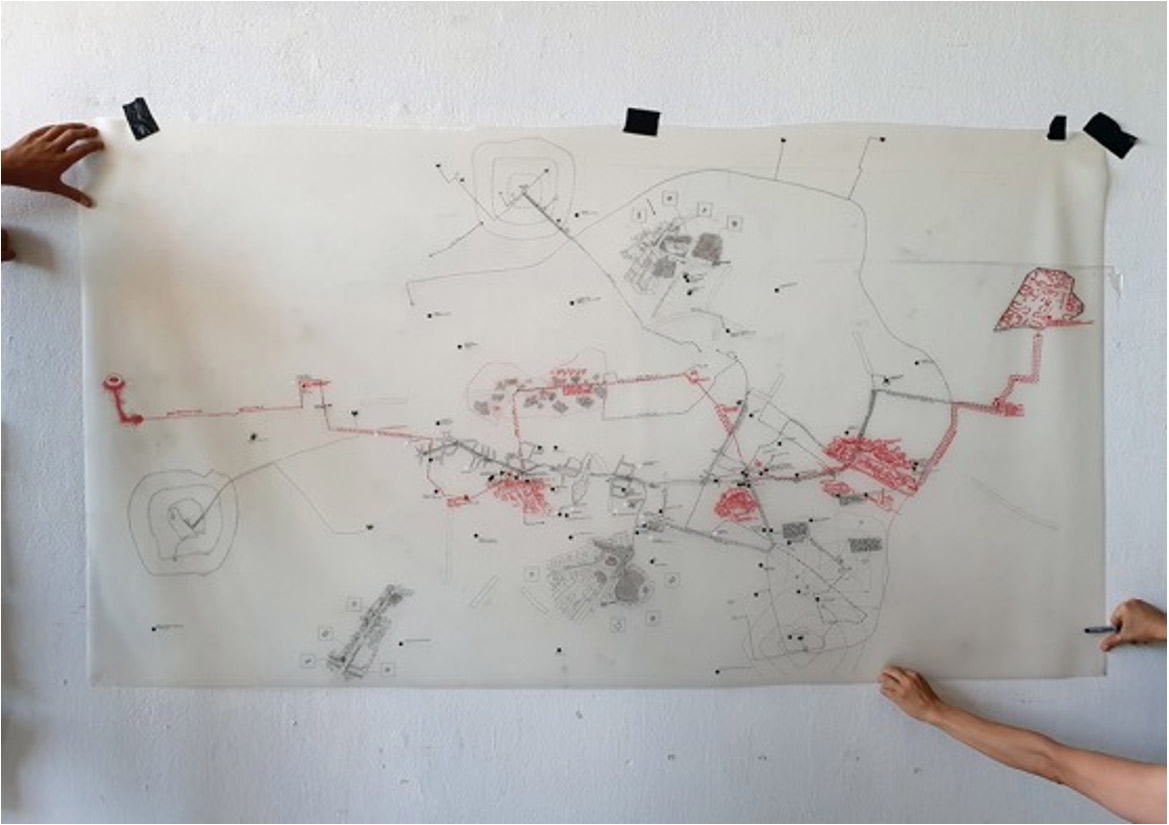

2.6. fem*MAP 2049

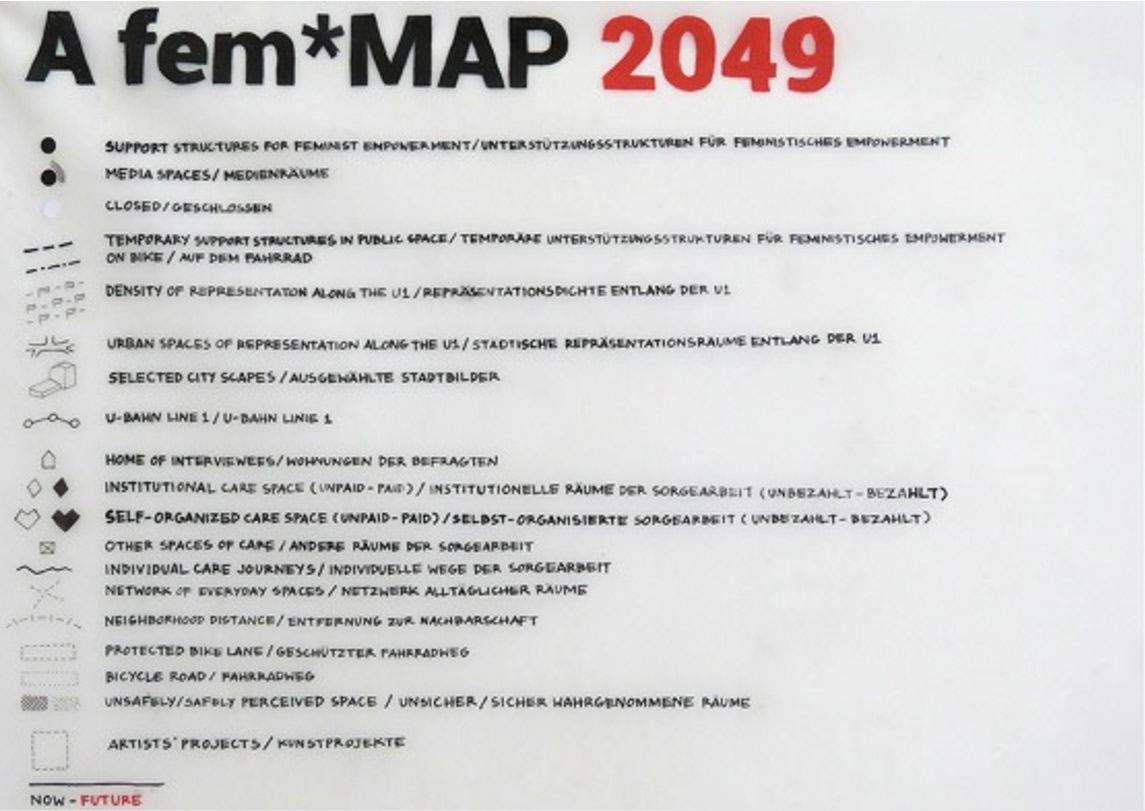

The results from the research seminar described above, which can be found in six of the eight thematic atlases, were integrated into a collectively created map of Berlin during the Mapping Camp. As an inventory of hegemonic and feminist spatial systems, identified based on the six artistic positions, a drawing was created with black lines, surfaces, and symbols as a snapshot of contemporary Berlin. The transformational potential identified in the research were translated into a red drawing, as a future image of Berlin, and superimposed onto the black drawing.

Without depicting a comprehensive map of the entire city, all elements from the previously described analyses can be found in the fragmented representation of Berlin. Thus, an infrastructure network consisting of part of the Ringbahn railway line, the U1 subway line, and several higher-level streets provides the basic orientation in the map and, at the same time, links the most important neighbourhoods studied in the city. Three different zoom-ins feature axonometric representations of selected neighbourhoods with shaded open space areas, including Tiergarten park. Three additional neighbourhoods are shown as mobility networks, representing caretaking sites differently organized. Selected street spaces and other open spaces are mapped along the U1 subway line together with locations of feminist support structures and zones with condensed feminist representation in urban space.

The future image of Berlin supplements this inventory using the same drawing symbols (but drawn in red) with new sites of representation, support for self-empowerment, institutions and care facilities, and areas illuminated at night in the open spaces. Three axonometric representations of completely new neighbourhoods extend along the U1 subway line, and a residential area far to the east of the city to incorporates Berlin's periphery into the future spatial system. The neighbourhood planned for women* forms the end point of a route running from the west across the entire city with numerous labelled places connected by this route in a future Berlin. The route is marked as fem*Festival 2049 and is described in an accompanying program text as a three-day march, which the students used to grasp the utopian moment of speculative mapping. This three-day narrative made it possible to connect the seminar's questioning of a non-sexist city directly to the contents of the drawing and to follow the festival train virtually and take a look at the future Berlin.

Thus, the fem*MAP 2049 simultaneously shows a present inventory and a future speculation of feminist spatial systems in Berlin based on concrete places, objects, zones, names, and events today and in the future. The description of the fem*March, which leads from the Olympic Stadium to the borough of Marzahn, was used as a tool to experience the spaces through drawing.

3. Discussion: synthesis by re-reading the mapping results

Re-reading the six thematic atlases and the and the collectively developed fem*MAP 2049 makes it possible to answer the three research questions formulated at the beginning of this article. The three questions build on each other in that the first focuses on the problematic situation of today, the second on an (im)possible future description of utopia, and the third on potential approaches to act in the context of the present. The research is used as a starting point for the mapping process, and the map itself acts as an independent graphic to interpret and synthesise the overall results. In doing so, we illustrate the potential of critical mapping (Harley, 1989; Wood, 1992) as an analytical tool for the (non)sexist city. This is because the map shows the hegemonic spatial systems of contemporary Berlin by revealing their deficits. In addition, the map provides feminist counter-designs for the patriarchally shaped city, highlighting cross-references between the different aspects of emancipatory spatial systems.

3.1. Hegemonic spatial systems in an unequal city

The question of which structural inequalities can be discerned in the concrete urban space is answered by the thematic atlases and the synthesis map using the drawing of the hegemonic spatial system.

Describing unequal spatial systems, including the user’s action level, produces a perspective that allows a new description of hegemonic spaces. This results from an integrated reading of the spatial condition and the corresponding restricted level of action. In order to grasp how a hegemonic spatial system can be described, the main theses from the research are summarized below.

Living space is described as a place with restricted access due to financial and spatial barriers, which despite its lockability and inaccessibility does not represent a safe place/shelter for all women* (locked front doors with unsecured room doors). Thus, the research on Gender-Specific Housing Conditions in Berlin (Atlas 5) clearly explains how the solidarity principle of the shared flat, as an originally emancipatory means of community housing, is being undermined by the scarcity of housing and how the privacy of the flat as a protective space is progressively dissolving in the process.

Caretaking spaces are often spaces that are intended for other uses and therefore are difficult to find and assign and come along with complicated habits of space use. Furthermore, these places expand into the public sphere due to a lack of spatial alternatives and are not sufficiently protected. The research on Places of Neighbourly Caretaking (Atlas 3) demonstrates that community caretaking is hardly visible in the discourse on caretaking to date but that it should be part of a future, feminist, empowering spatial system, which will require appropriate spaces and suitable infrastructures.

Practices of critical feminist representation can be seen as references to structural, economic, or social inequalities that manifest themselves in space through stickers, posters, or graffiti. Additionally, they highlight the invisibility of women* in public space, made visible only through non-established modes of spatial production using the tools mentioned above.

Meanwhile, the studies on Queer-Feminist Spaces of Empowerment (Atlas 2) and Remembrance, Representation, and Politics (Atlas 1) very clearly show that feminist spatial systems already exist in resistance to the sexist city. Their spatial and organizational function is often distinct from the hegemonic spatial system of the sexist city. By developing their own, non-sexist sets of rules, such as inclusive sanitary spaces or shelters for girls and women*, it is possible to establish connections between similarly functioning places that act as a network. Through the development of solidary and mutually supportive economic structures, these networks are also organizationally connected to feminist spatial systems and feature a similar spatial design. Yet, these spaces of empowerment remain places with precarious security, which can only be maintained through solidary (co-)financing. Through traces of critical feminist communication across various media, these networks find representation in the city and thus become visible. The spaces in which these media are effective and can be experienced thus become a materialization of the non-sexist city within the hegemonic spatial systems of the sexist city. In public space, a second layer is formed and superimposed onto the first in an emancipatory sense.

Finally, by superimposing the individual spaces of observation, the fem*MAP 2049 allows for a comprehensive analysis of urban spatial conditions. Here, the accumulation of structural spatial inequalities is revealed at the citywide level. For example, excessively long daily commutes for women* are related to the fact that care workspaces are improvised, outsourced to the public sphere, temporarily produced, or are located in inappropriate places. Thus, summarising the individual aspects and embedding them in the fem*MAP results in a perspective on established, sexist-structured spatial areas of the city in transition to the private spaces of care, empowerment, and living, which carry the political aspects of their oppressiveness, dissolution, and closure.

3.2. Non-sexist spatial systems as counter-designs to the unequal city

The feminist counter-designs to the patriarchally shaped city (Chapter 4.6) provide initial approaches for describing the transformative potential of different spatial areas. They offer answers to the question of what a non-sexist city could look like, and how the separation between public and private space can be overcome. Referring to the analysis results of gender housing, this separation could be overcome by collective forms of living, with common spaces and equal access to those spaces. Retreating into private space cannot be the answer to today's urban conditions of artificial scarcity and forced mobility. Only by securing non-violent spaces on the outside is it possible to retreat into the inside as a safe, private, and thus personal place (Arendt, 1960). Spaces of care need to be interconnected and programmatically complement each other, ensuring easy access through a flexible mobility network, and affordable caretaking spaces should be set up at the neighbourhood level. Stronger networking is also projected into the future for spaces of empowerment: for example, as curated space provisioning with densely arranged spaces that refer to each other.

However, the question of a feminist utopia at the level of the city as a whole can only be answered in fem*MAP 2049 by integrating and interweaving the transformative potential. To combine the different future potential for a non-sexist Berlin, the students* developed a narrative element (in the red layer of the map) anchored as a fictitious three-day fem*Festival and protest procession across Berlin on the map. Taking place in 2049, the march along the route from the far west to the far east provides multiple occasions to supplement the map with future spatial narratives (in red) from the eight thematic atlases. It passes numerous spaces of feminist history, self-empowerment, and representation that already exist today reinterprets those spaces for the future or as entirely new spaces. Doing so highlights the rarely told history of feminist achievements during the first- and second-women’s movements, and links these with current and possible future changes.

In addition, starting from subway line U1, the diverse manifestations, practices, and sites of self-empowering representation were interconnected and linked with the open spaces located along this linear spatial system. Thus, a network of night-time spaces also appears along subway line U1, supplemented by Tiergarten park, which builds a bridge to night-time spaces located farther away. The long routes of the neighbourhoods studied with a focus on mobility and caretaking also form an extension of the linear infrastructure of subway line U1 as a carrier of empowering practices and appropriations of space. In this context, a dense network of community-organised care spaces and support structures for feminist empowerment is drawn so as to differentiate the caretaking into places with paid and unpaid care, complementing the network of pathways, places, and spatial qualities around the city starting from subway line U1. These black and red places map a promise of the city to those who rely on such spaces, as well as to those who co-produce and maintain these spaces out of conviction and the desire for a different, non-sexist city. This densification and expansion of existing networks can be seen as a counter-image to the production of spatial inequalities in the hegemonic, sexist spatial system, reversing them into expanding and mutually reinforcing feminist spaces and networks.

Based on the tendencies already shown in the analysis of Gender-Specific Housing Conditions, the students developed a utopian neighbourhood in Marzahn (the only neighbourhood where, according to the survey, affordable and ‘safe’ housing was offered in 2020), as a translation of Berlin into a future city with better living conditions for women*. As a future perspective, following the argumentation, further self-managed islands of solidary coexistence emerge along the network extending from subway line U1, which are removed from the market-based housing supply.

In the considered hegemonically spatial fabric of the city, the public and the private are interpreted separately as spheres of productive and reproductive labour. By mapping feminist spatial systems, it became apparent that this dichotomy of private and public established in spatial studies no longer applies here. The mapped future feminist practices of the fem*MAP show that the use of interior, transitional, and exterior spaces can no longer be assigned to the categories of public and private, but rather eludes them, allows them to overlap, or subverts them. The expanding places of empowerment are ambivalent spaces: places of retreat into a shared ‘private’, yet places of shared ‘public’ within a particular community. The interior living space, in turn, can only become a protected, private refuge by securing housing as a public concern for all. The caretaking assigned either to the private sphere or managed by the private sector or communal agencies takes place within the feminist spatial system in self-organised community spaces beyond the public and private.

3.3. Conditions for the production of the feminist city

In order to answer the third question about the conditions for the production of feminist spaces, it is first necessary to address the issue of transformative practices of spatial production in the transition between hegemonic-established and feminist-utopian spatial systems. The future feminist spatial system shown on the map can be used as a basis to develop strategies for action in the present, demonstrating how a feminist perspective (on Berlin) could be developed today. Here, it helps to interpret the fictional spatial descriptions of fem*MAP 2049 as situated in a near future. If the spaces of the fem*MAP 2049 are not interpreted as a utopian place-where a non-sexist city has miraculously asserted itself against all patriarchal, market-based, and socially anchored structures and where urban political struggles are unnecessary-but rather as a field of conflict between resistant spatial practice and an unresolved overarching social problem. In this case, the map illustrates the transformational potential from the inventory of emancipatory spatial systems in today's Berlin, emphasising the importance of strengthening and safeguarding such fragile and unstable spatial productions.

New operating systems that allow for solidarity-based housing, make it easily accessible, and secure it in the long term are essential production practices for the feminist housing shown on the map. In order to ensure the networking and densification of care and empowerment spaces, this type of use must be anchored in commercial tenancy law and made available at affordable conditions for corresponding groups and initiatives, in part to counteract the disappearance of already existing places under increasing economic pressure. Feminist-oriented institutions have to be strengthened, and new ones have to be founded. Women* have to be represented in public space through monuments. At the same time, a different, equal image of public space has to be established in planning in order to achieve a gender-sensitive urban image among planning authorities. On the level of the city as a whole, existing networks must be consolidated, and formats of self-empowerment and representation have to be developed and tested. These could include festivals that temporarily test a feminist production of space at a city-wide level, as well as a variety of micro-formats, such as the installation of fem*MAP 2049 in the alpha nova & galerie futura, which represented a communal perspective on the city for one evening.

The practices of the feminist city can be described as communal creation. They represent a possibility to produce other and new forms of spaces: collectivised, networked, safe, and yet open spaces of inclusive and self-determined urban production.

The dichotomy of public and private is part of the hegemonic spatial system. Overcoming this dichotomy makes the feminist spatial system feasible and, in turn, provides for different degrees of communization to differentiate between diverse spatial uses. In order to describe and understand the feminist spatial systems, and thus allow for a different way of thinking and acting and the future design of these other spaces, we need to expand and refine this very vocabulary.

4. Conclusion: mapping as a tool to create counter-images

This article has illustrated the potential of critical mapping (Harley, 1989; Wood, 1992) as an analytical tool for the (non)sexist city by synthesising the mapping results. In order to make the method applicable to other studies, we will discuss the strengths and weaknesses of mapping as a means of spatial analysis and the chosen scope based on the example of Berlin.

The research illustrates the need to expand the scope of consideration beyond housing, as formulated at the beginning, to all urban spaces. The research topics in the thematic atlases, derived from the artistic positions of the exhibition, refer to diverse interfaces in urban space. This range of spatialisation in gender relations reveals the interconnections and interactions between the different spatial realms in particular. Nevertheless, the selection of spatial realms in this article is not exhaustive (as various other spatial realms and aspects could be investigated). Thus, even when incorporating the results of the research into the overall context of Berlin, the focus was not on broadening the mapping in the sense of a comprehensive view, but on compiling the still fragmentary approach feminist spatial systems into a coherent spatial picture.

Using the method of critical mapping (Harley, 1989; Wood, 1992) as an analytical tool made it possible to map both the inequalities inscribed in the spatial structures of our cities through social gender relations (Becker, 2008) and the existing feminist spatial systems and practices of resistance. Mapping was thus used as a tool to show the deficits of a patriarchally shaped spatial urban structure, as well as the potential of a feminist and solidary Berlin that integrates the needs of women* into spatial contexts.

The principle of making feminist spatial productions visible by ‘mapping otherwise’ (Awan, 2017, p.35)-for example, from a non-hegemonic perspective of the city-has three effects on the authors and readers. Firstly, the mapping serves to reveal the perspective of women* regarding urban space and the inequalities materialised therein. The map conveys this perspective to the reader by means of graphic codes and a legend, which suggests a non-hegemonic interpretation. Secondly, the map strengthens the perspective of emancipatory-feminist and thus inclusive, self-determined urban spatial production ensuring open spaces for everyone-beyond the hegemonic spatial production characterised by inequalities. Finally, mapping opens the view for potential futures by making the non-hegemonic and non-sexist view of space within the map the dominant graphic narrative, thus containing a ‘different’ tomorrow-derived from today.

Many of the spatial systems depicted on the fem*MAP 2049 can only be understood in combination with the thematic atlases due to the complex intertwining between materialised space and the way it is constituted through use and social frames of reference. Thus, the mapping process also reveals the limitations of the tool. The examination of interior spaces and private spheres could be depicted much less precisely than the spatial structures in the public sphere. Yet, it is precisely the mapping of the relationship between private and public spheres that is important to understand the materialised inequalities and the transformational potential in spaces.

The adherence to the scalar and projective approach of conventional cartography does limit the visualisation of all identified feminist spatial systems. However, it is precisely this adherence to certain hegemonic sign codes and conventions that makes the mapping of feminist spatial systems in Berlin comparable, and compatible, with our usual representations of urban spaces. Focusing on outdoor public space as opposed to indoor private spaces, which are difficult to represent, clearly illustrates the need for a feminist appropriation of the public sphere.

On the fem*MAP 2049, two spatial systems emerge very clearly that strongly refer to each other and in many cases are difficult to separate from each other: hegemonic spaces of a largely sexist city on the one hand, and counteractive spaces, in our case feminist, on the other.

The mapping of hegemonic spaces reveals inequalities that partly imply an explicit exclusion of women* but mostly have structurally implicit causes, such as the dark Tiergarten park at night or the long routes to day care centres. Several forms of oppression are intermingled here and require an intersectional perspective. However, part of the hegemonic spatial system is also the lack of spaces that serve self-organised or non-commercial everyday practices such as solidarity-based caretaking. The mapping and analysis of explicitly feminist spatial systems reveals an emancipatory potential for self-empowerment in the public sphere, as well as the possibilities of spaces of self-organisation and solidarity to impact the private sphere and beyond.

The fact that the relations under which the city is produced change the inequalities is crucial for a feminist turn. Above all, this entails communitarian notions of ownership beyond the dichotomy of public and private. It refers to other, non-profit economies of shared returns and other notions of architecture that include not only materiality but also use, in which preservation, care, and protection are central. This requires multiple perspectives in decision-making processes, the inclusion of subjective experiences, and diverse spaces that allow for both specific and integrative uses. Furthermore, it means eliminating the gendered dualistic division of labour into paid productive work and unpaid reproductive work. It means securing space for those who live and work in it versus those who invest capital in it. It means adopting an attitude of solidarity towards those for whom the scarcity of spatial resources is the greatest burden, who lose shelter in the process, and who can no longer find places of their own.

Therefore, the non-feminist city is a struggle for a self-determined and inclusive use of space based on economic redistribution and communal protection to guarantee that everyone is provided with urban resources-the social, economic, and ecological benefits of the city.