Foreword

In October 2021, shortly before I finished this essay, I finally had the chance to revisit Malmberget after 1.5 years of high COVID numbers. COVID has kept me away from the town and local research friends, but online activities have maintained, and maybe even strengthened, the connections to the feminist practitioners that I will introduce in this paper. In Malmberget I was blown away by what had happened since my last visit. In some places, not much was left of the town, with 73% of the Eastern part taken away (Gällivare kommun, 2021). I was not even able to orientate myself between the gardens and streets without houses. Pernilla Fagerlönn and I went through the deserted area, where empty areas of just mud had replaced the houses; even the streets had been partly taken away. Looking at the forlorn gardens, a pie plant was waiting to be harvested. Behind the fence, piles of building material, furniture, and walls had been crushed by machines. On the other side of the huge pit, the only high-rise building of the town had been dismantled and transformed into a pile of earth mixed with building parts. The metal reinforcement of the concrete was visible from behind the fence, next to spiral staircases, heaters… The blue colour of the paint of the concrete wall, which had separated the building site from the street, was recognizable on small parts in the midst of the pile. And yet the town was alive, with cars parked near the piles of building parts, a bandy game taking place in the remaining sports hall, and inhabitants still living in the house next to the supermarket, which had closed a while ago. And myriad birds occupied the houses waiting to be dismantled and filled the acoustic space - their chirping could not be fenced off.

In extractive territories, companies determine most aspects of local areas, from the scale of global material flows, shared environments, and urban transformations to the scale of daily lives and cultural events. With my observations from two mining communities, I aim to foreground feminist actors who apply spatial practices of care, support, maintenance, and reproduction. They are often excluded from direct salaries of extraction, and yet they are highly relevant for the endurance of the communities necessary for extraction. Two goals frame my observations of, and engagement in, two specific mining communities: (1) drawing attention to feminist actors’ reparative and counter-extractive practices as forms of shared architectural interventions; and (2) developing and providing situated knowledges together with a material positionality in relation to extraction as a requirement for architectural production based on the material of iron ore. These located aims rely on the ontologies of two sites, which are the starting points for knowledge production and also destinations of the produced knowledges.

In recent years I have had the opportunity to learn from two extractive towns, both relying on the extraction of iron ore. The first town that formed part of my fieldwork from 2016 is Malmberget (literally ‘ore mountain’), in the north of Sweden, which will eventually disappear as a result of the expansion of mining. Malmberget also lies in Sápmi, and the Indigenous Sami people, and their naturalcultural1 life-ways, have often been forced to make way for mining and further industrial exploitation of Sweden’s North (Sehlin Macneil, 2017 and 2018; Öhman, 2017; Össbo, 2020). Since 2019 I have also been working with the town of Eisenerz at the foot of the mountain Erzberg (also meaning ‘ore mountain’), in the Austrian Alps, which is likewise in a crisis of identification, over-ageing, and shrinking, because mining requires less and less of a human workforce. Both communities are situated in remote positions. Malmberget lies in the rather sparsely populated area of Northern Sweden, Norrbotten, and also, prior to that, in Sápmi, the land of the Indigenous Sami. Eisenerz lies in the Austrian Alps, reachable via a mountain pass more than 1,200m above sea level. Both communities have left their ‘golden eras’ - with more than 10,000 inhabitants - behind, while ore is still being exploited today. However, different reasons apply to each of the communities: Eisenerz requires a diminishing workforce because of the high degree of mechanization; and Malmberget’s ground has become unstable because of the progression of underground mining. Therefore, areas of Malmberget are declared rasriskområde (landslide risk areas), people are resettled, or they leave the area altogether.

Both communities are in search of new narratives for post-extractive futures, because the resources will expire in a couple of decades. Therefore, I argue for architectural research methodologies that ‘observe’ differently, foregrounding alternative actors, their feminist ecologies, and their productive spaces. Learning from actors such as the women of the local Embroidery Café, who embroider architectures soon to be lost, or like Pernilla Fagerlönn, who curated a farewell event for architectures, or Miriam Vikman, who preserves the colours of facades in paintings. Furthermore, my work draws on my experience of actively participating in their processes and numerous conversations, which informs the argument that the field of extraction is diverse, and also full of pleasure and creativity (Reisinger, 2021). Critical agencies of feminist spatial practices2 respond to patriarchal extractive practices. For future scenarios of the coming transformations of both environments, I suggest activating these situated knowledges with alternative methods of producing and sharing knowledges. With all of this, I aim to contribute to feminist visions for post-extractive environments.

Towards a material positionality for researchers in architecture

Thus, the central question remains what ‘we’ as researchers of the extended fields of architectural humanities can offer these areas in crisis. I refer to research that is not bound to offices in academia but which connects, collaborates, and contributes to the ‘real-life-worlds’ of actors who maintain and care instead of extracting and dismantling.

First, I suggest being aware of one’s own relational position, or giving account of oneself3, trying to sense ways of interrelatedness on many levels - and of the relationships and positionalities that evolve (Rowe, 2014, p. 628). The researcher is never in control of all the factors that determine the relationships4. I want to borrow the term positionality from the methodology of ‘action research’, which David Coghlan and Mary Brydon-Miller (2014, p. xxv) define as “integrat[ing] theory and action with the goal of addressing important organizational, community and social issues together with those who experience them”. Their definition gives ample scope to the issues to be supported by theory and action but urges a rethinking of the collaboration between researchers and the local actors who are the experts. One way of doing this is considering different options of positionality. Between the researcher as outsider and insider, there is a wide range of power relations of possible collaboration (see Rowe, 2014, p. 627; Herr and Anderson, 2005). I am clearly an outsider in Malmberget and Eisenerz - and the separations of COVID have strengthened that distance - but I continuously strive for reciprocal relationships with the people of the communities, coming together on equal terms and working together with a great awareness of the dependence of research on the ongoing generosity of the local actors.

Positionality refers to the stance or positioning of the researcher in relation to the social and political context of the study - the community, the organization or the participant group. The position adopted by a researcher affects every phase of the research process, from the way the question or problem is initially constructed, designed and conducted to how others are invited to participate, the ways in which knowledge is constructed and acted on and, finally, the ways in which outcomes are disseminated and published. (Rowe, 2014, p. 627)

In that regard, my research questions are constantly being revised. How knowledge is produced is dependent on local actors, and outcomes are disseminated back to the communities in formats that are welcomed by them. Therefore, durable connections are highly relevant - ‘we’ architectural researchers are all too used to quickly moving from context to context, from region to region, and from town to town5. Instead, continuous research in peripheral zones of material extraction in collaboration with feminist actors demands self-positioning, critically reflecting the power relationships between areas of ore extraction and towns of steel construction. The latter is also where knowledge production is settled.

Material can serve as a way of looking at relationships of power. In the profession of architecture, we build towns and cities with the products of ore extraction; furthermore, the computers used for design and communication rely on the exploitation of mineral resources. This paper is written on a laptop, which is based on minerals. The paper was also streamed at a conference with the help of mineral resources, which are indispensable for our connective practices of writing, speaking, and listening. With this connection, periphery and centre are connected: the margins are created by the centres, just as agriculture is determined by the cities that it supplies. They need to be analysed in relation to one another. The material from the depths of the mountains is shipped globally to bring opportunities for many but leads to loss, problems, and limitations for those losing their homes as a result of their mountains being taken down or perforated (see also Reisinger, 2021). This is the spatial power field of extraction, operating globally and locally at the same time. The profession of architecture is interdependent and involved in situations of inequality, and ethical research practices need to be enriched by an awareness of the entanglement in material connections, which are also connections of power.

In this regard, we can learn from feminist new materialisms: “Consider a phone contributed from metal, frequently mined at the expense of violent racialized human labour and Indigenous sovereign rights over land”, Sarah E. Truman (2019) invites us to think. Likewise, architecture is imbricated in capitalism, economy, and exploitation, creating a certain environment for people who live at the sites of extraction, again supported by architectural and infrastructural facilities onsite.

Seeing with local practitioners and their knowledges

How we know about material in architecture rarely includes a social dimension of the extractive zones of our world. How can we produce situated and located knowledges, especially when material is mobilized throughout the world? Donna Haraway’s highly influential paper, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’ (1988), complements Harding’s Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader (2004)6. Haraway’s paper, published in 1988, created a stir, first in the humanities and then slowly seeping into the architectural humanities. It has influenced many feminist eco-thinkers in architecture. Hélène Frichot (2019, p. 132) describes situated knowledges as “celebrating diverse feminist formations of knowledge where a necessarily partial and fragmentary situation is acknowledged, but one still adequate to make a rich account of a world”.

“Feminist objectivity means quite simply situated knowledges” - this is how Haraway (1988, p. 581) describes her “doctrine of embodied objectivity that accommodates paradoxical and critical feminist science projects”. A myriad of interrelated approaches to how this ‘feminist objectivity’ was to be reached, fundamentally ground-breaking in 1988, continues in recent methodologies of architectural practice and theory, and mostly in projects that cannot be put into one of these categories alone. Haraway’s paper works against the binary of subject and object, for located, embodied, and situated knowledges. She insists “on irreducible difference and radical multiplicity of local knowledges” with dangerous, necessary, and contradictory combinations (1988, p. 579). “In the encounters procured between the subject in formation and her seething environment-world, the power of feminist-situated knowledges emerges”, Frichot (2019, p. 132) outlines, considering the sympoietic trajectories of Haraway’s thinking with situated knowledges (Haraway, 2016).

Haraway also offers an approach to vision as an embodied and complex concept with the capability to work against binary oppositions (1988, p. 581), which is crucial - together with the work of further feminist thinkers - for my approach on areas wrongly considered peripheries. This approach includes being aware and transparent about the perspective and the technologies of knowledge production and dissemination, which have everything to do with our material and thus social entanglements. With the framework of situated knowledges, architectural research becomes able to sense, and make sense of, many, and unexpected, practices. The knowledges produced are manifold and contradictory. They have cracks and fissures (see also Harcourt and Nelson, 2015).

Looking for feminist actors in zones of extraction requires a durational engagement in a creative and rich field of feminist activities of reproduction and care amongst extraction, as well as creative and visionary practices to respond. This work asks - besides the powerful mining actors and companies: Who are the actors capable of dealing with the loss and understanding living well together, also in the future when the mineral resources run out? In that regard, I am most interested in actors who contribute to society with their activities of care and support - often feminist cultural practices that are full of futurities and situated knowledges for colonized and racialized extractive environments. To approximate what Sarah E. Truman has claimed from feminist new materialisms, namely, a “feminism that attends to race, gender, sexuality, and ability” (2019), I want to borrow Macarena Gomez Barris’ feminist and decolonial knowledges on extractive zones of the Americas. She speaks of ‘submerged perspectives’:

These submerged perspectives are anchored within social ecologies that reorganize and refute the monocultural imperative, as do I in my encounter with these other worlds. Submerged modes flurry in their activity, random, complex, and coordinated systems that are often illegible to those with state and financial power that assume simplicity where complexity actually dwells. (Gómez-Barris, 2017, p. xvi)

The local actors that I have been working with have created rich, ‘random, complex, and coordinated systems’ (ibid.), which are not easy to comprehend, but which I have the honour to join, and also the privilege to leave, whereas the actors stay in their extractive zones.

Centring sympoietic research relationships between myself, the researcher, and specific actors of the communities I work with, how can researchers and researched subjects ‘observe’ and ‘participate’ differently? I, as researcher, and the people I work with research one another - we are interested in one another’s work. In 2017 Karina Jarrett founded the Embroidery Café of Gällivare-Malmberget. In the monthly gatherings Margit Anttila, Berit Backe, Carina Engelmark, Eeva Linder, Karina Jarrett, and Christine Madsén Andersson come together to exchange stories and experiences, while they embroider together. Their works have been exhibited in Sweden and elsewhere. Also, they document the disappearance of the town of Malmberget, a sad process for the long-term inhabitants of the town, especially Margit Anttila, who has spent decades of her life there (Jarrett and Reisinger, 2021).

One of my most successful moments was when Karina Jarrett described my involvement in the Embroidery Café as an ‘inspiratör’ to a local newspaper (Östling, 2019), addressing the architectural motives of their embroideries. I had provided them with architectural material about the disappearing architectures of Malmberget, which lay underground in the Collections of ArkDes, Sweden’s national centre for architecture and design in Stockholm. Some of the drawings by the architects Folke Hederus and Hakan Ahlberg had made it into the embroideries (Reisinger, forthcoming)7. Is this connective acting with shared output of the researcher and ‘the researched’ still a way of observing8? In view of a long tradition of feminist critique of neutral / objective / apolitical ‘observation’ (Haraway, 1988; Harding, 2004; Llewelyn, 2007) I would like to highlight a footnote by Sandra Harding from 1993 (p. 468):

Some marginal people must be able to observe what those at the centre do, some marginal voices must be able to catch the attention of those at the centre, and some people at the centre must be intimate enough with the lives of the marginalized to be able to think how social life works from the perspective of their lives.

Harding has, unveiling relevant relationships of centre and periphery, claimed radical foregrounding and making accessible the knowledge production of the usually ‘observed peripheries’.

Activating knowledges and feminist visions for post-extractive environments

What can an active feminist enquiry in extractive areas do, acknowledging that we (researchers) are part of extraction while writing on our laptops, streaming online presentations, connecting virtually for hours, and using laptops to read this essay, for example? A central feminist question, including all local intersectionalities, is still: Whose is the knowledge anyway? And for whom is it useful? How can we researchers in architecture create relevant and accessible knowledges that respond to situations at the margins and becomes criticizable there, in conversation, publications, and collaboration? Research mobilizes perspectives and values in the best case. However, this is not free of risk of strengthening or creating new hierarchies. Nevertheless, a central aim of my research is to strengthen the positions of the margins, at the same time initiating self-critique at the centres.

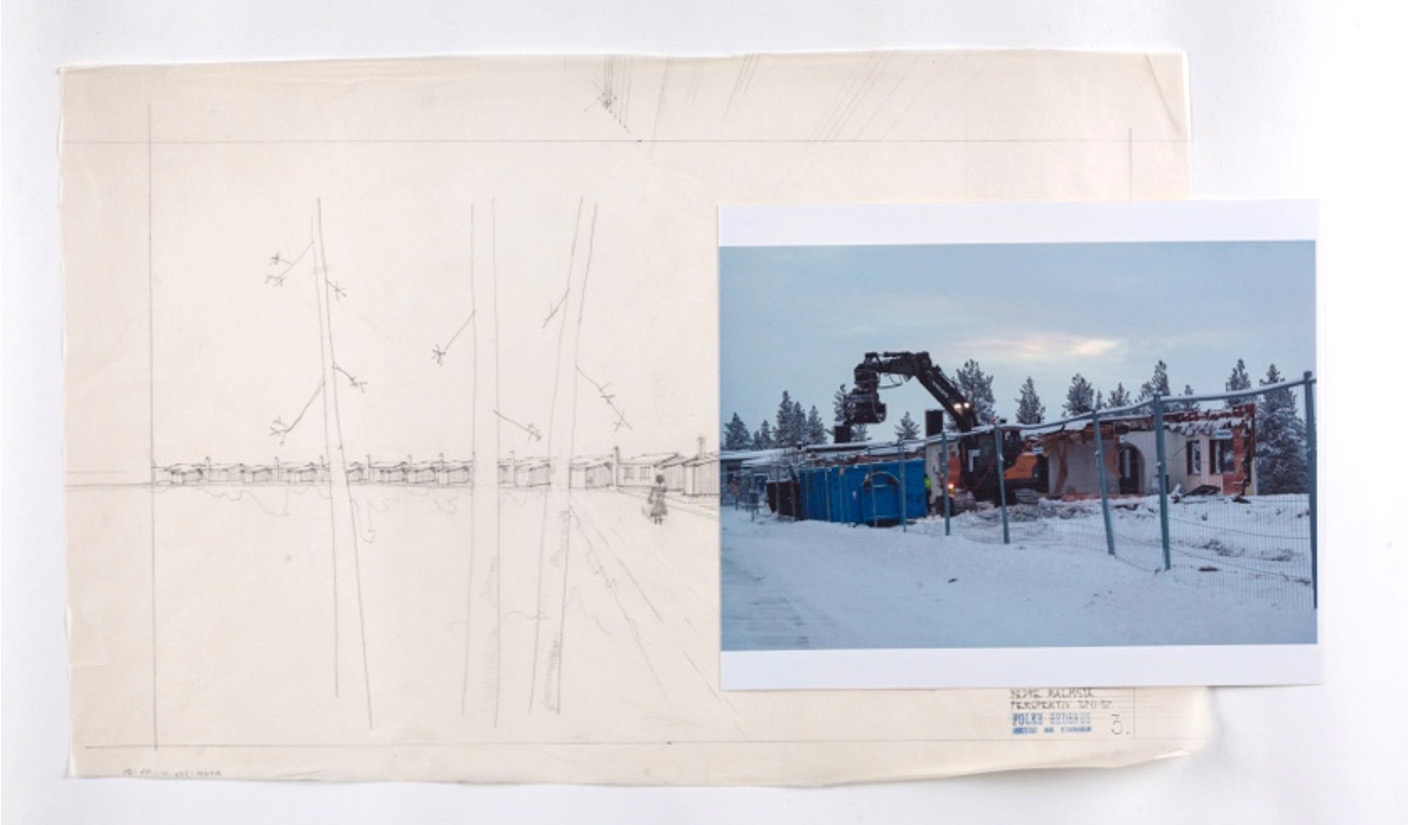

Reisinger, 2018 (drawing by Folke Hederus 1957)

Björn Strömfeldt

Figure 2 Lifelike Appendix to the Archive No. 1

In January 2019 I gave a participatory lecture at Folketshus Gällivare, the neighbouring town of the slowly disappearing Malmberget. For, and together with, the people who inhabit the architectures before they are dismantled, the architectural findings about these houses were shared. The event created some unusual situations, with inhabitants seeing the architectural qualities of their houses projected on the wall, as drawings from architectural archives. They were able to add to the details, and appreciation of the architectures was acknowledged as part of the local process of mourning.

In the same year I added the images of the destruction of Malmberget to the unpolluted and formerly visionary drawings of the ArkDes Collections as a Lifelike Appendix to the Archive (Reisinger, forthcoming) to enable researchers from various countries to see what is actually happening to the architectures they study: they are being dismantled.

Instead of knowledge activism9 I prefer the word ‘knowledge activation’. A central concern of my work is activating submerged knowledges, bringing forth how the margins see the centre, making knowledges accessible, and unveiling co-productions of knowledges (Jarrett and Reisinger, 2021; Reisinger and Jarrett, 2021), discussing with the people at the ‘margins’ (and at the same time the material centres) how the knowledge in the ‘centres’ is produced. On its own, the notion that knowledge margins are material centres, points of origin, contributes to shifting “the centre from which knowledge is created” (Reid and Gillberg, 2014, p. 344) to create an openness for building “multiple feminist theories rather than a ‘grand narrative’ that captures the experience of all girls and women” (ibid., p. 345), or all Indigenous persons, or all immigrants. Addressing the many voices of submerged knowledges is particularly relevant for my case studies, since the material riches have always attracted people from many parts of the world, while also exploiting and expelling people.

Within the complexities and risks of seeing with local practitioners and their knowledges to find ways of doing material positionality, I aim for imaginative politics and visionary forces as, maybe, the only way out of extractive relations. Coming back to my long-term commitment to working with the disappearing town of Malmberget, and having also started working with Eisenerz, Erzberg, I want to show that the dependence on heroic, extractive practices is only a partial reality. It has already been complemented by many feminist spatial practices, supportive, repairing, caring, maintaining, creative, and thus critical all along. Pernilla Fagerlönn curated the farewell festival Farväl focus for Focushuset, the last-remaining high-rise building of Malmberget, with local artists. Miriam Vikman paints in the colours of the facades of the dismantled houses, and the Embroidery Café continues to develop its artworks between pedagogy, care, and living well together. Their work is exhibited in more and more exhibitions in Sweden and abroad. Also, in Eisenerz in Austria, cultural practices of care operate amid an area dedicated to extraction. Karin Hojak Talaber (2021) researches, exhibits, and publishes the work of female miners. The exhibition takes place in Gerhild Illmaier’s FreiRaum in the centre of the town with many abandoned properties.

Top left: Pernilla Fagerlönn’s participatory sculpture at the Farväl focus festival (2019). Photo: Pernilla Fagerlönn. The visitors were invited to share their emotions about the dismantling of the Focushuset by choosing different ribbons; Top right: Karina Jarrett, Insekterna flyttar in / The Insects Move in, embroidery. Photo: Karina Jarrett. The insects move into the houses that have been abandoned by humans; Bottom left: Margit Anttilla, embroidery. Photo: Karina Jarrett; Bottom right: Allt som lever är förgängligt, om nåt kunde vara evigt / Every Living Thing Perishes, if only there was some Things Eternal, 150 x 120cm, painting of a façade by Miriam Vikman, reflecting the colours of architectures that no longer exist in Malmberget. Photo: Reisinger (2019).

Figure 3 Feminist visions for a post-extractive environment

This is all about the future. The two communities of Malmberget and Eisenerz have trouble articulating their future visions: Malmberget will disappear in the coming decades, architecturally unbuilt, banned to the architectural archives. Eisenerz is shrinking and the community has the highest average age of the state. Both lack vision about how to live without mining. The end of mining is a pressing and very uncomfortable question for both communities. Possible futures need to be created, to borrow Rosi Braidotti’s (2012, p. 36) words, “by mobilizing resources and visions that have been left untapped and by actualizing them in daily practices of interconnection with others”. Learning from numerous conversations and from shared processes with local practitioners is a privilege that is dependent on their generosity and raises questions of how architectural research could respond to large problems such as losing one’s home. Learning from their knowledges in active forms of collaboration is, I think, what we need to practise in research to oppose the capitalist advancement and ruination of our environments.

Some concluding thoughts on research in extractive areas

With this paper, I hope to have offered a modest insight into knowledge struggles and processes of learning and some methodological ways that emerged during that process, again co-determined by local practitioners. By my active involvement in the practices of exhibiting, embroidering, and publishing, and of transferring knowledges and making them accessible and productive in various creative practices, and with the co-production of knowledges in multiple formations, my research aims to develop an alternative to research as extraction. This leads to a continuous dialogic process that has, in fragments, been shared in this paper. It cannot draw back to generalizable outcomes because the collaborations are specific and dependent on situations and possibilities. It is also difficult to name one method or a specific and constant setting of material. Rather, this research opens up for a mosaic of various small-scale impacts that emerge in collaboration with local actors, respond to grounded ontologies, and make use of the various skills of an architectural education. The aim is to interact and create, if welcomed by local actors. In the course of this process, theories and practices are imbricated, entangled - neither separate nor separable. They are part of an ongoing process, which is also an ongoing formation of a method that is open to change to integrate and build on unexpected encounters and situations. This is especially important amid the extraction, climate change, and further complications of our time that we more-than-humans face.

Acknowledgements

I am thankful to the fabulous feminist practitioners of Malmberget, Gällivare, and Eisenerz for keeping so many important connections vivid, especially to Pernilla Fagerlönn for giving lectures together and for discussing this paper. This paper was written with the support of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): project no. T1157-G.