1. Introduction

Street cleaning in Madrid was a privately provided service from its beginnings until the end of the 19th century when it was municipalised and the service was transferred to public provision and management. This article studies the first and only privatisation (public provision with private management) that has taken place in this basic service and the explanatory factors and movements of each actor behind this decision from the mid-1970s to the end of the 1990s.

The problem of waste management has always been with mankind. One of the elements that helped to raise awareness of the need to take action in cleaning up cities was the French and English hygienist movement in the 18th and early 19th centuries (Ramos Gorostiza, 2014). Until then, waste management was very scarce and short-sighted, with a commitment to evacuate waste from cities, moving it outside their boundaries due to the health risks inherent in its indiscriminate accumulation.

But the problem of public cleaning continued to exist since there was the possibility that one or more individuals would not comply with the general criterion of depositing or delivering waste to a collection cart (ragman, collector, transporter...) that could dump it in the place intended for this use. As a consequence, the need for a street cleaning service arose. Street cleaning is recognised as the combination of different techniques, manual, mechanical or mixed, which are repeated whenever necessary, adjusting them to the needs of the city at any given time. The actions are carried out on public roads (pavements and carriageways) owned by the municipality (not including cleaning actions carried out in green areas)1.

The evolution of the cleaning service from its beginnings had as main elements, as Pérez Ramírez (2016) argues, administrative schemes that favoured clientelism and corruption. With the increase in fiscal pressure, the sale of public resources and positions in Spain was resorted to, which led to the concentration of a large number of municipal positions in an oligarchy. (González Enciso & Matés Barco, 2013). This led to a form of mercantilism (Ekelund & Tollison, 1981) in which concessions were sold in exchange for favours. In this way, as Naredo (2019) says, the purpose of service provision became a mere pretext for making profits at different stages of the process, creating serious ecological problems. In effect, institutions and habits were moulded in such a way that ‘vicious passions’ fed back, removing moral censures of unsupportive behaviour. As she warned (Arendt, 1996), when wealth becomes the end to be achieved, politics and the public sphere become means to preserve the interests of wealth accumulation (Delgado & del Moral, 2016). The positions, achieved by chance, led to the colonisation of public spaces with no thought for the social good (Albi, 2017), which has undermined our idea of community. (Marglin, 2008).

On the other hand, the privatisation of street cleaning in Madrid does not escape the general context of privatisations that took place in the 1990s. Neoliberalism is imposed as a political agenda (Streeck & Thelen, 2005) and is implemented through rounds of regulatory restructuring with regional differences. The essential objectives will be the “intensification of the rule of the market” and the “commodification of society”, implemented through various phases in a wave of regulatory changes that will end up modifying the global economy. (Navarrete-Hernández & Toro, 2019).

Three periods have been identified as defining the urban neoliberal process (Navarrete-Hernández & Toro, 2019) (Brenner & Theodore, 2002). First, during the 1970s the advanced industrial economies, it consisted of dismantling existing state-led Fordist-Keynesian structures and imposing new structures aimed at boosting growth and reducing inflation through free-market reforms (Peck & Theodore, 2007). Secondly, during the 1980s, neoliberal pro-market policies (privatisation, deregulation and welfare reduction) were developed, introducing austerity and inflation reduction measures. (Ferrando, 2008) introducing austerity measures and reducing production costs in public management activities. In the third period, from the 1990s onwards, neoliberalism is modified to become a consolidated and long-established solution. (Harvey, 2007).

In essence, street cleaning in Madrid will be subject, on the one hand, to the evolution of systems whose purpose is not the quality or provision of the service but rather to make a profit at different stages of the process and, on the other hand, to the international neoliberal situation that modifies the context of municipal management, generating dynamics that facilitate the privatisation of services.

2. Object of study

For the above reasons, and for this article, we will focus on the privatisation of the street cleaning service in Madrid. The definition of street cleaning is based on the concept of public service. Falla (1994) defines this concept in Spanish law; here, however, we will see that the transfer of the management of the service to privately owned and capitalised companies lead to the concept of public service being distorted.

Street cleaning in Madrid has gone through 3 stages:

i. a privately provided service from its beginnings until the end of the 19th century;

ii. A stage of municipal provision and management that occurred after various problems and, as mentioned in the introduction, generated a multitude of corruption systems during its previous stage of private management. Faced with a situation of paralysis in the cleaning service resulting from an auction of the service carried out in 1894 (Biblioteca Histórica de Madrid F 3249) and in anticipation of not a few corrupt practices between the contractors and the public administration, an oral trial was opened in the Audiencia de Madrid against 18 councillors (Biblioteca Histórica de Madrid F 7236). Finally, on 20 July 1897, during this judicial process, for the first time in the history of the street cleaning service in Madrid, the service was transferred from private to public management. The circumstances and patterns that led to the municipalisation of Madrid’s street cleaning service can be classified as a non-exhaustive list of elements that had been recurrent in the capital in previous periods: (a) a growing tension between concessionaires and consumers of the service, (b) an unsuccessful attempt to regulate and supervise the services, (c) epidemics due to lack of sanitation, (d) the existence of corruption between cleaning contractors and contractors (Arribas Cámara, 2019). Many of these circumstances had been experienced before in other European capitals such as Brussels, Berlin or Rotterdam (Chicote, 1906). This was not the only service municipalised at this time, the Madrid bakery service in 1905 (Magaldi, 2017) or the slaughterhouse and market services were in the same situation at that time (Magaldi, 2012);

iii. A new stage of private provision that continues to the present day after the privatisation of the service during the 1990s.

In this article, we will focus on the latter stage and, therefore, study the first and only privatisation that has taken place in the history of this service.

3. Hypothesis

Hypothesis 1: The privatisation of the street cleaning service in Madrid during the 1990s was not due to a malfunctioning of the municipal management of the service, but was the result of previous planning.

Sub-hypothesis 1. If the first hypothesis is correct, privatisation planning included the use of various exogenous mechanisms to generate a need for the privatisation of the service.

Sub-hypothesis 2. The political ideology of the municipal government does not make a clear distinction in the decision to privatise.

Hypothesis 2: The privatisation of Madrid's street cleaning service resulted in a reduction in the quality of working conditions of the service's employees.

4. Structure

This article is divided into 5 sections. The first part shows an introductory framework with the evolution of street cleaning in Madrid from its beginnings to its municipalisation. The second section refers to the first stage of privatisation 1975-1980 and analyses the economic situation and a series of reforms that affected the street cleaning service in Madrid, such as the new labour relations model, the modification of the institutional framework and economic development, which marked the end of this decade. The third part, the second stage of privatisation from 1980 to 1990, analyses the first steps of democracy in the municipality of Madrid. This is a vitally important stage as it represents the planning and first steps in the implementation of a private management model for the cleaning service. The fourth section covers the last stage of privatisation (1990-2000) and will delve into the factors that explain the consolidation of the privatisation of the service, the development of actions that lead to its definitive implementation and the first years with the new type of management of the activity. Finally, it analyses whether the hypothesis put forward is fulfilled together with its respective sub-hypotheses.

5. Street cleaning in Madrid: an introductory framework of the service. Why was Madrid's street cleaning service municipal?

The research question of this article aims to analyse the privatisation of the street cleaning service in Madrid. For privatisation to take place, the service must be publicly managed and, therefore, it is necessary to explain briefly, as this is not the subject of this article, how the street cleaning service came into being and how its municipalisation came about.

Madrid was a small town with sufficient resources to deal with the incipient problems of urban hygiene. From 1496 onwards, the obligation of residents to keep the front of their houses clean was formalised, and they also assumed the economic costs of these actions (Rubio Pardo, 1979)2. In 1531, the mayor, Antonio Vázquez de Cepeda, decided to auction street sweeping for the first time to various obligated parties (individuals or legal entities that carried out the street cleaning service in a section of the city). Since 1561, the municipal government resided in the Town Council and the Sala de Alcaldes de Casa Corte. They were therefore responsible for the cleanliness of public spaces (as in having the duty to provide cleaning service). Because of the above, it seems very likely that the creation of the Ramo de limpieza and the start of the sweepers’ professional service was at a date close to those mentioned above. (Blasco Esquivias, 1998)

The cleaning service was initiated after a public auction by the Madrid City Council. The auction was carried out by quarters (districts) and for a fixed period of time. (Blasco Esquivias, 1998)3. The municipalisation of the cleaning service in Madrid was introduced in 1897 due to interrelationships between economic and political power that are very common in the history of Spain (Rubio-Mondéjar, 2018) (Rubio-Mondéjar & Garrués-Irurzun, 2016), (Preston, 2019) subjecting the service to foreign interests and a lack of administrative foresight. Moreover, the determination to municipalise had a favourable international framework (Chicote, 1906).

Street cleaning in Madrid was a municipally managed and provided service from 1897 until its privatisation in the 1990s.

Briefly, as argued by Arribas Cámara and Trincado Aznar (2021), the most substantial changes in the first stages of the public service were: an increase in the number of workers, an awareness of Madrid’s neighbours for keeping the streets clean, an increase in investment in the improvement of immaterial and material working conditions, an increase in the institutionalisation of the cleaning service, and an improvement in the investment in fixed capital.

If we look at the report on the management of the Madrid City Council from July 1909 to September 1911, referring to the state of the service inherited from private management, the breakdown of the staff that made up the street cleaning of Madrid stands out with 984 people (including head of the service, workshop staff, various trades such as teachers etc), as well as 24 carts of various sizes, 500 brooms, 162 mules and mules, 130 iron shovels, 238 wheelbarrows or hand carts. It is noted that the above-mentioned personnel is insufficient for the execution of the service on 5 million square metres of public roads. Each of those is assigned to sweep areas of 14,000 square metres and therefore the service is not carried out daily, with the service being effective in most areas only once every 8 to 15 days.

Subsequently, in 1914, a major investment was made in the street cleaning service with a comprehensive reorganisation of the service and the construction of work centres in Madrid (these centres continue to provide the service to this day). This reorganisation, together with subsequent modifications to the municipal cleaning regulations, gave the cleaning service the working model that would last until the end of the 1970s.

Antonio Arenas Ramos, the chief engineer of the cleaning service, issued a report on the improvements achieved between 1914 and 1918. In this report, several aspects should be highlighted. Firstly, regarding the personnel, he points out that a total of 169 cleaning workers were assigned to each area of Madrid, of which 24 were on weekly rotational rest, 5% were absent due to illness and 2.40% were absent without justification, with the corresponding deduction from their salaries. Secondly, the lack of personnel is criticised, both in terms of cleaning operatives and foremen, with the latter being so few in number that they have to cover the posts for the whole of Madrid by rotating between them, and therefore the management of the different teams of workers is no longer taken care of. Finally, as well as drawing attention to the completely deficient uniforms of the personnel, he mentions the existence of workers under 16 years of age (llaveros) who, both because of their age and the hardness of the work and because of the wages they receive, do not carry out any ‘useful work’. Concerning the livestock, he once again pointed out the scarcity and poor quality of the livestock, with almost 50% of the transport wagons and livestock being unavailable due to illness or breakdown.

As mentioned above, the 1914 budget included a large budget item for the cleaning service (1 million pesetas from 1914 to 1917), which was used to increase the number of staff (55 workers, 34 foremen and 138 assistants). On the other hand, the cattle were gradually replaced by mechanical traction vehicles. However, the layout of the streets in Madrid and the limited development of carts made it difficult for them to move through narrow streets. On the other hand, due to the World War, the number of tools, spare parts and utensils used in the street cleaning service and the capacity to find spare parts on the market were reduced. This was skilfully replaced by the various engineers and service managers who devised different types of vehicles that were adapted to the needs and layout of the streets. About the work centres, a request was made to incorporate the premises located in Santa Engracia street (Parque Norte) into the cleaning service and construction began on the central park (in Plaza de la Cebada).

Taking advantage of this wave of reforms in the municipal service, the Madrid City Council published in 1917 a modification of the municipal regulations of the street cleaning service (Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 1917) which highlights the creation, classification and codification of the different professional categories both in the execution of the service and in administration. It establishes the obligation for all service personnel to wear a municipal uniform. It develops the obligations of each of the professional categories, incorporating a chapter exclusively dedicated to “faults and their correction” where they are divided into serious and minor faults. Art. 58 establishes for the first time the offences of not considering decorum and due correction, as well as the lack of uniformity or personal cleanliness. Drunkenness (often in the service) or abandonment of the service is also to be considered a serious offence. Finally, for the first time, a regulation was established for promotion in two ways, by seniority or by the election of the individual by his superiors based on merit.

The service was divided into 2 shifts, with guards available 24 hours a day. It is also noteworthy that the training of personnel was made compulsory, including at least 2 teachers on the staff to give basic level classes with compulsory attendance during working hours.

Following on from the above, and with the exception made in the statistics themselves, where it was reported in 1921 that in 1919 and 1920 the data collected on the total number of workers in Madrid was not sufficient due to deficiencies in the census system based on individual declarations, the labour statistics for Madrid for the years 1921 to 1928 are analysed. First, we can observe the high incidence of deaths due to diseases derived from the provision of cleaning services, with an incidence of up to 15% due to pulmonary tuberculosis. Also noteworthy is the constant growth in the number of workers in the cleaning service in Madrid, from 984 in 1908 to 1499 workers in 1928.

The cleaning service became increasingly important, not only because it was a service directly managed by the Madrid City Council, but also because of the responsibility to prevent the spread of diseases such as the typhus epidemic of 1885 (Pinto Crespo, 1998), as well as the attempt to adapt the city and its services to the strong demographic growth that was taking place. A Bando was published on 14 June 1921, mentioning the impossibility of keeping the city clean if the people of Madrid did not stop dirtying it. It insisted on raising public awareness of the need to keep the city clean and reiterated the prohibitions of previous bans. In other words, the aim was to change the habits of the citizens to make the service less costly for the municipality.

Finally, in 1925, a new modification of the cleaning service regulations was published, which included a much more extensive list of professional categories. It is interesting to note the incorporation of personnel such as barbers, veterinary nurses or sworn guards and the regulation of professions that were only mentioned in the previous regulations, such as teachers. It expressly stated that the mission was to eliminate illiteracy among the staff to try to instil in the workers a ‘love of culture’, detailing even how often each worker should cut their hair or shave (Madrid, 1925).

The modifications from this point onwards were oriented in the same direction as those described above until the outbreak of the civil war and the effects it had both on the cleaning sector and the whole city of Madrid.

6. The influence of the political transition on street cleaning: the foundations for future privatisation (1975 - 1980)

In the Spanish context, after Franco’s death on 20 November 1975 and the beginning of the transition, the 1978 Constitution in its Title VIII EC ,under the heading ‘the territorial organisation of the state’, dedicates its Chapter II to the local administration. In this way, Article 140 states that:

“The Constitution guarantees the autonomy of the municipalities. They shall enjoy full legal personality. Their government and administration is attributed to their respective Town Councils, made up of mayors and councillors. The councillors shall be elected by the residents of the municipality by means of suffrage (…)]”.

The immediate repercussion of this fact is that, taking into account the special circumstances of Madrid's capital status, local authorities gained a new momentum in autonomy and importance. From this point onwards, it is appropriate to analyse Madrid’s cleaning service bearing in mind the political changes at the municipal level, without forgetting the regional-national-international dynamics and interactions.

Following the information in the thesis of Cárdenas (2017) and the work of Catalán Vidal (1991) from 1974 onwards, a weakening of the Spanish developmental model of the previous stage could be observed, as the international crisis coincided with the internal economic crisis. (Marglin & Schor, 2000). The Moncloa Pacts signed in 1977 attempted to correct the monetary imbalances and, in 1978, inflation was brought under control; however, growth was highly volatile and unemployment increased. (Cárdenas del Rey, 2017). In March 1980 the Estatuto de los Trabajadores (Workers' Statute) was approved as the general framework for labour regulation and gave way to the elimination of restrictions on dismissal and the flexibilisation of the labour market. (Balbona, 2013).

The municipal context is also changing. Juan de Arespacochaga, elected Mayor of Madrid in 1976 for the Alianza Popular formation, still under Franco’s institutions, had the first meetings with the neighbourhood associations and developed improvement plans for the suburbs. This was very relevant for the street cleaning service, as the dynamics of opening up to private companies began. In 1978, José Luis Álvarez was appointed mayor of Madrid (by government designation), although he remained as mayor for a very short period of time, since in 1979 the first democratic elections were held and the sum of votes obtained by the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) enabled the election of a mayor.

At this stage, there was growing tension in labour relations due to the lack of a sufficient budget for the street cleaning service. On the other hand, in many of the southern districts that were incorporated in the 1950s, there was no ‘complete’ cleaning service; instead, cleaning was carried out on an ad hoc basis, partly due to the lack of a sufficient budget to renew and expand both the staff and the machinery. At the end of 1976, the creation of special brigades was approved to carry out cleaning activities which, like those included in the ordinance, were incorporated as obligations of the street cleaning service during 1977 (such as cleaning bus lanes, maintenance of plots of land and level crossings). However, it highlights the need for the cleaning brigades to be assigned to the districts mentioned above (no brigade is assigned to any district within the M-30 ring road)4. Finally, bargaining power and union power are being limited through the ‘diversification of services’ formula and this starts in the southern areas of Madrid (García, 1981). However, the trade union centres in the street cleaning sector continued to have a great capacity for mobilisation and in 1978, after several strikes, it was approved that the staff should have a day and a half off for relief work (half of the staff worked in rotating shifts on Saturdays and the whole staff was free on Sundays). (Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 1984). Over time, this fact forced the creation of a specific shift for weekends and public holidays.

In 1978 the budget was frozen and no rolling stock was purchased and no vacancies were filled for the 3,000 operating personnel for all the districts of Madrid. (Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 1980). Therefore, if we have to point out a date when private companies started to take over the execution of the service in some districts of Madrid, it would be the year 1977 (Arnanz, Díez, & Fernández, 2000) with districts such as Villaverde, Vallecas, Latina or Carabanchel in 1978, a trend that increased in later stages, as we shall see, until the complete privatisation of the service.

In conclusion, during this period, Madrid found itself in a context of international and national crisis. The old Francoist structures, headed by the last non-democratic mayor, began to privatise the street cleaning service. Under cover of the need to provide the new districts of Madrid with this service, they created specific brigades managed privately and which carried out specific actions (outside the activities regulated by the municipal street cleaning service) but which were later included as part of the service’s activities. This limited the capacity for trade union action, as the new brigades did not belong to the cleaning branch of the Madrid City Council and, therefore, to be able to carry out adequate trade union activity, they first had to be consolidated in these new companies. On the other hand, over the course of these years, the unions aimed to improve very precarious working conditions in the street cleaning sector of the Madrid City Council. After many conflicts, the possibility of a fixed rest day and a half a week was achieved. This fact meant de facto the need to increase the workforce to create a new shift and was used, along with the economic crisis, as an explanation for freezing the budgets in 1978, which meant, as we will see later, strangulation of the service in three ways: limitation of trade union activity, budget and human resources.

7. Privatisation planning and project implementation facilitating future privatisation (1980 - 1990)

In Spain, the 1980s were a period of expansion followed by a period of recession in 1992-1993. (Cárdenas del Rey, 2017). Internationally, economic structures gradually became increasingly internationalised and financialised. (Alvarez, Luengo, & Uxo, 2014). The state encouraged the loss of trade union bargaining power and gave priority to monetary stability, market liberalisation and external openness. On the other hand, it was confronted with the fulfilment of the commitments acquired with the entry into the European Union. The most relevant for this article was ‘The Medium-Term Economic Programme’ (1983-1986) with the liberalising content of the economy, as well as massive privatisations of public enterprises. (Cárdenas del Rey, 2017). The concentration of capital increased both through the concentration of profits and through mergers and takeovers, such as the companies ACS, OHL, Ferrovial, Sacyr, etc. (multiservice companies that carry out urban sanitation in the country's main cities). These companies would be of relevance in the coming decades as they gained access to public cleaning contracts in Madrid. Large national companies were beginning to compete on an international level (including public service contracts). How business groups are configured in Spain is closely related to how the privatisation of public companies and services took place. (Vergés, 2013-2014).

In Madrid, on 3 April 1979, elections were held in all Spanish municipalities. No list obtained a sufficient majority. Finally, the PCE with its 9 councillors agreed to make Enrique Tierno Galván (PSOE) mayor. On 8 May 1983, the second democratic elections were held in Madrid. Enrique Tierno Galván was re-elected mayor of Madrid. However, he died during the term of office. In 1989, Alianza Popular (Popular Alliance) proposed a motion of censure, and Rodríguez Sahagún (CDS, formerly UCD) was sworn in as mayor on 29 June 1989 until new elections in 1991.

During this period, an attempt was made to modify the cleaning by-laws, although relatively new by-laws were still in force. At the same time, an attempt was made to manage the structure of relations with agents inherited from the previous regime, where on the one hand we had a workforce with great trade union mobility and with strongly rooted and institutionalised trade unions in a general context of degradation of trade union capacity, but on the other hand companies were created which, either through relations with the previous system or through takeovers or mergers, led to the rapid constitution of service companies that could carry out the street cleaning service in the capital.

During these years, there was a continuous increase in tensions between workers of private companies, workers of the Madrid City Council, the public administration itself and private companies.

The new government team, which stood for election with an electoral programme that included the municipalisation of public services as one of its main lines of action, highlights the following as the main problems of the cleaning service (Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 1980) personnel management, which took place within a framework of public administration relations (control of salaries, scales, timetables, absenteeism, etc.). Also problematic was the lack of mobile material due to the freezing of the budget during the previous legislature, as well as the lack of agility in obtaining spare parts and new tools.

However, in an interview with Emilio García Horcajo, Councillor of Personnel, Internal Regime and Administrative Reform (PSOE) (Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 1982), he mentioned the reasons for continuing the privatisation of the cleaning service in the capital, including the southern districts managed by private companies and also the northern districts. On the one hand, there was no personnel policy for several years in the cleaning service of Madrid and therefore the staff was old and insufficient. On the other hand, there was a structure inherited from previous legislatures where municipal workers and workers from private companies coexisted within Madrid, under the slogan of ‘diversification’. Finally, risks of possible conflicts had to be eliminated, as the service was ‘diversified’ into different companies and with different actors involved. It was difficult for workers to reach an agreement and union power was reduced, but not so much business power in the management of the service since the companies that provide these services were very few and are under the umbrella of a single employer.

The existence of private companies carrying out the service in the southern districts (outside the M-30) Latina, Villaverde, Carabanchel and Vallecas lead to the division into 2 types of workers doing the same job. The workers of the private companies had to start negotiating the collective agreement as they were not regulated by statutes, unlike the case of civil servants of the Madrid City Council. This provoked a wave of strikes for better salaries, social benefits, working hours etc. However, despite the differences, there was a high level of trade union activity with responses of solidarity from both contract workers and Madrid City Council workers. In 1980, a 12-day strike of the 700 cleaning service workers in the districts managed by private companies began5. This was a tool used with a double purpose, with companies willing to put pressure on the public administration and workers intent on negotiating improvements in their work. On 7 February 1984, new mobilisations were called again, including strikes6. There were also new stoppages in March 1988 and May 1990, in which both the Labour and Social Security Inspectorate and the City Council itself intervened. In these last strikes, 7 districts were involved, as those in the north were also included among those managed by private companies.

During this stage, a dual model persisted where, on the one hand, there was an attempt to reduce union power and, on the other hand, an improvement in the municipal service through substantial increases in the budget to be dedicated to the expansion of the machinery, the improvement of the cleaning of facades and the creation of 500 jobs in the privately managed districts. The latter was presented as an achievement of privatisation, “the creation of more than 500 jobs in the cleaning service (...) thanks to specialised companies that allowed the concentration of municipal resources in the central districts” (Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 1983).

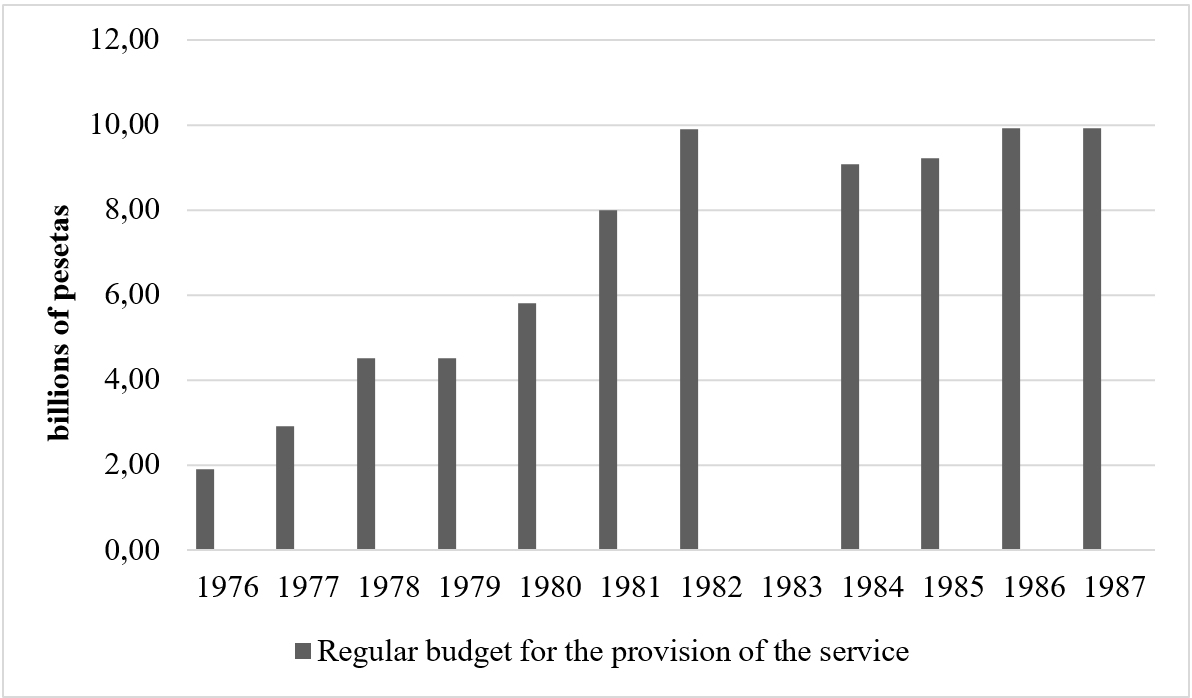

Finally, we can see in the chart below (Figure 1) how the budget dedicated to street cleaning was completely insufficient in the previous stage (the 1970s), accounting for barely 20% of the funds that would be dedicated later on. It was not until 1981 that there was a notable change in the budget dedicated to street cleaning, which remained constant in the following years.

Source: Prepared by the authors, data from the Madrid street cleaning section, Environment, Madrid City Council.

Figure 1 Annual budget for the cleaning department - Madrid City Council

It has not been possible to have access to the 1983 budget for street cleaning (within the Department of the Environment) as the data that has been preserved only reflects the preventive municipal budgets in income and expenditure (Municipal Statistical Yearbook of 1983) without a breakdown of the items. Although there are publications from the previous days that reflect the negotiation of the budgets in which budget increases of 5% were spoken of, it is risky to consider this figure to be real. In 1984, Madrid’s population continued to grow and reached 3,188,297 inhabitants7. One of the first analysis documents was approved which, as was the case in previous stages, was not a mere project proposal, but a real plan for cleaning up Madrid.

In the analysis of this Cleaning Plan for the city of Madrid, we find the division that had already been proposed in previous stages between street cleaning, waste collection, waste treatment and special actions. On the other hand, the first thing that is striking is the very clear plan following the trend towards privatisation of the service, based on the ageing of the workforce and the lack of gradual investment in the service. The plan of action was as follows:

“The final goal, which should be prepared from now on, is to reach 1997 in such a way that in that year the whole of Madrid, divided into 18 districts, can be put out to public tender. The tender in each of them will include both street collection and street cleaning, as well as a large part of the special services that can undoubtedly be included in the contracts” (Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 1984).

The action plan for the first four-year period was to contract the service to specialised companies (Madrid City Council, 1984)8. The lines of action for the second four-year period, 1988-1991, aimed to increase the number of street cleaning contracts and to extend others already in force so that their characteristics could be homogenised in the future.

“The municipal action in this respect will be as follows: contracting street cleaning services between 1989 and 1990 in the following municipal districts: Retiro, Salamanca, Centro and Chamberí. Extension of the street cleaning service contracts in the municipal districts of Latina, Carabanchel and Moratalaz” (Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 1984).

In 1981, 180 workers were hired to work a new shift at weekends and on public holidays (although initially they only covered the daily staff's breaks, i.e. half of Saturday and the whole of Sunday). The staffing per district in 1984, according to the hired company and the year of the beginning of the contract, is depicted in table 1 (Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 1984):

Table 1 Workers, contracts and companies by districts private management and public management (1984)

| DISTRICTS | NO. OF WORKERS (ALL CATEGORIES AND SHIFTS) | START OF THE CONTRACT | CONTRACTED COMPANY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carabanchel and Latina | 297 | 13/02/1978 | ALFONSO BENITEZ S.A. |

| Villaverde and Mediodía (Manzanares riverside) | 196 | 01/08/1977 | CONSTRUCCIONES Y CONTRATAS S.A. |

| Vallecas and Mediodía (Manzanares riverside) | 194 | 01/08/1977 | CESPA S.A. |

| Fuencarral | 138 | 30/12/1981 | NO DATA AVAILABLE |

| San Blas | 140 | 30/12/1981 | NO DATA AVAILABLE |

| Hortaleza | 119 | 30/12/1981 | NO DATA AVAILABLE |

| Moratalaz | 95 | 30/12/1981 | NO DATA AVAILABLE |

| Madrid City Council (9 districts) | 2037 | - | - |

| TOTAL | 3216 | - | - |

Source: Own data from the Madrid city cleaning plan and white book on cleaning in Madrid, Medio Ambiente, Madrid City Council.

In summary, during the period from 1980 to 1990: a) the first large multiservice companies were created and began to take over the first street cleaning contracts for the areas of Madrid that were not part of the municipal service; b) in 1983 the Madrid City Cleaning Plan was approved, which set a deadline of 1997 for all the districts of the city to pass to private management; c) although the municipal government team, at the beginning of the 1980s, stood for election and one of its main political axes was the municipalisation of public services, disaffection with the street cleaning service quickly began to be expressed, the main reasons being the difficulty created, in terms of human resources, by the fact that the service staff was regulated by public statutes, the ageing of the staff due to the lack of investment during the previous period, as well as the lack of agility in the service to solve fixed capital problems due to the long process of public budgets; d) the municipal government proposed to continue with the private management of street cleaning in the southern districts, which had already begun in the previous stage (1970-1980) and, in addition, to add the northern districts to private management where the municipal workforces were elder to move these municipal workers and to be able to concentrate them in fewer and fewer districts; e) there was budgetary stagnation in the street cleaning service. The small increases chieved during this decade were aimed at improving service management contracts with private companies, so that the number of staff in the privately managed districts increased while the municipal workforce was increasingly reduced; and f) there was a strong trade union presence in the workforce, with a great capacity for mobilisation inherited from previous stages, which had to face the division of the service between areas with staff regulated by public statutes and areas with staff that would have to start negotiating collective agreements from scratch and, together with this division of objectives of the workforce, there was a general attempt in Spain to weaken the trade unions as a result of the reforms of the labour framework. This was a decade of strong labour conflict in the city’s cleaning service, with indefinite strikes in 1980, 1984, 1988 and 1990.

8. Consolidation of the model and start of the privatised service (1990 - 2000)

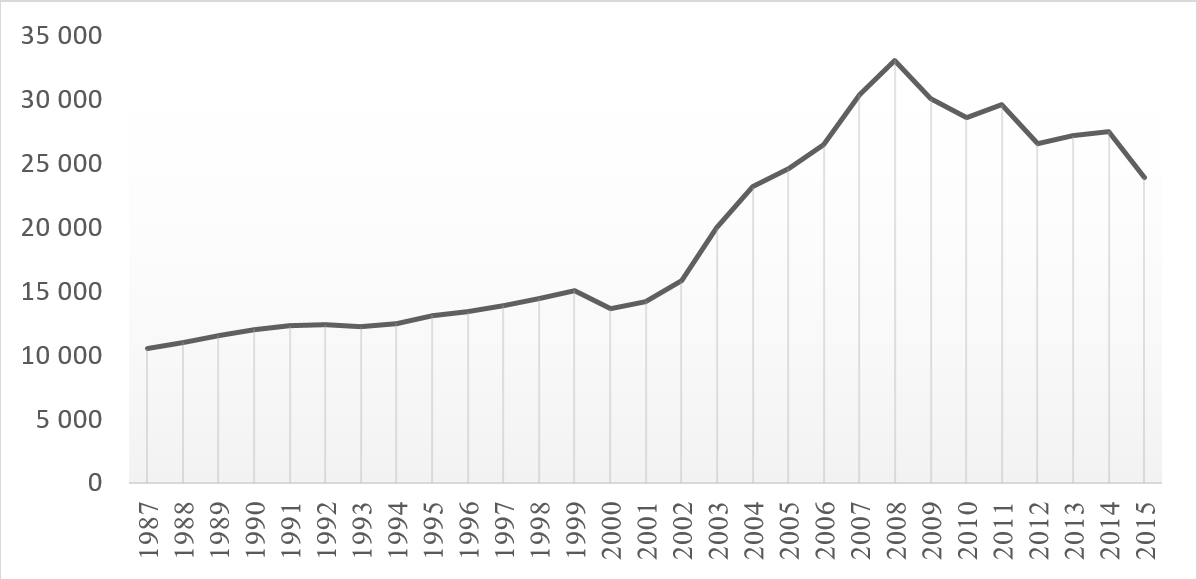

In Spain, economic growth from the 1990s onwards corresponded to a period of expansion from 1994 to 2008, a recession at the turn of the millennium and a slowdown from 1992 to 1994, as can be seen in the following chart of GDP per inhabitant. At the end of the 1990s, a process of strong expansion began in which two elements stood out: on the one hand, a constant increase in GDP and significant growth rates, driven by the real estate sector, and on the other hand, a reduction in interest rates as a result of the ECB's expansionary policy. (Bellod Redondo, 2007).

Source: Own elaboration with Maddison-project data and average change 2010-2016 with World Bank data.

Figure 2 Spain's GDP per capita

In Madrid, municipal elections were held in May 1991 and the Partido Popular (AP's new electoral brand) won the Madrid City Council, and José María Álvarez del Manzano was sworn in as Mayor of Madrid. The PP would renew its absolute majority in the 1995 and 1999 elections. In the elections of June 2003, Alberto Ruiz Gallardón took over the baton for the PP, who in 2011 became Minister of Justice, with Ana María Botella Serrano taking over the mayoralty as number two on the PP list for the mayoralty of Madrid.

During these years, the cleaning plan for the city of Madrid (approved in the previous period of 1980-1990) was implemented, but there was an acceleration in the process that led to the privatisation of most services by the mid-1990s. Additionally, the Madrid City Council sustained the creation of a body to control both the actions of the companies and to evaluate the work carried out. Thus, in 1992, the body of environmental agents was created with 124 agents, which was expanded until the present day9. On 7 September 1992, Luis Molina, head of the Madrid City Council's cleaning department, declared his intention to “put pressure on the companies”10 to ensure that they complied with the contracts, as the companies had failed to comply with them. For their part, companies stated that the Madrid City Council had not paid them for more than 6 months.

The behaviour of the cleaning contracts began to reveal deviations from the signed contracts and a survey published on 4 March 199211 mentioned that 83% of the inhabitants in the central district believed that Madrid was dirty. In the meantime, the capital continued to obtain year after year the award of the English foundation TidyBritainGroup which declared Madrid to be the dirtiest European capital in 1992, 1993 and 199412. In an interview with Rafael López (General Secretary of various activities of the most representative trade union CCOO), he mentioned that the contractually agreed cleaning campaigns were not being carried out, that workers were not being replaced and that there was a lack of renewal of mechanical means13.

Conflicts over the relationship between contractors, workers and the public administration continued and after a strike lasting more than 23 days, the government intervened to submit the negotiations to arbitration14. However, as mentioned above, as municipal and contract workers coexisted in different districts and even within the same district, there was a difference in labour rights and wages. (Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 1984). This led to a strike lasting more than 11 days, in which the employers refused to equalise labour and wage rights with respect to the municipal workforce15. Finally, Mayor Álvarez del Manzano intervened in the negotiations and after another 13 days of strike, the possibility of equalising wage and rest day conditions between municipal and private contract workers was formulated in the medium16. Finally, after more than a month of strike action, arbitration was required to resolve the conflict.17

In 1994, the municipal technicians responsible for the most sensitive areas within the Department of Environment (waste and cleaning) expressed their alarm and disagreement with the tendering procedure chosen for the contracting of 15 districts of Madrid18. This was carried out exclusively based on the lowest bid and finally, the service was contracted for a period of 8 years as follows:

Table 2 Contracting street cleaning 15 districts 1994

| DISTRICT | CONCESSIONARY COMPANY |

|---|---|

| Latina (Zone 6) | TECMED (Urbaser) |

| Carabanchel (Zone 6) | TECMED (Urbaser) |

| Centre (Zone 8) | TECMED (Urbaser) |

| Argüelles (Zone 8) | TECMED (Urbaser) |

| Moratalaz (Zone 3) | TECMED (Urbaser) |

| Vicálvaro (Zone 3) | TECMED (Urbaser) |

| Usera (Zone 5) | Alfonso Benítez (FCC) |

| Villaverde (Zone 5) | Alfonso Benítez (FCC) |

| Fuencarral (Zone 7) | Alfonso Benítez (FCC) |

| Tetuán (Zone 7) | Alfonso Benítez (FCC) |

| Hortaleza (Zone 1) | Alfonso Benítez (FCC) |

| Barajas (Zone 1) | Alfonso Benítez (FCC) |

| Chamartín (Zone 2) | Cespa (Ferrovial) |

| San Blas (Zone 2) | Cespa (Ferrovial) |

| Villa de Vallecas (Zone 4) | Cespa (Ferrovial) |

| Puente de Vallecas (Zone 4) | Cespa (Ferrovial) |

Source: Prepared by the authors with data from Madrid City Council, urban cleaning area.

The districts of Madrid were zoned and distributed to very few companies. In these new street cleaning contracts, it was clear that the councillor for the environment, Esperanza Aguirre, intended, from 1994 onwards, to create a contract for private companies to carry out control of the performance of the concessionary companies using quality indicators.19 In addition, she stated her intention to complete the privatisation of all the districts of Madrid. In this sense, Luis Molina, a councillor of the Madrid City Council for the PP in 1994 (Arnanz, Díez, & Fernández, 2000) stated that the reasons for the complete privatisation of Madrid lay, above all, in the fact that the cost of cleaning was cheaper due to the greater agility of the private company. The time off and social benefits of civil servants meant that more people were needed to do the same work, and there were rigidities in the possibility of modifying working conditions that did not exist to the same extent in private companies.

In the 1998 survey of both municipal and private contract workers on their working conditions, workers’ perception of private service provision was not very positive (Arnanz, Díez, & Fernández, 2000). In particular, 74% of the workers interviewed considered that public-private integration in some districts seriously undermined service delivery, and 85% considered the conditions under which the service was provided to be poor or fair. 20% of the workers stated that the service provided by private companies was not very positive. 20% of the workers said that they had sometimes have to buy their work clothes such as boots or gloves; almost all said that there were very old districts such as Salamanca, Chamberí or Moncloa where the average age of the cleaning workers was 60 years. However, union representation was perceived as positive for the workers (61.66% said it was good and 12% bad).

In line with the above, the following chart shows, with real data, the reduction in the number of workers by the street cleaning concessionary companies (on the one hand, to save costs and, on the other hand, due to the increase in mechanisation). If we look at the data on the number of workers in 1992 and 1993, the following stand out: a) the number of municipal workers did not significantly grow in terms to the number of municipal workers that existed seventy years before as the increase in these municipal workers had been absorbed via private contract workforces. b) a drop in the total number of workers and, above all, municipal workers, with a 46% reduction of employees between 1990 and 2000.

This situation, however, changed with the beginning of the new century since, due to the expansive economic situation, not only the population of Madrid and the surface area of public roads grew, but also consumption and, consequently, waste generation. In addition, tourism20 and construction sector activities increased considerably from the end of the 1990s onwards21. All of this influenced the increase in the street cleaning budget, which in turn was directed towards improving contractors’ compensation.

An increase in corruption22 was highlighted by the fact that, following the open trial of the Gürtel plot, the former councillor for the Environment of the Madrid City Council was tried for fraudulent use of public auctions. However, in the judge’s order it is possible to observe the existence of a way of operating that was not alien to any of the agents involved in the operation. The auctions included a weighting that facilitated the awarding of public street cleaning contracts to certain companies. Additionally, the specifications established activities that the contractors were not going to carry out but that the City Council would pay for as if they were being carried out. All of the above was done through the collection of various commissions, leading to the opening of various legal proceedings that ended with final sentences against the concessionaires who had paid the commissions (Gürtel Madrid Época I: 1999-2005).

In summary, during the period of 1990 to 2000: a) the national situation is one of moderate economic growth that would end in a great economic expansion in the decade of the 2000s; b) the cleaning plan for the city of Madrid, approved in the 1980-1990 period, planned to end with the privatisation of all the districts of Madrid in 1997. The change of government in Madrid accelerated the process and in 1995 the privatisation of the service was completed; c) there was widespread dissatisfaction with the performance of the service concessionaires who, as their presence in Madrid increased, were increasingly in breach of contract. For their part, the contractors reported constant non-payments by the Madrid City Council. All this led to Madrid being named the dirtiest European capital for three years in a row (1992-1994); d) the staff expressed a great rejection of the situation that was being experienced and the majority observed a high level of degradation of the material and working conditions in which the service was being carried out. There was a strong trade union response which led to indefinite strikes from 1991 to 1995 to equalise the working conditions of the municipal and private contract staff and to try to stop and, in any case, improve the conditions under which privatisation was taking place. During these years, the municipal government, and the mayor himself had to intervene and even two arbitrations had to be held to try to put an end to the strikes; e) in 1995, the public contracting of the private execution of the street cleaning service in the rest of the districts of Madrid was put out to tender. The most important factor when awarding the tender was the economic proposal offered by the companies. The performance of the street cleaning service in Madrid was divided among three companies (Fomento de Construcciones y Contratas, Urbaser and Ferrovial); f) the difference between the number of municipal workers at the beginning of the decade (1992) and at the end (1998) decreased 46%. In addition, there was a reduction of 34% in the total number of workers; g) at the end of the stage, there was an improvement in macroeconomic conditions that projected additional expansion during the 2000s. This was taken advantage of to economically improve the street cleaning contracts which, in turn, generated various cases of corruption in the public contracting of the service.

9. Conclusions

In response to the first hypothesis, the study shows that the first decision to create a privately managed cleaning service parallel to the existing municipal cleaning service was taken by Mayor Juan de Arespacochaga y de Felipe in 1977 and 1978. This decision was taken with a twofold intention, on the one hand to solve the lack of a cleaning service in some districts of the city and, on the other hand, to ‘diversify’ the capacity for trade union action by creating two workforces with different labour regulations and working conditions. Subsequently, in 1984, after various labour tensions and conflicts, gradual privatisation of the service was planned, with a deadline of 1997. This planning was the municipal government’s response to the existing duality of the workforce, the lack of investment in human and material resources due to budgetary limitations during the previous stage and the difficulty in its management as a consequence of public regulation (via budgets or statutory labour regulation of human resources). Finally, after 1989 and the entry into the government of Mayor Jose María Álvarez del Manzano, privatisation accelerated and was completed in 1995, which led to an intensification of trade union conflict and a deterioration in the quality of the service and the working conditions of the workers.

Although in the first stage it stood out that there were personnel from private companies contracted to carry out specific cleaning actions that would later cover more districts of Madrid, in this case, the service is not considered to be privatised as the municipal service continued to operate as it had done in previous decades. There were two periods: a first one in which the measures adopted were aimed at overcoming a temporary phase, trying to eliminate the problems pointed out by the institutions (the difficulty in human resource management), all lacking planning for the future of the service; and a second period in which these elements, in turn, caused the deterioration of labour relations and the quality of the service, which this time led to the creation of a plan for the privatisation of the service. The main actors at no time expressed problems with the quality of the municipal service, but rather problems in its management, so privatisation was a way of ‘externalising’ the management and responsibilities of the public service. The idea of cost reduction and improved service quality of private vs. public management emerged as an explanation for privatisation in the period of 1990-2000. As indicated above, although there were plans for the privatisation of the service and deployment of companies during the 1970s and 1980s gradually preparing the ground - from a political, social and labour perspective - for privatisation to proceed, privatisation (understood as a municipal service going private) did not begin until the 1990s.

Assuming that the first hypothesis is correct and that, to a certain extent, the privatisation of the service was planned, the first sub-hypothesis is confirmed, since there was a triple limitation of the service (trade union activity, budget and human resources) during the 1975-1980 period, the consequences of which (ageing and duality of the workforce, trade union conflicts, ageing of material resources and difficulties in budget management) were used as justification for the planning of privatisation during the 1980-1990 period. Similarly, the second sub-hypothesis is also confirmed, since in the first stage (1975-1980) the measures were adopted by a Francoist government, and in the second stage (1980-1990) measures were adopted by a PSOE (PCE) government and, finally, in 1990-2000 by a PP government. The difference lies in the intensity of the measures and the time taken to implement them, with more extensive privatisation measures and less time taken to implement them during the first and third stages compared to the second stage.

Finally, the second hypothesis is also confirmed but should be limited in time. There was a clear worsening of working conditions experienced by privately managed workforces since the first contracts in 1977. Trade unions had to establish themselves in the new workforces and initiate the negotiation of a new collective bargaining agreement and, therefore, an important part of the workers’ demands during the three stages was aimed at trying to equalise the working conditions of the privately contracted workforces with their municipal counterparts. Finally, once the cleaning service was privatised in all the districts of Madrid and, along with the improvement of the budget allocations for this service, the direction of the workers’ demands was directed towards the creation of a new framework of relations, with the working conditions of the already non-existent municipal staff being forgotten.