Introduction

In recent years, CSs have grown in popularity, with their number rising significantly in the last decade. CSs were born in the early 2000s with the idea of accommodating primarily workers falling out of standard employment (such as freelancers and solo entrepreneurs) allowing them to work and collaborate with each other’s. Nowadays, these spaces offer a more flexible and chilled-out alternative to traditional office spaces for remote workers, a potentially cheaper alternative to private offices for independent professionals and a valid alternative to homes for both. While there are undeniable benefits to working from home, such as saving time on commuting and enhancing workers’ autonomy, this practice can also have adverse effects on workers' wellbeing. The lack of ergonomic equipment which is typically present in an office environment can hinder homeworkers’ wellbeing, together with a possible increase in work intensity and a higher risk of social and professional isolation (EU-OSHA, 2021; Eurofound, 2020). With the rise of remote work in the last years (Eurofound & International Labour Office, 2017), CSs seem to be here to stay and possibly to further expand in the near future also beyond highly urbanised locations (Bosworth et al., 2023; Gandini & Cossu, 2021; Tomaz et al., 2022).

Nonetheless, research into how CSs may influence workers' wellbeing remains limited. This paper aims to fill this gap by conducting a systematic review of academic literature. By carrying out a thematic analysis of the selected papers based on the dimensions of QWL (Walton, 1973), several elements of CSs contributing to workers’ wellbeing will be identified. After defining the concept of wellbeing at work and QWL, their applicability to the contemporary work context and to work carried out in CSs, details on the methodology adopted will be provided. The paper will then discuss the results of the literature review, highlighting how CSs can improve or hinder workers' wellbeing and several aspects of the quality of their working life. In the conclusive section, the paper will summarise key findings, identify research gaps and offer suggestions for future research on this topic. By shedding light on the potential benefits and drawbacks of CSs, this paper seeks to contribute to the growing body of literature on CSs and the ways they affects working lives. The findings of this review may not only provide valuable insights for researchers but also inform policymakers and practitioners on the design and implementation of CSs that enhance workers' QWL and, ultimately, their wellbeing.

Workers’ wellbeing and quality of working life

According to the World Health Organisation (2021), wellbeing is “a positive state experienced by individuals and societies […], it is a resource for daily life and is determined by social, economic and environmental conditions” (p. 10). Wellbeing can refer to different units of analysis, such as the individual and the collective (Atkinson et al., 2020), and can be studied in its objective and subjective forms. While the first corresponds grossly to the concept of health, the second refers more specifically to the feelings and perceptions of an individual. Subjective wellbeing is usually operationalised into satisfaction and has been classically framed as hedonic or eudemonic, with the hedonic version being closer to a short-term enjoyment, and the eudemonic version being conceived as a long-term goal and a search for meaning (Ryan & Deci, 2001).

Workplace wellbeing is defined as a comprehensive concept, encompassing subjective aspects such as employee satisfaction and engagement, as well as objective aspects such as their safety and health (Schulte & Vainio, 2010). Several frameworks of analysis have been developed to identify possible positive and negative inputs to workers’ wellbeing. One of the most widely used in the field of organisational psychology is the job demand and control model developed by Karasek (1979), which links the level of mental strain with the interaction between external demands at work and job decision latitude, that is how much control and decisional power workers have over their work. In the years, there have been further elaborations of the model, including the job-demand-control-support model (Johnson & Hall, 1988), focusing on the positive role of social support at work in alleviating mental strain, and the job demands and resources model (Demerouti et al., 2001) that takes into account the buffering role of psychosocial, physical and organisational aspects acting as resources in relation to job demands.

In the field of organisational studies and sociology of work, a comprehensive framework encompassing the several resources and demands in the work sphere acting as possible aspects contributing to workers’ wellbeing is the concept of quality of working life (QWL). QWL refers to the aspects of work life which contribute to enhance or hinder workers’ wellbeing and was born as movement with the aim of contributing to workers’ quality of life and emancipation (Grote & Guest, 2017). In 1973, Walton outlined eight attributes defining QWL, which include 1) fair and sufficient payment, 2) safe and healthy work environment, 3) chances to use and enhance one's skills and abilities, 4) possibilities for continuous growth and stability, 5) integration into the work community, 6) constitutionalism in the workplace, that is the protection of workers’ rights, 7) work-life balance, and 8) the social significance of work, namely the engagement of organisations in socially responsible practices making workers pride of the work they do. Rather than being separated dimensions, these elements are indeed highly interdependent, at least in the context of CSs, as the results of this review will show.

Post-Fordist work and Quality of Working Life

The world of work has changed a lot since Walton’s theorisation of QWL, following the rise of non-standard employment forms and the flexibilisation and precarisation of a large proportion of work (Sennett, 1998). The 2008 financial crisis has further brought to a rise in contingent work, with the result of workers becoming increasingly precarious and with limited access to social protection measures (Standing, 2014). Moreover, the introduction of light-weight ICTs in the workplace has increased the risk of workers feeling constantly connected, blurring the separation of work and private life (Orlikowski, 2007). The emergence of passionate work (Arvidsson et al., 2010) has further complicated the distinction between work and leisure, with work pervading individuals’ time and space (Huws, 2016; Lewis, 2003; Webster & Randle, 2016). In terms of time, workers often experience long working hours and high time pressure due to tight deadlines. In terms of space, the potentially high mobility of workers, besides posing risks for their health and wellbeing, due to the lack of ergonomic equipment (Vartiainen & Hyrkkänen, 2010), may also bring about lower degrees of social support from peers and colleagues (Koroma et al., 2014).

In view of the rise of non-standard employment, Warhurst & Knox (2022) highlighted the importance of considering more consistently employment forms when studying QWL given their possible influence on workers’ wellbeing. Indeed, job precarity has a negative effect on workers' wellbeing, with job intermittence and income insecurity linked to adverse effects on both physical and mental health, including anxiety and burnout (De Witte et al., 2016; László et al., 2010). Considering the QWL framework originally identified by Walton in the light of newer employment forms, such as freelancing and solo self-employment, it emerges that, if on the one hand, these workers tend to have higher levels of autonomy in handling tasks, and thus an increased possibility to apply and enhance their skills, on the other, they lack the support of unions guaranteeing their rights, are left alone to deal with non-payment, and do not have access to social protection measures, such as parental and sick leave. Moreover, independent workers can adopt their own work culture, without being bounded to an organisation, and are potentially more in a position of perceiving their work as meaningful and in line with their values. In fact, freelancers, especially in early-career stages, may find it difficult to refuse jobs even if they do not find them meaningful, may deal with prolonged periods of non-work and precarity, and may need to engage in unpaid labour in the hope to get better jobs in the future.

Perhaps the most important aspect to mention is that if QWL was born as a guideline for employers to enhance workers’ wellbeing and improve workplaces, independent workers nowadays are left alone with the burden to provide for their own wellbeing and quality of life at work (see also Sointu’s study (2005) on how wellbeing at work is increasingly perceived as an individual responsibility). It could be argued that CSs emerged as a possible way of independent workers to provide for themselves, coming together to benefit from a quasi-organisation that could give more structure to their work day and provide them with some traditional office-like benefits. Although independent professionals still seem to make up the majority of CS users (Arvidsson & Colleoni, 2018; Avdikos & Kalogeresis, 2017; Pacchi & Mariotti, 2021), CSs may play a similar role also for remote employees.

Coworking Spaces and Quality of Working Life

According to de Peuter et al. (2017), “coworking spaces constitute infrastructure that makes flexible labour regimes more robust” (p. 5) and which allow workers to benefit from “the same support structures that you would have if you were part of a wider organization…” (p. 14). Building on this, CSs could be considered as quasi-organisations providing a physical, social and technological infrastructure to self-employed and remote workers. As any other workplace, CSs may be considered in sociomaterial terms (Aslam et al., 2021; Orlikowski, 2007). Following Aslam et al.'s (2021) approach which looked at the role that CSs, in their sociomaterial elements, may play in entrepreneurial processes, this paper reviews the available literature looking at how the sociomateriality of CSs may affect workers’ QWL, ultimately contributing to their wellbeing. According to Aslam et al., in the available literature, physical and spatial components of CSs are often overlooked in favour of immaterial social aspects, while the phenomena researchers observe in these spaces, such as collaboration and innovation, are the result of the interweaving of social and material elements. A similar line of argument can be easily applied when considering the production of workers’ wellbeing in CSs. A sociomaterial perspective allows to consider the complex interplay between the material and social aspects of CSs and their contribution to workers’ wellbeing. Promoting wellbeing in CSs, as in any other workplace, calls for a holistic approach considering workplaces in the interrelation of their physical, technological, and social elements.

Unlike office-based employees, CS users are involved in multiple work environments. This is particularly noteworthy for remote workers as the coworking spaces they utilise are not owned or directly managed by their employers. This creates a dual influence, as remote workers are affected not only by the remote management that shapes their job design, task nature, work teams, work culture, and integration into virtual work communities, but also by the CSs in which they work, which exert similar effects. Independent workers experience a similar situation, as their job design and opportunities to apply and enhance their skills depend on clients, work teams, and their use of online platforms. Consequently, aspects of workers' jobs that are beyond the control of CSs play also a significant role in determining workers' wellbeing. Therefore, it is essential to acknowledge this multi-presence of workers in various virtual and physical workspaces (Koroma & Vartiainen, 2018) when considering the diverse factors and domains that contribute to workers' wellbeing. Nonetheless, this review, will focus exclusively on examining the role played by CSs in relation to workers' QWL and overall wellbeing.

Methodology

This paper presents a review of the available literature to understand which elements of CSs may affect workers’ QWL and, ultimately, their wellbeing. A similar approach was adopted by Vogl & Akhavan (2022) to study collaborative workspaces in peripheral and rural areas. In April 2022, I conducted a first literature review with an exploratory purpose to understand if and how CSs were affecting workers’ wellbeing. This work was presented at the TWR conference held in Milan in September 2022. This first review evidenced that CSs could affect workers’ wellbeing indirectly by acting upon several dimension of their work life. The QWL schema was thus considered to grasp this indirect role of CSs for workers’ wellbeing. The present literature review adopts to a large extent the PRISMA protocol (Page et al., 2021) and is based on the following research question:

How do CSs contribute to members’ QWL and wellbeing?

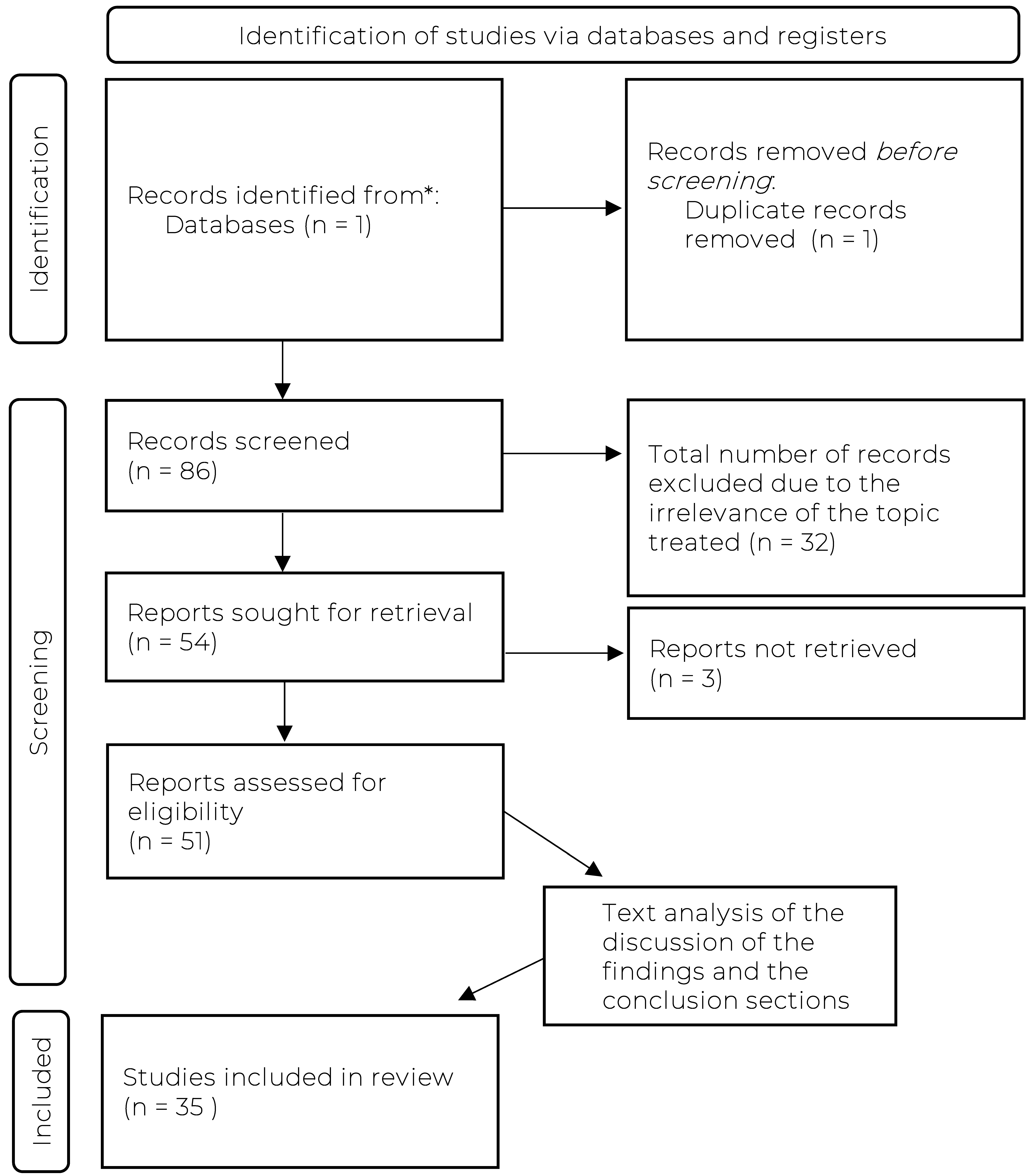

Due to time constraints and the presence of a sole reviewer to conduct this study, only one database was consulted. Scopus was chosen given its larger coverage of journals in the social sciences compared to other databases such as Web of Science (Mongeon & Paul-Hus, 2016). The words and expressions searched had to be included in the title, abstract or keywords of the database items. Considering the paper’s objective, the search terms included, besides coworking space, words as wellbeing, quality of work life, and several expressions reflecting the QWL dimensions identified by Walton. The formula utilised for the keyword search and the PRISMA flow diagram are included in the Appendix. The search was conducted in the first months of 2023. Including criteria were that 1) the publication had to be an article; 2) the source type had to be a journal; 3) the language of the publication had to be English. The search included also articles in press.

The search resulted in 86 unique articles. Results were exported from Scopus in a .csv file and converted into an .xlsl format. Articles were then checked for two main elements: 1) abstract and title should have been in line with the topic of the review, and able to answer the above-mentioned research question at least partly; 2) articles had to be based on empirical research. Only articles researching specifically CSs were included in the review, while studies analysing similar workplaces, such as fablabs and makerspaces, or that analyse coworking as practice rather than as space, were excluded. Following this check, 32 items were excluded given the irrelevance of their abstract and title, or because they were theoretical or review articles. At this point, the full-text versions were retrieved online. At this stage, 3 articles were excluded because they were not accessible. After conducting a text analysis of the discussion of the findings and conclusion sections, 16 papers did not provide relevant evidence for the topic of interest and were therefore excluded. In the end, a total of 35 articles were thoroughly analysed.

This review adopts some elements of the framework-based synthesis methodology which is based on using an already established conceptual framework for synthesising the literature, adopting a deductive approach (Dixon-Woods, 2011). The selected papers were imported in Atlas.ti, read fully and coded through a thematic analysis. Eight main codes corresponding to Walton’s QWL dimensions were employed. A nineth theme emerged from the text of several articles and was therefore included in the codes list which is shown in Table 1 below. Using this framework allowed to synthesise the literature thematically based on relevant dimensions of work life and to grasp similarities and differences between CSs and traditional workplaces, that is the conventional employer’s premises. However, the use of one database only and the presence of a single reviewer is surely a limitation of this review which should be acknowledged.

The 35 sources are distributed in 32 journals. The figures below show the distribution of the papers based on the year of publication, the country of the researchers, and the methodology used. The year of the pandemic marks a first peak in the publication of articles related to this topic, possibly due to an increased interest on the topic of wellbeing at work and alternative workplaces. As for the countries, the United Kingdom has the highest number of publications (8) followed by Germany and Italy (4). As for the methods used, unsurprisingly, papers mainly rely on qualitative methodology, which is usually the most suitable to answer how questions.

Findings

Safe and healthy work environment

CSs, when compared to homes, are reported to enable workers’ access to an office-like ergonomic work-station. Additionally, as workers in CSs are typically self-employed and responsible for their own equipment, the availability of ergonomic equipment, such as fixed keyboards and mouse or external video terminals, may be limited (Servaty et al., 2018). Coupled with a prevalence of sedentary positions and prolonged use of video terminals in such spaces, this may lead to developing musculoskeletal disorders and vision problems (Servaty et al., 2018). On the other hand, the presence of modular furniture may allow members to change layout continuously based on their needs (Lorne, 2020).

Possibly also in relation to this last aspect, Servaty et al. (2018) reports also a greater physical activity of members compared to traditional offices. Reasons for this are not given but it could be argued that the lack of proper direct control by supervisors as it happens in traditional offices, may encourage coworkers to take more breaks, which are in turn positive for their physical health. Moreover, compared to individual offices, coworking space allow professionals to dedicate more time to their business with a reduced burden to take care of nuisances such as paying bills or dealing with office equipment and stationery. On the other hand, the internal layout of the spaces may present an issue for workers’ privacy needs, for instance to take calls (Vaddadi et al., 2022). Individual social needs for interaction and community may differ widely in CSs (Lashani & Zacher, 2021), and increase stress and time pressure (Servaty et al., 2018). Thus, workers may try to find ways to distance themselves, by locking doors when possible or occupying meeting rooms (Wijngaarden, 2022).

Robelski et al., (2019) points out that the positive evaluation of environmental conditions of CSs may be attributed to the voluntary choice of workers of the space, also possibly based on positive environmental conditions, and that given the great difference among CSs in their layout, size and equipment offered, it is difficult to generalise on their positive effects on health (on this last point, see also Servaty et al., 2018). However, when present, these elements do for sure constitute an important aspect contributing to workers’ wellbeing.

Work-life balance

A key reported feature of CSs is their ability to separate work and other life dimensions. Literature reports the potential of CSs to enable a physical separation between workplaces and homes (Flipo et al., 2022; Merrell et al., 2022), challenging traditional gender roles (Rodríguez-Modroño, 2021), and reducing potential distractions related to house chores and family responsibilities, thereby enhancing workers’ ability to concentrate on work tasks (de Peuter et al., 2017; Merrell et al., 2022; Orel, 2019; Vaddadi et al., 2022). Besides providing a separation, CSs may promote the reconciliation of the different life spheres by offering specific services or facilities such as day care, or giving the opportunity to bring children and pets (Servaty et al., 2018). Finally, when compared to central offices, specifically with reference to dependent workers, CSs have been sometimes associated with reduced commuting time, given their location also in suburbs and peripheral areas, an aspect contributing to improved work-life balance and wellbeing (Houghton et al., 2018; Vaddadi et al., 2022).

CSs are reported to have a disciplining power and to allow workers without statutory working hours to give structure to their work day (Grazian, 2020; Merkel, 2019; Merrell et al., 2022). Work-related discipline comes from seeing other people working and focusing (de Peuter et al., 2017). Although they are generally considered to be less noisy than third places such as cafes and restaurants, CSs’ internal layout and construction materials, and the potential lack of rules of conduct, may make noise an issue, as reported by several studies (Houghton et al., 2018; Robelski et al., 2019; Servaty et al., 2018). Noise and disturbance may hinder cognitive weariness, namely the difficulty to concentrate on cognitively demanding tasks (Van Horn et al., 2004). Routines and rituals in CSs may help build a specific temporality (i.e. silence can be broken to ask other members for coffee) and spatiality (i.e. common areas like kitchen are nosier than the desks area) for silence and chats, allowing members to not disturb one another (Wijngaarden, 2022). Other studies reported the use of material elements for avoiding distractions, namely the use of phonebooths and meeting rooms for calls, and listening to music through headphones (Cruz et al., 2021; Grazian, 2020).

Finally, the opening times adopted by CSs may influence work intensity and workers’ ability to disconnect, and partly reflect the work culture promoted by the spaces. While some spaces adopt a 24/7 regime to guarantee “massive amounts of flexibility”, with people dropping in and out of the space based on their needs (de Peuter et al., 2017, p. 5), others have fixed opening hours, with members reporting regular working hours, and not keeping working from home or other places once they leave the coworking space (Servaty et al., 2018). As in the case reported by Crovara (2023), hosts may prefer to have fixed office-like working hours as they want CS members “to go home and live” (p.6), a view quite in contrast with the pervasive and passionate start-up culture found in other spaces (Papageorgiou, 2020).

Social significance of work and work culture

The work culture promoted by CSs may vary across spaces. According to Orel & Kubátová (2019), members tend to perceive CSs as a reflection of their lifestyle and values. However, the degree of identification of members with CSs values may vary a lot, based also on the duration and continuity with which workers use these spaces, and on whether they actually adhere to the value promoted. In other cases, members may change their values and work culture under the influence of CSs as thoroughly shown by Bandinelli (2020). CSs work culture and values are expressed materially through interior design and decorative choices, through magazines on shared tables, posters hanging on the walls and celebrating a certain ethos that can be summarised in the “Do what you love” motto (de Peuter et al., 2017; Merkel, 2019) materialised into the WeWork’s flag and even on maintenance workers t-shirts (Grazian, 2020). Other times, the CS culture could be more relaxed and less prone to business matters, as in the case reported by Bosworth et al. (2023) where one member who kept wanting to discuss business rather than socialising was perceived to be out of place, and in the one reported by Nielsen & Mangor (2022) where a member’s Facebook post on the CS’s group on how to achieve financial success became object of criticism by several members of the CS community for whom money was not that important as an aspect of their work life.

Not adhering to a certain ethos may bring to exclusionary mechanisms or to push members to change their behaviour to adhere to accepted practices. This is not valid only for work culture but also for other values promoted by CSs. The example of the “sexy salad” event reported by Bandinelli (2020) is particularly iconic in this sense. This lunch event organised at Impact Hub Westminster entailed each member bringing an ingredient for a salad, and one of the newest members brought meat, which was considered inappropriate from the other members who were probably expecting healthier ingredients. Members’ comments made not only the newcomer feel out of place but had also a disciplining power in making him reconsider his choices for future events to be more in line with the community’s culture and values.

Besides work culture, CSs may promote other values by engaging in socially responsible practices, such as promoting and implementing correct waste management and car sharing services (Orel & Kubátová, 2019), organising events promoting social enterprises and corporate social responsibility practices (Lorne, 2020), and through using second-hand furniture and similar environment-friendly practices (Bosworth et al., 2023). CSs may also engage with the local community, including more vulnerable groups such as the elderly, by organising events, and offering services to a wider audience rather than strictly to members (Akhavan & Mariotti, 2022; Bosworth et al., 2023). Such socially responsible behaviours seem to be valued positively by members (Akhavan & Mariotti, 2022; Orel & Kubátová, 2019). In rural and peripheral regions, CSs may embed the higher purpose of local development and of reconnecting rural and urban areas (Bosworth et al., 2023; Flipo et al., 2022).

Integration into the work community

The work community in CSs is the most discussed aspect in the analysed literature. The promise of a community within CSs has become an important selling point for CSs’ owners (de Peuter et al., 2017; Gandini & Cossu, 2021; Wright et al., 2022). Akhavan & Mariotti (2022) points out how coworkers’ satisfaction is related to social proximity, that is to friendly and trustworthy relationships with the other members. Indeed, CSs are chosen over homes for their potential to decrease professional and social isolation and act as sources of support (Avdikos & Kalogeresis, 2017; Bosworth et al., 2023; Lescarret et al., 2022; Rese et al., 2021), and represent an occasion for socialising beyond business networking and collaboration (Bosworth et al., 2023; Brown, 2017; Flipo et al., 2022).

The effective construction of a coworking community is a collaborative process made up of distinct phases (Rus & Orel, 2015) in which the mediating role of hosts is fundamental and highly valued by members (Kozorog, 2021; Merkel, 2019). For instance, the organisation of events by CSs hosts may contribute to the integration of members in the coworking community (Bandinelli, 2020; Wijngaarden, 2022; Wright et al., 2022). However, successful integration may also depend on the extent to which events are actually curated, since simply organising happy hours and similar social events without facilitating interaction, could lead to people leaving after some minutes, staring at their phones or talking only to the people they already know (Grazian, 2020).

Another aspect contributing to the integration into the work community is the internal layout and design of CSs, including open spaces, modular furniture which allow for eye contact and people sitting relatively close to each other, facilitating social interaction and collaboration among members (Servaty et al., 2018; Wright et al., 2022). Common areas (i.e. kitchen, outdoor and smoking areas) are particularly important to socialise and share knowledge, together with specific sites for relaxing, such as table-tennis tables (Bosworth et al., 2023; Fuzi, 2015; Wijngaarden et al., 2020). Another factor contributing to the integration within the coworking community has been reported to be the use of ICTs, especially Slack or similar tools to discuss common topics of interest (Wright et al., 2022).

As seen in the previous section, integration in the community is facilitated by the shared values and experiences of members, lifestyle and even political ideas (Mariotti & Akhavan, 2020). Given the similarity of members’ professional conditions, workers feel they can find people “with same concerns and problems” (Rodríguez-Modroño, 2021, p. 2269). Community membership is also sometimes curated by the hosts who decide whether to admit or discard a new membership request. In sectorial CSs, hosts tend to accept members of a specific sub-sector usually within cultural and creative industries, while in other cases hosts prefer to guarantee a diversity of members in terms of professions, in order to enhance cross-sectoral collaboration (de Peuter et al., 2017; Lorne, 2020). Besides similarity on values and work culture, the adherence to certain rituals and unspoken rules is also important for members’ integration into the CS community (Wijngaarden, 2022).

Homophily in CS communities in terms of sociodemographic features, such as gender and class, is also reproduced and encouraged by material features such as decorative elements, gendered playing gear, and membership fees (Grazian, 2020; Lorne, 2020). Such similarity has also limitations, since it may enable peer pressure and exclusionary mechanisms toward those who don’t fit (Lashani & Zacher, 2021; Lorne, 2020; Wright et al., 2022). Accessibility and openness of CSs is sometimes more of a myth than a reality, as also the material boundaries (security doors, online tools for registering, and similar technologies) separating the CS community from the rest show (Lorne, 2020).

Applying and enhancing one’s skills and possibilities for continuous growth and stability

CSs represent an attractor for professional development reasons (Merkel, 2019). In terms of ability to apply one’s skills, the available literature finds positive correlation of the material environment of CSs (such as a fast internet connection, but also the design and aesthetics of the space) and the interaction and networking with other members with workers’ creativity, the quality of work performed and the time employed to perform tasks (Bueno et al., 2018; Rese et al., 2021).

The role of networks for job finding has been vastly highlighted in economic sociology literature (Granovetter, 1973). The instrumental function of social connections at work is particularly visible in CSs, where know-how is transmitted many times horizontally and where contacts constitute social capital, in terms of access to potential clients, referrals, and professional collaborators. And indeed, this is one of the primary reasons for joining a space (Fuzi, 2015; Merkel, 2019). Working in a CS may also allow workers to perform professionality, with the consequent advantage of taking up more important projects, as they have the possibility to receiving clients in a dedicated space (Merrell et al., 2022).

Learning and knowledge exchange processes leading to career and professional development may be organised top-down or occur horizontally through curated and spontaneous interaction among CS users. Hosts may organise training courses on specific skills for their members (Pacchi & Mariotti, 2021; Wright et al., 2022), thus shadowing traditional work organisations providing learning and training for employees. Moreover, members may ask support to other members of the same or other professions to get advice and new perspective on problems in their daily work (Hysa & Themeli, 2022), may ask for information for advancing one’s career, share knowledge and know-how (Merrell et al., 2022; Nielsen & Mangor, 2022; Wright et al., 2022). Bosworth et al. (2023) reports how CSs may provide also training opportunities in digital skills and jobs for young people in rural areas who would otherwise need to leave their place of origin to pursue the same opportunities.

In terms of career stability, some studies report a more static role of CSs, which act more as shelters rather than springboards for precarious workers to pursue a more stable career (Pacchi & Mariotti, 2021), sometimes offering temporary remedies, such as using another member’s social insurance to invoice clients when workers are uninsured (Avdikos & Kalogeresis, 2017). Other studies describe CSs to take a more dynamic function, considering that interacting and observing other members may also contribute to workers’ acquisition of business skills, especially for recent graduates who have not been trained in this sense and are not enough experienced to master them (Wijngaarden et al., 2020). Moreover, interacting with other members and attending training courses may also facilitate career changes, such as professional transition of members from employees to self-employed (Flipo et al., 2022).

Fair and adequate compensation

As just discussed, CSs constitute sites for strategic ties building, as they act as facilitators of workers’ accumulation of social capital which in turn can convert into economic capital (Gandini, 2015), possibly improving workers’ economic conditions. From the review it emerges that both curated and un-curated interactions may develop into paid collaboration and opportunities for workers, especially for freelancers. There is an effort in CSs to cover the demand any member may have for a specific job with internal resources (Avdikos & Kalogeresis, 2017; Bosworth et al., 2023). Building strategic ties with others is an aspect deeply bounded with the “integration in the work community” dimension as jobs are given to “friends” (Bandinelli, 2020).

Exchanges taking place among members may also constitute diverse economies (Gibson-Graham, 2008), taking unusual forms (i.e. barter, favour swapping, etc.) (Wright et al., 2022). Such exchanges may take place across different career levels, for instance more experienced professionals may pass some projects to less experienced ones when they consider the jobs as too small for them (Wijngaarden et al., 2020). Moreover, sharing specialised equipment with others may allow members to abate cost while having more chance to get in (possibly better-paid) projects requiring such specific tools (Avdikos & Kalogeresis, 2017). Informal transactions may also involve hosts, who may offer free desks in exchange for some services (i.e. the development of a campaign for the space, see Nielsen & Mangor, 2022). When the relationships developed among members present power unbalances, they may result in unpaid labour exploitation, or in working below the market rate (Wright et al., 2022). Sometimes, rather than being sites of informal yet reciprocal exchanges, CSs may also house hope labour (Kuehn & Corrigan, 2013), where unpaid labour is undertaken in the hope for future paid jobs and increased revenues (Nielsen & Mangor, 2022; Papageorgiou, 2020).

Constitutionalism in the workplace

CSs are rarely considered “a response to precarization” (de Peuter et al., 2017, p. 8). As seen, the work ethos emanating from large coworking chains tends to be individualistic and entrepreneurial, according to which work-related challenges, such as income insecurity and low earnings, are faced resorting to the market rather than to collective fights (Lorne, 2020; Merkel, 2019; Pacchi & Mariotti, 2021). At the same time, acknowledging the ambivalence of CSs, de Peuter et al. (2017) recognises the potential of CSs in providing a political space, beyond a space for work and socialising, for independent and solo self-employed workers, given the bottom-up and self-organised roots of the coworking phenomenon outside of unions that still fail to represent independent workers. Along this line, de Peuter et al. (2017) and Merkel (2019) report of a few events organised within CSs which tackled issues of precarity and financial challenges, while Ivaldi et al. (2021) reports of a coworking space born within workers’ union’s offices, with the aim of promoting values of dignity and inclusion for all workers.

Even though CSs do not seem to offer a safety net for independent workers (Avdikos & Kalogeresis, 2017), several papers report of CSs offering childcare services, and similar social protection tools, in the lack of the availability of the same services offered by employers and the state (de Peuter et al., 2017; Merkel, 2019; Servaty et al., 2018). Nevertheless, research on these issues and the way CSs may contribute to advance independent and unstructured workers’ rights is still lacking. While the available papers mainly focus on self-employed workers, CSs may also become places featuring and promoting workers’ rights connected to flexible working schemes for dependent employees, especially following the Covid-19 pandemic.

Discussion and conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to explore the ways in which CSs may affect the wellbeing and QWL through a systematic review of the academic literature. A comprehensive search using Scopus resulted in a total of 35 relevant papers published in peer-reviewed journals. By employing a conceptual framework commonly adopted to study traditional workplaces, this paper attempted to uncover the similarities and differences between standard workplaces and CSs. Overall, the analysed literature showed that CSs may emulate traditional workplaces, contributing to various aspects of members’ QWL. From providing a safe and healthy workplace to offering childcare services, and facilitating both horizontal and vertical opportunities for training and skills development, CSs may provide an infrastructure to potentially enhance workers’ QWL and wellbeing.

CSs are diverse in terms of user base, layout, services offered, accessibility, ownership, curation practices, and location. While generalising the impacts of these spaces on individual users is challenging, this review sought to identify several aspects of CSs that can differently affect workers’ daily lives. The paper identified several tangible elements together with “less visible components” (Aslam et al., 2021, p. 2028), such as ICTs, as potential facilitators or obstacles to workers’ wellbeing. In particular, the internal layout of CSs, including the presence of open-planned spaces, common areas, leisure and day-care facilities, meeting rooms and phone booths, can influence workers’ work-life balance, ability to focus, and the potential interaction for different purposes among members. Moreover, office equipment, decorative elements, and technologies regulating access to the space, may also affect the experience of individual members, both in terms of physical and social comfort, as these elements may reflect a specific work culture, and may favour or not a certain level of homogeneity within CSs’ user base. These material elements are closely knitted with hosts’ curation practices, rituals, routines of the CS community and individual users’ behaviours.

Although QWL dimensions have been presented separately in this review, they are instead deeply interconnected. The integration of members into the CS community is deeply bounded to their adherence to shared values (including work culture), practices and rituals that enable a successful integration. In turn, being an integrated member opens up access to learning and development opportunities, as well as potential new clients and projects, as jobs are given to friends and known members. However, the reported homogeneity of members in some CSs in terms of gender and class background raises concerns as it may limit the political potential of these spaces as they may end up catering to the most privileged segment of the independent and remote workforce. Low-earning digital workers, such as platform workers, customer service and call centre workers may remain excluded (Tintiangko & Soriano, 2020), while they could greatly benefit from CSs on different levels. One of the main barriers may be membership fees, which, if lowered, could enhance accessibility and inclusivity (Sargent et al., 2021). Failure to address these issues by policymakers, practitioners, and employers alike could result in CSs becoming privileged bubbles for highly-earning professionals, thereby reinforcing existing social inequalities.

Another important aspect that emerged in the literature is the wider spatial dimension of CSs. The value of CSs for individual work lives is also deeply connected to the spaces’ location. Preliminary evidence suggests that CSs in peripheral areas may have different characteristics and act as social infrastructures (Avdikos & Merkel, 2020; Gandini & Cossu, 2021; Tomaz et al., 2022), contributing not only to QWL but also to the overall quality of life of the wider local community. Research pointed out how living and working in a peripheral area may positively or negatively affect workers’ daily lives (see Alacovska et al., 2021; Hracs et al., 2011; Oakley & Ward, 2018). Indeed, a slower work pace, a reduced competitiveness may not only reduce stress but may also increase the chance of enhancing workers’ earning opportunities. Additionally, the lower cost of living, housing and workplaces (including paying a desk or an office in a CS) may also improve workers’ quality of life overall. However, the absence of urban-like networks in more sparse regions may hinder workers’ access to fairer and more stable earnings and career advancement opportunities. In this regard, CSs may serve as essential spaces for building professional networks in these areas (Bosworth et al., 2023). Merrell (2022) suggests that working from a rural location adds another beneficial aspect, that is access to green spaces and the presence of therapeutic landscapes (Finlay et al., 2015), which can contribute to workers’ work-life balance and quality of life more in general. Nevertheless, research on the functioning of these spaces located outside large urban agglomerations and their potential implication for workers’ wellbeing is still limited. Future research could therefore address this gap by merging the ongoing debates on the future of work and that of rural areas.