Introduction

The ongoing changes in the work field, driven by digital technologies and knowledge-based economies, have given rise to the emergence of new working spaces characterized by flexible and autonomous practices (Constantinescu & Devisch, 2018; Eurofound, 2020; OECD, 2016) Governments have actively pursued strategies to attract creative and entrepreneurial individuals and businesses, aiming to enhance innovation and competitiveness through transnational networks of knowledge transfer and policy (Brenner et al., 2010). CWS have been integrated into urban development strategies as deliberate efforts to leverage their potential in fostering knowledge sharing and business collaboration. These spaces offer accessible and affordable alternatives to traditional offices, making them particularly attractive to early-stage ventures and self-employed workers.

This study focuses on the historical and spatial evolution of CWS within the municipality of Lisbon, Portugal. Specifically, it examines the interplay between local government strategy and private initiatives to understand the dynamics that have driven the emergence and growth of CWS in the context of Lisbon’s urban development.

The mapping and spatial distribution of CWS in the city allows the analysis of factors such as proximity to transportation hubs or business areas shedding light on the patterns and dynamics of coworking spaces in specific urban contexts, as well as their distribution patterns concerning office supply zones and the main public transport facilities.

The research questions that guide this study are:

i) What are the key phases and critical moments in the development of CWS in Lisbon, and how have they influenced the current landscape in terms of distribution and sectors of CWS in the city?

ii) How have local government strategies and private initiatives influenced the development, location, and resilience of CWS in Lisbon, taking into consideration the impact of global events such as the 2008 economic crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic?

To answer these questions, several important aspects are explored in the case study analysis:

i) the emergence, different stages, and significant milestones in the development of CWS in Lisbon, with a particular focus on the effects of the 2008 economic crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic on the growth, closure, and diversification of these spaces;

ii) the role and diversity of strategies, programmes, and initiatives implemented by various stakeholders in relation to CWS;

iii) the identification of CWS locations, sectors of activity, and their distribution in relation to points of interest on OpenStreetMap, as well as their proximity to metro and train stations in Lisbon.

To achieve these goals, the research methodology employed in this article involves qualitative content analysis of articles and policy and planning documents as well as semi-structured interviews with key informants (4) to understand the strategies, programmes, and initiatives that supported and promoted the development of CWS; semi-structured interviews with experts and coworking operators (22) conducted in the period between 2020 and 2022 through a combination of videoconference and face-to-face methods. Additionally, site visits to CWS in Lisbon (10) were carried out once the lockdowns were lifted. Moreover, diverse sources of data were used to build a georeferenced database of CWS allowing spatial analysis to identify and examine the development and distribution of CWS across the city’s neighbourhoods over time.

Thus, the article aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the CWS phenomenon in the scope of an ongoing international research project focused on comprehending the dynamics and location of new working spaces and the expanding workforce within the knowledge and sharing economy framework.

As research in this field is still at an early stage, further studies are needed to fully understand evolving practices and their specificities and long-term impacts on the local context, and to confront them with other variables and realities.

Literature Review

Over the past two decades, there has been a remarkable global expansion of new workspaces as an alternative to traditional offices, working from home, cafes, or other ‘third places’ (Oldenburg, 1989). Among these spaces developed within knowledge and sharing economies, CWS have become almost ubiquitous, presenting a range of objectives and operational models to accommodate market demands. Originally conceived as collaborative environments fostering project collaboration, knowledge sharing, and social interaction among creatives, entrepreneurs, and businesses, CWS have attracted the attention of policymakers, urban planners, academics, and practitioners. Numerous studies have been conducted to explore this phenomenon from various perspectives, improving the understanding of these dynamics and their impacts in different regions and contexts (Bednář & Danko, 2020; Boutillier et al., 2020; Capdevila, 2015; Cheah & Ho, 2019; Di Marino & Lapintie, 2017; Gandini, 2015; Huang et al., 2020; Mariotti et al., 2017, among others; Mariotti & Pacchi, 2021; Pacchi, 2018)1. Several analyses have examined the relationship between coworking spaces and innovation, entrepreneurship, and competitiveness strategies, highlighting how these spaces facilitate knowledge sharing, collaboration, and the exchange of ideas among diverse individuals and organizations (e.g., Boutillier et al., 2020; Cabral & Winden, 2016; Capdevila, 2014; Merkel, 2017; Moriset, 2014; Spinuzzi, 2012). The literature has also shed light on the interaction between top-down processes promoted by governments in many cities, driven by challenges arising from successive crises, and bottom-up interventions (Fiorentino, 2019). Strategic alliances have been established between public and private actors, including start-ups, research institutes, and government agencies, with the aim of promoting local innovation ecosystems to attract talent, investment, and infrastructure development. Furthermore, CWS are often located in inner cities, which reflects the desire to be close to diverse amenities, services, and networking opportunities (Di Marino et al., 2022). Moreover, CWS have become instrumental in urban regeneration projects and in the revitalization of underutilized or neglected areas to create vibrant neighbourhoods. By attracting entrepreneurs, startups, and creative professionals, CWS play a key role in diversification and economic growth of local economies in fostering a dynamic ecosystem for innovation and collaboration among diverse professionals and industries (Durante & Turvani, 2018).

The 2008 global economic crisis and the recent COVID-19 pandemic have had profound effects on the work field. These crises have accelerated the demand for flexible and adaptive workspaces, leading to a significant increase in the popularity and adoption of CWS. Individuals and companies sought solutions that provided flexibility, networking opportunities and cost-effectiveness. CWS have emerged as viable options, offering a supportive environment for remote workers, freelancers, and small businesses to thrive, but also in response to a growing number of companies and large corporations also beyond central areas of large metropolises.

In Portugal, as discussed in the next section, the growth of CWS was observed in the context of economic recovery and initiatives supporting entrepreneurship and innovation, closely linked to the startup scene aiming to promote city attractiveness and competitiveness. Like other European capitals, Lisbon has been actively fostering the development of a creative and entrepreneurial ecosystem, including the establishment of a network of incubators, fab labs, and CWS.

The development of Lisbon’s entrepreneurial ecosystem

The 2008 global economic crisis and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis in Portugal had a profound impact on employment, resulting in an increase in the unemployment rate until 2013, when this trend was reversed. At the same time, self-employment, which had been in decline since 2007, had a slight increase from 2011 to 2013 before falling slightly again2. Several key informants interviewed point to a growing number of professionals, particularly in the creative and ICT sectors, who opt for self-employment.

In the context of this crisis, the Lisbon City Council defined a long-term vision to boost the city’s development. As outlined in the Municipal Master Plan, this strategy was set to “promote an innovative and creative city, capable of competing in a global context and generating wealth and employment” (CML, 2012, p. 37). By emphasizing the promotion of innovation and creativity, the PDM seeks to create an enabling environment for entrepreneurs and businesses in various sectors, thereby contributing to economic growth and job creation.

The development of this strategy was not an isolated endeavour, it was rather built upon various precursor initiatives. They included the establishment of the National Association of Young Entrepreneurs (started in 1986), the Lisbon Incubator Network (a set of existing incubators in the city but promoted as a network since 2013 by CML), and a range of projects in creative industries initiated by micro and small private entrepreneurs.

The implementation of the city’s strategy required collaboration between public and private actors, with substantial contributions from diverse stakeholders. As highlighted by one of the interviewees, local officials sought a more fluid and collaborative approach, encouraging all stakeholders to actively respond to the city’s challenges (key informant #4, 21 June 2020).

The Municipality of Lisbon, as a key player in developing and implementing this strategy, established a dedicated municipal department for the Economy and Innovation sector and participated in several European cooperation projects. One of these projects, entitled Cross Innovation3, focused on the interaction between the creative industries and other industrial sectors, which, as one of the interviewees stated, “was very beneficial in terms of learning, namely through the meetings held in different cities, with the presence of entrepreneurs” (key informant #5, June 14, 2020). This type of project helped to develop valuable tools, such as Lisbon Creative Brokers, a platform to facilitate networking and cross-innovation between the creative industries and other sectors while also identifying strategic clusters and fostering the development of the entrepreneurial ecosystem under the Made of Lisboa brand.

“It was the evolution of the ecosystem that led to the creation of Made of Lisboa platform in 2016 … as part of the strategy of the municipality to federate this ecosystem and create interaction and multiple dynamics of value” (key informant #2, March 21, 2020).

Furthermore, in 2009, the City Council, in collaboration with the Portuguese Chamber of Commerce, established Invest Lisboa, an agency responsible for identifying potential business partners, investment opportunities, suitable facilities, and access to various support programmes like Lisboa Empreende.

A pillar to this strategy was to transform Lisbon into a Startup City of international reference. The project Startup Lisboa was born within this framework and as part of an urban regeneration project in the downtown area (Baixa).

“We wanted it in downtown ... that would attract people to this area... that would act as an anchor in the revitalization of downtown, a space open to all that interacted with the rest of the ecosystem” (key informant #5, Jun 14, 2020).

This project was one of the most voted in 2009/2010 Participatory Budget of the City Council, being inaugurated in February 20124. Startup Lisboa offers incubation programmes, events, CWS, and other facilities to entrepreneurs, primarily in the tech, commerce, tourism, and services sectors. Subsequently, a residence was integrated into the initiative in July 2015.

In recognition of this strategy, in June 2014, Lisbon received the European Entrepreneurship Region 2015 award, and the city began to host events such as Coworking Europe 2014 and the Web Summit (since 2016), among others.

In parallel, the Lisbon City Council also began to operate a network of complementary facilities, including Fablab Lisboa (since 2013), which provides digital fabrication and prototyping tools to foster innovation (Gaeiras, 2017); the creative incubator Mouraria Innovation Center (established in 2015) as part of the regeneration strategy of the Mouraria quarter; Pólo das Gaivotas (founded in 2015), a center for artistic creation with rehearsal spaces, offices, and training space; and the Mercado de Ofícios do Bairro Alto (established in 2018), a former market repurposed to accommodate the Arts and Crafts Network.

An important project that is being developed for entrepreneurs and innovators is the Beato Creative Hub, a former industrial space of the Portuguese Army with 35 000 m2 and more than 20 buildings. This area in the eastern part of the city is described as “a gap between the city center and Parque das Nações (…) decadent and depressed, in need of a huge revitalization” (key informant #5, Jun 14, 2020). Managed by Startup Lisboa, it seeks to position Lisbon internationally and to attract investments and skilled professionals to benefit the entire local economy (key informant #3, April 21, 2020). Despite delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the global economic context, this creative hub is expected to offer diverse workspaces, events and retail options, maker spaces, coliving facilities, and a museum, among other amenities. The surrounding area is undergoing significant transformation, with an increasing number of CWS settling nearby.

Aligned with this strategy, Portugal has gained significant international visibility, primarily due to its safety, quality of life standards, labour costs, and pleasant climate, among other factors5. The foreign resident population has consistently grown in recent years6, reaching 108,894 foreign citizens residing in the Lisbon Municipality in 2021, accounting for almost 20% of the total population7. The dynamism around startups and technology companies, the availability of specialized talent, and government support initiatives have contributed to attracting more and more workers, entrepreneurs, and remote companies and, consequently, to the development and diversification of CWS in the city.

Therefore, the development of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Lisbon was the result of a collaborative effort between public and private actors, with the Municipality of Lisbon playing a leading role in defining and implementing the strategic vision to enhance the city’s image and global positioning. Besides, CWS and other facilities were instrumental in fostering the development of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Lisbon. They provide infrastructure and an environment for entrepreneurs, startups, and freelancers to work collaboratively, thereby contributing to the city’s competitiveness in attracting remote workers and investments.

The emergence of coworking spaces in Lisbon

The emergence and growth of coworking spaces in Lisbon can be seen as part of broader global trends. Many cities, including Lisbon, have indeed embraced a knowledge-based urban development paradigm recognizing the importance of fostering innovation and promoting economic growth by attracting talent and investments (Carrillo et al., 2014; Yigitcanlar et al., 2008, among others).

The emergence of the first formally designated CWS in Lisbon can be traced back to 2009, a period marked by the impact of the global economic crisis. During this time, the Portuguese economy faced challenges and witnessed a rise in the number of self-employed workers and entrepreneurs, as mentioned earlier. These individuals sought out spaces that offered shared resources, networking opportunities, and cost-effectiveness as the two cases presented below illustrate.

However, informal coworking had already been taking place, as one key informant mentioned:

“Some already did coworking despite not using the term. Coworking without a hyphen, to demarcate from the spaces of pure entrepreneurship (incubators, accelerators, etc.) and renting tables..., where work is not the only motivation to be there” (key informant #4, Jun 21, 2020).

One of the earliest spaces was Liberdade 229 (figure 1), created in June 2009 and closed in 2021. The need to share rental expenses led the web development company Quodis to launch this creative workspace. Located on the second floor of a nineteenth-century building, just steps away from the subway, on one of the most important and luxurious avenues in the capital, with six rooms, 34 desks, and 24/7 access to freelancers and entrepreneurs, primarily in digital and creative industries. Approximately one-third of the coworkers were international, and the space was carefully designed with artworks, entertainment areas, a ping-pong table, a Super Mario Bros console, and a spacious kitchen.

Coworkinglisboa (figure 1), founded by Ana Dias and Fernando Mendes in February 2010, played a pioneering role in spreading the coworking movement throughout Portugal and Lisbon’s creative ecosystem. It was located in LxFactory, a temporary project in a deactivated industrial complex awaiting urban plan approval for that city area. Fernando Mendes, a freelance designer in contact with the emerging coworking actors at the European level, was searching for a space where people could work and collaborate instead of being alone at home. The project motto: “It’s no longer about work” emphasized the strong community and cooperative spirit among designers, architects, programmers, marketers, and others (about 30% were foreign companies). LxFactory, which had become a particularly trendy and desirable place in the city, was bought in 2017 by French Keys Asset Management8. The increase in the value of rents led to the closure of Coworklisboa at the end of 2019, which moved to a new open space in the Beato area, the NOW_No Office Work.

LIBERDADE 229 (2009). https://liberdade229.com/meeting-2-xlarge.jpg (left); COWORKLISBOA (2010). Available at: https://workfrom.co/coworklisboa-lisboa-34449 (right)

Figure 1 The first recognized CWS in the city of Lisbon

Despite the fact that the development of CWS in Lisbon initially lagged behind other major cities, the Portuguese economy recovery produced a gradual increase in the number of coworking spaces, peaking in 2018/2019 (see Table 2 in the next section). The popularity and expansion of coworking spaces in Lisbon are also closely linked to the city’s urban planning and development strategies, with an increase in the number of operators entering this market segment. Some operators are part of the global coworking industry and include the well-known Regus, Spaces, Impact Hub, and Second Home, among others. There are also smaller and independent coworking space operators that cater to specific niches or communities.

As one key informant explained:

“Local market conditions contributed to the establishment of CWS. They were cheaper for users, rewarded the promoter more, favoring mainly those who made it with quality, design and creative environment” (key informant #1, April 21, 2020).

In March 2020, the crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic imposed new challenges and demands on work-life routines. To mitigate the spread of the virus, the Portuguese Government took several measures, such as the general duty of confinement, the closure of non-essential services, and the imposition of telework whenever professional functions allow. During this first lockdown, many CWS closed or reduced users’ physical presence, improving their services online to continue to support their communities. As described by one of the interviewees:

“We were forced on negotiating the rents of these spaces. At first, it was difficult, but then we all realized there had to be adjustments. We created new forms of communication and new business solutions, through virtual offices, for example, … we adopted safe rules and social distancing, etc.” (key informant #4, Jun 21, 2020).

If until the beginning of the pandemic, teleworking had increased timidly for decades in Portugal9; from April to December 2020, this number increased to 15.6% of the total employed population. The Lisbon Metropolitan Area registered the highest proportion (27.9%), concentrating 48% of the employed population in telework concerning the country’s other regions.

Some CWS were just getting started when the first lockdown occurred, leading to delayed openings or closures. However, after the forced slowdown in the first year of the pandemic and adjustments, particularly in price and accessibility flexibility, most visited and interviewed CWS anticipated greater demand from companies and workers in remote and hybrid work modes. As some of the interviewees mentioned, freelancers, who are the primary users of CWS, were already accustomed to working remotely for international markets. Moreover, they anticipated increased demand for remote and hybrid work both from companies and workers. However, the long-term verification of these trends and the true impact of the events and policy measures described above still require further examination. Nevertheless, understanding the various stages of development is crucial for contextualizing the current state of CWS and for predicting its possible future trajectories. The forthcoming spatial analysis, which will focus on CWS locations, their distribution in terms of Points of Interest, and transportation networks in Lisbon, will hpefully provide valuable insights into how specific factors impact CWS development and influence urban dynamics.

In the context of analysis of the development of CWS in cities like Lisbon, it becomes necessary to engage in a broader discussion regarding the purpose of these new forms of work. These spaces not only blend social and business logics but have also the potential to reaffirm the original ethos of community workspaces (Gandini & Cossu, 2021). By examining the interactions between coworking initiatives, local dynamics, and broader policy frameworks, a comprehensive understanding of the role and significance of CWS in promoting innovation, entrepreneurship, and competitiveness can be attained.

Results of CWS mapping and spatial analysis

A CWS georeferenced database was constructed from May to December 2021 as part of COST Action CA18214. It includes information on their main features (e.g., ownership, business model, types of services provided) and their location (e.g., public transport proximity). The data was collected from existing official data sources (such as Coworker.com, Coworking.no, Made of Lisboa, Startup Portugal) and was combined with media analysis.

The analysis of this georeferenced database shows that in 2021, a total of 92 CWS in Lisbon10 were mostly located in the inner-city parishes and along the city’s main axis of development. The parish of Arroios had the highest number of CWS with 12 spaces, followed by Avenidas Novas and Misericórdia with 10 and 8 spaces, respectively. Conversely, parishes with more residential characteristics had lower numbers of CWS.

Many of the CWS have more than one location in the city, with 34 CWS falling under this category. Some CWS are part of international operators like Regus, which had 6 spaces in Lisbon in 2011. Additionally, 28 CWS in the city are part of Portuguese networks of spaces in different locations across the country, with the most representative being the network of workspaces and coliving called SITIO, which has 8 CWS in the city (Table 1).

Table 1 Number of locations in the city and CWS network integration

| Number of CWS | |

|---|---|

| More than 1 location in the city | 34 |

| Only one location in the city | 58 |

| Part of an international network | 17 |

| Part of a Portuguese network | 27 |

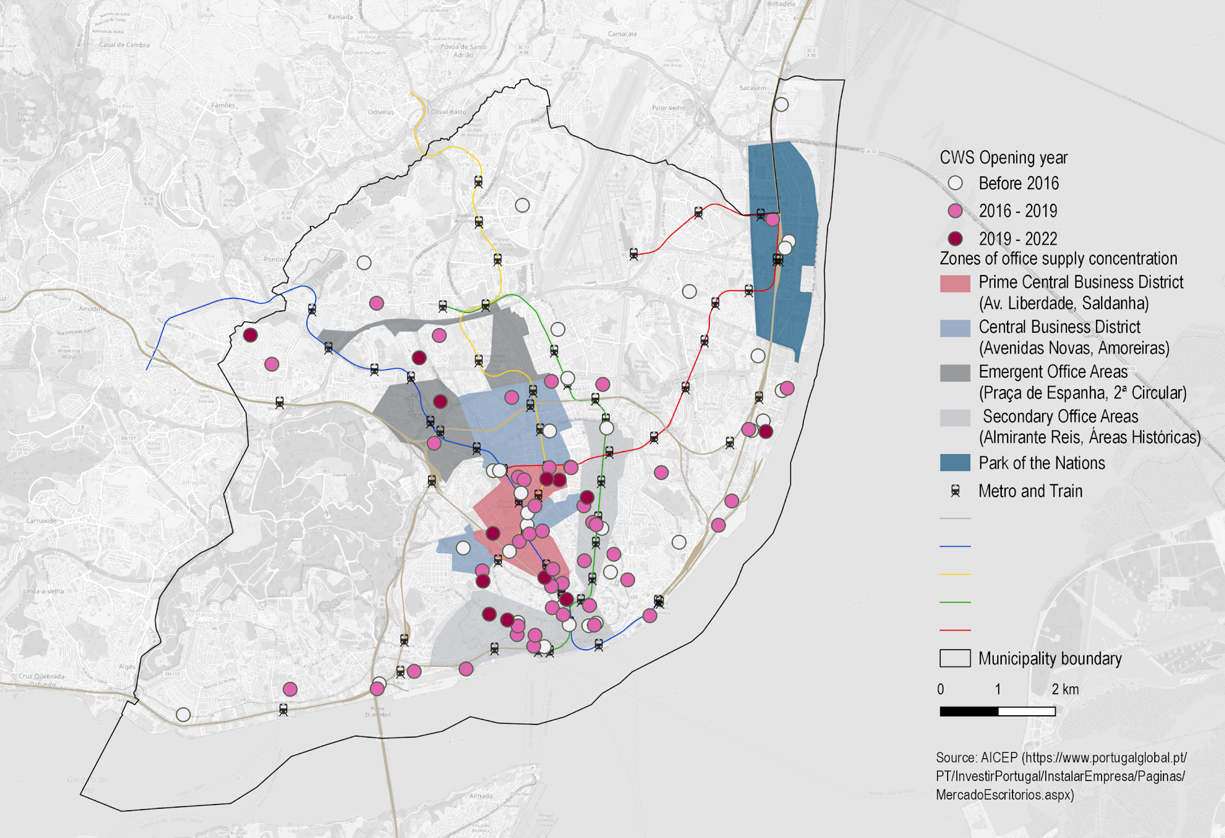

In addition, the location of CWS was analyzed in the spatial structure of the city considering the ‘prime’ locations defined by the office markets, which are usually associated with accessibility issues and proximity to other commercial establishments. This exploratory analysis helped to understand the added value of proximity to customers and suppliers for some CWS. Table 2 indicates the opening year of each CWS, categorized into three distinct periods: prior to 2016, between 2016 and 2019, and between 2019 and 2022, and their distribution in relation to the office supply zones as defined by AICEP Portugal Global - Trade & Investment Agency11, Additionally, Figure 2 illustrates the location of CWS regarding the office supply zones as well as the metro and train facilities.

Table 2 Location of the CWS consistent with the five office supply zones and according to the established time periods

| Until 2016 | % | 2017-2019 | % | 2020-2022 | % | TOTAL | % | |

| ZONE 1 - Av. Liberdade, Saldanha | 4 | 12,5 | 9 | 20,0 | 4 | 30,8 | 17 | 33,3 |

| ZONE 2 - Avenidas Novas, Amoreiras | 4 | 12,5 | 4 | 8,9 | 0 | 0,0 | 8 | 15,7 |

| ZONE 3 - Praça de Espanha, 2ª Circular | 0 | 0,0 | 1 | 2,2 | 1 | 7,7 | 2 | 3,9 |

| ZONE 4 - Av. Almirante Reis, Áreas Históricas | 7 | 21,9 | 11 | 24,4 | 3 | 23,1 | 21 | 41,2 |

| ZONE 5 - Parque das Nações | 2 | 6,3 | 1 | 2,2 | 0 | 0,0 | 3 | 5,9 |

| Total within zones 1-5 | 17 | 53,1 | 26 | 57,8 | 8 | 61,5 | 51 | 56,7 |

| TOTAL | 32 | 35,6 | 45 | 50,0 | 13 | 14,4 | 90 | 100,0 |

Figure 2 Map of the CWS location in relation to office supply zones and metro and train stations according to the established time periods

The results of the analysis emphasize the following aspects: i) 50% of CWS facilities were established between 2016 and 2019; ii) CWS locations tend to be concentrated in areas with high office supply demand, often in close proximity to metro or train stations; iii) Older CWS (prior to 2016) are relatively more dispersed across the city, not necessarily confined to main office supply areas, and not always in close proximity to metro or train stations.

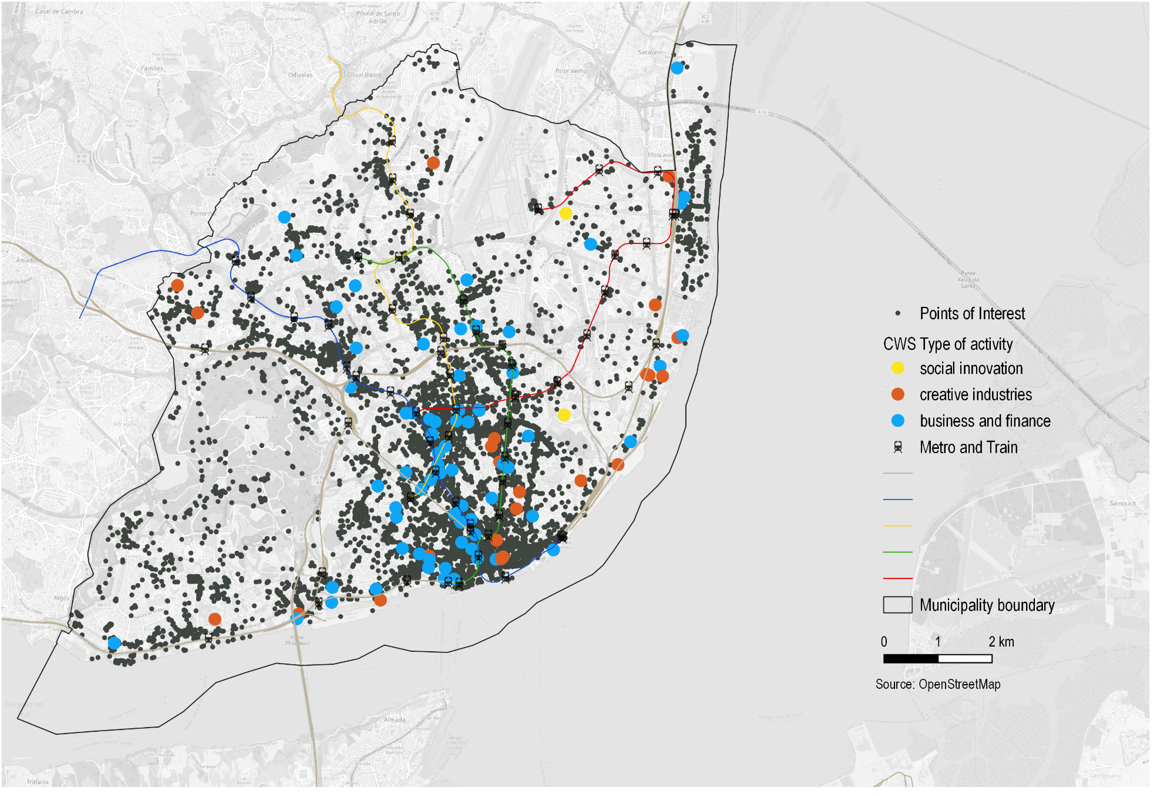

Regarding the type of activities carried out by the CWS, for the purposes of this study, we have classified them into three main categories: Business and Finance, Creative Industries, and Social Innovation. The majority of CWS facilities (71.3%) falls under the Business and Finance category, while only a small proportion (2.1%) is classified as Social Innovation.

While coworking has developed around the idea of a community of like-minded individuals where they can connect, collaborate, and innovate, most CWS have as target people and businesses from diverse industries. The layout of the space and the type of facilities offered configure the type of activity that CWS hosts. Therefore, CWS which are specialized in creative and cultural industries are located mainly in former industrial spaces (especially on the riverside axis), with some exceptions (Figure 3).

Figure 3 CWS location by type of activity and the distribution of the OpenStreetMap Points of Interest

In addition to their preferred location in areas with high office supply concentration, there appears to be a correlation between the location of CWS facilities and the concentration of other Points of Interest12. The proximity and diversity of Points of Interest (POIs) in relation to the CWS in Lisbon were studied by Di Marino et al. (2022). The findings showed that in the central districts of Lisbon, CWS facilities do not benefit from a diverse neighbourhood in terms of POIs. Specifically, the categories of ‘Food and Beverages Services’ and ‘Retail Trade’ were found to be more dominant compared to other categories of POIs. This suggests that the CWS facilities in Lisbon’s central districts are located in areas with a higher concentration of these specific types of POIs, while other categories (‘Entertainment, arts and culture; ‘Public and private services’; ‘Nature leisure and sports’) may be less represented.

Lastly, CWS are changing by attracting more and more investors and corporate clients and offering an ever-expanding set of solutions: from hot desks - in shared space for freelancers, entrepreneurs, and startups, to private flex offices rented to firms of diverse size. They are managed mainly by private sectors, some with different locations in the city. Most CWS are managed by private operators (85), and only a few by public and private non-profit organizations (7).

Conclusions

This study introduces the historical and spatial evolution of CWS in the municipality of Lisbon, Portugal, and explores the interplay between local government strategy and private initiatives in shaping the dynamics and growth of CWS within the city’s urban development context. By examining key phases and critical moments in the development of CWS, as well as the influence of global events such as the 2008 economic crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, this research contributes to a deeper understanding of the CWS phenomenon within the knowledge and sharing economy framework.

The results point to several key aspects of the development of CWS in Lisbon that cannot be dissociated from broader events. CWS are part of glocal dynamics, acting as mediators in the flow of people, knowledge, and innovation.

Firstly, the emergence of the primary formally recognized CWS coincided with the impact of the global economic crisis. As the national economy was starting to recover, the number of CWS experienced significant growth, a trend that continued after the COVID-19 pandemic. This led to the diffusion of these spaces as viable options for individuals and businesses seeking flexibility, networking opportunities and cost reduction. The local ecosystem has witnessed the emergence of a diverse range of spaces, operators, sectors, and practices. This heterogeneity has led to a long discussion around the concept, bringing the ethos of these new forms of work that mix social and business logics in urban planning and development to the centre of the debate.

Secondly, the research highlights the interaction between public and private actors in the expansion of CWS in Lisbon, as in other case studies pointed out in the literature. It emphasizes the important role of local authorities in recognizing the significance of fostering an entrepreneurial and innovative ecosystem through partnerships with public and private entities. The municipality of Lisbon has implemented various supportive initiatives, infrastructure development, actively promoting the city as an attractive destination for investment and talent. CWS are positioned as integral components of the startup and technology landscape, as well as the city’s regeneration policies and projects. By understanding the influence of policies and planning strategies on the evolution of these spaces and the roles played by different actors, policymakers and urban planners can better understand the dynamics and requirements of these innovative workspaces, providing valuable insights for future urban development, the design of effective support measures, and the establishment of sustainable governance models.

Thirdly, the study reveals that most CWS in Lisbon are situated in areas with high demand for offices, often in proximity to subway or train stations, as a result of a combination of factors, including business opportunities, networking potential, accessibility, urban lifestyle, and market demand. However, many CWS focused on cultural and creative industries have chosen former regenerating industrial areas due to the availability of space, competitive prices and potential to offer unique services. In addition, CWS also integrate networks with multiple locations throughout the city, although most mapped CWS are limited to a single space.

By understanding these spatial patterns and trends, the study provides insights into the strategic decision-making behind CWS locations and their potential impact on urban dynamics, including economic diversification and neighbourhood revitalization.

To summarize, this article offers valuable insights into the emergence and spatial evolution of CWS in Lisbon. Further research is necessary to comprehensively examine the long-term impacts and sustainability of CWS due the specificities of local contexts. Additionally, studying the experiences and perspectives of CWS users, operators, and local communities could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the role and effectiveness of these spaces. and their users on city neighbourhoods, as well as their interactions with other urban dynamics, to contribute to inform urban planning and development strategies.

Overall, this research lays the foundation for future investigations that can further expand our knowledge and inform policies and strategies related to CWS, urban development, and the future of work.