Introduction

The ways of working have seen tremendous changes since the early 2000s. This change is closely related to the city economy. With rapid globalization and advanced technologies after the 1990s, new economic activities involving high-level financial services, technology-intensive and knowledge-based firms, and institutions have emerged (Gospodini, 2008). As a result of the knowledge economy, information and knowledge have become fundamental factors in production (Castells, 1996). Knowledge and technology have also changed the ways of working.

The digital era has transformed the economy and ways of working, along with spatial arrangements and the professions of our century. As a result of developments in ICT and changes in the economy, new ways of working, new generations of employees, and new lifestyles have emerged. The workforce of this era mainly comprises knowledge-based workers with a high level of education. Large numbers of workers in knowledge-based professions generally work casually, project-based, and freelance (Gandini, 2015). They are most likely to work in mobile, multi-locational, remote, flexible, distributed, and virtual modes. Wireless networks, laptops, and cell phones also make it possible to work from anywhere. As a result of this mobility, they have a chance to choose where and when they work (Kojo & Nenonen, 2016). Through the use of technology, working environments have moved beyond central office buildings and regular working hours from 9 am to 6 pm have broken down (Laing, 2013). Mitchell (2003) describes the new type of out-of-office working spaces rather than a desktop computer in a specific office as post-sedentary space. In this context, coffee shops, restaurants, libraries, and hotel lounges can become temporary office spaces for such workers. Moreover, new workspaces have emerged in the last two decades for this purpose. Co-working spaces (hereinafter CWSs) are a worldwide phenomenon that emerged as a result of the changes described above.

A CWS is a shared physical workspace and (often) intentional cooperation between independent workers (Waters-Lynch, Potts, Butcher, Dodson, & Hurley, 2016). They are basically open-plan office environments where people work alongside other unaffiliated professionals for a fee (Spinuzzi, 2012). CWSs provide knowledge transfer, informal exchange, cooperation and forms of horizontal interaction with others, as well as business opportunities for its members (Mariotti, Pacchi, & Di Vita, 2017). They create a collaborative community generated by sharing the same environment with other individuals. They also foster information exchange and create new business connections caused by the geographical proximity in such places (Spinuzzi, 2012).

As the different definitions of CWSs emphasize both their physical and non-physical characteristics, the multi-dimensional nature of the concept makes it possible to analyse its different aspects. In this context, a considerable number of academic studies have focused on the typology of CWSs. They basically aim to categorize the types and describe their main characteristics. Such categorization has been made by using different aspects of CWSs such as size, industry and type of operators (Schuermann, 2014), business model and level of user access (Kojo & Nenonen, 2016), level of confidentiality and restrictions on types of users (Bouncken, Laudien, Fredrich, & Görmar, 2017), and their role in the related socioeconomic system (Fiorentino, 2019). Moreover, the managers’ role in and motivation for opening CWSs, the objectives and aims of the CWS, and the types of processes and relationships that the manager promotes and orients inside the space (Ivaldi, Pais, & Scaratti, 2018), locational factors, and membership plans and prices, etc. (Zhou, 2019) was considered when defining the types. Additionally, reviews of the existing literature (Orel & Bennis, 2021) or their characteristics in terms of inspirational workplace design, physical proximity, services, and commitment/risk were assessed in terms of defining the types (Yang, Bisson, & Sanborn, 2019). Nevertheless, such studies still lack a clear assessment when considering both physical and non-physical features of CWSs.

Since co-working spaces are an increasingly popular concept, they are also the subject of many case studies in different parts of the world. These studies are heavily concentrated around European cities, such as South Wales (UK) (Fuzi, 2015), capital area of Finland (Kojo & Nenonen, 2016) and Helsinki Metropolitan Area (Marino, Rehunen, Tiitu, & Lapintie, 2021), Milan (Italy) (Mariotti et al., 2017) and Barcelona (Spain) (Coll-Martínez & Méndez-Ortega, 2020). Studies from Shanghai (Wang & Loo, 2017) and Manhattan, NYC (Zhou, 2019) are also notable. However, studies about Istanbul are lacking and only focused on CWSs as a part of the creative hub concept in general (Parlak & Baycan, 2020) or their situation after the pandemic (Baycan, Parlak Mavitan, & Özcan Alp, 2023).

This paper analyses CWSs in the context of the changing urban environment. It aims to describe the types of CWSs by focusing on the physical and non-physical structures of such spaces. The study provides a general overview of CWSs, which may help to develop urban policies for their emergence. Moreover, it contributes to the existing literature about types and policies by analysing the situation in Turkey, which has thus far not been considered in the academic debate.

The overall structure of the study consists of five sections, including the Introduction, which gives a brief overview of the subject. The second section reviews the definition of CWSs and different approaches to this new phenomenon. The third section is divided into four parts. It begins with an overview of CWSs in Istanbul. It then outlines the aim, scope, and methodology of the research. The last part of this section analyses the results and presents the findings with respect to two topics: the physical structure and non-physical structure of CWSs. The fourth section reveals four different types for Istanbul described as a result of the research. The fifth section contains concluding remarks and further studies.

The emergence of CWSs and different approaches to co-working

Co-working spaces (CWS) have developed as a type of workplace organization of the last two decades. The first CWS emerged as accepted consensus when computer engineer Brad Neuberg organized Spiral Muse in San Francisco in 2005 (Merkel, 2015). The idea grew out of personal experience when Neuberg decided to be a freelancer and asked a friend for an affordable office space (Fuzi, 2016; Jones, Sundsted, & Bacigalupo, 2009). He aimed to avoid the unproductive work life, social isolation, and distraction that can come from working at a home office (Merkel, 2015). After setting up a space for co-working for specific days of the week for a year, it became Hat Factory in 2006 (Fuzi, 2016).

The concept of CWSs is considered in its different aspects in the academic literature. Their non-physical characteristics are distinguishing features while describing them, besides their spatial aspects (layout and architectural features). To this end, CWSs are considered an atmosphere, spirit, or lifestyle (Moriset, 2014), a philosophy or movement (Reed, 2007), and a state of mind (Kwiatkowski & Buczynski, 2011). Capdevila (2013) remarks on the open sharing environment for independent professionals. Similarly, Bilandzic and Foth (2013) highlight the social learning side of co-working, which comes from sharing the same environment for creative activities. Collectivity, collaboration, and networking come into prominence while describing CWSs, beyond the physical services that they provide. Lange (2011) considers them bottom-up spaces and therefore the user profile of CWSs, their approach, and activities become essential. Bouncken and Reuschl (2018) underline the importance of high-level autonomy in CWSs, requiring a non-hierarchical working concept. In this sense, sharing the same working environment with like-minded people (Schultz, 2013) can be considered to enhance the intensity and level of openness, which makes it advantageous to work from a CWS. More broadly, Gandini describes the co-working concept with all its features, from its member profiles to the activities carried out in the spaces (Gandini, 2015).

Networking and collaboration are some of the core elements of the co-working concept. Spinuzzi (2012) views co-working as more than a single activity, working in the periphery of each other’s activities, and emphasizes the importance of network activities within a given space. In this sense, networking and collaboration are an important reason for working in communal places on a contract basis instead of working from home for free and/or renting a personal office space. It can foster new collaborations, creative friendships, sharing of ideas, and networking opportunities on site (Spinuzzi, 2012), while keeping the balance and not forcing people to socialize (Spreitzer, Bacevice, & Garrett, 2015). Being in a community with like-minded people also has physiological importance. One of the main reasons for working at such places is to engage in social interaction and spared social support among independent professionals (Gerdenitsch, Scheel, Andorfer, & Korunka, 2016). The provided opportunities also include the importance of their spatial characteristics.

CWSs are also considered ‘third places’ (Moriset, 2014) or ‘third waves of virtual work’ (Johns & Gratton, 2013). The ‘third places’ concept identifies the places other than the home (first place) and work (second place) for gathering, interacting, and socializing (Oldenburg, 2001). In this sense, coffee houses, pubs, bookstores, etc., are third places, the hearth of social vitality in a community, offering psychological support to individuals and communities. From this perspective, CWSs, as third places, have a strong effect on serendipitous production (Moriset, 2014), which places these spaces beyond just physical spaces. Collaboration affects more than just social solidarity, networking, and creative production. Capdevila (2013) find similarities between collaboration in CWSs and localized industrial clusters, viewing CWSs as microclusters. In this context, entrepreneurs, consultants, freelancers, etc., in these microclusters correspond to firms, organizations and institutions in clusters (Capdevila, 2013).

The effect of CWSs in urban contexts is widely discussed. CWSs are mostly located in the city centres of large urban areas. Their presence affects urban revitalization trends and small-scale physical transformations (Mariotti et al., 2017; Vogl & Akhavan, 2022). On the other hand, peripheral and rural areas are new emerging areas for CWSs (Vogl & Akhavan, 2022). Nevertheless, each city can develop their own location pattern, which makes the location and agglomeration of CWS dependent on the spatial structure of the city (Méndez-Ortega, Micek, & Malochleb, 2022). CWSs tend to be located in specific locations such as neighbourhoods with good public transport accessibility, around university campuses, pedestrian zones, multifunctional districts, and where knowledge-intensive jobs are concentrated (Marino et al., 2021; Mariotti, Capdevila, & Lange, 2023).

As expected, the concept of co-working is associated with economic and ecological terms in the sense of being low-cost, convenient, and eco-friendly (Johns & Gratton, 2013). From an economic perspective, co-working is closely connected to the creative economy due to the reasons such places emerge, their membership profile, the sectors operating in such workplaces, and the activities that take place there. Lange (2011) considers CWSs as a self-governance mode of work in creative industries. He argues that while highly mobile creative workers can rent a micro-work space on a contract basis, they also gain different opportunities such as access to a network and creative milieux. From the sociospatial perspective, sharing the same space creatively is a sort of self-governed reaction to the often-precarious living and working conditions of today’s creative workers, representing an effective solution for crisis-driven times (Lange, 2011). In addition, the cities experience collaborative sharing of space, work places (Laing, 2013) goods and services over the Internet (Bouncken & Reuschl, 2018). Car-sharing, bike-sharing, home-sharing companies are very well-known examples of this model. Office spaces can now be used collaboratively, like renting a bike, home, or car. Laing (2013) discusses that while information technology has changed the ways of working, it has also shifted the acquisition and supply of space. Individuals and organizations can decide where, when, and how to work by choosing the available spaces in the city with mobile services. Even corporate employees have begun to work in CWSs instead of their office buildings. The most critical asset becomes collaboration and people in a workplace. The conventional use of workspaces changes in a way that we have never experienced before.

CWSs in Istanbul

Istanbul is the most populous city in Turkey and the cultural and economic capital of the country. The diversity of cultural resources has direct consequences for culture and creative industries. The creative workforce is primarily concentrated in two cities: Istanbul and Ankara (Lazzeretti, Capone, & Seçilmiş, 2014). Although the creative workforce is still low compared to other global cities, Istanbul hosts the most creative workers in the nation. These sectors mainly include advertising, software, publishing and printing, architecture, filmmaking, design, fashion, and jewellery (Evren & Enlil, 2012). As expected, the infrastructure related to creative workforce is concentrated in Istanbul and as a result, CWSs are significantly clustered there. The city is also the most popular location for global co-working companies such as Regus or Servcorp in Turkey. However, compared to other alpha cities (GaWC, 2020), during the period that this study was conducted (between 2017 and 2020), Istanbul had fewer CWSs. While Istanbul had 59 CWSs for a population of 15,462,452 in 2020 (TUİK, 2020), Madrid had 107 CWSs for 3,265,327 inhabitants (Eurostat, 2020), Chicago had 87 CWSs for 2,746,388 inhabitants (United States Census Bureau, 2020), Toronto had 82 CWSs for 2,794,356 inhabitants (Statistics Canada, 2021), and Milan had 44 CWSs for 6,747,068 inhabitants (Eurostat, 2020) for the same time period (Coworker, 2020). These findings show that Madrid has the highest number of CWS per capita, followed by Chicago, Toronto, Milan, and finally Istanbul. While these results indicate Istanbul may not have fully achieved the same capacity as other similar cities in its category, the city has a growing potential for CWSs considering its positive trend since the beginning of 2015 (Parlak & Baycan, 2020). Moreover, this positive trend continued during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the number of CWSs increased dramatically (Baycan et al., 2023).

3.1. Aim and Scope

This research aims to understand the main characteristics of CWSs in Turkey to describe their different types. Istanbul was chosen as the study area since the city hosts the most diverse and largest number of CWSs in the country. Moreover, the co-working concept is growing in importance in Istanbul (Parlak & Baycan, 2020). Nevertheless, the amount of academic research focusing on the characteristics of such spaces in Turkey is lacking and what research there is only covers CWSs in Istanbul. In this context, interviews were conducted with CWS founders/managers, who were asked to provide information about the structure of their CWS via a questionnaire conducted through face-to-face interviews.

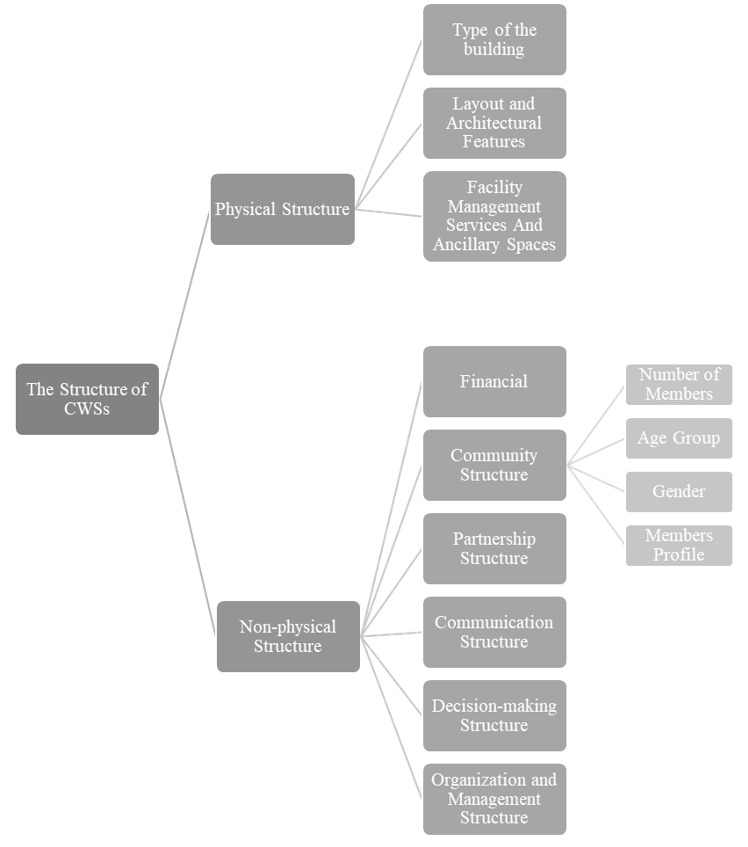

As suggested by the literature, this study considers CWSs more than just physical spaces. For this reason, the CWSs were examined with respect to both their physical and non-physical structure. Open-ended and closed-ended questions in the questionnaire were organized around these topics. The physical structure of CWSs is discussed in relation to the type of the building, layout and architectural features, and the physical services that CWSs provide. The non-physical structure of CWSs is addressed through the financial structure, community structure such as number of members, gender, age group and member profiles, organization and management structure, decision-making structure, partnership structure, and communication structure. The research questions were therefore designed to cover the physical and non-physical structures of CWSs to describe their types. The structure of the research is summarized in the figure below (Figure 1).

The questions regarding the physical structure aim to understand the physical properties of the space, its physical surroundings, and the physical facilities available to members. Questions addressing non-physical features were organized around six macro-themes: finances, community, partnership, communication, decision-making, and organization and management. The questions regarding the financial structure aim to reveal the income model of the CWSs as well as their primary financial resources. Inquires on community structure aim to understand the general member profile, such as age, gender, profession, etc. Questions about organization and management structure help to understand the managerial division and positions in a CWS. This section also investigates the organizations and events that are organized at CWSs. Questions on the decision-making structure aim to know if the decision-making process in CWSs is vertical or horizontal. They also help to understand the role of the members in the decision-making process, as well as the selection process for new members in the community. Questions on partnership structure aim to understand the current partnership projects that CWSs maintain and earlier partnerships during establishment of the CWS. Partnership structure is also associated with the financial structure. Finally, questions regarding communication have two dimensions. The first aims to understand how co-workers communicate with each other within the area. Targeted questions aim to discover if a specific effort is made in this sense or if it occurs spontaneously between members. The second dimension of the questions aims to understand the communication methods the CWS chooses to reveal itself to the world.

Given the above, the research questions are described as follows:

(1) What is the physical structure of CWSs in Istanbul?

(2) What is the non-physical structure of CWSs in Istanbul?

3.2. Data and Methods

The research was conducted in 4 phases. In the first phase, CWSs in Istanbul were investigated through international databases, networks, press reviews, and interviews. This part of the investigation resulted in a list of potential CWSs to contact.

In the second phase, a questionnaire to be conducted via interviews was prepared to analyse different aspects of CWSs and identify their structures. Physical, financial, community, organization and management, decision-making, partnership, and communication aspects were identified to understand the structure of CWSs and the questions were organized around this topic. Accordingly, all CWSs were contacted to schedule a meeting for an in-person interview.

In the third phase, the questionnaires were completed via interviews with the CWSs founders. In some CWSs where it was not possible to meet with the founder, the managers were chosen as interviewees. Interviews were conducted face-to-face and recorded, between June 2017 and January 2020. Some CWSs were visited multiple times, and connection with the managers continued during the research when any additional information was needed.

All the data gathered from the questionnaires and secondary sources were analysed in the last phase, and the empirical results were revealed. The results of the questionnaire were used as the primary data source. Observations, website info, social media account statements, press releases, and brochures supported the main data.

Twenty CWSs in Istanbul were included in the research, covering 87% of CWS locations in Istanbul for the period in which this research was conducted. Considering CWS branches in different locations, a total of 87 locations were included in the research. Only CWSs that agreed to participate in the research were included in the study. The research consisted of CWSs established between 1999 and 2018. This time span covers the development of the co-working phenomenon in Turkey in the past 20 years. It should also be noted that the number of branches indicates the results for the period when this research was conducted, thus excluding the potential effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Branch openings or closures are not included in the results. The CWSs examined in this research are listed below (table 1).

Table 1 List of CWSs included in the research with their key features

| CWS Name | Total Number of Locations in Istanbul | Year of Establishment | Interviewee | Investor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CWSS1 | 1 | 2016 | Co-founder | Private |

| CWSS2 | 3 | 2015 | Co-founder | Private |

| CWSS3 | 1 | 2016 | Co-founder | Private |

| CWSS4 | 11 | 2012 | Business Development Specialist | Private |

| CWSS5 | 1 | 2015 | Community & Makerlab Lead | Private |

| CWSS6 | 1 | 2017 | Space manager | Local Municipality |

| CWSS7 | 1 | 2015 | Co-founder | Private |

| CWSS8 | 1 | 2016 | Marketing and Business Development Manager | Private |

| CWSS9 | 2 | 2015 | Co-founder | Private |

| CWSS10 | 8 | 2006 | Community Manager | Private |

| CWSS11 | 2 | 2015 | Marketing Manager | Private |

| CWSS12 | 18 | 1999 | Area Manager | Private |

| CWSS13 | 6 | 2010 | Branch Manager | Private |

| CWSS14 | 1 | 2017 | Founder | Private |

| CWSS15 | 24 | 2010 | Customer Service Manager | Private |

| CWSS16 | 1 | 2018 | General Coordinator | Private |

| CWSS17 | 1 | 2018 | Branch Manager | Private |

| CWSS18 | 1 | 2016 | Co-founder | Private |

| CWSS19 | 1 | 2018 | Co-founder | Private |

| CWSS20 | 2 | 2018 | Co-founder | Private |

| 87 Locations |

3.3. Empirical Results

The empirical findings of the research are organized around two main topics and their sub-topics. The first group of findings regards the physical structure of the CWSs and the second group relates to the non-physical structure of these spaces.

3.3.1. Physical Structure

The questions in this part of the interview focused on three different aspects of the physical structure. The first group of physical structure questions was designed to determine the type of building in which the CWSs are housed. If many branches were available, each was evaluated separately with regard to the physical property.

The second group was designed to ascertain the layout and architectural features of the CWS. This group of questions was supported by on-site observation during the interviews.

The last group was designed to determine the facility management services and ancillary spaces that CWSs provide. These relate to the physical facilities that members can use through their membership.

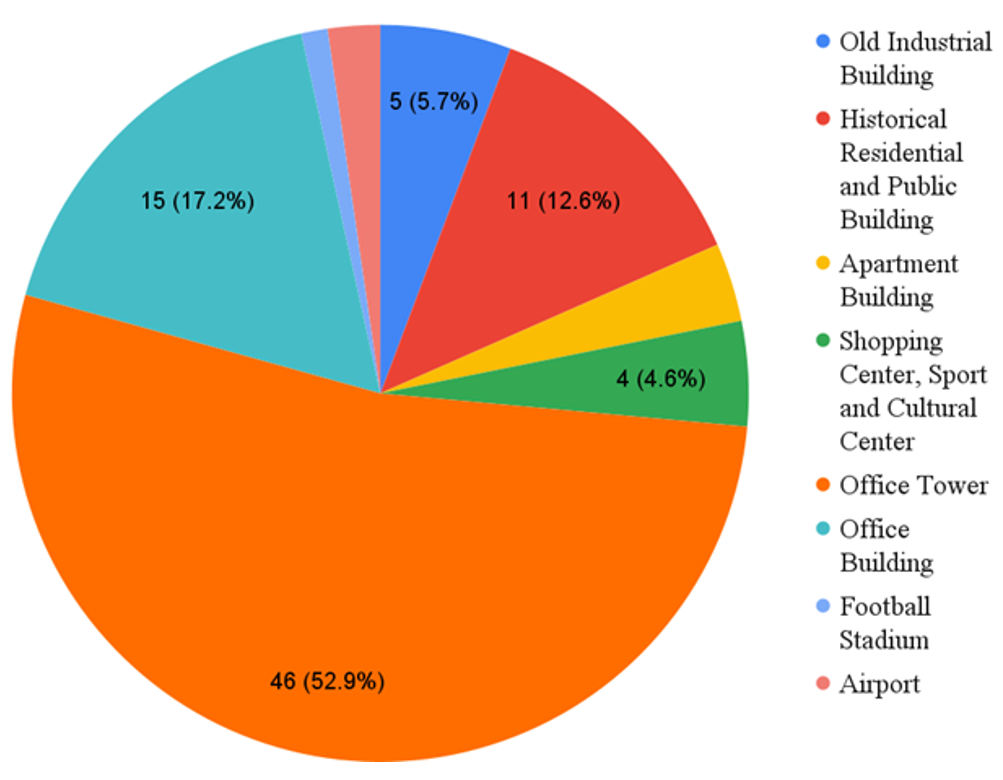

Type of Building

The first group of questions indicates that CWSs are located in office towers (high-rise office blocks) and office buildings (mid-rise office blocks), old industrial buildings and ateliers, football stadiums, airports, shopping centres, and apartment buildings in historical neighbourhoods or central areas. To provide comprehensible data, some buildings are presented in groups. Old industrial buildings include old printing houses, old textile ateliers, old textile warehouses, old beer factories, and old textile and carpentry ateliers. Historical residential and public buildings include old Istanbul mansions, historical residential apartment buildings, old Ottoman baths, and old restaurant complexes. Apartment buildings include apartment buildings in historical neighbourhoods and apartment buildings in the city. Shopping centres, sports and cultural centres include shopping centres, cultural, shopping, and office complexes, and a sports and life centre in a gated community. Despite the research sample consisting of 20 CWSs as enterprises, there are 87 locations in Istanbul. CWSs with many branches usually occupy office towers (high-rise office blocks). In this sense, 61 CWSs (70%) were located in office towers and office buildings (mid-rise office blocks) in the most accessible and prestigious locations of Istanbul's central areas. The results differ for CWSs without any other branches. Half of these CWSs are located in old industrial buildings, former ateliers or building complexes renovated for a new function. Figure 2 shows an overview of where CWSs and their branches are located.

Besides industrial buildings and ateliers, buildings that reflect characteristic Istanbul architecture are another location choice. While some CWSs locate most of their branches in office towers and buildings, they still tend to locate some branches in historical buildings or historical neighbourhoods. Although the number of CWSs in such buildings is a minority, they should be evaluated for their impact. The fact that CWSs with multiple locations choose to locate at least one of their branches in a historical building indicates the importance of these locations as an option. In this sense, 78% of the CWSs with multiple branches sampled in the research locate at least one of their branches in a historical building or old Istanbul mansion in a central area. In addition, CWSs tend to choose this location for target members. As one interviewee stated, co-founders may tailor their events, services, and the design of the space considering the location and the profile of the members in this location. The most striking results emerging from the interviews are that branches of some CWSs are located in airports and shopping centres. These are places on the periphery or in the city centre that did not serve as established office areas for mobile workers in the past.

Overall, the physical structure results based on the building type show that CWSs are located in various types of buildings. The top choice is office towers and office buildings in financial districts, along with renovated industrial buildings. Historical buildings in historical neighbourhoods are another prime choice. Moreover, locations such as airports, shopping centres or cultural complexes are a new type of office location that did not exist a decade ago.

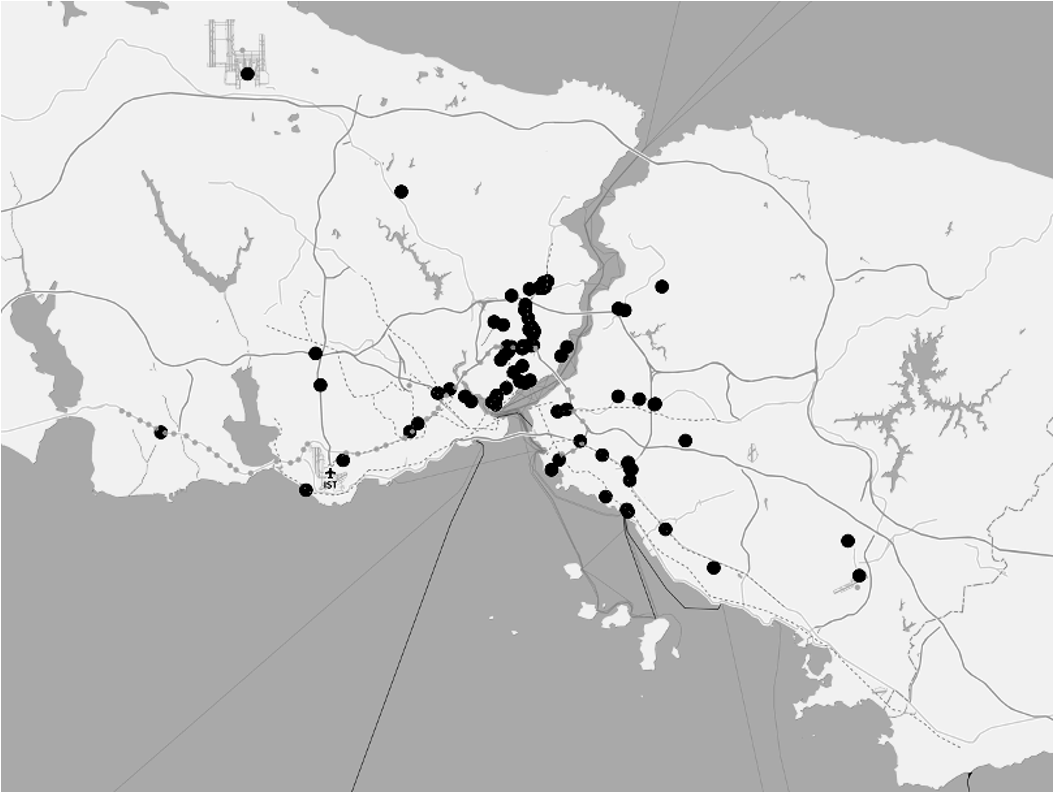

The top location for CWSs reveals the location pattern of CWSs in Istanbul. Office towers and office buildings in the most accessible area of Istanbul - in the heart of the Central Business District - hosts the most CWSs. The vast majority of CWSs are located in a triangle of strong metro connections to a broader area. Besides public transportation and commercial activities, this area is also attractive for cultural and creative activities. In addition, CWSs collect in the sub-centres on the European and Asian sides of the Bosphorus Strait around the arterial roads and connectors. The office areas around these arterial roads have the advantages of accessibility, service, and infrastructure such as parking, high speed Internet, security, etc. The coast of the city (Bosphorus, Golden Horn, and Marmara Sea) is especially a nest for single-unit CWSs. Interestingly, the oldest settlement of Istanbul (Historical Peninsula) does not have any CWSs. The spatial distribution of CWSs is shown on the figure below.

Layout and Architectural Features

The second group of physical structure questions concerned the layout and architectural features of CWSs. Results show that the layout and architectural features are directly associated with different membership options available in the spaces, because the design of the space determines the membership options. Most CWSs offer different types of memberships, such as flexible desk, fixed desk, serviced office, and meeting room. Table 2 presents the membership options available at the CWSs covered in the research.

Membership options determine the usage of the space. All participants reported that they provide open communal space or lounge areas for their members to work together. This finding confirms that co-working mainly occurs in large open areas in a shared environment. Membership options for these areas mainly cover hourly/daily use of the space, flexible desk, or fixed desk options. In addition to open office spaces, most participants (80%) also provide a serviced office option for their members. Membership options for closed office areas mainly relates to serviced offices in a reserved area. The companies using serviced offices are mainly micro enterprises. The average team size for the majority of the serviced office members are 3-4 people (50%) and 2-3 people (21%) For the other serviced office members, the average team size is 1-2 people and 4-5 people. More than 5 people in a serviced office area is rare in CWSs.

Meeting rooms are another important facility in CWSs. While they are mainly isolated spaces that can be used for meetings between members, they can also be rented for non-members of the community. Meeting rooms are mostly multipurpose rooms that can be used for workshops, events, seminars, etc. The vast majority of CWSs (95%) have a meeting room or event area that can be rented for other people or organizations besides its members. The profile of users of these rentable spaces is discussed in the community structure section.

A virtual office membership option has also emerged in recent years. CWSs offer this option for providing a business address with options such as mail handling and telephone assistance. Although it would seem that virtual offices have no physical assets in CWSs, this type of membership includes limited usage of meeting rooms or lounges. A majority of CWSs (60%) provide virtual offices as a membership option. The most surprising aspect of the data is in the reason for choosing this type of membership. The virtual office option creates a prestigious impact for its members. Virtual office members use the CWS address for their business cards. These places are located in central areas and the most prestigious office buildings in the city where a freelancer or a start-up generally cannot afford to rent a whole office flat. The virtual office membership option allows members to use this address for their business cards, which is advantageous for their business image.

Besides fixed desk, flexible desk, serviced office, and meeting room options, additional amenities (i.e., facility management services) are offered at CWSs. The most common amenity is a café-bistro. Other additional services are rare, but might include an exhibition area, music room, or design shop. The most striking result to emerge from the data is that one CWS has a crèche for their members to provide childcare while a member is working. A local municipality is the founder of this CWS.

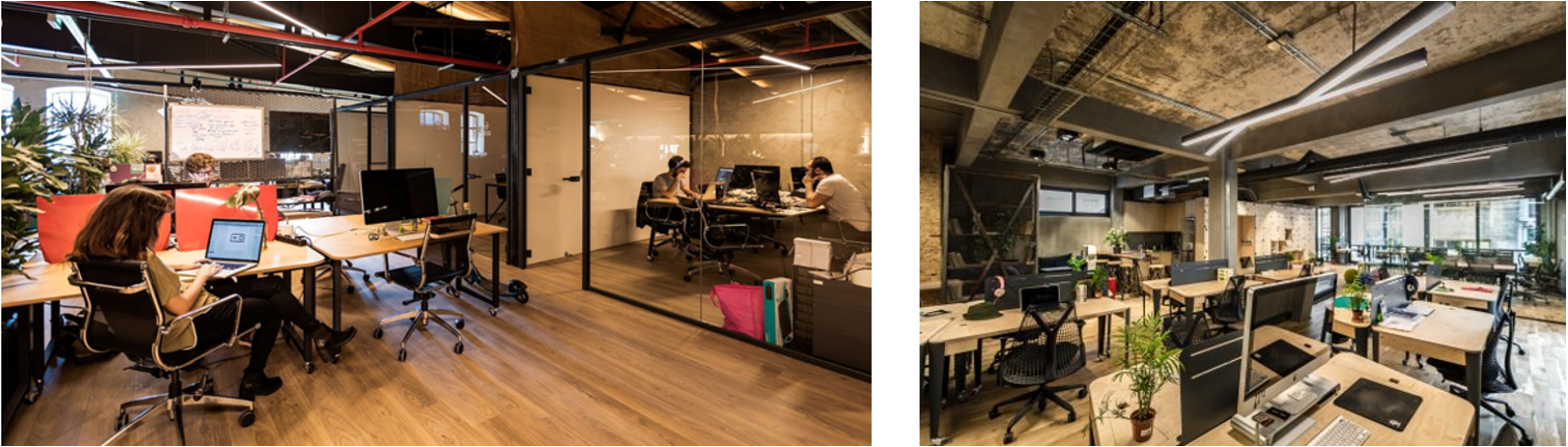

Design is a key element for CWSs. When asked if their CWS provided a place for nourishing new ideas and support creative processes, 88% of respondents who provided an answer to the question answered in the affirmative. The majority (67%) commented that they provide the required environment by specifically designing the space for it and creating an atmosphere for gathering and sharing ideas. On this issue, one interviewee said “Our design concept stimulates members to develop projects together. We try to create interactive spaces based on our design.” During the observations, it was also reported that designer furniture, technological equipment, designer objects, a relaxing environment, well-designed lounge areas, and large desks are striking feature of CWSs. It was also observed that work and leisure coincide depending on the design. Ample open spaces, open kitchens, and lounge areas within the working environment facilitate the co-existence of different activities such as working, relaxing, meeting, chatting, and enjoying. Another significant design concept was the use of high-ceilings, mezzanines, and open stairs, especially in renovated industrial buildings.

Table 2 Type of Memberships in CWSs

| Co-working | Serviced Office | Virtual Office | Event Space/ Meeting Room/ Workshop Space, etc. | Other | ||||

| Opening& Closing Times | Daily/ Hourly Use | Fixed Desk | Flexible Desk | |||||

| CWSS1 | 7/24 | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | Community Membership | |

| CWSS2 | 7/24 | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ||

| CWSS3 | 7/24 | ( | ( | ( | ( | |||

| CWSS4 | 8:00-20:00 | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | Café, Incubation Center |

| CWSS5 | 7/24 | ( | ( | ( | Makerspace/Prototyping Lab | |||

| CWSS6 | 8:00-00:00 | ( | ( | ( | Crèche (only for members), Bistro, Community Kitchen (work in progress) | |||

| CWSS7 | 8:00-20:00 | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | |

| CWSS8 | 9:00-21:00 | ( | ( | Café, Design Shop, Library | ||||

| CWSS9 | 7/24 | ( | ( | ( | ( | Exhibition Area, Music Room | ||

| CWSS10 | 7/24 | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | Disaster Recovery | |

| CWSS11 | 8:30-19:00 | ( | ( | ( | ( | |||

| CWSS12 | 7/24 | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | Disaster Recovery | |

| CWSS13 | 7/24 | ( | ( | ( | ( | |||

| CWSS14 | 9:00-20:00 Wknd11:00-19:00 | ( | ( | ( | ( | |||

| CWSS15 | 7/24 | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ||

| CWSS16 | 9:00-18:00 | ( | ( | ( | Art Gallery | |||

| CWSS17 | 7/24 | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | |

| CWSS18 | 7/24 | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | Music/Theatre stage | |

| CWSS19 | 7/24 | ( | ( | Architecture Library | ||||

| CWSS20 | 7/24 | ( | ( | ( | ( | ( | Lounge membership at all locations | |

Facility Management Services and Ancillary Spaces

The third group of physical structure questions was used to understand the facility management services and ancillary spaces provided in CWSs. Social facilities were excluded from these results, which focused only on physical facilities. Social services are discussed with respect to the non-physical structure.

On average, each CWS provides some basic facility management services such as high-speed Internet, printer, basic office furniture, coffee/tea during the day, snacks, meeting room access, locker, kitchenette, daily cleaning of rooms, desks and common areas, and security.

In addition to basic services, CWSs provide other optional services such as fixed phone lines, mail handling, answering services, and monthly magazines. It was observed that the basic facility management services and ancillary spaces are mainly the same in every type of CWS.

3.3.2 Non-physical Structure of CWSs

Financial Structure

CWSs are mostly established through private initiatives. There is a significant difference between the number of for-profit and non-profit CWSs: 19 out of 20 establishments are for-profit organizations. The central government and local municipalities play little role in establishing CWSs. At the time of the study, only one CWS founded by the local municipality was found in Istanbul. The main financial resources of for-profit CWSs are memberships, and meeting room/event space rentals. A minority of CWSs (15%) have a core team responsible for developing projects and educational programmes for their specification. Besides rental income, the core team members’ educational programmes and projects can be considered secondary income.

Community Structure

Number of Members

The number of CWS members varies from small communities to large networks. Table 3 shows an overview of the average number of members in these spaces.

Table 3 Number of members in CWSs

| CWS | Total Number of Locations | Average Number of Members at All CWS Locations |

|---|---|---|

| CW1 | 1 | 100-149 |

| CW2 | 3 | >500 |

| CW3 | 1 | 50-99 |

| CW4 | 11 | >500 |

| CW5 | 1 | 100-149 |

| CW6 | 1 | 1-49 |

| CW7 | 1 | 1-49 |

| CW8 | 1 | No Membership |

| CW9 | 2 | 1-49 |

| CW10 | 8 | >500 |

| CW11 | 2 | 50-100 |

| CW12 | 18 | >500 |

| CW13 | 6 | >500 |

| CW14 | 1 | 1-49 |

| CW15 | 24 | >500 |

| CW16 | 1 | 1-49 |

| CW17 | 1 | 1-49 |

| CW18 | 1 | 100-149 |

| CW19 | 1 | 50-99 |

| CW20 | 2 | 200-249 |

As expected, the table above shows a strong connection between the number of branches and number of members. CWSs with many branches mostly tend to have more than 500 members in total. There are more than 1000 members for CWSs with more than 10 branches. CWSs consisting of a single unit have small communities with less than 50 members. As the interviewees stated, serviced office members are counted as a single member, although there are mostly 3-4 people per team of serviced office members. A note of caution is necessary here since an average number of members per branch cannot be determined by dividing the total number of members by the number of branches, which would allow for a comparison with the result for single-unit CWSs. This is because each branch has a different size and consists of a different number of members.

Age Group

People who choose to work from CWSs are mostly in their late twenties and early thirties, also known as Generation Y. It was found that the interviewees do not tend to collect data related to age groups in their CWS. Thus, only half of the participants responded to this question and other participants only expressed their observations.

The results obtained from the interviews indicates that people between 16 and 20 years old do not choose to work in these spaces. The majority of members are between 26 and 30 years old, constituting 30% of members in the CWSs surveyed that provided data pertaining to age groups. Similarly, 25% of respondents are between 36-40 years old. Among the respondents, there are more members in age ranges 36-40 (22%) and 41-45 (7%) than in age group 21-25 (14%). Additionally, the participants who expressed their observations indicated that their members are flexible people younger than 40-45 years old. Similarly, another interviewee reported that the age of members ranges between 26-40, but the majority of are concentrated between the ages of 31 and 35. Members older than 45 years old are a minority (7%) among all age groups. Although some CWSs stated they do not keep statistical data on age groups, they still shared their observations. One participant reported that most of their members are aged 30-55. The interviewee’s explanation for this situation is that most of their members have their own companies or rent an additional space for employees. People with this profile are generally not at the beginning of their careers.

Gender

CWSs do not tend to keep statistical data about the gender of their members. Almost two-thirds of participants (75%) reported approximate data for gender. According to the results gathered from the interviews, men are slightly more involved in CWSs than women. Between 50% and 60% of members are men.

Member Profiles

Except for one CWS, all offer only membership-based options with a required minimum of at least 1-month membership. Besides the financial benefits, one explanation for this is that it is aimed to build a community with steady members, which is a desirable issue for CWSs. During the interviews, most CWS managers commented that they purposely organize events and design the space for possible interaction to build community and a more sociable place. CWS membership options have an impact on the profiles of members. CWSs with only hourly/daily desks, hot desks, or meeting rooms determine a different profile than CWSs with serviced offices or minimum 1-month memberships. One participant with only a daily/hourly use option stated that their visitors are mostly software developers, designers, and start-up entrepreneurs who do not yet have an office but need a place to work. The participant also stated that foreign visitors make up half of all visitors.

Membership-based CWSs are multi-disciplinary places. While CWS members are mostly freelancers, entrepreneurs, and creative individuals, as one interviewee reported, serviced office members are mostly micro enterprises and creative departments from corporate firms. Whether in CWSs or serviced offices, people who choose to work from CWSs mostly operate in creative sectors. The data gathered from the questionnaire show that software development is the most common profession in CWSs. When calculating the average of the professions from the questionnaire, software development corresponds to 13.7% of all professions in CWSs. From the same perspective, consulting services (12.6%), advertising (12.6%), web design (11.6%), IT services (9.5%), social media services (9.5%), digital services (8.9%), architecture (7.4%), marketing (7.4%), and graphic design (6.8%) are other professions in CWSs.

The most obvious finding to emerge from the analysis is that CWSs mainly host individuals and companies from the creative economy. To understand the sectors in CWSs, all members, including virtual office and serviced office members, are included in the sample. However, CWSs with only hourly or daily use options (only 1 CWS) was excluded from the sample.

Partnership Structure

The partnership structure of CWSs is addressed through two aspects. First, partnerships during the establishment process were investigated. Second, current partnership projects that developed during the establishment process were addressed.

CWSs are overwhelmingly private enterprises (95%). Only one CWS was founded by a local municipality in Istanbul. In addition, it is reported that only two of the CWSs relied on support such as public funding or international network resources during the establishment process. Although there is support, it consists of just a small part of the establishment investment.

The majority of partnerships in CWSs occur during event organization. CWS managers consider educational programmes, workshops, and events as project-based partnerships. The role of CWSs is mainly to provide a space for these types of partnerships. Whether the event is paid or free, the benefits of these partnerships for CWSs lie in creating a learning environment for members, supporting different groups and ideas, and - most importantly - reaching more people.

Besides events, discounted prices for some groups or free use of the space are other types of partnerships. In this context, CWSs institute partnerships with NGO’s, universities, professional organizations, platforms, technoparks, incubation centres, and special groups such as makers or artists.

Communication Structure

Methods of communication are a significant issue for CWSs. Communication issues were therefore investigated in two ways. The first aims to understand communication within CWSs while the second reveals the communication methods CWSs use to express themselves.

As observed during site visits and from remarks made by the interviewees, CWS design features interaction and communication. The main communication method in CWSs is face-to-face communication. The managers report that even they use other additional methods to support face-to-face communication and help members interact with each other by helping them find the necessary person or idea, either within the community or outside.

Other than face-to-face communication, the managers also rely on technology for communication. Among the CWSs responding to the question about the communication methods used within the CWS (90%), 70% stated that they use digital tools such as Slack, WhatsApp, Facebook groups, Telegram, an interface, or other apps to communicate with each other within the hub. Similarly, 35% of CWSs use email groups for communication. One co-working manager also pointed out that they have an online pool which CWS members can use to reach other people on the network.

The next section of questions about the communication structure concerned the methods used by CWSs to express themselves and reach wider communities. CWSs mainly use the power of social media to inform other people about their events, daily lifestyle, and opportunities. Each CWS has at least one social media account such as Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, or LinkedIn. Moreover, 50% of CWSs have a blog where they regularly share content such as updates, news, motivational articles, etc. Organizing events is the most potent tool for CWSs to attract more people. CWSs organize or host events for members and non-members to establish a social environment that provides opportunities for networking and knowledge transfer. It also allows non-members to experience the environment, leading them to share the experience with other people. CWSs generally tend to collect contact information from non-members during events, which generates an opportunity to email them about upcoming events and updates.

Decision-Making Structure

At CWSs, management boards mostly make decisions. Among CWSs with a management board (85%), all have a co-founder of the CWS on the board except for one instance. This exception is the Istanbul link in a global chain (Regus) whose management board is located in another country. Management boards have characteristic differences depending on their establishment structure. The management board of the CWS founded by the municipality consists of managers from the municipality who also act as an advisory committee. The management boards of private CWSs consist of co-founders and in some cases investors, and the boards are mainly small. While 82% of spaces have five or fewer people on their management boards, only 18% of CWSs have more than five people. CWSs with many branches around the city have branch managers who generally report to management boards. CWSs without any management board are mostly spaces without any other branches.

Only a minority of CWSs include their members in the decision-making process (21%) by using specific tools. Among these examples, one has a management board but has developed tools for members to participate in the decision-making process, for example, by being encouraged to take responsibility for the organization and management of some events. In other cases, the managers create a sharing environment via regular community meetings where members can share their ideas, comments, and feedback, and the community can take action as a result. The managers act as facilitators in this process. Although the decisions are intended to be made by community members, the community is not included in decisions such as selecting newcomers or financial issues.

Although most CWSs make decisions via their management boards, there is no hierarchical order between members and managers. CWSs are mostly transparent spaces. A majority of CWS managers or co-founders have no separate closed office and work alongside other members. This affects the relationship between members and managers. As most managers pointed out during the interviews, the members can easily reach the managers and make requests quickly. Besides small talk during the day, the managers use systematic tools for collecting members’ ideas such as regular surveys. When asked whether they allow members to participate in the decision-making process, even if the answer was no, the participants were unanimous in the view that they receive opinions from the community and consider their ideas before making decisions about the CWS.

Organization and Management

With regard to the research results on CWS community structure, it was found that CWS members are predominantly SMEs (see the community structure results). When the organization and management structure of CWSs is examined, it also shows that the CWSs are themselves SMEs. The findings show that the organization and management structure of these spaces can be assigned to one of two categories. The first is a location/branch-based organization and management structure and the second is a department/position-based organization and management structure.

According to the findings, the location-based organization and management structure, as expected, consists of a branch manager and guest relations contact/receptionist. Branch managers are mainly affiliated with upper levels of management and generally report to them. CWSs with branches are based in this type of organization and management structure. The above-mentioned upper levels are referred to the positions such as CEO, CFO, co-founder, community manager, marketing manager, and business development manager. Branch managers are responsible for communicating with branch members, collecting feedback from the community, and implementing the actions chosen by upper levels.

The department/position-based organization and management structure is observed in CWSs without any branches. In these smaller organizations, co-founders mostly perform several roles. They make all the operational and managerial decisions while sometimes getting help from external units such as accounting. CWSs with more than one co-founder mostly define their responsibilities according to their professional backgrounds. For instance, while some co-founders take responsibility for content development or membership relations, others may take responsibility for financial or operational aspects.

Results

The findings from this study reveal that CWSs have different characteristics and cannot be categorized as one type. However, this does not mean that these spaces lack common features. On the whole, basic facility management services and ancillary spaces offered by CWSs are practically the same. Likewise, the financial structure and partnership structure are not distinctive features of CWSs. Nevertheless, types differ along other topics: type of building, community structure, communication structure, decision-making structure, and organization and management structure. The results of the study suggest that there are four different types of co-working spaces in Istanbul.

Type 1: Chain CWSs

These CWSs (figure 4) are branch-based organizations of local or global brands. They are service oriented and mostly provide the same service quality in all locations. They are private enterprises and have no establishment investments from public funds. They are mostly located in business centres in prestigious buildings in accessible areas of the city. This type of CWS hosts creative workers and a wide range of professionals such as lawyers, private tutors, dieticians, etc. Although they send regular surveys to members to collect their requests, members are not included in the decision-making process. Instead of regular member events such as talks or entrepreneurship events, they mostly organize hobby events for members if there is a demand. They have branch-based organization and management structures. There are seven chain CWSs in Istanbul of this type and only two are global brands. They cover 71 locations in Istanbul and some have other branches in other large cities in Turkey.

Type 2: Lifestyle CWSs

These CWSs have a remarkable design concept with well-designed furniture and objects. They are local initiatives with strong global connections located in renovated industrial buildings/ateliers or large spaces in accessible locations. They both may be branch-based or single units. Although their virtual office service encompasses a wide range of professions, members mostly consist of creative individuals. Creative departments of big corporate companies also tend to locate some of their departments in these spaces. Special events for members are a considerable part of the daily routine in these spaces. They frequently host many events for wider audiences which provides them with an event space image with many possibilities for social connections. Although the inclusion of members in the decision-making process is low, face-to-face communication with the managers allows members to express their requests and suggestions without any hierarchical order. This type of CWS refers to private initiatives and has no establishment investment from public funds. Their organization and management structure are position based. There are two CWSs of this type (figure 5) covering a total of five locations in Istanbul.

Type 3: Community-oriented CWSs

These are small local communities in single units without other branches around the city. Their main focus is on building a community around the space rather than providing services. These spaces are small communities considering the number of members (less than 50), most of whom are creative workers looking for community spirit. Although the members have no say in the selection of new members, the managers have a selective membership process to generate an effective community. For this reason, the managers make an effort to build a community considering a balance between genders, professions, and number of members. The co-founders of those spaces are also part of the community and tend to include members in the decision-making process. Events are part of the daily routine and a catalyst for strong community relations. Local or international events, talks, and workshops are organized frequently in community-oriented CWSs. Public funds may be part of the establishment investment in these spaces. Their organization and management structure is position based. There are four community-based CWSs in Istanbul as determined by this research, with a total of four locations (figure 6).

Source: https://www.atolye.io/news/covid-19-update/

Figure 6 Examples of Type 3: Community oriented CWSs

Type 4: Service-oriented CWSs

This type of CWS (figure 7) is similar to the chain CWSs. The most significant difference with respect to service-oriented CWSs, however, is their single-unit structure without other branches around the city. They focus on providing an appropriate physical service for their members rather than building a community around a single unit. They are private enterprises and mostly located in standard office towers or buildings in accessible areas of the city. Events are not the main focus of this type of space. Interaction between members emerges spontaneously in designated common areas. Organizations and events for community building are not the managers’ main focus. Although members are not included in the decision-making process in service-oriented CWSs, they do reap the benefits of being part of a small community by being able to contact the managers directly. There are seven service-oriented CWSs in Istanbul with seven different locations.

Source: Image on the left: https://www.workhaus.com.tr/#hazirofis, image on the right: https://daire.co/daire-coworking-en/

Figure 7 Examples of Type 4: Service oriented CWSs

CWSs in Istanbul are mostly Type 1: Chain and Type 4: Service-Oriented, covering a total of 78 locations in Istanbul. The results (table 4) reveal that the main idea behind establishing a CWS is to provide an infrastructure for individuals and SMEs. Although the number of community-oriented CWSs is scarce, further research on their impact should be done.

Table 4 Types of CWSs in Istanbul based on both physical and non-physical structures

| Type 1 Chain | Type 2 Lifestyle | Type 3 Community Oriented | Type 4 Service | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of building | -Office Towers and Office Buildings -Multibranch | -Renovated industrial buildings/ateliers and office towers -Multibranch and single unit | -Renovated buildings -Single unit without any branch | -Office Towers, Office Buildings, Old Industrial Buildings, Historical buildings -Single unit without any branch |

| Layout and architectural features | Service oriented and mostly the same service quality in all locations | Remarkable design concept with well-designed furniture and objects | -Remarkable design | A qualified physical service |

| Facility management services | Basic CWS services | Basic CWS services | Basic CWS services + makerspaces + café + kindergarten | Basic CWS services |

| Financial structure | Private Initiatives-For-profit organization | Private Initiatives-For-profit organization | Private and public Initiatives-For-profit organization | Private Initiatives-For-profit organization |

| Community structure | Creative workers and a wide range of professionals such as lawyers, private tutors, dieticians, etc. | Creative individuals and creative departments of big corporate companies | -Creative workers looking for community spirit -Less than 50 members - Balance between genders, professions, and number of members | -Mostly Creative individuals and companies -Less than 100 members |

| Partnership structure | Partnership during establishment: private investment Current Partnership Projects: event-based partnerships for hobby events | Partnership during establishment: private investment Current Partnership Projects: event-based partnerships for talks, gatherings | Partnership during establishment: private investment and support from public funds Current Partnership Projects: Local or international events, talks and workshops | Partnership during establishment: private investment Current Partnership Projects: not focus on events and talks |

| Communication structure | Communication within CWS: Communication with Public: website, social media channels | Communication within CWS: Communication with Public: events, blogs, websites, social media channels | Communication within CWS: Communication with Public: events, blogs, websites, social media channels | Communication within CWS: Communication with Public: website, social media channels |

| Decision-making structure | No involvement of members | No involvement of members but face-to-face communication with managers | Involvement of members | No involvement of members |

| Organization and management structure | Branch based | Position based | Position based | Position based |

Conclusion

The existence of different types of CWSs suggests that some distinctive features of CWSs differentiate these spaces. One significant finding emerging from this study is that different types relate to differences concerning the following structures: communication, decision-making, and organization and management. Nevertheless, the differences in these structures do not mean that the physical structure, financial structure, community structure, and partnership structure are irrelevant in differentiating CWSs. In fact, the approach to communication, decision-making, and organization and management directly affect the physical structure, financial structure, community structure and partnership structure of CWSs. From the data gathered from the founders’/managers’ perspective, the insights gained from this study may be useful for developing policies to implement different types of CWSs at different locations in the city. However, further studies related to the members’ perspectives are necessary to reveal their motivation for choosing a given CWS for work. One issue that was not addressed in the study was whether the COVID-19 pandemic led to the emergence of novel types of CWSs. Since the interviews were conducted before the pandemic, the effect of COVID-19 on CWSs was not investigated. The extent to which COVID-19 affected different types of CWSs would hence be an interesting question for investigation. Therefore, further studies regarding the role of COVID-19 on the emergence of CWS would be worthwhile.