Commute 1. travel some distance between one's home and place of work on a regular basis. 2. reduce (a judicial sentence, especially a sentence of death) to another less severe one. 3. change one thing into another. 4. In mathematics (of two operations or quantities) have a commutative relation. Cambridge Dictionary

Historically, we see changes in the social structures of first world countries as a result of, or in the context of, women’s emancipation. However, both these changes, and the continuation (or increase) of a gender gap, are unfolding in the firmly formed physical environment, the inadequacies of which are becoming ever more apparent. These can be largely attributed to the inert nature of our physical environment and to its form being originally shaped by men. If we observe specific ways in which the physical environment defines a woman’s life, we can discuss the position and the condition of ‘women in architecture’. On the other hand, we can take into account the role of a female professional who participates in the creation of the physical environment, and consequently focus on the role of ‘women in architecture’.

Why this may be of interest relates to the understanding of physical space by those who participate in it both as end users and as creators. This essay is concerned with the causal relationship of women’s condition and her abilities within the built environment, or more precisely with the emancipation of a woman in the context of her immediate dependence on the built environment, as well as her role in defining and creating that environment.

The progression of women in education and the workforce are predominantly occurring in addition to their roles of caretakers and homemakers. Women find themselves engaged in the abiding negotiations: career vs home, often emotionally and professionally conflicting. Therefore, some of the questions arising here consider compromises which women make in terms of choosing their workplace relative to the commute distance and their family roles or the effect which their concerns about safety in public have on their modes of transport. However, the main focus is on the everyday territorial rights of women, and the subconscious, or inherent, interpretation of the right to space.

David Harvey1 states that the most important fact about industrial capitalism is that it forced a separation between the place of work and the place of reproduction and consumption. This is, of course, just a spatial consequence of the historic observation of a man’s role as a ‘producer’ or a wage earner, whilst the woman remains associated with consumption and non-earning labour at home. To access the place of work, a woman had to find her way out of the patriarchal frameworks which historically forbade her from obtaining education, through overcoming legal, as well as physical, obstacles.

Although the definition of a woman is not equivalent to that of a mother, it has to be noted that her position has, throughout the history, been determined by her corporeal ability: childbearing. Further to this, and perceived as a natural progression, the role of a ‘carer’ is still primarily associated with women. These archetypal perceptions, deeply ingrained in our subconscious and present in our conscious behaviours and attitudes, may be the consequence of the alliance of biological abilities and traditional patriarchal arrangements, but their effects are particularly significant for the firmly established circular system, where economic, social and cultural progression of women is conditioned by their biological power. Although often recognised in the workplace setting, some of the issues related to female progression are identifiable in the spatial settings they occupy and navigate, and the morphology of, in equal parts but different ways, the urban and rural environments.

Bluntly put: in physical terms, on corporeal as well as geographical level, the woman’s ability qualifies her disability.

Griselda Pollock2 quoted Jules Simon, a French republican politician writing from 1892: “…what is man’s vocation? It is to be a good citizen. And woman’s? To be a good wife and a good mother. One is in some way called to the outside world, the other is retained for the interior”. Pollock noted that with the building of suburbs, the separation between home and work became formalised on an urban scale, and spatially, women’s and men’s distinct geographical domains were marked.

The mock-pastoral qualities of a house with a front lawn in the suburbs are the aesthetics not only related to the middle class and their economic status, but primarily to the psychology of peaceful living. A refuge to which a wage-earning man can return to after a hectic day in the city, suburbs can equally be observed as an asylum from which the woman can hardly escape. Leslie Kern argues that suburbs may not be consciously keeping the woman out of the workplace, but taking into account the isolation, need for multiple vehicles and demands of household managing and childcare, suburbs push women either out of the workforce or into lower paying jobs, which allow them to manage the demands of suburban family life3. It is important to note here that the issue points to the structure, both physical and organisational, of the suburbs, rather than their existence. If we observe suburbs as a natural expansion of cities, especially as a welcome increase of their residential capacities, what becomes immediately obvious is the problem of zoning, possibly linked to the investment aptitude and yield in the capitalist economies. Gerda Wekerle4 argued that a woman’s place is in the city, where density allows for distances between home, work and childcare to be manageable on foot or by means of regular public transport. However, the issue of mobility is actually related to the provision of services and facilities within reach, and not only limited to running the household and caring for family members, but furthermore, those related to women’s professional, cultural and educational needs. Additionally, the urban densities in question, provide variety of other services and amenities which allow for more efficient management of errands, but also foster social relationships, particularly within groups of women.

Movement

The experience of the ‘freedom of the city’, and the subsequent loss of same, differs for urban, suburban dwellers and those in wider commuter belts. Access to essential services, starting from health care and ranging as wide as economic, social, educational, cultural and of course - including access to workforce, is dependent on transportation options. The Inland Transport Committee’s report to the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe 20095 recognised that the transport is traditionally a male dominated sector, bothfrom the employment point of view and for the values which are embedded. At same time, it is widely recognised that gender sensitive issues (in the transport domain) are many and highly relevant. Gender differences in travel behaviour are evident, with women reducing their commute significantly after having children, which in turn reduces their choices of workplaces, usually with detrimental consequences for women’s careers. There are other patterns which differentiate women’s movement - concerning safety, from crime which affects men as well, but also harassment, rape and molestation which tend to be directed almost exclusively at women. Various studies, surveys and reports6 carried out by departments or institutes of transport as well as those related to gender equality, globally, show the repetitive patterns of women’s travel behaviours in developed countries - women’s daily activities are more complex than those of men and, in addition to work related commute, often include provision of domestic services and care for dependents. As a result, women’s commuting distances are shorter, but the duration of their commute is longer as it includes numerous stop-overs.

Public transportation can pose a significant challenge to women: from access to it, in terms of the distance from home/office which affects temporal concerns, through cost of transportation especially when it includes for journey interruptions to accommodate drop-offs and similar, to safety on the way to, from and within public transport; through smaller but equally impeding details which refer to the design of the public transport access points (whether the metro/train/bus station has a fully operational lift/escalator; provision of lights and surveillance etc.).

At the same time, the above mentioned UN ECE Report 20095 illustrates stark contrast in car ownership- from Kenya where 24% of male use a car compared to only 9% of female heads of households, with similar numbers in Brazil, to Northern Ireland where 79% of men hold a driver’s license compared to 61% of women, which again illustrates not only gender disadvantages in daily circulation but more importantly the contemporary economic condition of women globally, as car ownership is still associated with the economic and social status, and certainly contributes to the economic independence. In addition to this, observing the structures of cities and more importantly rural communities’ services provision, we can identify that expanding residential areas in both suburban and rural environments contribute to more complex demands for accessing (essential) services, and are further identifiable throughout the hierarchy of services and spaces (work, social, culture). Furthermore, this means that in addition to complexity of journeys which, as we have seen, tend to be exacerbated for designated ‘carers’ in the family, a role still dominantly held by women, the choice of transportation means is reduced, with the cost increasing especially for public transport where frequent needs for stop-overs and changes are usually not recognised by fare provisions.

The European Institute for Gender Equality study7 shows that less than 10% of the workforce in the transportation industry are women, and this is mainly data collected in ex-socialist countries which traditionally show less gender bias in the workplace. Contemporary transportation studies openly conclude that more women need to be employed in the sector if changes in sector are to be observed.

Particularly interesting here is the question of the changes, and the expectation of their proposals and implementations based on the recognition of the needs of women by female professionals brought to the specific field.

Christine Murray8 is not the only one who wondered if mothers would design cities differently, after experiencing the city as a mother of three. This poses an important question: is it a gender bias in the profession or the life experience and compassion that we expect from the creators of our physical environment? The inappropriateness of the stereotypical view that women are more compassionate, thus would be better ‘designers for all’, can only be supported by the outdated and shockingly misogynistic analysis of a woman by Schopenhauer (On Women, essay).

However, recent surveys show that 75% of women in architecture don’t have children, furthermore, about half of women architects are less than 30 years old, with only 2% practitioners being over the age of 619. Compared to participation in the professional field of transportation, female architects are better represented, but how much difference does their presence make, and can it be identified, in the physical environment?

Leslie Kern’s experience as a mother, comparing the attitude of people on her journeys and her mobility through the city to her pre-motherhood days: “This level of rudeness didn’t happen every day, but underlying all of this social hostility was the fact that the city itself, its very form and function, was set up to make my life shockingly difficult. I was accustomed to being aware of my environment in terms of safety, which had a lot more to do with who was in the environment, rather than the environment itself. Now, however, the city was out to get me. Barriers that my able-bodied, youthful self, had never encountered were suddenly slamming into me at every turn. The freedom that the city had once represented seemed like a distant memory.” 10

Returning to the city, once it is accessed, what is really on offer?

An incident study of the Women’s Library in London as one of the few purpose-built, or more importantly- refurbished, public buildings, is also an important study of a building re-designed by a woman for women. The Wash House from 1846, is the original building converted in 1995 by Claire Wright, an architect from London based practice Wright& Wright, who believed that the firm won the commission because of ‘their willingness to conserve a place of women’s work’. To Annemarie Adam’s11 question about what sort of architecture might be inspired by texts about the history of women, Claire responds with a smile: “It's all in the number of loos [washrooms]”. And although refreshingly honest in recognition of women’s physiological needs, the design fails to acknowledge, from a twenty-first century perspective, that perhaps one of the historic building’s most important attributes is that the wash house included day-care facilities, allowing women to focus on work - washing, drying, and ironing, while their children were being cared for. A nineteenth century provision which allowed for more efficient labour - the childcare, which also seems accidental on inspection of layout drawings, failed to translate into the twenty first century dedicated facility: over one hundred and fifty years of emancipation still does not recognise that mothers, too, are women in education, no more than part of the work force, as well as the fact that the women who are excluded from education are often victims of the lack of, or the inadequacy of, the support services provided.

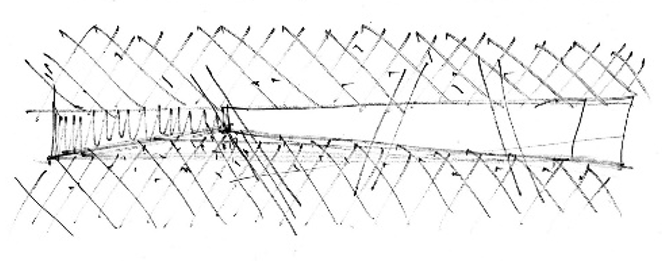

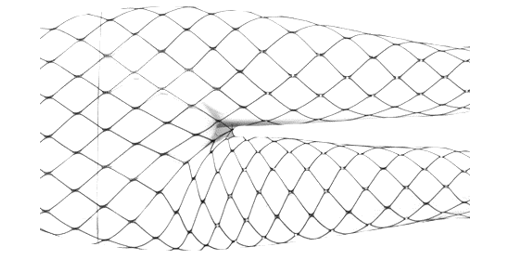

In another example of a building dedicated to female education, dominantly although not exclusively engaging female students, the Ewha University of Women Studies (Seoul, 2008) we observe the patriarchal attitude conveyed through spatial means. The sunken university building provides relief to the heavily urban area where it is located, but it is hard not to link the decision to ‘bury’, hide and impose discreet presence of the university premises to the historical position and perception of women and associated prevailing culture. If Adam’s analysis of the Women’s Library highlighted that “the library's feminist stance is at least five-fold, legible in its connection to the site, its deference to history, the absence of spatial hierarchies, its environmental stance, and perhaps most importantly, its relationship to contemporary architecture in London”12, we might observe that the Ewha University building is a nod to absence, withdrawal and silence. This lack of ambition to be present, never mind compete with the surroundings, or claim it’s right to territory, can possibly be linked to Dominic Perrault’s initial concept - a sketch - which covertly invokes the persistent idea of femininity - through anatomy and the focus on the intimate (Figures 1 and 2)

Towards the private

Esra Akcan13 analysed the translation process of the architectural and cultural values in modernist Turkey through, amongst many other examples, the Makbule Atadan House (Ankara, 1935-36) designed by Seyfi Arkan, an architect who trained with Hans Poelzig. Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s14 mission was to modernise Turkey, and he commissioned Clemens Holzmeister to design his own residence, with the intention to abandon Ottoman traditions and embrace the western values. It is significant to note that Holzmeister’s proposal was chosen over another, by an office from Berlin, which included a harem in the design - conveying that the new republic was firmly abandoning segregation of women. Kemal did not interfere with Holzmeister’s development of the design of his own residence, so it is possible that the Atadan house was developed within similar circumstances: it was designed as a glass house, where open plan and transparency represent the modern Turkish woman, and furthermore- modernised society. But the house has been designed with no input from Kemal’s sister, Makbule Atadan, who later stated that as a response to her complaint that she is not allowed education, her brother gifted her two houses and asked if she needed money. Enveloped in perceived transparency, consequently called ‘camli kӧșk’ (glass villa), the house screened off the private areas, including the ‘women’s room’, a curiously designated space in a house owned by a woman. To announce progress and demonstrate societal change, Makbule Atadan was perhaps exhibited, rather than accommodated, and left to adjust her living requirements to the provisions of the given space.

“Women never have a half-hour in all their lives (excepting before or after anybody is up in the house) that they can call their own, without fear of offending or of hurting someone. Why do people sit up so late, or, more rarely, get up so early? Not because the day is not long enough, but because they have 'no time in the day to themselves.” Florence Nightingale, 1852

At the same time as development of the Makbule Atadan House, the early twentieth century in Germany saw a redefinition of the residential space, and much consideration was given to women in the household through theoretical work alongside applied design. Although optimising women’s time and management of the household, the changes were instigated primarily to alleviate the issue of sourcing house-help, to economise and standardise production and, which is of great significance, to reduce the size of the habitable unit in the post-war world. The kitchen was the focus of these studies, all of which seemed to unquestionably consider only female labour within a domestic kitchen. Moreover, considerations would always revolve around the woman in the household, and consider the needs of a family with the woman as the main carer and manager of the household, referring to a possibility of the greater number of women joining the workforce as a potential to flood the labour market with cheap female labour15. If economic factors are taken into consideration, most of the new models (of residential space as well as equipment and appliances) were out of reach for most but the middle class, posing a question of whether the changes were brought to improve living conditions and emancipate women of working- and lower-class families, as it is often perceived, or to eradicate intimate female spaces from residential settings and fully engage women in servicing the family. In the case of cultures where progress would have been signified through incorporation of women into the life of the house (Atadan House), the boundary between public and private female, even in the woman’s own home, was gently obscured through use of contemporary aesthetics, rather than formal change.

The ‘scientific management’ of the home16, as it developed and spread throughout the western world at the beginning of the twentieth century, found support amongst women and feminists as well. Harrington Emmerson, in the foreword of Frederick’s book, argued that the woman’s role and task was far more complex than that of a man in the workforce, and acknowledged woman’s contribution to the order of the world and even credited her as a creator of civilisation. However, Emmerson failed to note that for all her success at home, that same woman relied on the husband and his income, and was forever dependant. Whether Christine Frederick recognised the strong traditional values in the society and took small steps towards liberating women through optimising their time within the household, rather than forcing them to the workplace, or whether she just used the opportunity to develop her own career - the message conveyed through her work, as well as her contemporaries in the same domain, riveted women to the domestic, spatially reduced, settings and defined the contemporary woman as a master of household appliances, assigning her a profession - that of the unpaid caretaker.

On the other hand, the Rietveld Schrӧder House (Utrecht, 1924) is still primarily recognised for its aesthetic qualities. Designed by Gerrit Rietveld, Dutch designer and architect, but to the clear direction of Truus Schrӧder -Schrӓder’s brief, the house is an ode to a conscious, independent woman’s space, marrying her work requirements to her dedication as a widowed mother of three. For Truus, an amateur designer, the house had to be a place of work, as well as a caring home. A woman, who despite being widowed maintained and satisfied her emotional needs, created a house as a profoundly redefined dwelling: modest in scale and means, daring in spatial gestures and aesthetic values the house can still be understood as a representative of changed times: its flexibility, adaptability and ability, reflect the spirit of the woman who conceived it.

Interestingly, the Rietveld Schrӧder House, when observed as a woman’s house, is criticised for the lack of segregation of work and living arrangements17. Perhaps, the issue here lies in the opportunities available for ‘work from home’ in terms of suitable professional fields and career progression. Today, in a post-pandemic world, it is easier to recognise the value of suitable space(s) available within the residential dwelling which, even simply by reduction of commute time, contribute to the quality of life in general.

Another example of early twentieth century female-led designs is Maison de Verre by Pierre Chareau (Paris, 1928-1932). The client’s, Madame Dalsace’s, input ensured that the house - while still a working premise for her husband, Doctor Dalsace - contains intimate and clearly distinguished male and female domains. Gradually transitioning from public (doctor’s surgery, living room and drawing room) to intimate (her boudoir and husband’s study) spaces, the lower levels of a three-storey house built into an existing building, belong to the couple’s human and public roles18. The top floor contains their intimate space, master bedroom, and carefully manufactured bathrooms- spaces which unify deliberate individuals. If the house, not unlike the human body in medicine, is seen as a machine, and if the woman’s place is within that house, Maison de Verre certainly radicalises the role and territorial rights of a housewife. Of course, strongly reflecting bourgeoisie notions and made possible by the economic capacity of this particular household, the glass house solidifies the position of the woman as an equal to a man through allocation of spaces and their character - both programmatic and aesthetic. The design maintains her fragility and contrasts it to the cold mechanics of the wage-earning.

Inadequate exchange

Are there female spaces, or spaces which facilitate women, which we can identify in the contemporary built environment? Furthermore, what distinguishes these spaces and do they all belong to the same typology? What can balance the outcome of the inadequate exchange: boudoir for an open plan kitchen and living space? And are female architects better positioned to recognise women’s needs and establish adequate structures to support them? Finally, where do the paths of women in architecture and female architects intersect?

“From the beginning, the suburb was coded feminine” states Davison19 in reference to the Evangelist dualisms of the nineteenth century - God and Satan, man and woman, The Christian (who escapes to the suburbs) and the World (that of the sinful city). Although the expansion of suburbs became possible with the developments of road and rail networks, and their necessity, an evident result of the industrialisation at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, but which became prominent in the post-World War II period, their realm of domesticity continued to imply that the suburb is the place which belongs to the same woman that Evangelists defined a century before - a patient maid who awaits her knight. Two centuries later, is it still possible to agree with Leslie Kern’s point of view that suburbs are not consciously entrapping women, if their history clearly evidences that this is what they have been designed to do, albeit with a noble intention of removing the family from the vices of the dense urban environments?

Besides the lack of services and content within the suburbs - particularly related to education and career opportunities, the infrastructure which provides access to these is inadequate in terms of specific needs which are defined by gender. Identification of these issues by the European study of Gender in Transport points to the lack of female professionals within the transportation industry, implying that the presence of women in the profession would resolve the problem of commute, for women.

The assumption that a female professional in itself represents the resolution of gender issues within the built environment neglects the complexity and shifts the responsibility from the collective to an individual, whose experience, mission and compassion is prejudiced.

When Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, proclaimed “I am not a kitchen”20 at the age of 101 she renounced her contribution to the gender equality progress which stemmed from her recognition of the economic independence and self-realisation of women being an important common good. The way she saw the “new woman” of the post-World War I period was not the result of her experience, but rather her response to patriarchal traditions from a position of someone who had been a part of that environment. Similarly, the Women’s Library in London, some sixty years later, was designed by a woman who defined the gender profile of space through pursuit of its hierarchical qualities and the provision of sanitary facilities, neglecting to provide the childcare facilities for both users and employees within the library, which existed in that same building when it was used as a washroom, more than a century prior to its refurbishment. This may evidence that support for mothers in workplace, albeit incidental and unregulated, existed historically for low paid workers, whereas in contemporary space which caters primarily for educated women, this provision is neglected. Dominic Perrault designed a female university building of a much larger scale than that of the library designed twenty-three years prior, exploiting the form reminiscent of female anatomy, but muting its presence within the context of its built environment. Is it the architect’s gender that determines, or carries the responsibility for, the inclusivity and fitness of public spaces?

Alice T. Friedman notes that any substantive discussion of female clients as collaborators in design or as catalysts for architectural innovation is missing from the history of architecture. By neglecting the role of convention and gender ideology in shaping both architecture and social relations, historians highlight individual creativity, perpetuating the false notion that buildings are to be valued as isolated art objects.21 And while Friedman explores the challenging roles of female patrons and clients, and the value of their unconventional approaches to the requirements of modern living, her research inevitably focuses on a limited number of houses, at the beginning of the twentieth century, for wealthy women whose architects may have been their family friends, sons or lovers, and whose means came from their husbands or fathers. The pinnacles of the ‘women’s space’, historically, are a handful of modest houses, sometimes born out of close relationships between clients and architects.

We are a century removed from Truus Schrӧder-Schrӓder’s house. The two years of the pandemic22 have proven that working from home, with flexible working hours, is not a failure of professionalism but rather an opportunity to improve the quality of life. The experiences of the lockdowns during the pandemic have highlighted the shortcomings of the rationed, modern dwelling, which typically lacks additional, dedicated, work space. And while many women celebrated the victory of flexible hours and reduced commute, as a result of the pandemic enforced arrangements, they found themselves spending office hours in their open plan kitchens, surrounded by home schooled children, laundry, grocery deliveries and home maintenance. Working@home survey found that women are still significantly more likely to undertake all or a majority of domestic chores and caring responsibilities in their households, reproducing and reinforcing gender roles.23

Although varied across time as well as scale and typologies, all of the examples illustrate somewhat missed opportunities to radically change women’s historical, archetypal condition. Deeply embedded cultural values, or personal circumstances and experiences, they are the physical realisations of inherent limitations and invisible constraints. If we could shift the focus in architecture from the formal conventions and stylistic values to the built environment’s embodiment of traditions, cultures, identities and social relationships we would, despite the existence of some brilliant examples, find little change and improvement in the overall picture. It is here that the problem of ‘tradition’ resides. The rigidity and longevity of the built poses its volume as the accurate and tangible historical representation. As such, it offers a precedent as much as it represents a norm. The trajectory of female emancipation is one not developed alongside her biology and spirit, but rather one which has dis-morphed in its attempt to adjust to the tracks of the established norms.

“And thinking of the safety and prosperity of the one sex and of the poverty and insecurity of the other and of the effect of the tradition and of the lack of tradition upon the mind of a writer… …for we think back through our mothers if we are women.” Virginia Woolf24

In 1949 Simone de Beauvoir stated that “it is not nature that defines woman; it is she who defines herself by dealing with nature on her own account in her emotional life”25 but concluded her writing with: “in beginning to exist for herself, woman will relinquish the function as double and mediator to which she owes the privileged place in the masculine universe”.26 And it may be precisely this historical burden of a woman’s biological characteristics, which define her psychological disposition, that contributed to the erosion of her emancipation: the recognition of gender equality takes place in the carvings of patriarchal society and culture, populated with the grooves which can only be filled by altered forms of femininity. Thus, our built environment stands as a reminder to women of the inadequacy of the given form to the functioning of her life.

Can the social order and traditional cultural values be changed through spatial means? Besides, is an evolution of built typologies possible if all the ‘changes’ begin from, and focus on, the domestic and residential domains? Assuming the passive role in society throughout time, women have been modernised, and they have appropriated modernity, conquering their own micro-spaces within the given structures. Historically, women are defined as “other” and it is from this marginalised position that women are exploring history, uses of public space, consumerism and the role of domesticity in search of ways into architecture.

“It is simple: People produce works, and we do what we can with them, we use them for ourselves” Serge Daney 27

As a set of activities linked to the service industry and recycling, postproduction belongs to the tertiary sector, as opposed to the industrial or agricultural sector, i.e., the postproduction of raw materials28. Women are, therefore, the post-producers of space. Spaces which are already in circulation, of defined function and typology are essentially being serviced by women, and in that process appropriated, re-created or saturated, and to some extent attributed to women. The established theoretical frames, no more than spatial and physical environment’s ones, do not recognise the need for radical transformation, in the same way they recognise female presence as an additional one. In the clandestine realm of the relationship between architectural and social space, blurred by the recognition of the tensions between public and private, the pursuit of feminist spaces becomes a diluted aim, involving all marginalised social groups and social justice. And here women find themselves returned to their archetypal definition: that of carers, dedicating themselves to others from the position of the ‘other’.

Architecture must give us the room of our own, where privacy and disposition will not come from Eduardo Paolozzi’s pleasure29 but from the potential of the space: social - constructed and realised. If womanhood is a protected occupation, confined in the domestic, banal and relegated, should we not radicalise the site of our entrapment and re-programme our homes? Architecture may be the point of departure in the new modes of postproduction of our homes, neighbourhoods and wider landscapes, which are slowly dissolved by the chaos of the digital - that doesn’t recognise domesticity. Reprogramming before revolutionising.

Women in architecture for women in architecture….