Introduction

Contemporary urban development has marginalised, if not dismissed, playground areas. On one hand, the gaming environment has shifted to a virtual realm, involving how problem-solving abilities are acquired during children’s development (Chuang & Chen, 2009; Craig, Brown, Upright, & DeRosier, 2016). On the other hand, mechanisms of privatisation of leisure time have embedded outdoor activities in indoor controlled environments, such as malls (Jäger, 2016) or the family home (Allan & Crow, 1991). Against this background, traditional open-air play areas are being neglected. Concerning the individual, playing becomes an essentially visual experience, and poses no motor-physical challenges to the gamer. Regarding the environment, indoor play areas target an audience of consumers rather than that of a community, and employ standardised equipment.

The text aims at revisiting the centrality of playgrounds in housing complexes, arguing that such areas should gain visibility in the contemporary discourse on public housing. Spaces for children can still function as meeting places because they occupy a physical and socio-cultural dimension of in-betweenness. This idea is underpinned by an examination of experimental projects carried out in the 1950s-70s, when the spatial turn of social sciences was accompanied by interdisciplinary architectural studies that borrowed methodologies from education science, sociology, anthropology, and psychology. Looking at the future of playgrounds, though relevant designs constitute today only a small niche of architectural production, we have identified exemplary experiences that signal original approaches to shaping children’s environments. We will respond to the question of what we can learn from post-war playground projects, concentrating our attention on how play areas were catalysts of community building and vectors of a new spatial organisation of neighbourhoods. Today, Living Labs may pick up the baton of such a complex vision and project it to a perspective of playgrounds as meeting places. Voytenko et al. (2016) emphasised that Living Labs have no uniform definition, though it is generally accepted that they are “living” because of real-life settings, and “labs” for their experimental nature (Schliwa, 2013). The concept is credited to MIT professor W. J. Mitchell for the study of smart domestic spaces like PlaceLab, inaugurated in 2004 (Dutilleul, Birrer, & Mensink, 2010). Because they are a powerful tool to elaborate, analyse, and refine original solutions in a real-life context with public-private partnerships (Resta, 2021), in our view, the Living Lab ecosystem is ideal for reinvigorating post-war playground experimentation in the contemporary city. The living laboratory is an urban setting where research and implementation address problems in their real-life setting (Alavi, Lalanne, & Rogers, 2020). On the institutional side, artists, architects, and urban planners can now rely on a regulatory framework that favours laboratories previously conducted informally (see the case of Lady Allen and Riccardo Dalisi). Co-creation design processes are supported at all scales, from local municipalities to European Commission programmes, provided with custom funding schemes (Schumacher & Feurstein, 2007). We believe that this juncture allows to develop on-field research and projects in which the participatory dimension can be naturally associated with the design of playgrounds in housing complexes, revisiting the concepts of participation and aestheticisation that will be discussed later.

First, the text will lay out the conceptualisation of in-betweenness, as it is the theoretical perspective that spatialises the status of playgrounds in housing complexes. In the following paragraphs, we first examine how post-war social housing got entwined with the raising awareness on children’s development theories. In the second part, we review four landmark case studies, grouped under the concepts of participation and aestheticisation, highlighting their innovative approach to the architecture of childhood. Finally, we select two possible best practices in today’s panorama, Céline Condorelli and Assemble collective, with a view to future strands of development in connection to Living Labs models and participatory practices.

The concept of in-between in architecture

The concept of the in-between is present in different disciplines and generally indicates areas that are shared by different constituted entities. Austrian philosopher, pedagogue, and theologist Martin Buber (1878-1965) was the first to introduce the word in-between to underpin his dialogic existentialism. He argued that the reality of human life lies in the relationship between one being and another. The communication between two beings emerges in a common sphere called the in-between, the starting point for the real third (Farhady & Nam, 2009). This starting point is the sphere where two entities establish a dialogue that can be conceived as the base of sociality. Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) then developed the idea of in-between with a spatial meaning. According to the German philosopher, the in-between is an interval, an interstice that becomes evident with the differences, allowing humans to understand space (Heidegger, 1954).

The in-between entered the architectural debate at the time of Modernism, and especially due to architect Aldo van Eyck (1918-99) as part of Team X. The group included international thinkers who opposed the paradigms of modernist architecture with a humanistic stance. Concepts such as place and occasion replaced space and time. As the Italian architect Giancarlo De Carlo (1919-2005) stated, the place is a space inhabited and lived by real men and women, hence avoiding the abstract theorisation of people that is at the base of standardisation processes (De Carlo, 2004). Aldo van Eyck introduced the concept of place as strictly connected with that of situation, discussed by Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-80) in 1943, as well as the concept of in-between by Martin Buber applied to architecture (Lefaivre & de Roode, 2002). According to this view, the city is a given urban setting in which planners should adapt instead of imposing authoritative top-down designs. In the book The child, the city and the artist van Eyck expressed his theoretical proposition of the in-between and the potential of liminal spaces in the public realm as the perfect locus to develop a dialectic reconciliation of conflicting actors. Later this took the name of twin phenomena (van Eyck, Ligtelijn, & Strauven, 2008), a non-conflictive or mutual dialogue between two halves of the same entity. Namely, a place where two polarities are simultaneously present as if they were complementary colours. It is not a coincidence that both the theme of threshold spaces and that of child-centred urban design were present in the last three CIAM (IX, X, XI) under the influence of Team X (Kozlovsky, 2013). At the CIAM X in Dubrovnik, van Eyck himself presented his ongoing work on Amsterdam playgrounds with four illustrated panels, receiving praises from Peter Smithson (1923-2003) and John Voelcker (1927-72) (Ligtelijn, 2019).

In architecture, the in-between is considered the space of relation and dialogue between different things, space, and humans. As stated by Teyssot (2000), the world and the things don’t exist next to each other but mutually permeate themselves. The transition space is the place par excellence where this theoretical concept succeeds. Here is important to highlight that in-betweenness implies transition, in both dynamic and static forms. In other words, transition is the act of crossing boundaries. Herman Hertzberger looked at the in-between through this perspective, the threshold, as the key to a transitional connection between areas. In turn, the connection creates a dialogue between different realms generating a non-hierarchical conception of space. Intermediate spaces, spaces of transition, semi-public and semi-private spaces were complemented by the discourse on the surroundings, the extension of housing, threshold and passages involving a different point of view on city-architecture relationship (Moley, 2006). In design terms, this theoretical formulation can be explored, as van Eyck and others did, through the study and realisation of playgrounds. The attention paid to the child’s point of view dissolved the standardised Modernist subject/urban dweller, paralleled by a loosening of the hierarchical logic that governed urban planning in the first part of the twentieth century. Thanks to new ludic areas, bombed sites or leftover spaces in peripheral neighbourhoods were transformed in meeting places.

Post-war social housing and the playground

Until the end of the nineteenth century, the act of playing in urban areas occurred essentially in the street, also provoking constant danger for children. Public areas dedicated to play first appeared in the form of “sand gardens” in Germany (Sio, 2018), and consequently, they were characterised by minimal standardised elements in solid steel, such as swings, slides, and climbing structures. The playground was a response to creating a safe place for ludic activities and social gatherings among children and families. The concept started to be developed in the nineteenth century thanks to pedagogue Friedrich Fröbel (1782-1852) and his educational model of playing for learning, for play “is the highest phase of child development-of human development at this period; for it is self-active representation of the inner-representation of the inner from inner necessity and impulse” (Fröbel, 1887, pp. 54-55). Social reforms followed theory, and cities started to adopt designs of equipped recreational areas that were deemed essential for the formation of new generations. Before the Second World War, Denmark, Sweden, and Holland led the implementation of new concepts elaborated by paediatricians and psychologists, focusing on free play (Burkhalter, 2016a).

In the post World-War-II period, “Western Europe concentrated on rebuilding its future through a shared concern for children. It is not accidental that the most important buildings of the period were designed for children” (Kozlovsky, 2013, p. 18). The reconstruction phase prioritised new housing policies and social amenities in an attempt to rethink the early-Modern built environment (Diefendorf, 1989; Wendt, 1962). Public housing targeted predominantly low-income households, was provided by public authorities or non-profit organisation, and incorporated rental schemes. Because of the high density of expected occupants, amenities such as car parking, gardens, children’s playground, and sports facilities, had to be embedded in the new housing policies. The widely used “C” typology allowed to create a semi-public space in the centre, where such amenities could be arranged. Additionally, the concave space of the courtyard mediated between the metropolitan scale of the suburbs and that of pedestrians and families living in the neighbourhood. Given the in-betweenness of these spaces, we argue that the playground, and outdoor ludic activities in general, were, and still are, crucial for mass housing complexes. Many scholars asserted the decline of post-war mass housing due to physical, social, and economic factors (Power, 1997; Skifter Andersen, 2003; Temkin & Rohe, 1996). Their playgrounds declined even faster because they require collective care and maintenance. Under the influence of Clarence Perry’s neighbourhood unit on European planning theories, the presence of a playground was considered an essential element of housing already at the earliest stages of Modernism. Its absence was mentioned as a clue of low-quality projects in the first debates of the 1970s (Belli, 2022). This demonstrates the entanglement of ludic areas with qualitative social housing.

In the 1970s, American psychologist James Gibson (1904-79) strengthened further the relation between environment and perceiving subject by proposing the affordance theory. Affordances, intended as the opportunity for action provided by a particular object or environment, are what an infant first notices, and only later formalises with a meaning (Gibson, 1979). This theory extended the vision on the importance of the design of the urban environment by adopting an ecological approach in connection with psychological issues (Withagen & Caljouw, 2017). The open-air environment is full of possibilities for action, and playgrounds specifically support the social and creative experience of children. The historian Johan Huizinga (1872-1945), for instance, in his well-known book Homo Ludens, studied the importance of the act of marking out spatial delimitations as the origin of playgrounds. Within their area, certain moves have special meanings and rules that apply inside but are not valid in the outer world. The arena has a ritualistic, almost magical, aura because elements form a symbolic system that establishes a displacement in time and space. The definition of a specific transition from one space to another gives value to play and creates a shift of conduct in the children or those who occupy that space. Huizinga studied play in various aspects of human culture and conceived play as the direct opposite of seriousness, evoking an inevitable change of behaviour and deconstructing serious and established aesthetic values (Huizinga, 1949).

Collective spaces are then the locus of transition between domestic and urban realm physically, figuratively, and socially. In their analysis of spaces of transition in London post-war housing, Semprebon and Ma (2018) highlight how significant Thatcherism was for the obsolescence of the collective ideal, in turn leading to the abandonment of shared areas even in complexes with high quality designs. Alongside the experimentational nature of 1970s architecture, one should consider the development, in that period, of a separate field of study, architectural psychology, which explored causal relationships between the built environment and behaviours. Considering the child’s figure as the creative and playful potential in all human beings (van Eyck et al., 2008), playgrounds can serve as meeting places in the urban realm.

Four models: Experimental playground designs during the post-war period in Europe

After the traumatising period of the war in Europe, the design of amenities for children aimed to provide interaction and create a sense of community, distant from a past full of violence. Children were considered a fundamental component of family life and of social stability (Sio, 2018). The first public areas often replaced bomb sites. These neglected and abandoned areas of the city were adapted to overcome the scenery of war destruction by changing the significance of collapsed structures into adventurous fields. Having dilapidates sites at hand, Lady Allen of Hurtwood (1897-1976) suggested such convergence in her essay Why not use our Bombed Sites like This? (Kozlovsky, 2013).

During the 1950s and 60s, a new optimistic perspective surfaced, and the baby boom generated the proliferation of families looking for comfortable places to live. As mentioned above, the design of common areas in modern housing projects was crucial to offer something more than just a stack of flats. The space between the public realm of urban life and the private sphere of home was designed to host children, boys and girls, that would gather, grow together and experience life close enough to home to feel safe but also far enough to experience adventures. The potential of the transition space lies in this feeling of built homecoming. As stated by van Eyck, it is the capacity of the liminal space “to provide a climate congenial to man equipoise” (van Eyck et al., 2008, p. 70), which is a sensation of comfort rendered by the space surrounding us. Along the same line, Alison (1928-93) and Peter Smithson implemented in their theory and their projects the condition of liminality through a reinterpretation of urban elements in social housing complexes: “the street is an extension of the house; in it children learn for the first time of the world outside the family; it is a microcosmic world in which the street games change with the seasons and the hours are reflected in the cycle of street activity” (Smithson & Smithson, 1968, p. 78).

Hence, the playground is not only physically in between domesticity and urbanity, but also retains a loose connection with the family nucleus while allowing limited freedom for exploration and socialisation. Especially in the social housing context, this condition was predominant. Denmark was one of the first countries to introduce playgrounds in social housing, starting in 1943 with the Emdrup housing estate in Copenhagen. Then the junk playground was implemented programmatically in the city following the idea of landscape architect Carl Theodor Sørensen (1893-1979). His work became an inspiration for a new way of conceiving playgrounds, as will be explained later through the case of Lady Allen. In the same years, architects of Team X and their associates discussed ways of interpreting the role of architecture embedding social values, criticising Modernism and investigating alternative architectural processes. It was an important moment of experimentation for architecture, and playgrounds were a stimulating field of action. What follows is an attempt to debate this problematic relationship between play areas and residences through four case studies, four modes of interpreting the changed role of architects and artists vis-à-vis post-war reconstruction. We have identified two main design approaches, each comprising two case studies, that took place in Europe between the 50s and the 70s: participation and aestheticisation. Though all cases cannot be classified unequivocally under one or the other, it is useful to trace commonalities in their design strategies to learn from such experimentation. The selection considered the most recognisable playgrounds in Western Europe that are reviewed in literature (Frost, 2010; Kozlovsky, 2013; Sio, 2018), and specifically the selection made for the exhibition The Playground Project, curated by Gabriela Burkhalter, at the Kunsthalle Zürich from July to October 2016. The exhibition featured fourteen artists, architects, and landscape architects (Burkhalter, 2016b). Four are considered to be representative of the design approaches proposed in the text and with a sufficiently diverse geo-cultural background: Lady Allen of Hurtwood, Riccardo Dalisi (1931-2022), Aldo van Eyck, and Group Ludic. They either worked during the World-War-II reconstruction (Lady Allen and van Eyck) or within radical movements of the 70s (Dalisi and Group Ludic). With a view to correlate their design process with Living Labs, we will emphasise the open-endedness of their composition, situating the polycentric nature of their layouts as the focus of children-space interactions. Finally shaping meeting places for the neighbourhood.

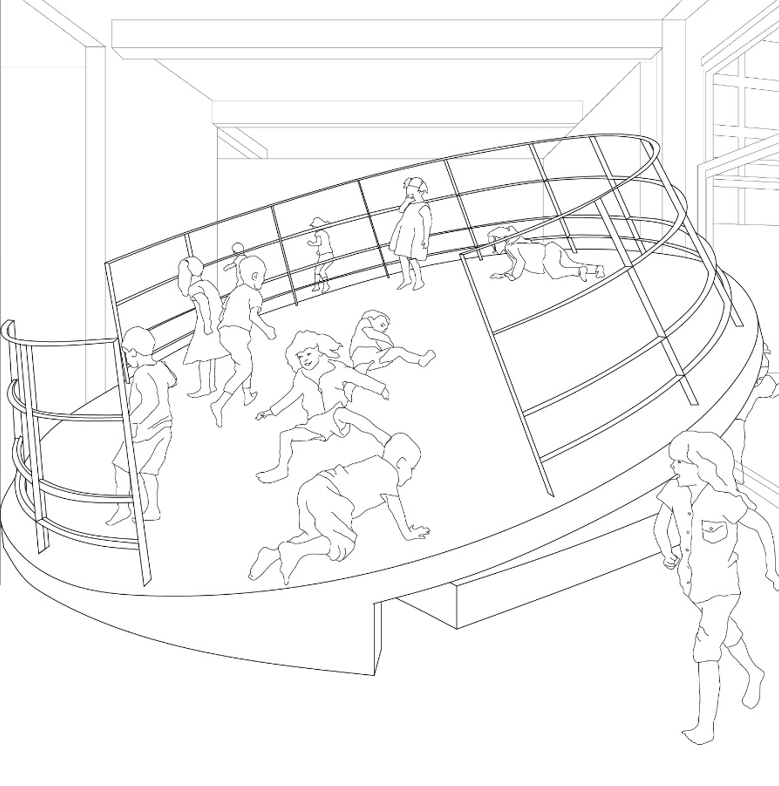

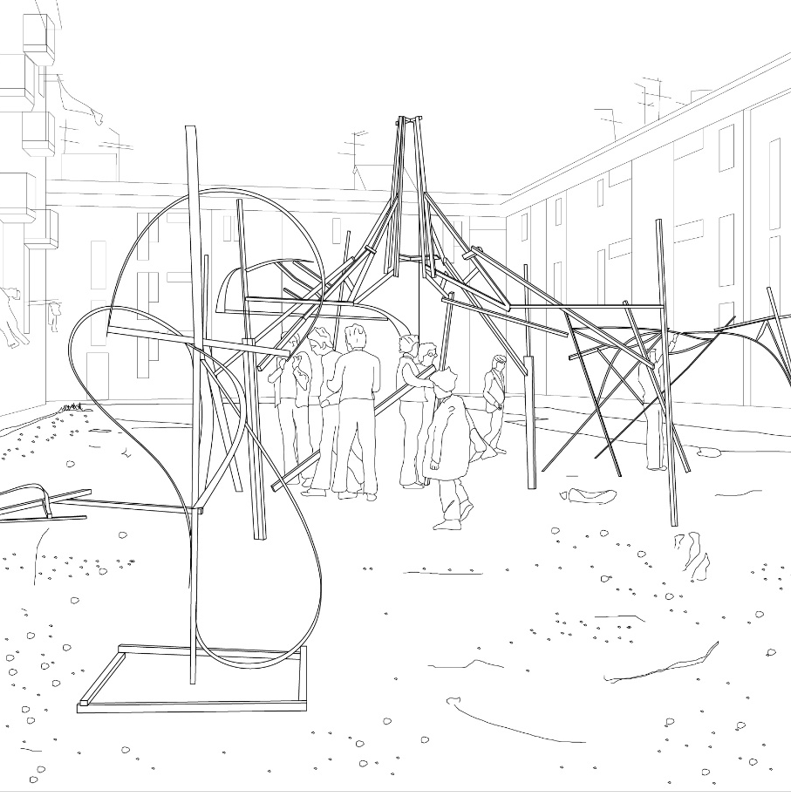

We have illustrated each case with one scene, re-elaborated from archival material, highlighting the playground equipment, the spatial morphology of the surrounding, and the physical effort posed by the playthings (Figure 1, 2 and3).

Drawing by the authors. Based on a photo by Bela Zola in Clydesdale Road, 1955

Source: Figure 1 Lady Allen of Hurtwood, adventure playgrounds with found objects in a bombed site

Drawing by the authors. Based on a photo in The Playground Project (Burkhalter, 2016b), 1975

Source: Figure 2 Riccardo Dalisi, animation workshop in the Traiano neighborhood

Participation

Participatory approaches consider the laboratory component as the main feature of the design process, which leads to an ecosystem for social cohesion (i.e., the aforementioned Living Lab). The participatory nature of co-design defies the assumption of the architect-planner-artist as the sole author of urban transformation, opening the field to a shared creative process. Arts engagement had a first turning point in the 70s with the so-called radical collectives. At a later stage, Bourriaud's Relational Aesthetics, elaborated in the late 90s, set the theoretical ground for artworks concerned with social relations. The city itself, Henri Lefebvre (1901-91) suggested, is a work of art (Lefebvre, 1996). Participation is enacted through mechanisms of empowerment: Zamenopoulos et al. (2021) organise co-design empowerment in three main interrelated aspects: the loci of empowerment, the conditions of empowerment, and the different manifestations of empowerment. When empowerment is rendered in the frame of a playground design, individuals, a community, or a particular institution gains decisional power. Hence, influencing decisions on the design of the built environment is the very application of empowerment, which in turn may clash with the classical prerogatives of urbanism and architecture as disciplines (Resta, 2021). As it will be seen in the following cases, Lady Allen and Riccardo Dalisi were more than designers: the former lobbied for children’s welfare in the political sphere, the latter showed new radical ways of teaching architecture. Both entertained a close dialogue with the community and relied on do-it-yourself constructions.

Taking Risks: Lady Allen of Hurtwood - 1950s

Lady Allen of Hurtwood was one of the first intellectuals to defy the deprivation the younger generation was suffering after the war. Formed as a landscape architect, she dedicated her life to studying children’s well-being. She is now considered one of the most prominent figures in promoting play projects in the UK (Ashley, 2016). In her life, she advocated for children’s rights to a fair education and constantly brought her instances to an institutional level. She was awarded various roles: vice president of the Institute of Landscape Architects and the Nursery Association of Great Britain, Chairman of the London Adventure Playground Association and the Holiday Club for children with disabilities (Anonymous, 2011). Being a pacifist, she wrote in Memoirs of an Uneducated Lady, “I could take no part in the war effort, but I could help the children” (Allen & Nicholson, 1975, p. 150), especially those with special needs. Lady Allen discovered the adventure playground model developed by Carl Theodor Sørensen in Denmark. Sørensen observed that children are attracted by junk materials such as sticks, stones, boxes, and ropes more than in traditional playground equipment (Papastergiou, 2020). Intrigued by this anti-aesthetic approach to design, Lady Allen followed up on Sørensen’s idea by envisioning play areas in combination with her studies on children’s education. She decided to start from neglected areas in difficult neighbourhoods of the city to help the young population live better. Concerned by children living in high-rise complexes with no places to play, she used liminal areas, “SLOAP” (Spaces Left Over After Planning), to strategise an antidote to juvenile delinquency (Sio, 2018). Hence, Lady Allen’s attention was all concentrated on the Modernist built environment, which was deprived of natural elements such as water and sand, an eminently artificial realm, where children either risked injuries or were kept confined in their domestic bubbles. Her idea was that of a playground design providing controlled risks. As a researcher and writer, she studied the theory of play, publishing pamphlets such as Design for Play (1961), New Playgrounds (1964) and the seminal book Planning for Play (1968). She noticed that freedom of play helps children overcome risks, become more independent and acquire the ability to count on their resources when faced with an obstacle (Allen, 1968). In Planning for Play, she underlined the importance of taking risks, “experiment with earth, fire, water and timber, to work with real tools without fear” (Allen, 1969, p. 55). The stress is on the materiality and do-it-yourself activities, “they can create and destroy, […] they can build their own world with their own skills at their own time and their own way” (Tovey, 2007, p. 49).

The ideation phase consisted of a participatory design process with the future young users as stakeholders. All playgrounds were built with the contribution of children, parents and volunteers, operating as independent associations formed by local communities (Papastergiou, 2020). The first experimentations, between 1948 and 1960, were located in high-density housing developments readapting bombed sites in the urbanised area. Lollard Street (1955-1960) and Clydesdale Road (1952-55), both in London, were the first areas targeted by Lady Allen. Then Liverpool Hull, Coventry, Leicester, Leeds, and Bristol followed. Each playground story unfolded throughout a unique process in which various actors had to find a power balance on the management of the areas. And this is still the main concern in contemporary Living Labs implementation (Nguyen, Marques, & Benneworth, 2022). Lollard’s initiative started in 1954 with the formation of a voluntary association of local residents, having Lady Allen as chairman. They asked the London County Council to organise a playground on the site of a bombed school, just across the river from the House of Parliament. The area was leased at a symbolic rent, in addition to an annual grant, that showed good will from the administration. Though, the reaction of the residents was mixed, “the materials provided for the children's use disappeared mysteriously, on bonfires and elsewhere; and the neighbours had not got out of the habit of dumping rubbish as soon as one lot was cleared up” (Nicholson, 1959, p. 2). But it was regularly visited by around 500 children. Teenagers were also involved in self-construction activities in collaboration with local old-age pensioners (Lady Allen Of Hurtwood, 1958). Finally, it was closed when the school was rebuilt.

The Clydesdale playground similarly departed from the initiative of local residents, in Paddington, willing to recover another bombed site that was used to dispose garbage. Also, activists from the pacifist association International Voluntary Service for Peace contributed to clear the site in collaboration with children. The project faced scepticism in the first two years, until the unfolding of inclusive activities strengthened ties between users, play leaders, and the community. Clydesdale triggered civic participation during its five-year lifespan, becoming a model playground that was later used as a benchmark for the adventure playground movement (Kozlovsky, 2013).

Projects were truly adventurous, and to a certain extent, dangerous as well: only children around seven or older were admitted to playing alone. In contrast, younger children had to use the facility under the supervision of an adult. Overall, these areas were characterised by ephemeral and unconventional structures made of poor material, found objects, distant from a clean layout drafted on the drawing table (Figure 1). On the contrary, the ugly and shabby aspect of Lady Allen’s playgrounds built the basis for a more radical idea on children’s development, in opposition to the poetic function of play as was intended before the twentieth century. Drawn by anti-idealization and, by extension, anti-aestheticization, the ludic areas promoted by Lady Allen transformed the theory of play, having at the centre the idea of taking risks, in environments with a traumatic past. Such playground had to emphasize the “need for freedom, and even anarchy” (Burkhalter, 2016b, p. 52) with the highest degree of freedom.

Didactic value: Riccardo Dalisi - 1970s

Riccardo Dalisi was an Italian architect whose position similarly explored anti-design and the imaginative potential of creation against functionalism. His work can be ascribed to the broader current of radical architecture as he was one of the members of the experimental educational program Global Tools (1973-75). Unlike most of his Italian colleagues, he developed his theoretical propositions in practice through on-field animation involving disadvantaged people (Pioselli, 2015). Rather than employing performative actions, Dalisi opted for laboratories involving people that lived in social housing complexes, especially children who often dropped out of school. In the metropolitan area of Naples, Riccardo Dalisi started experimenting with his student from the Napoli’s Faculty of Architecture Federico II. His academic research focused on the social role of the artist and artistic practices via artifacts made of tecnologia povera (basic/poor technology). According to Enrico Crispolti (1933-2018), art critic and curator, participation and cooperation were significant in developing a cultural vision of the suburbs, the small town, and marginalised areas (Pioselli, 2015). From 1971 to 1974, the activity developed by Dalisi in the Traiano neighbourhood concretely tested theories on social animation and participation. Crispolti highlighted that the Traiano was not a finished project, but a methodology that the young Neapolitan architect refined over the years; symptomatic of how the architectural debate was incorporating civic engagement (Crispolti, 1993). Dalisi and his student kicked off a laboratory consisting of a program of activities with children living at the Traiano, whose image was characterised by a high level of criminality combined with a degraded urban environment. The Traiano had been built in the 1950s-60s in a desolated peripheral setting. After an initial moment of friction with the animators, children started to draw and create forms (Figure 2). The initial relationship is established with pocket money offered by Dalisi to convince the youngster to participate in the laboratory. Eventually, a mutual exchange takes place between students/architects providing materials and the chaotic young community proposing experience-based ideas (Catenacci, 2015).

Similarly to Lady Allen, Dalisi also intended the design of a playground as the re-signification of ordinary materials and objects, nearing the idea of participatory architecture developed by Giancarlo De Carlo, namely a nonlinear unfinished project based on dialogic formulations (De Carlo, 2013). Dalisi conceived participatory design workshops to build simple and ephemeral elements interpreting traditional techniques accessible to everybody, and involving children to lay out their own playgrounds (Felicori, 2022). Traiano workshops hinged on manual skills and bricolage in a way that “the design is not the initial phase of the work, as it usually happens in architecture, but the outcome, the final unveiling of a concrete activity” (Bonito Oliva, 1993, p. 21). Within the scenery of derelict public areas where neighbourhood amenities were never provided to the population, in-between anonymous baracche in the Neapolitan neighbourhood, the imagination of the children would augment the concrete materiality of that simple equipment to become magic realm. Indeed, Dalisi’s aim was to transfer new tools to the kids to reach a higher degree of self-empowerment in shaping their environment (Burkhalter, 2016b). Additionally, the educational value of Dalisi’s workshop had two layers: one was aimed at the youngsters living in the Traiano, the other at the students of the faculty of Architecture, both receiving an informal education while working on a project with different roles. As an example, the projects archived in the Frac Centre-Val de Loire under the name Tecnica povera, Ateliers de design participatif, 1972-1978, show pieces of furniture by a team comprising one animator-architect, three to four architecture students, and one local child who sketched the idea (Frac Centre-Val de Loire, 2018). In his account of the Traiano workshops, Dalisi reflected on the degrees of involvement of the neighbourhood. First children drafted drawings of furniture on paper, fabric, and wood. Later their mothers and sisters helped with embroidery and sewing. He defined his role as “aesthetic operator”, one that breaks the conventions of high and popular culture, performing exactly the same activities the children do (Dalisi, 1993). The four-year activity in the neighbourhood led to the proposal of a kindergarten in Traiano, which was never completed. It was designed in 1969-71 in one of the basements of the complex and together with the children that would have used it (Catenacci, 2015). Compared to Lady Allen’s, the organisation of the Traiano activities was purposefully chaotic, with no formal association or committee to preside over the area.

His work on the definition of a collective identity, one that would make an inhabitant of the most remote suburban development proud, continued after 1974 with other experiments in Naples. Also, accompanied with theoretical books such as Architettura d’Animazione (1974) and L’Architettura della Imprevedibilità (1969). The former is a curated diary of the Traiano experience, with critical reflections on the word animazione that was being already stereotyped among architects. After Traiano, he was involved with associations advocating for human right to housing. Dalisi worked on several other projects with a different societal composition: i.e., in Ponticelli, with the elderly population, in courtyards of traditional farmers’ housing, and in the historical centre of Naples, the Rione Sanità, with tinsmiths of Rua Catalana (Pioselli, 2015). Ponticelli’s Casa del Popolo became an example of how to integrate avant-garde artistic research with the daily life of retired workers. Also, Dalisi moved there the location of his university courses, in connection with the inhabitants of the neighbourhood, as he was convinced that addressing the social issues did not concern the drafting of architectural projects, but the act of use and organisation of urban space on-site (Corbi, 2004). Overall, this reinforced his position on viewing the city as a learning environment, and vice-versa educational institutions to be organised in relation to societal needs (Dalisi, 1967). In the Neapolitan area, Dalisi’s path was followed by several other groups and individuals such as A/Social group, Gruppo Salerno 75, Vincenzo De Simone, and Gruppo Humor Power Ambulante, as was documented by Crispolti at the 1976 Venice Biennale (Catenacci, 2015).

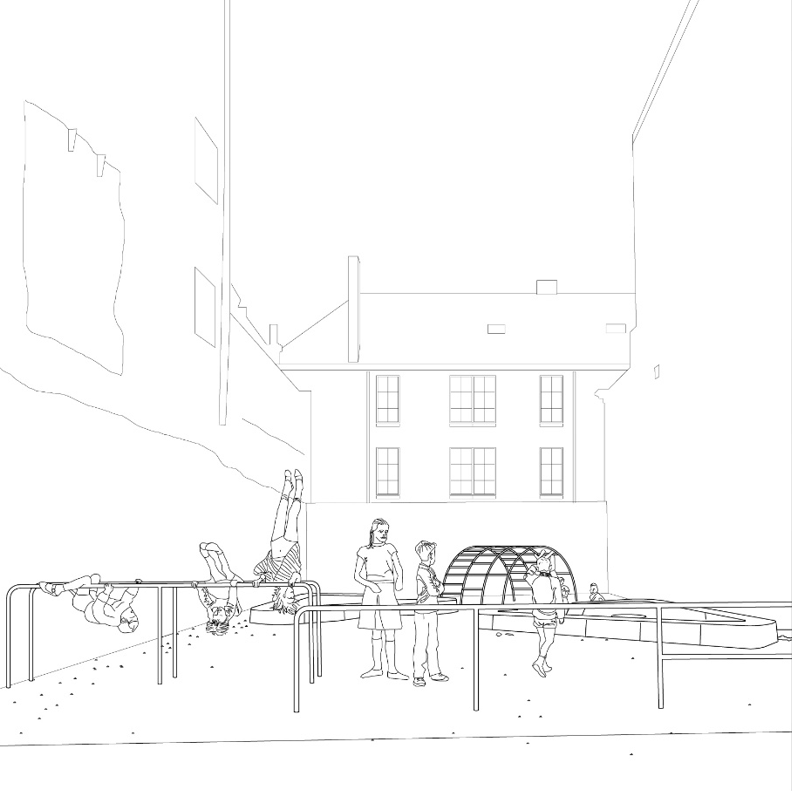

Drawing by the authors. Based on a photo by Ed Suister of the Laurierstraat playground, 1960s

Source: Figure 3 Aldo van Eyck, playground in Amsterdam in a leftover urban space

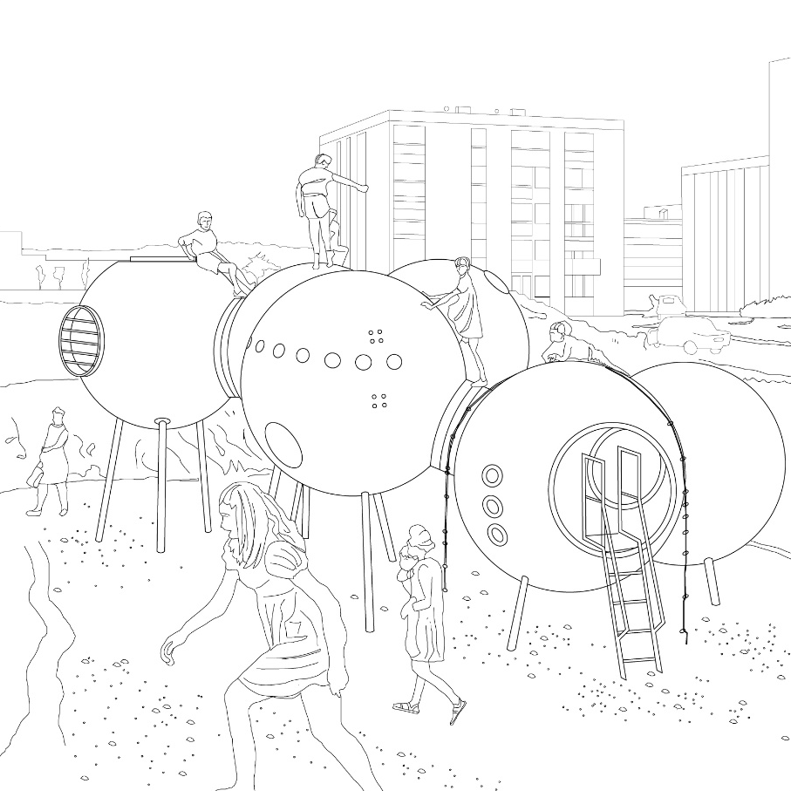

Drawing by the authors. Based on a photo in The Playground Project (Burkhalter, 2016b), 1968

Source: Figure 4 Group Ludic, modules of a playground in Hérouville-Saint-Clair, France

Aestheticisation

The aestheticised playground relies on forms and their relational connection with the user. Affordances, as mentioned above, are moments of psychological response to the features of the environment. Van Eyck’s and Group Ludic’s playground environments successfully offered a field of affordances to children instead of a traditional layout: their shapes have no obvious meaning nor function. The design was open to interpretation, especially for young users whose meaning-making system has a high degree of flexibility (Haynes & Murris, 2013). Hertzberger discussed the issue in relation to his design of the Montessori Primary School in Delft: while the objects “exclusively made for one purpose, suppresses the individual because it tells him exactly how it is to be used”, the form should provoke an “act of discovery”, and its design “must be made in such a way that the implications are posed beforehand as hidden possibilities, evocative but not openly stated” (Hertzberger, 1969, p. 66). This indeterminacy is obtained in different ways. Van Eyck drew elements for playing as a kit-of-parts, forming a toolbox that could be adapted to any leftover space in the city; Group Ludic invented ways of disorienting the user with unfamiliar objects, activating their imagination through a vast range of configurations that any modular unit supported.

Toolbox: Aldo van Eyck - 1940s-70s

The research of Aldo Van Eyck in the aftermath of World War II has been previously defined in his theoretical concept as the main contribution to developing and enhancing spaces of transition. His work on the Amsterdam Orphanage became a model for the design of architecture for education, and in a time span of thirty-one years, he realised more than 700 playgrounds in abandoned or neglected areas of Amsterdam, creating numerous spots for social gatherings dedicated to the younger generations (van Eyck & Ligtelijn, 1999).

His work started in 1947 within the Amsterdam Department of Public Works. He surveyed the leftover spaces of the city, starting from residential suburban areas, to be filled with public play areas for children of different ages. The areas were not fenced; they let children play freely, inviting parents and guardians to oversee their play time and, consequently, creating meeting opportunities for adults (Withagen & Caljouw, 2017). Generally, such places were obtained from abandoned urban voids in the city, between residential complexes, creating a dispersed network of pocket spaces functioning as small squares. His design intention was to overlay “an additional urban fabric of public places where not only children gather but parents and the elderly too” (van Eyck & Ligtelijn, 1999, p. 68). This made the children visible in the urban realm. The overall project was aimed at humanising the city, as it was also elaborated in his theoretical production, to foster a dialogue in the community between children and their families. The constellation of play areas in Amsterdam was the actualisation of van Eyck's theory of the human being who needs to rediscover their child component (van Eyck et al., 2008).

Inspired by Constantin Brâncuși's, Hans Arp’s and Sophie Tauber’s sculptures, the essential toolbox of his playgrounds was composed of elementary forms such as circles, squares and triangles (Figure 3). Plastic outcomes were in line with Dada and Primitivist aesthetics (Navarro, 2018) while his compositional techniques hybridised classical and anti-classical strategies (Lefaivre & Tzonis, 1999). Simple and minimal equipment formed a kit-of-parts of abstract elements, resonating with Gibson’s affordance theory. Van Eyck intentionally designed objects with no definitive meaning. The abstract play elements were conceived as “tools for imagination” (de Roode, 2002) to spread creativity. Abstraction was the key to the success of his playgrounds, “while leaving room for interpretation rather than designing figures which he thought were didactic and architecturally incongruent” (Navarro, 2018, p. 53). His collaborations with the Cobra group of painters helped him explore the aesthetics of spontaneity that is at the base of bottom-up models. In this sense, according to Lefaivre and Tzonis (1999), there was a return to dirty reality, to the interpretation of genius loci departing from the conditions of the immediate surroundings of each site. Examining the dynamics of such pocket spaces, it is possible to draw a connection between van Eyck’s playgrounds and the cybernetic theory elaborated by Norbert Wiener as self-regulating entities evolving in successive loops of adjustments in response to their environment (Lefaivre & de Roode, 2002, p. 28).

Durable materials such as tubular steel and simple forms to be reproduced gave playthings the option to be installed in numerous areas. Hence, van Eyck’s playgrounds employed recurrent elements though being always site-specific. With minor variations and adaptations to the plot, two separate playgrounds never looked alike. Play equipment was designed in families of forms, in series of iterations and variations, descending from archetypal structures or spaces.

The success of Van Eyck’s playgrounds was, first of all, recognised by the communities, “the project took the city by storm” (Lefaivre & Tzonis, 1999, p. 17). The social impact was confirmed by people coming from different neighbourhoods who visited the first playground in Bertelmanplein, and were surprised by the positive impact it had on local children, in turn stimulating the construction of new playgrounds in other neighbourhoods (Papastergiou, 2020; Schmitz, 2002). Despite his vast architectural and theoretical production, van Eyck’s Amsterdan playgrounds marked a special turning point in practicing “an architecture of ‘community’ and ‘dialogue’ and of the human and formal building of the ‘realm of the inbetween’” (Lefaivre & Tzonis, 1999, p. 77). His work for the municipality established a method of urban intervention, later replicated in other suburbs of Amsterdam by civil servants, having small, circumstantial, situational planning as a starting point to transform the city. The management of spatial transformations resonates with cybernetic theory, which is also a theoretical framework employed for contemporary Living Labs applications in urban planning and design (Karadimitriou, Magnani, Timmerman, Marshall, & Hudson-Smith, 2022). At the institutional level, the influence of playgrounds reached Cor van Eesteren, head of Amsterdam City Development, as he shifted his attention to interstitial spaces and the importance to provide ludic areas in new post-war neighbourhoods (Lefaivre & de Roode, 2002).

Modularity: Group Ludic - 1970s

Repeating abstract elements were also the basic design feature elaborated by Group Ludic, French collective founded in 1967 by artist Xavier de la Salle, architect David Roditi, and filmmaker Simon Koszel. Between the 1960s and the 70s, as we have seen with Global Tools, revolutionary and transformative initiatives took part all around Europe, blurring the boundaries between architecture and performative arts. Group Ludic took on futuristic aesthetics over more than 100 playgrounds, play environments and public workshops. The trio aimed to compensate for the lack of play areas in France, expressing a multidisciplinary creative vision. Similarly to Lady Allen, they retained a strongly independent position, outside the conventional commissioning procedure, and pursued the implementation of new modules by producing prototypes (Burkhalter, 2016b, p. 119).

The first project was carried out in a Royan Holiday Village, far from the urban centre: it was a submarine silted up on the beach, made up of tubes, passages, and rooms where children would sneak into and hide (Revel, 2019). This project contributed to the formation of their language, convincing other holiday villages or new towns to revitalise the homogeneous built environment with their colourful and odd spaces for play (Sio, 2018).

In the middle of a flat expanse between large complexes in new suburbs such as Quartier de la Grande Delle in Hérouville-Saint-Clair, France, the playgrounds of group Ludic acted as alien objects, with uncanny shapes, to attract the attention of local children. Cube, pyramid and sphere were the three primary forms used in their projects. These volumes were designed to be inhabited, climbed, and explored as groups of forms assembled together. Their playground architecture was inspired by Buckminster Fuller’s and Frei Otto’s spatial structures, Yona Friedman’s ideas, Jean Piaget’s and Gaston Bachelard’s texts (de la Salle, 2016). When their modules were brought to the new satellite towns in France, Group Ludic encountered the difficult social condition of periphery and vandalism (Burkhalter, 2016b, p. 120).

Each group member had a specific role in inventing the playful composition. David Roditi was responsible for the production of forms and organisation of the assemblage, Xavier de la Salle handled painting and mobile sculptures, Simon Koszel elaborated the abstraction of forms and curated the general coordination of the elements (Donada, 2018). Individual modules were repeated and connected to each other to create a continuous system to be explored. The sphere was a perfect geometric template, produced using balloon moulds. The basic module was then always adaptable in multiple positions, it could be inhabited inside or climbed outside, and create the ideal environment of relaxation or gathering for the users. Through an isolation from the exterior world, each installation created microcosms provided with differentiated affordances, sometimes unexpected ones (Figure 4). Xavier de la Salle wrote that such use of elementary forms arranged in complex spatialities allowed children to appropriate the playground environment and transform it into “a cave, a space capsule, a deserted island, a pirate’s lair, a restaurant, a cotton-candy stall, and so on” (de la Salle, 2016, p. 203).

From 1968 to 1998, the realisation of playgrounds in new housing complexes also embedded methods of collaboration with young inhabitants. Using different forms and less durable materials, participatory workshops were the first experimental participatory actions in France in the 60s. Unfortunately, all the projects were abandoned and demolished because of the social changes in the neighbourhoods in which they were located. Often placed in isolated areas of the city, the playgrounds were increasingly associated with the stigma of dangerous places where illegal activities occurred (Burkhalter, 2008). But tough neighbourhoods, de la Salle wrote, were the real testing ground for their projects, where they drafted a “set of participatory guidelines subsequently followed by the team, […] yielding simple and efficient rules for project management” (de la Salle, 2016, p. 208). Not only the modules were prototypes, but the negotiation process as a whole.

Contemporary perspectives

In his foreword for the catalogue of the exhibition The Playground Project, Director of Kunsthalle Zürich Daniel Baumann pointed out that playgrounds have been overlooked by research institutions (Burkhalter, 2016b). Play areas have a potential to speak to a vast audience, composed of professionals and non-professionals, across all generations, and permeated of experimentational aesthetics. Compared to the post-war figure of artist-researcher involved in playground design with the community, what relevance has this issue today in literature? Analysing recent scientific publications, Web of Science database shows that in the last ten years, every year, ten to thirty-five scientific items contain both the word “playground” and “architecture”. Most items are published in Landscape Architecture (34), Sustainability (6), and Landscape Architecture Frontiers (5) especially by authors with a USA or Western European affiliation. The five top cited articles all relate risky outdoor play to healthy child development (Brussoni et al., 2015; Herrington & Brussoni, 2015) and only one tackles design features (Peschardt, Stigsdotter, & Schipperrijn, 2016). In architectural practice, the curated database of contemporary architecture projects Divisare.com returns 213 examples of realised playgrounds; Dezeen.com has 86 results; Archdaily.com shows 31 projects. One, the PXAthens - Six Thresholds, Kallisperi Playground, in Athens, has been nominated for the 2015 edition of the EUMiesAward. This demonstrates modest attention to design aspects in academia and little relevance of realised projects in mainstream outlets. Among the projects mentioned above, we have decided to discuss contemporary perspectives on playground design through two designers that focus their activity on children’s spaces, retain a participatory component in their process, are engaged with artistic installations, and explicitly refer to the historical precedents that we have mentioned above: Céline Condorelli and Assemble collective. Their work could provide hints on contemporary ways of thinking play areas while stimulating civic involvement and producing outcomes that are aesthetically significant. While both recognise the importance of the 1960s and 70s as the climax of architectural research on children’s spaces, Condorelli echoes van Eyck’s minimal and abstract equipment, instead Assemble with Simon Terrill elaborated on massive architectural elements to be found in housing complexes that were used as makeshift playthings.

Tools for imagination: Céline Condorelli

Céline Condorelli is a French artist whose research spans across art and architecture. She has an architecture training that informs her artistic activity aimed at exposing the social potential of architectural elements interpreted with a creative approach. Indeed, Condorelli pursued custom on-site installations rather than productions for galleries and museums.

In London, she co-founded the Eastside Project in Birmingham, an artist-run space based in a free public gallery in Digbeth and open to making art public (Eastside Project, 2007). The South London gallery asked her to develop a playground in the middle of Elmington Estate, challenging the idea of an outdoor exhibition and engaging the local community. The work was co-commissioned as part of Southwark Council’s Cleaner Greener Safer programme and installed in 2021 as part of South London Gallery’s Open Plan (South London Gallery, 2021). The outcome resulted from a participatory action in the neighbourhood “developed over several months with architect Johnny Cullinan, children and residents” (Condorelli, 2021). The installation was titled Tools for Imagination as a homage to Aldo van Eyck, who conceived the playground as a device to stimulate creativity.

Condorelli’s work on playgrounds started in 2016 for the exhibition Playgrounds at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), in which she designed carousels that materialised Lina Bo Bardi’s (1914-92) vision on what a museum should be. A place for culture and play open to society. In the same year, she worked on spinning tops during a residency at Kunsthalle Lissabon developing the work Models for a Qualitative Society, literally evoking Palle Nielsen’s (1920-2000) artwork The Model - A Model for a Qualitative Society (1968). The former is based on a 1965 playground design by Bo Bardi, which was never built, with three large-scale interactive sculptures. The latter was presented by Nielsen in an exhibition which transformed the entire Moderna Mussett - Modern Art Museum in Stockholm in an adventure playground. In turn, the two works were the starting point for the realisation of the work Proposals for a qualitative Society (Spinning) following an invitation by the Stroom Den Haag in 2017. At the Dutch art centre, the artist worked together with the museum staff and the curator of the architecture programme Francien van Westernen to involve children into the creation process of the artworks, namely choosing colours and forms of two carousels, the main sculptures of the exhibition (Condorelli, 2017). Embracing the same perspective of Lady Allen, the museum was transformed in a space open primarily to children, where they were free to use all kinds of tools and free to present their model of society through playthings. After the exhibition, the two carousels were permanently relocated to the playgrounds of two local schools in The Hague, the Yunus Emre School and the Nutsschool IBS Morgenstond, which contributed to the creation process (Condorelli, 2017). These three references on play as a transformative agency of public space are also addressed by the artist in a recent interview recorded for the embassy of Switzerland in the United Kingdom (Brinch, 2020).

Tools For Imagination provides a set of pieces of equipment, namely carousels, climbing structures and coloured surfaces (Condorelli, 2021), whose shapes have a level of indeterminacy that we have seen in Group Ludic and van Eyck. Some have an evident functioning; others need imagination and experimentation (Figure 5). Building on the existing conditions of the site and its relationship with the residents, this participatory work highlights the hiatus between the needs of a certain community and their practical concretisation, mediated by an artist that is capable of bridging the two dimensions. The research on these design tools developed further with After Work, in collaboration with artist and filmmaker Ben Rivers and poet Jay Bernard. This installation reflects on the relationship between work and free time, highlighting the hidden labour that underpins the culture of production (Condorelli, 2022).

The problem of controlling, predicting, the usage assigned to playground forms is central to her design. Condorelli’s position echoes the idea of an infrastructural architecture, which is also how she interprets the work of Lina Bo Bardi, “a real economy of means, making things in a way that they fulfil their function. Nothing else. No decoration, no frills, no extras” (Gratza, 2017).

The brutalist playground: Assemble collective with Simon Terrill

During the 60s in London, architects such as Alison and Peter Smithson, Powell & Moya, Ernö Goldinger, and Michael Brown marked British brutalist architecture by designing relevant housing estates. The public areas in between the buildings were designed to facilitate social encounters with playgrounds for children. Located in transition spaces, the playgrounds were realised with concrete and steel, with an experimental composition that reflected the brutalist aesthetics used in buildings. Later, brutalist playgrounds became a recognisable feature in the city, ultimately inspiring the contemporary art scene. Assemble, a collective working across architecture, design and art, and the artist Simon Terrill, both based in London, tackled the imagery associated with brutalist playgrounds (Figure 6). In their view, brutalist structures “were defined as much by what surrounded them, the open spaces, walkways, ramps, service areas playgrounds, as the structure themselves” (Terrill, 2015b). Together, they designed an immersive installation for the Architecture Gallery at the RIBA - Royal Institute of British Architects. They focused on interpreting the playgrounds of the Churchill Gardens complex in Pimlico, the Brownfield Estate in Poplar, and the Brunel Estate in Paddington (Assemble, 2015). For the installation, the playground, originally part of the architectural configuration of the liminal spaces between the residential towers, was selected and isolated, creating a series of play equipment to be reimagined by the users. The rough exposed concrete, a key feature of brutalism, was replaced by colourful foam whose texture recalled the original material but with totally different weight and consistency (Terrill, 2015a). The materiality shift aimed to “allow people to consider their formal characteristics separately from their materiality, and in doing so allow them to be reappraised as places for play” (Assemble, 2015). The installation was complemented by the film by Simon Terrill, including images of the estates sourced from the RIBA’s archive in contrast with the soft and pastel colour installation.

Assemble have further elaborated on the adventure playground in their Baltic Street Adventure Playground (2014) in a similar vein to what we have seen with Lady Allen and Riccardo Dalisi. It was initiated as a public art commission in Dalmarnock, East Glasgow. Children were encouraged to self-manage their space, up to the formation of a project team and a management committee. Another project, Play KX (2018) in King’s Cross, London, aimed at a similar behavioural freedom enhanced with loose parts that can be moved around. Assemble’s works transform playgrounds in performative installations, providing the users tools to explore their imaginative potential.

Drawing by the authors. Based on a photo by Andy Stagg, 2021

Source: Figure 5 Céline Condorelli, Tools for Imagination

Conclusions

The case studies presented above show different approaches to the design of playgrounds in-between residential buildings. On one hand, it was a field of experimentation for early participatory practices, in which the laboratories became meeting places for the local actors; on the other hand, it created its own playground aesthetics where forms triggered a wide gamut of affordances. What these experiences have in common is the creation of an open-ended system instead of a fixed project to be implemented. Their laboratory dimension established a methodology of constant experimentation with the community: while today it seems a likely condition for public projects, at the time of CIAM such attention to small-scale interventions was quite radical. Van Eyck playgrounds evolved in a “semi-hierarchical, semi-anarchic, highly participatory process, […] interrelating a mass of agents” (Lefaivre & de Roode, 2002, p. 45), involving both the citizens and departments of the municipality. Lady Allen’s initiatives targeted specific bombed sites, but acquired a symbolic stance that resonated nationally and influenced policy makers. Dalisi intentionally targeted chaos as governing agency for his workshops in Naples. All designs inevitably implied a fleeting character, a short-lived radical experience in which people meet and share an idea around the well-being of children. We have seen how transition spaces in housing complexes are the ideal location to strategise moderate-risk landscapes for local youngsters in a semi-controlled environment. The concept of in-between became a crucial aspect in such non-hierarchical compositions because of the lack of a centre, the existence of many autonomous elements, which shifted the attention to reciprocal relations within a distributed network. Dalisi recognised that an object’s capacity to establish relations is “in between, a bridge between two facts, through a void, which cannot be known” (Dalisi, 1967, p. 24). All projects are small interventions located in the periphery that nevertheless echoed across the country calling for policy changes and attention to public housing complexes. Dalisi proved that the didactic value of this design topic could be extended to students of Architecture schools, allowing them to keep contact with future users who are on the receiving end of the transformation. So, can we learn from these post-war experiences and revitalise the design of outdoor playground? In our view, a new design approach to playgrounds can be developed today through Living Labs as an ideal evolution of participatory practices through creative processes. Namely, ecosystems for the participation of the stakeholders (industry, societal actors, policy, academia, environment) in artistic activities with iterative cycles of analysis and synthesis. Following the structure that is generally presented in literature, an ideal scenario for the design of a participated playground would be split in three building blocks: exploration-current state vs. future state; experimentation-real life testing; evaluation-impact of the experiment (Cerreta & Panaro, 2017; Guzmán, del Carpio, Colomo-Palacios, & de Diego, 2013). This is also consistent with the process that is performed in each case study, eventually evaluated through reports (i.e., yearly reports of Lollard Street and Clydesdale Road or Dalisi’s course booklets). Then they transferred the lessons learnt to the following project. At an institutional level, in 2006, the European Commission funded the first two projects (CoreLabs and Clocks) based on Living Labs, before forming the European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL) that today includes 460+ labs. The initiative Urban Europe, launched by the European Commission in 2008, is the main funding agency for Living Labs. Also, the recent New European Bauhaus has been designed to link the European Green Deal to living spaces with “innovative solutions to complex societal problems together through co-creation” (European Commission, 2021). While Urban Living Labs are increasingly being experimented with across Europe, and the social turn of artistic practice emerged already in the first half of the 20th century (Bishop, 2006), new projects such as Condorelli’s and Assemble’s demonstrate that it is possible to merge artistic installations with playground design, with a view on regular implementation for collaborative governance of the territory. Also, there is a sufficiently strong networking background already in place that can connect best practices around the world. This idea is being developed by Helguera (2011), who introduced the concept of socially engaged arts as a form of dialogue around social issues. Dialogue, in turn, generates collective knowledge at the intersection between practice and academic research, extending place-making entitlements to local actors. Group Ludic were particularly successful in crossing artistic instances with civic engagement.

Hence, circling back to Dalisi’s idea of “aesthetic operator”, we propose that future developments in playground design can be ascribed to artistic practice-based research. Skains (2018) claims the importance of the figure of a practitioner-researcher to manage such complex processes in contested environments. This would resemble any of the four cases that we have mentioned above: playgrounds were not inventions of one designer, but often created by children themselves empowered with tools and coordination. It is essential for the artist-researcher to be immersed in the field, participate actively in the activities, interact with local community actors, and embrace inductive reasoning. In this way, principles of collaborative design employed by Lady Allen and Riccardo Dalisi can be combined with research on forms conducted by Aldo van Eyck and Group Ludic. Playgrounds are interactive spaces that allow modifications, that have the potential to establish a participatory environment.

As a consequence of widespread adoption of electronic devices for entertainment, play and physical activity have parted ways (Frost, 2010). Children don’t play anymore outdoors. Although playgrounds are disappearing, absorbed in shopping malls, open-air Living Labs in social housing complexes can be the engine to re-activate spaces of transition as magic realms. When the process of creation, realisation, and maintenance is shared, the playground becomes a meeting place. Adventure playgrounds alleviated the scars of bombed sites; Traiano workshops showed alternative ways of self-empowerment; Amsterdam set an example on the importance of small-scale interventions; and Group Ludic’s modules departed from the toughest neighbourhoods to test how social practices are negotiated. None of the above departed from a form, but rather from a field of affordances provided by a process of participation.

Future research is needed to assess the compatibility between Living Labs models and playground design, building on the reciprocal assonances that we have highlighted in this text. As it was in the spirit of post-war projects, and is in the prerogatives of Living Labs, the review of on-field activities should be as important as the design phase in order to encourage iterative improvement and replicability. Only then, successful experimentations will lead to new policies that in turn will give playground instances relevance in the public discourse.