Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista Portuguesa de Medicina Geral e Familiar

versão impressa ISSN 2182-5173

Rev Port Med Geral Fam vol.31 no.6 Lisboa dez. 2015

ESTUDOS ORIGINAIS

Attitudes of family medicine residents towards patients with alcohol-related problems

Atitudes dos internos de medicina geral e familiar para com os doentes com problemas ligados ao álcool

Gui Santos,* Frederico Rosário**

*Family medicine resident. Villa Longa Family Health Unit

**Family physician. Tomaz Ribeiro Primary Health Care Centre

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

ABSTRACT

Objective: To evaluate attitudes of family medicine residents to patients with alcohol-related problems.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Participants: Family medicine residents registered in the Family Medicine Residency Program in Lisbon.

Methods: Attitudes to patients with alcohol-related problems were assessed using the Short Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Perception Questionnaire. Associations were tested between questionnaire scores, gender and postgraduate training year.

Results: One hundred and ninety five residents meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria answered the questionnaire. Residents were on average 29.2 years old, and 74.4% were female. Residents felt secure in working with at-risk drinkers (88.7% scored above the Role Security scale midpoint) but reported lower levels of therapeutic commitment (57.9% scored above the scale midpoint). Although residents showed on average positive attitudes, they considered working with patients with alcohol-related problems an unpleasant task. Male and female residents reported similar attitudes towards these patients in all questionnaire domains (all p>0.05), and their attitudes remained unchanged throughout training (all p>0.05).

Conclusions: Residency training does not change residents’ attitudes to patients with excessive alcohol consumption. Inclusion of alcohol specific training modules into the residency program that take residents’ attitudes into account may help to improve residents’ willingness to counsel problem drinkers to reduce alcohol consumption.

RESUMO

Objectivos: Avaliar as atitudes dos internos de medicina geral e familiar para com os doentes com problemas ligados ao álcool.

Tipo de estudo: Estudo transversal.

População: Internos de medicina geral e familiar registados na Coordenação de Internato de Medicina Geral e Familiar de Lisboa e Vale do Tejo.

Métodos: As atitudes dos internos foram avaliadas usando o Short Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Perception Questionnaire. Foram investigadas associações entre os resultados do questionário, o género e o ano de internato.

Resultados: Cento e noventa e cinco internos, cumprindo critérios de inclusão e exclusão, responderam ao questionário. A idade média dos internos era de 29,2 anos e 74,4% eram do sexo feminino. Os internos consideraram sentir-se seguros para abordar doentes com consumo excessivo de álcool (88,7% tiveram resultados acima do ponto médio da escala Segurança), tendo, contudo, apresentado níveis mais baixos no Compromisso Terapêutico (57,9% tiveram resultados acima do ponto médio da escala). Apesar de terem, em média, atitudes positivas, os internos consideraram que trabalhar com estes doentes era uma tarefa desagradável, dado que apenas 22,6% pontuaram acima do ponto médio da escala Satisfação. As atitudes para com os doentes com consumo excessivo de álcool foram semelhantes em ambos os sexos (p>0,05), não se tendo igualmente observado diferenças nas atitudes com o ano de internato (p>0,05).

Conclusões: As atitudes dos internos de medicina geral e familiar para com os doentes com consumo excessivo de álcool mantêm-se inalteradas durante o processo de especialização. A inclusão de módulos de treino durante o internato na abordagem a esta problemática, e que tenham em conta as atitudes dos internos, poderão aumentar a sua motivação para abordar estes doentes.

Introduction

Alcohol consumption is a major public health problem. It ranks second among all causes of substance abuse-related disease, and fifth among all modifiable risk factors. It is a more important risk factor for disease than high body-mass index, high fasting plasma glucose or high total cholesterol.1

In Portugal, the prevalence of alcohol consumption is higher than that of any other addictive substance.2 Despite this, it remains largely unnoticed, masked by cultural acceptance and misinformation.

Alcohol-related problems are usually associated with dependency. However, the majority of these problems occur in those who are not alcohol dependent, but drink above recommended levels (two standard drinks a day for men, one for women). These drinking patterns are termed hazardous and harmful drinking. They may affect up to 30% of patients on a family physician’s adult patient list, while alcohol dependency affects only 2% to 5%.3-6

Family physicians occupy a strategic position in the primary care structure, which allows them to combat and reduce alcohol consumption. They recognize alcohol as an important risk factor and have at their disposal highly cost-effective techniques to address alcohol-related problems.7-9

Collectively known as alcohol screening and motivational-based brief interventions, these techniques are among the most effective in a physician’s therapeutic arsenal (Number Needed to Treat=8).10-11 However, a significant number of family physicians remain unwilling to integrate these countermeasures in routine clinical practice, despite considerable efforts deployed to this end.10,12-14

When asked about this contradiction, family physicians mention lack of training as an important barrier in addressing alcohol consumption with their patients.10,15 However, even with training, alcohol screening and brief intervention rates remain low. Evidence shows that some physicians benefit more than others from training, depending on their attitudes towards problem drinkers. Physicians with positive attitudes benefit from training and increase their brief intervention rates, whereas those with negative attitudes remain unengaged. This suggests that alcohol training programs need to take physicians’ attitudes into account.16

Family medicine residents are in a knowledge acquisition and skills development process and represent an ideal target for education and training in dealing with alcohol-related problems. Despite this, we know very little about attitudes of family medicine residents in dealing with problem drinkers, especially given the influence of attitudes in the effectiveness of training.7,12,16-18 With training, these future family physicians have the knowledge, skills, and commitment needed to address alcohol-related problems.

In this study we aimed to evaluate attitudes of family medicine residents towards patients with alcohol-related problems. It is our intention to determine if residency training changes residents’ attitudes towards these patients. We hypothesize that residency training improves residents’ attitudes, making them feel more secure and therapeutically committed to manage patients with alcohol-related problems.

Methods

Population and sample

All family medicine residents in Lisbon with a working e-mail address were invited to participate.

Residents who obtained their medical degree outside Portugal were excluded to ensure that possible differences in attitudes towards patients with alcohol-related problems were unrelated to prior medical training.

Study type

Cross-sectional study.

Data collection

Residents’ e-mail addresses were obtained from the Family Medicine Residency Program database. An e-mail was sent to each resident, describing the purpose of the study, and containing a link to the online questionnaire. Residents were asked to fill in the questionnaire through a computer interface—Google Drive Form. Answers were automatically recorded upon questionnaire completion between September 15 and October 15, 2014.

To increase participation, two e-mail reminders were sent encouraging questionnaire completion.

Measures

Residents were asked to report on demographics (age, sex, and postgraduate training year) and on their attitudes towards patients with alcohol-related problems. The latter was measured with the Short Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Perception Questionnaire (SAAPPQ), a validated instrument based on factor analysis of the original Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Perception Questionnaire.6,19 It asks physicians to express agreement on a seven-point Likert scale (ranked from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’) with ten statements regarding hazardous or harmful drinkers:

1. I feel I know enough about the causes of drinking problems to carry out my role when working with drinkers.

2. I feel I can appropriately advise my patients about drinking and its effects.

3. I feel I do not have much to be proud of when working with drinkers.

4. All in all I am inclined to feel I am a failure with drinkers.

5. I want to work with drinkers.

6. Pessimism is the most realistic attitude to take toward drinkers.

7. I feel I have the right to ask patients questions about their drinking when necessary.

8. I feel that my patients believe I have the right to ask them questions about drinking when necessary.

9. In general, it is rewarding to work with drinkers.

10. In general, I like drinkers.

Items are summed in pairs, each one measuring a subscale: Adequacy (statements 1 and 2), Self-esteem (statements 3 and 4), Motivation (statements 5 and 6), Legitimacy (statements 7 and 8), and Satisfaction (statements 9 and 10).

The two Self-esteem items (statements 3 and 4) and the second Motivation item (statement 6) were reverse scored since they are phrased in the semantically opposite direction.

These subscales are the expression of the latent factors Role Security (Adequacy and Legitimacy) and Therapeutic Commitment (Self-esteem, Motivation, and Satisfaction). The latent factors are measured adding the scores of the respective subscales.

Informed consent

The questionnaire included an introduction to the study and stated its objectives. Anonymity was ensured. No personal data that could identify the subjects were collected. The only personal data collected were age, gender and postgraduate training year. Participants were informed that by filling in the questionnaire they were accepting to participate in the study.

Confidentiality

Participants answered the online questionnaire wi-thout the presence of the investigators. Confidentiality was assured regarding all data collected.

Ethical approvals

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Regional Health Administration of Lisbon and Tagus Valley on July 25, 2014, Proc. 058/CES/INV/2014. Data collection was approved by the National Data Protection Committee.

Data analysis

Results are expressed as mean (plus and minus the standard deviation) or as a frequency distribution as appropriate. Residents’ attitudes are described for the whole sample as well as for each postgraduate training year.

Association between gender and postgraduate training year was tested with Pearson’s c2 test. Differences between ages across genders were tested with an independent samples t-test. Association between attitudes and gender was tested with the Mann-Whitney test. Association between attitudes and postgraduate training was tested with Kruskal-Wallis test. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was used as the cut-off point for significance. Analysis was conducted using R© 3.0.2 (2013 The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Sample characteristics

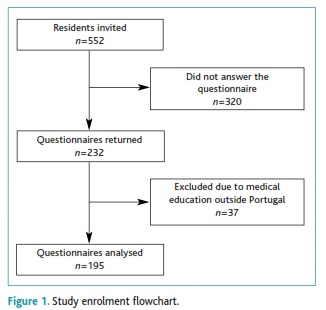

Two hundred and thirty two out of 552 (42.0%) residents completed the questionnaire (Figure 1). We excluded 37 (15.9%) residents because they received their medical education outside Portugal. The final sample (n=195) was 29.2±4.9 years old ranging from 25 years to 55 years, and most residents were female (74.4%). Seventy two (36.9%) residents were in the first postgraduate training year, 41 (21.0%) in the second, 43 (22.1%) in the third and 39 (20.0%) in the fourth. No differences were found between male and female residents concerning age and postgraduate training year (all p>0.05).

Residents’ attitudes towards patients with excessive alcohol consumption

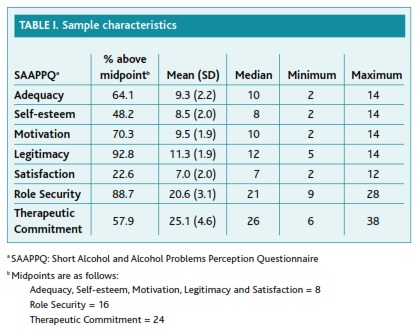

With the exception of Satisfaction, residents’ attitudes were on average above the midpoint of SAAPPQ’s scales (Table I). Residents felt secure in working with patients with excessive alcohol consumption, since 88.7% of them scored above the midpoint of Role Security. They regarded managing patients with alcohol-related problems as a legitimate part of their job, and considered they had acceptable knowledge and skill levels to perform this task. When compared to Role Security, residents reported lower Therapeutic Commitment in working with patients with excessive alcohol consumption, since only 57.9% scored above the midpoint of the scale (Table I). Although fairly motivated to work with hazardous or harmful drinkers, they expressed neutral feelings about their self--esteem when performing this specific task. Residents considered managing patients with excessive alcohol consumption a somewhat unpleasant experience, since only 22.6% reported a positive score on the Satisfaction sub-scale. Male and female residents reported similar attitudes towards these patients in all the SAAPPQ’ domains (Mann-Whitney test, all p>0.05).

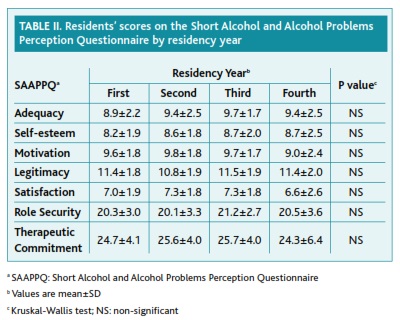

We also found similar results concerning residents’ attitudes between postgraduate training years (Table II), suggesting that attitudes remain unchanged throughout training (Kruskal-Wallis test, all p>0.05).

Discussion

This study found that residents’ attitudes towards patients with alcohol-related problems remain unchanged throughout training. We expected to observe some improvement during the four training years, given the progressive acquisition of knowledge, skills and experience in clinical practice. However, residents seem to reach the end of their training period with the same attitudes they have in the beginning. Evidence suggests that residents receive insufficient training in dealing with patients with excessive alcohol consumption,20 which may explain our findings. Having this in mind, we propose that delivering an alcohol training program that takes residents’ attitudes into account may improve feelings of security and commitment to work with hazardous and harmful drinkers, leading to an improvement in alcohol screening and brief intervention rates. This claim finds support in successful programs seeking to improve residents’ engagement with patients with alcohol-related problems. Adding alcohol-specific training modules to the residency program seems to improve residents’ knowledge and attitudes towards these patients, as well as their intervention rates.10,15,20-21 Besides addressing attitudes, other training components show promising results such as increasing opportunities to engage with drinkers,22 feedback and coaching using an Objective Structured Clinical Examination format,15 and use of validated screening tools.10 Additional research is needed to establish how residency training addresses alcohol-related problems and how we can improve training.

Residents reported feeling more secure than committed in working with hazardous and harmful drinkers. They considered addressing patients’ alcohol habits an integral part of the family physicians job, and felt they have the necessary knowledge and skills to approach them. However, their willingness to actually engage with hazardous and harmful drinkers seems to fall behind their sense of security. This finding is supported by previous studies concerning general practitioners’ attitudes towards patients with alcohol-related problems. Geirsson et al. found that Swedish general practitioners had positive attitudes concerning legitimacy and adequacy towards working with problem drinkers but lacked motivation, satisfaction, and task-specific self-esteem in doing it. These authors also considered physicians’ lack of training as a major obstacle to improving care of patients with problem drinking.23 Wilson et al. found a similar pattern among English general practitioners. Eighty seven percent of these professionals agreed that this task was a legitimate part of their work, and 78% felt they had enough knowledge and skills. On the other hand, only 53% reported high self-esteem levels, 42% felt motivated, and 15% agreed they felt satisfaction in working with hazardous and harmful drinkers.18 The ODHIN—Optimizing Delivery of Health Care Interventions—study (in which 234 Portuguese family physicians participated) showed that 92% of all general practitioners felt secure but only 46% considered being therapeutically committed.24 This similarity in attitudes between family medicine residents and family physicians suggests that attitudes towards patients with alcohol-related problems remain unchanged even after residency training ends. The reasons for this are unclear but one possible explanation may relate to the lack of training in alcohol-related problems in continuing medical education. Additional research is needed to explain this finding.

The results from this study, supported by the results from other studies, suggest that to improve screening and counselling rates we must address physicians’ emotional responses, especially concerning attitudes related to their therapeutic commitment. We hypothesize that including alcohol-specific training modules into the residency training program that take residents’ emotions into account will increase their willingness to work with drinkers, setting the stage for an improvement in screening and counselling rates. We also wonder if residents’ self-perception of their knowledge and skills match their real capabilities. Training on coping with alcohol-related problems is rare in residency training, and is seldom addressed in medical schools. Results from other studies show that most physicians think medical school training leaves doctors unprepared to work with problem drinkers,25 that they are unaware of daily drinking limits,26-27 and that they have no knowledge of validated screening tools to identify drinkers.12,27-28 Since physicians show reluctance to admit their own lack of knowledge and skills concerning alcohol-related problems,29 we believe residents may have overrated their adequacy levels. If this is true, then we need to include training modules in the residency program that address knowledge, skills and attitudes towards working with patients with excessive alcohol consumption.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use a validated instrument to determine the attitudes of family medicine residents’ in Portugal towards patients with excessive alcohol consumption. We believe the me-thods and results from this study can help in the design of future studies aiming to clarify the relation between residency training and residents’ attitudes towards problem drinkers. The results from this study may also help to design new alcohol-related training modules (or improve existing ones) tailored to residents’ attitudes. Nevertheless, we recognize the existence of some caveats that need to be kept in mind when interpreting these results. First, we only surveyed residents from one Family Medicine Residency Program. This sample may not be representative of all Portuguese family medicine residents. Second, we obtained a low response rate to our survey. This may also affect representativeness since it is conceivable that residents with a higher interest in alcohol-related problems were more likely to respond to the survey. Third, residents who completed the questionnaire may have higher motivation towards this subject than those who did not, which means their views may not represent the views of those who chose not to answer. Finally, we did not evaluate the residency program to determine the existence of specific alcohol training modules, meaning that it is not possible to relate attitudes to training.

Further investigation on this matter is needed to determine the views of residents from other Family Medicine Residency Programs, and to relate them with possible differences in residency training programs.

Conclusions

Attitudes of family medicine residents to patients with excessive alcohol consumption remain unchanged as they go through residency training. Inclusion of alcohol specific training modules into the residency program that take the attitudes of residents into account may help to improve their willingness to engage with patients with alcohol-related problems.

REFERENCES

1. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224-60. [ Links ]

2. Balsa C, Vital C, Urbano C. III Inquérito nacional ao consumo de substâncias psicoativas na população portuguesa: relatório preliminar. Lisboa: SICAD; 2013. [ Links ]

3. Friedmann PD. Alcohol use in adults. N Eng J Med. 2013;368(4):365-73. [ Links ]

4. Saitz R. Alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care: absence of evidence for efficacy in people with dependence or very heavy drinking. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(6):631-40. [ Links ]

5. Anderson P, Laurant M, Kaner E, Wensing M, Grol R. Engaging general practitioners in the management of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption: results of a meta-analysis. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65(2):191-9. [ Links ]

6. Ribeiro C. A medicina geral e familiar e a abordagem do consumo de álcool: detecção e intervenções breves no âmbito dos cuidados de saúde primários (The family medicine approach to alcohol consumption: detection and brief interventions in Primary Health Care). Acta Med Port. 2011;24(S2):355-68. Portuguese

7. Wojnar M. Optimizing Delivery of Health Care Interventions (ODHIN): survey of attitudes and managing alcohol problems in general practice in Europe - final report. Warsaw: Medical University of Warsaw; 2014. [ Links ]

8. Anderson P, Cremona A, Paton A, Turner C, Wallace P. The risk of alcohol. Addiction. 1993;88(11):1493-508. [ Links ]

9. Moyer A, Finney JW, Swearingen CE, Vergun P. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a meta-analytic review of controlled investigations in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations. Addiction. 2002;97(3):279-92. [ Links ]

10. Pringle JL, Kowalchuk A, Meyers JA, Seale JP. Equipping residents to address alcohol and drug abuse: the National SBIRT Residency Training Project. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(1):58-63. [ Links ]

11. Anderson P, Gual A, Colom J. Alcohol and primary health care: clinical guidelines on identification and brief interventions. Barcelona: Department of Health of the Government of Catalonia; 2005. [ Links ]

12. Aalto M, Pekuri P, Seppä K. Primary health care nurses' and physicians' attitudes, knowledge and beliefs regarding brief intervention for heavy drinkers. Addiction. 2001;96(2):305-11. [ Links ]

13. Rumpf HJ, Bohlmann J, Hill A, Hapke U, John U. Physicians' low detection rates of alcohol dependence or abuse: a matter of methodological shortcomings? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(3):133-7. [ Links ]

14. O'Donnell A, Anderson P, Newbury-Birch D, Schulte B, Schmidt C, Reimer J, et al. The impact of brief alcohol interventions in primary healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49(1):66-78. [ Links ]

15. Cole B, Clark DC, Seale JP, Shellenberger S, Lyme A, Johnson JA, et al. Reinventing the reel: an innovative approach to resident skill-building in motivational interviewing for brief intervention. Subst Abus. 2012;33(3):278-81. [ Links ]

16. Anderson P, Kaner E, Wutzke S, Funk M, Heather N, Wensing M, et al. Attitudes and managing alcohol problems in general practice: an interaction analysis based on findings from a WHO collaborative study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39(4):351-6. [ Links ]

17. Deehan A, Marshall EJ, Strang J. Tackling alcohol misuse: opportunities and obstacles in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48(436):1779-82. [ Links ]

18. Wilson GB, Lock CA, Heather N, Cassidy P, Christie MM, Kaner EF. Intervention against excessive alcohol consumption in primary health care: a survey of GPs' attitudes and practices in England 10 years on. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(5):570-7. [ Links ]

19. Anderson P, Clement S. The AAPPQ revisited: the measurement of general practitioners' attitudes to alcohol problems. Br J Addict. 1987;82(7):753-9. [ Links ]

20. Foley ME, Garland E, Stimmel B, Merino R. Innovative clinical addiction research training track in preventive medicine. Subst Abus. 2000;21(2):111-9. [ Links ]

21. Seale JP, Shellenberger S, Boltri JM, Okosun IS, Barton B. Effects of screening and brief intervention training on resident and faculty alcohol intervention behaviours: a pre- post-intervention assessment. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6:46. [ Links ]

22. Schorling JB, Klas PT, Willems JP, Everett AS. Addressing alcohol use among primary care patients: differences between family medicine and internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9(5):248-54. [ Links ]

23. Geirsson M, Bendtsen P, Spak F. Attitudes of Swedish general practitioners and nurses working with lifestyle change, with special reference to alcohol consumption. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40(5):388-93. [ Links ]

24. Anderson P, Wojnar M, Jakubczyk A, Gual A, Reynolds J, Segura L, et al. Managing alcohol problems in general practice in Europe: results from the European ODHIN survey of general practitioners. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49(5):531-9. [ Links ]

25. Roche AM, Guray C, Saunders JB. General practitioners' experiences of patients with drug and alcohol problems. Br J Addict. 1991;86(3):263-75. [ Links ]

26. Roche AM, Richard GP. Doctors' willingness to intervene in patients' drug and alcohol problems. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(9):1053-61. [ Links ]

27. Akvardar Y, Uçku R, Unal B, Günay T, Akdede BB, Ergör G, et al. Pratisyen Hekimler Alkol Kullanım Sorunları Olan Hastaları Tanıyor ve Tedavi Ediyorlar Mı? (Do general practitioners diagnose and treat patients with alcohol use problems?). Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2010;21(1):5-13. Turkish

28. Nygaard P, Paschall MJ, Aasland OG, Lund KE. Use and barriers to use of screening and brief interventions for alcohol problems among Norwegian general practitioners. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45(2):207-12. [ Links ]

29. Miller NS, Sheppard LM, Colenda CC, Magen J. Why physicians are unprepared to treat patients who have alcohol- and drug-related disorders. Acad Med. 2001;76(5):410-8. [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

Gui Santos

Av. D. João II, Lote 4.47.01, Bloco A, 1º D

1990-098 Lisboa - PORTUGAL

E-mail: guimms85@gmail.com

Conflict of interests

Frederico Rosário is an invited reviewer of this journal and declares he was not involved in the editorial decision process for this paper.

The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approvals

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Regional Health Administration of Lisbon and Tagus Valley on July 25, 2014, Proc.058/CES/INV/2014. Data collection was approved by the National Data Protection Committee.

Recebido em 16-06-2015

Aceite para publicação em 23-11-2015