Background

Benzodiazepines (BZD) are extensively used to treat anxiety, and sleep disorders and as muscle relaxants.1-2 BZD continuous utilization has been strongly associated with an increased number of falls and bone fractures, (3-5 a higher number of road accidents, (4,6 and possible role in inducing the phenomenon of suicide. (7-9 Although with weaker evidence, BZD use has also been related to cognitive decline and dementia10-12 and increased mortality risk. (13 Although national and international clinical guidelines recommend limiting the duration of BZD treatment to only a few weeks, the prevalence of long-term use remains widespread.

In 2015, Portugal was the OECD country with the highest reported consumption of BZD, with 114 defined daily doses per 1,000 inhabitants (DHD) in 2015 versus 87 DHD in Spain and 16 DHD in the United Kingdom. In this same year, it was reported that there were 1.9 million users who received at least one BZD prescription or similar. (14 The most recent data published by the Portuguese National Authority of Medicines and Health Products (INFARMED) reported that anxiolytics, sedatives, and hypnotics were the fourth most used therapeutic class, with over 10 million packages sold in 2019. (15 BZD’ users were mostly female (70%), aged between 55 and 79 years old, and the proportion of the Portuguese population that used these drugs increased with age, corresponding to more than half of the residents in Portugal of female gender aged 85 or over. (14

The excessive BZD prescription pattern has long been recognised as a public health concern, and many interventions using multiple strategies have been implemented to reduce the extent of BZD usage. Simple interventions include minimal educational interventions, (16-18 audits, feedback interventions, (19 and policy interventions. (20-21 More complex interventions include tailored systematic discontinuation interventions. (22-25 Results from previous studies are varied and usually small, with loss of effect after a short-term period.

Since approximately 80% of BZD prescriptions are issued by general practitioners (GPs), (14 changing prescription patterns in the primary health care setting should be a priority.

GPs have limited time for consultations with each patient and often encounters difficulties in managing withdrawal. A recent study published in Portugal concerning physicians’ beliefs and attitudes about BZD collected data from a self-administered online questionnaire comprising four different sections: general beliefs about BZD; attitudes about prescription and chronic use of BZD; self-perception of literacy about BZD; and self-efficacy perceptions in promoting withdrawal. (26 The study concluded that despite the physician’s adequate awareness about the risks of chronic BZD use is adequate, they continuously prescribe excessive amounts of these drugs to excess. Therefore, efforts should be made to develop feasible, evidence-based, effective, and expeditious interventions that can be easily implemented in primary care settings. (27

This study assessed the efficacy of a Digital Behaviour Change Intervention (DBCI) online platform - named ePrimaPrescribe - to change the BZD prescription patterns. Secondarily we aimed to determine if the ePrimaPrescribe online program was associated with a change in diagnoses registration and to perform a cost analysis for the National Health Service expenditure with BZD’s co-payment.

Methods

We followed CONSORT guidelines for the analysis of cluster-randomized trials and for the presentation of our results.

Trial design and setting

We chose to perform a non-blind, cluster-randomised controlled trial.

We chose a cluster design aiming to reduce potential contamination of the intervention between trial arms and prevent the effects of the training influencing untrained GPs.

The setting for our intervention was primary health care units in a rural region in Portugal, with an area of 7,393 km², an estimated population of 166,706 inhabitants (2011), a population density of 22.5 inhabit/km², and approximately 250 GPs working in primary health care units. Portugal has a public accessible national health service, but mental health indicators are alarming. (28 BZD prescription in Portugal is very high, as introduced in our background section, and the consumption of these drugs is particularly significant in the region where our intervention was implemented. (29

Participants

In Portugal, the National Health Service (NHS) distinguishes two types of primary care units. The default one is the ‘personalized care units’ model (UCSP), in which professionals receive a fixed salary. The other model is the ‘family health units’ (USF), which enjoy higher functional and organizational autonomy, (30 and where GPs might have a mixed payment scheme that includes salary, capitation, and pay for performance. (31 We included primary health care units from the two main existing types in Portugal - ‘personalized care units’ (UCSP); ‘family health units’ (USF), since different types of organizational characteristics were considered to possibly influence both intervention acceptability and GPs performance.

We considered eligible for inclusion GPs identified as being continuously prescribing BZD, using an online prescription tool that is available in all Portuguese NHS primary health care units during the period of analysis.

At the initial intervention onsite visit, a participant information sheet was distributed, and GPs were given the opportunity to ask questions about the study. The informed consent was subsequently distributed and signed both by the participants and the author.

Intervention

Our intervention was developed using as background the Behavioural Changing Wheel theoretical framework. (32 We chose to deliver our intervention as a Digital Behaviour Change Intervention (DBCI) (33 considering that an online platform, free and available at the user’s convenience, using education, persuasion, training, restriction, modelling, and enablement as intervention functions would increase its affordability, practicability, effectiveness, and acceptability.

The content of the ePrimaPrescribe DBCI was developed based on guidelines for anxiety and depression treatment and BZD withdrawal. Our primary sources of information were National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, (34 guidelines issued by the Portuguese National Health Directorate (DGS), (35-36 and other relevant literature specifically addressing deprescribing evidence-based practice guidelines. (37-38

The program comprised three e-learning modules, each with approximately 30 minutes of duration and with the following subjects: pharmacological effect and clinical use of BZD; how to treat anxiety disorder by avoiding the continuous use of BZD; how to manage BZD dependence and BZD withdrawal proposals.

We developed an alternative DBCI, ComunicaSaudeMental, that was delivered to GPs practicing at primary health care units included in the control intervention arm with similar module number and duration. The content of this platform focused on communication techniques for addressing light to moderate mental health disorders or patients’ emotional management in primary health care settings.

The program was delivered at an initial face-to-face onsite visit performed in every primary health care unit by a psychiatry specialist, with clinical practice in the same geographical area where the intervention occurred. A second face-to-face onsite visit was performed at the end of the intervention period (twelve months after implementation), to gather data concerning the implementation evaluation process, through questionnaires and in-depth interviews, which are described in the next sections. The study was implemented between May 2017 and June 2018.

GPs agreeing to participate, and after signing the informed consent, were given an individual password to access ePrimaPrescribe or alternatively the platform ComunicaSaudeMental, and an individual identification code which related anonymously to data gathered in interviews, questionnaires, and program utilisation.

The utilisation of the online platforms was evaluated in terms of a dichotomization of ‘access’ or ‘no access’ to the platform over the total period of the study.

An email was sent every three months to each GP as a reminder for participation.

Data collection

Data were directly extracted, delivered, and monitored by the Portuguese Shared Services of the Ministry of Health, and were detailed so each entry on the database corresponded to a prescription issued to an observed patient.

Outcomes were assessed for a period of twelve months before and after the intervention to investigate whether the ePrimaPrescribe online training was associated with a sustained change in BZD prescribing patterns.

The following variables were associated with each prescription: regarding the patient’s characteristics: random identification number (unique to each patient), age, sex, and diagnoses; regarding prescriber’s characteristics: random identification number (unique to each GP and associated with each prescription); regarding primary health care unit’s characteristics: name and unique identification code; type of primary health care unit (USF vs UCSP); regarding details concerning BZD and antidepressant prescription: year and month of each prescription, and cost for the National Health Service with BZD co-payment.

Sample size

Data collected from the previous research39 allowed performing estimation for sample size (SS) calculation. The SS calculation initially considered observation’s independence and an expected effect size of 20% reduction. We adjusted for the intra-cluster correlation coefficient to obtain a design effect with an 80% power.

Considering a 1:1 ratio of allocation of controls per intervention unit, an alpha type error of 0.05, a cluster size of five GPs per unit, and a minimal difference of 20% reduction in the number of BZD prescriptions, we obtained that the study would have to include seven clusters per study arm to have an 80% power.

Randomization

Units’ randomization was performed considering the following data: type of primary care unit (UCSP vs USF); the number of GPs per unit; average number of appointments and number of patients per unit per month, and the proximity of primary health care units. These characteristics were considered because it was expected that the unit’s similar organizational and performance characteristics would significantly influence our study results.

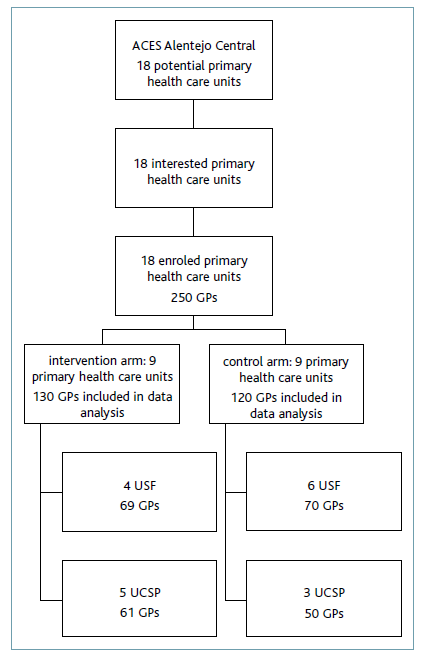

Regarding a total of eighteen potentially eligible primary health care units, all agreeing to participate in the study, and considering the referred characteristics, nine units were randomised for the intervention group (corresponding to a sample of fifty-eight doctors) and nine units were randomised for the control group (corresponding to a sample of fifty-two doctors) (additional file 1). We considered this sample fulfilled the criteria for significance and power for the study’s results.

Primary health care unit allocation was not blinded to the authors.

Non-blinding of the author was minimized by the fact that primary outcome data were directly extracted from the prescription database with coded data entry and blinding of the Shared Services of the Portuguese Ministry of Health data manager.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measure

We used as primary outcome measure the frequency of BZD prescriptions issued per month, the proportion of prescriptions issued by GPs included in intervention and control units over the study time frame, and more specifically at baseline, six and twelve months after the intervention.

We included BZD from the following Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system-coded groups: N05B; N05C and N03AE.

Secondary outcome measures

To study the effect of ePrimaprescribe on diagnoses registration, we used the monthly registration of psychological symptoms, complaints, and disorders, coded in the same month as BZD prescriptions. The GPs diagnosis registration used the International Classification of Primary Care, second edition (ICPC-2) developed and updated by the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) International Classification Committee (WICC).

We further performed a cost analysis considering the monthly National Health Service spending with BZD co-payment.

Statistical methods

Most analyses were performed at the level of intervention versus control clusters. Analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis (i.e., all initially enrolled GPs were included in the analysis according to the group to which they were assigned).

We performed an exploratory descriptive analysis using the number of prescriptions as the primary measure of outcome, considering as main influencing factors the patient’s age and sex, by units of intervention and control.

We tested for significant differences among the baseline characteristics of the intervention and control groups. We performed descriptive analysis, with continuous variables summarised using means and standard deviations for normal distributions, and by medians and the 25th and 75th percentiles for non-normal distributions.

Estimated effects were calculated by comparing the number of prescriptions in the intervention and control groups at baseline, six months, and twelve months after the intervention.

We tested for significant differences in the baseline characteristics of the control and intervention groups using t-tests or one-way ANOVA. These included the calculation of means and/or proportions with confidence intervals (Cis), and robust standard deviations (SDs) (to account for clustering).

We performed a secondary analysis where we explored the association between the frequency of BZD with diagnoses using Chi-Squared tests for testing independence in two-way contingency tables. The Cochran-Armitage trend test was employed to assess how the proportion of two ordinal successes varies across the levels of a binary variable. And when both variables in a contingency table had ordered categories, the linear-by-linear test was used instead. (40

We finally performed a cost analysis considering the monthly National Health Service spending with BZD co-payment, using t-tests or one-way ANOVA.

Statistical significance was considered for p-values < 0.05.

The R statistical software41-42 was used to perform all the statistical analyses within the RStudio integrated development environment for R, RStudio Team (2019). The graphs and plots were obtained with the use of the ggplot2 R package. (43

Results

Delivery of intervention and participant’s characteristics

All 18 eligible primary health care units agreed to participate in the study.

These 18 units were randomly allocated, considering specific matching characteristics as previously mentioned, to receive the DBCI ePrimaPrescribe online program or to receive the ComunicaSaudeMental online program containing basic information on care and communication skills with patients suffering from mild and moderate mental disorders.

Of the total 250 GPs whose prescriptions were analysed, 130 were included in the intervention group and 120 were included in the control group. Prescribers included in the intervention group were distributed by four USFs, with 69 GPs, and five UCSPs with 61 GPs. Prescribers included in the control group were distributed by six USFs, with 70 GPs, and three UCSPs with 50 GPs.

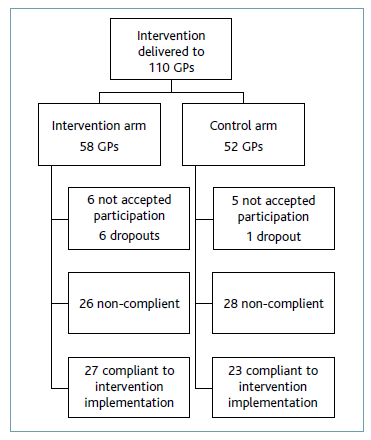

The intervention was then delivered to 110 GPs. Fifty-eight GPs prescribed at primary health care units allocated to the intervention group, and 52 GPs prescribed at primary health care units allocated to the control group. At the initial moment of implementation, six doctors in the intervention group and five doctors in the control group did not agree to participate. Throughout the study period, there were five dropouts in the intervention group (one due to death) and one dropout in the control group.

We assessed ePrimaPrescribe utilization through dichotomization of ‘access’ or ‘no access’ to the platform over the total period of the study. At units included in the intervention group, we verified that 27 doctors used the platform, therefore with a platform utilization rate of 57% of the total of 47 physicians who completed study participation. At units included in the control group, 23 physicians used the platform, hence with a platform utilization rate of 50% of the total of 46 physicians who completed study participation (additional file 2).

Primary outcomes

Characteristics of patients with BZD prescription

At baseline, patients’ average age was 67.3 years old in the intervention group and 67 years old in the control group. The age, either at intervention (p=0.383) or control group (p=0.269), did not change significantly at six and 12 months after the intervention, nor between the intervention and control group also not differ significantly (p=0.159) (Table 1).

When specifically addressing age categories, we found that BZD were more frequently prescribed to older patients both in the intervention and control groups. Twelve months after intervention implementation, the prescription increased (but not significantly p=0.164) for patients over 65 years old. The proportions of prescriptions for < 65 and > 65 does not seem to increase or decrease with time (p-value=0.184) (additional file 2).

BZD were more frequently prescribed to females, either at baseline (73.5%), six months (75.7%), or 12 months after intervention implementation (73.3%). The frequency of prescription to females did not change significantly at different points in time within and between the intervention and control groups (p=0.499). The proportions of prescriptions for males and females did not seem to increase or decrease with time when specifically testing for the intervention group (p=0.304) (additional file 2).

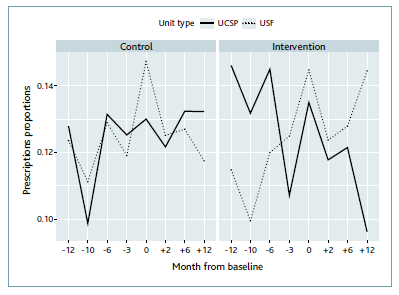

BZD prescription characteristics

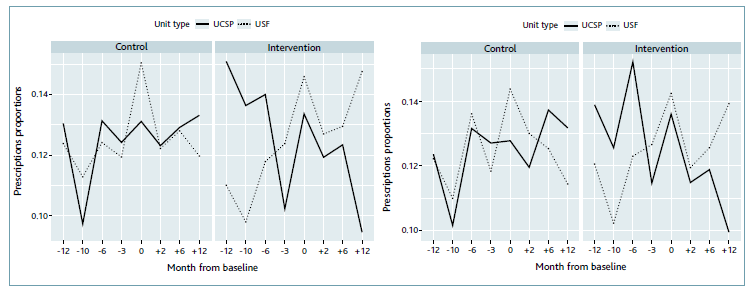

Concerning BZD prescription, we performed a comparative analysis by type of primary health care unit. This analysis showed that the proportions of prescriptions at USCP units included in the intervention group decreased significantly with time (the Cochran-Armitage test supports the trend hypothesis [p-value < 0.001]), and especially when compared with the proportion of prescriptions at UCSP included in the control group. The proportions of prescriptions at USF-type units included in the control group also decreased significantly with time (Cochran-Armitage test with a p-value < 0.001) (Figure 1).

A more specific analysis, comparing prescriptions to patients over and under 65 years old by type of primary health care unit, shows a slightly more pronounced decrease in the first six months after the intervention in younger users both at UCSP and USF unit types.

Regarding the most frequently prescribed BZD active pharmaceutical ingredients, alprazolam, was the most frequently prescribed drug, varying between 20.9% to 24.3%. Alprazolam prescription increased at 12 months after intervention implementation. We found that the distributions of the active pharmaceutical ingredients prescribed in the intervention group differed over time (Chi-square test of homogeneity p=0.025), which didn’t happen to prescriptions issued at units included in the control group (Chi-square test of homogeneity p=0.158) (Figure 2).

A more specific analysis, regarding prescription by active pharmaceutical ingredient to patients over 65 years old, shows that alprazolam was still the most frequently prescribed. The trend for midazolam prescription also did not change in this specific analysis.

Figure 3 Prescription proportion of BZDs at intervention and control units distributed by type of primary health care unit.

Figure 4 BZD prescription to patients over 65 years old compared with BZD prescription to patients under 65 years old.

When specifically considering prescription by active pharmaceutical ingredient to females, the prescription trend does not change over time, hence intervention implementation does not seem to have any effect on the prescription trend.

Regarding BZD prescription by drug half-life, it was verified that most prescribed BZD had a medium half-life, and the second most prescribed were BZD with a short half-life. After a linear-by-linear association test was applied we found there was no evidence of a significant change in prescription trend for BZD half-life with time in the intervention group (p=0.896).

Secondary outcomes

Diagnosis registration coded in the same month as the BZD prescription

To perform the following analysis, we used a database with all diagnoses that were coded during our study time frame.

The diagnoses included in this secondary analysis are detailed in additional file 8.

During the time of interest for our research (12 months before to 12 months after intervention implementation), 9,348 mental health complaints/diagnoses were coded to patients with BZD prescriptions.

Depressive disorder (P76) was the diagnosis more frequently coded both in the intervention and control groups, at baseline, six months after the intervention and 12 months after intervention (between 28.6 and 42.3% of the six most frequently coded diagnoses). It was followed by anxiety disorder/anxiety state (P74) (between 12.5 and 35.6% of the six most frequently coded diagnosis). Sleep disturbance (P06) was the third most frequent coded diagnosis (between 3.3 and 26.8% of the six most frequently coded diagnoses). Dementia (P70) was the fifth most frequently diagnosis coded in the same month as BZD prescription (between 4.3 and 20.6% of the six most frequently coded diagnoses). There is evidence that the distributions of the diagnosis differ over time, both in the intervention (p=0.007) and control groups (p=<0.001). We could not find a significant decrease in depressive disorder (P76), anxiety disorder/anxiety state (P74), sleep disturbance (P06), or dementia (P70) diagnosis, in the intervention group after intervention implementation.

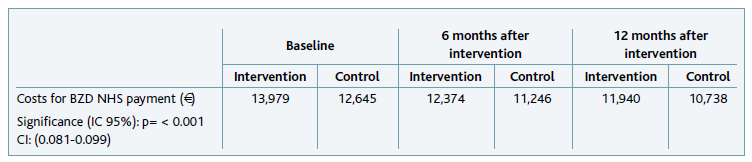

Costs for NHS with BZD’s co-payment

Concerning costs for the NHS with BZD’s co-payment, the total for the 18 units included in the study in each of the analysed months was over 23,000 €, meaning an average of approximately 1,300 € per unit per month. There was a significant difference between costs in the intervention and control groups (Welch Two Sample t-test with p<0.001), however, this difference might be attributed to the large number of prescriptions included in our database, since the actual value difference was less than 0.01 €. There was no significant change in the cost for NHS with BZD co-payment neither at intervention units (p=0.331) nor at control units (p=0.162) throughout the time the study occurred.

Discussion

Our study included the analysis of BZD prescription trends issued by all prescribing GPs in a region of Portugal for the period of twelve months before and after the implementation of a Digital Behaviour Change Intervention. In the literature, it is more common to find reports with data coming from BZD sales or consumption. (14-15 Notwithstanding, we chose to use prescription data as our main primary and secondary outcomes since our study aimed to specifically analyse the change in prescription trend. Also, in the specific case of BZD, due to its low price, effectiveness in immediate symptom relief, and high dependence potential, the figures for prescription and consumption are probably approximate.

Primary outcomes

BZD were prescribed more frequently to patients over sixty-five years old at baseline. We found a slight increase in prescription trends in patients over sixty-five years old after intervention implementation, although this trend change was not significant. We also found that the average age was over sixty-seven years old, both at baseline and twelve months after the intervention, and similar average age (sixty-seven years old) was found at control group. These findings are similar to what is found in other studies, (44-47 and can be explained by the higher prevalence of insomnia, anxiety disorders, and organic conditions elders present, together with a more frequent demand for medical attention. (45 BZD prescription should be avoided at older ages considering its secondary effects such as increased number of falls and bone fractures, (3-5 cognitive decline, and dementia. (10-12 These recommendations were highlighted in ePrimaPrescribe program modules’ content, hence we expected a positive effect coming from the program’s implementation, with a decrease in prescription, which was not observed. Our analysis comparing prescriptions to patients over and under sixty-five years old by primary health care unit type, showing a slight decrease in prescription frequency to younger patients in the first six months after the intervention, further suggests a greater difficulty in changing BZD prescriptions to older patients. The slight increase in prescription trend to patients over sixty-five years old, observed in primary health care units included in the intervention group, should be the target of worrisome consideration since it goes in the opposite sense of what was intended with our intervention.

BZD were more frequently prescribed to females at baseline, and twelve months after intervention implementation. We did not find any significant change in prescription trends either between different time points or between the intervention and control groups. The higher prescription to females that we found in our study agrees with previously published research. (44-45 There could be various explanations for this finding: most epidemiological studies in the community show a prevalence of psychiatric disorders which is two to three times higher in women than in men; (28,48 differences in access to the health system, since women tend to consult more frequently with their doctors than do men; differences in symptoms presentation since women might present anxiety and depressive disorders with complaints which are easier for GPs to interpret and identify; and different approaches from the health professional. (49

We performed a specific analysis that considered the effect of our intervention implementation by primary health care unit type. This analysis reported a significant decrease in the proportion of BZD prescribed at UCSPs included in the intervention group, but also a significant decrease in the USFs primary health care unit type included in the control group. Hence, despite it has been reported that primary health care unit organizations might influence prescription outcomes, (50 we did not find any significant difference in the prescription trend of UCSPs or USFs. We might hypothesize that these data are related to the fact that, in Portugal, the only performance indicator for USFs primary health care unit type, aiming to limit BZD prescription, is rarely contracted, hence there is no special incentive for GPs prescribing at USFs to behave differently than GPs prescribing at UCSPs.

We found that the most frequently prescribed active pharmaceutical ingredients - alprazolam, zolpidem, bromazepam, and diazepam - accounted for approximately half the total prescriptions, and this trend did not change with intervention implementation. The active pharmaceutical ingredients prescription frequency is in agreement with national and international reports. (15,45,51 We performed a specific analysis of the most frequently prescribed pharmaceutical ingredients prescribed to patients over sixty-five years old and alprazolam was still the most frequently prescribed. In this specific analysis, we also confirmed that midazolam, a BZD with a very short-acting half-life, is highly addictive, and for that reason advised to be avoided as outpatient prescription, especially to older patients, represented 3.6% of total prescriptions. Furthermore, our analysis of BZD prescription by BZD half-life demonstrated that BZD with a short-half life was the second most prescribed group, with a slight increase after intervention implementation. These findings, once again in the opposite sense of our intervention purpose, should be a matter of concern.

Secondary outcomes

Diagnosis registration

Our analysis concerning diagnosis registration in the same month of BZD prescription aimed to explore the association of the most frequently coded diagnosis to patients using BZD. The finding that depressive disorder was the diagnosis more frequently coded both in the intervention and control groups and that sleep disturbance and dementia were respectively the third and fifth most frequently coded diagnosis, despite a non-surprising result, should be considered with a high degree of concern. BZD prescription is not the recommended treatment for depressive disorder, however during the initial phases of antidepressant treatment, BZD are often prescribed as a coadjuvant if anxiety, agitation, and/or insomnia. Despite a previous study showing that about 30% of patients were initially prescribed BZD for a depressive disorder, (23 these patients should be treated with the BZD for no longer than two weeks to prevent the development of dependence, but, once initiated, BZD prescription is often maintained for longer. BZD prescription should be avoided in dementia due to its documented association with cognitive impairment and falls.

In Portugal, it is not mandatory to perform a diagnosis coding each time a GPs issues a prescription. The registration tool available in the Portuguese primary health care units allows GPs to code just once a certain diagnosis and keep it associated with the patient file, hence dismissing further need to repeat the diagnosis coding, no matter how long the treatment for that disorder is kept. Notwithstanding, our results concerning diagnosis coding agreed with the literature, suggesting that BZD prescriptions are often issued to inadequate clinical situations, and in agreement with our effectiveness trial results, showing the lack of effect from our intervention to change diagnosis identification.

Cost analysis

We finally performed a cost analysis regarding costs for the NHS with BZD’s co-payment, which showed no difference between intervention and control units, or any significant change through our intervention implementation time frame. In the region where our study was implemented, in 2021, there were only eight psychologists working full-time and three others workings part-time in the total eighteen units included in our study. Despite the suspension of BZD co-payment did not show a significant positive impact on BZD prescription in other countries, (20 the saving coming from this suspension could contribute to improving the access and quality of care in the Portuguese primary health care setting. For instance, we verified that the suspension of co-payment in Portugal would represent a monthly saving of around 23,000 €, which would be enough to hire at least one psychologist for each unit in the intervention region.

Strengths and limitations

Most published studies concerning interventions to improve the prescription of BZD rely upon voluntary participation, often resulting in the participation of GPs who prescribe BZD more rationally52 or are especially motivated to change their prescription pattern. Although our study relied on GPs’ voluntary participation, since the program was presented and accepted by all unit coordinators, most GPs prescribing in the region were included. The large patient sample size and a large number of participating GPs, together with the small average cluster size, provided this study with sufficient power to detect small differences between groups, contributing to the quality of our data.

We recognize the potential influence of a very significant number of non-compliant GPs on platform utilization. From the total prescribing GPs considered in our analysis, 103 were included in the intervention group, and 97 were included in the control group, a significant number did not use the platform, corresponding to 79% of the total number of GPs included in the intervention group and 80% of the total number of GPs included in the control group. Despite this fact, no change in the design of the study was performed, considering the importance of maintaining the methodological coherence selected (cluster randomization), and the probable contamination of GPs who did not access the platform by those who did (therefore their individual results are not equivalent to those of the participants in the control group).

We performed the most analysis at the level of primary health care unit and compared intervened vs control groups since the available data did not allow for identifying each of the participating GPs, so not allowing to distinguish in the intervention units, which GPs were compliant with the intervention (so the GPs that actually used the DBCI ePrimaPrescribe Platform complying with the intervention), from those that, although initially agreeing to participate, finally did not use the platform.

As our inclusion criteria were very broad - including all BZD prescriptions - we have included an undetermined percentage of patients that might suffer from severe mental health disorders and to whom discontinuation of BZD might be unappropriated.

Regarding clinical diagnosis outcomes, we recognize that our data might be an inexact approach, since most prescriptions are not associated with a diagnosis, and because even when this association was found, it did not mean that symptoms or disorders were identified at the moment of prescription. Despite this limitation, we considered it relevant to report the analysis of the change in clinical diagnosis, since it might indicate significant secondary effects coming from the intervention implementation.

Conclusions

The trial failed to demonstrate the effectiveness of our intervention implementation in BZD or antidepressant prescription trend and diagnosis coding. However, our study gives relevant intel regarding compliance with interventions aiming to change prescription behaviour in primary health care settings. Also, and in a broader sense, we consider that our results should encourage a profound reflection on the management of common mental disorders in primary health care settings.

Since the beginning of the study implementation (May 2017), the COVID-19 pandemic has forced doctors (including GPs) into the digital era, bringing on a rapid and massive uptake in the utilisation of digital tools to allow the maintenance of clinical care. Thus, we consider that the replication of our mode of delivery, if carried out now, would probably have better acceptability, practicability, and effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ricardo Vicente e Cátia Pinto, from SPSM services for facilitating access to data extraction; all primary health care unit coordinators in Alentejo central region for facilitating the study implementation, and to all GP who openly charred their perspectives and willingly participated in the study.

Authors contributions

TAR, HS and MX conceived and designed the study; TR and SA calculated the sample size and performed the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript, refined the study protocol and approval of the final manuscript.

Ethical approval

This trial was approved by the Ethics Commission for Health of the Regional Administration of Health for Alentejo Region (Portugal) (02/2016(CES)), and the Nova Medical School, Nova University Lisbon, Portugal Ethics Commission (47/2016/CEFCM). The results of this study were disseminated via peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations.