Introduction

At the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations agency, many heads of states and governments unequivocally stated that these are unprecedented times, marked by the emergence and spread of a novel coronavirus, first detected in Wuhan province in China in late 2019. Among the prominent religious leaders who added their voices was the Dalai Lama who advised that “this pandemic serves as a warning that only by working together with a coordinated global responsibility can we meet the challenges we face now”,1 a call echoed by Pope Francis. There was no doubt that these were times without parallel; indeed, the need for a coordinated global response became even more evident as scientists endeavoured to develop vaccines within an extremely short time. Understandably, each country reacted to COVID-19 based on its own specific circumstances, underpinned by unique cultural, historical, geographical, political, economic and strategic interests. The world’s richer nations and governments rushed to procure millions of doses - enough to vaccinate their citizens five times over - while the populations in the majority of the poor countries remained unvaccinated in the face of more infections variants such as the Omicron.

Given that individual countries were issuing their own responses to the spread of the coronavirus, on 7 April 2020, the Council of Europe released guidelines on “Respecting Democracy, Rule of Law and Human Rights in the Framework of the COVID-19 Sanitary Crisis. A Toolkit for Member States”. In these guidelines, the Council of Europe recognizes:

that governments are facing formidable challenges in seeking to protect their populations from the threat of COVID-19. It is also understood that the regular functioning of society cannot be maintained, particularly in the light of the main protective measure required to combat the virus, namely confinement. It is moreover accepted that the measures undertaken will inevitably encroach on rights and freedoms which are an integral and necessary part of a democratic society governed by the rule of law. The major social, political, and legal challenge facing our member states will be their ability to respond to this crisis effectively, whilst ensuring that the measures they take do not undermine our genuine long-term interest in safeguarding Europe’s founding values of democracy, rule of law and human rights. It is precisely here that the Council of Europe must carry out its core mandate by providing, through its statutory organs and all its competent bodies and mechanisms, the forum for collectively ensuring that these measures remain proportional to the threat posed by the spread of the virus and be limited in time. The virus is destroying many lives and much else of what is very dear to us. We should not let it destroy our core values and free societies. (Council of Europe, 2020: 2)

The Council further clarified that it was left to each member state, “with its responsibility for ‘the life of [its] nation’, to determine whether life is threatened by a ‘public emergency’ and, if so, how far it is necessary to go in attempting to overcome the emergency” (European Court of Human Rights apud Council of Europe, 2020: 2). It is against this backdrop that that this paper examines Sweden’s controversial approach to the coronavirus. Sweden, with a population of 10 million, took a different path when compared to most other counties (Rambaree and Nässén, 2020), and ultimately became one of the top 20 in the world with the highest number of coronavirus-related deaths per capita. The Swedish national approach departed from the strategies of Denmark, Norway, and Finland, which introduced stringent measures (Petridou, 2020), including the closing of borders, even though these countries are historically proximate and culturally similar. In this paper I argue that Sweden’s approach to the COVID-19 crisis was largely informed by a poised national self-image and a general sense of propriety of behaviour and trust in the Swedish society. Following this line of argument, I endeavour to illustrate how the notions of “individual responsibility” and “mutual trust” between the government (and various agencies) and the citizenry predicated on the poised national self-image and a traditional sense of propriety of behaviour, are deployed to control the spread of the virus.

1. Methodological Considerations and Data

For our purpose, critical discourse analysis (CDA) provides useful tools for the analysis of two categories of the “texts”: (a) the national strategy for handling COVID-19 as presented in speeches and documents by the Minister for Health and Social Affairs, the government chief epidemiologist and the Director General of the Public Health Authority (PHA) and (b) the visual guidelines and recommendations posted in different public places. The analysis relies largely on the work of van Dijk (1993, 1998), and Fairclough (1989, 1995, 2001). Commenting on the use of CDA, van Dijk suggests that it is possible to “go beyond the immediate, serious or pressing issues of the day” (1993: 253). In this case, the pressing issue is the spread of coronavirus; therefore, the analysis can go beyond the immediate impact and look behind the policies upon which the approach or the national strategy is based. From Fairclough’s perspective, “Discourses include representations of how things are and have been, as well as imaginaries - representations of how things might or could or should be” (2001: 4). This perspective is helpful in the analysis of how the key elements of the Swedish poised national self-image are imagined and articulated in the choice of the words used to communicate the guidelines and recommendations directed to the public with a view to limiting the spread of the virus.

In his reading of Fairclough’s CDA, Janks (1997: 329) outlines the three-dimensional model thus:

1. The object of analysis (including verbal, visual or verbal and visual texts);

2. The processes by means of which the object is produced and received (writing/speaking/designing and reading/listening/viewing) by human subjects;

3. The socio-historical conditions which govern these processes.

According to Fairclough each of these dimensions requires a different kind of analysis:

1. Text analysis (description),

2. Processing analysis (interpretation),

3. Social analysis (explanation).

I use this model to aid the analysis of the texts and the specific language chosen by the Swedish agencies to advise the public to keep social distance and adhere to the regulations put in place during the pandemic.

The study is qualitative in design, drawing from a range of interactive approaches and methods, within an ethnographic framework. The data on which the paper is based were gathered through listening to the presentations of the national strategy for handling the pandemic, which were made by the leadership of the Public Health Agency (Folkhälsomyndigheten), a scrutiny of the debates in the print media, and the recommendations and guidelines posted by relevant agencies and affixed in public spaces such as parks, supermarkets, restaurants, and means of public transport. Additional data were gathered through interviews and observations made by this author in different places across Sweden. Through interviews, it was possible to gather data on the public perceptions of the national strategy. Through observation in selected sites, it was possible to see how the public reacted to such divisive issues as the use of masks and keeping social distance.

1.1. The Extent of Data Analysed

The research was carried out in two large cities, one middle sized town and a suburb, respectively, Stockholm and Uppsala, Tierp, and Västerås. Sixteen individual interviews and three mixed focus group discussions were conducted with a wide range of people (men, women, youth), and twenty visits to selected pubs and coffee houses were conducted by this author to gain insights into how the guidelines were followed while such public facilities were kept open during the pandemic. During the visits to pubs and coffee houses, to listen and observe, useful data were gathered from members of the public engaged in these informal discussions, arguing back and forth about the national strategy and other pertinent issues, for instance, whether vaccination should be mandatory. This method proved particularly useful for collecting data based on views and opinions as people debated the national strategy, and at the same time, questioned each other’s understanding of how to deal with the threat of the pandemic. Twenty-six texts (recommendations and guidelines) posted on buses, trains, via roadside signboards, and in public parks were identified for analysis. Also, data were gathered through observing how members of the public reacted to the guidelines posted in shopping malls and supermarkets. The terms “guidelines” and “recommendations” are used together or interchangeably throughout this paper. However, in the case where an individual is expected to decide to stay home if one is sick, I interpret this to be a guideline on how one should act in the given circumstance.

2. The Swedish National “General Strategy” for Controlling the Spread of Coronavirus

It is this paper’s contention that the Swedish national self-image contributed to shaping the country’s response to the threat posed by the coronavirus. In what Habel (2012: 100) describes as Swedish exceptionalism, the society visualizes itself as distinguished “by virtue of its welfare politics, and its democratic, egalitarian principles”. For decades, Sweden has imagined itself as the champion of the “Nordic model” embodied in a comprehensive welfare system. The point being made here is that while most of the world was under lockdown during the pandemic in 2020, Sweden, inspired by its self-image and a deep sense of propriety of behaviour, took a different path. Sweden chose not to implement a “forced mass lockdown” to keep the economy open. Compared to her Nordic neighbours, on 27 July 2020, the coronavirus death toll was as follows: Sweden - 5700, Denmark - 613, Finland - 329 and Norway - 255. Similarly, the cumulative numbers of coronavirus infection cases in the Nordic countries showed the following trend: Sweden - 79395, Denmark - 13547, Norway - 9117, Finland - 7398, Iceland - 1854, Faroe Islands - 214 and Greenland - 13.2 Evidently, Sweden’s upward trend of COVID-19-related deaths continued, and ultimately the country attained the highest death rate in the region, with 19,325 recorded cases by August 2022.3

In her speech at the WHO briefing on 23 April 2020, Lena Hallengren, Sweden’s Minister for Health and Social Affairs, was quoted as saying that:

We are very practical and open to implementing any measures that we think would be effective. But to understand our approach, it helps to be aware of some fundamental characteristics of Swedish society […]. There is a tradition of mutual trust between public authorities and citizens. People trust and follow the recommendations of the authorities to a large extent.4

Similar sentiments were echoed by some individuals interviewed by this author,5 who stated unequivocally that “a forced lockdown is antithetical to Swedish ethos”,6 regardless of fact that Sweden, with a population of 10 million, had the highest corona death toll per capita. From a critical discourse perspective, the public discourse on forced lockdown was premised on a perception of Swedish ethos. Unsurprisingly, Sweden was lambasted by international print and digital media, with blazing headlines on the government’s peculiar approach to the coronavirus. It was also shunned by neighbours Denmark, Finland and Norway who maintained travel restrictions on Sweden even when they eased them for other countries. In June 2020, The Guardian carried a debate article highlighting the issues arising from the Swedish controversial approach to COVID-19:

The result is a highly cloistered discourse in which a few dozen Swedish media pundits determine what is and isn’t deemed permissible debate: and the idea that Sweden had got it completely wrong on coronavirus was considered anathema. Quickly, the weight of opinion - through analysis in opinion pages, and broadcast and social media - laid emphasis on the view that Sweden was doing the right thing by refusing to engage in a mass lockdown or deploy a test, trace and isolate model. Despite this being totally out of line with the rest of the world.7

It is not possible to say to what extent the Swedish national self-image has been marred internationally by this decision to go against the grain; however, widespread sharp criticism persisted as the coronavirus continued to claim lives. In response to the criticism, the Minister for Health and Social Affairs once again invoked the view of Swedish exceptionalism: “We do what we think is best based on the development of the pandemic in Sweden, and our national circumstances”.8 It is not clear what the minister meant by “national circumstances”, but with the hindsight afforded by the excerpt cited below, perhaps it was a reference to the notions of ethos, tradition, and devolution of powers to different expert agencies, including the PHA.

In early June 2020 Johan Carlson, the Director General of the PHA at the time, presented the public with a detailed explanation of how the agency was handling the coronavirus. He also communicated the nation’s general strategy to control the spread of the disease in the country. Rather painstakingly, Carlson emphasised the importance of international collaboration as well as the government’s reliance on the advice of the expert agencies, based on science, to make decisions on how to control the spread of the virus. Below is an excerpt from the presentation:

Our response is also developed in collaboration with regional, national, and international partners because Sweden is a very devolved country, the local authorities, the regions have the overall responsibility for communicable disease prevention and control, so we need to have a close collaboration with them. And also we have had in Sweden a consensus to avoid a lockdown, penalties, etc., based on our tradition. Some features of the pandemic response could be called “generic” - track, trace, protection, and measures to control transmissions, estimate and model the spread, etc., done in all countries. But how these measures are being implemented is highly context-specific, depending on a number of factors in a country, such as the general health of the population, resources, health care system, political system, etc. […]. The Swedish system is very devolved we need to base everything on the local authorities. The general strategy is a strategy of shared responsibility, based on advice from expert agencies. It is also aiming at minimizing the spread as much as possible without a total lockdown […]. It is based on social distancing and hygiene routines […]. It is also meant to be very flexible. We like to adjust the measures depending on the situation. We also like […] to avoid over-responding, making the situation worse when it comes to other health threats […] we would like to have a sustained response that could last for a long time because we know this is not the end of it, it is rather the start of combating this pandemic.9

In the previous excerpt, the Director General of the Public Health Agency describes the structures in Sweden and highlights the merits of being a very decentralised country for the purpose of controlling the spread of the virus. Thus, he relied on the prevailing public understanding of the underlying social and political structures to explain why it would be considered vital to reach a consensus based on tradition when considering the question of whether or not to implement a lockdown. Implicit in his explanation was the conviction that the decision not to impose a lockdown would be (as expected) in line with Swedish values and norms. Admittedly, in the explanation proffered, science is subjugated to the value of tradition, and having thus underscored Sweden’s exceptionalism, the internationally accepted measures being implemented in other countries were dismissed as generic.

Furthermore, since the aim is to explain why lockdown is unnecessary (or inappropriate), the general strategy should be very flexible, it must reflect the traditional notion of doing things in moderation (including response to COVID-19), in other words, being calm the Swedish way (lugn) to avoid over-responding, in other words, implying over-reacting. Besides discrediting the measures implemented in many other countries, and extolling Sweden’s apparently reckless approach to coronavirus, Johan Carlson in the previous excerpt emphasizes the importance of responding to COVID-19 based on an interpretation of Swedish tradition. Admittedly, Carlson subscribes to the idea that adherence to tradition is important for creating a consensus against a lockdown. One can conclude that appealing to the notion of consensus-building, which relies heavily on the individual conviction against a lockdown, is given more weight than the prevailing evidence showing that lockdown could effectively reduce the spread of the pandemic.

3. Managing COVID-19 through Mutual Trust

To avoid an enforced lockdown, the Swedish government presented a range of different measures, both voluntary and legally binding, to limit the spread of COVID-19, as Lena Hallengren put it. In the following excerpt, Hallengren further explains the government’s decision not to implement confinement measures:

Our generous welfare systems make it easy for people to stay at home when sick. However, we have carried out some additional changes to strengthen the incentives for people to stay at home, away from work when they show even the slightest symptoms. Employees and self-employed people will get paid sick leave from day one, and we have waived the need for a doctor’s certificate […] we aim for strategies that last over time and have public trust. Sweden’s efforts consist of a combination of legislative action, strong recommendations and guidelines, awareness raising and voluntary measures. Measures need to last over time and be acceptable to the public […]. So far, it has not been necessary to implement a total lockdown of the whole of Swedish society or implement confinement measures. Our assessment at this point is that people mostly follow recommendations issued by the Government and the responsible authorities. This makes us convinced that strong legal measures are not the only way of achieving behavioural change.10

By associating the people’s willingness or choice to stay at home when sick with the generous welfare system, the Minister diminished the significance of one of the fundamental guidelines of COVID protection, affording it to individuals, namely, to stay home to control the virus, to save lives and protect the health system from being overwhelmed if many people got severely ill at the same time. Clearly, Hallengren underscored individual responsibility - allowing individuals to decide if or when to stay home - to the detriment of the collective effort to prevent the spread of the virus. People were also advised to stay home if they were sick and then two days more after they got well, regardless of what infections they had. After all, the government has played its part by giving incentives allowing people to make individual decisions. Thus, the people relied on the government to provide solutions to problems, and the government relied on the people to exercise their sovereignty and a sense of individuality in a responsible manner. There is no doubt that this emphasis, which bolstered the individual sense of sovereignty, failed to consider the potential benefits of a collective approach in the face of a global pandemic. The advice from the PHA “to stay home rather than going out with a facemask” (Pashakhanlou, 2021: 513) was contrary to the WHO guidelines.

Besides the emphasis on the individual responsibility to curb the spread of the virus, the Minister explained the government position that enforced legal measures were not the only way to achieve public compliance (behaviour change). Here, convinced that forced lockdown could not induce the necessary behaviour change in compliance with the recommendations, the Minister focused on reciprocal trust - government trust in the people and the people’s trust in the government approach to COVID-19. Similarly, in one of his regular briefings in March 2020, Anders Tegnell, the chief government epidemiologist, emphasised the role of individual responsibility in curbing the spread of the virus thus: “Our public health system works very much on the basis that the individual takes a lot of responsibility. […] That is how our legal system is build up not to transmit any kind of disease to anybody else”.11 Regarding the general approach to the pandemic, he reiterated that “We always said we want to get the spread down as much as possible; that has been our goal to use any kind of method that we deem relevant and not too damaging to public health. That is not unethical or an unreasonable way to think about things”.12

In this statement, Tegnell, too, evokes elements of the underlying Swedish ethos, namely, being reasonable and not over-reacting. Thus, the public would understand the government’s preference for advice and recommendations as emanating from the principles founded on a society in which the law guarantees freedom of movement and where coercion or enforced compliance to public policy would be frowned upon. An analysis of the recommendations and guidelines to the public further reveals the extent to which the government relied on one’s individual responsibility to prevent the spread of the virus; that is, the individual was left to interpret the guidance given the public. Below are some of the guidelines and recommendations disseminated to the public.

4. Textual Analysis of the Guidelines and Recommendations from the Public Health Authority

The guidelines and recommendations which follow13 illustrate the emphasis on the individual rather than a collective approach in the COVID-19 strategy. The individual approach is stressed by Stefan Löfven, Sweden’s Prime Minister in his speech in March 2020, where he sees the solution as

the individual and the willingness of the individual to follow the recommendations made by the government and the responsible agency: “The only way we can cope with this is that we approach this crisis as a society where everyone assumes responsibility, for his- or herself, for one another and for our country”. (Sjölander-Lindqvist et al., 2020: 19)

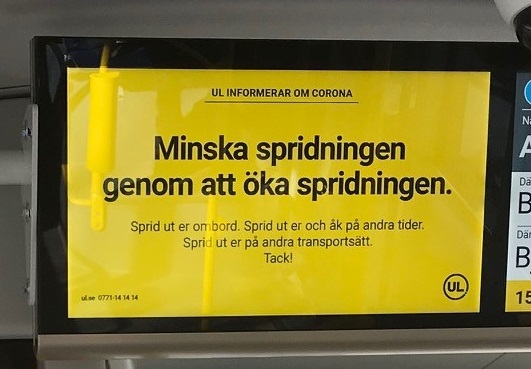

The guidelines in Image 1 were meant for individuals to follow as they went about their business in different places.

Image 1 “Decrease the Spread by Increasing the Spread”. Translation of the small print: “Spread yourselves out on the bus. Spread yourselves out and travel at different times. Spread yourselves out in other means of transport. Thanks!”. Source: Photograph taken by the author in an Uppsala city bus.

The recommendation presented in bold print can be directly translated as “Decrease the spread by increasing the spread”. Visually the text in bold print is situated at the centre of a yellow background, and these visual properties of bold black large print on the yellow background enhances the importance of the message therein. Yellow colour is often used for traffic and road signs, therefore, one can suggest that it is being used as background of the image on the bus for its visual properties. Also, the choice of the background colour for the image could have been based on the fact that people are cognitively familiar with yellow warning signs. Perhaps, from this perspective we can assume that the image was intended to attract attention as a warning to the passengers in the bus. In the small print, the message is explained thus: “Spread yourselves out on the bus. Spread yourselves out and travel at different times. Spread yourselves out in other means of transport. Thanks!”. However, the message of the guideline - meant to serve as an explanatory note to the text in bold print - fails to clearly and directly communicate that the passengers in the bus should keep some distance from each other. The words used in Swedish do not expressly inform them of the importance of social distance in public transport as a way to curb the spread of the coronavirus. At most, it is confusing, indirect, and even misleading. Furthermore, it is difficult for passengers sitting in the bus to read the small print to see the explanation of the message in the large print. Therefore, it would be natural to conclude that the passengers were left to work out the meaning of the bold print without the benefit of the explanatory note. Moreover, given how it uses a play on words, it is potentially more challenging to translate and interpret the message in any of Sweden’s minority languages (Arabic, Somali, Amarinya, etc.) in which crucial public health information is regularly disseminated for the benefit of ethnic minorities living in the country. Following Janks’ Critical Discourse Analysis (1997), I reflect on how the passengers in the bus relate to these guidelines and as they endeavour to translate and understand the content of the text on the yellow background.

The guidelines in Images 2-6 illustrate the different messages contained in the guidelines and recommendations given to the public by the health authorities.

Image 2 “Take Care of Each Other. Keep Distance” Source: Photograph taken by the author by the roadside, Uppsala.

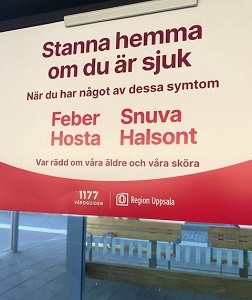

Image 3 “Stay Home If You Are Sick”. Translation of the small print: “When you have any of these symptoms: fever, runny nose, cough, sore throat, take care of our elderly and our vulnerable”. Source: Photograph taken by the author at a bus stop, Uppsala.

Image 4 “Think about the Distance. Do [Your] Shopping with Consideration”. Source: Photograph taken by the author in a supermarket, Uppsala.

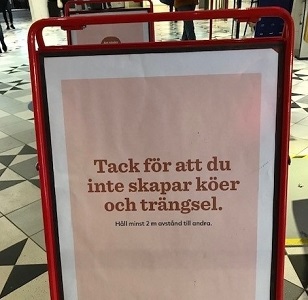

Image 5 “Thank You for Not Creating Queues and Congestion”. Translation of the small print: “Keep at least 2 meters distance from others”. Source: Photograph taken by the author at a bus stop, Uppsala.

Image 6 “Thanks for Keeping Your Distance”. Source: Photograph taken by the author in a shopping mall, Uppsala.

These guidelines communicate different messages. One would think that visually, they are presented in different colours and varying font sizes, for visibility and emphasis. However, following Janks (1997: 335), I have identified certain features of the texts for analysis:

the use of ambiguous phrases;

the tone of the message - given as courteous advice, not instructions;

the information not focusing on COVID-19.

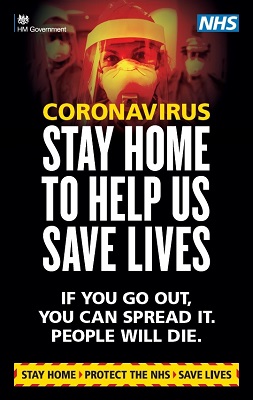

Evidently, unlike the clear, simple, and precise guidelines given to the public in the United Kingdom (UK), presented on Images 7 and 8: “stay home. protect the nhs. save lives”,14 in Sweden citizens were expected to rely on their own knowledge and experience, along with cultural conventions and social practices to interpret the different recommendations and guidelines and decide what action to take - whether to stay home. Unlike the Swedish variety of guidelines with different messages, the message in UK guidelines remained constantly and essentially the same: stay home. protect the nhs. save lives. Even when this guideline was presented with additional texts, the aim was to make clear to the public what would happen if they did not follow the guidelines. The main message remained essentially the same, clearly recognizable by the public across the country.

Image 7 An example of a UK Guideline. Source: UK Department of Health Care guidelines to the public. Available at https://www.campaignlive.co.uk/article/nhs-introduces-vivid-imagery-front-line-crisis-latest-ad/1679298 (last accessed on 17.07.2022).

Image 8 Another example of a UK Guideline. Source: UK Government Department of Health and Social Care. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-tv-advert-urges-public-to-stay-at-home-to-protect-the-nhs-and-save-lives (last accessed on 17.07.2022).

Discourse “is the way people interpret the information that comes from a wide range of sources” (Jabar et al., 2017: 357). Relying on this perspective, I argue that the words in the Swedish guidelines and recommendations to the public to control the spread of the virus were soft, framed in familiar local idiom and imbued with a deep sense of local sensibilities and common sense. The government and relevant agencies relied on the public’s interpretation of the intended implicit meaning of the guidelines, based on the underlying cultural understanding that Swedes do not like to be given instructions on how to act. Unlike the ambiguous Swedish recommendations illustrated before, the guidelines provided to the public by the British Government, following the advice of scientific experts, are straightforward and concise, hence unlikely to be subject to variations stemming from individual interpretation and depending on a variety of factors, including the choice and tone of the message.

The previous guidelines are couched in polite language; people are not ordered, they are courteously advised to be considerate or to keep distance. More importantly, the choice of language is in line with the underlying ethos, namely, being lugn (calm, quiet, dispassionate), as previously mentioned, in word and action. It is also clear to the reader that the primary message, as seen in the Images 1 to 6, is confusing and not easily understood. It literally says in bold letters “Decrease the spread by increasing the spread”. Arguably, it is not a straightforward message that is intended to instantly and plainly communicate the importance of observing social distance on board a public transport bus because of the pandemic. On one occasion, a passenger on the bus myself, I had to look at it several times to understand the dual meaning of “spread”. Similarly, another opaque message reads simply, “take care of each other”, while the recommendation posted in a supermarket vaguely advises people to “think about the distance” and “do [their] shopping with consideration”. These two messages are not overtly specific to the COVID-19 situation; they could well have been disseminated in any situation.

Leaning on Fairclough’s (1989, 1995) well known dimensions of CDA, Janks (1997: 329) makes a useful suggestion that it is possible “to focus on the signifiers that make up the text, the specific linguistic selections, their juxtapositioning, their sequencing, their lay out and so on”. This perspective is helpful for understanding how the words used in the prior messages are organized and sequenced to evoke one’s individual sense of responsibility to do what is expected of them by the authorities in a “mutual trust relationship”. Certainly, this approach puts the duty of preventing the spread of the virus squarely on the individual. The question is: could these messages - “texts”, to use Fairclough’s terminology - have been presented in a different way with the same impact in the same context of trust and sensibility?

Relying on the mutual trust between the government and the citizenry, the nation’s schools, restaurants, and cafés remained open because Sweden is a very open society, as Carlson, the Director of the PHA, stated. The extent to which trust and individual responsibility are intertwined in Sweden is reflected in the fact that citizens do not need a doctor’s certificate to confirm that they stayed home because they were sick. It seems that it is crucial to maintain such overriding trust from the public because it is widely believed that people will do the right thing; they will follow the advice given and act accordingly, without enforcement of compliance, as some people said when asked during the interviews for this paper, if they were satisfied with the government’s COVID-19 strategy.15

The Swedish guidelines and recommendations are different in important ways and they communicate different messages. Relying on Fairclaugh’s dimension of discourse and discourse analysis, Janks (1997: 333) suggests that: “The different discourses available for readers to draw on provide different conditions for the reception” and interpretation of the text in “different contexts”. Helpful to our analysis of the texts above is Janks’ observation that “reference to the context of production and reception” (ibidem) is important for the interpretation of the text as it is relevant for the way the public might interpret the texts under scrutiny here. In Sweden, it is assumed that most people would find the guidelines acceptable and therefore follow them as expected. However, the guidelines were framed in such a way that they are left open to individual experience, with each person free to deconstruct and interpret the messages they conveyed.

5. COVID-19 Impact on People with Migrant Background

There is no doubt that the pandemic affected the population unequally. Johan Carlson, the Director General of the PHA, reiterated that “The pandemic has affected the population very unequally. It is not only that people of lower socio-economic status have been infected more […], mainly due to over-crowding, not being able to understand, if you are of a foreign origin, for example, all the advice”.16 Furthermore, he notes that

it is also that the response as such has unequal consequences and effect. For example, if you work in the service sector, if you are a bus driver, if you work in a shop […] in a restaurant […], you need to go, you need to be out and be more at risk of contracting the disease. You cannot avoid public transport.17

What he did not include were other groups at risk, such as the elderly living in care homes who were the most vulnerable to coronavirus infection.

In the early days when the coronavirus began to spread, leading politicians warned that there was a high risk of infection in areas with large immigrant groups. Soon, the Järva area in Stockholm hit the headlines after it was broadcast on the Swedish TV that the majority of those who died of the coronavirus were Swedish Somalis. This was followed by news about the spread of the disease in two other areas - Rinkeby-Kista and Spånga-Tensta where the residents are predominantly of migrant background. This biased reporting caused further alienation of these groups, who were accused of spreading the virus. Running contrary to the popular image in which Sweden displays an egalitarian society, the communities in these areas are socially and economically vulnerable low-resource groups, living in segregated areas with inadequate housing and experiencing segregation in schools. Given these circumstances, they were severely affected by the coronavirus crisis; however, Johan Carlson attributed the high rates of infection among these communities to what he considered to be their inability to comprehend the advice disseminated to the public by the agency. This line of argument was premised on the assumption that the people with an immigrant background are less likely to comprehend the advice which is communicated in Swedish. However, several people who participated in this study, dismissed the argument as motivated by racist bias against sections of the population with an immigrant background.

To control the spread, the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (Myndigheten för samhällsskydd och beredskap - MSB) was tasked by the government to look into how information could be effectively disseminated to all the groups to be able to protect themselves from the virus. SB acknowledged that challenges arise in a society with many groups, but nevertheless attention was directed towards different (foreign) backgrounds and language skills. The Agency said that in the prevailing circumstances, they were not in a position to reach these groups. Responding to this, members of the groups from migrant backgrounds who felt more vulnerable in these extraordinary circumstances pointed out that “it is not just about handing out information sheets. It’s about saving lives”.18 In these words, they aptly summed up what needed to be done at the height of the pandemic.

The Director General of MSB, Dan Eliasson, also attributed the impact of COVID-19 on the people of foreign background who, it is assumed, are not able to understand all the evidence and the guidelines being provided. Yet, as the previous examples show, the guidelines were ambiguous, for instance, when compared to the clear and precise UK example also cited. Generally, racism is an uncomfortable topic for many Swedes, and here we are informed by van Dijk (1993: 262) who points out that “intentionality is irrelevant in establishing whether discourse or other acts may be interpreted as being racist”. Inequality and racial discrimination in Sweden are a reality that those known as “people with foreign background” must endure. Admittedly, structural racism is the opaque side of what is being referred to here as Sweden’s poised national self-image. It seems that while the government trusted individuals to understand the advice and recommendation to curb the spread of the virus, the same level of trust was not extended to the sections of the population identified as people of foreign background. Evidently, the leadership of the relevant agencies did not take into consideration the importance of culturally sensitive methods of disseminating crucial information; for instance, in some communities in segregated predominantly minority areas in large cities, the source of information must be known, trustworthy and appropriate to the community and individual sensibilities. In this way, the communities and individuals are more likely to abide by the public health advice and recommendations disseminated via known and trusted sources such as local community and religious leaders.

6. Dwindling Trust in the Government’s Handling of the Pandemic

In the early months of the pandemic, the level of the public trust in the way the government was handling COVID-19 was sustained as some put it - “We in Sweden trust the authorities and if they say ‘please stay at home, and work from home’, we do that. So, they did not have to say ‘you have to go on lockdown’”.19 However, despite the declining numbers by June 2020, some discontent with the way the government was handling the spread of coronavirus was being expressed. The Prime Minister appointed a Commission to investigate the country’s response to COVID-19 after a growing debate on the death rates in elderly care homes. In August 2020, the PHA, despite its controversial approach, reported a sharp drop in fatalities with daily admissions to ICU down to a single digit.

Increasing infection rates and fatalities triggered a mixed reaction, with public opinion pointing a finger at the government’s handling of the pandemic. On the one hand, those who felt that the regulations should not be enforced at the expense of individual liberties said they were satisfied (a Swedish expression of approval) to have more freedom than the rest of the world during the pandemic. On the other hand, trust in the government strategy was waning, however slightly, as some people felt that the Swedish approach was coming under pressure. Some of those who were interviewed by the media in the streets of Stockholm said that “The natural thing would be to shut things down a bit… I do not understand why we are not being a bit more careful. I don’t understand. Sweden has one of the highest death tolls in Europe in relation to its population”.20 Those who expressed dissent were critical of what they saw as a system where the expertise of the PHA led by advising the government, rather than government being able to lead by using the scientific expertise. It is worth noting here that “the ability to work effectively across sectors to minimise the spread of COVID-19” could have “been further hampered by a decentralised and fragmented system of health and social services, including the care of older people” (Claeson and Hanson, 2021: 260).

As the debate raged on, there were concerns about how the strategy, which had come under heavy criticism from other European countries, particularly neighbouring countries that closed the borders, would affect Sweden’s global image. Admittedly, although Sweden’s relationship with her Nordic neighbours is important, it was tested by the pandemic.

In November 2020, however, the surge in hospitalization cases, fatalities and the rate of infection to a thousand a day prompted the government, which had hitherto avoided imposing an enforced COVID lockdown, to call for stricter measures. Compared to its neighbours - Norway and Denmark which are also “trust-based” societies - Sweden had 633 deaths per one million, while Denmark had 136 deaths per one million, and Norway had 233. A ban on gatherings of more than eight people, attending entertainment performances or demonstrations and keeping pubs open after 10 p.m. was introduced. The government assumed a tougher stance after facing mounting criticism for failing to enforce a lockdown unlike other countries in the Nordic region and Europe in general, and despite high death rates per capita.21 At a news conference on November 3rd, the Prime Minister was quoted as saying: “We are going in the wrong direction […] The situation is very serious… Every citizen needs to take responsibility. We know how dangerous this is” (apudHabib, 2020). He was urging the people to take responsibility to control the spread of the virus. However, by late December 2020, COVID-19-related deaths in Sweden were “4·5 to ten times higher than its neighbours” (Claeson and Hanson, 2021: 259). This was not surprising, considering that the so-called stricter measures were not mandatory. The government continued to rely on people to voluntarily follow the guidelines and prevent the spread of the virus.

It was widely believed that

From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Public Health Agency […] embarked on a de-facto herd immunity approach, allowing community transmission to occur relatively unchecked. No mandatory measures were taken to limit crowds on public transport, in shopping malls, or in other crowded places, while recommending a limit of 50 people for gatherings. (ibidem: 259-260)

Yet the 50 people limit rule did not include schools, public places such as libraries, shopping malls and a host of other spaces and events. This lack of a uniform approach not only failed to encourage public adherence to voluntary careful and vigilant behaviour, but its inherent ambiguity also created confusion and bewilderment in times of uncertainty, as many people felt the need to choose the right thing to do, while others felt and acted differently. Deciding the number of people that should be allowed into a shop at a time was a clear example of how interpretations of the stricter regulations would vary amongst the public. I observed that people were nearly always confused when they were asked to leave the shop if that specific shopkeeper had decided that there were too many people inside at the same time to be able to respect the necessary social distance. Several shops and business owners in Uppsala introduced a shopping basket system to count the number of customers allowed into their establishment at any given time. The shopping baskets, 10 or 20 depending on the size of the shop, were placed at the entrance, and each customer was required to take one basket into the shop. This meant, therefore, that if the shop had reached capacity and no baskets were available, the customer would have to wait for a free basket to enter. However, this rule was also confusing and even difficult to enforce efficiently; for example, on three occasions, I observed in different shops that some customers declined to follow this rule, citing their freedom of choice, insisting that they could not be forced to take a basket if they did not wish to do so.

7. Discussion: Emphasis on Individual over Collective Responsibility in the Face of a Global Health Emergency

A close analysis of the data reveals that the messages and guidelines given to the public by the PHA were often framed in imprecise language to avoid giving direct orders to the public. Evidently, the PHA emphasised the primary role of the individual over collective responsibility in the face of a global health emergency. In the spirit of the Swedish ethos and tradition, giving direct orders to the public is frowned upon and not appreciated as a way of dealing with times of crisis. Hence the measures and guidelines were cloaked as advice using considerate manners and language. When direct instructions were given, people were told “Work from home if you can”, “If you are coughing or have a cold, stay home” and “Travel if you must”. These were personal guidelines that placed the responsibility squarely on the individual. They did not spell out the inherent danger if people mixed or met up with others. Thus, the sense of emergency and threat from the virus were played down, wittingly or unwittingly, by the choice of the language used - both the words and the mood of the messages which were purposely friendly and soft. At the same time, the emphasis on the individual responsibility over the collective efforts to control the spread of COVID-19 ignored the fact that the pandemic was a global public health crisis. Relying on the data generated during the visits to the shops, I argue that the inherently conflicting guidelines (friendly advice, voluntary nature, and at the same time legally binding) created confusion amongst the public. No wonder, as some studies have shown (Sjölander-Lindquist et al., 2020), not everyone adhered to the guidelines. At most, two thirds of the people may have followed the guidelines but with coffee houses and bars open even for regulated times, people might not have been aware that they had COVID-19 until symptoms began to appear. They would go out anyway.

In the absence of strict measures to control the spread of the virus, some people felt that they were not safe, even if they took personal responsibility to follow the guidelines. Also, some individuals seemed not to take the guidelines seriously, and this made others uncomfortable. For instance, while some felt that wearing a mask in public was necessary, others felt that they should be left to exercise their right to freedom of choice; therefore, they could not be forced to follow the guidelines. Those who complained about the confusion arising from the competing demands of individual freedom of choice on the one hand, and the responsibility to prevent the spread of COVID-19 by following the guidelines on the other, blamed the government for the high death rates in elder care homes. Eventually a feeling of being let down took hold, while others felt that the government did the right thing by avoiding an enforced lockdown. In the defence of the national COVID-19 strategy, the government argued that they did what was appropriate for Sweden. Ultimately, the emphasis on individual responsibility did not give room to mobilize a collective effort in the face of a global pandemic.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have endeavoured to examine Sweden’s national strategy for curbing the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic through an analysis of Swedish society’s notion of self-understanding, one predicated on individual action, the trust citizens place in their government, and how the government, in turn, trusts its citizens’ sense of responsibility. This two-way trust was based on the underlying notions of propriety of behaviour, summed up as the Swedish ethos and the country’s tradition.

The virtue of being calm when you address a situation, even a challenging one, is a core Swedish value, and its manifestation cannot be overstated in relation to the national strategy to control the spread of the coronavirus. Chief government epidemiologist Tegnell was responsible for regular media briefings during the COVID-19 crisis and soon he became the face of the government’s strategy. He received love and hate in equal measure - vitriol from harsh critics who accused him of sacrificing people at the altar of national pride along with widespread praise from his admirers, with a few people going so far as to have a tattoo of his face. In the local media, he was described by the Swedish epidemiologist and science writer Emma Frans thus: “He’s a low-key person. I think people see him as a strong leader but not a very loud person, careful in what he’s saying. I think that’s very comforting for many”.22 She further suggested that many national and international media outlets had been “searching for conflict” within the scientific community, whereas she believed there was a consensus that Tegnell’s approach was “quite positive”, or at least “not worse than other strategies”.23 This is an opinion to which many people in Sweden would subscribe because, given how being quiet is valued, and not speaking in a loud voice is cherished in the Swedish tradition. It seems that to many, his demeanour was more important than the veracity of the information he presented to the public.

When asked about the aims of the Swedish strategy, Tegnell said: “Finally, we are where we hoped [to be] much earlier on. We can see the trend we had hoped for”.24 When pressed further, asked about whether herd immunity was the goal, his response was that “it wasn’t the point of the Swedish strategy, but something that you thought would be an outcome.” The issue of whether or not achieving herd immunity was the aim is core to the public discourse - the success or failure of the Swedish approach. This statement, therefore, is subject to interpretation, and relying on Fairclough’s CDA three-dimensional approach, it can be argued that an outcome can be “read” or understood as a goal. During a press briefing in late March of 2020, Tegnell said that since the law guarantees freedom of movement, there would be no strict rules; instead, only advice would be given to the public.

In the same vein, protecting the economy was not made an explicit aim of the strategy, but it was hoped that avoiding lockdown would keep the economy running. Sweden is an open economy and heavily dependent on trade, and therefore its economy cannot escape any adverse impact of limited trade with the rest of world. In the context of a poised self-image, the underlying idea was that Sweden should do better than other countries in Europe, such as Italy, Spain and the UK, which were hard hit by the virus.

Generally, the guidelines issued by the government were varied and imprecise; for instance, initially gatherings of 500 were banned and later this number was reduced to 50 people. There was no explanation as to how these numbers were arrived at, especially during the early period when the science on coronavirus infection and transmission was evolving in different parts of the world. On the whole, the messages were left to the public to interpret for themselves. Advice given to the public was articulated in various ways and this did not make it any less ambiguous or confusing. For example Carlson, the Director General of PHA, clarified that “it is physical distance we are seeking, not social distancing […]. We should get together even if we shall not do it physically, talk to each other, support each other to get out of this”.25 Again, the advice was left open for the public to decipher the difference between social distancing and physical distancing. In any case, people in Sweden generally keep a distance from strangers in trains and public places. Keeping distance is part of the culture, but the change of terminology from social distancing to physical distancing can be misleading to the public.