Introduction

On a daily basis, adults may be called to play many roles, be it as an employee, spouse, parent, child, or elder caregiver. The growth of wage labour and capitalist industrialism has made it such that activities of economic production and social reproduction have become separated from one another, where work and family emerge as two unique domains of one’s adult life, each with distinct expectations. The multiple and often conflicting work and family roles hamper the balance and ability to fulfil expectations of each domain, thus giving rise to the conflict between work and family and resulting in negative consequences for both individuals and organizations (Netemeyer et al., 1996; Petts et al., 2021; Schieman et al., 2009). Over the years concerns about determinants and consequences of the conflict between work and family domains and the ability to maintain an appropriate balance between the two have intensified.

The literature on the conflict between work and family domains identifies work-family conflict (WFC) and family-work conflict (FWC) as distinct but related forms of inter-role conflict, where meeting obligations in the work (family) role makes it difficult by virtue of the need to meet obligations in the family (work) role given how people have fixed amounts of resources, i.e., time and energy, to distribute when work and family roles simultaneously occur (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985: 77). Work-family conflict is identified as “a form of inter-role conflict in which the general demands of, time devoted to, and strain created by the job interfere with performing family-related responsibilities” whereas FWC is identified as “a form of inter-role conflict in which the general demands of, time devoted to, and strain created by the family interfere with performing job-related responsibilities” (Netemeyer et al., 1996: 401). This conceptualization of WFC and FWC was retained in our study.

While recognizing the need for interventions to create a balance in work and family domains, organizations have introduced flex-work programmes as options for employees, such as telework (Hill et al., 1998; Kraut, 1989). The term telework or telecommuting is used to describe an alternate job arrangement in which one’s job can be carried out from any location other than the primary dedicated space provided by the employer and by using information and communication equipment to connect with others within and outside the organization (see Charalampous et al., 2019 for review). Although telework was foreseen as early as 1950, it became viable with the creation of personal computers and portable modems in the early 1970s, and initially tried and tested by organizations when fuel shortages arose during the Oil Embargo of the mid-1970s (see Hill et al., 1998). Telework has been identified as one of the best options for workplace flexibility (see Raghuram and Wiesenfeld, 2004 for review). Previous research support that telework reduces expenses for organizations in terms of maintenance costs, utilities and rent of the building and eliminates employees’ commuting time, allowing them to give back part of this travel time in the form of longer work hours for organizations (Gajendran and Harrison, 2007; Hill et al., 1998). Furthermore, some previous research has shown increased work effectiveness (Delanoeije and Verbruggen, 2020; Gajendran and Harrison, 2007; Hill et al., 1998) and improved work morale (Hill et al., 1998) due to greater flexibility in the location and timing of work. However, previous research also provides evidence that teleworking reduces the extent of upward, downward, and horizontal work communication (Ramsower, 1985) and increases the extent to which teleworkers experience feelings of isolation (Gajendran and Harrison, 2007). Most importantly, several previous studies suggest that the implementation of telework dramatically altered the ways in which roles of work and family domains interact leading to conflict (Charalampous et al., 2019; Eddleston and Mulki, 2017; Hill et al., 1998; Raghuram and Wiesenfeld, 2004). However, all these research studies were conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has continued to spread worldwide causing economic and social obstruction. Governments have enforced rigorous lockdowns and advised people to practice social distancing and stay at home as much as possible to mitigate the spread of the disease. This has triggered a seismic change with almost no advance warning in ways day-to-day business operations have been carried out. Whilst also having a spouse, children and/or other dependents in the house and with or without reasonable amenities at home, millions of employees worldwide were forced to deliver their fulltime jobs from home. Now, the term working from home has become more popular, being used now in conjunction with the term telework. In this context, and comparing with pre-pandemic period, millions of employees worldwide during the lockdown experienced how paid work in the form of working from home encroached on time and space of the family domain and dragged extreme amounts of their attention and energy resulting in WFC and FWC. In other words, developments due to the COVID-19 pandemic have dramatically challenged ways in which work and family domains interact (Fisher et al., 2020; Hertz et al., 2021; Petts et al., 2021; Reichelt et al., 2021). In the case of the corporate sector, although practically no one at all was prepared for a health crisis of this magnitude, the COVID-19 pandemic severely tested the capabilities of business leaders and organizational practices adopted in response (Martineau and Trottier, 2022; MTI Consulting, 2020).

Considering changes occurred in the nature of work over the last two decades, the recent literature identifies creative performance as a requirement from employees at all levels of the organizational hierarchy and working in various occupations across industries (Abstein and Spieth, 2014; Amabile, 2000; Oldham and Cummings, 1996; Shalley et al., 2009). Many or potentially all employees, who were traditionally not required to be creative at work, are now required to be creative (Abstein and Spieth, 2014; Shalley et al., 2009). This has resulted in an increase in research studies investigating factors affecting employees’ creative performance (refer to Shalley et al., 2009 for a review). Research studies such as Abstein and Spieth (2014) showed that conflict in work and family domains make it difficult for employees to engage in discretionary behaviour, such as creative performance. However, little is known about the conditions that promote or inhibit creative performance of employees working from home during COVID-19. Considering the aforementioned context and identifying employees’ creative performance as a desirable work outcome expected by organizations (as reviewed in detail in the next section), the present study investigated: 1) job conditions experienced by employees and their effect on WFC and FWC, and 2) whether WFC and FWC mediate the relationship between job conditions and employees’ creative performance. For the study, a sample of employees in white-collar or professional jobs who performed their fulltime jobs in the form of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic responded.

Since the world has emerged from the initial rapid response period to the pandemic, and organizations and employees have accustomed to working from home, the world may experience an explosion in the number of people working from home (Dingel and Neiman, 2020). It is also expected that, with the pandemic, working from home continues as a standard perk for employees worldwide (Bloom, 2020). Therefore, working from home, WFC and FWC, and achieving desirable work outcomes will continue to have significant strategic importance in the workplace, and may attract the attention of academics, researchers, employers, and policymakers. So far, there has been very little empirical research about effects of this burgeoning work form on employees and organizations. Therefore, our empirical investigation is expected to provide new knowledge and understanding about job conditions experienced by employees while working from home and antecedents and consequences of WFC and FWC.

Furthermore, this study was conducted in a South Asian country, Sri Lanka. Having been colonized by the Portuguese, Dutch, and British for the period spanning 1505 to 1948, the country reflects a combination of Asian values and Western practices. The country is identified as desirable for conducting business due to its highly literate workforce (over 92% in 2020) and since English is widely spoken. The populace perceive work as a way of living instead of a way of life, which influences their expectation of work practices. Characteristics of managers are at the higher end of the power distance continuum (refer to Wickramasinghe and Mahmood, 2018 for review). The organization-individual fit of cultural values in Sri Lanka demonstrates a positive association with organization-based self-esteem, a belief about an individual’s personal worthiness within an organization (Gardner et al., 2018). Although the country’s legal framework is a mix of Roman-Dutch Civil Law, English Common Law, and Customary Law, the Roman-Dutch Law regulates the employment relationship. Concerning labour protection, Sri Lanka has ratified all eight core Conventions of the International Labor Organization (ILO); the country’s labour standards are compatible with these. Sri Lanka provides maternity leave and nursing intervals for female employees. However, the country has not ratified ILO’s four Conventions that contribute towards harmonizing responsibilities of work and life domains, i.e., Home Work, Part-Time Work, Workers with Family Responsibilities, and Maternity Protection Conventions, and does not have provisions for these in the country’s labour standards (Sarveswaran, 2014). This context of the country underscores the importance of the present study to provide much needed diversity to empirical evidence on the conflict between work and family domains and its consequences.

1. Literature Review

1.1. Work-Family and Family-Work Conflict of Teleworkers - Before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic

The evidence for WFC and FWC in telework to date is inconclusive (see Gajendran and Harrison, 2007 for review). Still, the majority of the studies support the view that teleworkers experience conflict in work and family domains due to interference from work to family and family to work. These studies assert that job interference in performing family-related responsibilities and family interference in performing work-related responsibilities could occur more frequently in telework (Charalampous et al., 2019; Eddleston and Mulki, 2017; Raghuram and Wiesenfeld, 2004). The research in this line of reasoning supports the fact that telework does not clearly define physical boundaries and standardized work hours, which traditional office employees experience (Kraut, 1989; Olson and Primps, 1984; Raghuram and Wiesenfeld, 2004). For example, Raghuram and Wiesenfeld (2004) showed that employees who were engaged in telework extensively display work interference in family more than employees who were engaged in telework less extensively; they suggested that employees who were engaged in telework extensively may have difficulty in maintaining clear boundaries between the work and family domains of their lives. However, one of the main limitations of the studies conducted on telework before COVID-19 is that teleworkers were not homogenous in the amount of time they spend away from their regular workplace (see Hill et al., 1998; Raghuram and Wiesenfeld, 2004). In other words, in previous studies, teleworkers were not teleworking fulltime.

COVID-19 converted millions of employees into teleworkers overnight with the label of working from home. Many experienced problems with working from home fulltime since they had to perform job duties while located in places with no clear demarcations within the home and with a spouse, kids, or other dependents 24/7 in the house (Fisher et al., 2020; Hertz et al., 2021; Petts et al., 2021; Zamarro and Prados, 2021). That is, they experienced practically no clearly demarcated place within the home reserved for performing duties in the work domain and a clearly demarcated time set aside to attend to duties of the family domain. Hence, working from home required employees to be physically located in the home but psychologically or behaviourally involved in the job role; faced with the difficulty of transiting from family responsibilities to job role to deal with job demands, and vice versa. Some studies even provide evidence for increased workload from job responsibilities during the COVID-19 pandemic (MTI Consulting, 2020). Therefore, the COVID-19 pandemic has created a unique working from home context to understand WFC and FWC experienced by employees. Understanding their experience is of great importance because working from home is expected to intensify and continue after the COVID-19 pandemic. The current study investigated the extent to which job conditions experienced while working from home led to create WFC and FWC along with consequences pertaining to employees’ creative performance.

1.2. Job Conditions and Work-Family and Family-Work Conflict of Teleworkers

The literature provides evidence that job conditions operate as antecedents of conflict in work and family domains (Martineau and Trottier, 2022; MTI Consulting, 2020). Teleworkers have fewer opportunities to seek out job-related clarifications from supervisors and co-workers when compared with employees who are not remote; teleworkers’ feelings of remoteness and isolation and their reliance on lean communication media increase the likelihood of misunderstandings, uncertainty related to job-related expectations, insecure feelings, and distrust when compared to employees who are centrally located (Gajendran and Harrison, 2007). Studies such as Ramsower (1985) found that the amount of job variety is related to teleworker satisfaction. In addition, Raghuram and Wiesenfeld (2004) suggested that job-related ambiguity makes it more difficult for teleworkers to establish clear boundaries segmenting their activities, which leads to WFC and showed that employees who use telecommuting extensively are less likely to experience WFC if they know clear performance indicators and experience less ambiguity in their relationships with peers. Furthermore, Martineau and Trottier (2022) showed that the provision of job autonomy and job feedback can reduce the burden on family domains when performing job duties in the form of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, these studies suggest that clear and explicit job-related expectations give more confidence to teleworkers and make them “more capable of managing themselves to satisfy others’ expectations” (Raghuram and Wiesenfeld, 2004: 263).

Regarding work environment and technical support experienced by teleworkers, Ramsower (1985) found that workstation conditions and security were related to teleworker satisfaction. Hill et al. (1998) emphasized the importance of carefully choosing technical tools to fit with the particular job to be completed in the form of telework and speculated that selecting improper tools can adversely impact on employee productivity. The studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic highlight the importance of having enabling home infrastructure such as a workstation, posture-friendly seating, ventilation, lighting, and work environment ergonomics for effective delivery of job activities in the form of working from home (MTI Consulting, 2020). Studies such as Purwanto et al. (2020) stress the importance of employees working from home having necessary software to manage their job activities, a reliable internet connection, and consistent connectivity to co-workers and organizational services for effective performance of job activities during the pandemic. Purwanto et al. (ibidem) also reports incidences of employees absorbing internet and electricity costs associated with working from home by themselves during the pandemic. Based on the above reviewed literature, it is hypothesized: H1a) Adequate job conditions for working from home negatively related to WFC; H1b) Adequate job conditions for working from home negatively related to FWC.

1.3. Creative Performance

Creativity describes characteristics of novelty, appropriateness and usefulness that are valuable for the performance of tasks at hand (Amabile, 2000; Shalley et al., 2009; Wang and Netemeyer, 2004). For example, Wang and Netemeyer (2004: 806) showed that “creative performance is exhibited in many aspects of task accomplishment such as in generating and evaluating new solutions for old problems, seeing old problems from a different perspective, defining and solving a new problem, or detecting a neglected problem”. For most employees at all levels of the organizational hierarchy and engaged in different types of jobs across industries, creative performance represents an inherent requirement that is, in general, not prescribed in their formal job descriptions (Abstein and Spieth, 2014; Oldham and Cummings, 1996; Shalley et al., 2009). Still, employees are expected to be creative and provide the raw materials needed for change and innovation within organisations for long-term survival (Amabile, 2000; Moulang, 2015; Oldham and Cummings, 1996). The literature shows that employees’ creative performance should be studied with respect to the interaction between the individual and the environment (Amabile, 2000; Shalley et al., 2009; Wang and Netemeyer, 2004). In this regard, Shalley et al. (2009) and Wang and Netemeyer (2004) provide evidence that the context of work performance is an imperative consideration when studying creative performance. Therefore, building on the previous studies reviewed above, the present study investigated whether WFC and FWC constrain creative performance. Therefore, it is hypothesized: H2a) WFC negatively related to creative performance; H2b) FWC negatively related to creative performance.

The aforementioned H1 predicts the association between job conditions and WFC and FWC. The hypothesis H2 predicts the association between WFC and FWC creative performance. Based on the previous research that suggest the context of work performance is a vital aspect in studying creative performance (such as Shalley et al., 2009; Wang and Netemeyer, 2004), and to make the mediation hypotheses complete, it is proposed: H3) WFC and FWC mediate between job conditions and creative performance.

2. Methodology

2.1. Measures

WFC and FWC were measured using the scale developed by Netemeyer et al. (1996). Each scale consists of five items denoting the bi-direction nature of conflict in work and family domains. These item measures are shown in Table 1. Job conditions were measured using the 19-item scale developed for the study. The measures were on a five-point Likert response scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. These item measures are shown in Table 2. Creative performance was measured using the 3-item scale developed by Oldham and Cummings (1996). These item measures are shown in Table 3.

2.2. Sample of the Study and Method of Data Collection

The target population is employees engaged in white-collar or professional fulltime jobs on a permanent basis in private sector organizations and working from home during the COVID-19 lockdown in Sri Lanka. Convenience and snowball sampling methods were used in the study. A total of 380 valid responses were received for the online survey questionnaire, which was developed using Google Forms and the link of which was distributed via email and social media. The questionnaire protected the anonymity of the participants of the survey. The questionnaire was in English, which is considered as a national language in Sri Lanka. Prior to the distribution of the questionnaire, it was pre-tested with a sample of employees who were not part of the final sample.

Regarding the characteristics of respondents, 62% were in the 20-30 year old age range, 35% were from 31 to 40 years of age, and 3% were 41 to 65 years old. Of the respondents, 53% were females while 47% were males. 42% identified as single (including never married, separated, divorced, and widowed), 40% identified as married with children, and the remaining 18% identified as married without children. Of the respondents, 36% identified their highest education qualification as a secondary school diploma while the remaining 64% had a Bachelor’s degree or higher level of education qualification. Overall, 67% of the respondents were engaged in service sector firms and the remaining 33% came from the manufacturing sector, holding a wide spectrum of office jobs. Regarding the years of experience with the current firm, 63% had up to 5 years of work experience while the remaining had 5 years or more of work experience.

2.3. Methods of Data Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis using Principal component factor analysis Varimax rotation was performed on the variables for appropriate internal consistency reliability, factor structure, convergent validity, discriminant validity, and construct reliability (CR). Convergent validity was measured by average variance extracted (AVE) and discriminant validity was measured by the square root of AVE. Variables were also tested for common method variance using Harman’s single-factor test in SPSS, and the percentage was less than 50. Considering the complexity of the model, composite mean scores for the variables were computed for later analyses (refer to Bobko et al., 2007). The proposed model was tested using statistical techniques of multivariable analysis, which allows for determining independent contributions of each explanatory variable on the response variable (Reboldi et al., 2013). For this, structural equation modelling was performed using AMOS. The results were assessed based on normed chi-square statistic (χ2/df) and fit indices of the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

3. Results

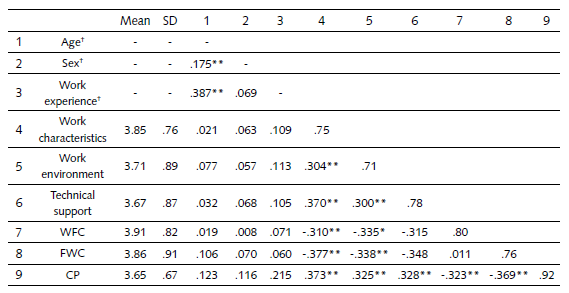

Table 1 shows the results of factor analysis for WFC and FWC. The factor analysis resulted in three factors which explained 72% (71.76) of the variance. Table 2 shows the results of factor analysis for job conditions. The factor analysis resulted in three factors, which explained 67% (66.52) of the variance. These three factors were named as work characteristics, work environment and technical support. Table 3 shows the results of factor analysis for creative performance. The factor analysis resulted in one factor. Table 4 shows descriptive statistics and correlations between variables.

Table 1 Work-Family Conflict and Family-Work Conflict

| Item | WFC | FWC |

|---|---|---|

| The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life | .869 | |

| The amount of time my job takes up makes it difficult to fulfil family responsibilities | .859 | |

| Things I want to do at home do not get done because of the demands my job puts on me | .817 | |

| Due to work-related duties, I have to make changes to my plans for family activities | .729 | |

| My job produces strain that makes it difficult to fulfil family duties | .702 | |

| Family-related strain interferes with my ability to perform job-related duties | .867 | |

| My home life interferes with my responsibilities at work such as getting to work on time, accomplishing daily tasks, and working overtime | .847 | |

| I have to put off doing things at work because of demands on my time at home | .776 | |

| The demands of my family or spouse/partner interfere with work-related activities | .665 | |

| Things I want to do at work don’t get done because of the demands of my family or spouse/partner | .586 | |

| Eigenvalue | 3.398 | 3.278 |

| % of Variance | 38.98 | 32.78 |

| Cronbach’s α | .890 | .837 |

| AVE | .637 | .571 |

| CR | .897 | .867 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Table 2 Job Conditions

| Item | Work characteristics | Work environment | Technical support |

|---|---|---|---|

| My immediate supervisor trusts my job performance during work from home period | .871 | ||

| My job allows me to participate in online collaborative activities to maintain connections with colleagues | .849 | ||

| I am allowed to work on a flexible work schedule during work from home period | .840 | ||

| I have freedom to make suggestions to enhance the way we work during work from home period | .821 | ||

| The way I performed my job has been monitored during work from home period | .787 | ||

| I do not feel isolated from my colleagues during work from home period | .776 | ||

| I have control over what I am doing in my job during work from home period | .745 | ||

| I have adequate job tasks to carry out during work from home period | .591 | ||

| My job allows me to take decisions during work from home period without depending on co-workers | .583 | ||

| I am happy with the opportunity to work from home during the COVID-19 pandemic | .516 | ||

| I can carry out my work without disturbances coming from nature (thunderstorms) and sudden power failures during work from home period | .796 | ||

| My workplace has introduced employee-friendly policies to carry out work during work from home period | .779 | ||

| I can decide when to take my breaks (e.g., lunch and tea times) during work from home period | .701 | ||

| Physical work environment of my home helps me to carry out work effectively during work from home period | .666 | ||

| I have not been pressurized due to unrealistic daily deadlines during work from home period | .664 | ||

| I can carry out my work without disturbances coming from other persons living in my home during work from home period | .640 | ||

| My workplace has provided me with required data facilities (e.g., Wi-Fi) to perform work during work from home period | .816 | ||

| My workplace has provided me with appropriate equipment and technical support (e.g., laptop/computer, router/internet facility, software) to carry out work during work from home period | .791 | ||

| My workplace has provided me with appropriate channels to share information (e.g., Skype, Slack, MS Teams, email) during work from home period | .744 | ||

| Eigenvalue | 6.243 | 3.572 | 2.823 |

| % of Variance | 32.86 | 18.80 | 14.86 |

| Cronbach’s α | .951 | .800 | .830 |

| AVE | .559 | .504 | .615 |

| CR | .925 | .858 | .827 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Table 3 Creative Performance

| Item | Creative performance |

|---|---|

| The work I produce is creative | .939 |

| The work I produce is original | .944 |

| The work I produce is novel | .874 |

| Eigenvalue | 2.536 |

| % of Variance | 84.53 |

| Cronbach’s α | .908 |

| AVE | .846 |

| CR | .943 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Table 4 Correlation

Notes: † Binary coded variables, **p< 0.01; diagonal entries, square root of AVE; off-diagonal entries, correlations between constructs. Source: Elaborated by the authors.

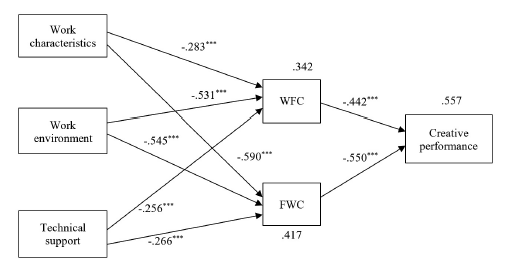

The results of CFA were used to evaluate the causal relationships proposed in the study, which are shown in Figure 1. As shown in the figure, work characteristics (β = -.283, p < 0.001), work environment (β = -.531, p < 0.001) and technical support (β = -.256, p < 0.001) together identified as job conditions significantly negatively related to WFC, supporting H1a. In addition, work characteristics (β = -.590, p < 0.001), work environment (β = -.545, p < 0.001) and technical support (β = -.266, p < 0.001) significantly negatively related to FWC, supporting H1b. Furthermore, WFC significantly negatively related to creative performance (β = -.442, p < 0.001), supporting H2a; FWC significantly negatively related to creative performance (β = -.550, p < 0.001), supporting H2b. Finally, the model proposed in the study satisfies the model fit criteria of χ2/df value of 1.89, TLI of .847, CFI of .861 and RMSEA of .076. This supports H3 that WFC and FWC mediate between job conditions and creative performance. Figure 1 also shows the values of coefficient of determination. The coefficient of determination of 0.417 as opposed to 0.342 suggests that job conditions (work characteristics, work environment and technical support) have comparatively higher effect on FWC. Further, the coefficient of determination of 0.557 suggests job conditions, WFC and FWC account for 56% of the variation of creative performance.

4. Discussion of Findings and Implications for Theory and Practice

Several decades ago, the model of teleworking was introduced to the corporate world as an option for employees to balance their roles in work and family domains, under the umbrella of workplace flex-work arrangements (refer to Hill et al., 1998). However, many of the employees who enjoyed this option prior to the pandemic performed their job tasks in the form of telework for few hours per day or few days per week (refer to Hill et al., 1998; Raghuram and Wiesenfeld, 2004). In contrast to this practice, due to the COVID-19 pandemic millions of employees have been made to perform their fulltime job tasks in the form of working from home. Since the COVID-19 pandemic is recent and the understanding of its repercussions are still unclear, empirical studies about workplace practices introduced because of the pandemic are valuable. When the corporate sector predicts that the working from home model will continue as a standard perk for employees for a foreseeable future, understanding about working from home for employees and organizations are very important. Using a sample of employees in white-collar or professional jobs who performed their fulltime jobs in the form of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic in Sri Lanka, we investigated associations between job conditions experienced during working from home, experiences of WFC and FWC and the effect of these on their creative performance. The results suggest that employees in the working from home mode in delivering their fulltime job roles during the pandemic had experienced more responsibilities than time would allow, which hampered their ability to perform their role expectations in work and family domains, thus giving rise to WFC and FWC. We presented evidence suggesting that adequate job conditions in terms of work characteristics, work environment and technical support reduce WFC and FWC and reduce negative effects on their creative performance. The findings also showed that both WFC and FWC mediate the relationship between job conditions and employees’ creative performance. As discussed in the following sections, our findings have several implications for theory and practice.

4.1. Contribution of the Finding to the Literature

Our research makes a novel contribution to the existing literature in several spheres. First, the pre-pandemic research on telework recognizes that it enabled employees to perform job tasks outside traditional office hours and office space (refer to Charalampous et al., 2019; Hill et al., 1998). The majority of research on interactions between work and family domains provide evidence that doing fulltime paid work at home while experiencing distractions to physical and temporal boundaries between work and family leads to WFC and FWC (refer to Charalampous et al., 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic has, seemingly overnight, dramatically changed how people live their lives and do their work for living. Working from home while locating 24/7 at home during the pandemic dramatically altered the ways in which the roles of these two domains interact; employees found participating in fulltime office work in the form of working from home is difficult since they have fixed amounts of time and energy to distribute between work and family roles (refer to Fisher et al., 2020; Hertz et al., 2021; Petts et al., 2021; Reichelt et al., 2021; Zamarro and Prados, 2021). Although academic, research and practitioner communities have called for empirical evidence that addresses employees’ wellbeing and productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic, empirical studies that investigated the effects of job conditions and WFC and FWC on creative performance while delivering fulltime job tasks in the form of working from home is scarce. The findings of our study provided empirical evidence that job conditions could create overwhelming situations in meeting expectations of work and family domains that could lead to WFC and FWC, which could have unfavourable consequences for organizations by impacting on employees’ creative performance. We believe that our study is novel and adds to a growing body of knowledge about the organization practice of delivering fulltime job tasks in the form of working from home, which have been introduced because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Second, although the pre-pandemic literature on competing demands of work and family domains distinguishes between WFC and FWC, the majority of empirical research focused on WFC consider it as the most prevalent form of the two (refer to Abstein and Spieth, 2014). In addition, the pre-pandemic studies showed that WFC has more severe consequences for individuals and organizations than the other (refer to Raghuram and Wiesenfeld, 2004). Adopting the distinction made in the literature, we investigated the bidirectional phenomenon of the conflict, which includes work conflicting with family and family conflicting with work. Our results suggest that perceptions of both WFC and FWC are associated with job conditions experienced by employees while working from home and that adequate job conditions reduce both types of conflict. Specifically, our results suggest that the effect of job conditions on family interference in work is more influential than on work interference in family. This finding is contradictory to many pre-pandemic researches conducted on teleworkers. For example, Raghuram and Wiesenfeld (2004) showed that favourable work-related factors reduce WFC but not FWC. Our results can be expected since the pre-pandemic research was not on employees who performed their fulltime job roles in the form of working from home while being at home 24/7, as during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is possible to argue that if employees were not delivering their fulltime job roles in the form of working from home while being 24/7 at home, the family domain of their lives could be more salient when they are at work.

Third, we systematically investigated the job conditions experienced by employees when delivering the fulltime job role in the working from home mode during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the possibility that job conditions contribute to WFC and FWC, and as a result, to employees’ creative performance at work. We showed that employees derive a greater benefit from favourable work characteristics, work environment and technical support that were identified as job conditions during working from home in minimizing the experience of both WFC and FWC. It is expected that the number of people working from home will climb sharply once the COVID-19 pandemic passes. The identification of job conditions as significant antecedents of WFC and FWC of employees delivering fulltime job role while located at home makes an important contribution, i.e., job conditions that are under the control of organizations will continue to be a main source of WFC and FWC.

Fourth, employees’ creative performance is critical in organizations as it can have substantial impact on organizations’ success. Although a growing body of research in recent times investigated the conditions that promote creative performance in employees, we are unaware of research studies that are focused on job conditions, WFC and FWC and creative performance when performing job duties in the context of the pandemic, which is the scope of the present study. Our results demonstrate that favourable job conditions have the possibility of reducing both WFC and FWC, and the overall effect of lowering undesirable effects of WFC and FWC on creative performance.

4.2. Implications of the Finding to Practice

As pointed out by Bloom (2020), even after the COVID-19 pandemic, mass working from home is here to stay; the world will see this practice proliferate in dramatic fashion. Organizations and individuals have already passed the initial response period and have already accustomed to this practice. Therefore, possibilities to continue the working from home initiative for the foreseeable future is much easier. We inclined to view, on the one hand, that the COVID-19 pandemic has shifted the conversation about possible future strategies of work or the workplace into the present. On the other hand, organizations should develop effective strategies to create resilience for possible future crises. We find that the implications of our study to practice must be evaluated from these two perspectives, and our results hold several implications for organizations that see working from home as an opportunity for change and intend to continue with this initiative.

The findings of the study provided evidence that job conditions significantly affect employees’ perceptions of work interference with family and family interference with work. Still, the job conditions employees have experienced while working from home appeared to be under organizations’ control. Specifically, organizations can take steps to provide favourable work characteristics, work environment and technical support for employees to work from home. Organizations should carefully select and supply appropriate technical tools and communication media to fit with the particular job to be performed through working from home. The provision of adequate and favourable job conditions have been shown to be beneficial in reducing both WFC and FWC and reducing negative consequences on employees’ creative performance. In addition, the findings highlight the importance of keeping employees continuously in the loop to maintain their concentration on work activities. Training and development programmes organized time to time for employees and their supervisors on social and psychological aspects, such as self-efficacy or changes required for effective delivery of job tasks in the form of working from home could be beneficial for employees as well as organizations. Overall, the findings of the present study provide sufficient scope for practitioners and policymakers to imagine how to face the new normal through effective workplace strategies and policy initiatives.

Conclusion, Limitations of the Study and Future Research

As the dynamics of the family domain and workplace have changed over the last few months, forever due to the pandemic and mass introduction of working from home, increased attention must be given to interactions between work and family domains and sources of conflict, and the resulting consequences. This study responded to the urge to examine the antecedents and consequences of WFC and FWC of employees who delivered their fulltime jobs in the form of working from home while being located 24/7 at home during the pandemic. The study was conducted in a South Asian country, Sri Lanka. The context makes a valuable addition to most of the scholarly work available in the West. The study showed that favourable job conditions provided by organizations that were experienced by employees while working from home have significant effect in lowering WFC and FWC, which in turn reduces negative effects on their creative performance. We believe that very few empirical studies like ours may have been conducted with the scope of COVID-19 pandemic, working from home policy, WFC and FWC, and valuable organizational outcomes expected from all employees irrespective of their job role, like creative performance. Therefore, the findings have several theoretical and practical implications as discussed in the previous sections.

There are few limitations of our study. First, the present study used cross-sectional research design and used self-reported measures to assess the variables under study. For example, future research could consider obtaining an immediate supervisor’s assessment of employee’s creative performance as suggested by some creativity scholars such as Amabile (2000) in contrast to self-report creativity propagated by Shalley et al. (2009) and Wang and Netemeyer (2004). Second, the study relied on a survey questionnaire and quantitative data analysis methods. Multi-method data collection and multi-methods for data analysis, i.e., quantitative and qualitative, could reduce some of the limitations of our study. Third, the sample of the present study included employees engaged in white-collar or professional jobs across a wide spectrum of manufacturing and service sectors. The methods we used are convenience and snowball sampling. As such, future research could find mechanisms to pool respondents using probability sampling methods for greater accuracy. The present study suggests exciting avenues for future studies on practices used to facilitate working from home in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The strategies used could vary by the nature of the business such as multi-nationals, large corporations, and small and medium-sized enterprises as well as by business sectors such as banks. In addition, future research could introduce possible moderators such as individual attributes in explaining WFC and FWC. For example, research studies such as Hertz et al. (2021) and Zamarro and Prados (2021) provide evidence for the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on women as opposed to men in terms of higher levels of psychological distress and work-life challenges. However, some other studies such as Petts et al. (2021) and Fisher et al. (2020) provide evidence that the pandemic facilitated a push towards egalitarianism in domestic duties. These findings suggest the need of more empirical studies on the gendered implications of the pandemic on the conflict between work and family domains while working from home.

Edited by Scott M. Culp