Introduction

Much like Tolstoy’s unhappy families, each unequal country is unequal in its own way. This does not just mean that some countries are more unequal than others, which is an obvious fact; it also means that the qualitative patterns of socioeconomic inequality, as well as the mechanisms which bring about that inequality and those which curb it, differ from country to country. Such country-specific patterns and mechanisms are not entirely endogenous, of course. Rather, they are the result of a historically developed interplay between internal and external political and economic dynamics: the productive specialisation pattern and growth regime; the characteristics and institutions of the labour, product and financial markets; the development, consolidation and in some cases rolling-back of the welfare state; the ebb and flow of domestic politics; the modes of subordination to supranational regulatory bodies and international financial agents. All these factors - and more - matter, in different ways, in different contexts.

The previous paragraph synthesizes the first key insight underpinning the concept of regimes of socioeconomic inequality, as proposed by Robert Boyer (2015a, 2015b, 2016) in the tradition of the Regulation School. Specifically, this author defines inequality regimes as a particular combination of inequality-generating processes articulated in an idiosyncratic way in a specific time and place (Boyer, 2015b: 156). Boyer has himself been a leading proponent of the Regulation School since the 1970s, alongside Michel Aglietta, Alain Lipietz and others within and outside France (cf. Boyer, 2015b). An offshoot of Marxist political economy with especially strong institutionalist influences, the Regulation School originally emerged out of the particular historical juncture of the crisis of Fordism and the intention to explain and interpret that crisis - and as such was characterised from its inception with a particular concern with the concrete, the institutionally specific and the historically contingent, especially by contrast with other more general and abstract approaches influenced by Marxism. Thus, rather than concerning itself primarily with the laws of development of capitalism in general, authors in the Regulation tradition have tended to focus on particular capitalist economies/social formations and particular historical periods, with their characteristic regimes of accumulation and modes of regulation. With its emphasis on the diversity and complementarity of different capitalist social formations over time and across space, the Regulation School has been a central contributor to the idea of different varieties of capitalism, an idea explored also by such related approaches as the Social Structures of Accumulation School (Kotz et al., 1994; McDonough et al., 2010) or the more recent and eponymous Varieties of Capitalism approach (Hall and Soskice, 2001).

When applied to the study and analysis of inequality, a field which has seen massively expanding interest in recent decades (cf. Wilkinson and Pickett, 2009; Stiglitz, 2012; Piketty, 2014; Atkinson, 2015; Milanović, 2016, among others), the implication is clear: rather than emphasising one single overarching process or tendency prevailing across time and space - as exemplified by Simon Kuznets’s (1955) inverted-U or Thomas Piketty’s (2014) r>g hypotheses -, it is more fruitful to consider the possibility that different types of inequality-enhancing or inequality-limiting processes may prevail and indeed combine in different ways in different contexts. Some economies may experience inequality increases of the more traditional Kuznets type, involving initial processes of industrialisation, commodification and class differentiation; others may experience inequality surges in the context of post-industrial finance-led growth regimes. In some contexts, inequality may be kept in check primarily by the redistributive action of the government - taxes, social transfers and provision of public services -, while in other contexts such a curb may arise at the level of the primary income distribution, for instance as an effect of a significant increase in education levels reducing wage premia and wage inequality. In other words, inequality tendencies do not operate in a vacuum: they are structurally interrelated with an economy’s accumulation and welfare regimes, and further influenced by a variety of more contingent factors.

In addition, the inequality regimes of different economies are internationally integrated and often complementary - in the sense that they provide each other with a degree of stability which would be impossible for each to achieve in isolation (Boyer, 2015a, 2016). Economies with massive external surpluses may avoid stimulating internal demand (and reducing inequality) by recycling those surpluses as capital outflows to debtor economies. The latter may rely on such inflows of capital to fuel (at least temporarily) debt-led growth, which often also serves to mask increasing internal inequality. Commodity exporters are provided with additional fiscal space with which to address poverty and inequality during the peak phases of commodity cycles, which in turn are associated with growth, and typically rising inequality, in rapidly industrialising countries. And so on and so forth. The point is that an inequality regime does not stop at a country’s borders - it is integrated with those of other economies through various channels, with implications for the analysis.

The historically contingent and institutionally specific character of inequality regimes implies that they must be examined in the concrete rather than through the lens of a single abstract theoretical process. Nevertheless, as a starting point for that concrete examination, Boyer (2015b: 157) lists five major inequality-generating processes which are likely to be found to various degrees in different contexts, and therefore to constitute a central part of the inequality regime in question: (i) the capital-labour conflict; (ii) classification struggles (distinct from class struggles) driven by differences in education, training and access to better-paid jobs; (iii) the rentier-debtor antinomy, especially in a context of financialisation; (iv) the social arbitration between solidarity and individualism, particularly in the fiscal domain; and (v) the extent of primary good provision (health, education, housing, etc.) by the welfare state.

This paper is an attempt to apply the insights and methods of this approach to the case of Portugal, a small semiperipheral economy integrated into the European Union (EU) and the Eurozone, which came out of an authoritarian dictatorship in 1974 into a brief period of high-intensity popular democracy that allowed for the development and consolidation of an important but incomplete welfare state, and which subsequently transitioned into a period of neoliberalisation and financialisation in the context of European integration. With this aim in mind, the remainder of this paper looks first at the broad empirical patterns of inequality in this country and how they have evolved over time (section 1), and then proceeds to discuss the key inequality-enhancing and -limiting mechanisms at work in this social formation which account for those empirical patterns (section 2), before wrapping up with the main conclusions in the last section.

1. Portugal’s Inequality Regime: Empirical Patterns1

1.1. Current Income Inequality Levels

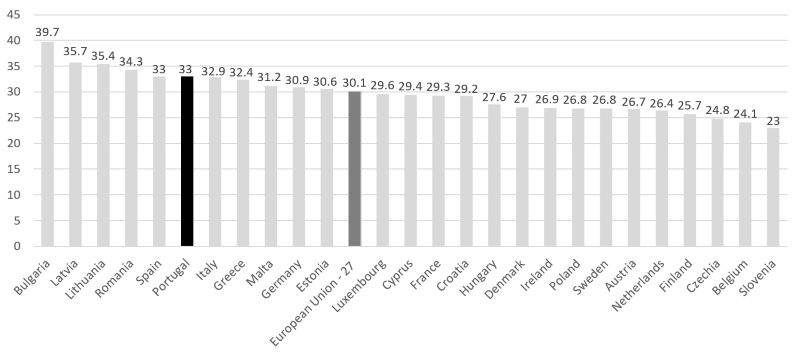

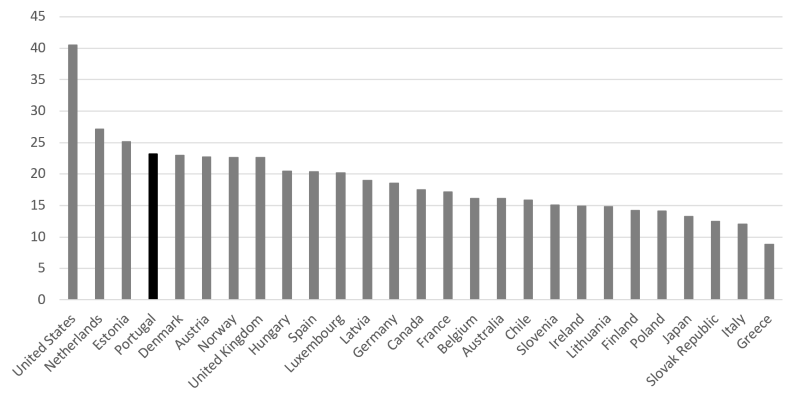

The most commonly used data on income inequality in Portugal originate in the survey-based Statistics on Income and Living Conditions, which are harmonised at the European level (EU-SILC). These include two of the most widely used income inequality statistics, the Gini coefficient and the S80/S20 (ratio of the income shares of the top and bottom quintiles), both of which consider equivalised disposable income (i.e. total income after taxes and other deductions, adjusted for household composition) (Figures 1 and 2). In 2021, Portugal’s Gini index was 33.0%, higher (i.e. more unequal) than the EU-27 average of 30.1%. It was 31.9% in 2019 compared to 30.2% in the EU as whole, which suggests that the pandemic and lockdowns had a greater inequality-enhancing effect in Portugal than in the rest of Europe. The same conclusion holds when we look at the S80/S20 ratio: 5.66 in Portugal in 2021 (5.16 in 2019) compared to 4.97 in the EU-27 (4.99 in 2019) (Eurostat, 2023a, 2023b).

Figure 1 Gini index (%) in 2021 in the EU-27, Portugal, and 25 other EU countries (data for Slovakia not available). Source: Elaborated by the author from data collected via Eurostat (2023a).

Figure 2 S80/S20 ratio in 2021 in the EU-27, Portugal, and 25 other EU countries (data for Slovakia not available). Source: Elaborated by the author from data collected via Eurostat (2023b).

These levels are low by global standards. The Gini index is higher than 40% in most African and Latin American countries and higher than 50% in some of those countries; and has hovered above 40% in the United States in the last three decades (World Bank, n.d.). In the European context, however, Portugal is clearly among the group of the most unequal countries, alongside a few other Southern European and Eastern European countries (Figures 1 and 2).

1.2. Income Inequality Trends

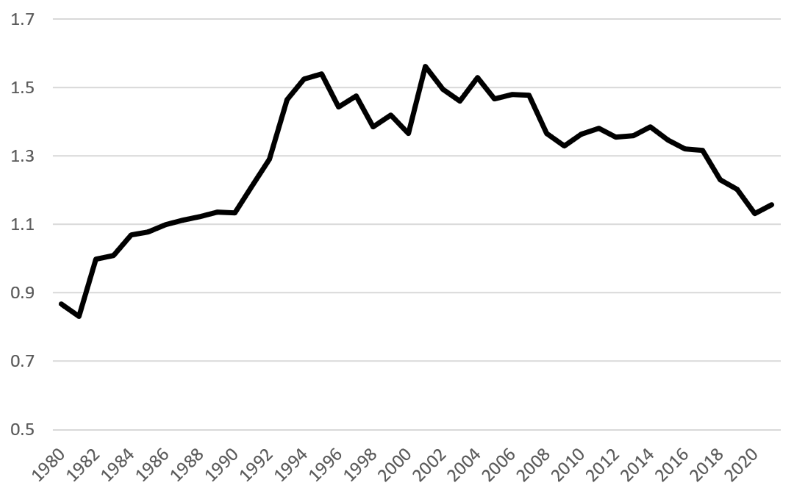

While few sources provide homogeneous data covering the entire period between the Portuguese democratic Revolution in 1974 and the present day, the joint analysis of data from Carlos Farinha Rodrigues (2007), Facundo Alvarado (2010), Jordi Guilera Rafecas (2014), Eurostat (2023a) and the World Inequality Database (WID, n.d.), variously based on tax, administrative microdata (“Quadros de pessoal”) and/or EU-SILC survey data, indicates that income inequality underwent a considerable increase in the 1980s and 1990s, rising rapidly from the low levels of the post-revolutionary period to record highs, before initiating a long-term decline around the turn of the millennium. The ratio of the income shares of the top 10% relative to the bottom 50% nearly doubled in the years 1981-1994, but declined gradually to more moderate levels after 2000 (Figure 3). The Gini index and S80/S20 ratio data for the 1994-2020 period, for which data are available, corroborate the finding of a relative decline in income inequality after 2000, albeit interrupted during the Eurozone (2010-2013) and COVID-19 (2021) crises (Figure 4). However, this decline was not enough to bring income inequality back to its levels of the 1970s and early 1980s, nor, as we have seen previously, to take Portugal out of the group of most unequal countries in Europe.

Figure 3 Post-tax S90/S50 ratio in Portugal, 1980-2021. Source: Author’s calculations based on data via WID (n.d.).

Figure 4 Gini index (%, line, right axis) and S80/S20 ratio (columns, left axis) of equivalised disposable income in Portugal, 1994-2020. Note: Series breaks in 2001 and 2003. Source: Elaborated by the author from data collected via PORDATA (2023a, 2023b).

1.3. Top Incomes

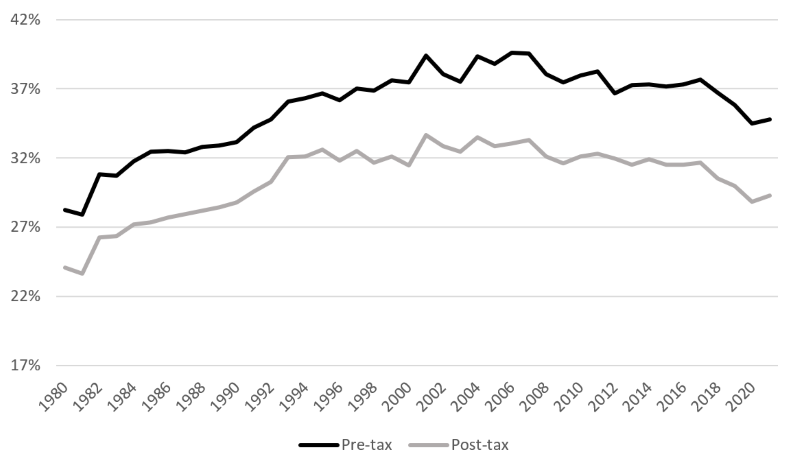

Consistently with the previous fact, and indeed contributing to it, we find that the income share of the top percentiles in the income distribution underwent a substantial increase between the early 1980s and early 2000s (Alvarado, 2010). This is well illustrated by the pre-tax share of national income of the top 1%, which nearly doubled over twenty years, from 6.4% in 1981 to 11.2% in 2001, and has remained around 10%-11% ever since, according to the WID (Figure 5). The pre-tax share of the top 10% underwent a similar though somewhat less pronounced increase until the early 2000s and a moderate decline in the last 20 years (Figure 6). A comparison with the post-tax income shares of the top 1% and top 10% in Figures 5 and 6 suggests an increase over time of the moderating influence of the tax system: the difference between the pre- and post-tax shares of national income of the top 1% was 1.7 percentage points (p.p.) in 1980 and 3.3 p.p. in 2018.

Figure 5 Pre- and post-tax shares of national income of the top 1% in Portugal, 1980-2021. Source: Elaborated by the author from data collected via WID (n.d.).

Figure 6 Pre- and post-tax shares of national income of the top 10% in Portugal, 1980-2021. Source: Elaborated by the author from data collected via WID (n.d.).

1.4. Bottom Incomes

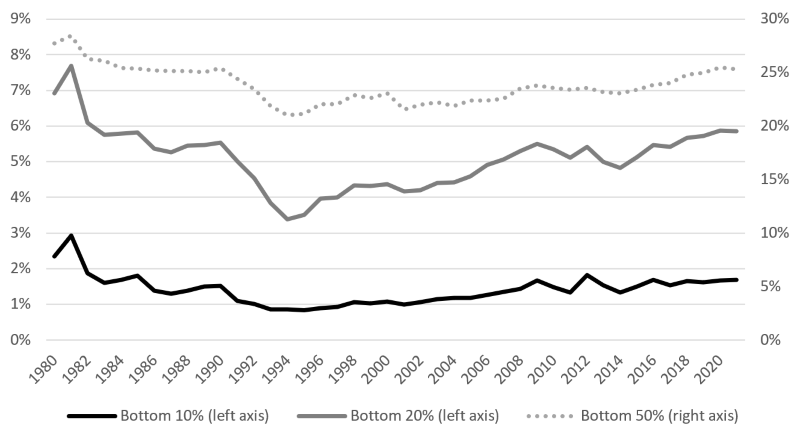

In a pattern consistent with what we have seen so far, we also find that the bottom income groups in Portuguese society lost the most in relative terms between 1980 and the early 2000s and subsequently experienced a relative recovery in the last two decades. This is apparent in the trajectory of the income share of the bottom 50%, which dropped from around 28% in 1980 to 21% in 1995, before recovering to around 25% in the present (Figure 7). A similar pattern holds for the bottom decile and bottom quintile, according to WID (n.d.) data. Once again, this is consistent with the overall picture of a pattern of inequality which increased enormously between 1980 and the late 1990s both at the top and at the bottom, and which was then partly reduced in the subsequent two decades also at the top and at the bottom (although the very top 1% evaded this correction).

Figure 7 Post-tax shares of national income of the bottom 10%, 20% and 50% in Portugal, 1980-2021. Source: Elaborated by the author from data collected via WID (n.d.).

1.5. Wealth Inequality

Wealth inequality in Portugal is much higher than income inequality. While this is a common pattern across most countries, the extent of such inequality is impressive, and one of the highest among European and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (Figure 8). The Gini index of the distribution of net personal wealth (assets minus liabilities) was estimated by the WID at 76% in 2021, compared to 33% for equivalised disposable income as estimated by the Eurostat (see section 1.1). Remarkably, this is an aspect in which there seem to be significant differences among Southern European countries, making it difficult to speak of a homogeneous inequality regime typical of these countries: the share of wealth owned by the wealthiest 1% is estimated at 23% in Portugal, 20% in Spain, 12% in Italy and 9% in Greece (OECD, 2021).

Figure 8 Share of wealth owned by the top 1%, latest available year. Source: Elaborated by the author from data collected via OECD (2021).

While there are obvious bidirectional flow-stock linkages between income and wealth, some factors affect these two aspects differently, allowing for diverging trajectories. Differently from income inequality, the available data on wealth inequality suggests its relative stability between 1995 and 2010, with a Gini index hovering around 74%, followed by an increase in 2010-2013 to 77%, remaining relatively constant thereafter (WID, n.d.). This finding is corroborated by the data from the OECD Income and Wealth Distribution database on the wealth shares of the top 1%, 5% and 10%, all of which increased consistently between 2010 and 2017 (Table 1). Thus, while the previous sections suggested a relative moderation of income inequality over the last decade, these data show considerable wealth accumulation by the very wealthiest households in Portuguese society in that period: note, in Table 1, that the wealth share increases by the top 5% and top 10% are more than entirely accounted for by the top 1%. This process of emergence and consolidation of a small group of super-rich individuals and households is illustrated by other sources, such as the Credit Suisse Research Institute’s (2022) Global Wealth Report (Table 2).

Table 1 Wealth shares of the top 10%, 5% and 1% in Portugal, 2010, 2013 and 2017

| 2010 | 2013 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top 10% | 51.4 | 53.0 | 53.9 |

| Top 5% | 39.3 | 40.9 | 41.6 |

| Top 1% | 19.6 | 22.1 | 23.2 |

Source: Elaborated by the author from data collected via OECD (2021).

Table 2 Number of individuals in Portugal belonging to various high net wealth classes, 2021

| Number of individuals | Percentage of total population | |

| 1-5 M€ | 150,208 | 1.46247% |

| 5-10 M€ | 6,347 | 0.06180% |

| 10-50 M€ | 2,345 | 0.02283% |

| 50-100 M€ | 57 | 0.00055% |

| 100-500 M€ | 41 | 0.00040% |

| 500+ M€ | 8 | 0.00008% |

Source: Elaborated by the author from data collected via Credit Suisse Research Institute (2022).

1.6. Poverty Rates

The at-risk-of-poverty rate commonly used in Portugal and across Europe (the share of persons with an equivalised disposable income below 60% of the national median) is a relative, not absolute, indicator. This takes nothing away from its importance for discussions around poverty, which is inherently contextual and relational. But it does mean that this indicator is equally relevant for analyses of inequality: in reality, the at-risk-of-poverty rate indicator is an inequality indicator which focuses on the left-hand side of the income distribution.

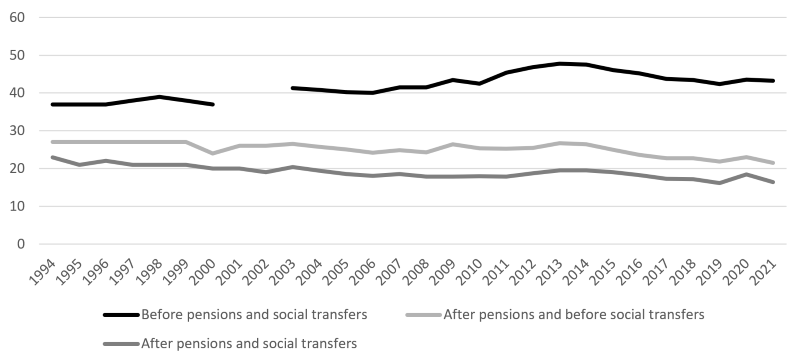

In the nearly three decades between 1994 and 2021, for which comparable data are available (albeit with series breaks), we find a remarkable trajectory: a worrying long-run increase in the poverty rate before pensions and social transfers, only partially reversed in the last decade (37% in 1994, 41% in 2004 and up to a maximum of 48% in 2013 before dropping to 43% in 2021), alongside a long-run decrease in the poverty rate after pensions and social transfers (from 23% in 1994 to slightly above 16% in 2022). This is an important feature of Portugal’s inequality regime: a tendency for the primary income distribution to leave behind an increasingly large share of the population, which (up until now) has been relatively successfully mitigated by the welfare redistributive system. Since 1994, the gap between the before- and after-welfare transfers poverty rate has increased from 14 to 27 p.p.: close to one third of the Portuguese population brought above the monetary poverty line by virtue of pensions and social transfers (Figure 9).

Figure 9 At-risk-of-poverty rates before pensions and social transfers, after pensions and after pensions and social transfers, Portugal, 1994-2021. Source: Elaborated by the author from data collected via PORDATA (2023c).

1.7. Government Provision of Basic Goods

For a given pattern of income and wealth inequality, the extent of the socialised provision of basic goods by the government makes a decisive difference to overall socioeconomic inequality. Of special relevance is government provision of the so-called four pillars of the welfare state - education, health, social security and housing (Torgersen, 1987; Kemeny, 2006) - and the universality, quality and cost of access to those publicly-provided goods and services.

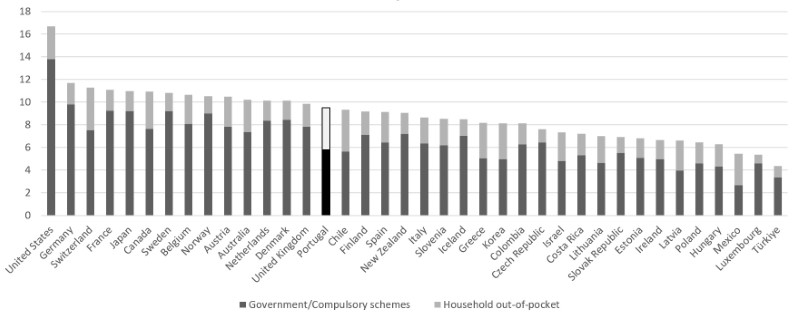

The creation of a modern, universal, and socialised welfare state in Portugal dates back to the aftermath of the 1974 Democratic Revolution, which led, inter alia, to the birth of a National Health Service (SNS) in 1979 following a Beveridge model.2 This is widely regarded as one of the great achievements of Portuguese democracy and is reflected in such remarkable developments as the reduction in the infant mortality rate from 37.9 ‰ in 1974 to 2.4 ‰ in 2021 (PORDATA, 2022a). According to Article 64 of the Portuguese Constitution (Assembleia da República, 2005), access to health care is universal, general and in principle free of user charges, although partial user fees have been introduced and withdrawn at different times throughout the history of the SNS (at present they are practically non-existent). Coverage is indeed universal and general, including the entire resident population and the various types of health care (primary, secondary and tertiary). However, some important gaps and insufficiencies have long been identified and in recent times seem to be intensifying, especially as concerns the share of the population without a reference primary health care provider and the waiting times for surgeries and specialised medical appointments. Facilitated by the rapid development of a private healthcare industry, this has led a part of the population to rely increasingly on private medical insurance schemes and out-of-pocket payments. At present, the country’s share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) dedicated to healthcare is among the highest in the OECD, but the share of voluntary/out-of-pocket contributions is currently closer to that in countries with less developed welfare systems (Figure 10).

Figure 10 Health expenditure and financing as a share of GDP: Government/compulsory schemes and voluntary/household out-of-pocket, OECD countries, 2019. Source: Elaborated by the author from data collected via OECD (2023b).

Education is another key pillar of the Portuguese welfare state, and like health, is provided universally and free of charge up to grade 12, which has been the compulsory level of education since 2009. Public and private universities coexist, but the former admit most students, with costs mostly borne by the government, although individual tuition fees for higher education continue to be charged that cover a limited part of the cost in the case of the first cycle (Bachelor’s degrees). From the second cycle (Master’s) onwards, tuition fees are substantial and government subsidising is much more limited. As with health, the Portuguese population has made tremendous progress in education in its five decades of democracy, including a reduction in its illiteracy rate from 25.7% in 1970 to 3.1% in 2021 and an increase in the share of 30-34 year-olds with a university degree from 9.8% in 1998 to 43.7% in 2021 (PORDATA, 2022b). As of 2019, an estimated 4.8% of GDP were spent on educational institutions in Portugal (across all levels: primary to tertiary), in line with the EU22 (4.5%) and OECD (5.0%) averages (OECD, 2022: 265). Of these 4.8%, 4.0 p.p. originated in public sources, 0.7 p.p. in private ones and 0.1% came from international funds (ibidem), which illustrates the residual nature of private spending in education and the nearly universal coverage of the public educational system. Indeed, most private spending in education reflects social differentiation strategies on the part of wealthier parents who opt for private schools, rather than lack of access to the public system.

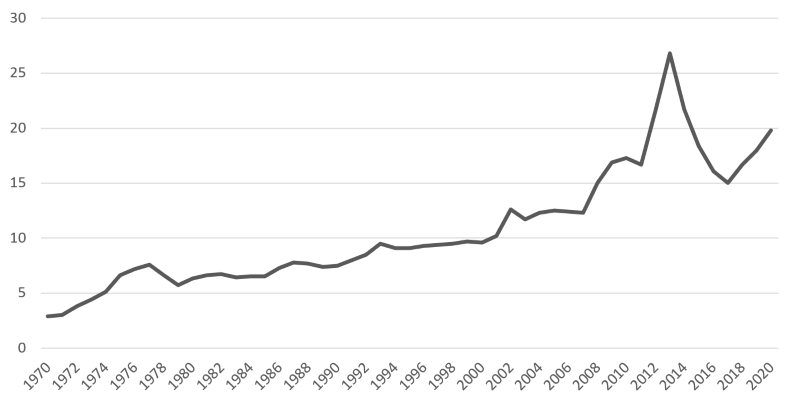

The Social Security system in its current form is also a child of the Democratic Revolution, having been established as a universal right in Article 63 of the Constitution (Assembleia da República, 2005) and dating back to its original 1976 version. A variety of social protection regimes were introduced over the following decade: contributory and non-contributory old-age pensions, unemployment benefits, disability benefits, sick and parental leaves, etc. The 1990s saw the introduction of additional welfare benefits and schemes aimed at tackling poverty and social exclusion, particularly for children, the disabled and the severely socially excluded.3 The country’s social security system today is a sophisticated structure that combines a hybrid pay-as-you-go system with partial redistributive characteristics, a variety of additional benefits introduced over time and subject to various conditions or means-tests, and direct support to the functioning of social facilities like day-care centres, nursing homes and crèches. This has led to the consistent growth of social expenditure as a share of GDP (Figure 11). Nevertheless, it is widely recognised that government support in the areas of long-term care, especially in the case of dependent elderly and disabled persons, as well as the care of very young children, is very insufficient, as a consequence of which responsibility falls to a great extent on the shoulders of family members and gives rise to serious situations of both inequality and indigence. Also, while pensions and social transfers effectively lift millions of Portuguese above the poverty line (see Figure 9), an estimated 16.4% remained at risk of poverty in 2022, which provides a measure of the inability of the system to fully address poverty and social exclusion. Additionally, several threats to the redistributive and universalistic character of the system have long been present which have intensified and in some case materialised at times of economic recession and budget tightening, including pressures to tighten the conditions of access to the various benefits and attempts to introduce limits to the mandatory contributions so as to facilitate the development of private fully funded supplementary schemes (Pereirinha and Murteira, 2020).

Figure 11 Social security expenditure as a share of GDP, Portugal, 1970-2020. Source: PORDATA (2022c).

Finally, housing is clearly the weakest link when it comes to government provision of basic goods. This is not uncommon - it has elsewhere been recognised as the “wobbly pillar under the welfare state” by Ulf Torgersen (1987) -, but public housing provision in Portugal has a very residual nature even for the standards of comparable European countries. Housing accounts for a very small share of total social expenditure, and public housing provision accounts for a very small share of total new housing provision (Santos et al., 2014). The total publicly owned housing stock amounts to a mere 2% of the total, which compares very unfavourably to most other European countries (Antunes, 2019). In this context, public housing has been targeted almost exclusively to the poorest and most socially excluded social groups, particularly in the context of slum eradication. With little affordable rental housing either provided or promoted by the government, the Portuguese population was instead pushed to the owner-occupier option, facilitated by the goverment’s subsidisation of housing credit from the 1990s onwards, which effectively became the key public housing policy strategy (Santos et al., 2014). The massive inflow of international credit in the context of the particular political-economic structures of the Eurozone in the 2000s further fuelled this tendency and was followed in the 2010s by the deliberate opening up of the real estate market to international investors by means of tax benefits for non-residents and real-estate investment funds as well as golden visa schemes. As a consequence, housing has been turned primarily into a financial asset and has undergone enormous valorisation over the last few years, especially in gentrified city centres. This has led to the exclusion of large segments of the population from the housing market and driven an additional inequality wedge between the housing haves and have-nots.

2. Portugal’s Inequality Regime: Processes and Mechanisms

The previous section summarised the main patterns of socioeconomic inequality in Portugal and its evolution in the last few decades. This section seeks to identify the processes and mechanisms which account for those patterns. The general context is that of a semiperipheral social formation that underwent a process of late industrialisation in the late 20th century but which never quite reached the levels of industrialisation, productive complexity or Fordist regulation typical of more advanced and more central capitalist economies (Santos and Reis, 2018). Instead, the modernisation and qualification process was short-circuited by its partial replacement with a finance-led regime of accumulation with semiperipheral features, characterised by capital inflows, chronic external deficits, premature deindustrialisation and a process of relatively low-skilled and low-productivity tertiarization, although with sporadic heterogeneous pockets that include more sophisticated industries (ibidem; Caldas, 2020). Especially from around the turn of the millennium, the Portuguese economy entered a long-term stagnation period that was temporarily compensated by the inflow of credit and access to relatively cheaper consumer goods, but which entered into overt crisis in the context of the Eurozone crisis and the structural adjustment programme that was subsequently implemented to promote internal devaluation (2011-2014). The following years allowed for some respite, with moderate economic growth and some recuperation of wages and social benefits following a change of government and the evolving international circumstances, but the Portuguese economy and government continue to live under the threat of a massive external and public debt overhang. It is against this background that we shall now discuss the inequality dynamics associated with the capital-labour relation, classification struggles, financialisation dynamics, redistributive mechanisms, and public provision of goods and services.

2.1. The Capital-Labour Relation

The capital-labour antinomy is the chief defining characteristic of capitalist economies as well as the principal inequality-generating mechanism in modern societies. The concentration of the ownership of productive and financial assets implies that regressive changes in the functional income distribution (in the sense of more income accruing to capital) tends to be associated with regressive changes in the personal income distribution (in the sense of greater interpersonal inequality).

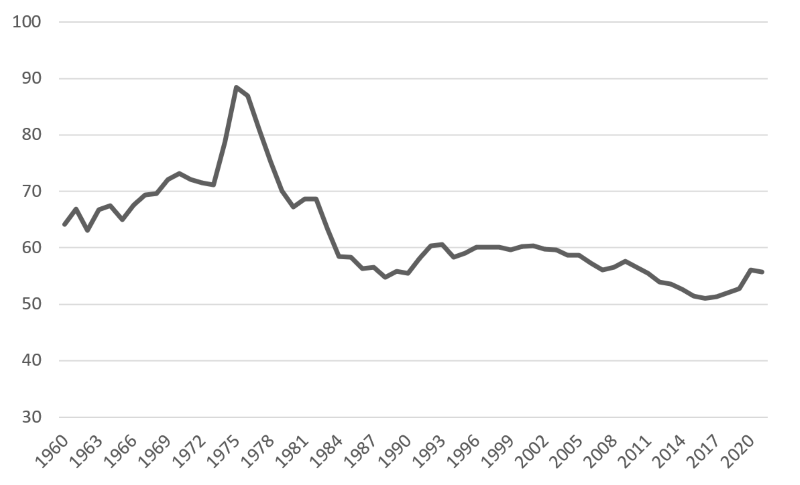

In a comparative cross-European perspective, we find that labour’s share of income in Portugal is somewhat below the European average: the adjusted wage share as a percentage of GDP at market prices in 2019 was 52.7%, compared to 55.3% in the EU as a whole4 (AMECO, 2022), which is a contributing factor to the country also exhibiting above-average interpersonal inequality. When we turn to its evolution over time, several interesting features stand out (Figure 12).

Figure 12 Adjusted wage share (% of GDP at market prices), Portugal, 1960-2020. Source: AMECO (2022).

First, it is worth noting the relatively high labour share of income (for today’s standards) even before the democratic period, which may be reflective of the country’s very incipient degree of industrialisation and capitalist accumulation at the time. The wage share then reached record levels in the mid-1970s post-revolutionary period, following the nationalisation and worker takeover of control over many businesses as well as the introduction of previously inexistent workers’ rights and benefits. This was rather short-lived, however, and was followed by 15 years of a consistently pro-capital distributive backlash, facilitated by macroeconomic dynamics, particularly inflation (Abreu, 2020), and by a variety of political and institutional processes, including two International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout agreements in 1977 and 1983, pro-market Constitutional amendments in 1982 and 1989, the build-up to and accession to the EU in 1986, and the liberalisation of the banking system in the 1980s. These various factors acted jointly to reassert the place and power of capital in Portuguese society, to bring about a drop in the adjusted wage share from 88% in 1975 to 55% in 1988, and, surely enough, to make a major contribution to the increase in interpersonal inequality in the 1980s that can be seen in Figures 3, 5, 6 and 7.

Throughout the 1990s and up until the early 2000s, however, the data show a relative stabilisation of the wage share, suggesting that other mechanisms have been at work to account for the continuing surge in inequality. Conversely, from the 2000s onwards the wage share once again experienced a downward trend, bringing it to a record low of 51% in 2016, in the wake of the Eurozone crisis and the IMF-ECB-EC5 structural adjustment programme (which severely weakened workers’ rights and collective bargaining), before recuperating slightly in the last few years. Remarkably, however, that declining trend in the wage share occurred alongside a moderate but generally consistent decrease in interpersonal inequality. This indicates that we must additionally consider other processes and mechanisms to fully account for the observed patterns.

2.2. Classification Struggles

The concept of classification struggles (“luttes de classement”), proposed originally by Pierre Bourdieu, is employed by Boyer (2015b) to refer to processes which generate inequalities among wage earners, namely due to differences in education, skills, access to stable employment contracts and other factors, thereby acting as a second major driver of socioeconomic inequality.

Combining different sources, we find that this second source of inequality complements the earlier conclusions and makes it possible to reconcile our empirical findings. Indeed, Rodrigues (2007) concludes that a large part of the inequality increase in the 1989-1995 and 2000-2005 periods was due to changes in the educational structure of the population and to the greater increase in wages in the top end of the scale. Similarly, Alvarado (2010: 576), who looks specifically at wage inequality between the 1960s and the early 2000s, finds a steady increase in the top wage shares in the 1980s and 1990s, and argues that “the increase in overall income concentration over the last years [up to the early 2000s] in Portugal has […] been extremely influenced by the evolution of top wages”. Alvarado further distinguishes between two subperiods: in the 1980s, the increase in the top wage shares was relatively more broad-based, benefiting the top 10%; then, in the 1990s, it was concentrated in the very top 1%, a pattern consistent with the data in Figures 5 and 6. These patterns may reflect different processes and mechanisms at work simultaneously: the social and economic differentiation of the holders of relatively scarce education and skills in a context of economic opening and liberalisation; but also the emergence of a group of top corporate managers fully aligned with the interests of capital but nominally classified as wage-earners, as is typical of the neoliberal period. The comparative analysis of the evolution of the incomes of the top 10% and 1% in Figures 5 and 6, suggests that the former process was likely most intensely at work in the 1990s, declining somewhat thereafter; while the latter process, which is likely to appear in the trajectory of the top 1%, persisted in the 2000s and 2010s.

At the same time, the liberalisation of the labour market and the dismantling of the existing incipient Fordist regulatory institutions, such as union participation, collective bargaining (which dropped precipitously in the 2010s) and standard employment contracts, has led to the emergence of new sources of classification inequality. Paulo Fernandes (2021) analysed the impacts of non-standard employment contracts in the Portuguese labour market based on administrative microdata while controlling for the effect of other variables, and found a consistent hourly wage premium in the vicinity of 15%-25% from about 2009 onwards for permanent full-time workers relative to workers on temporary, fixed-term and other non-standard employment contracts. Thus, the liberalisation and deregulation of the labour market, which was advanced especially forcefully in the context of the Eurozone crisis and ensuing structural adjustment programme, not to be undone by subsequent governments, constitutes a double driver of inequality: between labour and capital, on the one hand, and among workers, on the other.

2.3. Financialisation

Financialisation introduces a fundamental tension between productive and financial capital, with important consequences for the productive specialisation pattern and the growth regime. As far as inequality is concerned, financialisation is typically associated with more unequal functional and interpersonal income distributions, brought about by the growth in rentier income and by processes of financial expropriation directly from the workers and popular classes to finance.

The particular features that financialisation has taken on in the Portuguese context have been described in detail by João Rodrigues et al. (2016) and Ricardo Paes Mamede (2020), among others. The process has been closely associated with the process of integration into the Eurozone and the enormous inflows of credit from the European core that ensued, especially in the 2000s. These reinforced the distortion of the productive structure in favour of non-tradable goods, especially real estate, construction, retail trade and distribution, and finance, while rapidly increasing the indebtedness levels of families (especially housing credit), companies and the government. In turn, this contributed to income concentration at the very top (see Figure 5) through several concurrent processes: the relative ascendency of industries (especially finance, distribution) with a more concentrated capital ownership structure than typically characterised Portuguese manufacturing industry; and the increase in the direct extraction of financial profits out of household income. The national and international holders of these particular fractions of capital - typically dominating such protected sectors as retail and distribution, banking and finance, real estate, and utilities, and seldom venturing into more dynamic industrial capitalist ventures - constitute Portugal’s rentier class par excellence.

Moreover, in the Portuguese context financialisation has crucially involved the conversion of housing and real estate into a central class of financial assets, followed by their continuing valorisation driven by the inflow of domestic and international capital. This has had profoundly ambiguous effects: on the one hand, it has increased the net wealth of a majority of Portuguese households (73% of whom owned their own home by 2011, compared to 64.6% in 1991 - cf. Xerez et al., 2019: 14). On the other hand, it has led to a widespread crisis of access to housing on the part of those households that are not homeowners, as well as for young people seeking to emancipate themselves as autonomous households.

2.4. Redistributive Mechanisms

Writing in 1993, Boaventura de Sousa Santos (apud Santos and Reis, 2018) highlighted how the gaps and insufficiencies of the Portuguese welfare state were partially compensated by the intervention of a broader welfare society, composed of networks of relationships of mutual knowledge and self-help, based on family and neighbourhood ties. Three decades later, these continue to be essential in many respects, from long-term care of the dependent elderly and the disabled to providing a recourse solution to the housing crisis by enabling many young people to continue to live with their parents until rather late in life. However, it can also be said that over the past thirty years the Portuguese society has moved closer to a social-democratic model of welfare and further away from its conservative-corporatist origins, to refer to Esping-Andersen’s (1990) classic typology.

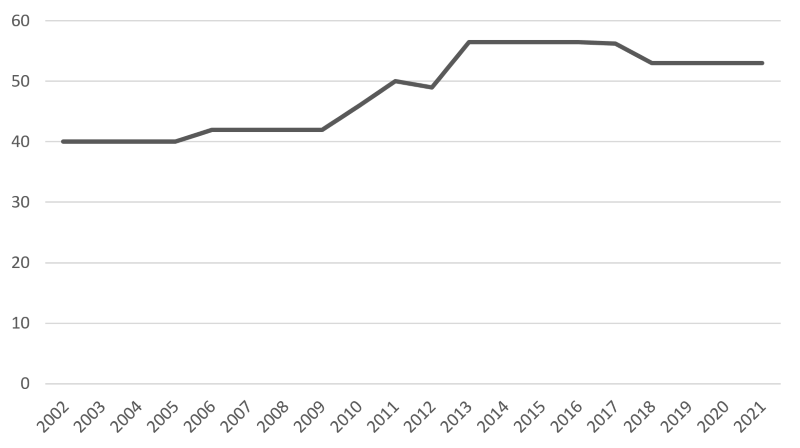

Certainly, despite the various pressures that it has been subjected to, the Portuguese welfare state has successfully mitigated socioeconomic inequality, and in some respects effectively reduced it over time. Several lines of evidence converge in support of this conclusion: the reduction in inequality indicators such as the Gini index and the S80/S20 index over the last two decades (Figure 4); the increase in the differential between the pre- and post-tax shares of national income of the top 1% and top 10% (Figures 5 and 6); the substantial long-run increase in social security expenditure as a share of GDP (Figure 11); the relative recuperation of the income shares of the bottom 10% and bottom 20% income groups in the last twenty years (Figure 7); and the impact of pensions and social transfers in lifting a substantial portion of the population out of monetary poverty (Figure 9). Against a background of rampant neoliberalism, deteriorating functional income distribution, greater classification inequalities and advancing financialisation, this is no small feat, and would not have been possible were it not for the significantly progressive characteristics of the personal income tax system (Figure 13) and a social protection system which is more comprehensive and better at redistribution than it is sometimes given credit for.

Figure 13 Top statutory personal income tax rates, Portugal, 2002-2021. Source: Elaborated by the author from data collected via OECD (2023a).

The main weaknesses in the Portuguese welfare system are also clear, however. First, the inability to mitigate wealth inequality to any meaningful extent. Taxes on property are relatively minor in the Portuguese context, not very progressive and therefore seemingly unable to prevent the accumulation of wealth inequality. In 2021, they represented a mere 3.5 billion euros out of a total of 75 billion euros in tax revenue. These property taxes apply mostly to holders and buyers of real estate: there is no general wealth tax and even the inheritance tax, which is common across Europe and used to exist in Portugal, was scrapped in 2003 (though 10% stamp duty may apply in some cases). Second, the fact that around one sixth of the population (1.6 million people), many of whom employed or self-employed, are still left below the poverty line. This is due to a combination of low wages, low work intensity in poorer households and insufficient coverage and/or amounts of the various pensions and benefits under both the contributory and social protection arms of the social security system. Third, government provision of basic goods leaves several key needs unmet, especially in the areas of housing (with public provision limited to the very poorest), care for the elderly, the dependent disabled and early childhood, and, increasingly, timely and comprehensive medical care.

The main threats pending upon it are equally clear. On the one hand, an inequality regime in which government redistribution seems to be the only barrier against rapidly increasing inequality is inherently vulnerable. In a context of labour market deregulation, decreasing unionisation and collective bargaining, increasing wage inequality, deteriorating functional income distribution and advancing financialisation, we find that the primary (market) income distribution is characterised by increasing poverty rates and inequality levels, and the ability to maintain the final outcome under check through politically-determined redistribution can be quickly eroded by virtue of changes in political and/or economic circumstances.

It is probably accurate to say that the Portuguese society and electorate has so far exhibited a high degree of aversion to inequality. However, it is equally true that the proliferation of targeted and means-tested welfare benefits, in some cases limited to the very poorest, as opposed to universalistic welfare solutions, tends to breed political disaffection and weaken the systems of public provision. Housing has always been the classical example of this, but there are fears that the same process could spread to other domains. The risk is that, under increasing ideological and budgetary pressure, the government chooses to increasingly target only the neediest in areas like health and old-age pensions, gradually replacing a universal welfare system with a poor system for the poor and allowing the more affluent classes to seek their privately-funded and privately-provided solutions.

A second major threat is the disappointing performance of the country’s growth and accumulation regime. The generally weaker and more unstable dynamism of finance-led accumulation regimes under neoliberalism is particularly fragile in a semiperipheral context like Portugal, which was hit especially hard by the competitive shocks associated with the exposure to greater international competition in the 1990s and participation in a dysfunctional monetary union. Annual GDP per capita growth at constant prices has averaged a mere 0.5% since the turn of the millennium, while the external and public deficits have soared. This gives rise to intense budgetary pressures at times of structural crises or cyclical downturns, which can force through the erosion of some of the welfare and redistributive mechanisms discussed so far in this paper. At the same time and on a more permanent basis, the fiscal discipline rules associated with participation in the EU and Eurozone also tend to limit the policy space for the preservation of the welfare state.

Third, Portugal will undergo a rapid and especially intense process of demographic ageing in the next few decades due to the longevity gains and especially the country’s ultra-low fertility in recent decades (Sobotka, 2016). This will inevitably place greater demands on the welfare system and intensify political disputes over the amount, sources and applications of social expenditure. In this respect, it is worth noting (Figure 9) that while pensions accounted for 10 p.p. of the total 16 p.p. difference between before- and after-welfare-transfer poverty rates in 1994, in 2021 pensions accounted for 21.8 p.p. out of 26.9, i.e. pensions are increasingly central to poverty eradication and could end up crowding out other forms of welfare transfers and public-good provision.

And fourth, the Portuguese welfare system faces a threat of the key domains of healthcare and social security being increasingly opened to commodified provision and private profit, justified by ideological arguments around private efficiency and insufficiency of government resources, thereby gradually dismantling the universal, redistributive and egalitarian character of these components of the welfare state and replacing them with basic safety nets for the poor alongside privately-funded and privately-provided differentiated services for the more affluent.

Conclusions

Our analysis of the empirical patterns of socioeconomic inequality in Portugal over the past few decades has identified some remarkably contradictory characteristics of this country’s inequality regime: it is among the most unequal countries in Europe, yet income inequality according to most measures has gone down in the last two decades; top incomes have been curbed in recent times, but those at the very top have remained unabated, as has wealth inequality; monetary poverty has undergone a considerable reduction over the long-term, but the share of the population below the poverty line continues to be high for European standards, and poverty rates before social transfers have in fact increased over time; free, universal healthcare provision by the government is one of the greatest successes of Portuguese democracy, but is under increasing strain; government provision of education, health and social security is consistent with a modern social-democratic welfare state, but public housing provision, the “wobbly pillar”, is especially residual.

When we discussed the underlying processes that account for these patterns and contradictions, we have argued that a largely deteriorating functional income distribution, increasing social and income differentiation among wage earners and the ascendency of finance all combined to account for rapidly escalating socioeconomic inequality in the 1980s and 1990s. These underlying processes persisted after the turn of the millennium, but in some cases with less intensity, and were effectively counterbalanced by welfare redistribution mechanisms to the extent that most measures of inequality in effect experienced a sustained reduction in the last two decades. Nevertheless, wealth inequality and the very top incomes have continued to soar, driven by financialisation and due to the relative inefficacy of the corrective mechanisms in that respect.

While it is remarkable that a semiperipheral and largely stagnant economy with an incomplete welfare system has managed to significantly curb socioeconomic inequality in a context of financialisation and neoliberalism, it is clear that this outcome has been almost entirely dependent on politically determined redistribution. As such, it is especially vulnerable to the many pressures that it is likely to continue to face going forward, including in budgetary, demographic and political-ideological terms.

Finance-led accumulation regimes tend to be less dynamic in terms of growth, more prone to crises and more unequal. Portugal’s particular turn to such a financialised regime in the last few decades has had all of these effects, even if the inequality dimension has been kept more or less in check through the action of the welfare system. However, under the pressure of low growth and ever-squeezing fiscal space, this solution can only stretch so far: it has proven increasingly difficult in recent times for Portuguese governments to simultaneously keep public debt under control, ensure adequate pensions and social transfers, and avoid the erosion of key public services. The political dilemmas that all of this involves, and which possibly can only be decisively addressed through a more fundamental overhaul of the growth regime itself, will likely remain with us for the next few years to come.