Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Tourism & Management Studies

Print version ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies no.7 Faro Dec. 2011

The Integral Rural Tourism Experience from the Tourist’s Point of View – A QualitativeAnalysis of its Nature and Meaning[i]

A experiência turística rural integral do ponto de vista do turista – uma análise qualitativa da sua natureza e significado

Elisabeth Kastenholz1; Joana Lima2

1Senior Lecturer, Coordinator of the Research Project "The overall rural tourism experience and sustainable local community development" Research Unit GOVCOPP, University of Aveiro elisabethk@ua.pt

2Lecturer, Research Assistant in the Research Project "The overall rural tourism experience and sustainable local community development" Research Unit GOVCOPP, University of Aveiro jisl@ua.pt

ABSTRACT

Rural areas have attracted increasing interest as a space for leisure and tourism, as a result of recent trends in tourism demand, especially from urban populations. However, although the literature on the tourist experience has increased significantly in the past decades, the tourist experience of visiting rural areas remains a relatively understudied field of research.

In this context, this paper aims to analyse the nature of the tourist experience in a rural context, focusing on the tourists’ point of view. Concretely, in-depth interviews were conducted with 44 individuals who had visited rural areas, aiming at a deeper understanding of the three phases of the tourist experience: (i) pre (planning, expectations and motivations); (ii) during (events occurred during the visit); and (iii) after the experience (satisfaction, memories and evaluation of the visit).

The results show that the countryside is imagined as a space opposed to the negative aspects of the urban space, ideal for resting, recovering forces and living as a family, often associated with the possibility of getting to know the "ancient" and "traditions". However, results also show that rural tourism destinations should seek alternatives to create a dynamic that attracts/ satisfies tourists without damaging their natural, cultural and social resources.

KEYWORDS: Tourist Experience, Rural Tourism, Exploratory Study, Qualitative Research.

RESUMO

As áreas rurais têm suscitado um interesse crescente como espaços de lazer e turismo, em consequência das recentes tendências da procura turística, especialmente das populações urbanas. No entanto, apesar de a literatura acerca da experiência turística ter aumentado, a experiência vivida pelos turistas quando visitam espaços rurais permanece uma área relativamente pouco estudada.

Neste contexto, o presente trabalho tem como objectivo analisar a natureza da experiência turística em meio rural, do ponto de vista dos turistas. Na prossecução deste objectivo foram aplicadas entrevistas em profundidade a 44 indivíduos que já tinham visitado espaços rurais, visando uma compreensão aprofundada das três fases de uma experiência turística: antes (i) (planeamento, expectativas e motivações para realizar a visita); (ii) duante (ocorrências e actividades durante a visita); e (iii) depois (satisfação, memórias e avaliação da visita).

Os resultados obtidos revelam que o espaço rural é imaginado como um espaço em oposição aos aspectos negativos do urbano, ideal para descansar, recuperar forças e conviver em família, muitas vezes associado à possibilidade de conhecer o "antigo", as "tradições". Porèm, è ainda revelado que este espaço, enquanto destino turístico, deve procurar alternativas para criar uma dinâmica que atraia/ satisfaça os turistas, sem descaracterizar a sua base distintiva de recursos.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Experiência Turística, Turismo Rural, Estudo Exploratório, Estudo Qualitativo.

1. INTRODUCTION

Rural tourism has deserved increasing interest from tourism researchers and practitioners in the past decades as a result of the recognition of both its potential for enhancing rural development and of market trends making rural areas stand out as spaces particularly apt to accommodate new tourism and market demands. These demands are associated with the search of the "authentic", a nostalgically embellished past, the perfect integration of Man in Nature, outdoors activities in natural contexts, scenic beauty and relaxation in a calm and peaceful environment, far away from busy cities (Cavaco, 2003; Frochot, 2005; Kastenholz, Davis & Paul, 1999; Kastenholz, 2010; Kastenholz & Sparrer, 2009; Lane, 2009; Ribeiro & Marques, 2002; Rodrigues, Kastenholz, & Morais, 2011).

Based on a variety of endogenous natural and cultural resources, of both material and immaterial quality, diverse types of experiences may be designed in rural areas, in a way to attract and satisfy a heterogeneous rural tourist market. However, the construction of these experiences represents a challenge -for the community, local service providers and tourists alike. On the one hand, the community’s identity must be understood as one of these area’s most important resources, for the development of the territory as much as for the development of significant and distinct tourism experiences that respond to the search for authenticity, the genuine and traditional, a resource that needs to be intelligently integrated in tourist experience design and simultaneously protected from over-exploitation. On the other hand, there is a need to create experiences that, while satisfying the tourist, resulting in significant, emotion-rich memories, guarantee satisfactory and sustainable economic returns for the local agents of supply.

Given the complexity of the tourist experience, especially in the case of a rural tourism destination, an integral perspective of the overall tourist experience seems to be the most appropriate form to analyse the phenomenon: an experience shared and conditioned by tourists, local community and local economic agents, in the context of a specific territory with unique and distinctive resources (Kastenholz, 2010).

In the present paper, using results from exploratory research in the context of a larger research project on the global tourism experience in rural areas, this experience is analysed from the perspective of the tourist. Larsen (2007) recommends that a detailed analysis of the experience lived by tourists should integrate at least the phase of travel planning, the phase of visiting the destination and the individual memories resulting from this experience, after the visit, which is the approach adopted here.

The paper starts with a brief conceptualization of the tourist experience, in general, to then focus on the tourist experience lived in rural areas and finally, in the second part, present results of an empirical study that help understand the meaning and the elements of the experience lived by tourists in rural areas, in the three before-mentioned phases.

2. THE RURAL TOURIST EXPERIENCE – AS LIVED BY THE TOURIST

There is an increasing consensus regarding the tourist experience as the central element of the tourist phenomenon, deserving profound analysis, especially when aiming at the development of an appealing, successful and distinctive tourism product (Ellis & Rossman, 2008; Li, 2000; Mossberg, 2007; Stamboulis & Skayannis, 2003).

Larsen (2007) defines the tourist experience as "highly complex psychological processes" (pp.8), "psychological phenomena, based in and originating from the individual tourist" (pp.16). Elands & Lengkeek (2000) refer to Cohen (1979) suggesting that "travelling for pleasure (as opposed to necessity) beyond the boundaries of one’s life-space assumes that there is some experience available "out there" (Cohen, 1979:182), which might not be found within the daily life context, an experience that gives significance to the trip and makes the tourist "forget" about his/ her "daily world", travelling to "another world" -an imagined and idealized one. This phenomenological approach considers the tourist experience as meaning something less tangible and more gratifying than just travelling to the destination – the tourist’s search for a "centre". This conceptualization of the tourist experience stresses its distinctive nature, remote from daily life, and "the <other> [encountered through travelling] as a means to connect with an imagined, ideal world" (Elands & Lengkeek, 2000: 2; Cohen,(1979). Elands & Lengkeek (2000) suggest, in this context, that the experience may assume distinct formats or modes, namely "amusement" (something fun and temporary; entertainment in a familiar context), "change" (relax and escape from daily life, monotony or stress), "interest" (search for knowledge, novelty and variety), "rapture" (enchantment/ecstasy, self-discovery, challenge, the unexpected) and "dedication" (search for the authentic, devotion, merge/ being absorbed in a "backstage" world, timelessness). As a consequence, one and the same experience at a rural destination may be lived as more or less entertaining, at ease, dedicated, transforming or recuperating, depending on the predominant experiential mode lived by the individual tourist.

In the general management, marketing and consumer behavior literature, the consumer experience has received increasing interest, with Pine & Gilmore’s (1998; 1999) seminal work sometimes referred to as the foundation of a new economic paradigm: the post-services economy, designed as "experience economy". This seems a most appropriate approach to the understanding of the tourism economy, since it is a field where "experiences have always been at the heart of the entertainment business" (Pine & Gilmore, 1998:99). Examples of this perspective in the tourism field are thematic hotels and restaurants, transporting their clients to new realities, permitting distinct, frequently co-creative experiences, based on themes as core experiential or meaning dimensions, e.g. based on a geographical location, cultural specificities, a specific time period, particular activities, amongst others.

In recent years, another analytical and managerial approach, with potential relevance for rural tourism, has appeared in the tourism literature – "intimacy theory", with its roots in the "embeddedness theory" (Granovetter, 1985; Winter, 2003) and in "relationship marketing" (Berry, 2000). In this perspective, tourism offerings are not only "memorable", but also experiences with a personal meaning, mainly due to a close relationship between the tourist and the host (Romeiß-Stracke, 1998). In this context, the mise en place is substituted by ritualization, evoking feelings of "protection" and of "cocooning", in contrast to "adventure" and "adrenaline", associated to some types of tourist experiences. This "intimist" experience would be based on a trust relationship between the tourist and the host community. For example, when a local community presents a locality/destination to the tourist, this locality is transformed into a "sacred value not easily disclosed to people not trusted" (Trauer & Ryan, 2005:482). Apart from this, the "intimist tourist" is suggested to reveal interesting consumption behaviors, as valuing quality and uniqueness over quantity, both at home and at their "second home", represented by their holiday destination: these tourists prefer acquiring gourmet products and may instead of undertaking several trips prefer really enjoying the one "dream journey" (Romeiß-Stracke & Born, 2003).

Since this "intimacy approach" is still recent in the tourism literature, a clear identification of corresponding market segments is difficult. However, given the symbolic meanings of the "rural tourism consumption" (Roberts & Hall, 2004), it seems reasonable to expect that rural tourism providers may attract and satisfy rural tourists by adopting strategies both based on "intimacy" and "experience theory". There is, in fact, evidence in the tourism literature showing the success ofappealing nature and heritage interpretation, with these interpretations evoking meanings and emotions, with sentimental and even romantic connotations being particularly attractive with the majority of those looking for living a, frequently nostalgically embellished, rural tourism experience (Kastenholz & Sparrer, 2009; Silva, 2006). The tourists look for appealing, unique and memorable experiences, influenced by expectations that are, in the case of rural tourism, much associated with the search for proximity to nature, the authentic and the difference from the urban way of life (Figueiredo, 2009; Molera & Albaladejo, 2007; Silva, 2006; Kastenholz, 2004). These experiences are influenced by the supply constellation at the destination (resources and attractions) and further conditioned by a series of uncontrollable occurrences (for example meteorological conditions, surprises). All these elements, perceived as a "set of meanings", determine the tourist’s satisfaction with the holiday, as well the memories and images associated with the visited destination and later reproduced (Chon, 1990; Lichrou, O'Malley, & Patterson, 2008). These meanings are therefore shaped by both the tourism supply system and the tourists themselves.

Additionally, the tourist experience must be understood as prolonged in time, beginning with the planning process, the search for information regarding the trip and destination to visit, which is frequently lived as a pleasant anticipation of the holidays, and after the trip extended in time through memories, souvenirs, photos, significant for both the constitution of the personal memory of the experience lived at the destination and for the sharing of this experience with friends and family (Parinello, 1993). In this context, imaginary and dreamlike representations of the experience are crucial elements of the phenomenon, since what tourists purchase at a time, physical and frequently also cultural distance, are expectations of idealized experiences (Buck, 1993).

3. THE RURAL TOURIST AS THE CORE OF THE TOURISM SYSTEM

There is evidence revealing a growth tendency regarding demand for rural tourism, associated to a variety of reasons (Kastenholz, 2002; Lane, 2009; OCDE, 1994; Ribeiro & Marques, 2002). In this context, diverse studies about travel motivations and benefits sought in rural tourism destinations have been undertaken, like a study of the rural tourist market in Portugal by Kastenholz et al (1999) and later Kastenholz (2002); another by Frochot (2005) looking at the rural tourism demand in Scotland; Molera & Albaladecho’s (2007) study in Southeast of Spain; and Park & Yoon’s (2009) study of the phenomenon in South Korea. These studies show that a dominant motivation of rural tourists is the wish to "be close to nature", both for leisure, recreational and sports activities or aiming at a genuine nature experience (Rogrigues & Kastenholz, 2010). Other strong motivations for choosing a rural tourism destination are the interest in socializing with friends and family in a different environment, the interest in exploring a region in an independent, spontaneous manner, the search for widening horizons, including a general interest in traditional culture and the "rural way of life".

As a matter of fact, several studies undertaken in the past decades suggest a generally increasing demand of "different holiday experiences", in diverse contexts and with distinct themes and activities, associated to increasing levels of education and of growing travel experience within the main tourist markets. These trends, together with growing levels of holiday splitting, increasing interest in and concern about heritage preservation, search for "the authentic", physical and spiritual wellness, a renewed environmental consciousness and interest in nature, find fertile ground in rural territories (Chambers, 2009; OCDE, 1994; Poon, 1993; Todt & Kastenholz, 2010).

Another important motivating factor is the search for more personalized, "intimist" relationships, thegenuine contact with the local community, as made possible in rural tourism accommodation units, an element that may be central to the quality evaluation of the tourist experience (Tucker, 2003). In the rural context, tourists frequently look for a special relationship with their hosts as a means of getting to know their way of life, simultaneously enjoying genuine hospitality and getting to know the authentic cultural context of the host community. One should therefore understand the hosts and the local population, in general, as a significant element in the construction of a complete rural tourism experience product (Kastenholz & Sparrer, 2009). However, this contact between tourists and residents may, according to Tucker (2003), also result in negative effects: visitors may also experiment negative sentiments of restrictions and obligation (e.g. feeling obliged to follow a specific recommendation), as a result of excessively intense social exchange, while the local community, on the other hand, may experiment a sensation of invasion of privacy. It is thus essential to design experiences that simultaneously guarantee an appropriate balance between social exchange and autonomy/privacy of both parts, a balance that might be facilitated by the commercial dimension of the relationship, which might help maintain a certain distance and independence of both parties involved (Kastenholz & Sparrer, 2009; Tucker, 2003).

The complex experience occurring in the rural destination context is consequently influenced by diverse features of the physical, human, social, cultural and natural context, of which it requires elements that frequently represent central attractions and that consequently determine the tourist’s satisfaction regarding this experience (Kastenholz, 2010). However, as much as this experience depends on the mentioned context elements, it simultaneously causes impacts on this same context that must be foreseen and controlled for, especially if a sustainable rural tourism destination development is aimed at (Kastenholz, 2004; Lane, 1994).

Based on this integrated perspective of a global tourist experience, an exploratory study was undertaken aiming at analyzing in detail the meanings, expectations, motivations, emotions, moments and occurrences lived and memorized by those who had visited rural areas for a holiday experience.

4. METHODOLOGY

The tourist experience and behaviors are individual phenomena, marked by psychological factors and processes and by social phenomena that occur in the context of an interaction between individuals and individuals and their environments. This experience should therefore be understood as a complex, integral phenomenon (Jennings & Nickerson, 2006; Kastenholz, 2010; O. Silva, 2006) and as a subjective living, only accessible through introspection – the phenomenological approach, suggested by Cohen (1979) and Elands & Lengkeek (2000). Correspondingly, qualitative methods were chosen for the collection and the analysis of the here presented data. This choice is also due to the exploratory nature of the study, whose main objective is a better understanding of the rural tourist experience, as lived by the tourist, looking for ideas, pathways of reflection and research hypotheses, so as to complement the literature review undertaken. The option of choosing qualitative methodologies also follows the recent trend in consumer behavior research in the field of tourism, as visible for example in Curtin (2010), Morgan & Xu (2009), Sims (2009), Hayllar & Griffin (2005) and Shaw & Coles (2004).

Considering that the here proposed study implies analyzing and evaluating emotions, meanings and other personal opinions and behavioral options, the semi-structured individual interview seems to be the appropriate technique to collect the data. According to Quivy & Van Campdenhoudt (1998), this type of interview is often used in social research to gather opinions and assess experiences, emotions and thoughts of the interviewee, permitting both the assessment of highly idiosyncratic phenomena and a structured approach focusing on specific themes and consequently allowing for identification of patterns and eventually comparisons between cases.

The study population is constituted by all residents in Portugal, aged between 25 and 55 years that have already participated in rural tourism. This age range was defined considering previous studies that concluded the prevalence of these age groups in the rural tourist market in Portugal (Kastenholz, 2002; Silva, 2007). Considering the qualitative and exploratory nature of this study, a snowball sampling technique was used. The snowball sampling technique is usually used in exploratory studies of a specific population focusing on topics about which there is no solid knowledge base and when experimental ease of data collection is required (Tung & Ritchie, 2011; Jackson, White & Schmierer, 1996). This sampling technique consists of contacting first one element of the target population with the desired characteristics (in this case, having participated in rural tourism), and this interviewee was requested to indicate other possible, personally known, respondents who also present the characteristics required by the study. Thus, this person recommends others and these others suggests, in turn, more people that could be interested in participating in the research, until the researcher obtains the adequate set of responses, which in the present case was determined by the principle of theoretical saturation. This principle implies adding new interviewees to the sample, until the responses added make no further significant contribution to the already identified patterns of responses (Strauss & Corbin, 2008). Data was mostly collected in the interviewees’ homes, their work places or other sites suggested by the respondents for their convenience, also aiming at providing an encouraging environment for response (Tung & Ritchie, 2011).

The guidelines for the interviews were elaborated based on a literature review, resulting in 30 questions: 10 closed-ended and 20 open-ended questions. These questions cover three major fields: (i) the socio-demographic profile of the interviewee; (ii) general questions about the meaning of "holidays", of "the rural", of "rural tourism", about the general motivations for having rural holidays;(iii) questions about one particular rural tourism experience, namely the last trip made to a rural area. This last set of questions (iii) could be further divided into three sub-sets regarding each stage of the tourist experience: before, during and after the trip.

All interviews were tape-recorded in order to permit additional, in-depth analysis of all responses, with minimal loss of information. Then, all the interviews were transcribed and subject to content analysis, involving the categorization and systematization of discourses, in an attempt to identify the main issues of each respondent’s discourse as well as to permit the identification of patterns.

Data analysis involved two sequential and interdependent moments: first, an analysis of each case individually (within-case analysis); second, the search for patterns or similarities within all cases (Eisenhardt, 1989). The first moment of the analysis implies an analysis of the transcribed discourses and the categorization of their content, which was subject to further validation by a group of researchers knowledgeable about the phenomenon -a triangulation approach (using different researchers to interpret a phenomenon) (Denzin, 1978). The discourses about the experiences and meanings were also analysed in terms of the experience’s modes suggested by Elands & Lengkeek (2000) in order to better assess the quality of the experience lived in the rural areas and reach further analytical depth. Apart from this, a comparative analysis was undertaken, firstly comparing discourses with the literature review, and then trying to identify consistencies and contradictions between observations (McCracken, 1988).

5. RESULTS

5.1. SOCIO-DEMOGRAFIC PROFILE OF THE SAMPLE

Interviews were undertaken with 44 individuals, with ages between 25 and 55 years, who had already lived a holiday experience in rural areas. The mean age is about 38 years. Within the sample 30 individuals are women, 27 are married and 11 single. In total, 26 respondents live in a household without children, with 7 respondents having 1 child and another 11 have families with 2 children. Professionally active are 81% (36), namely as employees, and 5 respondents are students. As far as level of education is concerned, the sample is composed of individuals with either a secondary school level(15) or a degree of higher education (19).

5.2. MEANING OF HOLIDAYS AND THE "RURAL"

The most mentioned word respondents use for describing the meaning they attribute to "rural" is "nature" (present in 32 responses), referring particularly to the contact with nature that is possible to experience in the rural context. The next most mentioned words are "countryside/agriculture" (present in 20 responses), "non urban" (17 responses), associated with specific meanings of "distance from the city", "pure", not agitated, stress-free, unpolluted environments (opposed to the negative charge associated to the urban space), and "peacefulness/ tranquility" (referred to by 10 respondents). This meaning is well expressed by one interviewee who affirms that "rural" stands for "a calm environment, communion with nature, far from the agitation of the city". Other single associations that deserve attention are the reference to the word "green" (by 4 respondents), linked to nature, and one particularly mentioning the "diverse sensations, such as smells, flavours and colours" as meanings of the rural, illustrating the relevance of the senses when living the rural tourist experience, despite not always being verbalized by the respondents. These themes globally reflect the significance of rural tourism permitting an "escape from everyday life", particularly from the agitated, stressful, urban life -as expressed in Elands & Lengkeek’s (2000) "change" mode, as well as the frequent association of rural tourism with "authenticity" and the possible immersion into a distinct, more calm, pure and natural world, classifiable as Elands & Lengkeek’ s( 2000) "dedication" mode.

When questioned about the meaning of tourism in rural areas, the categories most frequently referred to are actually similar to those used for qualifying the meaning of "rural", with the most mentioned words being the contact with "nature" (present in 27 responses) and with "countryside/agriculture" (present in 13 responses). However, expressions associated with "traditions" – getting to know customs, habits and traditions (mentioned in 9 responses), the concrete reference to the "village" (in 8 responses), associations with "peacefulness/ tranquility" (6 responses), and "health and wellbeing" (individuals concretely refer to "breathing pure air", "healthy environment" or "healthy lifestyle" in 5 responses) are also relevant themes, as becomes visible in one interview where rural tourism is described as "tourism in small villages, in houses with antique facades, implying contact with nature and being relaxing and revitalizing". Also in this topic the experiential modes of "change" and "dedication" as suggested by Elands & Lengkeek (2000) stand out.

The fact that the meaning of "the rural" and of "rural tourism" are nearly coinciding reveals a social representation of the rural space that is dominated by the consumption of the "rural" in the context of leisure and tourism, neglecting other functions of the rural space, similar to results obtained by Figueiredo (2009), a phenomenon also designed as the "pastoral view" of the countryside.

Asked about the general meaning of holidays, interviewees indicated that "holidays mean go to places where I may "get away" and use my time doing different things from my day-to-day life" or "recharging batteries, alleviating from stress, not being concerned about schedules, enjoying life being at ease". Correspondingly, most mentioned words stress the dominant motive of getting away from it all/relaxation, looking for a "change" experience: "rest" (28 responses) and "relaxation" (9 responses), "break from the daily routine" (10 responses) and "revitalization", recovering energies (8 responses) and "freedom" (8 responses). Also the experiential mode "amusement" is present in many discourses, reflected in the words "diversion" (11 responses), "being together as a family" (8 responses), as well as the mode "interest", with reference to the wish to increase "knowledge" of unknown places, new people and different cultures and traditions (10 responses). However, mostly motivations of "escape" and compensation stand out., reflecting the relevance of the experiential mode "change", primarily linked to push motives, whereas pull motives (those attracting visitors to the particular destination) do not appear with the same emphasis and mostly refer to a cultural motivation and interest in exploring "the new" or "different" (Dann, 1977).

5.3. THE "PRE-VISITATION" PHASE OF THE RURAL TOURIST EXPERIENCE

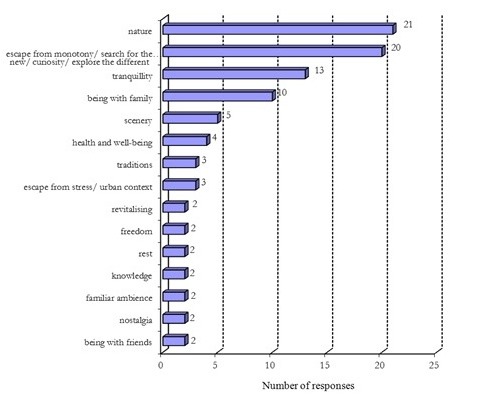

The motivations most mentioned by the interviewees are related to the appreciation of "nature" and "scenery", which are considered characteristic of the rural space, to "novelty"-"escape from monotony/ search for the new/ curiosity/ exploring the different", "peace and quiet" as the dominant ambience and at the same time a characteristic that reflects the importance of escaping from stress, confusion and noisy city-life; being with family and escape from the urban context (graph 1). Once again, the experience mode "change" stands out (escape from routine, relaxing in a calm and natural environment), followed by the modes of "interest" (novelty/curiosity), "amusement" (being with friends and family) and "dedication" (traditions, nostalgia).

Graph 1: Most mentioned categories for egaging in rural tourism

Particularly associations to the category "nature" are strong, revealing the relevance of this factor in the rural tourism experience, with individuals sometimes explicitly referring to a desired different relationship with nature, which they miss in their habitual urban living context. These results corroborate others found by diverse studies on the rural tourist market, namely by Kastenholz et al (1999, 2002); Frochot (2005); Molera & Albaladecho (2007) and Park & Yoon (2009), generally identifying nature as a prevalent motivation to visit rural areas, with Valente & Figueiredo (2003) concluding that an "uncongested space" and the "escape from the daily urban environment" are central motives for visiting rural areas.

The most often used source of information for preparing the rural holidays was the internet (29 responses), as also found by Ibery et al (2007). The second most used information source (12 responses) was word-of-mouth by friends or family who had already visited the destination before, a source that has also been identified as most important in other studies about rural tourism (Kastenholz, 2002).

As far as the planning of the holidays is concerned, 25 of the interviewees referred to a joint planning effort within the family and another 16 respondents with friends, i.e. with those participating in the trip. For reserving the accommodation, 15 interviewees used the telephone and another 10 the internet, while some did not make any reservation. Another interesting mode of planning/ reservation of the trip is associated to a new means of commercialization of rural (and other) tourism experiences in Portugal, namely "experience vouchers" ("A Vida è bela" or "Smartbox"), available in many retailing outlets and frequently acquired as gifts, being increasingly popular in the country. Even if only 2 interviewees mentioned these formats, evidence from the before mentioned on-going research project ORTE (see footnote nº 1) shows that these vouchers may play a central role for stimulating demand in some rural lodging units, eventually representing an interesting new means of disseminating the rural tourism experiences amongst a population that still largely prefers the sun and beach holidays in the Algarve (INE, 2011).

5.4. THE "ON SITE EXPERIENCE" PHASE LIVED BY THE RURAL TOURIST

The on-site experience of the rural tourist is marked by the type of accommodation used, which was mostly indicated as TER accommodation [ii] (18 responses), specifically country houses, rural hotels and manor houses, as suggested by Silva (2007). On the other hand, 6 interviewees were accommodated in the houses of friends and family. The trips were generally undertaken by groups of, in the average, 5 individuals and had a duration of about 4 nights, with the most frequently reported periods of stay being of 2 or 4 nights, as indicated by 15 and 11 interviewees, respectively. The main means of transportation used, when visiting the countryside, was the own car (40 respondents). In this context, Lew & McKercher (2006) suggest that a trade-off between cost and benefits, considering distance, is the main motivator for choosing the mode of transportation, as confirmed by the interviewees in this study who particularly stressed the benefits of the car being the most comfortable option (14), permitting greatest freedom of movement (12), being the quickest option to arrive at the destination (7), with freedom from schedules (5), but also due to the fact that it is in some circumstances the only means of transportation available to travel to certain rural destinations (5).

When asked about what had attracted most to the particular destination visited and what they liked most to get to know during the trip, the landscape stands out as the most attractive feature of the experience on-site (34 responses), followed by gastronomy (26 responses), historical heritage (11 responses), nature (8 responses), traditions (7) and peace and quite (7), as well illustrated by one statement: "everything attracted me -landscapes, gastronomy, natural and built heritage, customs and traditions". Apparently, the rural space attracts for the combination of diverse resources permitting a rich and diversified experience (Kastenholz, 2010), classifiable into the experience modes "change", "dedication" and "interest", suggested by Elands & Lengkeek (2000).

As far as activities undertaken on-site are concerned, one may conclude that these were mainly not planned, of a rather informal and spontaneous nature, with most mentioned activities being "walking/ strolling" or "touring" [iii], "hiking" and "visiting cultural/ historical sites" (museums, monuments), thereby confirming similar results of other studies on the rural tourist market (Frochot, 2005; Kastenholz, 2002).

Interviewees further referred that, despite being brief, the contact with the local population, mainly with local service providers, made these tourists feel most welcome (13), as mentioned by one particularly enthusiastic interviewee: "I loved it [the contact with local residents! They were most sympathetic in all confirms what Kastenholz & Sparrer (2009) found in their studies regarding the relevance of the local population in the construction of a richer and more complete rural tourism experience, probably contributing to a more "authentic living" of the experience of "the rural", sought particularly by those tourists motivated by the "authentic", also designed as "rural romantics" by Kastenholz (2000), and driven by the experience mode called "dedication" by Elends & Lengkeek (2000).

Purchases undertaken basically refer to souvenirs, namely the acquisition of typical products, mainly food and gastronomy products (27), specifically liquors and wine (9), but also handicraft (8) was mentioned by some. This confirms Silva’s (2007) conclusion he took from an ethnographic study of rural tourism in Portugal: "traditional food, handicraft (...) assume an outstanding position in the consumption pattern" of rural tourists. Also this behaviour reflects the importance of the experience mode designed as "dedication", making the rural tourism experience lived as more "authentic" and remembered as more meaningful.

5.5. THE "POST-VISITATION" PHASE OF THE RURAL TOURIST EXPERIENCE

Memories indeed prolong the tourist’s experience over time and increase its significance, potentially impacting on destination image through their sharing with others (Morgan & Xu, 2009; Lichrou, O'Malley, & Patterson, 2008). For 14 interviewees the destination matched their expectations, in other words the image they held of the destination was confirmed by what they actually encountered in the rural space, which is generally assumed as a baseline of satisfaction (Chon, 1990). It is worth of notice that 15 respondents were positively surprised with the landscape and nature, as stated by one visitor in the following terms: "I was indeed happy and surprised. I was surprised by the magnificent places and landscapes that exist in these rural areas". Forty interviewees stated they had not been negatively surprised with anything at the destination, but two indicated bad weather as a negative surprise marking the trip. The most positive memories associated to the rural destinations visited are landscape (22), nature (20), hospitality of the population (10), peace and quiet (8) and gastronomy (6), as highlighted by one interviewee: "the care of the local people, the flavors and fascinating landscapes are all clearly positive memories". In brief, most memories stress the qualities of the experience that had most motivated the visit to the rural areas, namely the possibility of transitorily changing the rhythm of daily life, in a rural, natural, calm and esthetically appealing and socially welcoming context. Given that local gastronomy tends to be generally appreciated by rural tourists, as already referred to, one may expect that local food products and gastronomy are amongst the most vivid, sensorial memories of the trip. As far as negative memories are concerned, 30 interviewees stated not to have any, while four mentioned the accessibility to the destinations visited. Consequently, satisfaction levels with the rural destinations are very high, with an average value of 4.3 (in a scale from 1 to 5) and 17 respondents attributing the maximum punctuation of 5. This high satisfaction level reflects in a relatively high probability to return to the destination (with a mean value of 4 in a 5 points scale) and an even higher probability to return (mean value of 4.4 in a 5 points scale). Again, these memories relate to the prevalent experience modes"change", "dedication" and "interest".

However, most interviewees (29) stated they would not like to live in the visited area, which suggests an experience mode, which is clearly transitory and might be classified, according to Elands & Lengkeek (2000) as the "amusement mode". The main reason for not wishing a life in the countryside is the fact that in the rural context the daily life is perceived as monotonous, while respondents, in fact, appreciate the city for their daily lives, not being interested in changing to the rural, relatively isolated areas, far away from the opportunities offered by the city. The countryside is, correspondingly, mostly viewed as attractive mainly for holiday periods, as a break from routine, but not as an alternative living context. However, 12 interviewees state they would like to live in the visited destination, pointing at the following reasons for such a wish: these areas’ peace and quiet (5), their landscape (4), nature (2) and quality of life (2).

6. CONCLUSION

The rural tourism experience should be understood as a complex, multi-faceted phenomenon, integrating a diversity of elements, with sensorial, affective, cognitive, behavioral and social dimensions marking the experience, along the phases "before", "during" and "after the trip" to the rural destinations. The experiences in the countryside portrayed by respondents are globally positive, with landscape and nature elements standing out in this rather "esthetic consumption experience", which might also be classified as "passive immersion", as suggested by Pine & Gilmore (1999). Most of the rural tourists interviewed additionally value signs of an "authentic way of life", traditions, and the hospitality felt in the context of personal interaction with hosts and the local population, aspects that may fall into the experience mode "dedication", as suggested by Elands & Lengkeek (2000). However, the typically urban visitor appreciates the countryside for its leisure and tourism function, for "esthetic consumption", as also evidenced by Figueiredo (2003), not showing any interest in living in rural areas, but rather visiting them in a perspective of "amusement" and "change", according Elands & Lengkeek’s (2000) typology, mainly aiming at "recharging batteries".

The market trends reveal, indeed, a potential increase of the demand of rural areas as leisure and tourism spaces, as a result of a variety of existing endogenous resources and their potential combination in tourist products, appealing to a segment that, as confirmed by our results, look for "contact with nature", wish to "get to know new places, cultures and traditions", and the "authentic/ genuine" contact with local people – central aspects of a rural experience sought and lived that may be classifiable, according to Elands & Lengkeek (2000) as the experience modes "change", "interest" and "dedication".

However, the question how to proceed, how to plan and manage successful rural tourism products that, apart from satisfying tourists, contribute to the sustainable development of tourist destinations, is a crucial issue that rural areas need to face when choosing tourism as a development tool (Kastenholz, 2004; Lane, 2009). The issues of sustainable destination development and diversification of the tourism product offered, based on appealing combinations of endogenous resources, assume an important role in this development strategy for rural areas, when considering the here presented results about the rural tourists’ main motivations when visiting the countryside. These results, corroborating those from other studies, reveal a strong push motive for visiting rural areas, like the search for experiences associated with relaxation and compensation for the agitated, unhealthy and somehow alienated life in the city (experience mode "change"), whereas pull factors, like the "search for novelty" and discovery (experience modes "interest" and particularly "rapture") are less present in the interviewees’ discourse. The respondents reveal that they mainly seek (and find) escape from their daily routines and compensation for their busy lives in the cities, when contacting with nature and the peace and quite of the rural areas. However, those responsible for managing rural destinations may also identify an opportunity for additionally exploring pull motivations by developing products/ activities that lead to a better use of the destination’s endogenous resources, through their integration in complex, appealing and distinctive rural tourism products. In this context, it is important to develop a "co-creative experience design", as suggested by Mossberg (2007), in which both destination resources and stakeholders (from diverse economic sectors) are integrated (Kastenholz, 2010; Lane, 2009), as well as, and above all, the tourist him/herself who lives this experience in its diverse dimensions -the cognitive, affective, sensorial, physical and relational (Schmitt, 1999) and for whom the rural experience may thereby become more meaningful and valuable (Ellis & Rossman, 2008).

This development of new products may not only contribute to an increased satisfaction level of actual tourists with the overall experience, but also to the attraction of new tourists, searching for different kinds of experiences (for example more challenging ones, as expressed in the experiential mode "rapture"), thereby potentially contributing to the destination’s sustainability through diversification of the tourism supply and corresponding diversification of tourism demand. When developing this complex overall rural tourism experience, meeting the needs of recent market trends, the potential and fragilities of natural and cultural resources, as well as the local community and its economic and social living context, must be simultaneously considered as constraining conditions and opportunities for the creation of appealing and distinctive rural tourism products (Kastenholz, 2010; Lane, 2009).

REFERENCES

BERRY, L.L. (2000), "Cultivating service brand equity", Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28 (1), 128-137. [ Links ]

BUCK, E. (1993), Paradise Remade, The Politics of Culture and History in Hawai, Temple University Press, Philadelphia. [ Links ]

CAVACO, C. (2003), "Permanências e mudanças nas práticas e nos espaços turísticos", in Simões, O., and Cristóvão, A., (Eds.) TERN Turismo em Espaços Rurais e Naturais, Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra, Coimbra, 25-38. [ Links ]

CHAMBERS, E. (2009), "From authenticity to significance: Tourism on the frontier of culture and place", Futures, 41 (6), 353-359. [ Links ]

CHON, K.-S. (1990), "Consumer Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction as related to destination image perception", Tese de Doutoramento, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. [ Links ]

COHEN, E. (1979), "A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences", Sociology, 13 (2), 179-201. [ Links ]

CURTIN, S. (2010), "Managing the wildlife tourism experience: The importance of tour leaders", International Journal of Tourism Research, 12 (3), 219-236. [ Links ]

DANN, G. M. S. (1977), "Anomie, ego-enhancement and tourism", Annals of Tourism Research, 4 (4), 184-194. [ Links ]

DENZIN, N. K. (1978), The Research Act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods, 3ª ed., McGraw-Hill, New York. [ Links ]

EISENHARDT, K. (1989), "Building Theories from Case Study Research", The Academy of Management Review, 14 (4), 532-550. [ Links ]

ELANDS, B. H. M., & LENGKEEK, J. (2000), "Typical Tourists: Research into the theoretical and methodological foundations of a typology of tourism and recreation experiences", Mansholt Studies, Vol. 21, Wageningen University. [ Links ]

ELLIS, G. D., & ROSSMAN, J. R. (2008), "Creating Value for Participants through Experience Staging: Parks, Recreation and Tourism in the Experience Industry", Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 26 (4), 1-20. [ Links ]

FIGUEIREDO, E. (2009), "One rural, two visions -environmental issues and images on rural areas in Portugal", Journal of European Countryside, 1 (1), 9-21. [ Links ]

FROCHOT, I. (2005), "A benefit segmentation of tourists in rural areas: a Scottish perspective", Tourism Management, 26 (3), 335-346. [ Links ]

GRANOVETTER, M. (1985), "Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness", The American Journal of Sociology, 91 (3), 481-510. [ Links ]

HAYLLAR, B., & GRIFFIN, T. (2005), "The precinct experience: a phenomenological approach", Tourism Management, 26 (4), 517-528. [ Links ]

ILBERY, B., SAXENA, G., & KNEAFSEY, M. (2007), "Exploring Tourists and Gatekeepers' Attitudes Towards Integrated Rural Tourism in the England-Wales Border Region", Tourism Geographies: An International Journal of Tourism Space, Place and Environment, 9 (4), 441 -468. [ Links ]

INE – Instituto Nacional de Estatística (2011), Estatísticas do Turismo 2010, INE, Lisboa. [ Links ]

JACKSON, M. S., WHITE, G. N., & SCHMIERER, C. L. (1996), "Tourism experiences within an attributional framework", Annals of Tourism Research, 23 (4), 798-810. [ Links ]

JENNINGS, G., & NICKERSON, N. P. (Eds.) (2006), Quality tourism experiences, Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford. [ Links ]

KASTENHOLZ, E., (2000), "The market for rural tourism in North and Central Portugal: a benefit-segmentation approach", in Hall & Richards (eds.), Tourism and Sustainable Community Development, Routledge, London and New York, 268-285. [ Links ]

KASTENHOLZ, E. (2010), "Experiência Global em Turismo Rural e Desenvolvimento Sustentável das Comunidades Locais", in Actas do IV Congresso de Estudos Rurais, Aveiro. [ Links ]

KASTENHOLZ, E., & SPARRER, M. (2009), "Rural Dimensions of the Commercial Home", in Lynch, P., MacIntosh, A., & Tucker, H., (Eds.) The Commercial Home: International Multidisciplinary Perspectives, Routledge, 138-149. [ Links ]

KASTENHOLZ, E. (2004), "'Management of Demand' as a Tool in Sustainable Tourist Destination Development", Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 12 (5), 388 -408. [ Links ]

KASTENHOLZ, E. (2002), "The Role and Marketing Implications of Destination Images on Tourist Behaviour: The Case of Northern Portugal", Tese de Doutoramento, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro. [ Links ]

KASTENHOLZ, E., DAVIS, D., & PAUL, G. (1999): "Segmenting tourism in rural areas: the case of north and central Portugal", in: Journal of Travel Research, 37, pp.353 -363. [ Links ]

LANE, B. (1994), "Sustainable rural tourism strategies: A tool for development and conservation", Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2 (1), 102-111. [ Links ]

LANE, B. (2009), "Rural Tourism: An Overview", in Jamal, T., & Robinson, M., (Eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Tourism Studies, Sage Publications, London. [ Links ]

LARSEN, S. (2007), "Aspects of a Psychology of the Tourist Experience", "Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism", 7, (1), pp.7-18. [ Links ]

LEW, A., & MCKERCHER, B. (2006): "Modeling Tourist Movements: A Local Destination Analysis", Annals of Tourism Research, 33 (2), 403-423. [ Links ]

LI, Y. (2000), "Geographical consciousness and tourism experience", Annals of Tourism Research, 27 (4), 863-883. [ Links ]

LICHROU, M., O'MALLEY, L., & PATTERSON, M. (2008), "Place-product or place narrative(s)? Perspectives in the Marketing of Tourism Destinations", Journal of Strategic Marketing, 16 (1), 27-39. [ Links ]

MCCRACKEN, G. (1988), The Long Interview, Sage, California. [ Links ]

MOLERA, L., & ALBALADEJO, I. P. (2007), "Profiling segments of tourists in rural areas of South-Eastern Spain", Tourism Management, 28 (3), 757-767. [ Links ]

MORGAN, M., & XU, F. (2009), "Student Travel Experiences: Memories and Dreams", Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18 (2), 216 -236. [ Links ]

MOSSBERG, L. (2007), "A Marketing Approach to the Tourist Experience", Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7 (1), 59 -74. [ Links ]

OCDE. (1994), Tourism Strategies and Rural Development, OCDE/GD, Paris. [ Links ]

PARK, D.-B., & YOON, Y.-S. (2009), "Segmentation by motivation in rural tourism: A Korean case study", Tourism Management, 30 (1), 99-108. [ Links ]

PARRINELLO, G. L. (1993), "Motivation and anticipation in post-industrial tourism", Annals of Tourism Research, 20 (2), 233-249. [ Links ]

PINE, J. B., & GILMORE, J. H. (1998): "Welcome to the experience economy", Harvard Business Review, 76, (4), pp.97-105. [ Links ]

PINE, J. B., & GILMORE, J. H. (1999): Experience economy: Work is theatre and every business a stage, Harvard Business School Press, Boston. [ Links ]

POON, A. (1993), Tourism, Technology and competitive Strategies, C.A.B. International, UK. [ Links ]

QUIVY, R., & VAN CAMPDNHOUDT, L. (1998), Manual de investigação em Ciências Sociais, Gradiva, Lisboa. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, M., & MARQUES, C. (2002), "Rural tourism and the development of less favoured areas -between rhetoric and practice", International Journal of Tourism Research, 4 (3), 211-220. [ Links ]

ROBERTS, L., & HALL, D. (2004), "Consuming the countryside: Marketing for 'rural tourism'", Journal of Vacation Marketing, 10 (3), 253-263. [ Links ]

ROGRIGUES, Á., & KASTENHOLZ, E & MORAIS, D. (2011), "O Papel da Nostalgia para o Turista Norte- Americano no Espaço Rural Europeu", in Figueiredo, E., Kastenholz, E., Eusébio, M. C., Gomes, M. C., Carneiro, M. J., Batista, P., & Valente, S., (Coords.), O Rural Plural -Olhar o Presente, Imaginar o Futuro, 100Luz Editora, Castro Verde, 231-244. [ Links ]

ROGRIGUES, Á., & KASTENHOLZ, E. (2010), "Sentir a Natureza -passeios pedestres como elementos centrais de uma experiência turística", Revista de Turismo & Desenvolvimento, 2 (13/14), 719-728. [ Links ]

ROMEISS-STRACKE, F. (1998), "Vorwärts: Zurück zur Natur? Trends im Tourismus und ihre Konsequenzen für den Urlaub auf dem Lande", in Burger, H-G., G. D., & Packeiser, M., (Eds.) Der deutsche Landtourismus -Wege zu neuen Gästen, DLG (Deutsche Landwirtschafts-Gesellschaft), Frankfurt.

ROMEISS-STRACKE, F., & BORN, K. (2003), "Abschied von der Spassgesellschaft", Freizeit und Tourismus im 21, Jahrhundert, Büro Wilhelm, Kommunikation und Gestaltung, Amberg. [ Links ]

SCHMITT, B. (1999), "Experiential Marketing", Journal of Marketing Management, 15 (1-3), 53-67. [ Links ]

SHAW, G., & COLES, T. (2004), "Disability, holiday making and the tourism industry in the UK: a preliminary survey", Tourism Management, 25 (3), 397-403. [ Links ]

SILVA, L. (2007), "A procura do turismo em espaço rural", Etnográfica, 11 (1), 141-163. [ Links ]

SILVA, O. (2006), "Facilitadores e Inibidores da Decisão de Participação em Viagens de Lazer -O Caso do Sotavento Algarvio", Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro. [ Links ]

SIMS, R. (2009), "Food, place and authenticity: local food and the sustainable tourism experience", Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17 (3), 321-336. [ Links ]

STAMBOULIS, Y., & SKAYANNIS, P. (2003), "Innovation strategies and technology for experience-based tourism", Tourism Management, 24, 35-43. [ Links ]

STRAUSS, A., & CORBIN, J. (2008), Pesquisa Qualitativa: Técnicas e Procedimentos para o Desenvolvimento de TeoriaFundamentada, 2ª ed., Artmed, São Paulo. [ Links ]

TODT, A., & KASTENHOLZ, E. (2010), "Tourists as a driving force for sustainable rural development -a research framework", in Actas do IV Congresso de Estudos Rurais, Aveiro. [ Links ]

TRAUER, B., & RYAN, C. (2005), "Destination image, romance and place experience--an application of intimacy theory in tourism", Tourism Management, 26 (4), 481-491. [ Links ]

TUCKER, H. (2003), "The Host-Guest relationship and its implications in Rural Tourism", in Roberts, D. L., & Mitchell, M., (Eds.) New Directions in Rural Tourism, Ashgate, Aldershot, 80-89. [ Links ]

TUNG, V. W. S., & RITCHIE, J. R. B. (2011), "Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences", Annals of Tourism Research, 38 (4), 1367-1386. [ Links ]

VALENTE, S., & FIGUEIREDO, E. (2003), "O turismo que existe não é aquele que se quer...", in Simões, O., & Cristóvão, A., (Eds.) Turismo em Espaços Rurais e Naturais, Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra, Coimbra, 95-106. [ Links ]

WINTER, M. (2003), "Embeddedness, the new food economy and defensive localism", Journal of rural studies, 19 (1), 23-32. [ Links ]

Submitted: 19.10.2011

Accepted: 25.11.2011

NOTES

[i] Initial note: This paper has been elaborated in the context of a 3 years research project designed "The overall rural tourism experience and sustainable local community development" (PTDC/CS-GEO/104894/2008), financed by Portuguese Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (co-financed by COMPETE, QREN e FEDER) and coordinated by Elisabeth Kastenholz/ University of Aveiro. See also http://cms.ua.pt/orte.

[ii] Rural Tourism in Portugal includes the following modalities: Country houses (Casas de Campo): typical rustic houses (maximum of 15 rooms) situated in villages and rural areas, which are integrated in the local architecture by their building materials and other characteristics. Village Tourism (Turismo de Aldeia): when several country houses are located in a village and are managed by only one entity. Agroturismo (AT): accommodation in rural family or manor houses integrated in a functioning farm, permitting guests to participate in agriculture. Rural Hotels: accommodation in building situated rural areas, which are integrated in the local architecture by their building materials and other characteristics. Until 2008, there was another modality of Rural Tourism in Portugal -Turismo de Habitação (TH): familiar accommodation in manor houses or palaces (maximum of 15 rooms) with high quality architecture, equipment and furniture.

[iii] The most mentioned Portuguese word "Passeios" may refer to walking around or touring around by car places, in the regional restaurants, in the cafés, and they had this very characteristic dialect of the area". This result