Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies no.7 Faro dez. 2011

Business-community partnerships: The link with sustainable local tourism development in Tanzania?

Parcerias negócios-comunidade: o link com o desenvolvimento do turismo local sustentável na Tanzânia?

Diederik de Boer1; Meine Pieter van Dijk2 and Laura Tarimo3

1Head of the Sustainable Development Centre and Director of Round Table Africa, Maastricht School of Management, The Nederlands deboer@msm.nl

2 Professor at Maastricht school of Management, Maastricht, the Netherlands

3Researcher, Round Table Africa, Maastricht, The Nederlands

Abstract

This paper investigates whether Business-Community Partnerships (BCP) can facilitate local private sector development in Africa. This study offers a new approach to such partnerships by looking at them from a local private sector development perspective using value chain analysis. Focusing on Tanzania, this paper analyses nine tourism business-community partnership cases including three NGO-initiated partnerships, three business-initiated partnerships and three cases in which there was no explicit partnership between the business and the community. Five effects of tourism development are assessed by such partnerships, namely access to capital, access to skills/ knowledge, access to markets, access to infrastructure and access to land. Overall, business initiated Business–Community Partnerships contributed positively to access of markets and access to infrastructure. The NGO-initiated partnerships contribute positively to the access of land and improved in certain cases the access to infrastructure and markets. However, appropriate transfer of entrepreneurship knowledge and access to capital remains very inadequate. This study offers a new approach by looking at partnerships from a local private

KEYWORDS:: value chains, business community partnerships, tourism, Africa, Tanzania.

Resumo

Este artigo investiga se as Business-Community Partnerships (parcerias de negócio com a comunidade) podem facilitar o desenvolvimento do sector privado local em África. Este estudo oferece uma nova abordagem de tais parcerias, encarando-as sob a perspectiva de desenvolvimento do sector privado local, utilizando a análise da cadeia de valor. Focando-se na Tanzânia, este artigo analisa nove casos de parcerias de negócio com a comunidade, incluindo três parcerias de iniciativa de ONGs, três parcerias iniciadas em negócios e três casos em que não havia parceria explícita entre o negócio e a comunidade. Cinco efeitos do desenvolvimento do turismo são avaliados por essas parcerias, nomeadamente o acesso ao capital, às habilidades / conhecimentos, acesso a mercados, acesso a infra-estrutura e acesso a terra. Globalmente, o negócio iniciado com base em parcerias de negócio com a comunidade contribuiu positivamente para o acesso a mercados e a infraestruturas. As parcerias de iniciativa de ONGs contribuem positivamente para o acesso a terra e melhoraram em certos casos, o acesso a infra-estrutura e mercados. No entanto, a transferência adequada de conhecimentos de empreendedorismo e o acesso ao capital continuam muito insuficientes. Este estudo oferece uma nova abordagem ao olhar para as parcerias sob uma perspectiva de desenvolvimento do sector privado local, usando a análise da cadeia de valor.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE:: cadeias de valor, parcerias de negócio com a comunidade, turismo, África, Tanzânia.

Introduction

Governments in African countries are struggling how to advance sustainable local private sector development. How can communities benefit more from community resources as well as from investments by outsiders? What can the government do to promote linkages between business and communities, and how can communities themselves contribute in order to benefit more from locally available resources?

Partnerships are increasingly promoted as vehicles for addressing development challenges also at the local level. It is assumed that partnerships contribute to economic development when they are working within a framework that initiates and contributes to broader processes (Pfisterer et al., 2009). However, partnership-evaluation studies have provided contradictory results. Some studies concerned positive examples (Fiszbein and Lowden, 1999), while other studies are more critical about the effectiveness of partnerships (Visseren-Hamakers et al., 2007). How partnerships contribute to private sector development at the local level needs to be better understood.

Achieving Sustainable Local Development (SLD) is the focus of this research. Local economic development is defined as „a process in which partnerships between local governments, community and civic groups and the private sector are established to manage existing resources to create jobs and stimulate the economy of a well defined area‟ (Helmsing, 2003). Local private sector development in this study refers to the upgrading of local businesses at the community level, to allow them to become better integrated in the relevant global value chains.

The analysis concerns business-community partnerships, whose economic basis is nature-based tourism activities. „Business‟ in this study refers to a private sector company or an investor. The term „community‟ will refer to the village members who are formally represented by their Village Council, owning the land where a tourism activity takes place. Nature-based tourism incorporates natural attractions including scenery, topography, waterways, vegetation, wildlife and cultural heritage; and activities like hunting (Ceballos-Lascuráin, 1996).

The challenge is to increase local private sector development without jeopardising the tourism business itself. In Tanzania, communities and businesses are experimenting with various sorts of partnerships, often involving district governments as well as the national government and NGOs. What are the pros and cons of these different partnership formulas in relation to local private sector development?

Nature based tourism in Tanzania has been chosen as the sector to study partnerships. Tourism is a fast growing industry worldwide and an important sector in Tanzania, contributing to 17.5% of its GDP[i]. However, the gap between the international tourism companies and lodges and the local communities in Tanzania is big in terms of resources and knowledge available. Without examining models to bridge this gap local communities and the local economy will not benefit from this growing industry and conflicts might occur. How can international business ventures cater for a high end market and at the same time create a more "inclusive" environment for private sector development at the local level?

This study draws on nine selected case studies which all focus on achieving sustainable local private sector development. There are three possible partnership models in the Tanzania context in which the third model is not a local partnership (and in this study the "without partnership case") but which has a local impact:

- Business - Local Government

- NGO- Business - Government (local and national)

- National Government - Business

Tourism Development in Tanzania

Tanzania is a good place to study tourism conservation partnerships as it is one of the countries in Africa where tourism, conservation and local development as objectives are being put together in partnership through the framework of recently established Wildlife Management Areas (WMA‟s). The cases were selected in order to explore the diversity of the partnership formulas and the stakeholders who engage in them but also to explore the different types of reciprocal benefits that parties hope to gain from such a partnership and the obstacles to their achievement.

Tourism is an important sector in countries which are rich in natural resources, but are economically not very developed. In 2008 Tanzania received 770,376 tourists what amounts to US $1,288.7 million of earnings (Ministry of Natural Resources, Tanzania Tourism Sector Survey, 2010). Tourism accounts for about 17.5% of its GDP, and of 25% to the country‟s foreign exchange earnings. However, the impact of tourism on improving rural livelihoods is not really analysed, because the link between tourism and the improvement of rural livelihoods is complex. Research in this area is lagging behind (Jafari, 2001; Rogerson, 2006; Hall, 2007; Simpson, 2008). Recently some districts and villages in Tanzania have benefited from tourism by developing collaborative arrangements with tour companies. Tourism companies choose to locate their lodges outside official National Parks in Game Controlled Areas (GCAs), Protected Areas (PAs) or Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs), which also have communities living in them. These locations are usually cheaper for both the tourists and the tour company. Tourists can enjoy exclusive game viewing, far from the congestion that is to be found in the National Parks. Moreover, tourists have an opportunity to experience the culture of the communities living there.

Villages allow tour companies to use an area of communal land for tourism activities and receive economic and social benefits for the village members. In turn, villagers have the responsibility of looking after the environment and wildlife but have to limit activities such as cultivation, livestock grazing, tree cutting and illegal hunting within the wildlife areas located in their village land.. In exchange, communities receive compensation from the tour companies, ranging from USD 10,000 to 80,000 per year, which is often used for building schools, clinics, and providing other facilities and social services in the village (Nelson, 2008). These kinds of agreements are currently widely practiced in areas such as Ngorongoro, Longido, Simanjiro, Babati, Mbulu, and Karatu Districts in Northern Tanzania. These activities provide a new source of communal income and employment and create a limited market for local goods. Seven villages in Loliondo Division have earned for example over US$100,000 in 2002 from several ecotourism joint ventures carried out on their lands. These figures show the potential for such arrangements between villages and tourism businesses to contribute to the economic development of resident communities in these areas

However, not all relations between investors and communities have been positive. In the same Loliondo Division, a conflict arose in 2009 between a tourism investor and the community when the resident Maasai pastoralists were evicted from their land to use it as a game hunting concession for a foreign tourism investor. The investor restricted the Maasai‟s access to grazing areas for their cattle, resulting in tension and conflicts. Some of the community members‟ homesteads and food reserves were set on fire by Tanzania‟s riot police force, leading to significant economic losses (Daily News, Sept 10, 2009). In this case, hunting activities led the villagers to face significant costs, as the economic activities on which they depend for their livelihood were negatively affected.

Barriers preventing rural communities from being included in tourism value chains

Major tourism enterprises in the private sector in developing countries tend to be owned by established businesses operating from urban centers, with many having a significant foreign ownership (Rylance, 2008; Massyn, 2008). The question is what obstacles do rural communities face to link up with international value chains? Value chain analysis will be used to understand the nature of ties between local firms and global markets, and to analyze links in global trade and production. It provides insights into the different way producers – firms, regions or countries -are connected to global markets, and how they benefit from these markets. Value chain analysis can show the distribution of benefits, particularly income, to actors participating in the global economy. It also allows identification of policies, which can be implemented to enable producers to increase their share of the benefits of globalization (Kaplinsky & Morris, 2002). Policy makers can also decide which actions to take to upgrade links in the value chain or the whole value chain to generate better returns. An important example of a policy, which has been formulated as a result of value chain analysis, is backward integration. Its aim is to increase the level of value added in the producing country, for example by processing commodities in the country of origin rather than just selling them as inputs.

Several factors have been identified in the literature why rural communities in Africa fail to actively take part in the tourism industry. A crucial factor appears to be the lack of access to capital for investment. Costs of borrowing from banks are very high in Tanzania. A lack of access to capital also prevents entrepreneurs in rural communities from benefiting from economies of scale (Ashley and Haysom, 2008), as they are not able to supply tourism products in large enough quantities to make the activity economically viable. In this research, access to capital is defined in the most literally meaning of capital, either through bank-loans or through cash payments. As communities are often involved in barter trade, any capital entering the community is seen as a required missing link in becoming part of the tourism value chain.

Rural community members also often tend to lack access to skills that allow them to participate effectively and successfully in the tourism industry. Rylance, (2008) argues that government should play a greater role in the training of local community members so that they can access the tourist market. Responsibility to promote the potential of the community-based tourism market in Mozambique, for instance, has mostly been left to foreign organizations such as the Netherlands Development Organization (SNV), and a German organization, Technoserve. Skills required by rural community members range from basic entrepreneurial skills to foreign language skills, as language has also been identified as a constraint to local economies accessing the tourism marketplace (Mbaiwa, 2008; Rylance, 2008).

Another problem is a lack of access to the tourism market networks (Ashley & Haysom, 2008). Means of global information sharing in rural areas are often limited, and villagers have no clear picture of the status of demand for tourism activities, or other products in their area. They also often lack means of reaching this market to promote products from their locality.

Access to poor infrastructure is another obstacle. Poor roads have been identified as a persistent barrier to development for local economies that exist outside of major cities (Rylance, 2008). Poor road systems means that rural communities are restricted by the lack of mobility of tourists and also the lack of transfer of knowledge and skills between communities (Rylance, 2008). Mobility of tourists is also limited because tourists tend to rely on transportation provided by the tour-operator which brings them to a specific accommodation or safari location. There is usually little opportunity for the tourists to explore local communities on their own. This makes it difficult for communities to establish economic linkages with the global tourism chain, even when they are located in the vicinity of a popular tourism destination.

The issue of access to land rights is also important as many individual residents, and even entire villages in rural areas still do not possess title documents to prove ownership of their land/property (Rylance, 2008). This prevents individual entrepreneurs and communities from having security in the use and lease of this resource, and moreover without formal ownership, land cannot be used as collateral to obtain loans.

Partnerships for upgrading strategies and creating sustainable inclusive value chains

To integrate local communities to supply products to the tourism sector, there is a need to combine demand, supply and market intervention (Ashley and Haysom, 2008). Some initiatives have failed because they focused either on supply by working with farmers, or on demand, by working with chefs but not on both together (Torres 2003). To enhance employment and business gains from the tourism chain, intervention is required on the supply-side, such as creating a positive business environment and supporting micro enterprises. Intervention is also required on the demand-side – e.g. in influencing hotels to buy locally.

Partnerships are one way to link communities with tourism activities. In Botswana, for example community trusts have been established in joint-partnership between communities and international safari companies who have the skills and experience in tourism development (Mbaiwa, 2008). Large-scale development is the precursor of small-scale development (Carter, 1991) hence as tourism development proceeds, indigenous firms, industries and locals gain knowledge and experience (Mbaiwa, 2008). Through interaction with longer-established „global‟ firms, local enterprises gain access to technology, capital, markets, and organization which enable them to improve their production processes, attain consistent and high quality, and increase the speed of response (Gereffi et al., 2005). A basic requirement for upgrading is the strategic intent of the firms involved. Government also has a role to play in fostering upgrading and competitiveness. Market dynamics alone is not sufficient to achieve competitiveness through upgrading; rather the development and rapid diffusion of knowledge can be fostered by policy networks of public and private actors (Scott, 1996).

Since the end of the 1990s, the role of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in sustainable development in general and in alleviating poverty in developing countries in particular is increasingly recognized. At the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg (2002) governments were encouraged to launch new partnerships between state, business and civil society. Partnerships between the public and the private sector in the „western developed‟ context are not a new phenomenon. PPPs constituted an element in the broader process of privatization, accelerated by the Thatcher government in the 1980s. "Broadly

speaking, privatization does not refer merely to the transfer of state-owned enterprises to private investors,

but also to a shift of public sector activities to the private sector" (Sadka 2006, p.2).

The underlying idea of partnerships is that by generating additional knowledge and resources, results can be achieved that benefit all parties, which could not have been achieved on an individual basis (Kolk et al., 2008). Societal actors working together can avoid a future with fragmented policies and dysfunctional initiatives that are incapable of fully meeting societal expectations (Warhurst, 2005). Moreover, partnerships are not only seen as ways of delivering positive development outcomes, but also as new governance mechanisms (Glasbergen et al.,2007).

The typical „western developed‟ PPP is an undertaking which involves a sizable initial investment in a certain facility (a road, a bridge, an airport, a prison) or utilities (such as water and electricity supply), and then the delivery of the services from this facility or utility. Since these activities have some public good features, they

are not privatized once for all; "rather, the state continues to be involved in some way or another" (Sadka 2006, p. 3). The Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs defines partnerships as: "voluntary agreements between government and non government to reach a common objective or to carry out a specific task in which parties share risk, responsibilities, means , competencies and profits" (Ministry of Development Cooperation, 2004)..

The „Partnering Initiative‟ defines partnerships as a cross sector collaboration in which organizations work together in a transparent, equitable, and mutually beneficial way towards a sustainable development goal and where those defined as partners agree to commit resources and share the risks as well as the benefits associated with the partnership[ii].

For PPPs in developing countries the efficient sharing of risks, responsibilities and benefits is of particular importance in this paper. The objective of these PPPs is to accelerate sustainable growth in developing countries by working in tandem both with the public and private sector whereby the public sector focuses on developmental benefits and the private sector focuses on profitability within a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) framework.

From a holistic, multi-stakeholder point of view, partnerships should preferably involve a range of significant actors, including governments, non-governmental actors, international organizations and the private sector. However, this research focuses primarily on PPPs between the private and the public sector in developing countries where the exchange of financial and non-financial resources is important. We define PPPs in developing countries according to the OECD guidelines where partnerships are: a voluntary arrangements that share benefits and risks among partners and combine and leverage the financial and non financial resources of partners towards the achievement for specific goals (OECD, 2006).

Business-community partnerships

During the last decade local private sector development got attention from several perspectives. According to Raufflet et al. (2008) there are three business models addressing poverty alleviation and promoting local private sector development: the social enterprise business model (Bornstein (2004), the base of the Pyramid (BOP) (Prahalad, 2006) and the partnership for development model. Business-community partnerships are becoming important phenomena within developing countries. Especially in the oil and mining sector business-community relations are critical. Both in the mining and in oil sector foreign investors earn relatively an enormous amount of money compared to what community members are earning. This causes friction between the companies and the community and a source for conflict. It is through a tri-sector partnership approach to development and conflict resolution that the needs of all stakeholders can be addressed and conflict can be avoided (Idemudia and Ite, 2006),

According to Loza (2004) the goal of business-community partnerships is to help build the capacity of communities and to provide greater opportunities for active participation in the social and economic arena by those who are historically disadvantaged. Besides there is the aim to build CSR capacity and other social capital (Moon, 2001), which can produce outcomes that would otherwise be difficult to obtain. Raufflet et al. (2008) assessed the impact of local enterprise and global investment models on poverty alleviation and biodiversity conservation. Although the angle was not addressing local private sector development the findings show that the local enterprise models caters for local empowerment while the global investment models provides for financial resource and markets.

BCPs and value chain upgrading

Linking the theory of BCPs with the theory of value chain upgrading, it is observed that PPPs potentially have a role to play in providing enabling conditions for local businesses to upgrade their services and products. By enabling contact with globally linked companies, PPPs may allow local enterprises to overcome obstacles to value chain upgrading by allowing access to transfers of capital, skills, technology, infrastructure etc.

Based on preliminary studies which indicated the main areas of contribution to local business upgrading by BCPs in Tanzania, the five areas of capital, knowledge / skills, markets, infrastructure and land will be examined more closely in this paper. From the partnerships and value chain literature review the following proposition arises:

Proposition: Business-Community Partnerships enable local businesses to overcome obstacles to integration in global value chains if they provide conditions for upgrading by improving access to capital, knowledge, skills, markets, infrastructure and/or land.

Partnership cases in Tanzania

In this study two types of business-community partnership agreements are studied:

- a. Business-initiated (bilateral) agreements

- b. NGO-initiated (multilateral) agreements

A third group of tourism agreements initiated by central government and linked with hunting tourism investors are used as a without partnership case for comparison.

a. Business-initiated agreements In this model the tour operator proposes to a community that an area of land is provided for tourism activities and in return the village receives compensation in the form of a leasing fee and/or an agreed upon fee per tourist bed night. The village is responsible for ensuring that the visiting tourists and their property are safe, and that no activities are carried out that are harmful to the environment and incompatible with tourism activities, e.g. tree-cutting, cultivation and livestock grazing. These agreements typically involve a private sector investor and a village government, with village members being the direct beneficiaries of the partnership.

b. NGO-initiated agreements Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs) are considered under this category of partnerships. WMAs were initiated and continue to be facilitated by international non-governmental organizations concerned with wildlife conservation, specifically World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and African Wildlife Fund (AWF). The agreements typically involve a private sector investor, central and local governments, the village members as beneficiaries, as well as a civil society organization as follows:

Tour operators make an agreement with the Community Based Organization (CBO) of a WMA to use a portion of land to set up a tented lodge for tourists. They invest in physical property, and are involved in promoting the area for tourism activities. They offer compensation to villages, usually based on a bed night fee recommended by the WD.

Villages voluntarily enter into WMA agreements and form a CBO. Sections of land are contributed by member villages of the CBO for wildlife conservation purposes. Cultivation, herding and residential housing are prohibited in these areas. The CBO in return receives a share of revenues obtained from tourism activities carried out within their area.

Central government, or the Tanzania Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism through the Wildlife Division (WD). The government drafts regulations that monitor tourism activities which are carried out outside of National Park areas, and it is also the agency which collects revenues generated from tourism in these areas. The WD is generally responsible for the conservation of wildlife in these areas, and is expected to provide vehicles and human resources for anti-poaching activities.

District governments are involved in an advisory role through a conservation advisory committee for the WMA. The District in collaboration with the WD also plays a role in coordinating anti-poaching activities.

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as AWF and WWF facilitate the process, and play a role in building human and technical capacities for conservation in areas such as resource management planning. They also contribute funds to enable the process of WMA establishment of the WMA and CBOs.

c. The without partnership case: Government-initiated agreement In the without partnership case, agreements are made between the central government and a tourism hunting company. The tour operator makes payment for the use of a hunting concession directly to central authorities, and a portion of the revenues is delivered to the district government. Some of these funds are intended for local development purposes, but amounts received by villages have been reported to be small. The district is expected to assist in anti-poaching, in collaboration with game rangers from the relevant National Park authority.

This model of partnership was chosen as a without partnership case to allow comparison of the performance of business partnerships at the community level. Since in the without partnership case the community or village is not directly involved in signing the agreement, unless the business initiates contact, it serves to show the extent to which formal contracts or agreements, and meeting of ground rules at the local level are necessary for the success of partnerships for development.

Research Design and Case selection

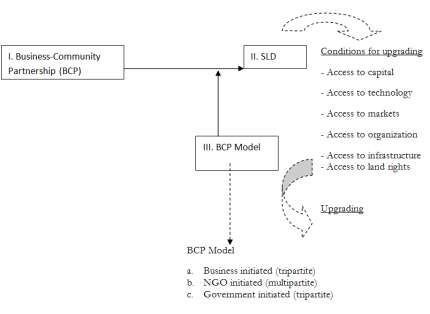

In this study we investigate for different types of partnerships to what extent the conditions for upgrading have been shaped for local private sector development (see figure 1: conceptual framework).

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework

An explanatory multiple-case study design (Yin, 2003) is used to study the relevance of community business partnerships in contributing to local private sector development. This is in line with the research objective of contributing to the value chain literature on upgrading aspects at the local level. Theoretical sampling is used in order to isolate three cases per business community partnership model and to extend relationships and logic among constructs in the study (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007), allow replication (Eisenhardt, 1991), enrich cross-region comparison, create more robust theory to augment external validity, guard against researcher bias, add confidence to findings (Miles and Hubberman, 1994) and to provide a stronger base for theory building (Yin, 2003).

The performance of business-community partnership in relation to sustainable local development will be assessed by comparing the two BCP models with each other (business-initiated and NGO-initiated, with the government-initiated as dummy). Perception based semi-structured interviews were conducted with the key-stakeholders. The unit of analysis is the business-community partnership.

All selected cases are focusing on sustainable tourism development and particularly on local private sector development as a result of tourism activities. In order to assess the performance of the BCP models in the tourism sector in Northern Tanzania the study initially focused on the NGO-initiated BCP models. All the NGO-initiated BCP models which are in existence for more than three years were considered. In total there are three NGO-initiated partnerships in Northern Tanzania, which are in existence for three years or more, which are operating in three different districts. It has been decided to assess all three NGO-initiated BCP models. In order to compare the performance of the NGO-initiated BCP model the study looked also at the business-initiated BCP models, and the government-initiated BCP models in these three districts were used as dummies and reflects a national government signing an agreement with a hunting business company. Communities are officially not involved in these partnerships. The business-initiated partnership is characterized by the fact that it is a partnership of one business with one village. The involved village often leases the land to the involved business. Both conservation and economic development objectives are equally important in these partnerships. The NGO-initiated BCP models are characterized by the fact that more than one village is involved in the partnership as conservation is the main driver for these partnerships and conservation is best done over a larger area with results in a partnership between a business and often 3 to 10 villages. Studying the cases in the three districts provides a means of comparison and an opportunity to identify factors that influence the performance of partnerships which have not previously been considered in empirical studies for the region.

The identified districts are Longido bordering west Kilimanjaro and covering a corridor area linking Kilimanjaro National Park with Amboseli National Park in Kenya. The second district is Babati, located around Tarangire National Park in Tanzania and the third district is the, Serengeti district in Mara region bordering Serengeti National Park.

Data collection

Based on the conceptual framework outlined above, the data required was related to information on the type of business-community partnerships existing in the villages and the extent to which the partnership provided conditions for upgrading in the tourism value chain.

Data was collected using semi-structured in-depth interviews with 60 different actors involved in business-community partnerships. Theoretical sampling was done to ensure that all stakeholder groups i.e. value chain actors and facilitators are fairly represented. Stakeholders interviewed include the investor (tour operator), members of the village government council, village members, district government representatives, NGO representatives, and central government representatives in order to gain their perspectives on the tourism ventures under study. Visits to the research sites further facilitated access to information on the ventures as they allowed access to visual evidence of the outcomes of the partnership, and getting the perspectives of the different stakeholders.

Respondents were always willing to participate and share information. However, language barriers and the difficulty of explaining concepts to individuals living in the margins of society implied that information documented was often from the elite members of the community e.g. village leaders, community based organization leaders, leaders of producer groups, wildlife authorities in the district and central government as well as some NGO officials. Perspectives from the poorest community members were therefore not always easy to obtain.

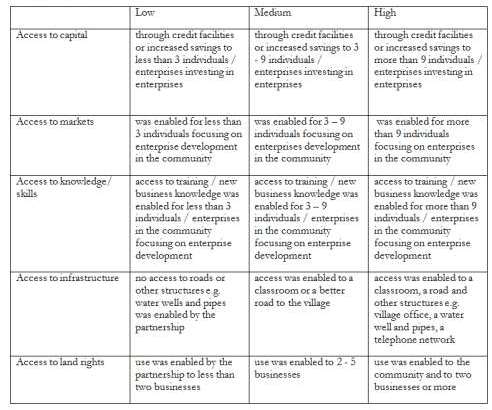

Results collected from the interviews are presented in a table showing the performance of each partnership case relative to each other in terms of improving conditions for upgrading. Rankings were made based on stakeholder perceptions of the level of improving conditions for upgrading. For each partnership case a ranking of HIGH, MEDIUM or LOW was given for all the variables tested according to the respondents‟ perception of the partnership‟s performance, and on the basis of the researcher‟s assessment of the

performance of each partnership case relative to the performance of other cases studied.

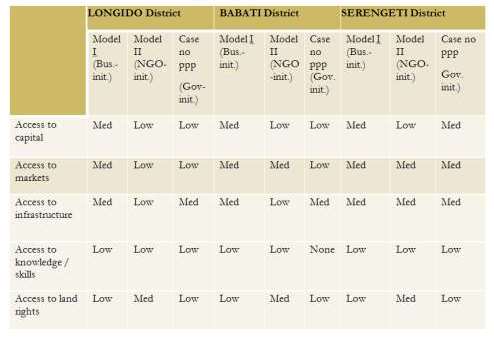

The performance of BCPs in improving value chain upgrading for local businesses

An assessment was made of the contribution of the partnership cases in providing conditions for local business upgrading. Specifically, an assessment was made of the partnership‟s contribution to enable local enterprises to access capital, markets, knowledge / skills, infrastructure and land-use rights. Table 1 shows the findings from the study.

Table 1: Conditions for local business upgrading

Table 1 shows the performance of each partnership case in providing conditions for value chain upgrading. Table 2 provides the key to table 1.

Table 2: Key for Table 1

Analysis

We will now summarize the evidence of the partnership case studies in providing possible upgrading effects for local private sector development. Access to capital by local entrepreneurs in terms of access to bank loans is in all the studied cases absent. However, some substantial savings were made in the business-initiated partnership cases with the community. Capital provided to the communities in all three business initiated cases in the form of money payments per tourist bed nights often amounted to US$50,000 to 90.000 per year (Serengeti District) , excluding donations from philanthropic tourists. As these communities had no direct access to banks the partnership agreement provided them with capital which could be used for value chain upgrading. The less investment of the tourism business is involved the more chance there is for new entrepreneurs to enter the market as well. For example the business-initiated partnership case in Longido shows that links were established with local businesses in terms of the establishment of more guesthouses run by different entrepreneurs as the main entrepreneur had not the means to build more luxury accommodations themselves. In the business-initiated partnership case in Serengeti, access to capital was also relatively high due to a good number of people being employed in tourism. Savings by those employed was converted into capital allowing some local people to start small businesses through informal loans. It was reported that the number of small business had doubled over the past ten years as a result of local spending by people employed by tourism businesses in the village[iii]. These partnership agreements provided means to obtain access to capital which led to a stage of Medium. In all the other cases access to capital was low. The reason for low capital transfers is that the NGO-initiated partnerships involved 3-10 communities providing little earning per community while in the business-initiated partnerships the earnings had not to be shared with other communities. The government initiated partnerships did not involve communities at all, except for the case in the Serengeti, leaving also in these cases the community with no access to capital.

Access to capital is of crucial importance for local private sector development. Partnerships can be an instrument in transferring some money into the local markets. However if the money provided by the tourism business has to be divided over many communities the capital becomes too little to make any significant impact. Although the business-initiated partnerships improved access to savings it did not provide for an access to credit nor that links with banks or MFI‟s were established.

Access to markets remains a difficult issue and is related to access to capital and access to knowledge. Access to markets is in this context defined as getting tourist to buy local products or services. In general, the higher the investments the higher value can be created. Having knowledge over what the tourist wants gives tourism investors an added advantage over local investors who often lack this knowledge and in addition often lack the capital for investment. A first entry level to this tourism market can be created by having tourist buying handicraft directly at the community. The second entry level would be the sourcing by the tourism investor of buying locally vegetables, meat and construction material. Higher up on the value chain ladder is the catering as a restaurant or hotel for the tourism sector and in a way starting to compete directly with the more experienced often foreign tourism investor. In the researched cases, the access to markets was often related to the first level of entering the tourism market or not related at all. All government initiated partnerships showed that no community or entrepreneur was entering the tourism market. When we observed the business-initiated BC partnership and the NGO-initiated BC partnership we found that both do provide a first or second level entry to the tourism market and in one case in the business initiated case in Longido we saw even one entrepreneur developed a small guesthouse. A good example of a second access to market entry level is provided by the Business-initiated partnership in the Serengeti where the tourism investor encourage local sourcing of vegetables, dairy and meat for their staff and sometimes for their clients as well. Also in the business – initiated case in Longido the tourism investor encouraged tourist of buying local made handicrafts.

It can be concluded that Business or NGO initiated partnerships do provide a linkage to the tourism markets already through the nature of the agreement which is a direct agreement in these two partnership-models. However, these linkages were more intensive in the Business initiated partnership than in the NGO – initiated partnership as the linkage between the mainstream business and the one community was more direct and intensive than in the NGO-initiated partnerships were there relations of the mainstream business had to be shared with sometimes 10 communities such as in Longido. However, knowledge alone is not sufficient for communities to understand the market. Knowledge and capital are equally important. We found therefore that business initiated partnerships provided the best entrance to the tourism market as also in the case of access to capital and to a certain extent the access to knowledge scored higher than the other partnership cases.

Some of the business-initiated partnership cases were able to facilitate access to knowledge or skills necessary to establish a tourism related venture. However, this never exceeded entrepreneurship training to more than three enterprises. The partnerships did provide a framework for linkages. In Longido district for example a good level of linkage between the mainstream tourism business and the local businesses exists. Meetings between the community and the mainstream tourism business were done on a twice monthly basis and the mainstream business actively tried to involve the community and contacts with the tourist were high. Some training was provided by the mainstream business. With such linkages and knowledge local businesses came into contact with tourists and saw what tourists demanded, and looked for ways to supply these products. The same was observed in the business-initiated partnership case in Serengeti, there was also a good level of contact with tourists. However, to translate this interaction in business development knowledge leading to new ventures remained very difficult. Only very few businesses were finally established.

In the NGO-initiated partnership cases there were fewer contacts between the mainstream business and the community. However, opportunities for training and acquisition of skills were made possible by having community staff working in the business. Particularly in the management, administration areas and in conservation areas there was some form of training. In this partnership model each village was required to engage village game scouts to monitor the environment, and a handful of these would receive training for the job using funds obtained from tourism activities. In Longido, an accountant and a manager were undergoing training in order to take on tasks in the management of their Community Based Organisation (CBO) which is responsible for the management of the NGO-initiated partnerships. However, the training was not business oriented and did not result in the development of more enterprises in the community.

In the cases without partnership transfers of knowledge and skills in tourism were low often due to a low level of employment, and exposure to tourism per village because of the low numbers of hunting tourists in general. An exception was seen with the Serengeti case without partnership, where the company placed a strong emphasis on local hiring, and had a clear training and career advancement policy. This system enabled the workers to learn and apply new skills quickly.

In general the business-initiated partnerships showed the highest level of linking and provided often for training on the job for staff working in management or conservation jobs. However, very little training was provided on entrepreneurship, and on establishing local businesses catering for the larger tourism value chain.

In most partnership models and cases access to infrastructure was made possible because of tourism activities in the area. In the business-initiated cases access to infrastructure was enabled through land-lease and/or tourist bed-night payments from the tourism investor to the village, which allowed the village to develop infrastructure such as classrooms for a school, or a village office as was the case in Longido district. In the NGO-initiated partnership case in Serengeti the business had dug 54 water wells in the surrounding villages. Some access to infrastructure was enabled even in cases without local partnerships, as central authorities required the tourism investor to invest a minimum of 1000 USD onto the hunting concession, which usually went into building and maintaining of roads[vi]. In the case without partnership in Babati, it was observed that the tourism business, which had its lodge located in a remote area, constructed a local road, which resulted in the community benefiting as well. In some cases, e.g. Babati and Serengeti, the communities benefited from tourism more generally because of their location near internationally famous National Parks, which ensured that the quality of roads leading to them was of a fairly good standard.

Access to infrastructure improved due to the partnership agreements although it can be concluded that the more tourist entering the area the more attention is being given by the government to improve infrastructure but also the more chance communities have in receiving philanthropic aid from well doing tourist. Partnerships itself are not the main instrument in creating better access to infrastructure although it is a good tool to air needs which can be turned into better roads, or the satisfaction of other priorities within the community.

Tourism partnerships have also generally improved access to land rights in rural areas. Especially in the NGO-initiated agreements the partnership regulations stipulated that each village obtains a land title deed before it was allowed to invite tourism investors to their village under the WMA agreement. This pushed the villages to obtain a title which formalized the ownership rights to their land and a first step to individual ownership. However, the further distribution of official registered village land to individual families is not yet done. In the business – initiated partnerships access to land rights was less an issue of importance in the sense that partnership agreements were signed without clearly having official land right what made the legal rights of the communities weaker. In the without partnership case no such regulations were in place at all. Moreover, because the tourism business received the permit to use an area of the village land for hunting through central authorities, the village had effectively less say over uses of their land; hence the community‟s access to land rights was low.

Access to land rights for the rural population is in times when land is becoming scarce an important issue in the many countries in Africa. Partnerships are clearly a stimulus for the local community in obtaining land rights, but not for more individual families. From the point of view of the partnering business, the NGO initiated BCP allowed the business user rights to a section of village land for tourism purposes. These agreements were crucial in order for the business to be established and operate.

Conclusions

These cases highlight the importance of building positive relations between communities and businesses, and the need to ensure that both parties see the benefits of tourism. Conservation of wildlife resources is only possible when villagers see tourism as a real and viable economic opportunity. If wildlife does not generate benefits, or the benefits do not reach the rural population, people are unlikely to conserve nature and wildlife (Arntzen, 2003).

Business-Community Partnerships should enable local businesses to overcome obstacles to integration in global value chains by providing conditions for upgrading by improving access to capital, knowledge / skills, markets, infrastructure or land. This study reveals that partnerships provide conditions for local enterprises to upgrade their activities. Business-initiated partnership cases especially, showed moderate success in areas such as allowing the local community access to the tourist market, access to financial resources and access to infrastructure and access to land rights. In Longido district, some local businesses experienced upgrading. For example, through the support of a local NGO a business venture was established for local women to start to produce jewelry of a standard that could be sold to tourists and also a local guest houses was pushed to improve their standard of service in order to cater to tourists – however, more training and support was required in this area as the standard was still not reaching international levels.

The "without" partnership case in Longido and Babati districts had no effect in terms of product upgrading. One of the reasons was the absence of formal and informal contact between the company and the community, as this was not required in the contract between the company and central government. The cases without partnership that did show some transfers of skills or access to markets were a result of the voluntary initiatives of the company, which started these relations on the basis of strong company ethos on social responsibility.

The NGO-initiated partnership cases provided access to land rights as this was a requirement prior to the village entering the partnership. These partnerships were also contributing towards wildlife management in the villages, which will ensure access to the tourist market in the future, if wildlife numbers are maintained as a result of this partnership in these areas.

All partnership cases showed a moderate contribution to local infrastructure development – from physical infrastructure such as roads, to social infrastructure such as classrooms for schools, village office buildings, and clinics. These improvements were seen even in cases without local partnerships as the investors in hunting tourism companies were required by central authorities to put some investment – of a minimum of 1000 USD per season within their hunting concession, which was used in areas such as maintaining roads.

A noticeable gap for all partnership cases was in enabling access to knowledge on enterprise development. None of the partnerships studied, provided entrepreneurship skills to the community. In addition, none of the partnerships provided facilities to access to capital in a direct way, and in the cases where some access was facilitated it was through a high level of local employment or high cash transfers because of a high number of tourist providing for a sizeable amount of bed-night fees.

It was observed that in cases which were more successful in providing conditions for upgrading, the tourism investor had put in an extra investment to support local enterprises. Examples of such cases were seen in the Longido business-initiated partnership case where the investor actively encouraged their clients to buy local products and in the Serengeti NGO-initiated case where the lodge encouraged the local association to sell more of their produce to the lodge. Hence a conclusion here is that in order for the partnership to be effective in contributing to local value chain upgrading an extra investment of finances, resources and entrepreneurship-skills is required, which may be provided by the investor or by government.

In all partnership cases studied there is a gap, and an opportunity for government – both central and local, to become more actively involved in providing enabling conditions and support that would make it possible for local enterprises to benefit from the presence of an investor linked to international markets in their village. Such support could be in the form of establishing local lending facilities, training and information centers, small business development workshops – all of which would quicken the pace at which local entrepreneurs link together with the globally linked companies.

As discussed, some instances of upgrading were observed as the result of these local partnerships. More support is needed from the Tanzanian government and from globally-linked investors, and perhaps also from NGOs in order to see other types of upgrading take place. If local entrepreneurs acquire new business and tourism-related skills, and are able to acquire new functions within the global tourism value chain, which they currently are not able to fully access, more benefits would be passed on to local communities from tourism. Opportunities for local people to become more directly involved in tourism activities and to start their own accommodation or tourism operations remain untapped if the local people do not acquire capacities to do so.

Overall it can be concluded that the higher the level of engagement in the sense of formal or informal contacts the more chance there is for local private sector development to be linked to the global tourism market. BCP‟s stimulate this engagement. From a local private sector development point of view it is therefore important not to have too many communities being involved in the partnership as this might resolve in evaporation of the required inputs for local private sector development as skills, resources and finances are scare anyhow. However, engagement alone is not enough also the transfer of entrepreneurship knowledge and a provision of access to formal networks for capital are required in future designs of partnerships stimulating local businesses.

References

AMTZEN, J. (2003): "An economic view on wildlife management areas in Botswana", in: CBNRM Network Occasional Paper 11, CBNRM Support Programme SNV/IUCN. [ Links ]

ASHLEY, C. and HAYSOM G. (2008): The Development Impacts of Tourism Supply Chains: Increasing Impact on Poverty and Decreasing our Ignorance, in A. SPENCELEY (ed.): Responsible Tourism, Critical Issues for Conservation and Development, pp. 129-156. [ Links ]

ASHLEY, C., HAYSOM, G., POULTNEY, C., McNAB, D. and HARRIS, A. (2005): The How To Guides: Producing Tips and Tools for Tourism Companies on Local Procurement, Products and Partnerships. Volume 1: Boosting Procurement from Local Businesses, London. [ Links ]

BORNSTEIN, D. (2004): How to change the world: Social entrepreneurs and the power of new ideas, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

CARTER, E. (1991): "Sustainable tourism in the Third World: Problems and prospects", in: Discussion Paper No.3, University of Reading, Reading, pp. 32. [ Links ]

CEBALLOS-LASCURAIN, H. (1996): Tourism, Ecotourism and Protected Areas: The State of Nature-based Tourism around the World and Guidelines for its Development, IUCN, Gland. [ Links ]

EISENHARDT, K. M. (1991): "Better stories and better constructs: The case for rigor and comparative logic, in: Academy of Management Review, Vol. 16, pp. 620–627. [ Links ]

EISENHARDT, K. M. and GRAEBNER, M. E. (2007): "Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges", in: Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 25-32. [ Links ]

FISZBEIN and LOWDEN (1999): Working Together for a Change: Government, Civic, and Business Partnerships for Poverty Reduction in Latin America and the Caribbean, World Bank, Washington. [ Links ]

GLASBERGEN, P., F. BIERMANN, A. Mol (2008): Partnerships, Governance and Sustainable Development, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham. [ Links ]

GEREFFI, G., HUMPHREY, J., STRUGEON, T. (2005): "The governance of global value chains", in: Review of International Political Economy, Vol. 12, No.1, 2005, pp. 78-104. [ Links ]

HALL, C. M. (2007): "Editorial, Pro-poor tourism: Do "Tourism exchanges benefit primarily the countries of the South?", in: Current Issues in Tourism, Vol. 10, Numbers 2 and 3, pp. 111-118. [ Links ]

HELMSING, A. H. J. (2003): "Local economic development: New generations of actors, policies and instruments for Africa", in: Public Administration and Development, Vol. 23, pp. 67-76. [ Links ]

IDEMUDIA, U., and ITE, U. E. (2006): Corporate-Community Relations in Nigeria‟s Oil Industry: Challenges and Imperatives, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 194-206. [ Links ]

JAFARI , J. (2001): The scientification of tourism, in Smith, V L and Brent, M (eds), Hosts and Guests Revisited: Tourism Issues of the 21st Century, Cognizant Communication, New York. [ Links ]

KAPLINSKY, R. and MORRIS, M. (2002): Handbook for value chain research, IDRC. http://www.globalvaluechains.org/docs/VchNov01.pdf, accessed 17 December 2011. [ Links ]

KOLK, A, VAN TULDER, R. and KOSTWINDER, E. (2008): "Business and partnerships for development", in: European Management Journal, 26, pp. 262-273. [ Links ]

LOZA, J. (2004): „Business-Community Partnerships: The Case for Community Organization Capacity Building, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 53, pp. 207-311.

MASSYN, P. J. (2008): Citizen Participation in the Lodge Sector of the Okavango Delta in A. Spenceley (ed.) Responsible Tourism, Critical Issues for Conservation and Development, Earth Scan, London, pp. 205-223. [ Links ]

MBAIWA (2008): The Realities of Ecotourism Development in Botswana, in A. Spenceley (ed.) Responsible Tourism, Critical Issues for Conservation and Development, Earth Scan, London, pp. 305-321. [ Links ]

MILES, M. B. and HUBBERMAN, M. (1994): Qualitative Data Analysis: A Source Book, Sage. [ Links ]

MOON, J. (2001): "Business Social Responsibility: A Source of Social Capital? Reason in Practice", in: Journal of Philosophy of Management, Vol. 1, Number 3, pp. 385-408. [ Links ]

NELSON, F. (2008): Livelihoods, Conservation and Community-based Tourism in Tanzania: Potential and Performance, in A. Spenceley (ed.) Responsible Tourism, Critical Issues for Conservation and Development, Earthscan, London, pp. 305-321. [ Links ]

OECD (2006): Evaluating the Effectiveness and Efficiency of Partnerships, Workshop, Paris: 12 September 2006, ENV / EPOC, 15. [ Links ]

VAN DIJK M.P., PFISTERER, S., VAN TULDER, R. (2010): "Partnerships for Sustainable Development – Effective? Evidence from the horticulture sector in East Africa", Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Netherlands. [ Links ]

PRAHALAD C. K. (2006): The Fortune at The Bottom of the Pyramid, Eradicating Poverty Through Profits, Pearson Education, Inc., New York [ Links ]

RAUFFLET, E., BERRANGER, A., GOUIN, J.F. (2008):" Innovation in business-community partnerships: evaluating the impact of local enterprise and global investment models on poverty, bio-diversity and development", in: Corporate Governance, Vol. 8, Number. 4. [ Links ]

ROGERSON, C. M. (2006): "Pro-poor local economic development in South Africa: The role of pro-poor tourism", in: Local Environment 11, No.1, pp. 37-60. [ Links ]

RYLANCE, A. (2008): Local Economic Development in Mozambique: An Assessment of the Implementation of Tourism Policy as a Means to Promote Local Economies in A. Spenceley (ed.) Responsible Tourism, Critical Issues for Conservation and Development, Earth Scan, London, pp. 27-39. [ Links ]

SADKA, E. (2006): Public-Private Partnerships: A Public Economics Perspective, Working Paper (WP/06/77), International Monetary Fund, Washington. [ Links ]

SCOTT, A. J. (1996): "Regional motors of the global economy", in Futures,Vol. 28, pp. 391-411. [ Links ]

SIMSPN, M. C. (2008): "An integrated approach to assessing the impacts of tourism on communities and sustainable livelihoods", in: Community Development Journal, Vol 43. [ Links ]

STERR, M. (2003): The Impact of Business Linkages on Sustainable Development, an assessment of four European Partnership Programmes, Leicester. [ Links ]

TORRES, R. (2003):" Linkages between tourism and agriculture in Mexico", in: Annals of Tourism Research, Vol 30, No. 3, pp. 546-566. [ Links ]

VISSEREN-HAMAKERS, I. J., Arts, B., GLASBERGEN, P. (2007):, Partnerships as a Governance Mechanism in Development Cooperation: Intersectoral North-South Partnerships for Marine Biodiversity‟, in GLASBERGEN, P., BIERMANN, F., and MOL, A.P.J., Partnerships, Governance and Sustainable Development. Reflections on Theory and Practice, Edward Elgar, Cheltham. [ Links ]

WARHURST, A. (2005): "Future roles of business in society: the expanding boundaries of corporate social responsibility and a compelling case for partnership, in: Futures, Vol. 37, pp: 151-168. [ Links ]

YIN, R. (2003): "Applications of Case Study Research", in: Applied Social Research Methods Series, Volume 34, Thousand Oaks, Sage, New York. [ Links ]

Submitted: 09.02.2011

Accepted: 12.09.2011

Notes

[i] World Travel and Tourism Council Report 2010

[ii] http:www.theparntering initiative.org/whatispartnering.jsp as a t 4-12-08