Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Tourism & Management Studies

Print version ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.9 no.1 Faro 2013

Strategic process and organizational knowledge: Towards a pattern of strategic knowledge management

Processo estratégico e conhecimento organizacional: em direção a um padrão de gestão estratégica do conhecimento

Damião Eneias de Melo dos Santos1, Adriana Roseli Wünsch Takahashi2

1 União Dinâmica de Faculdades Cataratas – UDC, Brazil, damiaostos@yahoo.com.br;

2 Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brazil, adrianarwt@terra.com.br

ABSTRACT

Knowledge Management has played an important role for organizational strategic processes. Thus, this work sought to examine the relation between strategic process and KM in the organization of an alimentary sector located in Brazil, namely, the company Frimesa. Through semi-structured interviews and non-participant observation, the proposed problem was instrumentalized. For that, the strategic process steps of this organization’s dairy line were identified from certain events; the knowledge flow and its application in the identified steps of the strategic process were investigated; and, finally, it was verified whether this relation configured a KM sample by means of promotion and knowledge sharing practices. The results of the pattern proposed point to the existence of a relation between strategic process and knowledge flow, with KM figuring as support for this relation, suggesting the existence of a strategic knowledge management.

Keywords: Strategic process, knowledge flow, knowledge management.

RESUMO

A Gestão do Conhecimento (GC) tem tido um importante papel no processo estratégico organizacional. Assim, este trabalho procura examinar a relação entre processo estratégico e GC em uma organização do setor alimentício localizada no Brasil, denominada Companhia Frimesa. Por meio de entrevistas semi-estruturadas e observação não participante, o problema proposto foi instrumentalizado. Para isso, os passos do processo estratégico da linha de laticínios desta organização foram identificados a partir de certos eventos; o fluxo de conhecimento e sua aplicação nos passos identificados do processo estratégico foram investigados; e, finalmente, foi verificado se esta relação configurou um caso de GC por meio da promoção e praticas do compartilhamento de conhecimento. Os resultados do padrão proposto mostraram a existência de uma relação entre processo estratégico e fluxo de conhecimento, com a GC atuando como suporte para esta relação, sugerindo uma gestão estratégica do conhecimento.

Palavras-chave: Processo estratégico, fluxo do conhecimento, gestão do conhecimento.

1. Introduction

This work proposes a reference pattern that integrates practices concerning the strategic process and knowledge flow to sustainable creation of value at organizational level. This relation has to be explored by means of KM, using a multilevel perspective of temporal practices. The pattern also proposes the integration of elements traditionally covered in literature, in terms of dynamic process, developing organizational strategies and using the knowledge flow and their practices. The relations between practices are represented by the integration of factors that exist in organizational structures through strategic process, knowledge flow, related KM practices and communication among their main actors (Certo & Peter, 1993; Patriotta, 2003; Schlesinger et al., 2008). This approach produces a more refined comprehension of how dynamics between strategic process and knowledge flow, as well as the KM practices, may generate the creational capacity of a Strategic Knowledge Management (Terra, 2008) and also raise the level of comprehension of how the organizations may enrich their search for an efficient strategic sustainability.

2. Literature review

2.1 strategic process

Most studies that deal with process (Van De Ven, 1992; Certo & Peter, 1993; Pettigrew, 1997) seek ways to describe, analyze and/or explain "how", "what" and "why" there is a sequence of individual and collective actions, inserted in a dynamic process; it is turned into an interpretation of the moving social reality, whose actors shape and are shaped, resulting in a legacy in which the past is alive in the present, which can shape the emerging future. Therefore, process can be understood as a sequence of individual and collective events, actions or activities that unfold over a period of time, inserted in a dynamic environment. For Certo and Peter (1993), the entire strategic process must be developed based on five steps.

Current trends on studies involving strategic processes (Hutzschenreuter & Kleindienst, 2006; Langley, 2007; Bulgacov, Coser, Baraniuk, Prohman, & Souza, 2007), defend the idea that we need to overcome the dichotomy between "thinking" and "acting". Organizational strategy is to be seen as a continuous process, involving complex reasoning and implementation through projects. Sminia (2009) understands that all innovation of a process created over a given time can be considered a success when it becomes institutionalized. A contextual approach of the strategic process, the way it is presented, involves in its journey the appropriation of knowledge, which has an important role in this process, since organizations are here construed as featuring a knowledge range from several types (Pettigrew, 1997). Knowledge and its integrative flow have a key role in this process, and require a greater depth of study.

2.2 organizational knowledge

The study of organizational knowledge, to some researchers (Davies & Botkin, 1994; Takahashi, 2007; Angeloni, 2008; Spender, 2008; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 2008; Rodrigues, 2008; Carbone, Brandão, Leite, & Vilhena, 2009), takes knowledge as the essential fuel for growth and organizational development. For Sanchez and Heene (1997), the organizational knowledge can be understood as a shared set of beliefs about causal relations maintained by persons inserted in a particular group. Fleury and Oliveira (2008) understand that Brazilian organizations face the challenge of competing in a world where knowledge, and not work force or abundant and cheap natural resources, is a competitive advantage. Thus, the company’s core competencies consist of knowledge sets and all knowledge is the result of a learning process. Therefore, knowledge can be understood as part of the organization's content. The pursuit of efforts to retain and use this knowledge in organizations involves management processes, more specifically the KM.

2.3 knowledge management

KM is now in the center of strategic management studies of organizations, whose environment is constantly changing (Eisenhardt & Santos, 2002; Lyles, 2008; Oliveira, 2008; Ichijo, 2008; Terra, 2008). Such changes are happening in the external environment, in multiple dimensions and at a fast pace, requiring rapid and continuous changes in the organization. Fleury and Oliveira (2008) understand that KM makes an important contribution to understanding how intangible resources might constitute the basis for a competitive strategy, as well as to the identification of strategic assets that will ensure superior results for the company. Therefore, works on strategic knowledge management highlight the importance of KM to the organizational strategic processes. For Carbone et al. (2009), the management of intangible assets in the organizations, such as KM, has aroused a strong interest in academic and business studies (Gantman, 2010). KM can be defined as the process by which an organization consciously and systematically collects, organizes shares and analyzes its knowledge collection, in order to achieve its strategic goals (Falcão & Bresciani, 1999). The search for patterns that have a KM relation to organizational strategies, focusing on strategic process, is necessary in view of the importance that their practices may produce to the quest for a sustainable and competitive advantage. Therefore, when the presupposition of existing relations between strategic process and KM is assumed, investigating how these relations happen in organizational context is behooved.

2.4 strategic process and knowledge management

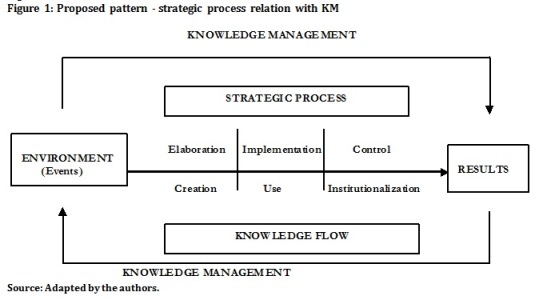

Fleury and Oliveira (2008) understand strategic knowledge management as the task to identify, develop, disseminate and update knowledge strategically relevant to the company, either through internal or external processes to the companies. This implies a perspective, to the company, that understands knowledge as its main strategic asset and that the main results in terms of superior performance will happen due to KM. A pattern developed by Patriotta (2003), called knowledge cycle, is based on the processes of creation, utilization and institutionalization of knowledge, which leads to the production of knowledge results. According to this pattern, the main contents of knowledge have been identified as being: projects, routines and common sense. This knowledge articulation process pattern presented by Patriotta (2003), developed into a cycle of three phases, is related, in this article, to Certo and Peter’s (1993) studies about strategic process, developed on the basis of three interrelated steps of creation, implementation and control. Therefore, based on a proposal for integrating these concepts, developing a pattern that may enable researching and understanding the importance of strategic management of knowledge is sought.

2.5 integrated pattern of strategic process and km

Based on a review of the literature, the integration of strategic process phases was sought (Certo & Peter, 1993), with the knowledge cycle proposed by Patriotta (2003), of organizational knowledge creation, use and institutionalization. The pattern proposed is shown in Figure 1.

According to Certo and Peter (1993), organizational environment can be understood as the set of all factors (events), both internal and external to the organization, which may affect its development to achieve its objectives. This concept is allied with Zarifian’s study (2001), which interprets the events in two ways: (a) from their internal production systems and (b) from the environmental context (external). Finally, Zarifian (2001) points out that an organization inserted into a universe of events must have the perception that things are constantly changing and it is no longer possible to be based on simple repetition of activities, which requires the acquisition of new knowledge and experience, leading to a constant cycle of new events. The result, in this pattern, is parsed through the verification of what remained in the organizational memory on this process (Hedberg, 1981) and the knowledge-based practices that have been institutionalized (Patriotta, 2003). Methodologically, the deconstruction of a strategic process, resuming its story from the event(s) that drove to it, seems to be a rich way of understanding the process and the knowledge flow, their interaction and the identification of a KM presence.

3. Methodology

As for the methodology, the approach of this research is qualitative (Creswell, 2007) and descriptive (Cooper & Schindler, 2003). The case study is appropriate when there is lack of control over the events as well as when the phenomenon analyzed is inserted in some real-life context.

This work sought to examine the relation between strategic process and KM in the organization. The strategy adopted was a case study (Yin, 2005; Eisenhardt, 1989). One company was selected from the food industry in Medianeira town, State of Paraná, Brazil, for this study. One second company of the same sector was used as pre-test. The study adopted a temporal perspective with longitudinal perspective and a transversal perspective in the year of 2010 (Neuman, 1999); transversal because the data were collected only once before being analyzed and reported (Collis & Hussey, 2005), and longitudinal approximation because some data were related to past situations (Neuman, 1999), for example, the situations that refer to the emergent strategies based on knowledge use in a systemic way (KM). The level of analysis is organizational and the unit of analysis is composed by the members of the organization, focusing on strategic levels. The data were collected through semi-structured interviews, in order to seek the participants’ perceptions and experiences. The interview script was submitted to a pre-test in Ninfa organization, also within the alimentary sector of Medianeira (Brazil), which results supported the reorganization of the script. Frimesa industry was chosen among the three existing companies in the region, by the accessibility criterion. Twelve managers and employees of the dairy sector of the industry were interviewed during the period between December 2010 and January 2011. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and codified. Documental research and non-participant observation were used as well. These data were submitted to triangulation in order to assure their validity. Secondary data were also used, such as the final report from the Organization of TOP Excellence – Commercial and Industrial Association of Medianeira (ACIME) in the year of 2009.

The data analysis was performed by means of content analysis (Bardin, 1979), and interactive analysis of data, content and theory. Lastly, the triangulation of sources of evidence was made, aiming to increase reliability and consistency (Stake, 1994).

4. Main results

4.1 the perception of external and internal events at frimesa

The perception of external and internal events at Frimesa (Zarifian, 2001), researches on the sector’s competition and competitiveness (Porter, 2009), combined with the fact that the company was navigating in "red oceans" (Kim & Mauborgne, 2005), culminated in the radical change of the company's overall strategic goal, that was previously aimed at "producing a million liters of milk", and decided to focus on milk’s "quality and earned value". This change resulted in the need to seek the knowledge necessary to readjust strategic planning, as well as a whole new strategic process. The search for industrial restructuring, allied with the fact that Brazil is coming into an era of economic stabilization, which allowed an expansion in its consumers’ purchase capacity, confirms the studies carried out by Guarido (2000), which signaled, to the Brazilian food industry, the need for readjustment, seeking new standards for productivity, quality and technological modernization, compatible with the new situation that had been outlined on the market.

4.2 strategic process elaboration at frimesa

The elaboration of a new strategic process began in 2005, with the search for specialized counsel by Frimesa, such as, for example, a company to develop strategic planning. A branding company, specialized in brands development, was also searched, which helped the study of all packaging used by Frimesa’s dairy industry. With regard specifically to Frimesa’s strategic planning, a business advisory company from Curitiba was hired. This strategic redirection at Frimesa’s company, aligned with strategic planning and its implantation’s updating and adaptation, are related to the concepts defended by Mintzberg (2004) in his studies about Learning School as options to the development of new strategic processes.

With an integrative vision, the training of professionals who would turn the transformation of new strategic processes into reality was sought internally; at the same time, professionals with necessary knowledge to occupy supervision positions, and capable of contributing to development and implementation of pursued new strategic processes, were sought in external market. The objectives of this initiative would be to share knowledge formally obtained as well as experiences of practices developed in other industrial dairy units, in which they have worked, aiming at the integration with other collaborators during new strategic process established by Frimesa. Such observations link with the studies carried out by Nonaka and Takeuchi (2008), as regards knowledge creation and dissemination within a process of constructing new knowledge, as well as studies carried out by Patriotta (2003), who believes that this creation process is within a broad flow of knowledge, in which creation is a generation process that identifies the sources and agents involved in the knowledge-related phenomena production.

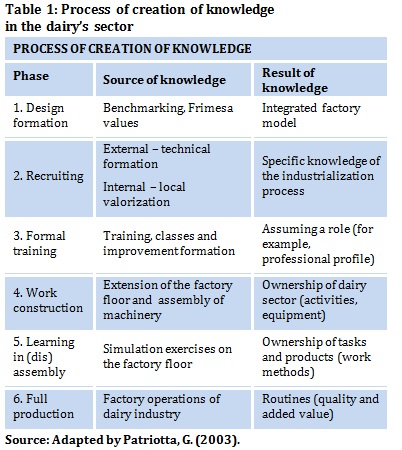

Frimesa’s prevailing human resources policy, today, is to value its internal public, seeking, when possible, professionals trained by the organization itself. Therefore, when knowledge pursuit in the strategy process elaboration phase was examined, it was noted that it was divided into two phases. First there was a major effort to map the organization’s existing internal capabilities. This perception is related to the studies conducted by Carbone et al. (2009), which agree that the organizational managers recognize that, in their own companies, there are resources of great potential, which are: knowledge, know-how and benchmarking (best practices). These resources, for Frimesa, have been recognized through policies of incentive and valorization for its collaborators. In a second phase, Frimesa began to seek out professionals who would be strategically useful for this new industrial phase that had been idealized, even as, to the formation of certain professionals, there are essential technical criteria to create these experiences and to be recognized as valuable. Thus, based on the practices examined in this elaboration stage, in which knowledge was supported, two major points were observed: source and knowledge result in six dimensions (Patriotta, 2003).

Thus, based on the analyzed practices in this phase of elaboration and on the knowledge which supported them, two issues of great importance were observed: the source and result of knowledge in six dimensions (Patriotta, 2003). Table 1 synthesizes the chronological advances noticed, highlighting the sources of knowledge associated to the results of each phase in the Frimesa dairy’s sector.

The strategic process stage was concluded with the arrival of the condensed milk production machine at the Cheese Manufacturing Unit in Marechal Candido Rondon, and on the receipt of the equipment purchased from a refrigerated factory from Curitiba to Matelandia’s Refrigerated Industrial Unit, once the focus turned to the strategic process implementation stage.

4.3 strategic process implementation of frimesa’s dairy industry

The strategic process at Frimesa’s dairy industry was gradually implemented because Matelandia’s Refrigerated Industrial Unit, for example, needed to be expanded to accommodate the new machines purchased. As soon as they had been delivered, the collaborators started the identification, operation and troubleshooting solution training of these equipments. New professionals, hired to facilitate the implementation of this strategic process stage, guided the necessary procedures and catalogued practices that should be followed, which would be ruled in a later process of recording activities that should be used again. This search to establish procedure standards for better practices are allied with the studies carried out by Kardec, Arcuri and Cabral (2002), who define the benchmarking actions as a process of identification, knowledge and adaptation of excellent practices and processes to help organizations improve their performance. With respect to other supply chain components, there was also a great suppliers’ involvement in the implementation phase of this new strategic process. Frimesa, in its first year of activity with this new strategic process, managed to achieve all goals and objectives previously established by strategic planning. One of the key success factors in the company’s new strategy implementation process, observed in this work, was the members’ involvement in supplying chain, from the raw material supplier, which is the milk producer, passing by the machine operator, and reaching the Chief Executive Officer. Such involvement has generated a propitious environment to the creation of several committees, such as the Information Technology Committee and the Committee for New Products Development, making the company more cross-functional and dynamic.

4.4 strategic process control at frimesa’s dairy industry

In 2005, the senior management, based on the company’s strategic planning, established guidelines and objectives that showed the way to the achievement of goals. To their control, control indexes and verification items were established. As an example of control index to Frimesa’s Dairy Sector, it was established as a target, with respect to tangible resources invested in this sector, that 85% of machinery and equipment productive capacity should be used and, in 2010, the dairy industry reached 86% of its installed capacity, surpassing the expectations set out as targets.

A tool considered of great importance to the various controls established in Frimesa’s new strategic process, was the implantation, throughout the whole company, of the control for Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP), developed by one of the collaborators, a specialist in this area, who has received eight years’ training in the largest American meat industry. Another mechanism developed for controlling activities was the Customer Service, which reports monthly and, along with Quality Control, monitors to find failures and where things can be improved. With respect to the environment, Frimesa has an Environmental Management Department.

Controlling Frimesa’s staff activities has been held by its human resources sector, based on the posts descriptions, i.e. the institutionalization of what the collaborator should do, by performance indicators, as well as by verification indexes. According to Frimesa’s direction, among several control processes which were standardized in the company’s dairy sector, none had a more positive performance feedback than the financial one. Developments in the invoicing of this sector contributed to the significant increase in the company's overall revenues, that is, their profitability. Table 2 shows this evalution.

The knowledge that became necessarily fundamental over the organizational strategic process occurred at Frimesa, which resulted from the learning process described in the studies about organizational learning by Takahashi (2007), were guided and solidified by the use of management tools as the PDCA (plan–do–check–act or plan–do–check–adjust), the Strategic Planning, and ISO 9001 Certification. There was also a range of critical analysis in its governing body, which had been considered by the company’s management to be a major evolutionary step that Frimesa accomplished. Among the areas within the company was observed an interoperability, where one is always someone’s supplier who in turn is their consumer, and someone is always the consumer of a product that someone supply.

These relations demonstrate that there is a constant concern with the internal client of the organization, in order that the entire set is produced with quality and added value, becoming an institutionalized culture. It was possible to perceive with this research that the company management, after implementing the new organizational processes, interpreted human resources as a resource of great strategic value for the objectives defined in its planning. This perception of the management of Frimesa finds relation to the studies on RBV of the organizations defended by Barney and Hesterly (2007), who understand that the creation of a model of strategic performance focusing on the resources and capacities that can be controlled by a company can provide a source of sustainable competitive advantage.

Table 3 synthesizes the chronologic advances of the relation between the strategic process and the knowledge flow, yet highlighting the concepts defended by Patriotta (2003), who sees the organizational knowledge as something that is never a perfect reality, but rather is always under construction. This constructionist view focuses on the knowledge movement, where the cycle emphasizes the process of evolution, and not only conversion.

Table 3

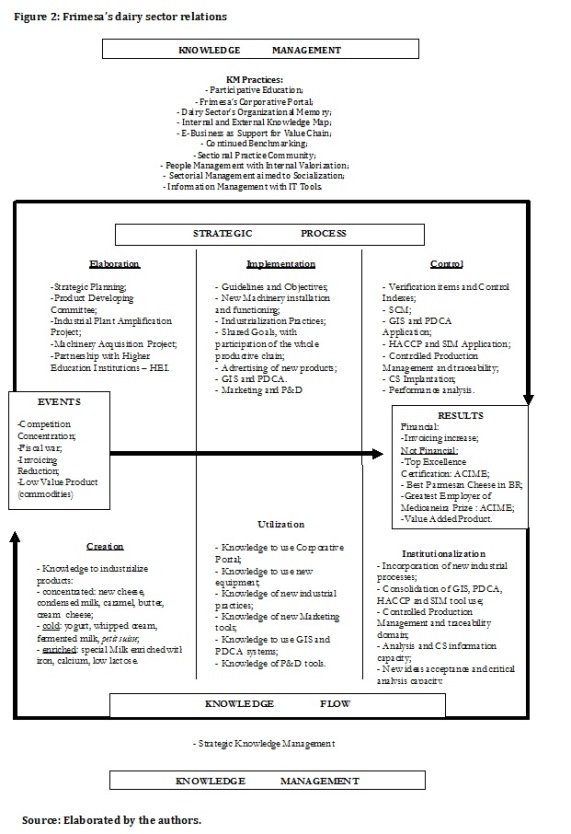

4.5 strategic process and relations with km

Relations between the studied strategic process and KM were analyzed, during the survey, through the investigation of organizational practices (Schlesinger et al., 2008), as their occurrence presence and form. The present practices were: knowledge enterprise portals, organizational memory, knowledge map, Benchmarking, E-business, practice communities, people management, talking management and information management. The unidentified practice was the corporate education. In general, it can be observed that KM practices were considered of great importance by respondents, implanted almost totally, outlining a strategic process of KM (Whittington, 2006; Terra, 2008; Ferraresi, Santos, Frega, & Pereira, 2010). Knowledge, used consistently, gave significant support to the process, impacting on Frimesa’s financial and non-financial results, as the model expanded in Figure 2.

The logic of this cycle is that once an event arises (Zarifian, 2001), within the competitive environment in which the organization is inserted (Kim & Mauborgne, 2005; Porter, 2009), the organization mobilizes its internal resources (Barney & Hesterly, 2007), through strategic process interface (Certo & Peter, 1993), with knowledge flow (Patriotta, 2003), in order to pursue strategic results (Whittington, 2006). The articulation of this cycle has generated, for the company’s strategist, an individual learning (Mintzberg, Ahlstrand, & Lampel, 2000), extending its strategic knowledge and organizational learning for the company (Takahashi, 2007), increasing their intellectual capital (Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Sveiby, 1997); returning this cycle as Strategic Knowledge Management (Terra, 2008), which is renewed when there is a new event that interferes in the organization’s strategic content.

The recognition of the effort of searching for a quality product with added value both for the Direction of the Dairy Sector of Frimesa and their main collaborators, revealed itself in tangible aspects as the certification of the Frimesa Parmesan Cheese, elected as the best cheese in Brazil in the 37 th National Contest of Dairy Products held in the 27th National Dairy Congress.

5. Conclusions

The research demonstrated that there are gaps to be filled regarding the relations between strategy and knowledge, between the strategic process of the organizations and KM. Although several studies have been conducted, whether quantitative or qualitative, the different cultural contexts and contexts of the sector hamper comparisons between some results. Even so, some contributions could be verified in this research. The model analyzed demonstrated a complex relation, but existing between the categories.

The evidences that KM permeates all the relations confirm the statement that knowledge is the main resource of the organizations, since the impact of knowledge strategic management in other process enabled to understand that this resource potentiates the activities connected to quality generation and added value for the companies. Knowledge strategic management can be understood as the element that provides support, through the interface between the steps of strategic process and knowledge flow, understanding it as a task to identify, develop, disseminate and update strategically relevant knowledge for the company. It is important to also emphasize that the collaborators, holders of knowledge, had a differentiated treatment by the Top Management of Frimesa.

The results obtained allow understanding that the strategic knowledge management contributes positively to the development of the organizations’ strategic process. This happens due to the direct effects of the practices related to KM, that facilitate knowledge creation, sharing and application, regarding aspects of knowledge flow in the stages of the new strategic process, elaborated, implemented and controlled by the company. It was verified whether this relation configured a KM sample by means of promotion and knowledge sharing practices. The results of the pattern proposed point to the existence of a relation between strategic process and knowledge flow, with KM figuring as support for this relation, suggesting the existence of a strategic knowledge management.

Among the limitations of this research is the results’ restriction to the case studied and the researcher’s subjectivity, although this was minimized by the use of search protocol techniques and data triangulation. However, it is noteworthy that this research can bring relevant contributions to unveiling the relationship between the strategic process and the knowledge flow, whose practices permit an advance in the KM presence and contribution analysis in strategy.

Regarding future research, it is suggested that studies that strengthen the relation between strategy, knowledge, organizational learning and KM should be undertaken. Further analysis of the creation processes, use and institutionalization of knowledge (through theoretical-empirical quantitative research) for the identification of KM practices is recommended as a strategic focus.

Note: Suported by Fundação Araucária – Paraná – Brazil

References

Angeloni, M. T. (2008). Organização do Conhecimento. São Paulo: Saraiva. [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (1979). Análise de Conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70. [ Links ]

Barney, J. B., & Hesterly, W. S. (2007). Administração estratégica e vantagem competitiva. São Paulo: Pearson Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Bulgacov, S., Coser, C., Baraniuk, J., Prohman, J. I. P., & Souza, Q. R. (2007). Administração Estratégica: Teoria e Prática . São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Carbone, P. P., Brandão, H. P., Leite, J. B. D., & Vilhena, R. M. P. (2009). Gestão por Competências e Gestão do Conhecimento. Rio de Janeiro: FGV. [ Links ]

Certo, S. C., & Peter, J. P. (1993). Administração Estratégica: Planejamento e Implantação da Estratégia. São Paulo: Makron Books. [ Links ]

Collis, J., & Hussey, R. (2005). Pesquisa em Administração: um Gria Prático para Alunos de Graduação e Pós-Graduação (2ª. ed.). Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

Cooper, D.R., & Schindler, P.S. (2003). Métodos de Pesquisa em Administração. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. (2007). Projeto de Pesquisa: Métodos Qualitativo, Quantitativo e Misto (2ª. ed.). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Davies, S., & Botkin, J. (1994). The Coming of Knowledge-Based Business. Harvard Business Review, September-October, 165-170. [ Links ]

Edvinsson, L., & Malone, M. (1997). Intellectual Capital: Realizing Your Company’s True Value by Finding it’s Hidden Roots. New York: Harper Collins. [ Links ]

Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building Theories from Case Study Research. Academy of Management Review, 14, 532-550. [ Links ]

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Santos, F. M. (2002). Knoledge-Based View: A New Theory of Strategy?. In A. Pettigrew, H. Thomas, & R. Whittington (Eds.), Handbook of Strategy and Management (pp. 139-164). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Falcão, S. D., & Bresciani Filho, E. (1999). Gestão do Conhecimento. Revista da III Jornada de Produção Científica das Universidades Católicas do Centro-Oeste. Goiânia: Universidades Católicas do Centro-Oeste. [ Links ]

Ferraresi, A. A., Santos, S. A., Frega, J. R., & Pereira, H. J. (2010). Gestão do Conhecimento, Orientação para o Mercado, Inovatividade e Resultados Organizacionais: um Estudo em Empresas Instaladas no Brasil . XXXIV Encontro da ANPAD, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. [ Links ]

Fleury, M. T. L., & Oliveira, M. M., JR. (2008). Gestão Estratégica do Conhecimento: Integrando Aprendizagem, Conhecimento e Competências. São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Frimesa Cooperativa Central (2010). Relatório Anual 2009. Medianeira-Paraná: Autor. [ Links ]

Gantman, E. R. (2010). Scholarly Management Knowledge in the Periphery: Argentina and Brazil in Comparative Perspective (1970 – 2005). Brazilian Administration Review, 7, 115 – 135. [ Links ]

Guarido Filho, E. R. (2000). Influências Contextuais e Culturais Sobre a Aprendizagem Organizacional: um Estudo no Setor Alimentício do Paraná (Masters Dissertation, Universidade Federal do Paraná, 2007). [ Links ]

Hedberg, B. (1981). How Organizations Learn and Unlearn. In P. Nystron, & W. Starbuck (Eds.), Handbook of Organization Design (pp. 3-27). Oxford: Oxford University. [ Links ]

Hutzschenreuter, T., & Kleindienst, I. (2006). Strategy-Process Research: What Have We Learned and What Is Still To Be Explored. Journal of Management. 32, 673-720. [ Links ]

Ichijo, K. (2008). Da Administração a Promoção do Conhecimento. In I. Nonaka, & H. Takeuchi (Eds.), Gestão do conhecimento (pp. 201-216). Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

Kardec, A., Arcuri, R., & Cabral, N. (2002). Gestão Estratégica. Rio de Janeiro: Qualitymark. [ Links ]

Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (2005). A Estratégia do Oceano Azul: Como Criar Novos Mercados e Tornar a Concorrência Irrelevante. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Langley, A. (2007). Process Thinking in Strategic Organization. Strategic Organization, 5, 271-282. [ Links ]

Lyles, M. A. (2008). Aprendizagem Organizacional e Transferência de Conhecimento em Joint Ventures Internacionais. In M. T. L. Fleury, & M. M. Oliveira Jr. (Eds.), Gestão Estratégica do Conhecimento: Integrando Aprendizagem, Conhecimento e Competências (pp. 273-293). São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Mintzberg, H. (2004). Ascensão e Queda do Planejamento Estratégico. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

Mintzberg, H., Ahlstrand, B., & Lampel, J. (2000). Safári de Estratégia: Um Roteiro pela Selva do Planejamento Estratégico. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

Neuman, W.L. (1999). Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (3ª. ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Nonaka, I. & Takeuchi, H. (2008). Gestão do Conhecimento. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

Oliveira, M. M. (2008). Competências Essenciais e Conhecimento na Empresa. In M. T. L. Fleury, & M. M. Oliveira Jr. (Eds.), Gestão Estratégica do Conhecimento: Integrando Aprendizagem, Conhecimento e Competências (pp. 121-156). São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Patriotta, G. (2003). Organizational Knowledge in the Making: How Firms Create, Use, and Institutionalize Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Pettigrew, A. M. (1997). What is a Processual Analysis?. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 13, 337-348. [ Links ]

Porter, M. (2009). Competição. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, S. B. (2008). De Fábricas a Lojas de Conhecimento: as Universidades e a Desconstrução do Conhecimento sem Cliente. In M. T. L. Fleury, & M. M. Oliveira Jr. (Eds.), Gestão Estratégica do Conhecimento: Integrando Aprendizagem, Conhecimento e Competências (pp. 86-117). São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Sanchez, R., & Heene, A. A. (1997). Competence Perspective on Strategic Learning and Knowledge Management. In A. Heene, & R. Sanchez (Eds.), Strategic Learning and Knowledge Management (pp. 3-15). Chichester: John Wiley. [ Links ]

Schlesinger, C. C. B., Reis, D. R., Silva, H. F. N., Carvalho, H. G., Sus, J. A. L., Ferrari, J. V. et al. (2008). Gestão do Conhecimento na Administração Pública. Curitiba: Instituto Municipal de Administração Pública (IMAP). [ Links ]

Sminia, H. (2009). Process Research in Strategy Formation: Theory, Methodology and Relevance. International Journal of Management Reviews, 1, 97-125. [ Links ]

Spender, J. C. (2008). Gerenciando Sistemas de Conhecimento. In M. T. L. Fleury, & M. M. Oliveira Jr. (Eds.), Gestão Estratégica do Conhecimento: Integrando Aprendizagem, Conhecimento e Competências (pp. 27-49). São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Stake, R. (1994). Case Studies. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln, (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 236-247). London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Sveiby, K. E. (1997). The New Organizational: Managing and Measuring Knowledge-Based Assets. San Francisco: Barrett-Koehler. [ Links ]

Takahashi, A. R. W. (2007). Descortinando os Processos da Aprendizagem Organizacional no Desenvolvimento de Competências em Instituições de Ensino. (Doctoral dissertation, Universidade de São Paulo, 2007). Retrieved from http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/12/12139/tde-17102007-160130/pt-br.php [ Links ]

Terra, J. C. C. (2008). Gestão do Conhecimento: Aspectos Conceituais e Estudo Exploratório sobre as Práticas de Empresas Brasileiras. In M. T. L. Fleury, & M. M. Oliveira Jr. (Eds.), Gestão Estratégica do Conhecimento: Integrando Aprendizagem, Conhecimento e Competências (pp. 212-241). São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Van De Ven, A. H. (1992). Suggestions for Studying Strategy Process: a Research Note. Strategic Management Journal, 13(S1), 169-188. [ Links ]

Whittington, R. (2006). O Que é Estratégia. São Paulo: Thomson Learning. [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. (2005). Estudo de Caso: Planejamento e Métodos. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

Zarifian, P. (2001). Objetivo Competência: Por Uma Nova Lógica. São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Article history

Submitted: 14 June 2012

Accepted: 15 November 2012