Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.9 no.1 Faro 2013

Who’s buying organic food and why? Political consumerism, demographic characteristics and motivations of consumers in North Queensland

Quem está comprando alimentos orgânicos e porquê? Consumerismo político, características demográficas e motivações dos consumidores de North Queensland

Breda McCarthy1, Laurie Murphy2

1 Lecturer in Marketing, James Cook University, Australia, breda.mccarthy@jcu.edu.au;

2 Senior Lecturer in Tourism, James Cook University, Australia, laurie.murphy@jcu.edu.au

ABSTRACT

The organic food market is one of the fastest growing food sectors in Australia, with growth rates in the domestic retail market averaging 50% from 2008 from 2010 (Australian Organic Market Report, 2010). This paper focuses on identifying the demographic characteristics of organic food buyers, the motivational factors that drive the purchase of organic food and the role of political citizenship in food choices. The paper found that the organic food buyer was generally female and well educated, but age, income and presence of children in the household were not distinguishing traits. The study suggests the political consumerism is a driving force for organic food consumption, which was expressed in a distrust of corporations; lack of faith in government; wider concerns over patterns of agricultural land use within the context of sustainability and tendency to engage in boycotts and sign petitions. Variables such as taste, product freshness and animal-welfare were important motivating factors. While consumers have enough knowledge to distinguish between conventionally-grown food and organically-grown foods, there are gaps in the consumer’s level of knowledge about all the requirements for organic standards. The findings provide valuable input into the literature on what motivates organic consumption decisions. Implications for marketing, educational campaigns and food labelling are discussed.

Keywords: Organic consumption, demographics, organic labels, certification, political consumerism.

RESUMO

O mercado de alimentos orgânicos é um dos setores de alimentos que mais cresce na Austrália, com uma taxa média de 50% de crescimento no mercado nacional de 2008 a 2010 (Relatório do Mercado Orgânico da Austrália, 2010). Este trabalho concentra-se em identificar as características demográficas dos compradores de alimentos orgânicos, os fatores motivacionais que impulsionam a compra de alimentos orgânicos e o papel da cidadania política nas escolhas alimentares. O artigo conclui que o comprador de alimentos orgânicos é geralmente do sexo feminino e bem-educado, mas a idade, renda e presença de crianças no agregado familiar não são traços distintivos. O estudo sugere que o consumerismo político pode ser uma força motriz para o consumo de alimentos orgânicos, que foi expressa na desconfiança das empresas; na falta de fé no governo; em preocupações mais amplas sobre os padrões de uso da terra agrícola no contexto da sustentabilidade e na tendência de envolvimento em boicotes e assinatura de petições. Variáveis como gosto, frescura do produto e bem-estar animal foram fatores motivadores importantes. Enquanto os consumidores têm conhecimento suficiente para distinguir entre alimentos produzidos de forma convencional e alimentos cultivados organicamente, existem lacunas no nível de conhecimento sobre todos os requisitos para padrões orgânicos do consumidor. Os resultados fornecem um valioso contributo para a literatura sobre o que motiva as decisões de consumo de produtos orgânicos. São discutidas também as implicações para o marketing, campanhas educativas e de rotulagem de alimentos.

Palavras-chave: Consumo de produtos orgânicos, demografia, rotulagem orgânica, certificação, consumerismo político.

1. Introduction

Consumer demand for organic food has exploded in recent years. The Australian organic industry at this point commands a relatively small percentage of total market value (around 1%) but it represents significant opportunity as an expanding market. According to the Australian Organic Market Report (2010), authored by Kristiansen, Mitchell, Bez, & Monk (2010), more than 60% of Australian households now buy organic on occasions. Organic domestic retail sales have grown over 50% in two years. According to the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, organic farming is experiencing rapid growth of 10-30% a year, depending on the sector. It has a farm-gate value of $90 million, exports are estimated to be $40 million and the domestic retail market is valued at $250 million (Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, 2011). Due to the sheer geographical mass of Australia and different climates, Australia has a competitive advantage over other countries (particularly in production of fruit). Queensland is the leading state (with 7,103,189 million hectares in cultivation) and most of the certified agricultural land is used for extensive grazing such as beef production (Kristiansen et al., 2010). Australia has the largest area of certified organic land in the world, with 12 million hectares in cultivation compared to 1.9 million in the US (Willer & Kilcher, 2012). Organic farming is production without using synthetic chemicals or genetically modified organisms or products. Animal welfare, being central to organic farming, stipulates that living conditions must consider the natural needs of the animals for free movement, social behaviour, food, water, shade and sunlight (Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, 2011). Similar to the conventional produce sector, growing consumer demand for convenience foods has grown, such as ready meals, pre-cut vegetables and bagged salads. In turn, more packaged and branded products are now available. As a result of the upsurge in consumer demand, many food retail outlets, including conventional supermarkets, have added organic fruits and vegetables to their shelves; they now offer many organic produce items year-round increasing consumer access to organic produce.

This research has two research objectives: (1) which demographic characteristics influence the individuals buying organic food and (2) what are the motivations behind the decision to buy organic food?

2. Literature review

As the organic market grows, some natural questions arise: who is buying organic food and why are they turning to alternative food systems? Gaining insight into this issue is more than just an academic exercise as retailers and members of the organic industry (for example, farmers, processors, distributors, restaurant owners) can increase their profits by understanding who buys their products.

Studies into who buys organic food highlight demographic variables like gender, age, income, education and presence of children in the household. A common finding in studies on the organic food market is that purchasers are like to be young, highly educated and on relatively high incomes (Govindasamy & Italia, 1999). While many studies provide insight into consumer demographics, the results are conflicting and fail to paint a consistent picture of the “typical” organic consumer. Education is one of the few demographic variables to be consistently associated with organic or local food purchase. Zepeda and Deal (2009) suggest that education is a measure of one’s level of knowledge and information-seeking behaviour; indeed, scholars refer to the rise of the ‘reflexive’ consumer (Moore, 2008) as consumers actively seek information from the Internet, books and magazines and the mass media. Lockie, Lyons, Lawrence and Mummery (2002) found that the relationship between income and consumption was not strong as consumers take non-price attributes into account such as shelf-life, family acceptance, quality and usage or the avoidance of waste.

In the food marketing, there is a general consensus in the literature on the reasons why people buy organic food and the main reasons are product taste, personal health, product quality and concern about the degradation of the natural environment (Baker, Thompson, & Engelken, 2004; Didier and Sirieix, 2008; Hill & Lynchehaun, 2002; Honkanen, Verplanken, & Olsen, 2006; Lyons, 2006; McEachern & McClean, 2002; Pearson, Henryks, & Jones, 2010; Torjusen, Lieblein, Wandel, & Francis, 2001). The motivations behind food choices are many and varied. Consumer decision-making often evokes contradictions between values and trade-offs (Bingen, Sage, & Sirieix, 2011; Lockie, 2002; Zanoli & Naspetti, 2002). For instance, the consumption of seasonal and domestic vegetables has environmental benefits but consumers also value the variety and year-round choice that imported products provide (Chambers, Lobb, Butler, Harvey, & Traill, 2007). Meat and dairy products have high environmental impact (Tobler, Visschers, & Siegrist, 2011) but they are staple items for many consumers. These contradictions are briefly summarised here:

· Caring (demonstrated through cooking for the family, buying in-season produce, supporting smaller retailers and producers in farmers’ markets) and convenience (provided by ready-to-eat meals, buying at a one-stop shop such as a supermarket, seeking product variety and year-round availability that imported foods provide)

· Healthiness and hedonism

· Cost and quality

· Naturalness and industrialisation of organic food production

In the face of these contradictions, consumer behaviour is complex and highly variable. Most organic consumers are “switchers”, in the sense that they switch between organic and conventional foods (Pearson et al., 2010: 175). Researchers have identified a gap between consumer attitudes and behaviour: consumers who hold positive attitudes towards organic food exhibit a relatively low level of actual purchases (Padel & Foster, 2005). The general consensus in the literature is that situational forces are a powerful constraint on behaviour, with higher prices and limited availability being barriers to purchase (Pearson et al., 2010). Despite the vigour of this interest in consumers, there are gaps in the scope and direction of the work. Researchers conclude that “consumer research remains a fertile area for further investigation as researchers grapple with its inherent complexity (Pearson et al., 2010: 175).

Lacking from previous studies is the explicit link between demand for organic food and political consumerism. It has been argued that although conventional forms of civic engagement are losing ground, particularly in the US (Putnam, 1995), but also in western democracies, there has been a rise in looser and less hierarchical, informal networks (Stolle, Hooghe, & Micheletti, 2005). It is argued that behaviour such as the signing of email petitions, participation in informal local groups, culture jamming (use of humor and symbolic images from corporate world to break corporate power), the spontaneous organisation of rallies and protests, the buying or boycotting of products for political and ethical reasons are all forms of political citizenship. Furthermore, while traditional forms of participation ( simply registering, voting or holding party membership) have been declining, non-traditional forms are increasing due to the rise of new media and informal networks that help build political consciousness (Dubuisson-Quellier, Lamine, & le Velly, 2011; Stolle et al., 2005). By including measures of political consumerism in this survey, the study contributes to the current body of literature on Australian organic food.

Several scholars have explored the role of ethical dimensions in the purchase of organic food products (Guido, Prete, Peluso, Maloumby-Baka, & Buffa, 2010; Parker, Manstead, & Stradling, 1995). Moral norms have an influence on purchase intentions (Guido et al., 2010), which refers to a system of “internalised ethical rules” (Shaw, Shiu, & Clarke, 2000: 882) or personal beliefs regarding what is right or wrong (Parker et al., 1995). Moral norms play an important role in low-involvement situations such as food consumption (Goldsmith, Frieden, & Henderson, 1997). Researchers have linked moral attitudes, namely the positive, self-rewarding feeling of doing the right thing, to the consumption of organic food (Arvola et al., 2008).

It is proposed that the theory of planned behaviour, including attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control, is a valuable tool to explain the purchase behaviour in the organic food sector (Guido et al., 2010). The ‘theory of planned behaviour’ (Ajzen, 1991) is a predictive model of deliberate behaviours. It assumes that intention – an individual’s motivation to engage in a specific action – (e.g. to purchase organic food) is the best predictor of the actual behaviour. The TPB hypothesizes that intention is a result of three main determinants: attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control: (i) Attitude towards the behaviour, that is, the subjective positive or negative predisposition toward the target behaviour; (ii) subjective norm, which refers to the perception of social pressure to perform (or not) a specific behaviour; in other words, important others such as family and friends might approve or disapprove of the purchase of such products and (iii) perceived behavioural control, which concerns the perception of external factors that could facilitate (or hinder) the considered behaviour. In the context of organic foods, factors such as premium price and lack of availability in retail stores act as barriers to purchase (Guido et al., 2010). This research drew on the three key elements of this model, but did not actually test this conceptual model due to the small size of the sample.

3. Methodolgy

A computer-assisted questionnaire was developed which contained a section designed to elicit socio-demographic information; factors influencing food choices; sources of information search with respect to food; familiarity with organic food labels and their requirements, consumer attitudes towards food. In order to assess consumer attitudes towards food, individuals had to give their opinion on 8 statements about critical aspects of food consumption such as environmental and ethical aspects of food production. The final question related to capturing elements of the theory of planned behaviour. It measured consumer attitudes by using a seven-point Likert scale. Attitude was measured by the following behavioural beliefs: ‘I follow a healthy and balanced diet’ and ‘I eat natural products’, ‘I am willing to pay a high price for quality food.’. Subjective norms were determined by considering the following normative belief: ‘The approval of my partner or family is important to me when buying food.’ Perceived behavioural control was evaluated by means of the following control beliefs: ‘There is good variety of organic food in organic shops’, ‘Shops selling organic are easy to reach’ and ‘Shop prices of organic food are low’, ‘There is a good variety of organic food in the major supermarkets (Coles, Woolworths)’. Moral norms were measured through the following salient beliefs: ‘I feel obliged to buy organic food to protect my health’ and ‘I feel obliged to buy organic food to protect the health of my family.’ Purchase intention was measured by means of one statement: ‘I am likely to buy organic food in the next two weeks.’

Respondents were recruited from a local food network, an organic supermarket and a specialized organic store. Only consumers who had an interest in locally-grown and organic foods were asked to participate in the survey. The vast majority were committed organic food buyers with 130 respondents indicating that they were likely to buy organic food in the next two weeks. A total of 139 surveys were fully completed out of 153 attempted surveys.

4. Main results

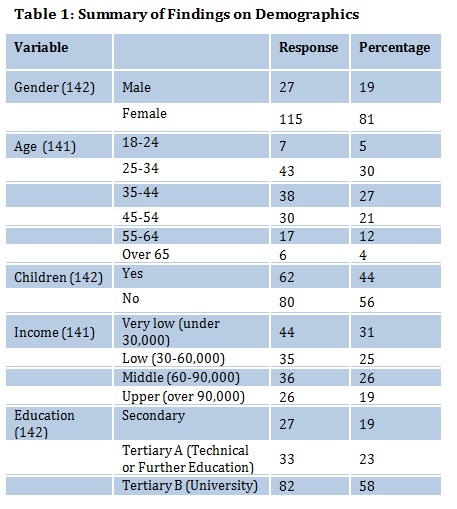

The following section reports demographic information, gender, education level, age, income and presence of children in the household. Table 1 outlines findings.

There were far more female respondents (81%) than males in the sample, showing, perhaps, that females make the majority of grocery purchases. There was a good range of ages in the sample. Almost a third of respondents were in the 25-34 category (30%) and less than a third (27%) were aged 35-44 and about one fifth (21%) of the sample were aged 45-54. Approximately half (56%) of the sample had no children living in the household.

Income was reclassified into four categories: very low, low, middle and upper incomes. Low incomes included all households with incomes below $30,000, middle incomes were households between $30,000 and $70,000, and upper incomes were households with incomes greater than $90,000 a year. In contrast to some studies that link income with organic food consumption, this sample was skewed towards individuals on very low (31%), low (25%) and middle (26%) incomes. Respondents were relatively well educated, with over half (58%) having a university degree, roughly one fifth (19%) with secondary level qualification and one fifth (23%) having a technical qualification.

4.1 level of organic and local food consumption, food outlets frequented, main sources of information used and factors governing food choices

One question sought to determine the percentage of the individual’s diet that consisted of organic food. The average value was 40% (138 responses). The analysis is organized around the concept that the decision to buy organic food occurs in two stages. A consumer first chooses whether to purchase organic food. Once he/she decides to buy organic, then he/she decides how much to buy, or how committed he/she should be to such purchases. Another question related to consumption of locally-grown food and the average value was 34%.

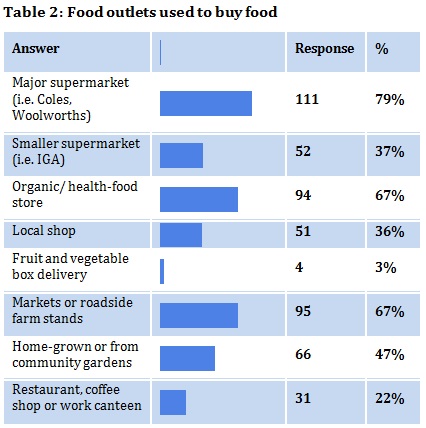

Table 2 shows that a variety of outlets were used by the sample, with most individuals (79%) buying food from major supermarkets and a high percentage using organic/health food stores (67%) and markets/roadside farm stands (67%). Almost half of the sample (47%) used home-grown produce or produce from community gardens.

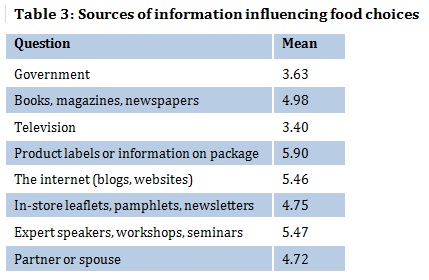

The most important sources of information governing food choices were product labels, followed by the internet, and expert speakers, workshops and seminars (see Table 3). This has strategic implications for packaging. Television and the government were not ranked as an important source of information. The fact that 68% of the sample (87 out of 127) see in-store leaflets, pamphlets, newsletters as somewhat important to very important has implications for retailers. Personal sources of information, partner or spouse, were rated as somewhat important to very important by 61% of respondents.

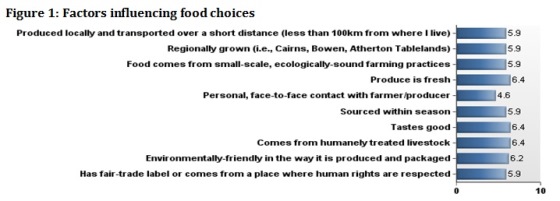

One question centred on the factors that influence food choices, showed in Figure 1. A 7 point scale ranging from ‘not at all important’ to ‘extremely important’ was used. Product attributes were critical and the top three factors (6.4) were as follows: produce is fresh; tastes good; comes from humanely treated livestock. In their food consumption choices, respondents took the wellbeing of animals, society and the environment into account.

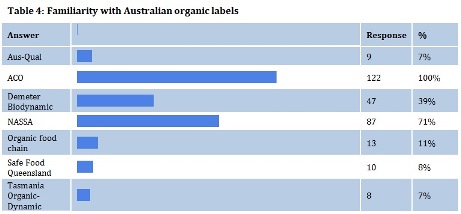

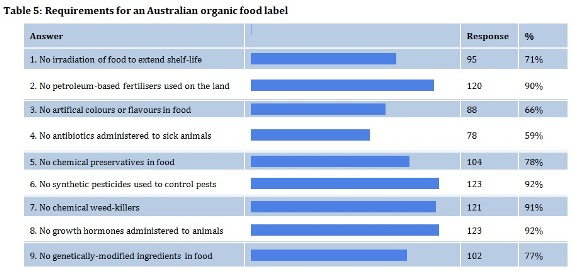

4.2 familiarity with organic food labels and requirements

A total of 122 respondents indicated familiarity with one organic food label, Australian Certified Organic, and 87 respondents were familiar with the NASSA label – see Table 4. The low level of recognition for other labels is not surprising given that they are either not available, or not actively marketed, in the state of Queensland. Most respondents correctly associate organic food with no artifical fertilisers and pesticides, chemicals and growth hormones. However, there is a low level of awareness of the other five requirements for organic food levels. Table 5 lists 9 requirements (no irradiation, no genetically modified ingredients etc) and no respondent ticked all boxes.

4.3 consumer behaviour: motivations for purchasing organic food, drivers and barriers towards purchase

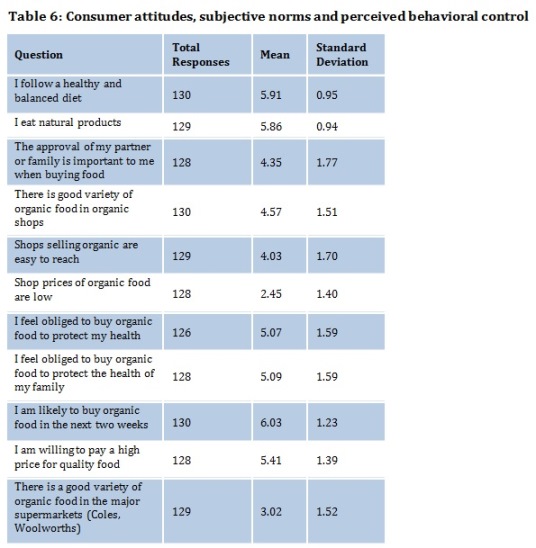

One section of the questionnaire was aimed at measuring consumer attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control by using a seven-point Likert scale. The responses are shown in Table 6. Consumer attitudes were positive with most agreeing with the statement: ‘I follow a healthy and balanced diet’ and ‘I eat natural products’, but respondents somewhat agreed with the statement, ‘I am willing to pay a high price for quality food’.

Social pressure (subjective norms) was determined by considering the following normative belief: ‘The approval of my partner or family is important to me when buying food.’ With a mean of 4.35, organic food purchase was not motivated by perceived subjective norms, or views of important others.

Perceived behavioural control was evaluated by means of the following control beliefs: ‘There is good variety of organic food in organic shops’, ‘Shops selling organic are easy to reach’ and ‘Shop prices of organic food are low’, ‘There is a good variety of organic food in the major supermarkets (Coles, Woolworths)’. Findings indicate that barriers to the purchase of organic food exist, such as price and lack of variety in supermarkets. Only 3 consumers (out of 128) agreed that shop prices of organic food are low.

Moral norms were measured through the following salient beliefs: ‘I feel obliged to buy organic food to protect my health’ and ‘I feel obliged to buy organic food to protect the health of my family.’ With a mean of 5, respondents somewhat agreed with these statements, thus moral obligation played some role in the decision to purchase organic food, but it was not crucial (did not get strong agreement).

Purchase intention was strong (measured by means of one statement: ‘I am likely to buy organic food in the next two weeks’) with 130 respondents in agreement.

4.4 consumer trust and political activism

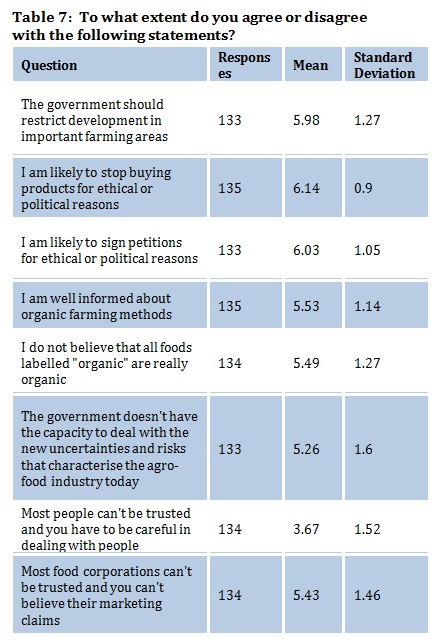

The last section of the questionnaire was designed to elicit information on people’s level of trust and degree of activism (See Table 7).

The majority of respondents believed that the government should restrict development in important farming areas and most (71%) somewhat to strongly agreed that the government doesn't have the capacity to deal with the new uncertainties and risks that characterise the agro-food industry today. The respondents appeared to activists who exhibited a strong tendency to stop buying products for ethical or political reasons and were likely to sign petitions for ethical or political reasons.

The majority of respondents were sceptical about the marketing claims of food corporations and didn’t believe that all food, labelled ‘organic’ was in fact organic. This has strategic implications for food manufacturers and for advertising campaigns, which will be discussed later.

The majority felt they were well informed about organic farming methods, although they seemed to have difficulty identifying all nine characteristics of organically certified food in an earlier question.

Interpersonal trust or generalised trust was measured by the statement ‘Most people can't be trusted and you have to be careful in dealing with people’ and only a third (34%) indicated agreement (somewhat agree to strongly agree) with this statement. Trust in corporations was, not surprisingly, low, with the majority (78%) agreeing with this statement.

5. Conclusions

Females featured predominantly in this study of organic buyers. Researchers take a gendered perspective in studies of food consumption and argue that gender identity is fundamental to food choices. The role of women in the food system is emphasised as they tend to be responsible for food preparation and food shopping. Furthermore, social pressures around healthy eating and bodily fitness, particularly in relation to children’s eating patterns, are relevant (Little, Ilbery, & Watts, 2009).

In their food consumption choices, respondents took product attributes such as freshness into account, as well as health, the wellbeing of animals, society and the environment, which is in line with previous studies (Baker et al., 2004; Didier & Sirieix, 2008; Hill & Lynchehaun, 2002; Honkanen et al., 2006; Lyons, 2006; McEachern & McClean, 2002; Pearson et al., 2010; Torjusen et al., 2001). In Australia, it could be said that anxiety over animal welfare has been propelled by the media. The suspension by the Australian government on live- cattle exports to Indonesia in 2011 was said to increase sales of organic meats as consumers sought ethical options (Organic Monitor, 2011). In making food choices, the respondents were influenced by a wide range of factors: whether the food was produced locally or regionally; coming from small-scale ecologically sound farming practices; sourced within season, environmentally friendly and carrying the fair-trade label. A concern for moral issues was evident in the findings. Price is an important issue, and this is validated in other studies. Although organic food is more expensive than conventional food due to greater labour intensity, poorer economies of scale, higher marketing costs and inefficiencies in the distribution chain, premium prices act as a barrier to purchase (Guido et al., 2010; Pearson et al., 2010).

An important step in promoting organic foods is to determine consumers’ understanding and knowledge of organic farming methods and the organic philosophy. While consumers have enough knowledge to distinguish between conventionally-grown food and organically-grown foods, there are gaps in the consumer’s level of knowledge about requirements for organic standards. Furthermore, the majority of consumers are aware of only two labels, despite the proliferation of organic standards in the Australian market. Scholars suggest that for consumers, this multitude of labels may be confusing rather than helpful in their efforts to identify organic foods. As the major standard bodies, retailers and producers don’t actively promote these labels, consumers may not able to recall them (Henryks and Pearson, 2010).

The study also examined the key sources of information used in the purchasing decision, with product labels, the internet and expert speakers, being key sources of knowledge. There was a relatively low ranking given to personal sources of information (partner or spouse). Although personal sources are trustworthy, they lack expertise (Quester, Neal, & Pettigrew, 2007). This has implications for marketing, educational campaigns and food labelling campaigns. Future campaigns should stress expert opinion, use rational appeals and be informative in nature. A recent survey found that familiarity with organic products is an important variable for marketers as organic is a relatively new term and consumer experience with organic produce is low. Thus marketers should strive to increase familiarity with organic produce by promoting trial and conducting education campaigns (Smith & Paladino, 2010). Organic foods are ‘credence goods’ because merely observing the food item does not inform the consumer about how their ingredients and how they were produced (Gifford & Bernard, 2011). However, packaged food items contain information about the product on the packaging and carry an organic label or seal. The relevance of credence attributes “underlines the considerable role played by certification and labelling aimed at reinforcing consumers’ confidence in organic food’ (Guido et al., 2010: 99). BildrgArd (2009) argues that certification schemes help maintain people’s trust in food in modern society.

This study paints a picture of organic food consumers as political consumers in line with the findings of Stolle et al. (2005). They are inclined to sign petitions and boycott products for political or ethical reasons. While political consumers tend to have trust in other citizens, they have less trust in established institutions (Stolle et al., 2005). This study found that organic food consumers exhibit a distrust of food corporations and their marketing claims. They don’t believe that all food labelled organic is, in fact, organic. The government, as one potential source of information on food, is not taken into consideration in their food choices. The majority don’t believe that the government has the capacity to deal with the new uncertainties and risks that characterise the agro-food industry today. This study, being quantitative in nature, did not probe respondents and didn’t explore why this mistrust has arisen. The fact that almost half of the sample used home-grown produce or produce from community gardens suggests that they exploited local food networks and were interested in where their food came from and the cost of this produce. There has been a proliferation of articles on alternative food networks or civic agriculture in the literature (Lyson & Guptill, 2004), particularly in the field of rural geography and agricultural economics. The localisation of food production and consumption has several potential benefits: the reduction of environmental impacts through shorter transportation distances, less exploitation of human labour and an increased sense of community through local networks of producers and consumers (Palovita, 2010). Alternative networks, such as box delivery schemes, invite scrutiny of agricultural production and help consumers learn about the variability of production, crop failure, pests and so on., as well as building citizenship and political consciousness (Dubuisson-Quellier et al., 2011).

There is a body of literature that argues that modern society has created widespread societal risk as well as heightened individual awareness of risks (Beck, 1992; BildtgArd, 2008; Giddens, 1991; Hutton & Giddens, 2000; Putnam, 1995). Beck’s (1992) Risk Society reports an emergence of individualism and general weakening of personal and family networks in society as a whole. The result is that individuals assume more responsibility for their individual biographies and have more freedom over life choices such as education, profession, place of residence and so on. Giddens (1990) suggests that in modern societies trust is based on reflexive thinking, where individuals weigh different values and different bodies of knowledge, scientific and traditional, economic and environmental, against each other. Scholars note that, as the organic food market becomes more main-stream and with products increasingly produced in a more industrialised way, it can worry consumers and leave them with doubts and questions as to whether organic food is really healthy (Berlin, Lockeretz, & Bell, 2009; Kristallis & Chryssohoidis, 2005). Organic products and production methods have been criticised by the media and scientific agencies, which creates confusion among potential consumers and ambivalence about whether or not choosing organic foods might lead to significant environmental and health outcomes (Lockie et al., 2002). With the mainstreaming of the sector, there has been considerable debate over the extent to which organic principles are compromised by large-scale and industrialised production methods, highly processed and nutritionally suspect organic foods and the energy-expensive transport of organic produce to export markets (Lockie, Lyons, & Lawrence, 2000; Rigby & Brown, 2007). Russell and Zepada (2008) have argued that food consumption behaviour is shifting from the organic to the local due to the commercialisation and industrialisation of the organic sector.

Some scholars argue that a somewhat simplistic view of the political consumer is taken in the literature and more qualitative research is required into the green consumer’s thoughts, reflections and ambivalences about food (Bostrom & Klintman, 2009; Connolly & Prothero, 2008). In the consumer behaviour field, Thompson (2011) has called for more extensive interdisciplinary research into the concept of the citizen-consumer in a politicized marketplace. Therefore, the organic food sector remains a fertile ground for investigation of concepts such trust, risk, the consumer-citizen, the level and forms of civic engagement. So far the examination has tended to focus on health, quality, and price and while not denying the relevance of such issues, this article argues that there are other influences that need to be incorporated into the model. For instance, a network perspective, combined with political consumerism, allows the author to look beyond the accepted motivations for buying organic and local foods. Do networks have the capacity to alter consumers’ choices? Will they mobilise consumers to become ‘regular’ organic consumers? Will they accelerate the shift from organic to local? Will consumers change their shopping patterns, will they move away from ‘one-stop shopping’ and source food from farmers’ markets, community gardens, etc. An investigation into the role of social networks in consumer decision-making process is particularly important given recent debates on social network and social capital theories (Castells, 1996; Granovetter, 1973).

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organisational Behaviour Human Decision Process, 50, 179-211. [ Links ]

Arvola, A., Vassallo, M., Dean, M., Lampil, P., Saba, A., Lahteenmaaki, L. et al. (2008). Predicting intentions to purchase organic food: the role of affective and moral attitudes in the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite, 50, 443-454. [ Links ]

Baker, S., Thompson, K. E. & Engelken, J. (2004). Mapping the values driving organic food choice. European Journal of Marketing, 38, 995-1012. [ Links ]

Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Berlin, L., Lockeretz, W. & Bell, R. (2009). Purchasing foods produced on organic, small and local farms: a mixed method analysis of New England consumers. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 24, 267-275. [ Links ]

BildtgArd, T. (2008). Trust in food in modern and late-modern societies. Social Science Information sur les sciences sociales, 47 (1), 99-128. [ Links ]

Bingen, J., Sage, J. & Sirieix, L. (2011). Consumer coping strategies: a study of consumers committed to eating local. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 35, 410-419. [ Links ]

Bostrom, M., & Klintman, M. (2009). The green political consumer: a critical analysis of the research and policies. Anthropology of Food, S5, 1-14.

Castells, M. (1996). The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [ Links ]

Chambers, S., Lobb, A., Butler, L., Harvey, K., & Traill, W. (2007). Local, national and imported foods: a qualitative study. Appetite, 49, 208-213. [ Links ]

Connolly, J., & Prothero, A. (2008). Green consumption: Life-politics, risk and contradictions. Journal of Consumer Culture, 8, 117-145. [ Links ]

DAFF Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. (2010). Australian Food Statistics 2009-10. Canberra: ACT. [ Links ]

Didier, T. & Sirieix, L. (2008). Measuring consumer’s willingness to pay for organic and fair trade products. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 32, 479-490. [ Links ]

Dubuisson-Quellier, S., Lamine, C., & le Velly, R. (2011). Citizenship and consumption: Mobilisation in alternative food systems in France’. Sociologia Ruralis, 51, 304-322. [ Links ]

Giddens, A. (1990). The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the late Modern Age. Cambridge: Policy Press. [ Links ]

Gifford, K., & Bernard, J. (2011). The effect of information on consumers willingness to pay for natural and organic chicken’. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 35, 282-289. [ Links ]

Gocindasamy, R., & Italia, J. (1999). Predicting willingness to pay for organically grown fresh produce. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 30 (2), 44-53. [ Links ]

Goldsmith, R., Frieden, J., & Henderson, K. (1997). The impact of social values on food-related attitudes. British Food Journal, 99, 352-357. [ Links ]

Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360-1380. [ Links ]

Guido, G., Prete, I., Peluso, A., Maloumby-Baka, C., & Buffa, C. (2010). The role of ethics and product personality in the intention to purchase organic food products: a structural equation modelling approach. International Review of Economics, 57, 79-102. [ Links ]

Henrykes, J., & Pearson, D. (2010). Misreading between the lines: Consumer confusion over organic food labelling. Australian Journal of Communication, 37 (3), 73-86. [ Links ]

Hill, H. & Lynchehaun, F. (2002). Organic milk: Attitudes and consumption patterns. British Food Journal, 104, 526-542. [ Links ]

Honkanen, P., Verplanken, B., & Olsen, S.O. (2006). Ethical values and motives driving organic food choice. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 5, 420-431. [ Links ]

Hutten, W., & Giddens, A. (2000). On the Edge: Living With Global Capitalism. London: Jonathan Cape. [ Links ]

Kristallis, A., & Chryssohoidis, G. (2005). Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic food: Factors that affect it and variation per organic product type. British Food Journal, 107, 320-343. [ Links ]

Kristiansen, P., Mitchell, A., Bez, N., & Monk, A. (2010). Australian Organic Market Report 2008. Biological Farmers of Australia, Brisbane. Retrieved March, 2012, from http://www.bfa.com.au/Portals/0/100824 Mediabrief-AOMR2010.pdf . [ Links ]

Little, J., Ilbery, B., & Watts, D. (2009). Gender, consumption and the relocalisation of food: A Research Agenda. Sociologia Ruralis, 49, 201–217. [ Links ]

Lockie, S. (2002). The invisible mouth: Mobilizing the consumer in food production-consumption networks. Sociologia Ruralis, 42, 278-294. [ Links ]

Lockie, S., Lyons, K. & Lawrence, G. (2000). Constructing ‘green’ foods; corporate capital, risk and organic farming in Australia and New Zealand. Agriculture and Human Values, 17, 315-322. [ Links ]

Lockie, S., Lyons, K., Lawrence, G., & Mummery, K. (2002). Eating ‘green’: motivations behind organic food consumption in Australia. Sociologia Ruralis, 42, 20-37. [ Links ]

Lyons, K. (2006). Environmental values and food choices: Views from Australian organic food consumers. Journal of Australian Studies, 87, 155-166. [ Links ]

Lyson, T. & Guptill, A. (2004). Commodity agriculture, civic agriculture and the future of U.S. farming. Sociologia ruralis, 69, 370-385. [ Links ]

McEachern, M.G. & McClean, P. (2002). Organic purchasing motivations and attitudes: Are they ethical?. International Journal of Consumer Studies , 26, 85-92. [ Links ]

Moore, O. (2008). How embedded are organic fresh fruit and vegetables at Irish farmer’s markets and what does the answer say about the organic movement? An exploration, using three models’. International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology, 7, 144-157. [ Links ]

Organic Monitor. (2011). Australia: ethical consumerism increasing organic meat sales. Retrieved August 23, 2011, from http://www.organicmonitor.com/oceania.htm [ Links ]

Padel, S. & Foster, C. (2005). Exploring the gap between attitudes and behaviour: Understanding why consumers buy or do not buy organic food. British Food Journal, 107, 606-626. [ Links ]

Palovita, A. (2010). Consumers’ sustainability perceptions of the supply chain of locally produced food. Sustainability, 2, 1492-1509. [ Links ]

Parker, D., Manstead, A., & Stradling, S., (1995). Extending the theory of planned behaviour: the role of personal norm. British Journal of Social Psychology, 34, 127-137. [ Links ]

Pearson, D., Henryks, J. & Jones, H. (2010). Organic food: What we know (and do not know) about consumers. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 26, 171-177. [ Links ]

Putnam, R. (1995). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster. [ Links ]

Quester, P., Neal, C., & Pettigrew, S. (2007). Consumer Behaviour: Implications for Marketing Strategy (5th ed.). North Ride, New South Wales: McGraw-Hill-Irwin. [ Links ]

Rigby, D. & Brown, S. (2007). Whatever happened to organic? food, nature and the market for “sustainable” food. Capitalism Nature Socialism,18 (3), 81-102. [ Links ]

Russell, W., & Zepeda, L. (2008). The adaptive consumer: shifting attitudes, behaviour change and CSA membership renewal. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 23, 136-148. [ Links ]

Shaw, D., Shiu, E., & Clarke, I. (2000). The contribution of ethical obligation and self identity to the theory of planned behaviour: an exploration of ethical consumers. Journal of Marketing Management, 16, 879-894. [ Links ]

Smith, S., & Paladino, A. (2010). Eating clean and green? Investigating consumer motivations towards the purchase of organic food. Australasian Marketing Journal, 18, 93-104. [ Links ]

Stolle, D., Hooghe, M., & Micheletti, M. (2005). Politics in the supermarket: Political consumerism as a form of political participation. International Political Science Review, 26, 245-269. [ Links ]

Thompson, C. (2011). Understanding consumption as political and moral practice: introduction to special issue. Journal of Consumer Culture, 11, 139-144. [ Links ]

Tobler, C., Visschers, V. & Siegrist, M. (2011). Organic tomatoes versus canned beans: how do consumers assess the environmental friendliness of vegetables?. Environment and behaviour, XX(X) 1–21, retrieved from http://www.scp-knowledge.eu/sites/default/files/knowledge/attachments/Tobleretal_OrganicTomatoesVersusCannedBeans_EaB_2011.pdf. [ Links ] .

Torjusen, H., Lieblein, G., Wandel, M., & Francis, C.A. (2001). Food system orientation and quality perception among consumers and producers of organic food in Hedmark County, Norway. Food Quality and Preference, 12, 207-216. [ Links ]

Willer, H. & Kilcher, L. (2012). The World of Organic Agriculture - Statistics and Emerging Trends 2012. Retrieved June, 2012, from http://www.organic-world.net/1690.html. [ Links ]

Zanoli, R., & Naspetti, S. (2002). Consumer motivations in the purchase of organic food: A means-end approach. British Food Journal, 104, 643-653. [ Links ]

Zepeda, L., Deal, D. (2009). Organic and local food consumer behaviour: Alphabet theory. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33, 697-705. [ Links ]

Article history

Submitted: 23 June 2012

Accepted: 14 October 2012