Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Tourism & Management Studies

Print version ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.12 no.1 Faro Mar. 2016

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2016.12102

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Hotel Assessment through Social Media: The case of TripAdvisor

La valoración de los hoteles en los medios sociales: El caso de TripAdvisor

Sebastian Molinillo1, José Luis Ximénez-de-Sandoval2, Antonio Fernández-Morales3, Andres Coca-Stefaniak4

1University of Malaga, Faculty of Economics and Business, Department of Business Management, Campus El Ejido, 29013 Malaga, Spain. E-mail: smolinillo@uma.es

2University of Malaga, Faculty of Tourism, Campus Teatinos, Malaga, Spain. E-mail: joseluis.xs@uma.es

3University of Malaga, Faculty of Economics and Business, Department of Applied Economics, Campus El Ejido, 29013 Malaga, Spain. E-mail: afdez@uma.es

4University of Greenwich, Business School, Department of Marketing, Events and Tourism, Old Royal Naval College, Park Row, London SE10 9LS, United Kingdom. E-mail: a.coca-stefaniak@gre.ac.uk

ABSTRACT

Hotel booking decisions are increasingly influenced by consumer feedback available on social media sites. Using data submitted by customers on TripAdvisor, this study analyzes the customer satisfaction ratings posted for 2,211 hotels. The study provides four key contributions to our knowledge on this subject. Firstly, a comparative analysis was conducted of customer ratings for hotels located on the Spanish coast and Portugals southern coast. Secondly, significant differences were found in the number of comments and average online review ratings, which showed a correlation to the tourism destinations geographical locations. Thirdly, the study found that customers tend to rate their hotel experiences positively. Fourthly, the customers overall level of satisfaction with a hotel tends to increase proportionately based on the number of customer feedback comments posted for that hotel. Consequently, one of this studys findings is that hotels should encourage their customers to post comments on customer review websites to balance out any negative feedback.

Keywords: Consumer review websites, hotel, electronic word of mouth, eWOM, TripAdvisor.

RESUMEN

La decisión de contratar los servicios de un establecimiento hotelero está cada vez más influenciada por los comentarios online de los consumidores. A partir de las valoraciones emitidas por los usuarios de TripAdvisor, esta investigación analiza los índices de satisfacción de los clientes de 2.211 hoteles. El estudio realiza cuatro contribuciones principales. Primero, se muestra un análisis comparado de las puntuaciones de los hoteles situados en las zonas turísticas de la costa de España y del sur de Portugal. Segundo, se observan diferencias significativas en el número de comentarios y en la puntuación global media obtenida en función de la zona turística. Tercero, se pone de manifiesto que los clientes suelen calificar positivamente sus experiencias en los hoteles. Cuarto, el valor de la satisfacción global de un hotel aumenta conforme lo hace el número de comentarios recibidos por habitación. Por lo tanto, una conclusión importante de este trabajo es que las empresas hoteleras deben animar a sus clientes para que realicen comentarios para contrarrestar el efecto de los comentarios negativos.

Palabras-clave: Comunidades online de viajeros, hotel, boca oído electrónico, TripAdvisor.

1. Introduction

Tourists use of social media, particularly the feedback, comments, views, and ratings posted online by hotel customers (e.g. TripAdvisor, Expedia, Yelp) has developed a growing influence on the decision-making processes of other potential visitors (Stringam & Gerdes, 2010; Leung, Law, Van Hoof, & Buhalis, 2013; Xie, Chen, & Wu, 2015). Moreover, research has shown that potential customers tend to trust written comments posted online by other customers more than recommendations found on official destination marketing or hotel websites (Sparks, Perkins, & Buckley, 2013).

Over the last decade, a growing number of authors have sought to gain a better understanding of consumer behavior on customer review websites as well as the strategies used by organizations to manage their presence online. However, many hotel managers still have a lack of confidence in the underlying motives behind negative online customer reviews (Levy, Duan, & Boo, 2013) and a certain degree of uncertainty as to whether customer social media feedback is dominated by negative customer service experiences. Furthermore, some hospitality professionals seem to believe that only larger organizations in this sector have the necessary resources to effectively manage their online presence (Hashim & Murphy, 2007).

The study examines this idea held by some hotel managers by analyzing the customer comments posted on one of the worlds most popular tourism customer review websites – TripAdvisor. The study expands on similar research carried out by OConnor (2010) in England, but rather focusing on seaside hotels in Spain and southern Portugal, which remain largely under-researched in the field of tourism social media, despite their economic and geographical relevance in the European tourism industry (Schuckert, Liu, & Law, 2015). This research makes numerous key contributions to hospitality management literature. Firstly, it provides an international comparative analysis of online ratings for hotels located in seaside tourist destinations in Spain and southern Portugal. Secondly, it shows significant differences between the number of comments and the overall mean hotel ratings from reviewers, depending on the destination. Thirdly, it found that most customers tend to value their hotel experiences positively. Fourthly, the results of this study indicate that hotels overall customer satisfaction ratings increase proportionally to the number of customer comments posted online.

This paper is structured in five sections. The first evaluates the importance of the development and use of online content regarding hotels on customer review websites. The following section discusses the role of TripAdvisor in the tourism sector in regards to the dissemination of customer reviews. The next section outlines the studys key research questions, followed by a summary of the research methodology and analysis of the collected data. The last section presents a critical discussion of the main findings with implications for hotel managers and further academic research.

2. Development and use of hotel service feedback through customer review websites

Customer review websites are becoming an increasingly important source of information for visitors (Xiang & Gretzel, 2010). More specifically, the feedback content posted online is changing the way consumers compare different products and services (Ghose, Ipeirotis, & Li, 2012). According to a recent global TripAdvisor (2013b) survey, holiday planning is becoming increasingly dominated by online resources and, particularly, customer review websites, with 69% of tourists going online to plan their holidays. This percentage is even higher in Spain at 83%.

Customers play a dual role on customer review websites. On the one hand, they can actively influence opinions by posting comments online, while on the other,, they may passively consume information posted by others in order to develop their own decision-making process. According to Yoo and Gretzel (2011), although over 50% of tourists consume online content generated by others, only a limited number of these website users actually provide their own online comments. The vast majority (70%) of consumer content generated by tourists in 2011 was posted on Online Travel Agency (OTA) websites, including Expedia and Booking, while the remaining 30% was posted on specific websites or customer review websites for visitors and tourists. Among the latter, TripAdvisor has made a considerable effort to encourage tourists to post their feedback online and has thereby become a leading provider of customer reviews in the hospitality sector in terms of number of posts and number of views. In 2011, the year-on-year growth of customer review posts on TripAdvisor was 69%, whereas the yearly change was only 37% for OTAs (Quinby & Rauch, 2012).

In order to establish an average profile of people that provide online reviews, a study by Bronner and De Hoog (2011) analyzed a sample of 3,500 Dutch tourists and concluded that the average profile was people under the age of 55, traveling with their spouse or partner, and with or without children. Their main motivating factors for posting a customer review included: (i) personal satisfaction, (ii) helping other tourists, (iii) social benefit, (iv) increasing customer power, and (v) helping service providers. According to Jurca, Garcin, Talwar, and Faltings (2010), online users are more motivated to post a review on TripAdvisor when they perceive a higher transaction risk. Furthermore, Liu, Schuckert, and Law (2015) found an effect on motivating reviews in TripAdvisor by awarding reviewers increasingly higher status on the platform; their results showed that the quality of the review drops as the reviewer's status increases, and reviewers with a higher status are less likely to publish extreme ratings. On the other hand, Yoo and Gretzel (2011) posit that personality is a key differentiating factor between people who post reviews online and those who do not. According to these authors, people who post reviews online tend to be more altruistic and hedonistic, whereas those who do not tend to be more self-centered and conscious of their time commitments. Serra Cantallops and Salvi (2014) provide a review of e-WOM literature in the hospitality sector, identifying the key variables governing earlier studies on the motivating factors behind online review posts, which until now had largely ignored the hotel as a variable. Nevertheless, Zhou, Ye, Pearce, and Wu (2014) considered certain hotel attributes linked to hotel size and capacity (e.g. reception, swimming pool, gym, etc.) in their study of customer satisfaction on customer review websites.

Gretzel (2007) showed that tourists tend to value other peoples online reviews as being more influential than any other tourism products in their decision-making process regarding hotel choice. In this sense, as suggested by Quinby and Rauch (2012), the travelers voice plays an increasingly important role in the search process for finding the right destination package. Along the same lines, 56.6% of tourists visiting Spain in 2010 used the Internet as part of their search process and 39% of these tourists used the web to learn more about accommodation options (Instituto de Estudios Turísticos, 2011).

Considering the actual intention to follow advice offered on customer review websites, a study by Casaló, Flavián, and Guinalíu (2011) found that at least three factors are involved, specifically: (i) those related to the nature of the advice provided (perceived usefulness of the advice), (ii) those related to the source of the advice (trust in the website offering the customer reviews) and (iii) those related to the personal characteristics of the tourist who has to decide whether to follow the advice or ignore it. Regarding perceived usefulness, Liu and Park (2015) showed that a combination of both messenger (i.e., personal identity disclosure, expertise and reputation) and message characteristics (i.e., star ratings, length, enjoyment and review readability) positively influence the usefulness of reviews. In addition, Park and Nicolau (2015) found that people perceive extreme ratings (positive or negative) as more useful and enjoyable than moderate ratings, and negative ratings as more useful than positive ones. Casaló, Flavián, Guinalíu, and Ekinci (2015) suggested that high risk-averse travelers find negative online reviews more useful than positive reviews. These travelers also think that well-known brand names, reviewers expertise and pictures enhance the usefulness of the positive reviews. Additionally, Luo, Luo, Xu, Warkentin, and Sia (2015) found that readers sense of belonging to virtual forums mitigates the effects of comment antecedent factors on their perceptions of review credibility.

Other studies have examined the influence of trip-related factors (e.g. familiarity with the chosen destination, its geographical location, travel distance, etc.) and even the relationship between tourists genders and the use of online customer reviews to plan a trip. Gender factors have indeed been found to influence behavior related to online reviews. In a survey of 2,830 U.S. hotel leisure and business customers, Verma, Stock, and McCarthy (2012) showed that women tend to be more prone to reading online reviews on TripAdvisor than men. In addition, the study found that employers recommendations were the dominant factor in terms of hotel choice for business travel, while the dominant factor for leisure travelers was generally recommendations from family and friends. Furthermore, Lee and Hyun (2015) found that social and emotional loneliness, with the moderating role of emotional expressivity, influence the intention to follow travel advice from online travel communities.

Given the importance and influence of online reviews on visitors decisions, there is growing concern about the possibility of people posting fake online reviews that may seem real in order to mislead customers (Ott, Choi, Cardie, & Hancock, 2011). Accordingly, Ott, Cardie, and Hancock (2012) used a model to explore the prevalence of fake positive reviews (no account was made for potentially fake negative reviews) on six well-known customer review websites: Expedia, Hotels.com, Orbitz, Priceline, TripAdvisor, and Yelp. The authors of this study concluded that sites where it is easier to post online reviews had a higher level of fake customer reviews than websites where it is more difficult to post said reviews. This study showed that sites such as Hotels.com contained an average of approximately 2% of fake customer reviews, whereas the percentage doubled to 4% for TripAdvisor. Nevertheless, Casaló, Flavián, and Guinalíu (2010) showed that developing rules to regulate participation in these customer review websites has a negative effect on content generation and further customer reviews. As a result, and along the lines of other studies (e.g. Melián-González, Bulchand-Gidumal, & López-Valcárcel, 2013), one way of reducing the influence of fake online reviews is to make it easier for more reviews to be posted through higher levels of participation, since larger numbers of reviews are usually associated with higher levels of credibility linked to the law of statistical averages, thus minimizing the influence of any fake customer reviews posted by hospitality businesses.

3. TripAdvisors role in the dissemination of online customer reviews

It is difficult to ignore TripAdvisors statistics for the dissemination of online reviews in terms of number of comments posted and website visits. Indeed, the website has grown considerably from 2006 to 2013. In July 2006, there were over 5 million comments posted on TripAdvisors website for 220,000 hotels and attractions. A few years later, in April 2013, there were over 100 million reviews from travelers all over the world, in addition to 2,500,000 posts from businesses, 700,000 of which were for hotels and over 116,000 for destinations (TripAdvisor, 2013a).

TripAdvisor is the most well-known customer review website for hotels and restaurants in Spain, although Yelp.com is more popular on a global scale. According to Alexa.com, in May 2013 TripAdvisor.com was ranked 233 among the most visited websites in the world behind Yelp.com (193), while in Spain, TripAdvisors ranking (137) was considerably ahead of Yelp (1,037).

TripAdvisor users can write reviews and post scores from 1 (terrible) to 5 (excellent) following a number of criteria including overall satisfaction, quality of sleep, location, rooms, service, price-quality ratio, and cleanliness. Xie et al. (2015) showed the effect of online consumer review factors on TripAdvisor (i.e. quality, quantity, consistency, and recency) on offline hotel occupancy. The hotels location influences its affordability (Lado-Sestayo, Otero-González, & Vivel-Búa, 2014) and, although this is an important factor affecting hotel choice, it tends to have little impact on overall customer satisfaction (Fernández-Barcala, González-Díaz, Prieto-Rodriguez, & Pestana-Barros, 2009; Jeong and Jeon, 2008; Limberger, dos Anjos, de Souza Meira, & dos Anjos, 2014). Nevertheless, a number of studies have investigated the impact of TripAdvisor on hotel locations. Cunningham, Smyth, Wu, and Greene (2010) compared the overall hotel offering in Ireland and Las Vegas (United States) and concluded that Irelands hotels improved their quality in order to avoid negative customer reviews on TripAdvisor. According to a study by Verma et al. (2012), when a potential customer finds negative reviews online, the probability of booking a room is approximately 40%, while positive customer reviews increase the probability to 70-80%. Anderson (2012) also found that the number of consumers who check reviews on TripAdvisor before booking a hotel has increased over time and that improvements in average hotel ratings may allow for higher prices to be charged per room while occupancy levels remain unchanged.

However, despite the positive effects of good online customer reviews, OConnors study of London hotels (2010) found that very few businesses actively manage their online reputation on TripAdvisor. Along these lines, Park and Allen (2013) studied the extent to which hotel directors manage online reviews of their establishments on TripAdvisor. They concluded that hoteliers who replied to online reviews saw these reviews as honest reflections of their customers feelings, whereas those who did not respond to online reviews saw these reviews as lacking balance and only reflecting extremes (positive and negative) within the spectrum. Moreover, according to López-Fernández, Serrano-Bedia, and Gómez-López (2011), there is a positive correlation between adopting innovation in the hotel industry and the size of the business. Tejada and Moreno (2013) go even further to point out that the best indicator for assessing a hotels level of innovation may be the establishments number of rooms.

The above raises, a number of questions regarding the number of online reviews and overall TripAdvisor hotel scores:

1. Does the number of online reviews vary depending on the tourism destination?

2. Are customers generally very critical of hotels during the satisfaction rating process?

3. Are there differences between the overall hotel ratings given by customers for different tourism destinations?

4. Is there a relationship between hotel size and the corresponding number of online customer reviews?

5. Is there a relationship between hotel size and the corresponding online customer ratings?

6. Is there a relationship between the number of online reviews for a hotel and its overall online customer ratings?

4. Methodology

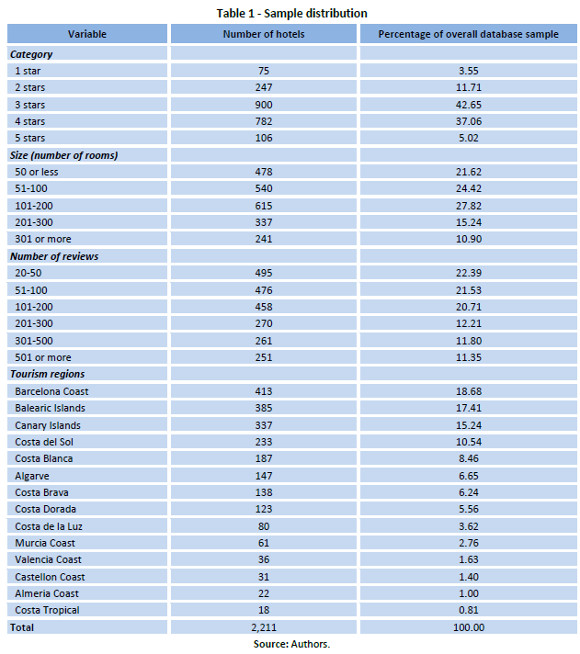

Web-based content research using customer reviews, opinions and comments has become widespread over the last decade or so (e.g. Jurca et al., 2010). For this study, a database was first developed using available hotel information on TripAdvisor.es for coastal destinations in Spain and southern Portugal. This information was extracted using an automated system and a database was developed with information on 3,202 hotels. However, considering earlier studies in this field (e.g. Chaves, Gomes, & Pedron, 2012), and in order to achieve a higher level of credibility for the data, all hotels with fewer than 20 online reviews were removed from the database. The final version of the database was therefore reduced to 2,211 hotels. Using a classification of tourism destination regions developed by the Spanish Governments Office for National Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística), fourteen geographical categories were created corresponding to different tourism regions, as shown in Table 1.

In order to provide answers to the aforementioned research questions, relationships between variables were scrutinized using analysis of variance (ANOVA), independent sample t-test and the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance non-parametric test to evaluate the results. All calculations were performed with STATA v12 and the level of significance chosen for contrasting the results was fixed at 5%.

5. Results

5.1 Number of online reviews by tourism destination region

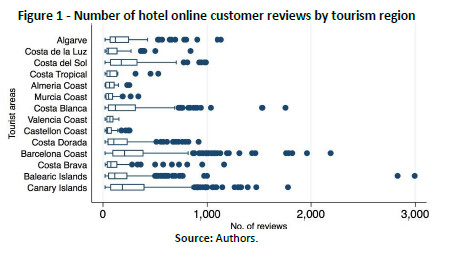

The analysis of online hotel customer reviews by tourism destination found that hotels located on the Barcelona Coast and in the Canary Islands received more online reviews on average (304 and 303 respectively), whereas those located in the Valencia Coast and Murcia Coast regions attracted the lowest number of online reviews (71.17 and 71.95 respectively). The Balearic Islands and Barcelona Coast feature some hotels with over 2,000 online reviews, while on the other side of the spectrum, some hotels on the Valencia Coast did not even receive more than 150 online reviews (see Figure 1).

5.2 Global average customer scores by tourism region

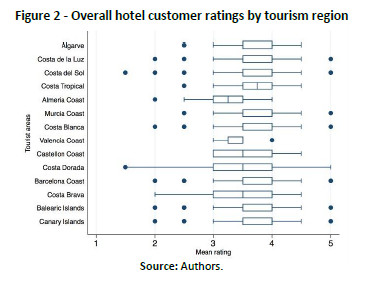

TripAdvisors online scoring allows customers to award quantitative scores ranging from 1 (terrible) to 5 (excellent). The average hotel score for the sample analyzed in this study was 3.72. None of the hotels in the sample had received an overall customer rating of 1 and only 4.98% of them had overall ratings ranging from 1.5 to 2.5, while 52.56% had overall ratings ranging from 4 to 5. Consequently, we can conclude that the majority of customers on TripAdvisor awarded scores that seem to reflect favorable experiences during their hotel stays in the geographic regions analyzed in this study.

If we take into account specific tourism destination regions, hotels on the Barcelona Coast tend to receive the highest scores (3.82), while the lowest scores correspond to hotels located on the Almería Coast (3.18). Evidence of the most divergent individual hotel ratings can be found on the Costa Dorada. The two regions with the lowest individual hotel ratings are the Costa del Sol and the Costa Dorada, with values reaching a minimum of 1.5 in each region. The Castellón Coast and the Valencia Coast have the highest minimum spot values as none of their hotels have been rated under 3. Nevertheless, the Valencia Coast and the Almería Coast also have the lowest maximum ratings, since none of their hotels have overall customer ratings over 4 (see Figure 2).

5.3 Analysis of the number of qualitative online customer reviews by hotel size

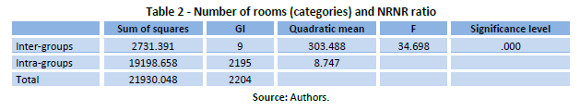

Generally, the number of customer reviews posted online tends to have a positive influence on the hotels credibility. This issue also affects customers decision-making processes and the hotels position in TripAdvisor customer rankings. However, it could be argued that the number of reviews posted online is related to the size of the hotel. For instance, customers will tend to award a higher level of credibility to 300 online reviews for a hotel with a capacity of 10 rooms than they would if the hotel had a capacity of 100 rooms. This study therefore proposes the development of a NRNR (Number of Reviews per Number of Rooms) ratio, which would be equal to the total number of online reviews divided by the hotels total room capacity. This ratio was used to develop ten different categories with the same number of hotels in each. Upon further analysis, the NRNR ratio was found to decrease in value as hotel size (number of rooms) increased. In other words, the number of qualitative online reviews per room decreases as the number of rooms (capacity) increases.

Three prerequisites must be met in order to carry out an analysis of variance: independence of observations, normality and homoscedasticity, i.e. homogeneity of variances. Homoscedasticity was tested using Levenes variance test, with a significance level of 0.000 <0.05, which resulted in the rejection of the null hypothesis (H0) for equality of variances. The analysis of variance for the variables number of rooms and average hotel online score [TripAdvisor] allowed H0 to be rejected (equal averages). As some average values were significantly different, this would suggest that there is a certain degree of relationship between a hotels number of rooms and its overall online review score. Using a significance level 0.05, the null hypothesis was rejected H0 = equal averages (see Table 2). Therefore, there was a significant difference among some of the average values, which would indicate a certain degree of relationship between a hotels number of rooms and the value of its NRNR ratio.

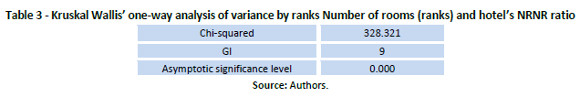

However, in order to complete the analysis of variance considering that the normality test was not carried out and homoscedasticity could not be demonstrated, Kruskal Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks was performed to confirm the results. The Kruskal-Wallis analysis was statistically significant at the 5% significance level (H0 rejected) (see Table 3). This supports the conclusion that there are statistically significant differences between the average levels and that, consequently, there is a certain degree of relationship between a hotels size and its NRNR ratio.

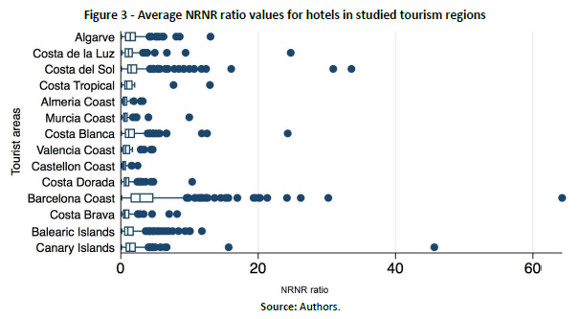

For the analysis by tourism regions, hotels located in Barcelonas coastal area seem to stand out over other destinations with numerous hotels boasting over 64 customers reviews per room. On the other end of the spectrum, hotels located on the Almería Coast, Castellón Coast and Valencia Coast appeared to have engaged fewer customers in terms of reviews posted on TripAdvisor (see Figure 3). The NRNR ratio is useful for evaluating differences in the number of online customer reviews compared to the hotel capacity of any given area or region. While the number of hotel reviews for the Canary Islands is similar to the Barcelona Coast, the use of the NRNR ratio reveals that, on average, more reviews are posted for hotels on the Barcelona coast if the size of these hotels is taken into account.

5.4 Analysis of the relationship between hotel size and its customer review score on TripAdvisor

The average size of the hotels in this studys database sample was approximately 150 rooms per hotel, although hotel capacity varies considerably since the sample contains hotels ranging from only 2 rooms to up to 1,468 rooms. In order to determine whether there is a relationship between the number of hotel rooms and overall customer review ratings on TripAdvisor, this study grouped hotels into 10 size intervals so that each interval included approximately 10% of the total number of hotels studied. The first interval included hotels with a capacity ranging from 1 to 30 rooms and the last interval included hotels with a capacity ranging from 313 to 1,468 rooms. The results of the analysis showed a statistically significant difference between the average online customer review scores for each interval, which indicates a certain degree of relationship between a hotels number of rooms and its average online review score. In fact, 75% of the hotels studied with maximum scores belonged to the smallest hotel category (hotels with a capacity of 1 to 30 rooms). There also seems to be a trend in customers reducing their online ratings for hotels up to a capacity of 111 rooms. Beyond that size, the trend was found to be erratic.

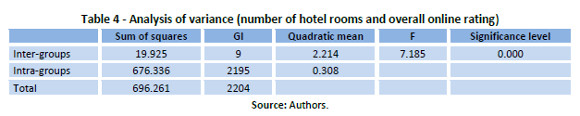

Similarly to the previous analysis summarized in section 5.3, homoscedasticity was tested using Levenes variance test, which resulted in a significance level of 0.350 >0.05 and, therefore, in the acceptance of the null hypothesis (H0) for equality of variances. The analysis of variance for the variables number of rooms and average hotel online score [TripAdvisor] allowed H0 to be rejected (equal averages) (Table 4). As some average values were significantly different, this would suggest that there is a certain degree of relationship between a hotels number of rooms and its overall online review score.

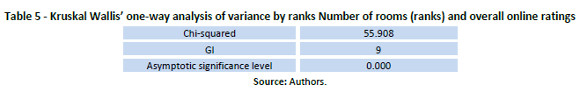

However, in order to complete the analysis of variance considering that the normality test was not carried out, Kruskal Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks was performed to confirm the results. The Kruskal-Wallis analysis was statistically significant at the 5% significance level (H0 rejected) (Table 5). This supports the conclusion that there are statistically significant differences between the average levels and that, consequently, there is a certain degree of relationship between a hotels size and its NRNR ratio.

Furthermore, if we consider hotels with overall ratings of 4.5 or higher, it is evident that as the size of hotels increases, the proportion of hotels with high scores decreases. In fact, 6.85% of the smallest hotels in the sample (with a room capacity ranging from 1 to 30) received ratings of excellent (5), while this percentage did not even reach 1% amongst the remaining hotels in the sample, with the proportion dropping to 0% for hotels with a capacity of over 186 rooms. Also, 34.25% of the smaller hotels in the abovementioned interval received a rating of 4.5 or higher. In contrast, the proportion of hotels with similar ratings decreases progressively to 9.13% among larger hotels (room capacities ranging from 313 to 1,468 per hotel). On the other hand, if ratings above 4 are taken into account for all hotels, a trend shows that overall online ratings decrease as hotel room capacity increases up to the interval of 89 to 111 rooms, but beyond that point the trend no longer applies and the online rating retains an inverse relationship to hotel size.

5.5. Analysis of the relationship between the number of a hotels online qualitative reviews and its overall online rating

A hotels overall online rating tends to increase in line with an increasing number of qualitative online reviews posted for that hotel. Furthermore, if the number of review comments posted online for a hotel is compared to the size of that hotel (number of rooms), there are such statistically significant differences between average levels that it can be argued that there is a direct, positive relationship between the online customer rating and the NRNR ratio. In other words, as the number of qualitative online reviews posted per room increases, so does the overall online rating for that hotel.

In line with the statistical analyses outlined in previous sections, an analysis of variance was carried out in this case. First, the data was divided into 10 homogeneous intervals including hotels classified according to the number of online qualitative reviews received per room. The average score for each interval increases as the value of the NRNR ratio increases.

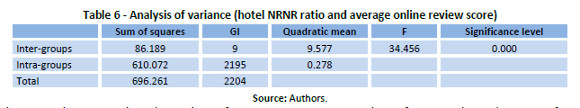

Levenes variance test for homoscedasticity was statistically significant at the level of 0.000<0.05, which resulted in the rejection of the null hypothesis (H0) as there is no equality of variances (see Table 6). Therefore, some measurements are significantly different, which confirms that there is a certain degree of relationship between a hotels NRNR ratio and its average online review score.

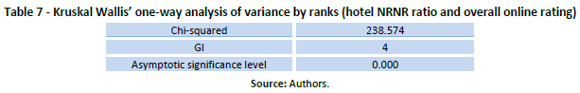

Nevertheless, in order to complete the analysis of variance considering that the normality test was not performed and homoscedasticity could not be demonstrated, Kruskal Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks was performed once again to confirm the results. The Kruskal-Wallis analysis was statistically significant at the 5% significance level (H0 rejected) (see Table 7). This supports the conclusion that there are statistically significant differences between the average levels outlined above and, therefore, there is a certain degree of relationship between the NRNR ratio and the overall online customer ratings of the hotels in this studys sample.

6. Conclusions and implications for the hospitality industry

Social media and customer review websites have changed the way the tourism and hospitality sectors are managed. This change implicates tourists and the way they access information to plan travel using online resources, as well as hotel managers and the way they manage their relationships with customers. This study presents an analysis of online hotel reviews posted by customers on TripAdvisor. The results of this analysis have important implications for the hospitality industry, which could help improve their online ratings and, consequently, their level of sales.

Firstly, this study found significant variations in the average number of online customer reviews for different hotels, their customer ratings and their NRNR ratios, which often depend on the tourism region where the hotels are located. Secondly, although there seems to be a certain degree of concern among hoteliers regarding customer review websites such as TripAdvisor, the majority of online customer reviews analyzed in this study were favorable, which is in line with earlier research conducted in the United States by Wei, Miao, & Huang (2013). Consequently, a reassessment may be necessary for some hotel managers, particularly those in smaller and medium-sized hotels, in regards to how they use social media to create more effective (and globally visible) customer relationship approaches. Similarly, the study has shown that the debatable perception among some managers in the hospitality industry that only customers who have extreme experiences on either end of the satisfaction spectrum tend to post online reviews is unfounded. The analysis showed that only 0.9% of the hotel online ratings found on TripAdvisor were in the excellent (5) category and none were in the terrible (1) category. Consequently, it seems that hotels should adopt a more active strategy to encourage their customers to post online ratings and reviews of their experiences. Nudge theory and similar marketing discourse may be particularly applicable in terms of further academic research and innovative business strategies for managers to capitalize on the emotional flow of the customer experience, starting with travel to their destination and ending well after their return home. This study has also shown that the number of online customer reviews per hotel room has a direct, positive relationship with a hotels overall customer rating. In fact, as this ratio (NRNR) increases, on average, customer ratings improve. This is an especially interesting relationship that merits further research and has important practical implications for the sector, particularly given that the value of the NRNR ratio decreases as the hotel size (number of rooms) increases.

On the other hand, there is a close relationship between the size of the hotel and its average online customer satisfaction rating. This study found that customers tend to award higher ratings to smaller hotels. As the size of the hotels studied increased, the number of high ratings tended to decrease accordingly. This has important implications for the hospitality sector. Firstly, smaller hotels can effectively compete with larger hotels by adopting a customer-focused quality-based approach, which should also be reflected in the way they manage online customer reviews. Secondly, smaller hotels need to be savvier about the type of customers they attract as well as the way these customers interact with different customer review websites. This reflects the findings of a study by Casaló et al. (2010), which found that customers willingness to participate in providing online reviews depends on the characteristics of the online community.

Given that smartphones, tablets and other similar mobile internet devices are becoming increasingly widespread among tourists, hotels can offer their customers free Wi-Fi access to encourage online reviews during their stay, which would help tap into key milestones in the emotional flow of their experience. This would also help hotels encourage customers to segment their reviews by services (e.g. bar, restaurant, gym, swimming pool, day trips offered by hotel, etc.), which would result in richer and more focused assessments of different aspects of their stay, adopting an essentially real-time approach. Similarly, hotels should encourage customers to post their feedback online within a given period of time after check-out, while the emotional engagement with their stay is still fresh in their minds. Additionally, hotels could offer one or more computers for customers to access the internet free of charge through a specific online customer review website where the hotel wants to increase its presence. It is important to note, however, that the use of other types of incentives are not considered here as they may attract a segment of customers motivated primarily by personal benefit.

Online hotel customer review websites can also serve a dual operational and strategic purpose. On the one hand, they can help hotel managers detect and address operational issues quickly (in some cases within hours of their occurrence) if customer reviews are monitored effectively, adopting a real-time approach. On the other, using a more reflective strategic perspective, comparisons made with other competitor hotels at the same destination can help hospitality businesses position themselves more effectively in the market.

Finally, this study has a number of limitations. Firstly, the analysis has been conducted using the overall customer rating in each case without regard to individual customer ratings for each hotel. Secondly, this study is quantitative and therefore ignores the content of the customer reviews posted online, which could have offered additional insight into the value of each hotels overall customer rating. Thirdly, the information collected in this study did not allow researchers to determine why smaller hotels tend to receive more online customer reviews per room than larger hotels. Further research could analyze individual customer ratings given to hotels over a period of time to establish the influence of factors such as motive or date of travel. Similarly, a semantic content analysis could be carried out in order to gain a better understanding of the reasons behind online customer review ratings for hotels. In addition, a random selection of online customer reviews could be carried out to pursue interviews with their authors, which would help us have a better understanding of their motivating factors and the relationship between these factors and the online hotel ratings they posted on TripAdvisor.

References

Anderson, C. K. (2012). The Impact of Social Media on Lodging Performance. Cornell Hospitality Report, 12(15), 4-11. [ Links ]

Bronner, F., & De Hoog, R. (2011). Vacationers and eWOM: Who Posts, and Why, Where, and What?. Journal of Travel Research, 50(1), 15-26. [ Links ]

Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Guinalíu, M. (2010). Determinants of the intention to participate in firm-hosted online travel communities and effects on consumer behavioral intentions. Tourism Management, 31(6), 898-911. [ Links ]

Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Guinalíu, M. (2011). Understanding the intention to follow the advice obtained in an online travel community. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 622-633. [ Links ]

Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., Guinalíu, M., & Ekinci, Y. (2015). Avoiding the dark side of positive online consumer reviews: Enhancing reviews' usefulness for high risk-averse travelers. Journal of Business Research, 68(9), 1829-1835. [ Links ]

Chaves, M. S., Gomes, R., & Pedron, C. (2012). Analysing reviews in the Web 2.0: Small and medium hotels in Portugal. Tourism Management, 33(5), 1286-1287. [ Links ]

Cunningham, P., Smyth, B., Wu, G., & Greene, D. (2010). Does Trip Advisor Make Hotels Better?. (Technical Report UCD-CSI-2010-06). Retrieved from School of Computer Science & Informatics, University College Dublin website: https://csiweb.ucd.ie/files/ucd-csi-2010-06.pdf. [ Links ]

Fernández-Barcala, M., González-Díaz, M., Prieto-Rodriguez, J., & Pestana-Barros, C. (2009). Factors influencing guests' hotel quality appraisals. European Journal of Tourism Research, 2(1), 25-40. [ Links ]

Ghose, a., Ipeirotis, P. G., & Li, B. (2012). Designing Ranking Systems for Hotels on Travel Search Engines by Mining User-Generated and Crowdsourced Content. Marketing Science, 31(3), 493-520. [ Links ]

Gretzel, U. (Dir.) (2007). Online Travel Review Study. Role & Impact of Online Travel Reviews. Retrieved from TripAdvisor: http://www.TripAdvisor.com/pdfs/OnlineTravelReviewReport.pdf. [ Links ]

Hashim, N. H., & Murphy, J. (2007). Branding on the web: Evolving domain name usage among Malaysian hotels. Tourism Management, 28(2), 621-624. [ Links ]

Instituto de Estudios Turísticos (2011). Informe Anual Frontur y Egatur 2010. Retrieved from http://www.iet.tourspain.es/es-ES/estadisticas/frontur/Anuales/Movimientos%20Tur%C3%ADsticos%20en%20Fronteras%20(Frontur)%20y%20Encuesta%20de%20Gasto%20Tur%C3%ADstico%20(Egatur)%202010.pdf [ Links ]

Jeong, M., & Jeon, M. M. (2008). Customer reviews of hotel experiences through consumer generated media (CGM). Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 17(1-2), 121-138. [ Links ]

Jurca, R., Garcin, F., Talwar, A., & Faltings, B. (2010). Reporting incentives and biases in online review forums. ACM Transactions on the Web, 4(2), 1-27. [ Links ]

Lado-Sestayo, R., Otero-González, L., & Vivel-Búa, M. (2014). Impact of the location and market structure in the performance of hotel establishments. Tourism & Management Studies, 10(2), 41-49. [ Links ]

Lee, K. H., & Hyun, S. S. (2015). A model of behavioral intentions to follow online travel advice based on social and emotional loneliness scales in the context of online travel communities: The moderating role of emotional expressivity. Tourism Management, 48, 426-438. [ Links ]

Leung, D., Law, R., Van Hoof, H., & Buhalis, D. (2013). Social media in tourism and hospitality: A literature review. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1-2), 3-22. [ Links ]

Levy, S. E., Duan, W., & Boo, S. (2013). An analysis of one-star online reviews and responses in the Washington, DC, lodging market. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(1), 49-63. [ Links ]

Limberger, P. F., dos Anjos, F. A., de Souza Meira, J. V., & dos Anjos, S. J. G. (2014). Satisfaction in hospitality on TripAdvisor. com: An analysis of the correlation between evaluation criteria and overall satisfaction. Tourism & Management Studies, 10(1), 59-65. [ Links ]

Liu, X., Schuckert, M., & Law, R. (2015). Online Incentive Hierarchies, Review Extremity, and Review Quality: Empirical Evidence from the Hotel Sector. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/10548408.2015.1008669 [ Links ]

Liu, Z., & Park, S. (2015). What makes a useful online review? Implication for travel product websites. Tourism Management, 47, 140-151. [ Links ]

López-Fernández, M. C., Serrano-Bedia, A. M., & Gómez-López, R. (2011). Factors encouraging innovation in Spanish hospitality firms. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 52(2), 144-152. [ Links ]

Luo, C., Luo, X. R., Xu, Y., Warkentin, M., & Sia, C. L. (2015). Examining the moderating role of sense of membership in online review evaluations. Information & Management, 52(3), 305-316. [ Links ]

Melián-González, S., Bulchand-Gidumal, J., & López-Valcárcel, B. G. (2013). Online Customer Reviews of Hotels: As Participation Increases, Better Evaluation Is Obtained. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(3), 274-283. [ Links ]

OConnor, P. (2010). Managing a Hotels Image on TripAdvisor. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 9(7), 754-772. [ Links ]

Ott, M., Cardie, C., & Hancock, J. (2012). Estimating the Prevalence of Deception in Online Review Communities. In Proceedings of the 21st international conference on World Wide Web, (pp. 201-210). New York: ACM. [ Links ]

Ott, M., Choi, Y., Cardie, C., & Hancock, J. T. (2011, June). Finding deceptive opinion spam by any stretch of the imagination. In Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Vol.1, (pp. 309-319). Stroudsburg: Association for Computational Linguistics. [ Links ]

Park, S. Y., & Allen, J. P. (2013). Responding to Online Reviews: Problem Solving and Engagement in Hotels. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(1), 64-73. [ Links ]

Park, S., & Nicolau, J. L. (2015). Asymmetric effects of online consumer reviews. Annals of Tourism Research, 50, 67-83. [ Links ]

Quinby, D., & Rauch, M. (2012). Social Media in Travel 2012. Social Networks & Traveler Reviews. Retrieved from PhocusWright: http://www.phocuswright.com/Travel-Research/Social-Search/Social-Media-in-Travel-2012-Social-Networks-Traveler-Reviews [ Links ]

Schuckert, M., Liu, X., & Law, R. (2015). Hospitality and tourism online reviews: Recent trends and future directions. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 32(5), 608-621. [ Links ]

Serra Cantallops, A., & Salvi, F. (2014). New consumer behavior: A review of research on eWOM and hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 41-51. [ Links ]

Sparks, B. A., Perkins, H. E., & Buckley, R. (2013). Online travel reviews as persuasive communication: The effects of content type, source, and certification logos on consumer behavior. Tourism Management, 39, 1-9. [ Links ]

Stringam, B. B., & Gerdes Jr, J. (2010). An analysis of word-of-mouse ratings and guest comments of online hotel distribution sites. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 19(7), 773-796. [ Links ]

Tejada, P., & Moreno, P. (2013). Patterns of innovation in tourism Small and Medium-size Enterprises. The Service Industries Journal, 33(7-8), 749-758. [ Links ]

TripAdvisor (2013a). TripBarometer. Retrieved from http://www.TripAdvisor.es/PressCenter-c4-Fact_Sheet.html [ Links ]

TripAdvisor (2013b). TripBarometer. Retrieved from http://www.TripAdvisortripbarometer.com/Spain [ Links ]

Verma, R., Stock, D., & McCarthy, L. (2012). Customer Preferences for Online, Social Media, and Mobile Innovations in the Hospitality Industry. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 53(3), 183-186. [ Links ]

Wei, W., Miao, L., & Huang, Z. J. (2013). Customer engagement behaviors and hotel responses. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 33, 316-330. [ Links ]

Xiang, Z., & Gretzel, U. (2010). Role of social media in online travel information search. Tourism Management, 31(2), 179-188. [ Links ]

Xie, K. L., Chen, C., & Wu, S. (2015). Online Consumer Review Factors Affecting Offline Hotel Popularity: Evidence from Tripadvisor. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/10548408.2015.1050538 [ Links ]

Yoo, K. H., & Gretzel, U. (2011). Influence of personality on travel-related consumer-generated media creation. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 609-621. [ Links ]

Zhou, L., Ye, S., Pearce, P. L., & Wu, M. Y. (2014). Refreshing hotel satisfaction studies by reconfiguring customer review data. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 38, 1-10. [ Links ]

Article history:

Submitted: 29.04.2015

Received in revised form: 13.01.2016

Accepted: 19.01.2016