Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Tourism & Management Studies

Print version ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.12 no.1 Faro Mar. 2016

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2016.12108

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Cruise passengers perceived value and willingness to recommend

Valor percebido e disposição para recomendar por parte dos passageiros de cruzeiros

David McA. Baker1, Mark D. Fulford2

1Tennessee State University, College of Business, Department of Business Administration, Suite J-405, Avon Williams Campus, Nashville, TN 37203, USA. E-mail: dmbaker@tnstate.edu

2Director of Client Services, SMG (Service Management Group),Kansas City, MO 64108 USA. E-mail: mfulford@smg.com

ABSTRACT

This paper evaluates cruise passengers perceived value, satisfaction and willingness to recommend a cruise to someone. Passengers aboard an underway ship cruising the Caribbean were surveyed. Regression analyses revealed that, not surprisingly, perceived value and service quality aboard the ship are key determinants of willingness to recommend a cruise to someone else. More interestingly, however, the quality of the food aboard the ship and the degree to which cruisers found the destinations to be relaxing were also significant indicators. Implications for future research and practical recommendations to cruise operators are discussed.

Keywords: Cruise, perceived value, satisfaction, willingness to recommend.

RESUMO

Este artigo avalia o valor percebido, a satisfação e a vontade de recomendar por parte dos passageiros de cruzeiro. Valor percebido, satisfação e vontade de recomendar um cruzeiro para alguém. Para o efeito foi aplicado um inquérito a passageiros bordo de um navio de cruzeiro nas Caraíbas. Análises de regressão revelaram que, não surpreendentemente, valor e serviço de qualidade percebida a bordo do navio são os principais determinantes da disposição de recomendar um cruzeiro a outra pessoa. Mais interessante, no entanto, a qualidade da comida a bordo e a medida em que os inquiridos consideraram os destinos relaxantes também foram indicadores significativos. Implicações para futuras pesquisas e recomendações práticas para os operadores de cruzeiros são discutidas.

Palavras-chave: Cruzeiros, valor percebido, satisfação, disposição de recomendar.

1. Introduction

Cruise tourism has been the fastest growing segment in the travel sector around the world. The cruise sector has experienced an important expansion over the past twenty years. Brida and Zapata (2010) reported an average annual growth rate of 7.4% in the number of worldwide cruise passengers taking cruises over the period 1990-2008. The participation of the cruise sector in the international number of tourists corresponds to approximately 2% while the revenue of cruise corporations represents about 3% of the total international tourism receipts (Kester, 2002; Klein, 2005; Dowling, 2006). The World Tourism Organization stated that international tourist receipts in 2011 were US$1.030 trillion. International tourist arrivals grew by over 4% in 2011 to 983 million tourists, according to the latest United Nations World Tourism Organization Barometer (UNWTO).With growth expected to continue in the next few years at a somewhat slower rate, international tourist arrivals are on track to reach the milestone one billion mark by the end of 2012. Similarly, the growth of cruise tourism is expected to continue into the future as only a small proportion of the population who have the resources to take a cruise have done so (Chase & McKee, 2003; Chase & Alon, 2002; Brida & Risso, 2010). Between 1990 and 1998, the cruise industry invested 9 $billion dollars in the launching of 36 major new vessels. No fewer than 30 cruise ships are expected to debut between 2013 and 2016. Keeping in mind that the industry is presently generating about 38$billion today, the confidence in the future of cruising by the cruise lines becomes readily apparent.

Today, cruise ships are becoming ever larger as the cruise lines struggle to achieve economies of scale. For those tourists who subscribe to the concept that bigger and newer is better, these are good times indeed. However, for those tourists who seek style and personalized services, there is considerably less to become excited about in terms of sheer quantity, but remarkably the highest standards of quality continue to be available on these cruise ships. One of the big changes in cruising has now become apparent, the new mega ships that are more resort than ship. The sea voyage with entertainment and leisure facilities within the ship has become as important and in some cases more important than the destinations reached. The excursions at the port are more important trip elements than the palaces visited (Weaver 2000). A new concept of cruising has emerged where cruise ships are coming to be seen as floating holiday resorts with non-stop entertainment on board. There is also another market for vessels of typically 3,000-10,000 tons, carrying around 100-200 passengers. They aim for a market willing to pay the higher prices such vessels demand; these much smaller ships are able to enter smaller harbors, canals and even bigger rivers. They also meet the demand for sustainable tourism in a better way than the big vessels, not only by their construction and fuel consumption but also in their ability to visit remote places without pouring 3,000-4,000 tourists into a fragile human or natural environment (Holloway 2002).

The ideal size for a cruise ship was thought during the 1960s and 1970s to be 18,000 to 22,000 tons, carrying some 650-850 passengers. Due to advanced technology, ships have been built since 1980 with a steadily growing tonnage of up to 100,000 tons (Holloway 2002). The Voyager of the Seas, 137,276 Gross Register Tonnage (GRT) and operated by Royal Caribbean Line, accommodating 3,114 passengers and with a skating rink, a climbing wall, street fair and a full-size basket court. Her sister ship, Explorer of the Seas, additionally houses a University of Miami-operated laboratory that allows passengers to observe oceanographic and atmospheric research. These opportunities are meant to keep passengers aboard the ship as much as possible. Long periods at sea are possible to cope with since the Voyager of the Seas has 35 bars and an extensive room service. Several of the largest cruise lines now operate their own private ports-of-call. Royal Caribbean have the two biggest cruise ships in operation today, Oasis of The Seas and Allure of The Seas came online in 2010 and 2011 respectively, each with 225,282 gross tonnage and 2706 staterooms. Although eight new ocean-going cruise ships were launched in 2012, the big news for the year seems to be in the river cruising sector of the industry, at least a dozen new river cruise ships were launched in 2012. There are more than 283 cruise ships operating worldwide today, of which 50 % operate outside US ports. In 1999, 60 % of all cruise passengers in the world were from the North American market rising to 68% in 2002, today its about 60.5%.

The Caribbean is the world's largest cruise shipping market, representing over 42% of the worldwide annual cruise supply (FCCA, 2011). It acts as an ideal cruising destination for the following reasons:

•Location, Location, Location! Being adjacent to the United States offers a large market of potential tourists able to afford cruise packages without having to travel far to start a cruising itinerary. Most Caribbean cruises begin and end from the Miami, Fort Lauderdale or Port Canaveral cruise ports cluster that act as the main hub ports. All are near major airports well connected to the rest of the United States and major touristic destinations in their own right. New York is also a significant hub port, but its distance limits its Caribbean ports of call options; Kings Wharf - Bermuda represents a common port of call for New York bound Caribbean itineraries. Itineraries using San Juan, Puerto Rico as a hub port have the advantage of being able to effectively cover the southern Caribbean in a week, the furthest from the United States.

•Geography. The Caribbean is mostly a chain of islands in close proximity implying short cruising distances between ports of call. The climate is subtropical with limited temperature fluctuations, albeit the hurricane season (September to November) can create some disruptions. There is a variety of landscapes ranging from rain forests to semi-arid conditions as well as the presence of coral and volcanic islands, all of which have high interest to tourists.

•Historical and cultural. The region has a long history associated with European colonialism and accounts for the oldest settlements in the Americas. African, Hispanic, English, French and Dutch influences are prevalent, conferring a very rich and diversified cultural landscape that often changes completely from one island to the other. Therefore, the cruise industry is able to offer to its customers a variety of cultural experiences in close proximity. Cruise ships can move from one Island to the other in less than a nights journey.

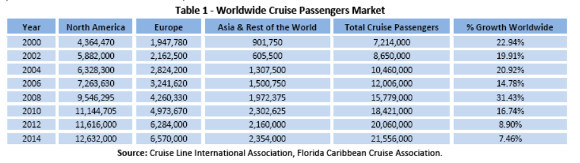

Given the state of the economy on a global scale, growth has slowed in the cruise sector as seen in Table 1. The number of cruise passengers worldwide has been increasing every year but at a slower pace since the downturn of the economy in 2008. The North American market in particular has seen much slower growth. This is a reason why, for cruise businesses, destinations and marketing strategies, it is essential to identify and analyze what factors influence repurchase and the intention to recommend a cruise to someone else. Although this is a very important topic, the literature has dedicated very little attention to this issue and the Caribbean in particular has had no study published on the subject. Only a few papers have studied the factors that affect a cruise ship passengers stated intention either of returning to a destination or to recommend it to friend and family (Gabe et al., 2006; Silvestre et al., 2008; Hosany and Witham, 2010; Andriotis and Agiomirgianakis, 2010). The present paper contributes to the literature by analyzing cruise visitors perceived value, satisfaction and intentions to recommend a Caribbean cruise, to date there has been no such studies done in the Caribbean islands. The main objective of the study is to identify cruise passengers perceived value of a Caribbean cruise and their willingness to recommend a Caribbean cruise. The empirical findings provided in this paper will contribute to the tourism industry, both academically and for practitioners. The Cruise line companies, destination managers, local government and policy makers will have valuable information to formulate private and public development and marketing strategies for repeat Caribbean tourism island cruise visits. Understanding why people take cruises and what factors influence their behavioral intention in recommending a cruise to someone else are fundamental for tourism planners and marketers.

2. Customer Perceived Value and Satisfaction

Customer-perceived value is defined as "the customer's evaluation of the difference between all the benefits and all the costs of a marketing offer relative to those use of competing offers (Kotler, 1994). The value concept created by Varki & Colgate (2001) is the most universally accepted and its the consumers overall assessment of the utility of a product based on perceptions of what is received and what is given. It is the comprehensive assessment of the utility of perceived benefits and perceived sacrifices, or as the difference between perceived benefits and paid costs; it is also the ratio of perceived benefits in relation to the perceived sacrifices. Sacrifices encompass all the costs (purchasing price, acquisition costs, installation), while perceived benefits are the combinations of physical attributes of the available service in a given relationship of the product. Customers often do not judge values and costs accurately or objectively, rather they act based upon their perceived value of the product. Therefore, Cruise ship companies should work hard to attract and retain customers by offering the highest customer-perceived value. According to Caruana (2004), satisfaction has been considered as one of the most important theoretical as well as practical issues for most marketers and customer researchers during the last four decades. Customer satisfaction refers to the degree to which customers perceive that they received products and services that are worth more than the price they paid (Jamal, 2004). Customer satisfaction enables business to measure from behavior of customer after they contact with organization, such as decreasing of customer complain, repurchasing, Tracey (1996), positive word of mouth, and increase the volume of purchases. Yoo & Park (2007), indicated that customer feedback data (customer knowledge sharing) leads to customer satisfaction including properly offering of products and services to individual customer needs (customer responsiveness) has an effect on customer satisfaction (Stefanou & Sarmaniotis, 2003).

Cruise passengers are the lifeblood of every cruise company, without them cruises would cease to trade and flourish. Risser (2003) indicated that no fewer than 80 of the Fortune 100 companies emphasized the importance of being customer-driven in their 2001 annual report. Kleymann and Seristo (2004) reported that a study conducted by Ernst & Young found that 77 percent of corporations that it surveyed identified knowledge about its customers as their most important criteria. Cruise companies must understand the distinctive behaviors, needs and preferences of their passengers to be able to deliver value. However, meeting rising customer expectations has proved to be one of the most difficult challenges to service businesses (Sonnenberg, 1991). Day (1999) argued that customers are becoming ever more demanding in a business environment where competition is getting fiercer; the cruise industry has become very competitive. The demand in the cruise business is created through pricing, branding and marketing. Cruise operators are challenged to develop competitive cruise packages which involve a high-quality stay onboard, an array of shore-based activities offering access to a variety of cultures and sites and easy transfers to and from the vessel. David (2001) offered a solution; he strongly argued that a firms marketing strategy must involve anticipating, creating and fulfilling customer needs and wants for products and services. Essentially, the marketing literature strongly advocates that the customer is pivotal to the entire business process, and the strategic marketing literature indicates that companies should place huge emphasis on their customers as they are crucial to strategy formulation.

The construct of perceived value has been identified as one of the most important measures for gaining a competitive edge (Parasuraman, 1997), and has been argued to be the most important indicator of repurchase intentions (Parasuraman & Grewal, 2000). In the past, quality has been recognized as a strategic tool to strengthen a firms competitive position and improve its profitability (Reicheld and Sasser 1990). However, Woodruff (1997) believed that customer value is the next underlying source of competitive advantage. Consistent with this view, Weinstein and Johnson (1999) considered that customer value is the strategic driver that differentiates a firms offering in a crowded marketplace. Perceived value has been defined as the consumers overall assessment of the utility of a product/service based on perceptions of what is received and what is given (Zeithaml, 1988). Within this definition, Zeithaml (1988) identified four diverse meanings of value: (1) value is low price, (2) value is whatever one wants in a product/service, (3) value is the quality that the consumer receives for the price paid and (4) value is what the consumer gets for what they pay. The majority of past research on perceived value has focused on the fourth definition (Bojanic, 1996; Zeithaml, 1985). Woodruff (1997) and also stated that received value leads to overall satisfaction, which is the customers feeling in response to an evaluation from using the product or service. Creating superior customer value is also a key to ensuring a companys long-term survival and success (Slater 1997; Woodruff 1997).

Consumers today are more sophisticated than ever and constantly demand value. Consequently, businesses are being told to be "high value" marketers and provide satisfaction if they want to remain profitable. To accomplish these goals, marketers must learn how to deliver value. But the mechanism through which consumers evaluate value is only vaguely understood; it is thought to be what consumers get, benefits for what they give up, costs. With the current emphasis on maintaining a long-term relationship with the customer, understanding how consumers determine value and satisfaction, and the link between the two concepts is a crucial topic for todays marketers. With the recent emphasis on delivering value and satisfaction to the customer, understanding what value and satisfaction means to the customer and how these concepts translate into repeat purchases, positive word-of-mouth activity and brand loyalty is a major concern for todays cruise lines. Bolton and Drew (1991) have suggested that value for services is more complex than a simple trade-off between quality and price. They operationalized value using multiple service dimensions that represent functional benefits. Likewise, drawing from focus group discussion, Zeithaml (1988) proposed that value might be more than a simple trade-off between a holistic measure of quality to represent benefits and price to represent costs.

Another reason for the disparities among studies of value and satisfaction involves the role of expectations to satisfaction and value. The question arises whether expectations contribute to perceptions of satisfaction and/or value or whether satisfaction and/or value are determined strictly from consumption outcome. Within the service literature there have also been mixed findings about whether expectations contribute to satisfaction. Cronin and Taylor (1992) raise concern about inclusion of expectations when assessing service quality and satisfaction with a service provider. They propose that performance alone is the best measure of service quality as an antecedent to satisfaction when contrasted against an expectation measure. In contrast, Parasuraman, Berry and Zeithaml (1991) propose expectations serve as a means by which consumers evaluate service quality and satisfaction. Essentially the literature emphasizes three principle reasons why companies should focus on satisfying their customers. Firstly, satisfied customers tend to be loyal and willing to pay higher prices (Reichheld and Sasser, 1990; Finkelman 1993, Johnson et al. 2005); secondly, satisfied customers serve as an advertising medium by positive word of mouth (Howard and Sheth, 1969; Reichheld, 2003) which helps to acquire new customers; and thirdly, customer satisfaction is a significant component of repeat service usage or of repeat purchasing (Mittal and Kamakura, 2001; Oliver 1999).

Overall satisfaction is defined as a function of satisfaction with multiple experiences or encounters with the organization. Satisfaction is the level of enjoyment or disappointment, originating from expectation of the product (Kotler, 2003). To be precise, satisfaction is a person's feelings of pleasure or disappointment resulting from comparing a product's perceived performance or outcome in relation to his or her expectations (Kotler, 2000). The consumer is satisfied or not with the product, whereas pre-purchase evaluation is related to a function of products (Engel et al.,1995). Teye and Leclerc (1998) presented the results of an exploratory study that examined passengers' satisfaction with the cruise experience, the results of the study showed that overall, passengers' expectations were met or exceeded. Nicholls et al., (1999) showed that cruise lines earned significantly higher satisfaction for both the personal service received and the setting in which the service was provided. Tourism and hospitality research have recently shown an interest in value, especially when investigated with quality and/or satisfaction (Gallarza and Saura, 2006). Customer satisfaction is viewed as a function of perceived performance and expectations and consumer behavioral studies show that customers who are only just satisfied still find it easy to switch over when a better offer comes along. High satisfaction or delight creates an emotional bond with the brand, not just a rational preference, and can result in high customer loyalty (Lee et al., 2007). It is clear that if performance falls short of expectations, the customer is dissatisfied, and if performance matches or exceeds expectations, the customer is highly satisfied or delighted.

Destination image, perceived quality, perceived value and satisfaction (Bigne et al., 2001; Pike, 2002; Chen & Tsai, 2007; Chi & Qu, 2008; Chen & Chen, 2010) are the most frequent factors used to explain tourist motivation or intention to visit/revisit a tourist destination. Customer satisfaction is one of the most frequently examined topics in the hospitality and tourism field because it plays an important role in survival and future of any tourism products and services (Gursoy, McCleary & Lepsito, 2003). It also significantly influences the choice of destination, the consumption of products and services, and the decision to return (Kozak & Rimmington, 2000). Satisfaction has always been considered essential for business success. However, interest in studying the measurement of satisfaction has moved towards the concept of loyalty, as it enables better prediction of consumer behaviour which is key to business continuity (Chi & Qu, 2008). Past studies have suggested that perceptions of service quality and value affect satisfaction, and satisfaction furthermore affect loyalty and post-behaviors (Oliver, 1999; Cronin & Taylor, 1992; Fornell, 1992; Anderson & Sullivan, 1993; Tam, 2000; Bignie, Sanchez & Sanchez, 2001; Petrick & Backman, 2002; Chen & Tsai, 2007; Chen, 2008; De Rojas & Camarero, 2008). For example, the satisfied tourists may revisit a destination, recommend it to others. On the other hand, dissatisfied tourists may not return to the same destination and may not recommend it to other tourists (Reisinger & Turner, 2003). The concept of loyalty has been recognised as one of the more important indicators of corporate success in the marketing literature (La Barbara and Mazursky, 1983; Turnbull and Wilson, 1989; Pine et. al., 1995; Bauer et. al., 2002). Hallowell (1996) provides evidence on the connection between satisfaction, loyalty and profitability. The author refers that working with loyal customers reduces customer recruitment costs, customer price sensitivity and servicing costs. In terms of traditional marketing of products and services, loyalty can be measured by repeated sales or by recommendation to other consumers (Pine et al., 1995). Yoon and Uysal (2005) stress that travel destinations can also be perceived as a product which can be resold (revisited) and recommended to others (friends and family who are potential tourists).

2.1 Relation of perceived value to satisfaction and future intention

A great deal of research suggests that perceived value is an important predictor and key determinant of customer satisfaction and future behavior (Cronin et al., 2000; McDougall and Levesque, 2000; Parasuraman and Grewal, 2000; Petrick and Backman, 2002; Sánchez et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007). The foundation of behavioral intentions comes from the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) which is one of the most influential models in predicting human behavior and behavioral dispositions. The theory proposed that behavior is affected by behavioral intentions which, in turn, are affected by attitudes toward the act and by subjective norm. The first component, attitude toward the act, is a function of the perceived consequences people associate with the behavior. The second component, subjective norm, is a function of beliefs about the expectations of important referent others, and his/her motivation of complying with these referent, implying that if the individual believes that others would encourage the behavior, the individual would be more likely to engage in the behavior. The determinants of intentions can be both personal and impregnate with social influence. The model is based on three constructs: attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control, all of which can be applied to tourists travel behavior. The travel behavior of tourists and their destination choice have attracted many scholars for the past few decades but Caribbean cruise ship travelers satisfaction and behavioral intention has had little empirical investigation. Since it is in our interest to understand peoples behavior, we must also identify the determinants of intentions. People are expected to act in accordance with their intentions (Kuhl et al., 1985).

In the marketing literature, several researchers have tested the relationship between value, satisfaction and future intention. For example, Woodruffs (1997) study found that perceived value was antecedent to overall customer satisfaction and that this, in turn, correlated well with customer behaviors such as word of mouth, recommendations and intention to repurchase. Cronin et al.(2000), examined the relationships among service value, satisfaction and future intention where value was found to have an effect on customer satisfaction and behavior within six different industries except for health care. Patterson and Sprengs (1997) study indicated that value was significantly correlated with satisfaction, which, in turn, influenced repurchase intention. Wang et al.(2004) tested relationships among four different factors: value, satisfaction, brand loyalty and performance. The results revealed that only functional value had a significant effect on customer satisfaction, brand loyalty and behavioral performance. The rest of the factors such as social value, emotional value and perceived sacrifice appeared to only impact customer satisfaction.

Gallarza and Sauras (2006) study revealed that perceived value correlated with tourist satisfaction significantly, which, in turn, had an effect on their loyalty. Lee et al. (2007) study showed that three dimensions of functional, overall and emotional values had a significant effect on satisfaction. The influence of international tourist satisfaction on intent to recommend the trip to others was found to be statistically significant. Anderson and Sullivan (1993) mentioned that consumer satisfaction affects re-purchase behavior. In addition, the relationship between satisfaction and loyalty is positive. Cronin et al. (2000) reported an empirical verification that satisfaction directly related to behavioral intentions in the service environment. Baker and Crompton (2000) pointed out that higher satisfaction increases tourists repurchase intention, moreover, they would also tolerate higher prices. Lobo (2008) found that overall customer satisfaction had a relatively strong relationship with all three variables of behavioral intentions in the cruise line industry. Customer satisfaction has a direct and positive impact on purchase intentions (Bai et al., 2008).

Petrick et al. (2006) indicated that moment of truth is a critical incident technique for management to better understand cruise passengers overall satisfaction, perceived value, word of mouth, and repurchase intentions. As a cruise ship is an intermediary type of transportation, this is another factor to take into account concerning the tourists travel experience; hence, this research focuses on positive behavioral intentions. Rao and Monroe (1989); Monroe (1990); Chang and Wildt (1994) argued that perceived value is affected by the information obtained by consumers. This then influences consumers purchase intention. According to the results from Petrick and Backman (2002), both satisfaction and perceived value can explain post-purchase behavioral intention; satisfaction is predominant in explaining loyalty. Swait and Sweeneys (2000) empirical research concentrated on consumers perceived value and the resulting behavior. Eggert and Ulaga (2002) suggested a direct impact of perceived value on the purchasing intentions by purchasing managers in Germany. Petrick (2003) indicated that service perceived value factors are related to cruise passengers' post-cruise cognitive assessments. Petrick (2004) found that satisfaction and perceived value were the best predictors of repurchase intentions for repeaters on cruise ships.

Duman and Mattila (2005) expanded perceived value by demonstrating the role of selected affective factors on value in the context of cruise vacation experiences to examine the role of customer satisfaction in the affect–value relationship. The results indicated that these affective factors were determinants of the perceived value of cruise services. Silvestre et al. (2008), evaluated the satisfaction of cruise passengers visiting the Atlantic islands of the Azores Archipelago. Their study investigated the relationship between cruise passengers satisfaction with the Azores and their behavioral intentions, not only with regard to repurchasing the cruise but also to the likelihood of their recommending it and the Azores to friends and relatives. The findings revealed that, besides value for money, the two main factors driving the behavioral intentions were linked, first, to the city, its attractions in general and the individual's level of satisfaction with the overall visit and, second, and of lesser importance, to the perceptions of hospitality, safety, services and cleanliness of the environment in the Azores.

Shiang et al. (2011)examined cruise image as a recreational experience and compared the results to investigate perceived value, satisfaction and post-purchase behavioral intention. . The results showed that cruise image has a positive effect on tourists perceived value and satisfaction, and also had an indirect effect on post-purchase behavioral intention. Tourists perceived value influences their satisfaction positively. Plus, tourists perceived value and satisfaction play a significant role in post-purchase behavioral intention. Tonner & Quinn (2006) study examined cruise passengers moments of truth using critical incident technique to better understand cruise passengers overall satisfaction, perceived value, word of mouth, and repurchase intentions. Results imply that analyzing critical incidents can be an effective management tool for cruise line management and that these moments of truth are relevant to visitor retention. It was also found that negative incidents have a much greater effect on cruise passengers post hoc cruise evaluations than positive incidents, thus affecting behavioral intentions.

Operationalizing the construct of loyalty in the tourism industry may turn out to be a complex task. Those who have written on this matter have chosen to use a wide variety of conceptualizations in their causal models of the determinants of loyalty in tourism. For this reason and with the aim of offering an overview of research on this construct in the literature, the objective of this present study is to examine the treatment and the operationalization of the loyalty construct in tourism, based on the results of several studies found in the literature review carried out. The research that has been examined focuses on what produces loyalty to destination, accommodation and other tourism products of interest and that was published in the form of either scientific articles or doctoral theses. The question at stake is, therefore, to find out how to measure loyalty on the basis of those elements that generate value for the tourist at the destination level. Loyalty in the tourism sector has been poorly studied, so there are many outstanding questions about how to keep these particular customers loyal in the long-term (Zamora et al. 2005). Tourism has seen the introduction of relationship marketing techniques and indeed has been in the vanguard of the industries that have adopted this focus. Nevertheless, the concept of destination loyalty has received little attention in the literature (Fyall et al. 2003; Yoon and Uysal 2005) and neither have companies that offer accommodation (Aksu 2006).

Today destinations face the toughest competition in decades and it may become tougher still in years to come so marketing managers need to understand why tourists are faithful to destinations and what determines their loyalty (Chen and Gursoy 2001). One might usefully ask whether a particular destination can generate loyalty in people who visit it. In this regard Alegre and Juaneda (2006: 686) hold that some tourism motivations would inhibit destination loyalty, such as, for example, the desire to break with the monotony of daily life, engage with new people, places and cultures or look for new experiences. However, risk-averse people may feel the need to revisit a familiar destination. Barroso et al. (2007) found four groups of tourists, on the basis of the need for change which tourists have when it comes to taking a trip. These groups show significant differences depending on the intention of the tourists to return or to recommend the destination. Riley et al. (2001) note that the literature on loyalty demonstrates a problem in its conceptualization, to be resolved by empirical means or operational definitions, depending on the purpose of the study. From the classical viewpoint, loyalty is a difficult to define abstraction because of the different roles it can play. This depends on the antecedents of attitudes and values, the repetition behavior and the specific characteristics of the object of loyalty. As a concept, it involves the power to attract the object and the propensity to commit the individual. The empirical question to be answered is what pattern of behavior in tourism consumption can be interpreted as an indicator of loyalty.

Yoon and Uysal (2005) note that destinations can be considered as products and tourists can visit them again or recommend them to other potential tourists such as friends or family. Chen and Gursoy (2001) operationally defined destination loyalty as the level of tourists perception of a destination as a good place, one that they would recommend to others, noting that studies which only consider repeat visits as an indicator of loyalty to the destination are deficient. This is because those who do not return to a particular destination may simply find different travel experiences in new places, while maintaining loyalty to the previously visited destination. Also, these authors argue for the intention to recommend a destination as an indicator of loyalty. An airline ticket has the potential to be sold routinely, but with regard to a trip to a particular destination it may be unlikely that a purchase would actually occur, so that willingness to recommend the product could be an appropriate indicator for measure of loyalty to the destination concerned. Therefore they point out that tourism researchers should use appropriate variables to evaluate the loyalty of the tourist to a specific tourism product. Accordingly to the above considerations, the following research hypotheses are formulated:

H1: Cruise passengers satisfaction holds a positive influence on willingness to recommend

H2: Cruise passengers satisfaction holds positive influence on the cruise experience

3. Methodology

In an attempt to determine the nature and relationships between cruisers satisfaction with the cruise experience, perceived value, and willingness to recommend a cruise to someone else, an exploratory study was conducted aboard a ship cruising the Western Caribbean. On the Carnival Liberty cruise ship, one of the authors accompanied 16 students from his tourism class on a cruise of the Caribbean ports of Cozumel, Belize City, Rotan Island and Grand Cayman Island. In order to learn more about tourism and cruising, each student was instructed to speak to passengers on the ship after the last port of call and ask if they would be willing to complete a brief survey about their experiences. The students were trained in class on how to solicit participation from cruise passengers. The reason for this was to observe activities and behaviors of passengers on board the cruise shipand at the destinations and to enable the researcher and students to experience directly the ways in which passengers were experiencing the cruise.Given the scarcity of data on most aspects of cruise visitors experience in the Caribbean this current study was conducted. Following discussion with travel agents on issues related to cruisers experiences, hospitality and tourism professors, a review of past studies, such as Duman and Mattila (2005) and Qu, Wong & Ping (1999), Andriotis and Agiomirgianakis (2010), a self-completed questionnaire was designed. The cover letter provided information about the general purpose of the study, detailed instructions for administering the questionnaires, the data collection procedure and a request to fully complete the questionnaire. Baker 1994; Polit et al., 2001; De Vaus (1993 ) stated that one of the advantages of conducting a pilot study is that it might give advance warning about where the main research project could fail, where research protocols may not be followed, or whether proposed methods or instruments are inappropriate or too complicated. The questionnaire was pilot tested (n=50) with cruise passengers six months earlier, their comments were used to revise and clarify the statements in the survey, the final version was then edited. The first section of the questionnaire contained questions about respondents profile utilizing socio-demographic variables (age, gender, marital status, education, income, employment status and geographic origin), travelling party and major source of information used to book the cruise. The second section asked respondents to indicate their level of satisfaction, while the third section dealt with attributes which affect various components of the cruise experience (e.g., quality of service received on board ship, itinerary, accommodations, quality of food & beverages served on board, etc.). A 5-point Likert type scale, ranging from 5=extremely satisfied to 1=very dissatisfied was used to assess respondents agreement with a set of statements. In all, 314 useable surveys were completed. This represents approximately 8% of the 4,000 passengers on board the ship during this particular cruise. The vast majority (243; >77%) of respondents were from the United States (USA). Outside of the USA, Canada (32; >10%) and UK (9; <3%) were the countries most represented. Gender representation among the respondents was almost evenly split: 138 males; 164 females. Respondents ranged in age from 18 to more than 75 years of age. They were evenly split between those aged 18-44 and those aged 45 or greater.This was the first cruise experience for about 36% (114) of the respondents, while almost 64% (199) indicated they had previously been on a cruise.

4. Results

This study finds a significant cause-effect relationship between travel satisfaction and destination loyalty as well as willingness to recommend and the cruise experience. Oh (1999) establishes service quality, perceived price, customer value and perceptions of company performance as determinants of customer satisfaction which, in turn, is used to explain revisit intentions. Bigne et al. (2001) identify that returning intentions and recommending intentions are influenced by tourism image and quality variables of the destination. Kozak (2001) model intentions to revisit in terms of the following explanatory variables: overall satisfaction, number of previous visits and perceived performance of destination. In a recent paper, Um et al. (2006) propose a structural equation model that explains revisiting intentions as determined by satisfaction, perceived attractiveness, perceived quality of service and perceived value for money. In this study repeat visits are determined more by perceived attractiveness than by overall satisfaction. The study of the influential factors of destination loyalty is not new to tourism research. Some studies show that the revisit intention is explained by the number of previous visits (Mazurki, 1989; Court and Lupton, 1997; Petrick et al., 2001). Besides destination familiarity, the overall satisfaction that tourists experience for a particular destination is also regarded as a predictor of the tourists intention to prefer the same destination again (Oh, 1999; Kozak and Rimmington, 2000; Bowen, 2001; Bigné and Andreu, 2004; Alexandros and Shabbar, 2005; Bigné et al., 2005).

Yoon and Uysal (2005) use tourist satisfaction as a moderator construct between motivations and tourist loyalty. Recently, Um et al. (2006) propose a model based on revisiting intentions that establishes satisfaction as both a predictor of revisiting intentions and as a moderator variable between this construct and perceived attractiveness, perceived quality of service and perceived value for money. More complex models have the advantage of allowing a better understanding of tourist behavior since more variables and their interactions can be taken into account. However, for more effective marketing interventions it is important to assess whether the destination models also consider the tourists personal characteristics (Woodside and Lysonski, 1989; Um and Crompton, 1990). In fact, despite the use of more comprehensive models, so far, they have left unspecified the main personal characteristics (socio-demographic and motivational) of the more potentially loyal and satisfied tourists. The contribution of this study lies in bridging this research gap. This study integrates the main stream of previous research on destination loyalty intention proposing a causal relationship between this construct and satisfaction. However, besides estimating this causal model, the paper aims to identify how observed variables of the latent constructs are related and, next, find and describe segments of tourists based on these relations.

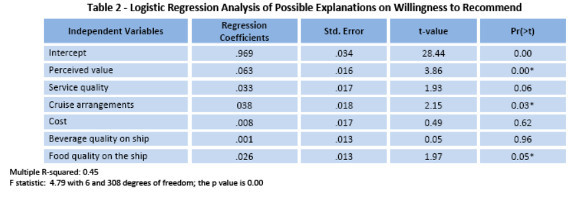

In an attempt to determine the key factors leading to cruisers willingness to recommend a cruise to someone else, a logistical regression analysis was conducted on the responses to those items on the questionnaire offering possible explanations. Logistical regression was used in this case due to the non-linear nature of the dependent variable (i.e., one requiring responses of yes/no), which violates one of the assumptions of linear regression. Logistical regression transforms a non-linear relationship into a linear one and allows for the interpretation of the data similar to a normal regression equation (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). Table 2. lists the pertinent items and the resulting statistical significance associated with each. As can be seen in Table 2, three variables were statistically significantly related (at p< .05) to the respondents willingness to recommend a cruise to someone else: they were I am satisfied with the value (what you got for what you paid) of my cruise ship experience, The cruise arrangements (i.e., itinerary, accommodations, spa, shows, casino, etc.) are consistent with what was promised, and The food available on the cruise ship is great. Together, these variables explained a statistically significant amount (roughly 45%) of the variation in respondents willingness to recommend a Caribbean cruise to someone.

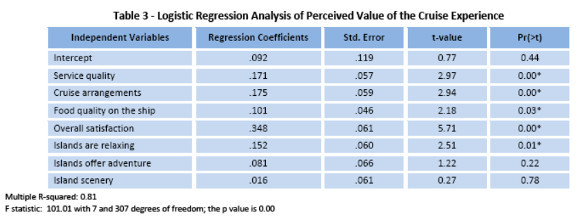

Next, an analysis was conducted on the key determinants of perceived value. Another logistical regression was run (for the same reasons as stated before): this time the dependent variable was a Likert-type item with 5 response choices; there were seven Likert-type independent variables (also with 5 response choices each) included in the analysis. Table 3. contain those 7 items and the resulting statistical significance associated with each.

As can be seen in Table 3, five of these items were statistically significantly related (at p< .05) to cruisers perceived value associated with the cruise experience: The quality of service I received on this cruise met my expectations; The cruise arrangements (i.e., itinerary, accommodations, spa, shows, casino, etc.) are consistent with what was promised; The food available on the cruise ship is great; I am very satisfied with this entire Caribbean cruise experience; and The Islands are relaxing destinations. Together, these variables explained a statistically significant amount (roughly 81%) of the variability in respondents perceived value of the cruise experience.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

The finding that perceived value significantly predicted willingness to recommend was consistent with prior research findings (Cronin et al., 2000; Baker and Crompton, 2000; Petrick and Backman, 2002; Petrick et al., 2006; Sánchez et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007). The tourists post-purchase behavioral intention is positively affected by perceived value and satisfaction; this finding is consistent with findings previously reported. The next logical question, and the one we were especially interested in identifying in this study, is: Then, what are the key contributors to perceived value? This focuses on the more practical side of things: those factors that have a positive impact on passengers willingness to recommend a cruise to someone else. From Table 3, you can see there are several factors which significantly contributed to passengers perceptions of value. Not surprisingly, overall satisfaction with the cruise experience was one such factor. It goes to reason that perceived value (what you got for what you paid) cannot be high without first being satisfied with what was gotten. This relationship, while intuitive, has also been borne out by a plethora of previous studies (Teye and Leclerc, 1998; Nicholls et al., 1999; Tonner & Quinn 2006; Lee et al., 2007; Petrick, 2003, 2004; Petrick et al., 2006). Similarly, the quality of service received on the cruise was found to be significantly related to perceived value. Again, this relationship is not surprising and is consistent with some prior findings (Gallarza and Saura, 2006; Duman and Mattila, 2005).

Qu and Ping (1999) indicated that the major travel motivation factors of cruise ships were escape from normal life, social gathering, and beautiful environment and scenery; moreover, tourists report a high satisfaction level with food, beverages, facilities, quality, and staff performance on board cruise ships. From the tourists point of view, the main reasons to purchase this kind of trip are entertainment and trying out the cruise experience. In addition, travel companions are friends and family. Therefore, the most important inducements to repeat a cruise are likely to be entertainment, then experience image of such factors as accommodation, food a beverages in great facilities. In this study approximately 64% tourists have taken a cruise before. That is to say, around two thirds of tourists are loyal to taking the cruise again. The cruise trip affords views of seascapes and various sights while accommodating the passengers in a floating resort; the tourists enjoy the entertainment facilities just as they would the life of a resort or island or seaside. Therefore, it is suggested that the various organizers should take entertainment into account to increase tourists post-purchase behavioral intention. In this research, the empirical evidence shows that cruise image positively influences tourists perceived value, satisfaction and willingness to recommend. We suggest that trying to give tourists a positive cruise image can effectively increase tourists satisfaction. Because image involves both tour information obtained in advance and post-tour impressions, executives should create various marketing strategies to shape a unique traveling product with a particular image (such as ocean-going casino ships) aimed at attracting the tourist who has never been on a cruise ship. Travel by cruise ship can take the tourist to a number of countries, even sailing round the world, like a moving hotel. The guests do not have to be troubled with luggage arrangements and different accommodation while travelling. According to our results, tourists perceived value positively influences their satisfaction, and tourists positive post-purchase behavioral intention is positively influenced by their satisfaction and perceived value. In order to increase tourists loyalty, we maintain that it is crucial to pay attention to what managers actually offer to tourists and what the tourists expect. Tourists perceive greater value when they get more than they were expecting; this kind of value can be transferred to satisfaction. Also, the positive cruise image can positively influence tourists perceived value and satisfaction; therefore we do not emphasize tourists perceived value and satisfaction without also looking at cruise image.

What is especially interesting to note are the findings with regards to food quality and relaxing destinations. When talking to anyone who has recently completed a cruise, when asking about the experience, they will typically mention the food (24-hour availability, variety, quality, etc.). However, these are anecdotal accounts; this study provides empirical evidence of the significance of the food that is offered aboard the ship. Given the amount of time spent aboard the ship, it was somewhat surprising to find a quality related to the destinations themselves to be a key driver of perceived value. Passengers appear to value destinations that offer the opportunity to relax. As a whole, these findings are substantiated by the results of a study appearing in a recent November issue of Travel & Leisure Magazine (Potter, 2012). When attempting to determine the worlds best airline, air passengers were asked to evaluate each carrier on the following criteria: cabin comfort, in-flight service, customer service, value, and food. And while no one boards a plane for the sake of eating, better-than-average in-flight meals did have an impact on the results.

One of the strongest advantages of the current study is the utilization of actual cruise passengers as respondents and capturing their responses during an ongoing cruise. Most prior research utilizes a random sample of respondents (some that are experienced cruisers; some that are not) and surveys their recollections of the experience long after the cruises have concluded. There are a few limitations to point out related to this study. First, the outcome variable of interest, willingness to recommend a cruise to someone else, was ascertained via cruise passenger self-report. Basically, the passengers surveyed were reporting on their intent to recommend, as opposed to the actual behavior of recommending. It was not possible in this study to track passengers subsequent to the completion of the cruise and to record the extent to which they actually made such recommendations. However, consistent with the seminal works of Fishbein & Azjen (1975), capturing passengers intent to recommend is a legitimate precursor and predictor of actual recommendation behavior. Second, the current study used a convenience sample (i.e., those on board the ship that agreed to participate). However, given the sample size (and its representative nature of the population of passengers onboard the ship at that time), this was not felt to be an issue for concern.

There are both academic and practitioner implications from the present study. First, from an academic perspective, replication is necessary. To increase generalizability, future research should be attempted whereby passengers on several different cruises (aboard several different ships) are surveyed while the cruises are underway. From a practical perspective, cruise operators are encouraged to focus on the quality of service and food offered on the ship, as well as ensuring the scheduled destinations offer ample opportunities for passengers to relax. In so doing, cruise operators can maximize the likelihood that passengers will perceive the value of their cruise experience to be high and, in turn, will recommend to others that they pursue a similar experience. In times of such economic uncertainty, this is one way to capture patronage (and hopefully repatronage); ultimately leading to increased revenues and ongoing viability.

6. Limitations and suggestions for future research

Although the overall results of this study are quite encouraging, their implications may be limited by several considerations. The limitations of our study opened pathways for future research. First of all, since the population of this survey was limited to cruise passengers on one cruise ship, the generalizability of the findings may not be a good idea. Both cross-sectional and longitudinal future research can help determine whether different cruise passengers on various cruise ships will yield similar results. Secondly, our study examined only perceived value and willingness to recommend. Since additional variables, such as customer value (e.g. Chen & Chen, 2010), emotions (Yüksel & Yüksel, 2007) and motivation (e.g. Yoon & Uysal, 2005), may also predict customer behavior, further research is necessary to investigate the antecedent role of these additional variables in the cruise industry.

References

Aksu A (2006) Gap analysis in customer loyalty: a research in 5 star hotels in the Antalya region ofTurkey. Qual Quant, 40(2), 187–205. [ Links ]

Alegre J, Juaneda C (2006) Destination loyalty, costumers economic behavior. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(3), 684–706. [ Links ]

Alexandros A., Shabbar, J. (2005). Stated preferences for two Cretan heritage attractions. Annals ofTourism Research, 32(4), 985-1005. [ Links ]

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. Springer Series in Social Psychology (pp. 11–39). Berlin: Springer. [ Links ]

Anderson, E. W., & Sullivan, M. W. (1993). The Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Satisfaction for Firms. Market Science, 12 (2), 125–143. [ Links ]

Andriotis, K., & Agiomirgianakis, G. (2010). Cruise visitors experience in a Mediterranean port of call. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12 (3), 390–404. [ Links ]

Bai, B., Law, R., & Wen, I. (2008). The impact of website quality on customer satisfaction and purchase intentions: Evidence from Chinese online visitors. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27(3), 391–402. [ Links ]

Baker, D. A., & Crompton, J. L. (2000). Quality Satisfaction Behavioral Intentions. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(3), 785–804. [ Links ]

Baker, T.L. (1994). Doing social research (2nd Edn.). New York: McGraw-Hill Inc. [ Links ]

Barroso C, Martín E. & Martín D. (2007) The influence of market heterogeneity on the relationship between a destinations image and tourists future behavior. Tourism Management, 28(1), 175–187. [ Links ]

Bauer, H., Mark, G., & Leach, M. (2002). Building customer relations over the internet. IndustrialMarketing Management, 31(2), 155-163. [ Links ]

Bigné, J.E., & Andreu, L. (2004). Emotions in segmentation: an empirical study. Annals of TourismResearch, 31(3), 682-696. [ Links ]

Bigné, J. E., Andreu, L., & Gnoth, J. (2005). The theme park experience: an analysis of pleasure,arousal and satisfaction. Tourism Management, 26(6), 833-844. [ Links ]

Bigné, E., Sánchez, M. I. & Sánchez, J. (2001). Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationship. Tourism Management, 22(6), 607–616. [ Links ]

Bojanic, D. C. (1996). Consumer perceptions of price, value and satisfaction in the hotel industry: An exploratory study. Journal of Hospitality and Leisure Marketing, 4 (1), 5–22. [ Links ]

Bolton, R. N. & Drew, J. H. (1991). A multistage model of customers assessments of service quality and value. Journal of Consumer Research, 17 (March), 375–384. [ Links ]

Bowen, D. (2001). Antecedents of consumer satisfaction and dis-satisfaction (CS/D) on Long-Haul inclusive tours: a reality check on theoretical considerations. Tourism Management, 22, 49–61. [ Links ]

Brida, J. G., Lanzilotta, B., Lionetti, S. & Risso, W.A. (2010). The tourism-led-growth hypothesis for Uruguay. Tourism Economics, 16 (3), 765–771. [ Links ]

Brida, J. G. & Zapata Aguirre, S. (2010). Cruise tourism: economic, socio-cultural and environmental impacts. International Journal of Leisure and Tourism Marketing, 1(3), 205–226. [ Links ]

Caruana, A. (2004).The impact of switching costs on customer loyalty: A study among corporate customers of mobile telephony. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 12(3), 256-268. [ Links ]

Chang T. Z., & Wildt A. R. (1994). Price, product information, and purchase intention: an empirical study. Journal of Academic Marketing Science, 22(1), 16–27. [ Links ]

Chase, G. L., & McKee, D. L. (2003). The economic impact of cruise tourism on Jamaica. Journal of Tourism Studies, 14(2), 16–22. [ Links ]

Chase, G., & Alon, I. (2002). Evaluating the economic impact of cruise tourism: a case study of Barbados. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 13(1), 5–18. [ Links ]

Chen, C. (2008). Investigating structural relationships between service quality, perceived value, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for air passengers: evidence from Taiwan. Transportation Research Part A, 42(4), 709–717. [ Links ]

Chen, J.S., Gursoy, D. (2001). An investigation of tourists destination loyalty and preferences. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 13(2), 79–85 [ Links ]

Chen, C. & Tsai, D. (2007). How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tourism Management, 28, 1115–1122. [ Links ]

Chen, C. & Chen, F. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management, 31, 29-35. [ Links ]

Chi, C. & Qu, H. (2008). Examining the structural relationship of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: an integrated approach. Tourism Management 29(4), 624–636. [ Links ]

Cohen J. & Cohen P. (1983). Applied multiple regression-correlation for the behavioral sciences ( 2nd edition). Hillsdale, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Court, B., & Lupton, R. (1997). Customer portfolio development: modelling destination adopters, inactives, and rejecters. Journal of Travel Research, 36(1), 35–43. [ Links ]

Cronin J. J., Brady M. K., & Hult G. T. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 193–218. [ Links ]

Cronin, J.J. & Taylor, S.S. (1992). Measuring service quality: a re-examination and extension. Journal of Marketing, 6(7), 55-68. [ Links ]

Cruise Line International Association. Assessed May 28, 2015, www.cruising.org [ Links ]

David, F. (2001). Strategic Management Concepts (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River NJ: Macmillan. [ Links ]

De Rojas, C. & Camarero, C. (2008). Visitors experience, mood and satisfaction in a heritage context: evidence from an interpretation center. Tourism Management, 29, 525–537. [ Links ]

De Vaus, D.A. (1993). Surveys in Social Research (3rd edn.). London: UCL Press. [ Links ]

Dowling, R. K. (2006). Cruise Ship Tourism. London: ABI Publishing. [ Links ]

Duman T. & Mattila, A.S. (2005). The role of affective factors on perceived cruise vacation value. Tourism Management, 26(3), 311-323. [ Links ]

Eggert, A., & Ulaga, W. (2002). Customer perceived value: a substitute for satisfaction in business markets. Journal of Business Industry and Marketing, 17(2–3), 107–118. [ Links ]

Engel, F. J, Blackwell, R. D, & Miniard, P. W. (1995). Consumer Behavior. New York: Dryden Press. [ Links ]

Finkelman, D. (1993). Crossing the Zone of Indifference. Marketing Management, 2(3), 22–32. [ Links ]

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to Theory and research. Boston: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

Florida Caribbean Cruise Association. Assessed May 28, 2015, www.f-cca.com. [ Links ]

Fornell, C. (1992). A national customer satisfaction barometer: the Swedish experience. Journal of Marketing, 56(1), 6–21. [ Links ]

Fyall, A., Callod, C. & Edwards, B. (2003). Relationship marketing, the challenge for destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 644–659. [ Links ]

Gabe, T., Lynch, C., & McConnon, J. (2006). Likelihood of cruise ship passenger return to a visited port: the case of Bar Harbor, Maine. Journal of Travel Research, 44(3), 281–287. [ Links ]

Gallarza, M. G., & Saura, I. G. (2006). Value dimensions, perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty: an investigation of university students travel. Tourism Management, 27(3), 437–452. [ Links ]

Gursoy, D., McCleary, K. W. & Lepsito, L. R. (2007). Propensity to complain: affects of personality and behavioral factors. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 31(3), 358-386. [ Links ]

Hallowell R. (1996). The relationship of customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, profitability: an empirical study. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 7(4), 27–42. [ Links ]

Holloway, C. (2002). The business of tourism harlow: Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times-Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Hosany, S. & Witham M. (2010). Dimension of cruisers experiences, satisfaction and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 351–364. [ Links ]

Howard, J. A., & Sheth, J. N. (1969). The Theory of Buyer Behavior. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [ Links ]

Jamal, A. (2004). Retail banking and customer behavior: a study of self-concept, satisfaction and technology usage. International Review of Retailing, Distribution and Consumer Research, 14(3), 357-79. [ Links ]

Johnson, G., Scholes, K., & Whittington, R. (2005). Exploring Corporate Strategy, 7th Edition. New Jersey: Prentice hall. [ Links ]

Kester, J. G. C. (2002). Cruise tourism. Tourism Economics, 9(3), 337–350. [ Links ]

Klein, R. (2005). Cruise ship squeeze: the new pirates of the seven seas. Canada: New Society Publisher. [ Links ]

Kleymann, B., & Seristö, H. (2004). Managing Strategic Airline Alliances. Aldershot: Ashgate publishing. [ Links ]

Kotler, P. (2000). Marketing Management. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Kotler, P. (2003). Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning, Implementation, Control. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Kozak, M. (2001). Repeaters behaviour at two distinct destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 28, 784–807. [ Links ]

Kozak, M. & Rimmington, M. (2000). Tourist satisfaction with Mallorca, Spain, as an off-season holiday destination. Journal of Travel Research, 38(1), 260–269. [ Links ]

Kuhl, J. & Beckmann, J. (Eds.) (1985). Action control from cognition to behavior. Heidelberg: Springer. [ Links ]

La Barbara, P.A., & Mazursky, D. (1983). A longitudinal assessment of consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction: the dynamic aspect of the cognitive process. Journal of Marketing Research, 20, 393–404. [ Links ]

Lee, C. K., Yoon, Y., & Lee, S. K. (2007). Investigating the relationships among perceived value, satisfaction, and recommendations: the case of the Korean DMZ. Tourism Management, 28(1), 204–214. [ Links ]

Lobo, A. C. (2008). Enhancing luxury cruise liner operators' competitive advantage: a study aimed at improving customer loyalty and future patronage. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 25(1), 1–12. [ Links ]

Mazursky, D. (1989). Past experience and future tourism decisions. Annals of Tourism Research, 16, 333–344. [ Links ]

McDougall, G. H. G., & Levesque, T. (2000). Customer satisfaction with services: putting perceived value into the equation. Journal of Service Marketing, 14(5), 392–410. [ Links ]

Mittal, V. & Kamakura, W. (2001). Satisfaction, repurchase intent, and repurchase behavior: investigating the moderating effects of customer characteristics. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(1), 131–42. [ Links ]

Monroe, K. B. (1990). In pricing: making profitable decisions. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Moscardo, G., Morrison, A., Cai, L., OLeary, J., & Nadkarni, N. (1996) Tourist perspectives on cruising: multidimensional scaling analysis of cruising and holiday types. Journal of Tourism Studies, 7(2), 54-64. [ Links ]

Nicholls, J. A. F., Gilbert, G. R., & Roslow, S. (1999). An exploratory comparison of customer service satisfaction in hospitality-oriented and sports-oriented businesses. Journal of Hospitality Leisure Marketing, 6(1), 3–22. [ Links ]

Oh, h. (1999). Service quality, customer satisfaction, and customer value: a holistic perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 18, 67–82. [ Links ]

Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(Special Issue), 33–44. [ Links ]

Parasuraman, A. (1997). Reflections on gaining competitive advantage through customer value, Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 25(2), 154–61. [ Links ]

Parasuraman, A., & Grewal, D. (2000). The impact of technology on the quality-value-loyalty chain: a research agenda. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 168–174. [ Links ]

Parasuraman, A., Berry, L. L. & Zeithaml, V. A. (1991). The nature and determinants of customer expectations of service. Working Paper, Marketing Science Institute. [ Links ]

Patterson, P. G., & Spreng, R. A. (1997). Modeling the relationship between perceived value, satisfaction and purchase intentions in a business-to-business, services context: an empirical examination. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 8(5), 414–434. [ Links ]

Petrick, J., Morais, D., & Norman, W. (2001). An examination of the determinants of entertainment vacationers intention to revisit. Journal of Travel Research, 40(1), 41–48. [ Links ]

Petrick, J. F. (2003). Measuring cruise passengers perceived value. Tourism. Analysis, 7(3/4), 251–258. [ Links ]

Article history:

Submitted: 30.08.2015

Received in revised form: 19.01.2016

Accepted: 20.01.2016