Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Tourism & Management Studies

Print version ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.12 no.1 Faro Mar. 2016

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2016.12115

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

The role of satisfaction in cultural activities word-of-mouth. A case study in the Picasso Museum of Málaga (Spain)

El papel de la satisfacción en las recomendaciones de actividades culturales. Estudio de un caso en el Museo Picasso de Málaga (España)

María Jesús Carrasco-Santos1, Antonio Padilla-Meléndez2

1Universidad de Málaga, Facultad de Turismo, Campus de Teatinos, 29071 Malaga, Spain. E-mail: mjcarrasco@uma.es

2Universidad de Málaga, Facultad de Estudios Sociales y del Trabajo, Campus de Teatinos, 29071 Malaga, Spain. E-mail: apm@uma.es

ABSTRACT

Word-of-mouth has become a relevant area of tourism research over recent decades. However, the effect of tourists emotions on these recommendations is an underdeveloped area, particularly in cultural tourism, which, in terms of tourist numbers, is the second most important sector in countries with significant tourism industries, such as Spain. Taking stock of recent advances in cultural tourism, this paper explores specific factors that can affect visitors recommendations of a museum, in this case the Picasso Museum in Málaga (Spain). In a novel approach, an experiment (involving a guided tour of some of Picassos shortlisted works and painting a self-portrait) was conducted with 127 first-time Picasso Museum visitors (52.8% Spaniards and 47.2 % international visitors). The results show that strengthening the activation of emotions in tourists and non-tourists during cultural activities has a positive effect on their satisfaction, thereby positively influencing their word-of-mouth about the museum.

Keywords: Cultural tourism, word-of-mouth, museums.

RESUMEN

El boca a boca se ha convertido en un área relevante de la investigación en la actividad turística en las últimas décadas. Sin embargo, los efectos en esta recomendación de las emociones de los turistas es un área poco desarrollada, sobre todo en el turismo cultural. Este turismo es el segundo sector más importante en términos de número de llegadas de turistas en los países con turismo significativo, como España. Haciendo un balance de los avances recientes en el turismo cultural, este artículo explora los factores específicos que pueden afectar a los visitantes para realizar recomendaciones después de haber realizado una visita a un museo, en este caso, el Museo Picasso de Málaga (España). Como un enfoque novedoso, se diseñó un experimento (una visita guiada por algunas obras preseleccionadas y la realización de un autorretrato), realizado con 127 personas que visitaron por primera vez el Museo Picasso, de los cuales el 52,8% eran españoles y el 47,2 restante eran turistas internacionales. Los resultados muestran que la activación de emociones en turistas y no turistas, cuando están realizando actividades culturales, tiene un efecto positive en su satisfacción, afectando esto positivamente a la recomendación del museo.

Palabras clave: Turismo cultural, word of mouth, museos..

1. Introduction

Interest in cultural tourism has increased in recent years as it can be considered a feasible way to rejuvenate a crowded tourist market and attracts tourists who have a greater propensity to spend money. This type of traveller is particularly interested in local products and cultural events that provide them with added value and are more independent, thereby helping to deseasonalise the destination (Figini & Vici, 2012). For example, in Spain in 2013, international tourists arriving for cultural reasons comprised 14% of the total number of tourists (Instituto de Estudios Turísticos, 2013) and 53.9% of all international tourists undertook some kind of cultural activity (Anuario de Estadísticas Culturales, 2014). In the same year, indicators of the total expenditure of international tourists during trips made mainly for cultural reasons amounted to 7462.1 million (EGATUR, 2013). In addition, it is important to note that, particularly in the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia, cultural heritage was highly valued, with 69.8% of tourists visiting monuments and museums.

Taking stock of the recent advances in cultural tourism literature and its relevance, this paper explores specific factors in museums that can affect word-of-mouth (WOM). In particular, the influences of pleasure, service quality, activation, and satisfaction are analysed. This is studied specifically in the context of cultural tourism and with first time visitors to the Picasso Museum in Málaga (Spain). The methodology involved developing a theoretical framework based on a summary of the literature and then conducting an experiment at the Picasso Museum to test the hypotheses. The results show that strengthening cultural activities has a positive effect on tourists propensity to recommend (WOM) as it leads to greater satisfaction and willingness to increase their WOM about the museum as well as the destination. Consequently, to conduct original cultural actions in the context of cultural tourism has a positive effect on the promotion of the destination itself, which leads to the conclusion that culture can be a relevant variable in promoting a destination if tourists have a good perception of service quality and experience the activation of their emotions.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. First, a review of the literature and the theoretical framework of the study are presented. The methodology and results of analysis are then summarised. A discussion of the results follows, before the final conclusions of the paper are outlined.

2. Theoretical framework

WOM is a complex phenomenon and generally not something that can be controlled directly, although numerous investigations show that WOM is one of the most influential channels of communication in the tourism market, with consumers more likely than those in other sectors to engage in it (Allsop, Bassett, & Hoskins, 2007). In the context of museums, visitor excitement could be considered a key factor influencing WOM (Blazevic et al., 2013). Therefore, museums should value the role WOM plays among its visitors, and in order to make these recommendations more powerful they should have profiles on social networks (Hausmann, 2012).

There are several studies about WOM and some of the variables that we used in our investigation. There are also recommendations on the importance of tourism destinations in maintaining a high level of satisfaction by offering services that make the most of the destination, as high satisfaction is an important factor in visitors engaging in positive WOM with potential visitors (Phillips, Wolfe, Hodur, & Leistritz, 2013).

2.1 Service quality

Several researchers have developed measures of service quality (SQ), relating the construct to variables such as expectation, quality, satisfaction, and customer attitude and behaviour (Boulding, Kalar, Staelin & Zeithaml, 1993). Customers of the tourism industry experience service with a number of interacting elements, such as provider environment, and customer (Reichheld & Sasser, 1990). What the consumer perceives is of vital importance to SQ and is a determinant of visitor satisfaction (Boulding et al., 1993; Camarero-Izquierdo, Garrido-Samaniego, & Silva-García, 2009; De Rojas & Camarero, 2008). The evaluation of service received can affect the customers satisfaction with the tourist destination visited either positively or negatively and it is therefore of great importance that their service experience is considered (Bitner, 1990).

Moreover, in the management of SQ, one of the cornerstones is consumer emotion (Zeithaml, Berry, & Parasuraman, 1996). Tourists experiences of and interactions with service providers will strongly influence their satisfaction. These experiences are defined as activities or a series of activities of a more or less tangible nature that occur between the client and employees of service providers and/or resources or physical goods and/or service provider systems, all of which are provided as solutions to the problems of the customer (Grönroos, 1984).

For Zeithaml et al. (1996), SQ, as well as retaining customers, has a direct influence on customer behaviour; high quality service may increase fair behaviour and future intentions and reduce adverse intentions. Cronin, Brady, and Hults (2000) study confirmed that service quality and customer satisfaction are directly related to behavioural intentions. Furthermore, Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (1988) created SERVQUAL, which measures quality of service, its antecedents and its consequences. Harrison-Walker (2001) measured SQ and the customer as the potential background for WOM engagement, noting that the quality of service has a positive impact on positive WOM. It would therefore be interesting to incorporate WOM as a promotional tool in marketing strategies. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

• H1: SQ and customer satisfaction are positively related.

• H2: SQ and pleasure are positively related.

• H3: SQ and activation are positively related.

2.2 Emotions: pleasure and arousal

The activation of emotions involves a complex set of interactions between subjective and objective factors, mediated by neural and hormonal systems, which can lead to affective experiences such as pleasure, disgust, or excitement, generating the effects of emotional perception and thus activating the behaviour of the consumer (Kleinginna & Kleinginna, 1981). In the study of consumer emotions, numerous contributions from the psychological field are of particular relevance. From a cognitive point of view, emotion is the result of interactions between the physiological and cognitive sectors of a person, assuming a change in trend or action as a response and complex reaction by the mind and body. This relates to mental states such as anger or anxiety and physiological responses, such as self-defence or a change in heart rate, which prepare people for action (Lazarus & Lazarus, 1994). The study of emotions in the discipline of marketing involves different models, but, following Bagozzi, Gopinath, and Nyer (1999), this paper focuses on the cognitive-affective component.

Focusing on the current state of emotion theories in the field of marketing, Huang (2001) undertook a comparison of theories in the psychological field and studies employing them in marketing research. The theories identified are as follows: differential emotions theory, the circular model of emotions, the pleasure, arousal and dominance (PAD) model, and the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). This research is based primarily on the PAD model, which consists of three dimensions: pleasure/displeasure, arousal/no excitement, and dominance/submission (Mehrabian & Russell, 1974). After studying this model, we decided to focus on two of the proposed dimensions: pleasure/displeasure and excitation/non excitation, described as the circumplex model of emotion developed by Russell (1980). This model holds that emotions are distributed in two dimensions: pleasure (pleasure/displeasure) and activation (excitation/non-excitation). Measurement scales in this model measure the pleasure a person feels about something and their arousal/excitement, rather than how active their emotions are. As for the application of this theory to the field of marketing, it has been successfully applied in the study of emotions during consumption (Mano & Oliver, 1993) and to study the emotional component of the consumption experience (Havlena & Holbrook, 1986).

In terms of the effects that emotions have on consumer behaviour, the interest lies in determining the effect on customer satisfaction. Nyer (1997) focused on the cognitive system of emotions, showing that the relevance of the objective (goal significance) and the desirability of the outcome (level of congruence) influence the consumers emotions and thus their behaviour, for example, leading to the consumer communicating via both positive and negative WOM. Although people may experience emotions privately, as in response to a physical hazard for example, emotions in the majority of cases are interpersonal or group responses to stimuli received (Bagozzi et al., 1999). As Camarero-Izquierdo et al. (2009) found in their study on the generation of emotions and satisfaction through cultural activities in museums, individuals feel more pleasure in group activities and experiences as opposed to experiences at an individual level. Interaction with other attendees and being with relatives (family or friends) also has a positive impact on the emotion experienced. On the other hand, other authors focus on the individual. They argue that tourism services must respond to consumer demand for services that enable individuals to create their own experience in a unique way, thus meeting individual needs and emotions, rather than considering group responses (Högström, Rosner, & Gustafsson, 2010). In terms of other features, it seems that factors such as the duration of the visit, prior knowledge of the subject or level of participation do not affect emotions (Camarero-Izquierdo et al., 2009). This paper takes into account these contributions, valuing the importance of the group in relation to emotions. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

• H4: Arousal and satisfaction are positively related.

• H5: Arousal and pleasure are positively related.

• H6: The dimension of pleasure and satisfaction are positively related.

2.3 Satisfaction

Consumer satisfaction is a central concept in modern thought and the practice of marketing and in todays competitive environment it is becoming increasingly important that the consumer is satisfied with the service provided (Lin, Chen, & Liu, 2003). The service tourists receive while on holiday will affect their level of satisfaction with the experience and subsequently their recommendation of the destination (WOM), in turn influencing sales. The importance of consumer satisfaction has led to a proliferation of research in this area, especially in recent decades. Tourist satisfaction is the index used to determine the level of liking, delight or displeasure experienced by tourists with respect to a particular destination.

Existing studies, however, differ with regard to the main concepts and their interrelationships. As such, due to the need for the integration of these studies, some authors have focused on providing a critical review of the research on consumer satisfaction. For example, Yi (1990) undertook a review focusing on three areas: (1) definition and measurement; (2) background or determinants; (3) consequences of consumer satisfaction. The author concluded that although satisfaction can generally be defined as a consumer response, there is a discrepancy between the standard of the product and the product as it perceived, making it necessary to go further and analyse satisfaction by linking it to customer experience. Satisfaction is based on the relationship between perceived risk and satisfaction (Yüksel & Yüksel, 2007) and is an emotional response that occurs as a result of the experience provided, for example, after shopping. Satisfaction is composed of affective and cognitive aspects and in relation to tourism, is influenced by the pleasure experienced during a visit (De Rojas & Camarero, 2008). Thus, satisfaction is an experiential construct with multiple attributes (Ryan, Shih Shuo, & Huan, 2010). Satisfaction can therefore be considered a result, but it can also be regarded as a process based on the perspective of the disconfirmation of expectations (Oliver, 1980) and the experience of consumption (Oliver, 1981).

In this study, the focus is on the cognitive and affective aspects of consumer satisfaction, in particular, the affective aspect of satisfaction which, together with emotions, humour and affection, form the emotional background that will impact satisfaction and in turn loyalty (Dick & Basu, 1994). In this regard, the work of Ladhari (2007) is of particular interest in exploring the effect of emotions on consumers satisfaction and subsequent behaviours. He summarised the types of emotions in the literature on satisfaction as follows: positive, negative, pleasant, surprise, excitement, guilt, etc. This study of Ladharis (2007) was based on the application of the pleasure/arousal (PA) model, in which emotions have two dimensions: pleasure and excitement. These two dimensions affect satisfaction, both potentially in a positive way. Ryan et al. (2010), whose study was carried out with reference to the determinants of satisfaction, agreed with Ladharis (2007) perspective and proposed a model in which the evaluation of satisfaction depends on the experience of the visit, preceded by the level of importance of attributes in motivating for the visit.

Furthermore, it is necessary to bear in mind that satisfaction in the tourism industry is highly influenced by the experiences tourists have of interacting with various service providers. Indeed, services are based on the experience and involvement of the consumer, necessitating the study of expectations and the effect of disconfirmation on satisfaction (Flint, Woodruff, & Gardial, 2002), as well as customers responses and preferences (Grigoroudis & Siskos, 2002). Satisfaction is a mental condition of the consumer (Oliver, 1980), based on emotions which are part of the central mechanism through which a sense translates into behaviour. Consequently, the following hypothesis can be proposed:

• H7: Satisfaction influences WOM.

3. Methodology

The sample was made up of 127 first time visitors to Picasso Museum. All participants were 19–27 years of age. Of the total participants, 52.8% were residents and non-residents in Málaga, Spain and 47.2% were international tourists. Idiomatic tourists visiting Málaga for college (47.2% of the sample) were chosen for the following reasons: (1) they were unfamiliar with the Málaga Picasso Museum; (2) the innovative experiment required active participation, so age was important. The researcher asked the international tourists which monument, museum or cultural site they intended to visit on arriving in Málaga, and the Picasso Museum was chosen first by the majority of respondents. In addition, the college students had never before been to the Picasso Museum, and were therefore first-time visitors. The age group of 19–27 was chosen because the museum attendance, according to the survey of cultural habits and practices from 2014/2015, indicated that of the 16,000 visitors attendance rates were higher among the younger group and declined with age. For this reason, we used a sample of younger people with high levels of education (Estadística de Museos y Colecciones Museográficas, 2014).

3.1 Research model

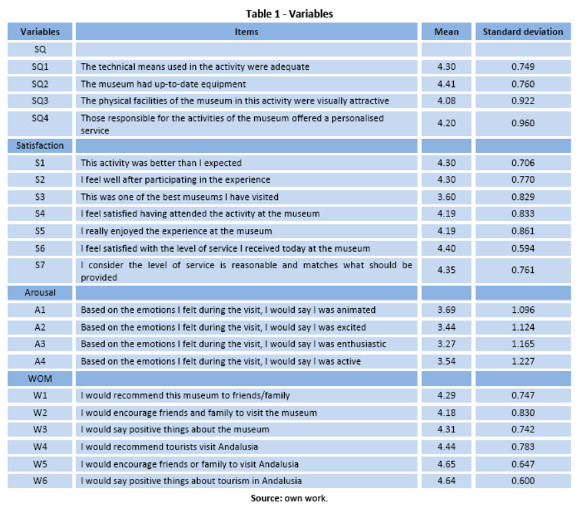

Of all the variables that can influence WOM following a cultural tourist experience, we focused on those of service quality (SQ), activation (ACT), pleasure (PL) and satisfaction (SAT). These variables were measured using a series of items in scales previously employed and validated by other authors and structured in a questionnaire (in English and Spanish). The responses were given on a five-point Likert scale which asked respondents to indicate their level of agreement with a series of statements. The results were then analysed to provide descriptive statistics (mean and dispersion, using the standard deviation).

3.2 Data collection

The research context was an experiment at the Málaga Picasso Museum. The Picasso Museum was selected because Picasso is an outstanding figure, both as an artist and as a man. He was an inimitable creator of various trends that revolutionised the art of the twentieth century, from Cubism to neo-figurative sculpture, from engraving and etching to craft ceramics, and designing the scenery for ballets. His work, vast in terms of number, variety and talent, stretched over more than 75 years, in which he combined painting with love, politics, friendship, and an exultant and contagious enjoyment of life.

Data collection took place over three days. In total, 127 participants completed the questionnaire, (64% women and 36% men). The 127 participants were divided into five groups of 21 students and one group of 22 students. The experiment consisted of an experiential visit to the museum followed by a self-portrait painting workshop titled And if you're the work? The experiment required the collaboration of a Picasso expert, an expert in art, and a professor of painting, all of whom could speak English. It began with a guided tour of the museum in groups (groups had a maximum of 22 members due to space constraints), where the guide explained nuances, shadows, colours, and feelings as well as presenting each era of Picassos works. Here the focus was on the points of view that Picasso invites the visitors to discover in his paintings, and intended to provide them with inspiration for their own creations.

The participants were then asked to paint a picture, specifically a self-portrait, taking into account what had been learned during the visit to the museum. They were encouraged to take digital photographs of themselves and from there, paint, distort or transform them, thus making their own portraits. A box was given to each participant containing a Picasso kit (canvas, a set of paints, and pencils) and a self-portrait of Picasso for the participants album collection. At the end of the activity, all participants received a gift folder with the materials used and their own portraits.

To enlist participants, we contacted the team of International Relations at the University of Málagaand, thanks to this collaboration, we could organise the visits in advance. All communication was done through personally contacting the participants via mail. To participate, visitors had to RSVP. The completion date was in May 2011. The Department of Education at the Picasso Museum facilitated the experiment; this department organises activities to increase participation around and knowledge of the works of Picasso, but this is not acknowledged as a marketing strategy for increasing positive WOM visits in their communication plan. Through meetings with the Museums board of education we performed a comprehensive analysis and measurement of the results of participants, then provided the Museum with the main data and findings of the study. As well as international tourists, we wanted to include residents and non-residents from Málaga in the sample of visitors, as long as they had never before visited the Picasso Museum. We wanted to keep the sample as close to the reality of the museums visitors as possible, which is why both residents and non-residents of Málaga and international visitors were included. The focus of the study was on knowing what variables trigger first-time visitors to engage in WOM and studying a different way to visit a museum which included active involvement and how a different, participatory experience relates to the activation of emotions when visiting a museum.

The main objective of the workshop was to evoke the sensations and emotions experienced during a museum visit in an active way, thus ensuring the involvement of the visitors and enhancing the positive consequences. In addition, the aim was to foster debate and respect for different points of view through a fluid dialogic approach within the groups. Through these means, it was intended to activate the emotions of the visitors.

Following the workshop, there was a debriefing session, which involved asking the participants whether they had imagined painting at the Picasso Museum and whether they considered painting in Picassos city to be the fulfilment of what might be a dream for some people. They were then asked to complete the questionnaire.

4. Data analysis and results

We analysed the data using the statistical program SPSS (23) to obtain descriptive statistics, then undertook path analysis using AMOS (23) to test the relationships proposed in the model. Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for the questionnaire items.

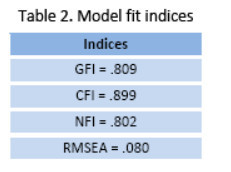

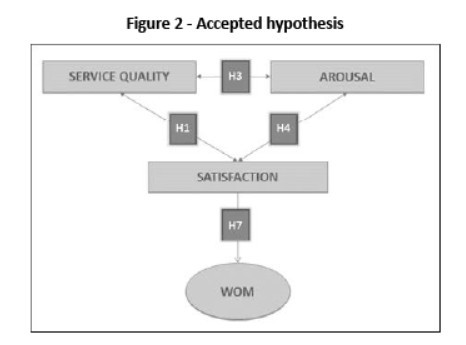

Exploratory factor analysis was undertaken. The reliability of the instrument was tested using Cronbachs alpha, taking the lowest limit considered valid as greater than 0.6. All variables obtained a Cronbachs alpha coefficient higher than 0.7, thus demonstrating very good consistency of the scale (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 2004). In order to test the relationships between the variables a structural equation modelling technique, using the software AMOS (23), was used. The goodness of fit reached the acceptable minimum levels (see Table 2). Only H1, H3, H4 and H7 were accepted (see Figure 1 and 2).

5. Discussion

In this paper, empirical research was conducted in a famous museum in an established destination. Taking stock of previous research, a theoretical framework around WOM and empirical research was defined. Four hypotheses have been confirmed. Consequently, adequate SQ and customer satisfaction are positively related (H1), as are SQ and activation (H3) and activation and satisfaction (H4). Furthermore, satisfaction influences WOM (H7).

From the relationships in the model, the analysis shows that quality of service and satisfaction are related. This is similar to previous findings that SQ has a positive influence on satisfaction (Baker & Crompton, 2000; Bigné, Sanchez, & Sanchez, 2001; Cole & Scott, 2004; Luarn & Lin, 2003; Osman,Cole & Vessel, 2006). Furthermore, in the case of museums, SQ appears to be a relevant factor for satisfaction, as found by Camarero-Izquierdo et al. (2009).

Concerning H3, it has been confirmed that there is a positive relationship between SQ and activation/arousal. Similar to Camarero-Izquierdo et al.s (2009) findings, it was found that individuals activate their emotions when involved in well-organised activities in groups. In addition, the experiment also included individual activities (reflection, painting) and highlights the need to provide visitors with opportunities to create their own experiences in a unique way, thus meeting individual needs and emotions, as found by Högström et al. (2010).

H4, which suggests that arousal and satisfaction are related, is also supported by the data. The activation of emotional dimensions has a direct, positive effect on satisfaction, as evidenced in the literature (Bigné & Andreu, 2004; De Rojas & Camarero, 2008; Erevelles, 1998; Westbrook & Oliver, 1991). Bigné and Andreu (2004) argued that any factor that improves the emotional state of the consumer during consumption may indirectly increase their satisfaction, which highlights the need to improve their affective state during the service encounter.

There are potential ways of increasing the affective impact on the consumer during the service experience. Affective aspects have a considerable impact on satisfaction in the early stages of the development process (De Rojas & Camarero, 2008).

In terms of satisfaction and WOM, H7 is supported. Satisfaction is a direct antecedent of WOM, as found by Mazzarol, Sweeney, and Soutar (2007), for example, the greater the satisfaction the more the client will be prepared to engage in positive communication regarding the experience. It is essential to ensure that the client leaves satisfied, as the WOM effect is extremely important for the acquisition of new customers. This finding is in line with the literature (Govers, Go, & Kumar, 2007; Ladhari, 2007). Whilst satisfaction regarding the quality of service has a positive impact on future behaviour, such as loyalty or talking to others (Walsh, Evanschitzky, & Wunderlich, 2008), it is important to bear in mind that customers may need to be educated to stimulate positive WOM (Bansal & Voyer, 2000). Moreover, thanks to the ties that develop between the companies and the consumer, greater satisfaction results in commitment to and identification with the company; ultimately, this leads to positive WOM (Chung & Tsai, 2009).

Tourist satisfaction supposes an increase in the number of tourists returning to the destination and the number of recommendations promoting the development of certain tourist areas (Söderlund, 1998). Feelings of satisfaction not only have a positive impact in terms of increasing recommendations, but also exert a positive influence on the seller, in this case the service provider, as through the various forms of post-service communication, important direct to the client communication is established (Swan & Oliver, 1989).

In summary, SQ, arousal and satisfaction are found to be correlated. Furthermore, they are indirect antecedents of WOM through satisfaction. Finally, customer satisfaction has a direct influence on WOM.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, an experiment in a museum, grounded in a theoretical framework around WOM, has been described and its results analysed. The main findings relate to how the active participation of international tourists and non-tourists in an innovative initiative had a positive impact on evoking emotions among the groups. In addition, the results show that service quality is not enough; strengthening the activation of emotions in participants when they were involved in the cultural activity had a positive effect on their satisfaction, in turn positively affecting WOM about the Picasso Museum in first point and the Andalusia region in general. Consequently, participation in unfamiliar activities and the attendees being surprised increases satisfaction, thus leading to increased potential for positive WOM. Accordingly, the personal experience of participating in a project in which emotions are activated gives the participant a special interest in recommending such experiences through WOM. As a new contribution to existing understandings, it has been found that in the context of cultural tourism, and museum visits in particular, quality of service, activation of emotions, and satisfaction are related. Furthermore, customer satisfaction is the main antecedent of WOM. Consequently, in future models of customer satisfaction, emotions should be considered.

Some implications of this paper can be summarised. Firstly, in our study, the innovative experiment influenced the satisfaction of visitors. Determining the variables that have an impact on WOM means that providers can activate them through projects aimed at a particular target audience. Each visitor has an experience in relation to a particular service and this experience will involve emotions related to the received service. As a consequence, service providers should explore the stimulation of emotion in order to maximize consumer satisfaction. Here, it is necessary to raise awareness in museum managers and all those who interact with tourists and visitors, as these interactions are essential for evoking the emotions of the visitor. Communication regarding tourist destinations must take into account the emotions that customers perceive they will experience and they must then provide them during the tourists visit.

As recommendations, the relevance of WOM is justified as a consideration in the strategic plan of a museum. The factors found to affect the visitors recommendations of the museum should be considered and it is important to measure the visitors satisfaction with these types of experiences.

Secondly, for cultural tourists who interact with the destination and have a good experience of the service provider, SQ and WOM can be improved. Consequently, the companies that generate more positive WOM are those that will gain competitive advantage, thereby having a positive effect on the destination where they are located. In this case, tourist destinations should identify what differentiates them from other destinations in terms of cultural tourism and innovative cultural activities. The elements that induce positive emotions should be taken into account by public administrators responsible for the management of cultural tourist services.

As limitations, firstly, the sample selection could be improved, as an increase in the sample size would increase the generalisability of the results. Secondly, adding new variables to the analysis would be of benefit for the model, for example, including images of the destination, communication, and loyalty.

References

Allsop, D. T., Bassett, B. R., & Hoskins, J. A. (2007). Word-of-mouth research: principles and applications. Journal of Advertising Research, 47(4), 398. [ Links ]

Anuario de Estadísticas Culturales (2014). Estadísticas Culturales. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Available online (22/7/2015): http://www.mecd.gob.es/servicios-al-ciudadano-mecd/estadisticas/cultura/mc/naec/portada.html [ Links ]

Bagozzi, R. P., Gopinath, M., & Nyer, P. U. (1999). The role of emotions in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(2), 184-206. [ Links ]

Baker, D. A., & Crompton, J. L. (2000). Quality, satisfaction and behavioural intentions. Annals of Tourism Research,27(3), 785-804. [ Links ]

Bansal, H. S., & Voyer, P. A. (2000). Word-of-mouth processes within a services purchase decision context. Journal of Service Research, 3(2), 166-177. [ Links ]

Bigné, J. E., & Andreu, L. (2004). Emotions in segmentation: An empirical study. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 682-696. [ Links ]

Westbrook, R. A., & Oliver, R. L. (1991). The dimensionality of consumption emotion patterns and consumer satisfaction. The Journal of Consumer Research, 18(1), pp. 84-91. [ Links ]

Yi, Y. (1990). A critical review of consumer satisfaction.Review of Marketing, 4(1), 68-123. [ Links ]

Yüksel, A., & Yüksel, F. (2007). Shopping risk perceptions: Effects on tourists emotions, satisfaction and expressed loyalty intentions. Tourism Management, 28(3), 703-713. [ Links ]

Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioural consequences of service quality.The Journal of Marketing, 31-46. [ Links ]

Article history:

Submitted: 24.10.2015

Received in revised form: 06.12.2015

Accepted: 07.01.2016