Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.12 no.1 Faro mar. 2016

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2016.12119

MANAGEMENT: SCIENTIFICPAPERS

To what extent does human capital diversity moderate the relationship between HRM practices and organizational performance: Evidence from Spanish firms

En qué medida la diversidad de capital humano modera la relación entre las prácticas de GRH y el rendimiento organizacional: Evidencia de las empresas españolas

Rafael Triguero-Sánchez1, Jesús C. Peña-Vinces2, Mercedes Sánchez-Apellániz3

1University of Seville, School of Economics and Business, Department of Business Administration and Marketing, 41018, Sevilla, Spain. E-mail: rtriguero@us.es

2University of Seville, School of Economics and Business, Department of Business Administration and Marketing, Avenida Ramón y Cajal nº 1, 41018, Sevilla, Spain. E-mail:jesuspvinces@us.es

3University of Seville, School of Economics and Business, Department of Business Administration and Marketing, 41018, Sevilla, Spain. E-mail: apellaniz@us.es

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this research study is to explore the moderating effect the diversity of human capital may have on the relationship between HRM practices and business performance. To this end, factors determining of human capital diversity have been used.

With a sample of more than one hundred Spanish companies we have carried out a factor analysis-principal axis factoring with varimax rotation- on identified HRM practices and perceived organizational performance as factors with good factor loadings, and consistent with the proposed model.

Our findings indicate that the human capital factors such as education level," functional specialization and length of service condition the effects of HRM-practices on organizational performance.

The literature pays little attention to non-linear models. Examining the factors' determining human capital diversity casts some light on the black box of the relationship between human resources practices and organizational performance.

Keywords:Employee diversity, human capital, HRM practices, organizational performance, Spanish firms.

RESUMEN

El propósito de este estudio de investigación es explorar el efecto moderador que puede tener la diversidad de capital humano sobre la relación entre las prácticas de Gestión de Recursos Humanos (GRH) y rendimiento de la empresa. Para alcanzar este objetivo, se han utilizado los factores determinantes de la diversidad del capital humano. Con una muestra de más de 100 de empresas españolas y un análisis factorial con una rotación varimax, hemos evaluado las prácticas de GRH y el desempeño organizacional percibido. Dichas variables han mostrado buenas cargas factoriales, en consonancia con el modelo propuesto.

Nuestras conclusiones indican que los factores de capital humano tales como: el nivel educativo, la especialización funcional y la antigüedad en el puesto, condicionan los efectos de las prácticas de GRH y el desempeño organizacional.

El estudio de la relación práctica de GRH- desempeño organizacional y la evaluación de los factores que determinan la diversidad del capital humano nos arroja algo de luz sobre la llamada caja negra. Debido a que, la literatura presta poca atención a los modelos no lineales.

Palabras clave: Diversidad de los empleados, capital humano, prácticas de GRH, rendimiento organizacional, empresas españolas.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing interest among researchers on the effect of employee diversity on organizational performance (Jackson, Joshi & Erhardt, 2003; Van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007). Jackson et al.(2003) have noted that although research studies analyzing the impact of diversity on performance are based on a clearly structured set of theoretical approaches; one of their weaknesses is that only a few of them do analyze how diversity affects performance.

Diversity refers to the differences among individuals based on any attribute that may lead to a perception that someone is different from oneself (Williams & OReilly, 1998) or among interdependent members of a work unit (Jackson et al., 2003). Attributes of interest may be those that are quickly detected when we meet someone for the first time (demographic attributed such as age, gender or ethnicity); other underlying less perceivable attributes, only become apparent when we get to know an individual (personality, knowledge, values); and there are other ones which are found between these two extremes of transparency (such as education level or professional experience), which are known as human capital due to their relationship to professional knowledge, skills and know-how (Becker, 1964; Triguero-Sánchez, Peña-Vinces & Sánchez-Apellániz, 2011).

According to Van Knippenberg and Schippers (2007), the dissimilar findings we can find in this research field could lead us to assume that the prevailing research studies in this field have focused on the main effects," such as compromise, satisfaction, testing relations between different dimensions of diversity and outcomes, neglecting potentially moderating variables. Although the moderating nature of some variables of the relation between diversity and performance has been analyzed, as it is the case with leadership or with team experience over time (Harrison, Price, Gavin & Florey, 2002), few research studies have considered diversity as a moderating variable between Human Resources (HR) policies and practices and corporate performance. This study aims to fill this research gap. Consequently, the objective of this research is to analyse the moderating effect that employee diversity has in the relationship between HR policies focusing on commitment and organizational performance.

Moreover, more than half of Spanish firms follow an isomorphic approach; in other words, these companies tend to imitate or copy the practices (HRM practices) of other businesses but in fact, they are not aware of how employee diversity affects their organizational performance. In this sense, our investigation is presented as an alternative to this problem.

Future research will benefit from the role of diversity as a moderating element in HR management (HRM) and of how it can contribute to business success contributing to the strengthening of the Resource-Based View, according to which HR is a source of competitive advantage.

2. Research model and construct definitions.

2.1 High commitment HRM practices

Since the 1990s, it is possible to find in the literature a growing interest for HRM and in particular, for the relationship between HRM and performance (Guest, 1997; 2011). The literature suggests that Human Resources (HR) practices are directly and indirectly linked to the collective behavior of employees, that they may have an impact on them and their attitudes (Al-Jabari, 2013), which in turn can serve as mediators between such practices and corporate performance.

Concerning the orientation of HR practices, Walton (1985) indicates the need to change from control practices to commitment practices as the basis for managing the work of individuals. For this author, there is no choice; he prescribes a commitment strategy if we intend to prosper. The idea that elevated commitment HR management practices have an impact on attitudes towards work through employee perception or through their experiences is supported by the Social Exchange Theory (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005), and the signaling theory (Ostroff & Bowen, 2000). These theories propose that high commitment HR practices have an impact on employees because they support them; they work as signs of the intentions of the organization towards them.

2.2 Perceived organizational performance and its relationship to HRM practices

There are multiple research studies that have addressed the relationship existing between HR management and organizational performance (OP) as well as their measurement (Barrena-Martínez, López-Fernández & Romero-Fernández, 2013). However, there is no clear consensus on how to measure it (Guest, 2011). Guest (1997) has raised doubts about the cause-effect relationship between HRM as input and results based on financial performance. Despite of the attractive of using economic indicators in any attempt to convince top managers of the impact of HRM, we need to use a wider range of measures if we want to understand how and why HRM has an impact on financial performance(Guest, 1997: 274).

The use of more closely-related indicators, especially those on which the workforce may have an impact are theoretically more plausible (since HRM aims at improving the direct contribution of employees to performance) and methodologically they are easier to relate. We need performance indicators that are much closer in terms that they indeed affect HRM practices. In this line, there is a clear option for the use of non-financial measures when analyzing effectiveness of HRM practices (Bontis, Crossan & Hulland, 2002; Triguero-Sánchez, Peña-Vinces, González-Rendón & Sánchez-Apellániz, 2012).

An important mechanism that has been proposed suggests that the impact of HR practices on performance takes place through individual employees (Neves, Galvão & Pereira, 2013). Some authors emphasize the crucial role of employee attitudes and behaviors to translate HR practices to firm performance. In line with this more central role of employees, these authors emphasize the need of including employee perceptions in HR research studies (Guest, 2011).

Guest (2011) says that the models originating in organizational and social psychology make us reflect on the fact that what is actually important is not the presence of HR practices, but rather the perception of the intention underlying such practices. The way in which practices are interpreted can shape the response to them.

In HR strategic management research perceptions on corporate performance of the HR department or of managers have been frequently used as performance indicators being considered as a reasonable substitute for objective performance measures (Den Hartog, Boon, Verburg & Croon, 2013). Measurement of perceived organizational performance refers to important aspects such as product quality, client satisfaction and development of new products. In the same line Den Hartog et al. (2013) have established that the existing measures for sensed perceived organizational performance generally cover different performance aspects, adding to product quality or client service and satisfaction other aspects related to reputation. In this research study and according to Bontis et al.(2002) the items used to measure the perceived performance measures construct include the classification of the future perspectives of the business, meeting clients needs and global assessment of business performance.

In this research study, we expect HR practices focusing on commitment to correlate positively with perceived organizational performance measures – global assessment of business performance, meeting clients needs, future perspective of the company and reputation. It is expected that commitment-oriented practices will encourage employee participation in decision-making in their group, search for agreements among them and prevention of interpersonal conflicts (Bowen & Ostroff, 2004). This is likely to favor greater employee integration and the development of positive attitudes and behaviors towards the organization. Such integration and behaviors are expected to be associated to higher-performance levels (Den Hartog et al., 2013). Therefore, we expect perceived organizational performance to be higher where commitment-oriented HRM practices are implemented.

2.3 Employee diversity as moderating variable

Although the literature suggests that there is a relationship between HR practices and organizational performance, there are still open questions on how this relation takes place, on which are the variables existing in the black box". Therefore, there is a need for further research studies considering factors that may intervene and/or moderate the relation between HR practices and organizational performance. According to Guest (2011), the commitment level developed by employees in response to HR practices cannot be homogeneous. The changing values of the workforce, the generation they belong to, their work experience and their varying personal circumstances may alter their priorities. The values and reasons of employees and the differences among them must be taken into account in research of HRM and performance.

Research on workforce diversity has focused on two main aspects: demographic diversity and human capital diversity. Organizational demography diversity researchers focus mainly on characteristics that are visible such as age, or gender, or on attributes related to work, such as functional experience. The theory most frequently followed by diversityresearchers states that variations in the composition of work groups or teams affects group processes, and this process has an impact on performance (Williams & OReilly, 1998). This approach relies on the knowledge-based view and the decision-making perspective, also called Cognitive Resource Theory (Woehr, Arciniega & Poling, 2013); it defends that diverse values in employees will contribute to a better firm performance. Positive effects on performance are achieved when organizations adapt their management practices to the characteristics of their workforce, thus improving management and performance (Benschop, 2001). However, based on the literature reviewed, in our study, we have focused our attention on human capital diversity (education level, functional specialization, length of service and tenure). We use these factors to establish the moderating effect of employee diversity on the relationship between HR policies focusing on commitment and organizational performance. The main reason as we mentioned in the introduction is that we have not found any research study that has used these factors as moderator variables.

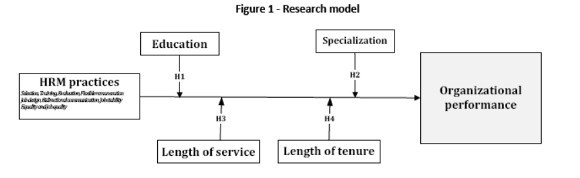

Therefore, in Figure 1, we summarize the theoretical background and research model of the literature to be analyzed.

2.4 Hypotheses

2.4.1 Education level

The concept of education level refers to formal education, including primary, secondary and higher education. This is one of the indicators that has been most frequently used to measure human capital based on the academic level completed. We can expect educational diversity to be associated positively to group performance, although this impact may not be as direct as it could be initially expected, since it may indicate distinct education levels or different educational experiences (Williams & OReilly, 1998). Some research studies suggest that educational heterogeneity is associated to taller company growth rates and to strategic initiatives. Dongfeng (2013) finds and verifies that higher-education diversity bring on higher conflict levels as well as better team performance, since the greater the educational differences, the easier it will be to encourage useful discussion leading to an improvement of employee performance.

Educational differences affect the way in which information and its sources are accessed, perceived and analyzed; this will influence decision-making, and the way individuals perceive the reality around them. Therefore, it is likely that the greater the educational heterogeneity, the more different the perceptions of employees and, as a consequence, the more different their contribution to work groups will be. This circumstance may have an impact on the relationship between HRMp and OP.

Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

• H1: Education level diversity will moderate the relationship between HRM practices and OP.

2.4.2 Functional specialization

The term specialization refers to the work background of an individual in an organization, such as finances, operations, sales From this perspective it is considered that the division of labor in an organization leads to a certain groupings of tasks, and therefore, of knowledge associated to the functional departments in which employees have gained their experience. Thus, specialization level provides us with a useful and easily-accessible indicator of the experience gained by individuals, and consequently, of the team in which they collaborate (Bunderson, 2003). The relationship between individuals with different functional backgrounds in an organization will impact on their decisions, involvement, etc. especially in the case of multifunctional teams. Some laboratory and field studies have found that functional diversity has a positive impact on employee performance (Williams and OReilly, 1998). Consequently, from a certain level of specialization on, conflict levels among work team members may increase, hindering internal communication and coordination among its members (Jehn and Bezrukova, 2004). Although research studies have shown the presence of effects between functional specialization diversity and performance, some results may be contradictory.

Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

• H2: Functional specialization diversity will moderate the relationship between HRM practices and OP.

2.4.3 Length of service and tenure diversity

This concept refers to the time an employee has been working in an organization, and it has been used in previous research studies (Perreti and Negro, 2007). Length of service has been associated to how familiar employees are with the policies, procedures and other circumstance of the positions, teams and departments of the organizations for which they work or have worked. Members have got different views of their organization and of its processes. Employees with shorter times of service are more flexible, but they tend to be critical towards existing processes, and this may generate conflicts among employees. Additionally, it is not infrequent that they are stereotyped and/or excluded by more veteran employees (Perreti and Negro, 2007).

Lampel, Shamsie & Lant (2006) say that the success of this type of diversity will depend on the combination of values shared by the organization. Where there is little difference in employee length of service, there are fewer interruptions in communication and fewer task conflicts, as a result of the presence of codes, rules and values that are commonly known to work team members. High disparity among members has been related to low levels of group cohesion, greater use of formal communication, as well as higher creativity levels in research activities.

Some research studies suggest that length of service diversity has a positive impact on performance (Harrison et al., 2002). This argument has been supported by Williams and OReilly (1998), who argue that there will be a positive relation, provided that organizations take into account any negative effects resulting from diversity. They also suggest that a greater diversity in tenure may have an impact on the outcomes expected from the different actions and HRM practices. However, they do not state whether length of service at the company and tenure have the same effects.

From this perspective, we propose the following hypothesis:

• H3: Length of service diversity will moderate the relationship between HRM practices and OP.

• H4: Tenure diversity will moderate the relationship between HRM practices and OP.

3. Methodology

3.1 Population and sample

The questionnaire methodology was adopted in research study on human resources management. Concerning the sample, the questionnaires have been answered by HR managers, HR general managers and general managers.

Although the general standard in HR research is to use one single informant in each company due to the difficulty of obtaining multiple informants, in fact, we recognize the possibility of single-method bias in our data. Consequently, we increase the confidence in our data by: (1) undertaking a factor analysis which showed the absence of a single general factor to account for most of the covariances in our variables, indicating the absence of common method variance problems for our data; (2) personally identifying qualified respondents (e.g. HRM managers). Previous literature has shown that the views of a single but well-qualified informant may better capture a firms behavior as compared to the views of several respondents in the case of organizations where relevant decisions are often highly centralized (Triguero-Sánchez et al., 2012).

The selected people in each company were contacted by telephone. They were explained the importance of taking part in the study and also its usefulness. Where required, we make the commitment to send them the outcomes of our research study. They were also assured that all information would be treated in a confidential, comprehensive and anonymous manner. Finally, we highlighted the importance of any suggestions the interviewees may propose to us, and our gratitude for their participation. All of these aspects were emphasized in the introductory letter which was subsequently sent along with the questionnaire and a prepaid envelope for returning upon completion.

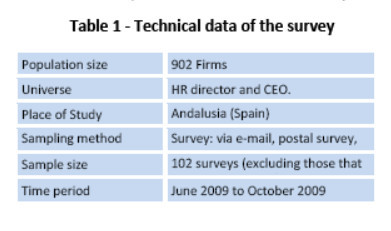

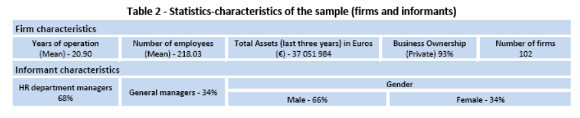

The companies were selected from the SABI database (Iberian Balances Analysis System). Among the registered companies, 1300 had between 100 and 2000 employees, according to the data registered in 2007, and 1169 had been established before 2003. The resulting population was 902 with a well-balanced representation of all productive sectors. A total of 103 questionnaires were returned in different forms: via e-mail, postal mail, and personal interviews at their organizations. This represents a response of 11.42%. With regard to the nature of companies, 93% of them belong to the private sector and the remaining, to the public sector, in other words; they belong to the Spanish government. The following tables (Table 1 and 2) summarize the descriptive statistics of the unit analysis.

3.2 Measurement of variables

A literature review was carried out in order to obtain a reliable measurement scale, using tools broadly validated and contrasted in previous research studies. The items adapted from the English literature were translated from English into Spanish by two native Spanish speakers who are familiar with the HRM terminology in order to prevent any ambiguity in measurement scales.

3.2.1 Organizational performance

To measure subjective, or perceived, organizational performance, a reduced version of the measurement scale developed by Bontis et al. (2002) to evaluate organizations as a whole was used. This scale comprises only four items. One example of the items used is: our organization is well-respected within the industry. Cronbach´s Alpha (CA) coefficient for the scale was 0.878, its Composite Reliability (CR) = 0.865 and its Average Variance Extracted (AVE) = 0.617.

3.2.2 HRM practices

The variables used to measure HRM practices are supported by the existing literature. We have used the measuring items developed by Triguero-Sánchez et al. (2012), confirmed for the Spanish case, with a 1-7, 38-item Likert-type scale. As we expected all the items in the scale loaded on a single factor using Principal Component Analysis. These items had a CA of a 0.960 and a CR = 0.951 and an AVE= 0.654. In the scale, 1 indicates high control and low commitment to the organization, and 7 indicates high commitment and low control. For this variable, aspects such as personnel selection, training, evaluation, wage flexibility, job design, communication level, job stability, equal opportunities and the quality of human resources management have been measured.

3.2.3 Diversity factors

Constructs such as Level of Education (4 items), Level of Specialization (5 items), Length of Service within the organization (2 items) and Tenure (2 items) were evaluated (see Triguero-Sánchez et al., 2011).

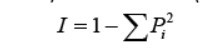

The four factors of diversity were incorporated into the model by means of Blaus index of heterogeneity, which is broadlyaccepted in social and behavioral sciences. The next expression (Formula 1) shows Blaus index (1977).

(I) = Blaus index

(P) Is the proportion of people in each category studied and

(i) The number of categories observed

[It must be mentioned that we were asking for the approximate percentage in each category].

In other to get a parsimonious model, once that the Blaus index was obtained for each factor of diversity, they were transformed into 7-point Likert scale where: 1 = low heterogeneity, 7 = high heterogeneity.

4. Data analysis and results

First, we analyzed factor structure and reliability of all scales using PASW Statistics 18 software (IBM SPSS Software, 2009). Factor analysis and scale reliability procedures within the PASW Statistics 18 software were carried out to assess the dimensionality and internal homogeneity of the scales. The exploratory factor analysis (principal axis factoring with varimax rotation) identified HRM practices and perceived organizational performance as factors with good factor loadings, which was consistent with the model we proposed. As described in the Criterion variables and Predictor variables sections, the reliabilities for all the constructs exceeded Nunnallys (1978) recommended level of 0.70. Second, following Dawsons (2013) recommendations, we created the mean-centering (i.e., subtracting the mean from the value of the original variable so that it has a mean of 0) for the HRM practices and organizational performance constructs. This procedure ensures that the (unstandardized) regression coefficients of the main effects can be interpreted directly in terms of the original variables. It is important to mention that there are other alternative processes. However, as Dawson (2013) states, such procedures lead to identical results. Finally, we have carried out the moderated regression analyses using an online resource (http://www.afhayes.com/index.html).

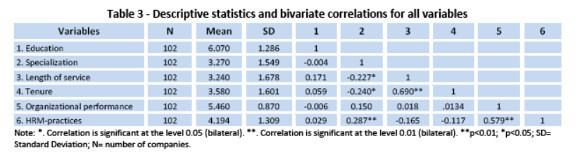

Diversity in the length of service is positively correlated to tenure(p=0.690**), which could be understood that when organizations coexist employees, with different antiques, diversities also exist in the length of the jobs (see Table 3).

However, there is a negative correlation between functional diversity and tenure (p=-0.240*), and also between functional diversity and length of service diversity (p=-0.227*). This means that in companies with fewer functional areas in their structure there is a trend of higher employee mobility between the different areas or functions, which could enhance their polyvalence. Moreover, we could deduce that as companies have more polyvalent structures they also have more flexible HR structures in place, in terms of both functional mobility and enrolment rates, resulting a more balanced workforce in terms of new employees and permanent employees. Education level diversity does not correlate to any of the other human capital variables.

Regarding the dependent variable, our data show that there is no significant correlation to the other variables in the study, except for HRMp (p=0.579**) which strengthens our econometric model and confirms the results found in the literature review. Moreover, HRMp seem to be correlated to functional diversity (p=0.287**). This indicates the importance of the functional composition of the working groups in HR policy and management.

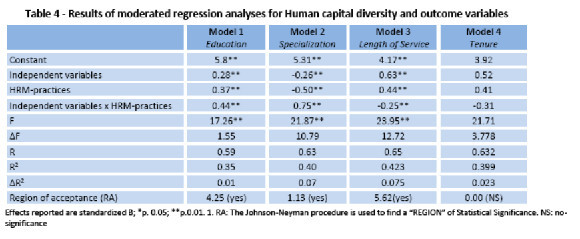

The moderating effects of the variables under study have been shown for human capital diversity variables: moderating effects for education (B=0.28**; RA=4.25), functional specialization (B=-0.26***; RA=1.13) and length of service (B=0.63***; RA=5.62), whereas tenure has shown no moderating effect (b=0.52; RA=0.00).

5. Discussion, conclusions and implications

Among the four human capital variables potentially moderating the HRM practices-OP relation, only one of them has not achieved enough statistical significance to be confirmed as such (tenure). This would be in line with Pelleds (1996) position, since he declares that human capital indicators have a strong relation with performance.

Model 1 (Table 4) confirms hypothesis H1 since it shows that education diversity is a conditioning factor of the HRM practices-OP relation; indeed, if we analyze overall results this is one of the variables most strongly conditioning such relation (ß=0.28**; RA=4.25), and it does so directly; i.ethe more heterogeneous education levels are the better factors to get a great organizational performance which is achieved when HR policies focusing on commitment. This is in line with the findings of Wieserma and Bantel (1992) showing that greater education heterogeneity is associated to higher corporate growth rates.

Model 2 indicates that the moderating variable work specialization conditions the HRM practices-OP relation although with lower intensity than the variable education (ß=-0.26***RA= 1.13). In this case, our findings suggest that the more homogeneous functional specialization levels are, the better result will be achieved by commitment-focused HR practices, which confirms the hypothesis H2. In this case, our findings are in line with those of Jehn and Bezrukova (2004), who consider that beyond a certain level of specialization the intensity of conflicts between work team members may increase, making internal communication and coordination among individuals more complex. Thus, better results are achieved with lower levels of functional specialization, something that could be explained by the current demand for organizations with a high polyvalence.

According to the results shown in Model 3, the most important diversity variable in terms of conditioning the HRM practices-OP relation is length of service (ß=0.63; RA=5.62), which leads

us to accept hypothesis H3. Thus, diversity in length of service with the company provides the best outcomes in the application of HR practices focusing on commitment. This may be due, as Williams and OReilly (1998) have suggested, to the fact that this heterogeneity provides an information diversity that enhances group performance, or that in the companies under study, heterogeneity in length of service is not associated to emotional conflicts, since there is a set of values shared by all members of the organization (Lampel et al., 2006).

Finally, the results of Model 4 on diversity in tenure lead us to reject hypothesis H4 since its values are out of the acceptation region of a model with a moderating effect (ß=0.52; RA=0.00). This allows us to conclude that differences in length of tenure among employees are not a determinant factor in organizational performance as far as implementation of commitment-focused HR practices is concerned.

In conclusion, we have found that the indicators related to human capital provide a strong moderating effect in the relation between HR practices and organizational performance, as already anticipated by Woehr et al.(2003) and in line with Pelled (1996); these indicators are functional specialization, length of service and education.

The results of this study have a number of important implications for future practice. The best results in the application of human-resource policies that focus on commitment are achieved when there is a variety in length of service. Companies must consider that a large diversity in the specialization level of their employees may make it difficult to adapt to changes and hinder organizational performance. As perceived by their managers, a higher diversity in length of service with the company and a higher diversity in education levels will contribute to business success since they can rely on a workforce committed to an organization in which they can develop a professional career.

A limitation of the study is that we must be cautious with its findings since the study has focused on a specific region with its own particular culture. Likewise, it would be interesting to dwell further into each of the HR practices in order to know more accurately their actual contribution to the model.

References

Al-Jabari, M. (2013). Factors affecting human resource practices in a sample of diversified Palestinian organizations. In José António C. Santos, Filipa Perdigão & Paulo Águas (Eds.) Book of Proceedings – Tourism and Management Studies International Conference Algarve 2012, vol.2(pp. 587-593). Faro: University of the Algarve. [ Links ]

Barrena-Martínez, J., López-Fernández, M. & Romero-Fernández, P.M. (2013). Towards the seeking of HRM policies with a socially responsible orientation: a comparative analysis between Ibex-35 firms and Fortunes top 50 most admired companies. In José António C. Santos, Filipa Perdigão & Paulo Águas (Eds.) Book of Proceedings – Tourism and Management Studies International Conference Algarve 2012, vol.2(pp. 488-501). Faro: University of the Algarve. [ Links ]

Becker, B. (1964). Human Capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research. [ Links ]

Neves, C., Galvão, A. & Pereira, F. (2013). Guidelines in Human Resources Management. In José António C. Santos, Filipa Perdigão & Paulo Águas (Eds.) Book of Proceedings – Tourism and Management Studies International Conference Algarve 2012, vol.2(pp. 420-429). Faro: University of the Algarve. [ Links ]

Nunnally, J. (1978), Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Ostroff, C., & Bowen, D.E. (2000). Moving HR to a higher level: HR practices and organizational effectiveness. In Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.W.J. (Eds.) Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp.211-266). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Pelled, L. (1996). Demographic diversity, conflict, and work group outcomes: an intervening process theory. Organization Science, 7(6), 615-631. [ Links ]

Perreti, F. & Negro, G. (2007). Mixing genres and matching people: a study in innovation and team composition in Hollywood. [ Links ]

Triguero-Sánchez, R., Peña-Vinces, J.C., & Sánchez-Apellániz, M. (2011). HRM in Spain its diversity and the role of organizational culture: an empirical study. European Journal of Social Sciences, 26(3), 389-407. [ Links ]

Triguero-Sánchez, R., Peña-Vinces, J.C., González-Rendón, M., & Sánchez-Apellániz, M. (2012). Human Resource Management Practices aimed to seek the commitment of employees on the financial and non-financial (subjective) performance in Spanish Firms: An empirical contribution. Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative, 17(32), 17-30. [ Links ]

Van Knippenberg, D., & Schippers, M.C. (2007). Work group diversity. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 515-541. [ Links ]

Walton, R. (1985). From control to commitment in the workplace. Harvard Business Review, 63(2), 77-84. [ Links ]

Williams, K.Y. & O'Reilly III, C.A. (1998). Demography and diversity in organizations: A review of 40 years of research. In B. Staw & R. Sutton (eds.) Research in Organizational Behavior, 20, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press 1998, 77-140. [ Links ]

Woehr, D.J., Arciniega, L.M., & Poling, T.L. (2013). Exploring the effects of value diversity on team effectiveness. Journal of Business Psychology, 28, 197-121. [ Links ]

Wright, P.M., & Nishii, L.H. (2006). Strategic HRM and organizational behaviour: integrating multiple levels of analysis, CAHRS Working paper series, 05, http://ilr.corneli.edu/CAHRS. [ Links ]

Article history:

Submitted: 20.06.2015

Received in revised form: 18.12.2015

Accepted: 19.12.2015